Search Results for: F word

Genre: Time Loop

Premise: A retired U.S. Army Special Forces veteran finds himself stuck inside the same day where a group of assassins hunt him down and kill him.

About: This script was originally written by Chris and Eddie Borey, who have a knack for high-concept ideas. Their last film, Open Grave, was about a man who “wakes up in the wilderness, in a pit full of dead bodies, with no memory and must determine if the murderer is one of the strangers who rescued him, or if he himself is the killer.” Writer-director Joe Carnahan got his paws on the script and decided to make it. But as one of the best writing directors our there, he gave it the Carnahan rewrite special. The film will star Mel Gibson, Ken Jeong, Frank Grillo, and Naomi Watts.

Writer: Joe Carnahan (original script by Chris and Eddie Borey)

Details: 118 pages

It’s official. Time Loop is a genre.

I still don’t know how this happened but I’m not mad. So far, the format has withstood all the excess use. The most recent time-loop project, Netflix’s Russian Doll, was nominated for an Emmy.

The rules for getting these movies right are the same as they are with any genre. You must answer the question, “What new are you bringing to the table?”

Former Special Forces soldier Roy calmly explains to us in voice over why it’s so easy to kill this trained assassin who’s woken him and his one-night stand up by trying to stab Roy in his face. Ya see, Roy explains, he keeps waking up on the same day – today – with this man trying to kill him. And when he kills this man and the Matrix-like helicopter with the Gatling gun that follows, he runs outside where a woman named Pam starts shooting at him from a car.

He must carjack a car from a man who always screams, “He’s carjacking me!” and if he’s able to outrun Pam, he runs into a sword-smith, Guan-Yin. If he can somehow defeat her, he goes to a local bar and drinks. That’s because no matter what Roy does or where he goes, assassins never stop coming after him until he’s dead. He’s never even reached noon. This is the one place where he has about an hour before they find and kill him. Then his day starts all over again.

How did we get here? We get some insight into that when we jump to yesterday and meet Jia, Roy’s ex-wife and the mother of his son. Jia is a scientist who works at an experimental company called Dynow. Jia is working on a doomsday device for her scary boss, Colonel Clive Ventor. Ventor is getting angry that he’s poured all this money into this project and the device STILL isn’t working. He tells Jia that if she doesn’t figure it out fast, there will be consequences.

Roy knows nothing about all that. In fact, Jia is killed by Ventor before loop day so he can’t call her and ask what’s going on. One morning he decides to look into an old theory – that they’ve hidden a tracking device on him. But he’s never been able to find it. So he goes to a friend who knows about this stuff and asks him where he’d put a tracking device if he wanted to track someone. The guy says, “in your teeth.” Roy says, “Can you check my teeth for me?” “No,” his friend says. “I’d need to see each tooth separately.” So Roy grabs a pair of pliers and proceeds to rip each of his teeth out one by one until they finally find out that, yes, one of his teeth has a tracking device in it.

Armed with this info, Roy can get rid of the tracking device every morning, and now has the drop on all his assassins. He can simply plant the tooth, wait for them to show up, and kill them from behind. But Roy needs to do more than that if he’s ever going to escape this time loop. So he infiltrates Dynow, convinced they’re somehow responsible, where he discovers the doomsday device. Armed only with a secret message Jia told him “yesterday,” he must destroy the device and restore time to its rightful state.

I love me some Joe Carnahan. His scripts almost make me uncomfortable with how confidently they’re written. The guy is the screenwriting equivalent of an alpha gorilla. He plows through the page and all we can do is hold onto the edge and hope we don’t fall off.

Boss Level is a natural fit for him. This is a guy who loves tough colorful characters who shoot big, fight bigger, and talk biggest. He gets to do all of that here but inside a time loop scenario. This adds a level of sophistication to the story that Carnahan sometimes seems uninterested in. Boss Level keeps you thinking while you’re enjoying all the action making the script work like one of those dual level bridges.

Like every writer should, Carnahan deviates from the time-loop formula to add a new layer to the story. Right after the first act, Carnahan cuts to “yesterday.” This allows us to meet Roy and Jia before all of this went down, as well as get some context on what Jia did and how her company is connected to all this.

Without this foray, the script would’ve gotten repetitive, one of the biggest pitfalls in the time-loop genre. Once we jump back into Roy’s loop, we’re now seeing it through a different set of eyes. We know some things he doesn’t, which means we’re more invested in him fighting off these bad guys so he can find that information and use it to get out of this.

There’s one scene in particular I want to highlight because it’s one of the most memorable scenes in the script. That would be the scene where Roy proceeds to take pliers and pull each and every one of his teeth out so that his friend can inspect them for bugs.

Why do I like this scene? BECAUSE I’VE NEVER SEEN IT BEFORE. In fact, I’ve never seen anything like it at all. And I have tons of admiration for any writer who comes up with an original scene. Seeing as you’re competing against millions of movies to find something different, doing so is almost impossible. And most writers give up. Which is why most movies blow. Writers don’t want to put the effort in to find original scenes.

So how do you find these chupacabra scenes? Is it impossible? No. Not if you use something called “conceptual sequencing.” Conceptual sequencing is an A++ advanced screenwriting technique that only a few people know about. But I’m going to share it with you today.

I’m just kidding. I made that name up. It sounded cool though, right? But the technique is real. To find original scenes, you must IDENTIFY WHAT IT IS ABOUT YOUR CONCEPT THAT IS UNIQUE. Why? Because when you’re trying to find ideas that haven’t been in any other of the 10 million movies, you’ll always fail. But if you only try to find ideas that are original to THE TIME LOOP CONCEPT, it all of a sudden gets easier. They’ve only made 30 of these. You can come up with a scene that hasn’t been in 30 movies.

The trick is to then go into every scene and ask, “How can I use time looping to make this scene different?” Often, you won’t be able to come up with anything. And that’s fine. Not every scene needs to be unique. Just one every once in a while. In the tooth pull out scene, we had a character who suspected that the bad guys had planted a tracker in his tooth. Now the obvious scene here would’ve been to go to a dentist and have the dentist inspect his teeth for the tracker. Only problem with that? IT SOUNDS BORING!!!

So you ask the question, “How can I use time looping to make this scene different?” Well, Roy is going to die in an hour anyway. He doesn’t need his teeth. Especially because he gets them back when he wakes up tomorrow anyway. So he wouldn’t waste any time. He would just start yanking his teeth out right there. And that’s how you find your original scene.

To summarize: If you’re writing a script properly, there should be something about your concept that’s unique. Use that unique quality to find original scenes. If you write enough of these original scenes, your script isn’t going to feel like anything else out there, which means it will STAND OUT.

Another thing that’s cool about this script is that it has a good ending (spoilers follow). This is important because when you’re playing with high concepts, especially concepts that play with time, you’re expected to write a clever ending. It would be weird if you didn’t. So late in the movie, Roy figures out that Ventor didn’t kill his wife last night, like he’d always assumed. He killed her this morning. Exactly 14 minutes after Roy woke up. But Roy never knew that because for the first 14 minutes of his day, he was always running from crazed assassins.

Once he realizes that his ex-wife was killed 14 minutes after he woke up, he has a goal. He must somehow get to Dynow, infiltrate the company and all its security, then get to and kill Ventor, ALL WITHIN 14 MINUTES. It creates the perfect impossible ticking time bomb ending for a movie.

I really liked Boss Level. I probably would’ve given it a higher rating if this was one of the first time loop scripts. But I have to dock it a few points for being in a genre that’s grown ubiquitous.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When writing character descriptions, use words that have a dual-purpose. They’re both visual AND tell us who the person is. Carnahan is great with character descriptions. Here’s one for Ventor’s co-worker. “Ventor reaches toward BRETT, an overly tan, tribal-barb tatted, squared-jawed juicehead and his second-in-command.” Notice how these words achieve two things. “overly tan.” We can visualize that and imagine the kind of person who chooses to be overly tan. “tribal-barb tatted.” Again, a good visual and there’s a certain kind of person who likes tribal-barb tattooes. Even “juicehead,” while not directly visual, gives us a visual and tells us who we’re dealing with. So make sure you’re using two-in-one adjectives to elevate your character descriptions.

Genre: Horror

Premise: (from IMDB) A group of friends travels to Sweden to attend a reclusive mid-summer festival. What begins as an idyllic retreat quickly devolves into an increasingly violent and bizarre competition at the hands of a pagan cult.

About: Writer/Director Ari Aster was anointed to “next big thing” status when his intense not-for-everyone film, Hereditary, became indie studio A24’s biggest movie ever. Aster didn’t waste any time, using the buzz to launch his next project, Midsommar, immediately. The film didn’t perform as well as hoped, making $27 million domestically compared to Hereditary’s $44 million. Still, Aster’s now loyal following loved it, and it’s expected to do very well on digital.

Writer: Ari Aster

Details: 150 minutes!

I resisted seeing this when it came out because it was written and directed by Ari Aster, the writer of the worst screenplay ever, Hereditary.

But conflict lives deep within my heart as I’ve always wanted a great modern day horror film about cults. And while I despised the screenplay for Hereditary, I had to admit its trailer exhibited a talented directing eye. Then Martin Scorsese spent 30 minutes of a recent Q&A talking about how much he loved Hereditary and I finally said, “You know what. I’m going to see if this guy learned anything about screenwriting since his last film,” and popped Midsommar into the old Apple TV.

The premise for the film is a simple one. A 20-something girl, Dani, loses her sister to suicide. Incidentally, the carbon monoxide she used to kill herself also leaked into her parents’ room and killed them too. So Dani is one family down.

Her grad school boyfriend, Christian, is tagging along with his Swedish friend, Pelle, and a couple of other guys, to check out a mid-summer festival in Pelle’s rural Swedish village. Dani decides to join them and off they go.

There’s a strong Heaven’s Gate vibe to the white-clothed hippy community and yet nobody thinks to turn and leave. They can’t, of course, or else there would be no movie.

The people there seem nice (don’t they always), and invite everyone to a ceremony where two elders are brought to an overarching cliff to speak to everyone. Except they don’t say a word. They JUMP! And die. Splat.

In real life, our characters would sprint to the nearest airfield and stow away in the landing gear if it got them away from this psychotic Swedish Manson cult. But no, our characters choose to stay and see what these wily Swedes are up to next. Naturally, these things turn out to be nefarious and one by one, our characters die in awful ways.

Before we get to the script stuff, lots of people were surprised that this film didn’t do as well as Hereditary. Yet the reason is simple: It’s hard to pull horror off in the daylight. You can do it with zombies. But you can’t do it with much else.

The reason horror works so well is because the darkness activates the imagination. It offloads the work from the movie to the viewer. They get to fill in their own fears with what’s in the corner of the dark room, what’s at the bottom of the dark basement stairway, who that shadow belongs to at the end of the dark hallway.

You don’t get any of that with daylight. So you have to find your horror elsewhere, and that can be challenging. So when you see this big bright movie that’s being advertised as a horror film, it’s confusing. And people aren’t going to show up to confusing. They want a good idea of what they’re walking into.

Now from a cinematic perspective, Aster’s choice is exciting. There’s irony in the search for fear in daylight. And outside of some annoying directing choices, Misommar works. That’s because every viewer knows this place is bad news. So as long as you keep a log on the fire for the next looming threat, we’re going to be into it.

Surprisingly, the thing that makes Aster a bad writer also helps him. When your narratives are weak and unfocused, as both this and Hereditary are, it gives the story a natural unpredictability. If you’re not following any common act or scene beats, we’re not going to know what’s coming next. And that’s why I kept watching. I had no idea where this was going.

Aster also put a lot of work into the mythology of this village and it paid off. I trusted that whenever something happened that was tied to this place’s weird rules, it was authentic, because I could tell Aster did his homework. I mean there’s a giant barn where the entire inside is covered in a historic mural of this clan’s history. You can’t make that sort of thing up on the fly. You have to know it and convey it to the art department.

Which is what makes this movie so frustrating. If Aster took some time to learn screenwriting, he would be unstoppable. Cause as a visual storyteller, he’s quite talented.

To give you an idea of what I mean by bad writing, Christian comes up to one of the friends after the two elders kill themselves and tells him he wants to write his thesis paper on this clan. The friend gets mad, replying, “I told you already. I was writing my thesis about this place!” Not only did I have no idea that either of these two were writing theses before this moment. But I didn’t even know they were in school. That’s how poor the writing was. We’d find out major story components after the fact.

There were all sorts of character issues here. Why doesn’t Pelle warn his best friends that they’re about to watch two people kill themselves? Why wouldn’t he brace them for that? Tell them that if it’s too much, they might want to sit the ceremony out? I’ll tell you why. Because if he did, Aster wouldn’t have been able to write the scene.

A bad writer says, “Well I’m just going to do it anyway.” A good writer says, “I have to figure out a believable way in which he wouldn’t tell them.” Why do bad writers always go with the former? Because it’s eaasssssyyyyyieeer!! It’s easier not to do the work! Are you telling me I may have to sit down several hours a day for a few days until I come up with a believable reason for why my character wouldn’t warn his friends about this? Screw that. It’ll take too long!

But I think Aster’s taught me the secret to getting these daytime horror movies right. Just follow two rules. One, be weird. Be really really weird. You don’t have the darkness to hide behind so, instead, have a bunch weird crap happen. This is why Wicker Man is still the champion of this sub-genre. You’d have little kids joyously singing about sex through choreographed dances. Or naked women singing about boning you while banging on the other side of your hotel room wall.

The other tool to use is shock. And this is something Aster is becoming known for. I mean he killed a main family member in his last film by having her stick her head out the window and get it decapitated by a telephone pole. Watching an uninterrupted shot of a woman jumping to her death and her head splattering over a rock in real-time certainly jolted me awake.

Now Aster just needs to figure out character. I had no idea who Christian was throughout this. None. Is he a good boyfriend who will do anything for Dani? Is he a bad boyfriend who takes her for granted? Every scene would vacillate between those two extremes to ensure that you never knew the guy.

Seasoned screenwriters know that if a character is unclear, you go back to their introductory scene and you use that scene to make it abundantly clear who the character is. When we meet the Joker, what is he doing? He’s looking in a mirror desperately trying to squeeze his lips into a smile. I know more in three seconds of that scene about that character than I do about Christian from watching this entire movie. That says something.

I’m going to log this as a step forward for Aster. It’s more interesting than Hereditary. And I watched til the end, which says a lot since this is 150 minutes. But keep working on your writing man. Or find a screenwriter you connect with. That could really skyrocket your career.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the rental

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Here’s a simple test to see if your characters are acting realistic or not. If you were in their shoes, would you do it? If you had just watched two people jump to their death in a pagan ritual, would you stay for another three days? Or would you leave? If the answer is leave (which it is), then you need to come up with a realistic reason why the characters would stay. (This is why so many horror films have their characters stuck somewhere. That way, they never have to worry about this question)

Last week’s Amateur Showdown was basically a 3-way tie (14 and 1/2 votes for Money to Burn, 13 votes to Odyssey, and 13 votes to The Black Petrel) with some hints of suspect voting, which means I get to decide which of the three I want to review. I went back and forth between Money to Burn and Odyssey. I know that Jay (Money to Burn author) can write. And I get a sense through some e-mails with Alex (Odyssey) that he knows what he’s doing as well. When it comes down to calls this close, there’s only one solution –

FIRST. PAGE. SHOWDOWN.

[echo] showdown…showdown…showdown

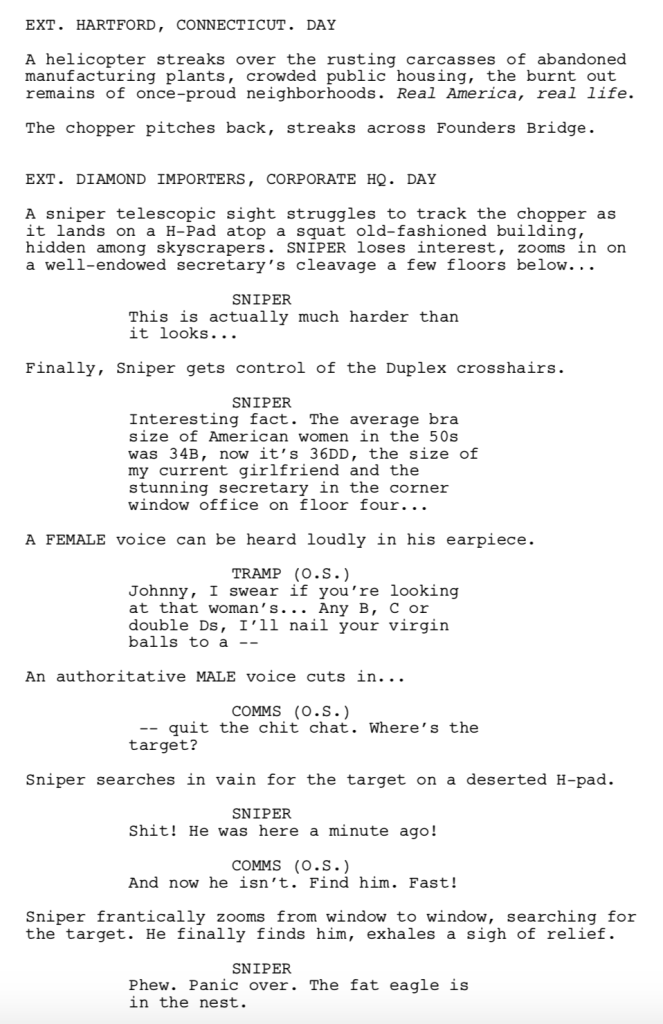

That’s right. Here at Scriptshadow when scripts need to be picked and the picking ain’t easy, the written word is the only solution. So here we go. This is the first page of Money to Burn…

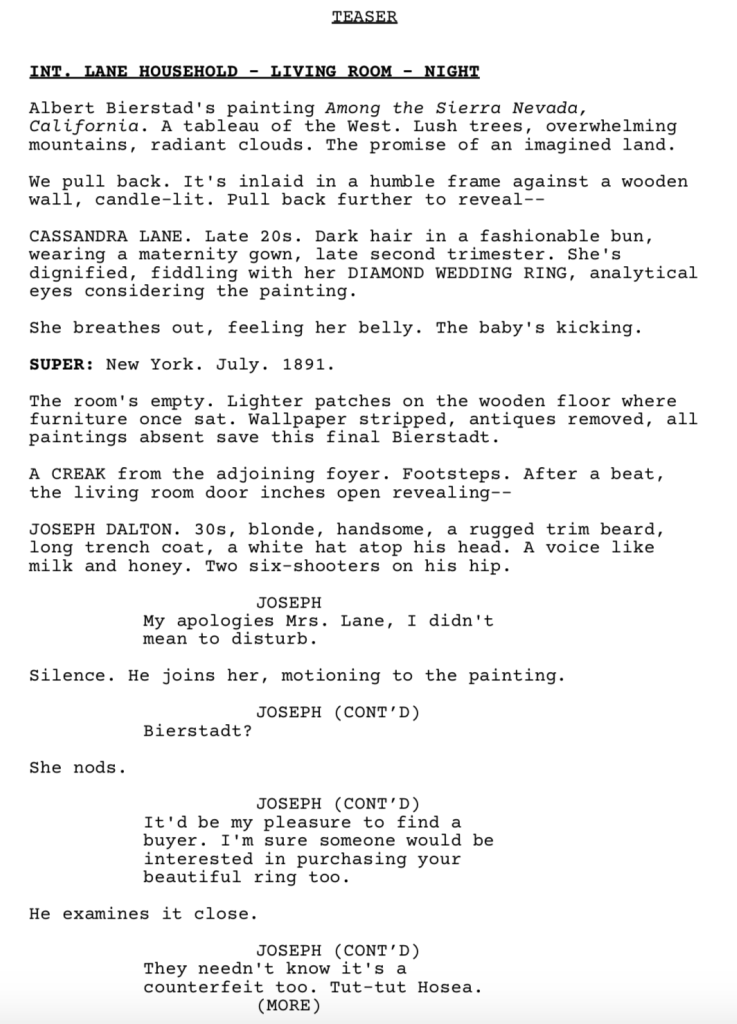

And here’s the first page of Odyssey…

Let’s start with Odyssey. Its opening is fine for a movie or cinematic TV show. I can envision the gentle dolly back of the camera from the painting and into the room. But as a script opening, it’s not very good. Scripts aren’t about camera moves. They’re about grabbing the reader. With that said, the writing is strong and detailed and I feel like the writer has a good grasp of the craft.

Moving over to Money to Burn, we’re in a helicopter, a sniper’s looking for his target. Something’s happening! This is a much better opening – dropping us into the thick of things. But like any good Amateur Showdown, there’s a twist. I look to the top of Money to Burn and see… 123 pages??? For a heist flick? That’s a loonnnng script. And Jay’s been at this for awhile. He should know how much high page counts affect readers.

I’m torn about which one to go with but when reading one script gives me an entire extra hour to my evening (Odyssey is 63 pages), that’s the script I’m going to choose. So I’m going with Odyssey.

Genre: TV Pilot/Western

Premise: A fierce pregnant widow makes a deal with a degenerate grave-robber to help her escort a herd of cattle across the Old West while the psychotic creditor that drove her husband to suicide and murdered her father stalks her across state-to-state, determined to make her pay up, or worse.

Why You Should Read: My bread-and-butter trademark is to take a tried and tested genre and write a new interpretation of old tropes. I think we all love westerns for the grizzled stares, the melodramatic music, and the collective fantasy of a lawless land. I do too. But I’m more interested in what the genre can do in the modern-day, not confined by what your Dad might like to watch on a sleepy Sunday afternoon. Odyssey is a pilot for a mini-series that honors what has already been done in the genre, but also takes it forward into new, exciting directions.

Writer: Alex D. Reid

Details: 62 pages

it’s 1891 and 20-something Cassandra Lane is pregnant. Being pregnant back in the 19th century was no picnic but you know what’s less of a picnic? Joseph Dalton, the mean-mugging creditor who Cassandra’s husband owes 5000 dollars to. Joseph’s shown up to the couple’s home in New York to get his money. There’s only one problem. They don’t have it.

After yelling at Cassandra for awhile, Joseph goes upstair to confront the man in question, Hosea, who, when confronted with the reality that he’s never going to find a way out of this, blows his own brains out. That cowardly move suddenly transfers the 5000 dollar debt on Hosea’s head, and puts it squarely on Cassandra’s. Isn’t that special.

Cassandra manages to flea New York and go back to her home state of Kansas. It’s here where she reunites with her widowed father, Nathaniel, who’s having money problems of his own. He can barely pay rent. Yeah, living back in the 19th century pretty much blew. Between your house burning down every month and contacting polio several times a year, you were constantly getting swept away in the Johnstown Flood.

That big fat meanie, Joseph, along with his gang, follows Cassandra all the way to Kansas and kills her dang dad! It looks like Cassandra’s going to be next. But when the gang members carry Cassandra out to shoot and kill her, she’s saved by a grave-robber named Dante, who, ironically, was planning on grave-robbing her father. But this is far from friendship at first sight. The very next day, Dante steals Cassandra’s father’s cattle, which he plans to take to California and sell.

Back at home, Cassandra is visited by yet another nasty presence, a bounty hunter looking for Dante. When he realizes Dante is long gone, he tortures Cassandra, who uses every last bit of grit and spittle to escape and kill the dude. Afterwards she steps outside to see, guess who? Dante. Who’s had a crisis of conscious. Seems he’d rather herd these cattle to California with their rightful owner. So off they go. But little do they know, the evil Joseph is on their trail.

I had mixed feelings about Odyssey.

I was not a fan of the first scene. It was written like Cassandra and Joseph were alone. Joseph’s creeping up on her. We’re thinking she might be in danger. But then, the guy they’ve been talking about this whole time, her husband, was upstairs. Just kicking it by himself. If he’s here to see that guy, why is he talking to Cassandra? So then we go upstairs and have a secondary scene in the house where Hosea is flinging a gun around, threatening to kill himself, and finally does it. The dialogue here felt very soap-opera-ish. On the nose. Overly dramatic (“I can’t even look after my own goddamn wife and child from–from fucking PARASITES like him! What the hell am I if I can’t do that, huh?” “The man I love.”). It didn’t set the pilot off on the right foot, that’s for sure.

And a funny thing happens when the first scene doesn’t work. It triggers a psychological shift in the reader where they lose a little faith in the writer. They don’t move forward with as much confidence. But hey. I was on the fence with Cop Cam for a while and that script turned around quick. So this was far from a script killer.

What annoyed me, though, was the jumping around in time. I don’t mind storyline jumping that much, but it has to have a clear purpose behind it. And this felt more like we were scrambling up the timelines in an attempt to add some extra flash to fairly plain story. I still don’t understand why we were cutting back to Cassandra, her dad, and some Indian kid. I never cracked the importance of that storyline.

The pilot works best when it’s sitting in its scenes and letting the characters push towards potentially ugly situations. Like when the bounty hunter has Cassandra all alone in her house. It’s one long scene but it properly builds a sense of dread and a fear that Cassandra isn’t going to make it out of here alive.

I also liked Alex’s fearlessness. This isn’t your grandfather’s Western TV show. People die in horrible ways and Alex isn’t afraid to show it. Heck, even Cassandra’s poor dog is offed. And while normally, I’m not a fan of animal deaths, it serves a purpose here, which is to make clear to the audience, nobody is safe in this world. And that’s important in a TV show because we’re more likely to watch if we think people are legitimately in danger. Isn’t that when Walking Dead and Game of Thrones were at their best? When you had no idea who was going to make it out of an episode? Once it was clear every main character was getting out of a season alive, those shows went south.

It’s not easy for me to grade this pilot because there’s plenty of things to celebrate. But between the weird time-jumping and the lack of anything that truly set this Western apart from anything I’ve seen before, I’d have to say this just misses a ‘worth the read.’ But Alex should be proud. There’s plenty of skill on display here.

Script link: Odyssey

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m always looking to see if I can simplify a story. And something bothers me about the structure here. We move from New York to Kansas…. so we can move from Kansas to California. Why can’t we redistribute the whole story so that we start in Kansas? That way it’s simpler. We start the movie in Kansas and the pilot is used to set up the rest of the show – which is to move to California. And here’s why plot simplicity is important. The way it is now, Alex is forced to create all of this exposition to explain New York and Joseph and her husband and her father. If we could build this dilemma in Kansas, we wouldn’t have to use precious screenplay energy to rehash a bunch of backstory.

I received an interesting e-mail last week which I initially disregarded but couldn’t stop thinking about. It was a beginner screenwriter who said he’d been reading my site and others for the last three months in order to learn everything possible about screenwriting so that he could write a great screenplay his first time out. He wanted to know my thoughts on if that was possible.

If you’ve been screenwriting for any length of time, you’ve heard the old coda that your first script is going to be terrible. And, actually, that your first five scripts are going to be bad. My experience with this statement has been that it’s true. Screenwriting is a deceptively difficult skill to learn. It looks easy because you don’t have to write as many words as a novel. And everyone assumes that if they love movies, they can also write them.

What these people eventually find out is that there’s a mathematical component to screenwriting (seeing as movies need to be 2 hours long) that must be effortlessly intertwined with a creative side of screenwriting, and mixing these two elements naturally is challenging. And when you really get down in the trenches, you learn that a reader’s attention span is way shorter than you think it is. Which is why most people reading your script won’t even give you the courtesy of reading past page 1. Look no further than Amateur Showdown for that.

But I tried to look at this question from a unique point of view – one might say, a movie concept point of view. I’m given a classroom of 30 people who have never written a screenplay before. ONE of these writers MUST sell a screenplay within the next six months or I’m dropped in a vat of acid by the evil screenwriting super-villain, Juan Augustian. What would I tell these writers in order to best give myself a chance to live? Or maybe the more interesting question would be, do I think there’s any chance at all that I would live?

I’m going to wait til the end of this post to answer that question. And, in the meantime, I’m going to tell you what I would tell those 30 aspiring screenwriters.

The first thing you need to do is read five produced screenplays cover-to-cover, five purchased but not yet produced screenplays cover-to-cover, and five amateur screenplays cover-to-cover. This is mainly to familiarize yourself with the screenwriting format and to compare the differences between amateur and professional work. But also, it’s to track when the story has you captivated and when you’re bored. You want to write down, in detail, why you believe you’re feeling this way.

Say you’re on page 20 and you’re bored. Why. Is it because nothing exciting has happened yet? Or is it because you don’t like something about the main character? If so, what don’t you like about them? The more detail, the better. Are they a sad sack? Are they passive, always allowing life to dictate their actions? By doing this, you’re creating a roadmap for what to avoid when you’re writing your own hero.

I should note that most amateur screenwriters have never read five amateur screenplays cover to cover. Which is sad. It wasn’t until I started reading amateur screenplays that I realized how many of these terrible mistakes I was making in my own scripts. Honestly, it’s like seeing the Matrix of Screenwriting. The green code disappears and is replaced by total clarity. I would even encourage writers to read more than five amateur scripts. But you should read at least five.

After you’ve read all your screenplays, it’s time to come up with a concept. This is probably the most important thing you’ll do. Not just because a good concept gets people’s attention. But because a good concept gives your script a framework whereby it’s easier to write good scenes. Say you like dinosaurs. Well, the concept of visiting a dinosaur island in modern day has more potential than a concept about a paleontologist who’s trying to prove his theory that dinosaurs were almost as smart as humans. There’s a very specific reason for this. In the first example, you can imagine tons of good scenes. In the second, all the scenes you’re imagining revolve around research and writing and conversations with other people. Which means you’re going to have to move mountains to come up with entertaining scenarios. You’re writing a MOVIE so you want an idea that gets people imagining a great movie.

Next up, keep things as simple as possible. One of the hardest things for new writers to manage is too many characters and too much plot. You can see them struggling right there on the page as you’re reading it. To avoid this problem, keep your story simple so you have a reasonable chance of staying in control. No complicated timelines. No overwhelming character counts. No jumping to 50 different locations throughout the story. You want a story that’s manageable.

Now I want to be reasonable here. Every good story has one element that’s troublesome. For example, 500 Days of Summer. It jumps around in time a lot, which is something I’d ordinarily steer a new screenwriter away from. However, that’s what makes the concept fun. So you have to bend somewhere. But make sure that troublesome component is the only troublesome component. You’ll note that 500 Days of Summer, outside of the jumping around, is about two characters in a relationship and that’s it. So it’s still manageable. If the writers would’ve added four other relationships that were also jumping around, the script would’ve imploded.

An ideal concept for a first time writer would be something like Murder on the Orient Express. Yes, it has a fairly large character count. But it’s high concept and it takes place in a contained setting – a train. Also, the story engine does a lot of the work for you – someone’s been murdered and they need to figure out who the murderer is. When you have crystal clear concept like that, it’s easier to write the characters since you know what everybody is trying to do (solve the murder).

The next thing I would do is try to come up with a really interesting main character or secondary character. A great character is a screenwriter’s best deodorant against a sub-par story. That’s because if you write an interesting character, we’ll want to watch them through anything. They become the focus of our interest. Not so much the plot. Think Joker. Think Monster. Think Nightcrawler. Think Venom. Think Lizbeth Salender. Think Fight Club. As much as I gushed over “Yesterday” in the newsletter, one of the things that held it back from being great is the fact that all the characters were safe and normal. There wasn’t anybody truly interesting.

And I’ll make you this guarantee right now. If you have a good concept and an interesting main or secondary character, you will sell your script. Cause those are the two big ones. A producer’s eyes will light up because they know the movie is both marketable and can fetch a great actor.

A few of you may be calling me out on that. “Oh sure, Carson. I’ll just write an all-time great movie character. Awesome advice. I never thought of that.” Fair play. Seasoned screenwriters know that creating strong characters is one of the hardest things about screenwriting. So here’s a hack specifically designed for the new screenwriter. Think of someone you know personally, or who you’ve met in your life, who you’d consider an extremely interesting person. Then use them as the inspiration for your character. We’ve all met some wild people. Why not capitalize on that? Put them in a movie! It’s not as good as creating the character from the inside out, but it’s way better than some plain average Joe.

Finally, come up with an idea that does the work for you. That means give your character a clear goal. Make sure the goal has major consequences attached to it. And make sure there’s some immediacy to the story – what needs to happen needs to happen NOW. Not in three years, not in three months, not even in three weeks. Now! If you create a framework that follows these rules, your hero will always have something to do. “Nightcrawler” is a good example. Louis Bloom wants to become the best nightcrawler in the business. When you have a goal that’s this clearly stated, you’re never going to be confused about what happens next, because you only have to ask yourself one question: “What does Louis Bloom need to do to get closer to his goal?” That’s what I mean by coming up with a concept that does the work for you.

Do I think it’s possible to write a great screenplay the first time out? If you follow these rules and you have some real talent? You have a chance. It’s a small chance. Probably around 2-3%. But it’s better than every other beginner’s chance, which is somewhere around .00000001%. So it CAN be done. Will you do it? Let’s find out!

Genre: Drama

Premise: A young woman gets a job at an investment firm where she’s the only African-American at the company.

About: This script made last year’s Black List, finishing with 7 votes. The writer, Meredith Dawson, wrote on Mindy Kaling’s Hulu adaptation of Four Weddings and a Funeral. She also wrote one episode of The Mindy Project 2 years earlier.

Writer: Meredith Dawson

Details: 107 pages

What I was hoping for when I opened this script was something akin to a workplace “Get Out.” Not only would that be a great pitch, but it’d probably make a good movie. If a friend told me, “You have to see this movie. It’s like Get Out, the New Girl at Work version,” I’d throw that in the Netflix queue right away.

Unfortunately, that’s not what we get. And I’m trying not to hold that against the script. One of the first lessons they teach you in review school is to review the movie you saw, not the movie you wish they’d made. I’m not sure that applies as much on a screenwriting site because sometimes the best way to explain something is to show how you could’ve done it better. And there’s a lot here I think they could’ve done better. Let’s take a look.

Naomi is a 27 year old African-American recent graduate of Stanford Business School who watches way too much Frasier on Netflix. On the night of her graduation, she hooks up with a gorgeous bearded white guy named Ben (page 9). The two are going their separate ways in life, however, so after they sleep together, they don’t talk again.

Naomi then starts her job at Harvey, Larter, and Saw, a venture capitalist firm where she quickly finds out that she’s the only African-American there. No worries. Naomi is used to this dynamic. But what she isn’t used to is when GUESS WHO shows up to team with her on her first job? That’s right, Ben (page 26). It turns out he works here as well!

Despite her attempts to keep her private life separated from her career, Naomi can’t help but fall into a steamy relationship with the sexy Ben. But Naomi’s beta-male co-worker, Nick, who secretly loves her, warns Naomi that Ben is bad. “How?” She asks. Nick says he knows these things and just has a feeling.

Noami and Nick put together a proposal for a new company to finance but Naomi’s boss, Iyana, flippantly rejects it. Weeks later, during a big company party, Naomi is shocked to see that Ben has brought a date. But not just any date. His girlfriend of six years (page 62)! Needless to say, Ben and Naomi’s relationship sours quickly.

But it gets worse. Ben tells Iyana she should invest in the same company Nick and Naomi liked, and this time Iyana likes the idea. So much so that she puts Ben in charge. Naomi asks Iyana what’s up and she says Ben was just more convincing.

Later, Naomi goes to a business dinner meeting with a client they’re trying to sign, an older man, and he puts his hand on her leg (page 88). Noami tells Iyana about it but Iyana does nothing. Disgusted with the way she’s been treated, Naomi decides to let the press know just how little her company cares about keeping women safe.

You’re probably wondering why I included page numbers in today’s summary. I did so for a specific reason. These are the only plot points in the script. By plot points I mean major plot developments that send the story in a new direction. Page 9, page 26, page 62, and page 88.

Four plot points for the entire movie doesn’t provide enough dramatic entertainment for an audience to stay invested. These are movies. They’re not real life, where it takes time for big things to happen. In movies big things need to happen consistently. We go nearly 40 pages between Ben’s arrival at the company and the reveal of Ben being in a relationship. And I would even argue that that’s B-story stuff. It shouldn’t even be the main plot.

Another issue is that there isn’t enough conflict. Conflict is the screenwriter’s best friend. You should always be looking for it. Your hero should be encountering obstacles and problems and issues from every direction. That’s what makes watching characters interesting, is seeing how they deal with the things that are thrown at them.

The first 60 pages of “Spark” is basically Naomi loving life, a party on the page, a 1 hour drive down Easy Street. That’s unacceptable in a feature screenplay. It also makes the ending weird. Because for 60-80 pages, this is a light soap opera. Girl meets guy. She falls for him. Turns out he’s in a relationship. So to then make the ending incredibly serious with major sexual misconduct allegations felt like it came out of nowhere. Had there been more conflict at work and had the tone been darker throughout, it might’ve worked. But in its current iteration, the final act felt like a different movie.

How would you fix a script like this? For starters, you have to understand the 3-Act structure. Something big needs to happen at the end of the first act. Something that sets the story in motion. Today’s writer made Naomi starting work the end of the first act. That’s not enough. It’s just continuing the good vibes. A seasoned writer would’ve gotten Naomi into work within the first five pages. And they would’ve had the sexual misconduct happen at the end of the first act. The movie, then, would be about dealing with the ramifications of what happened, trying to get someone to do something about it while, at the same time, trying to maintain your professionalism, your relationships, and your job. I haven’t read the Roger Aisles script that’s coming out but I can guarantee you the first instance of sexual misconduct isn’t going to happen on page 88. What this essentially means is that Spark has an 88 page first act. And that’s just not understanding screenplay structure.

There were other problems as well. 10-line paragraphs (this is one of the easiest ways to spot a new writer), a lack of clarity in the genre (is this a drama, rom-com, a dramedy?). All the business-speak consisted of buzz words and buzz acronyms minus the necessary specificity to connect it to the story (“But HEAL is puttering out high dividends for a company as young as it is AND we’re on track for FDA approval within the next year.”).

With that said, the writing itself was strong. Unlike that awful script I reviewed in the newsletter where I could barely get through a sentence, the prose was never overbearing and the writing was insanely easy to read, to the point where my eyes were shooting across the page and I never got lost.

But this script is not ready for primetime. There are too many Screenwriting 101 mistakes here. I was hoping for more.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: As a screenwriter, one of the things you have to be good at is getting a lot of story across quickly. Take the storyline of Naomi sleeping with Ben and then finding out he works with her. That took 26 pages here. In the Gray’s Anatomy pilot episode, they use the same storyline. And yet it took them less than 8 pages. And that was a TV show! Where they don’t even have to move fast. Whatever you think is the proper pacing for moving your plot along, it could probably move along faster.