Search Results for: F word

Genre: Sorta Horror/Teen

Premise: A high school begins to fall apart when its students start spontaneously combusting.

About: This project is based on a recent novel written by Aaron Starmer. It will star Katherine Langford from 13 Reasons Why. Brian Duffield not only adapted the screenplay but is also making his directorial debut. The movie was shot in January of last year so I’m not sure why it hasn’t come out yet. Spontaneous is one of the first films to come from AwesomenessTV, which is one of the biggest channels on Youtube.

Writer: Brian Duffield (based on the novel by Aaron Starmer

Details: 110 pages (First Draft)

I like going into Brian Duffield scripts as naked as possible. Not physically of course. But I don’t want to know anything. One of the great things about Duffield scripts is that crazy things can happen at any moment and I don’t want to spoil them before they happen.

With that said, I heard through the grape vine that this was an adaptation, and that definitely colored my reading experience. Duffield has worked almost exclusively on original material, which has been great because his mind doesn’t work like anyone else’s. So if he’s working off of someone else’s idea, he has to reign in some of that famous creativity.

And as we’re about to find out, that’s not the best way for him to work.

Spontaneous is Thirteen Reasons Why meets John Hughes meets Warm Bodies. 17 year old Mara is sitting in Pre-Calc when the girl in front of her, Katelyn, explodes. At first, everybody assumes it’s a school shooting so they run around the hallways like chickens with their heads cut off. But eventually they learn that Katelyn wasn’t shot. She spontaneously combusted. Or exploded.

While Mara and her best friend, Tess, struggle to make sense of what happened, fellow senior and kinda weirdo, Dylan, crashes the party to say hi. Dylan, it turns out, has been in love with Mara from afar all throughout high school. Lucky for Dylan, Mara’s kind of liked him, too. So the two start dating. Which should be a happy time. Until another senior, a gay football player, spontaneously explodes.

Now it’s an epidemic. Which means the media and the authorities descend on this small town, E.T.’ing it so no one can come in or out. They start doing all these experiments on the kids, until they eventually develop a pill that keeps people from spontaneously exploding. And so it’s BACK TO SCHOOL for everyone, where it seems like everything is normal again. That is until a mass of spontaneous explosions occur (spoiler) including Dylan!

With the love of her life gone, Mara suspects that she’s the curse that killed everyone. I mean, Katelyn was right in front of her when she exploded. Dylan was around her all the time and he exploded. So it must be true. But eventually Mara philosophizes that life sucks no matter what and that all you can do is your best before you die. The end.

Hmmm…

I don’t know who to direct my disappointment towards here. While Duffield wrote the script, everything is based on the book. And, as the saying goes, you’re only as good as your source material.

Look, the good news is that this is an original premise. No zombies. No vampires. No aliens. No monsters. The spontaneous combustion premise is unique.

The problem is, the author didn’t know what to do with that premise. For starters, it’s a terrible premise for building tension. At least when you have zombies, you can create suspenseful situations as those zombies slowly move in on our trapped characters. But with spontaneous combustion, it’s random. There’s no way to build tension with randomness. You’re sitting around for 25 pages of dialogue and then you hear how a new person just blew up. I’m not sure there’s any way to fix that problem.

Nor is the structure here story-friendly. It’s a car ride where nobody tells us where the destination is. So we’re not even the annoying kids in the back screaming, “Are we there yet?” We’re the annoying adults screaming, “Where are we going?”

Theoretically, this sets the stage for what Duffield does best. He can plant two characters in a room and let them dialogue away. Indeed, the dialogue here feels effortless and flowing. The problem is, because there’s no plot, and therefore nobody’s trying to get anywhere in these scenes, they start to get tiring. And repetitive.

And this is why it’s so important to figure out your structure ahead of time. Because if you repeatedly drop characters into scenes where they don’t want anything other than to talk to each other, the story’s never going to feel like it’s advancing.

When you’re writing a story like this, you have two directions you can go in. Direction 1 is to create a mystery behind the problem (spontaneous combustions) that the characters are trying to solve. This gives your heroes a goal and therefore a purposeful journey. “Why are people exploding,” Mara can say. “Let’s investigate.” They don’t do that here. Scientists come in and try to figure things out. But our heroes spend that time sitting around waiting. The other option is to use your story as a metaphor for something. At least that way, we get the feeling that there was a purpose to the experience. If this teaches us a powerful lesson about life, it can work.

But this didn’t do that either (or, at least, this draft didn’t). And I think it’s a source material problem because I went to Amazon afterwards and I was seeing the same complaints in the reviews. The author had his characters talk the whole time while a bunch of people blew up without explanation and in the end, capped it off with, “that’s the randomness of life.” I think I speak for writers everywhere when I say that if your theme is, “randomness of life, bro,” you probably haven’t dug deep enough.

I’ll say it again: you’re only as good as your source material. You’re never going to teach Danny DeVito to be Roger Federer. Then again, it’s important to note that this is a first draft, that Duffield likely added more structure in the subsequent drafts. But for this to have worked, somebody would’ve needed to come up with a radical idea on how to make this concept movie-friendly. I hope that’s what Duffield did. Cause if this movie does well, he’ll get to make some of his own scripts. And that’s what I’d really like to see.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It’s dangerous to give characters other than your heroes the active storyline. In other words, the goal here is to find out why these spontaneous combustions are happening. But that goal is given to the FBI and scientists while our heroes sit around and wait for them to finish. You want your heroes to be involved in the ultimate goal of the screenplay. 99 times out of 100, that results in a better script.

Heads up! Going to share some good news tomorrow about Jason Gruich, who wrote “Cop Cam.” Let’s keep the good vibes going. Submit your script for this weekend’s Amateur Showdown Contest! You can find the submission rules here. See you soon!

One of the best ways to learn dialogue is through comparison shopping. You compare similar scenes between bad dialogue and good dialogue. Or you take a great scene of dialogue you remember from a movie and, without rewatching it, write your version of the scene, then go back and compare the two. Trust me, you’ll learn a thing or two about how to write good dialogue.

The show with the best dialogue going right now is, without question, Succession. Succession follows a Rupert-Murdoch-Slash-Robert-Iger type, named Logan Roy, who has a stroke, forcing his incompetent family to take the reins of the business. The show manages to perfectly balance a serious tone with offbeat humor. And that’s your first dialogue lesson for the day. Most of what we think of as “good dialogue” has a humorous component to it.

So here’s what we’re going to do. You’re going to write your own version of today’s featured scene before you read it. You’re then going to compare it to the real scene. It doesn’t matter that you haven’t seen the show. I’m going to give you some background on the scene in a second. For those of you brave enough, post your scene in the comments. Let’s see if anyone can top the dialogue from the show. I doubt it will happen. The dialogue here is really good. But if you get a ton of upvotes, I’ll concede.

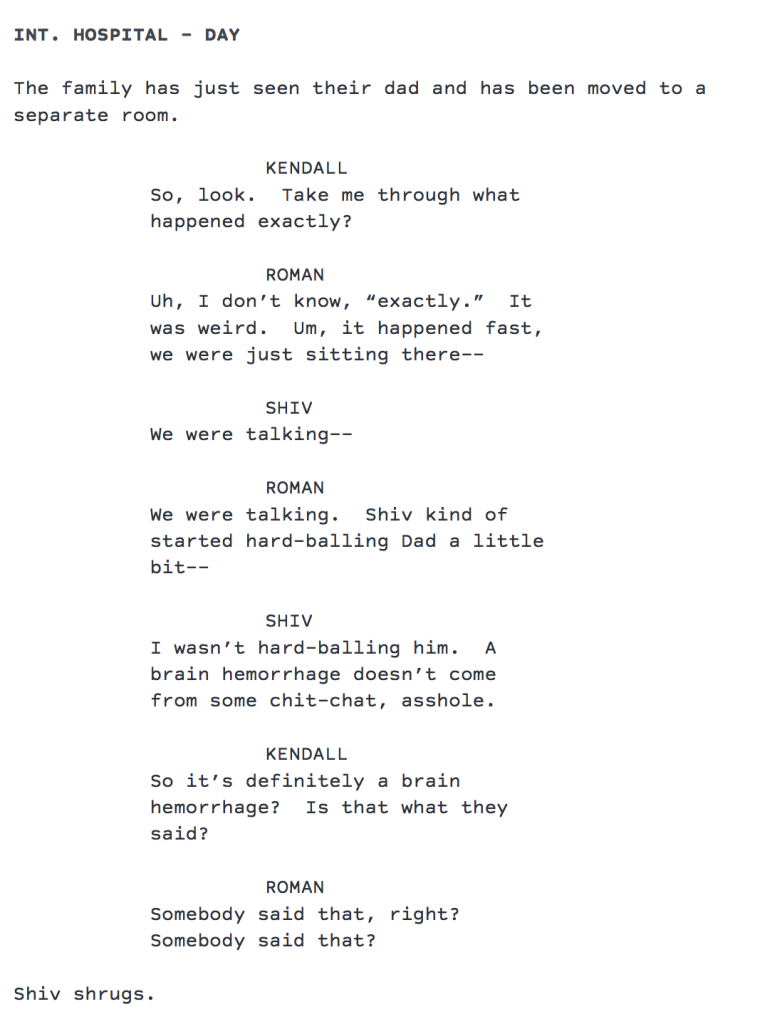

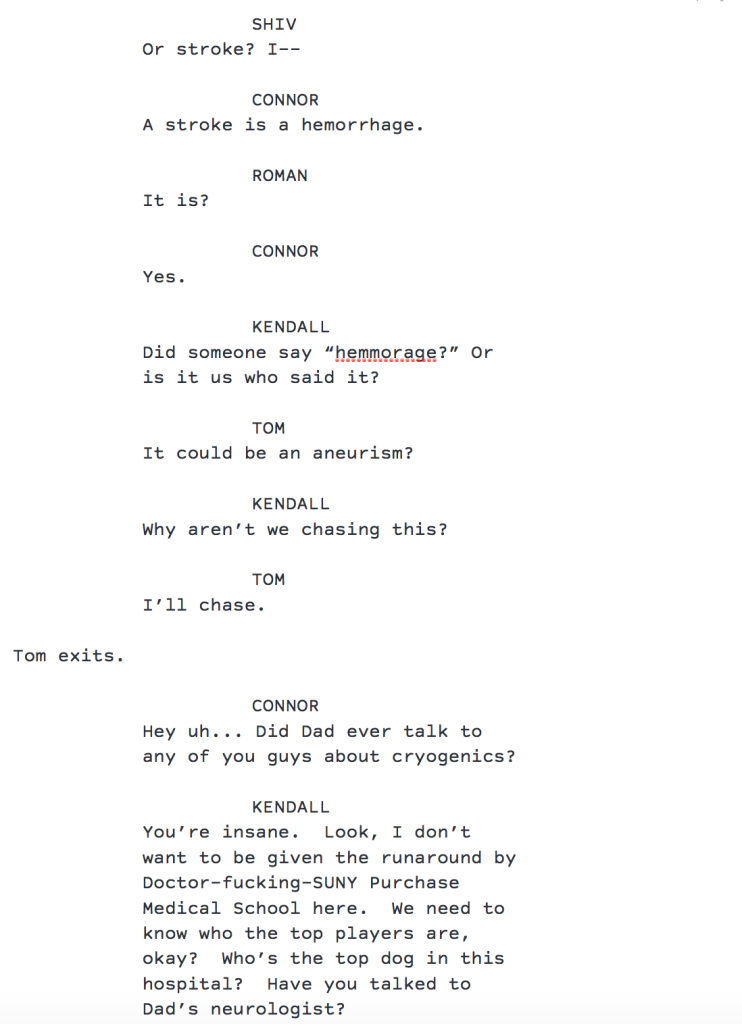

The scene in question occurs after Shiv (Logan’s daughter) and Roman (Logan’s youngest son) are flying with their dad in a helicopter. During their conversation, the dad has some kind of head rush and passes out. They rush him to the hospital and have a quick talk with an Indian doctor before they’re reassigned to a new room with the rest of the family. They don’t have an official diagnosis yet but they think it may be a brain hemorrhage. The point of the scene is for the family to find out what just happened and then decide what to do next.

The five characters in the scene:

Kendall Roy – 30s, a Donald Trump Jr. type. Talks a big game but is insecure. He’s the leading contender to take over the company but the rest of the family has zero confidence in him.

Roman Roy – late 20s, Kendall’s eccentric younger brother who hates work and just wants to screw around and have fun. Very much a “dialogue-friendly” character.

Shiv Roy – 30s, the sister. The most level-headed of everyone. The only one here who’s more concerned about dad’s health than the company.

Connor Roy – Oldest son from a previous marriage of Logan’s. A bit of a weirdo who goes off on tangents.

Tom – Shiv’s fiance. We’re not sure if this guy loves Shiv or loves that he’s found a way into the Roy family. The family is a little hesitant about him.

I couldn’t find the script for this show, so I’m transcribing the dialogue myself. I’ll only refer to action when it’s necessary. But the description here is not the writer’s. It’s mine. Okay, let’s get to it!

Now if you have an acute dialogue eye, you’ll notice something off about this dialogue. IT SUCKS. That’s right. It sucks. I call this “Basic B@%$# Dialogue.” It’s dialogue anybody could write. You could literally pluck a tourist off the streets of LA and teach him to write this dialogue in ten minutes. I wrote this dialogue. To teach you a lesson. That dialogue can be so much more than you make it. Wanna see the actual dialogue? Okay, here it is.

Same situation. Same things are accomplished. Why is the dialogue in the second version so much better? For starters, note that we’re playing against the obvious emotion here. This is a sad scary situation, yet we’re still injecting humor into it. There’s something else going on here that you see throughout the show and I brought it up during the last dialogue article. There’s a sense of playfulness in the writing, a desire to take chances and go outside the strict confines of a nuts and bolts conversation. If you want to write better dialogue, be more playful. Have more fun.

Now let’s look at some specific moments. Notice Roman’s response to Kendall’s initial question. “Uh, I don’t know, ‘exactly.’ It was weird. Um, it happened fast, we were just sitting there—“ “We were talking—“ “We were talking. Shiv kind of started hard-balling Dad a little bit—“ To be honest, I don’t know if the “ums” and “uhs” were written or if they were an acting choice. But I’m going to assume they were written. Normally, writers would be afraid to write a response like this. There’s something “unclean” about it. One “um,” maybe. But two? In one response. They would be scared of that. And yet it’s what helps the dialogue feel so natural.

In addition to that, notice how the character isn’t allowed to finish before another character butts in. Interruption is ANOTHER thing that helps make dialogue feel natural. So doubling up on these “naturalistic” flourishes is already selling the dialogue way better than the Basic B@%$# version.

Notice also that when someone asks a question, the answer is not a robotic 1 or 0. It isn’t “This” or “That” happened. Roman takes the answer off on an aside. “Shiv kind of started hard-balling Dad a little—“ Already, we’re drifting away from the straight-forward on-the-nose dialogue in Basic B@%$#. Not only that, it gets Shiv to defend herself, which further derails us from getting the answers. This is the trick to dialogue. You don’t want it to be a straight-forward exchange of information. You want it to be messy, like real life! And that’s what the writer was doing here.

What really brings the scene up a notch, though, is Connor randomly bringing up cryogenics. First off, this dialogue is born out of character. It’s not just a writer trying to be funny. This is who Connor is. He’s a weirdo who’s an outcast of the family. He always says stupid stuff like this. This keeps his tangent grounded. If Shiv had said this, it wouldn’t have worked. It works because it’s born out of character. And now we’ve gone even further away from getting the answers we need. Which is what you want to do with dialogue. You don’t want it to be easy. You don’t want everybody to agree and read each other’s minds with perfect responses. You want it to be difficult. Because that’s how conflict is created and what keeps the dialogue fresh and fun.

So what about you? What differences did you notice between the Basic B@%$# version and the real version? What differences did you notice between the real version and your own version? Compare compare compare. The more you compare your dialogue to the best dialogue in the industry, the better you’re going to get at it. Now let’s see how your own scenes turned out.

Yo, do you have a logline that isn’t working? Are those queries going out unanswered? Try out my logline service. It’s 25 bucks for a 1-10 rating, 150 word analysis, and a logline rewrite. I also have a deluxe service for 40 dollars that allows for unlimited e-mails back and forth where we tweak the logline until you’re satisfied. I consult on everything screenwriting related (first page, first ten pages, first act, outlines, and of course, full scripts). So if you’re interested in getting some quality feedback, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: “CONSULTATION” and I’ll get back to you right away!

Genre: Vampire

Premise: After the United States survives a vampire war, a young human girl going through puberty learns that she may be turning into a vampire.

About: Bill Kennedy is best known for writing a number of episodes for House of Cards. With this spec, he got onto last year’s Black List, garnering a respectable 10 votes.

Writer: Bill Kennedy

Details: 95 pages

One of the tricks that savvy screenwriters use to gain traction in this industry is to take a big idea and execute in a small way. The way it works is that you get the conceptual residue of the big idea, but you do it in an affordable manner. The backstory for this script revolves around a giant war with vampires. Yet we never see that war. We’re just living in a small town 25 years after it’s ended.

If you do it right, the reader is imagining this big expansive world all by themselves. You don’t have to show any of it. And because there are no big production expenses, the number of potential buyers for your screenplay skyrockets. This is similar to what they did with the movie Maggie. Although I would argue that Kennedy does it better in Just a Girl.

In addition to introducing this trick, Kennedy incorporates another time-tested narrative, which is to use a flashy gimmick as a metaphor for puberty/adolescence. In this script, our 16 year old hero is turning into a vampire. But what she’s really turning into is an adult. You savvy Scriptshadow readers probably remember a few similar scripts I’ve reviewed here. In one of them, a 16 year old girl is turning into an insect. And, in another, one is turning into a superhero.

The great thing about these two “tricks” is that not many writers know about them. So you can use them and, assuming you execute them well, look like a genius. So how did Just A Girl turn out? Let me down this Big Gulp cup full of blood first and I’ll tell you.

We meet 16 year old Samantha in her small town during a parade. But this parade’s a little different from the ones you’ve been to. It’s celebrating the anniversary of the end of the Human-Vampire war. 25 years ago, humanity finally figured out how to defeat the vampires, and since then, the planet has been a vampire free zone.

Samantha’s best friend is Annabeth. The two are somewhat outsiders at high school. They’re pining over the popular boys who already have their popular girlfriends. But the cool kids start taking a liking to Annabeth, who eventually pulls away from Samatha to join the popular clique.

Samantha is devastated by the loss of her best friend, but it turns out she’s got bigger fish to fry. She’s starting to crave blood for some reason. Finally, one day, she can’t take it anymore, so she kills a squirrel and drinks its blood. The experience is euphoric so it isn’t long before she’s killing bigger animals. Meanwhile, she’s getting stronger, and more importantly, stops giving a sh*&.

This “whatever” attitude ironically gets the boys’ attention. And Samantha isn’t shy about letting those boys know she wants to lose her virginity. Soon, her and Annabeth are hanging out again and it isn’t long before Samatha is pressuring Annabeth to do naughtier things. Let’s get drunk. Let’s go to parties. Let’s have sex with boys. There’s a recklessness to Samantha. She needs constant chaos.

Unfortunately, Samantha’s parents become suspicious and when she least suspects it, the cops show up and take her to the hospital for tests. They find out she’s a vampire, which is impossible. There hasn’t been a vampire on earth for over two decades. It’s clear what they have to do but Samantha is able to escape before they do it. She finds Annabeth and prepares to make a run for it. Will they make it into the wilderness in time? Or will they both be hunted down and killed?

This was quite good. Not only is the premise clever. But the execution is sound.

And this is where most new writers falter. They’ll come up with a premise like this and not have a plan for what to do next. They’ll have 4-5 scenes in mind. They know Samantha’s going to be at school a lot and get into some dustups with the popular girls. They know she’s going to have sex at some point. But that takes up 30 pages of the script. What’s the rest of the story? You could argue that this is the crux of the screenwriting struggle. Who can only fill up 30 pages of material and who can fill up 90. I know a lot of people who can fill up 30. Very few who can give us another 60.

So what’s the trick to it? Besides the basics, one of the tricks is escalation. And what escalation is, is that every 12-15 pages, the story needs to make a jump. Let’s say you write a version of this movie where Samantha and Annabeth go to school and deal with the typical issues that teenage girls deal with. Okay. Go ahead and do that for 15 pages. But then you have to escalate. You have to give us something new that makes these next 15 pages feel a little bigger and a little different from the previous 15.

So Bill has Samantha being shy and introverted at first. And then 15 pages later, she starts killing and drinking animal blood, resulting in a bolder more reckless Samantha. And then 15 pages later, she’s gone full-goth and needs to have sex at all costs. And then 15 pages later, she’s getting in a fight with the entire LaCrosse team, using her vampire strength to beat all of them down. In other words, the story keep escalating. Each 15 pages feels bigger than the last.

And to some of you, this might sound obvious. But I can promise you, based on all the amateur scripts I read, it is anything but obvious. For some new writers, it’s just that they don’t know that the story has to keep advancing. But the bigger fault lies with writers who DO know this rule, and yet they love their writing so much that they feel they’re exempt it. They see this as a “gimmick” that their script is somehow above. They believe that they can write 45 pages of Samantha and Annabeth chilling out at school with no major plot advances. But the reality is, you’re boring us. You need to keep your story going. You need to keep escalating it to the next level. Especially a story like this that’s stationary. It’s so easy to fall into the trap of writing a passive story when your characters aren’t physically moving anywhere.

Ironically, that leads to the script’s one fault, which its ending. In the desire to keep upping the stakes, the ending of this script becomes… I don’t want to say like a superhero film. But, tonally, it felt like the wrong ending. Going on the run and having police chase you doesn’t quite work. We needed to finish this in the town. But to be clear. Escalating the stakes to make the climax bigger than the rest of the script was the right move. I just didn’t like the creative choice of going on the run and making it Dark Phoenix 2.

Still, I’m very happy that I reviewed this script. It’s yet another in a string of scripts I’ve reviewed these past two weeks which are all great examples of spec scripts you should be writing. From Don’t Worry Darling to Pyros to Cop Cam and now Just A Girl. Each of them have components that make them spec sale friendly. Check this script out if you get a chance.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’ve ever received the note that your script is “repetitive” or that “not much happens?” these are indicators that you don’t escalate your script every 12-15 pages. After 12-15 pages of story, try to imagine that there’s a ladder that you have to climb your script up to get to the next level. Cause if it stays down here on the street it’s been on for the last 15 minutes? Chances are people are getting bored.

I want you to imagine a scenario with me. You’ve just become the hot cool screenwriting thang on the block. Your nifty biopic about the woman who invented the trampoline finished with 27 votes on the Black List. All of a sudden everyone wants to meet with you. So you go to meeting after meeting and it’s all smiles and high-fives and then, at your final lunch with an executive at at Paramount Pictures, you learn that Michael Bay liked your script so much, he wants you to write the new Transformers spin-off! He feels like your inherent understanding of life’s complexities are going to work great for an Optimus Prime origin story.

So you go off and you write what you feel is a really good Transformers movie about how working in the trucking industry for 20 years helped him become the great autobot leader he is today. You’re not patting yourself on the back or anything. But if they film this script as is? It will be the best Transformers movie by far. There’s more depth and nuance in the final 10 minutes than there have been in all the Transformers movies combined. You’ve heard nightmare stories about getting bad notes from clueless executives, so you’re ready. This is your big shot and you’re going to look at everything through a positive lens.

Well, the primary executive you’re working with on the project, Colin, tells you that he really likes your script, but he’s been mulling it over and wants to go in a different, more exciting, direction. He wants Optimus Prime to be a dinobot. You see, Jurassic World 3 just came out and did bonkers box office and it would be a lot easier to sell this movie with a dinosaur as the protagonist. Uhhh… but this means erasing the truck delivery storyline, which is a key part of Optimus’s transformation. You’d basically have to scrap the whole script and start over. Don’t worry, Colin tells you. You’re a good writer. You’ll figure it out.

So you go and you write a new script, this one starting in the dinosaur age, where Optimus, now a dinobot, has to hide out from the Decepticons. You add a great climactic set piece where Optimus barely escapes death by meteor. You send this new draft in and Michael Bay wants to meet with you. He’s been busy filming a movie so this is the first draft he’s read. “Why is Optimus a dinosaur?” he asks. This movie is about a truck. It’s about truck-driving. You try and explain what happened but all Michael can say is, “Let’s go back to the truck story. Except I had a new idea. We’re going to set this in the future. Way in the future. We’ve seen present-day Transformers too many times. We’re going to give them something different this time around…”

One of the complaints that always bugs me about writers is when they moan and groan about the different writing standards for amateurs and pros. They see a hackneyed sloppily written stinker like Hobbs and Shaw, a movie that’s being played in over 4000 theaters in America alone, and they say, “This script is terrible. Nothing makes sense. Yet my script is dismissed because I had a spelling mistake on page 2.”

Let me say this. I understand every aspiring screenwriter’s frustration. I don’t know if there’s a more inherently demoralizing pursuit than writing. You spend six months writing a screenplay or two years writing a novel, and after you finally finish, a bunch of people tell you, “Meh. It was okay, I guess.” You’ve got to be quite the masochist to put yourself through that experience time and time again. So from the bottom of my heart, I understand your pain.

But now let’s remove feelings from the equation, since nobody in Hollywood cares about your feelings. And let’s look at this objectively. When screenwriters are called upon to write a movie for a studio or a production company, they are no longer the author. The person who’s bankrolling the movie is the author (or whoever the bankroller anoints as the project head). Therefore, you’re not so much writing as you are solving problems. People are coming to you, just like my Transformers example, and they’re telling you to change what you believe are good ideas into bad ones. They’re telling you that an actor wants their character to have more jokes even though that character isn’t a joker. They’re telling you they can’t afford to shoot at Times Square, so you’ll have to move the scene to a forest, even though that fundamentally changes everything about the movie. And these are just normal problems. Wait until you run into a director who decides to rewrite the script you just spent four years on two weeks prior to production.

When that movie then comes out and it doesn’t make sense at all… you blame that all on the screenwriter? The screenwriter is usually the person with the least amount of say on a project. All they can do is pick their battles and try to keep some semblance of a good story together.

Now some of you might say, “Well The Departed was a great script,” or “Schindler’s List rocked.” “So obviously IT IS possible for good movies to be made.” Well yeah. Of course. There are people in Hollywood in powerful positions that understand story. And when those people are shepherding a project, they’re going to be successful more often than not. But, unfortunately, most projects have people working on them who don’t know storytelling well. They may know marketing well. They may know character well. But they don’t know how to put together an A to Z story so they force a lot of bad ideas that you have to incorporate into your script. Does that make you a bad writer? No. Of course not.

Maybe the most high-profile example of this is Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. It is one of the worst screenplays you’ve ever seen make it to the big screen. Long time A-list screenwriter David Koepp wrote that screenplay. Now do you think that David Koepp had any input on that screenplay whatsoever? David Koepp was a glorified exposition typist. They gave him a bunch of set pieces and story beats that didn’t fit together then asked him to make it make sense. This is why it’s so confusing for outsiders to process this. They see David Koepp’s name on this awful movie and they think, “Why would they keep hiring him? That film was trash.” Yeah but everyone knows Koepp had little to no say on how that screenplay went.

Now let’s turn to you, the amateur screenwriter. Your audience is completely different than the professional screenwriter. Let’s start there. The professional is more or less transcribing what someone else wants. That someone is the only audience they have to please. You, on the other hand, are writing to a very specific audience – and I want you to internalize this because it’s probably the most important point I’ll make all post – your audience is people tasked with reading terrible scripts over and over and over again. They have read so many bad screenplays, that by the time they read your script? They are both exhausted and assuming it will be just as bad as everything else they’ve read. Not because they’re trying to keep you down. Because that’s been the reality of their job. So, obviously, you’re going to need to come up with something pretty great to win them over.

There’s a second challenge to this. And I can speak about this from experience. Nobody is interested in you passing them a script that’s pretty good. In every instance where I’ve passed something up to someone – an agent or a producer – that I thought was pretty good, I was basically told to stop wasting their time. The only time anyone wants you to pass something to them is if it’s awesome. And even then, they usually read it and say “no thanks.” The reason why this is important to understand is that a lot of times, a reader will read something that’s genuinely decent. It’s got problems but they weren’t bored while reading the script. Unfortunately, these readers know that even though they thought the script was good, their boss or whoever had them read it, won’t care. They’re only going to care if you’re over-the-moon about the script.

This is a big reason the standards between amateurs and pros are different. You’re writing under a completely different set of circumstances than the pro writer. Now of course, there are other scenarios besides the “studio assignment.” A writer who just had a big sale comes out with another spec and it’s not very good. Well, a producer only cares about getting movies made. And if they have a spec from one of the hottest writers in town, that’s worth something, even if the script isn’t very good. “Us” wasn’t a very good screenplay. It was kind of all over the place. But is there any studio in town who wouldn’t have made Jordan Peele’s second movie? Of course not. So you have to factor that in.

How do you write one of these scripts that blows people away? Or wins a screenplay contest? There is no magical formula. But I can tell you this. Make sure you’ve got a professional presentation. Don’t let the reason you lose a reader be laziness. All of the “basics” need to be on lockdown. From there, it’s about picking a great concept – you can improve your chances of this by sending your ideas to friends and asking them to honestly rank your idea from 1-10. And then executing the story in a way that continually keeps the narrative exciting. We should always WANT to turn the page. We should never feel like we HAVE to turn the page. The more you study screenwriting, the more scripts you write, and the more scripts you read, the better you’ll get at that last part. And to all of you I say, I hope you eventually write the greatest script ever. Because it’s so much easier to read a good script than a bad one.

Yo, do you have a logline that isn’t working? Are those queries going out unanswered? Try out my logline service. It’s 25 bucks for a 1-10 rating, 150 word analysis, and a logline rewrite. I also have a deluxe service for 40 dollars that allows for unlimited e-mails back and forth where we tweak the logline until you’re satisfied. I consult on everything screenwriting related (first page, first ten pages, first act, outlines, and of course, full scripts). So if you’re interested in getting some quality feedback, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: “CONSULTATION” and I’ll get back to you right away!

Genre: Sci-Fi (short story)

Premise: In the near future, “Tardy Men” – a new breed of firefighter with high-tech fire suits fused into their spines – go into dangerous fires to retrieve valuable items for the rich.

About: This package is still coming together and, along with hot spec sale, Don’t Worry Darling, last week, is drawing major bids from multiple studios. It looks like Simon Kinberg, who will direct, discovered the short story, which appeared in The New Yorker, and changed the main character from a male to a female so that Reese Witherspoon could play the lead. A cool footnote is that the author of the short story, Thomas Pierce, will be writing the screenplay. The film will be retitled, “Pyros.”

Writer: Thomas Pierce

Details: short story – 1200 words

I never cared about Simon Kinberg being a big successful Hollywood writer/producer despite a body of work that suggested below-average talent UNTIL he joined the Star Wars team. Cause I love Star Wars. I wanted great Star Wars movies. And then, out of nowhere, I’ve got the guy who’s making some of the worst superhero movies in history involved in Star Wars in a major capacity. That’s when I began the anti-Simon Kinberg movement.

When this project hit the airwaves, my interest was piqued because it’s such an odd move for everyone involved. You’re going to have a studio committing major dough to a 1200 word short story. You’ve got Reese Witherspoon taking on her first ever hard sci-fi role. And you’ve got Kinberg trying his hand at original material, as opposed to the safety net of well-known IP. On top of that, it’s an admittedly intriguing premise in that it’s a sci-fi idea I’ve never seen before. That’s hard to do in any genre, but especially sci-fi.

Also, these are always good reminders for writers about what kind of stuff Hollywood is searching for. We spend so much time in our delusion bubbles convincing ourselves that any idea we come up with is genius, we forget to look at real-world “this is what sells” data.

Let’s take a look.

Tardy Man begins with a man talking to us using abbreviated language. “Can’t talk thru suit. That’s why note cards,” he tells us. He then proceeds to explain that he’s a “Tardy Man,” as in “fire retardant.” His “Tardy Suit,” he explains, is connected to his spine and he can’t remove it without help “or else death.” That’s why he has to “use note cards.”

He explains that his job is to run into big fires, the kind that take up entire neighborhoods, and recover things for rich people. The company he works for, Wick, has one rule. The item they paid you to get is the only thing that matters. Doesn’t matter if you see a dying dog. Doesn’t matter if a person is stuck under a dresser on the second floor. You get the item and that’s it.

In today’s case, he needed to obtain a bin that kept important items for a rich family. While he was walking to the house, he saw a little kid in the pool. Only place for him to stay safe. He walked by the kid but later goes back to get him, even though Wick has been known to kill Tardy Men who disobey the rule.

He then places the boy in the bin and goes on a long trek through the fire-fueled forest, to the safety of a random home just outside the fire. That’s when we realize this is the woman he’s been telling the story to the whole time, the woman he’s asking to take the boy. Now he has to get back to Wick and hope they don’t find out what he did. The End.

Well, I may not be the biggest Simon Kinberg fan, but in this case, he nailed it. This was really good.

For starters, it’s cleverly written. I love the mood the abbreviated style creates and I love that the abbreviation is motivated. Not only that, but it’s used as a semi-mystery to drive the story. Why is this person talking like this, we’re wondering.

But here’s the real reason I liked this story.

One of the most pivotal moments in this business is when you pitch someone an idea. In that moment you’re either going to get a yes or a no. And the significance of this is that it will be added to the total tally of yeses and nos, which provide you with a pretty clear picture of whether your idea is good or not.

However, what a lot of writers forget is that there’s a secondary pivotal moment within the pitch itself. It’s the moment when you give the person the definitive image that proves your idea is worthy of being a movie. In Blake Snyder’s book, Save the Cat, he talks about this moment with his big spec sale, Don’t Stop Or My Mom Will Shoot. During the pitch, there was a moment where he described a car chase where his protagonist was forced to be a passenger in his mom’s car during the chase, leading to the slowest car chase ever. It was that moment that the producer said, “This is a movie.”

That’s the goal of the definitive image. It’s your highlight image that sells the movie. Another example would be the birth scene in A Quiet Place. Establish that monsters kill you if you make any noise and then force one of your characters to give birth within that construct. People hear that and they go, yup, that’s a movie. No question about it. A more specific way to look at this is, “What’s going to be the moment in the trailer that makes people want to see this movie?”

That moment occurred while I was reading this short. Early on, the Tardy Man was walking through the backyard of this house he had to go into, and he sees this desperate child in the pool. And he just… keeps walking. That’s it right there. That’s the movie. You show a man in a giant deadly fire who sees a boy who needs saving and he just walks right past him? That shocking image is going to sell the movie. And, actually, it’s going to sell it even better when Reese Witherspoon is doing it. Because women are supposed to be motherly. And for her to coldly walk past a boy who needs help… that’s going to get literally “ohhhhs” from the audience.

There was another line I really liked here as well: “Very, very sad situation. Tardy Man a good person. Too good. Wick doesn’t like good ppl.” This implies that “Tardy Men” need to be cold and unfeeling. They must learn to eliminate their emotions. They’re here to do a job and the job is all that matters. That’s a really interesting character for actors to explore, and I’m going to assume it’s the reason Reese signed on.

It’ll be interesting to see if Kinberg uses the entire story here as the basis for his screenplay or if he only uses the core concept. Because while transporting a boy in this box that supposedly only has an hour of air in it gives the movie a nice ticking time bomb, something tells me there’s so much more you can do with this idea. You could create an entire mythology behind the house and the people who own it and what they want the Tardy Man to retrieve and maybe it’s something illegal. I like the idea of him having to save someone, but I don’t think it should be a real time 90 minute “walk through a fire” story. I’m afraid that might get boring.

This is easily one of the best short stories I’ve read. It’s so hard to come up with a good story in a thousand words, but somehow this Thomas Pierce guy pulled it off. I’m really looking forward to this now.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This was a wake-up call to me that not every low-to-mid budget sci-fi idea has to be some dumb time-travel thing or “people stuck in a ship” or “wake up in a strange room” idea. Not that you can’t write good versions of those movies. But of the hundreds of low-budget sci-fi scripts that I’ve read, 90% of them are those three setups. Expand your imagination and look for sci-fi ideas in unexpected places.