I continue to work hard on the Scriptshadow Dialogue Book. One of the most time-consuming parts of the process has been cross-checking all the tips against my favorite movies.

I’ll watch a favorite movie and, with each scene, make sure that the dialogue being spoken doesn’t contradict anything I’m saying in my book. For the most part, it’s gone great. Everything that I’ve watched lines up perfectly with the tips I’ve written.

And then I read Sideways.

For those of you who don’t know, Sideways is a movie that came out in 2005 about two friends in their 40s, eternal pessimist Miles and sex addict, Jack, who go on a wine-tasting weekend the week before Jack gets married. The screenplay, written by Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor, won the Academy Award for best adaptation.

In order to understand why this script threw a wrench into my previously perfect book, you must first understand the principle tenets I’m building the book around. Namely that every dialogue scene needs to be motivated by a character who wants something.

Typically, that something is a goal – such as needing advice or needing to confess – or the need to solve a problem – such as a car breaks down on the side of a deserted road; what do you do? But, mainly, there needs to be purpose in the scene, and that purpose needs to be driven by the characters.

Then I read Sideways and in the first half of the screenplay, there were, at most, three scenes that abided by this rule. Characters were speaking to speak. Sometimes just to fill up time. And I’m thinking… wait a minute here. This goes against everything I believe.

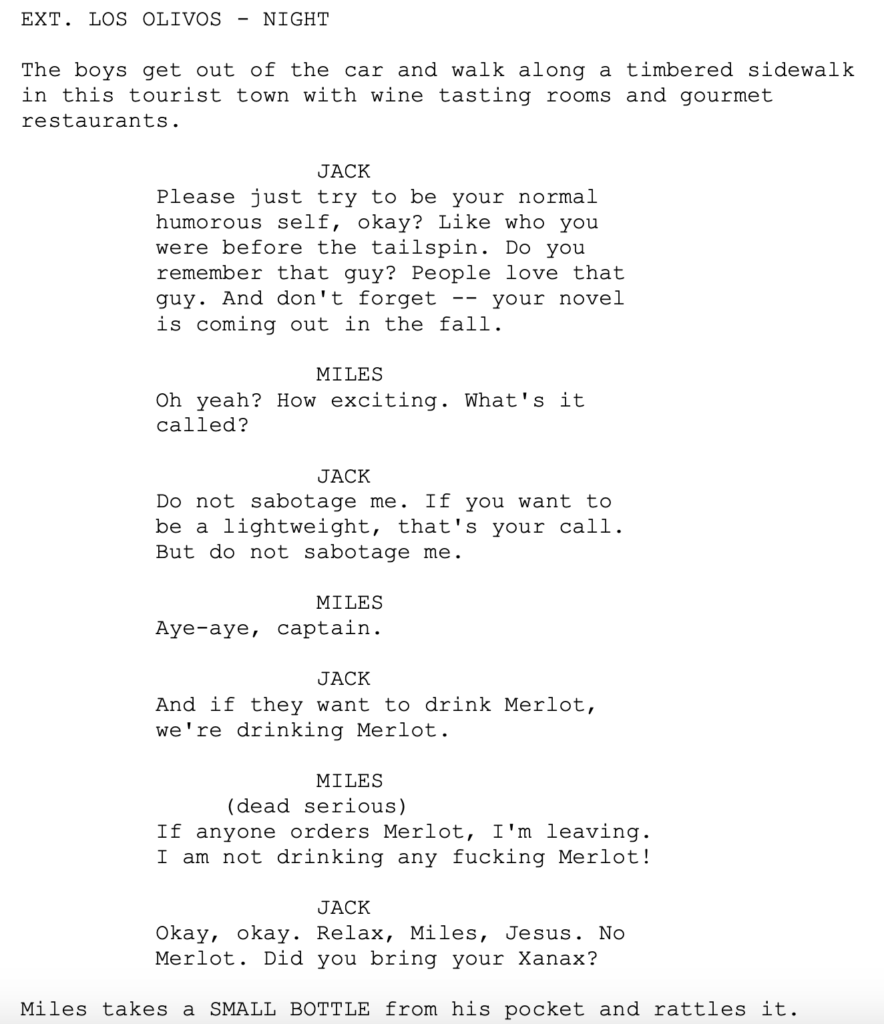

Here’s a scene from early in the script, when Miles comes to pick up Jack. Miles is thrust into a room with Jack, his fiancé, and his fiancé’s family. Notice how there’s no one here with any real goal (the cake tasting gets them in here but it’s not a true goal since it’s inconsequential). Nobody really wants to talk to each other. They’re just talking cause they’re stuck in the same room for a moment.

Then here’s another scene where Miles and Jack are having dinner with two women they recently met. Note how nobody really has a goal here. Sure, Jack wants to get laid and Miles likes Maya. But nobody has a specific goal in the scene. It’s basically just chit-chat.

Some might say, “Well, the goal it to decide on what they’re going to eat.” Yeah but that’s not a real scene goal. Ordering in movies is inconsequential, as is the case here as well. Does it matter what they order? No. So it’s chit-chat. It’s the stuff you usually leave out in screenplays.

Now, to be fair, Sideways is a high-brow movie written for well-educated folks 40+ years old who live on the Upper West Side or Beverly Hills. And it’s an indie film. It’s not meant to pull you in and bombard you with drama every five minutes like a big-budget Hollywood film. So the rules are a little different.

With that said, the dialogue does work. It’s fun listening to these friends banter back and forth for two hours. So what’s going on? How is that happening?

There were a few things I learned.

First, I came to realize that the scene goals in indie films can be softer (or more subtle) than in mainstream films. They don’t need to be as big of a deal. So while in a Hollywood movie, the goal of a conversation might be to figure out how to defeat Vulture before he destroys the city, in an indie movie, the goal might simply be to teach another character how to taste wine.

I do think soft character goals in scenes are dangerous. They’re more likely to result in boring conversations. For example, go write your own scene where one character teaches another character how to taste wine. Just how entertaining can you make that dialogue? Especially when nothing’s at stake in the scene.

But a skilled dialogue writer has tools in their toolbox that you don’t yet have and, therefore, know how to navigate these softer scenes to still make the dialogue work.

That leads me to the second thing I discovered, which is that Payne did something long before any of his scenes were written that ensured the dialogue would be entertaining. He made Miles and Jack the most opposite of opposites ever. Miles is a pessimist. Miles’ marriage fell apart. Miles’ book is never getting published. He’s a bitter shell of a man. Jack, meanwhile, sees possibility in everything. He’s optimistic. He’s about to get married. He loves life and loves meeting people. They are polar opposites.

This ensures that even if Payne never once comes up with a scene that has a strong character goal and actual consequences, that the scene is still going to be entertaining on some level due to the fact that these two will never see eye-to-eye. Every conversation they have is going to have a push and pull to it.

One of the key tenets of my book is, “Conflict solves all.” Because, if all else fails and you’re not doing many of the “proper” things needed to make your dialogue work, conflict can save you because when two people aren’t on the same page, there’s at least going to be some push and pull in the scene that will generate drama. And that’s what Payne so wisely does here. He bakes conflict into the Miles-Jack relationship from the start to ensure that, even when the plot isn’t humming, the conversations will still be entertaining.

Another thing I learned is that a character goal can be extended out beyond the immediate scene. So, in that scene above where the four characters are having dinner, Jack’s ultimate goal is to bed Stephanie. Originally, I was under the impression that dialogue goals needed to be scene specific. But, in this case, the goal is going to take several scenes and that’s okay. This is just the first of those scenes. Therefore Jack does, technically, have a goal. It’s just softer. It’s to establish sexual chemistry in order to get laid later on.

Finally, I learned that there are actually scenarios where nobody having a goal helps the dialogue. In the first scene that I posted, Miles doesn’t want to be talking to Jack’s in-laws. Jack’s in-laws don’t necessarily want to be talking to Miles. I guess they might be a little curious about him but they seem more focused on being polite than anything.

But that’s the reason the scene works. Because dialogue can be fun under awkward circumstances. The fact that nobody actually wants to speak is what makes the speaking fun. Cause we’ve all been in those situations. We’re stuck in a conversation we don’t want to be in and we just try and survive it. The desperate attempts to survive the conversation, wondering when the misery will be over, are what make it funny.

The more I study dialogue, the more complex I realize it is. But it’s really fun to keep learning this stuff and I can’t wait to share the book with you guys.

Also, a new newsletter is hitting your Inboxes this weekend! I’ll be reviewing a big-bugdget screenplay written by two of the biggest sci-fi screenwriters in Hollywood. I never knew these two teamed up on a script so I’m really excited to read it. So if you’re not already on the list, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com to get on!

GET $100 OFF A SCRIPTSHADOW SCREENPLAY CONSULTATION! – I’ve read over 10,000 scripts. Done over 1000 consultations. I am the guy who can figure out the issues hampering your script AND HELP YOU FIX THEM so you can start doing better in contests, start getting more responses from queries, and start actually getting jobs in the industry! I have a 4 page notes package or a more detailed 8 page option designed to improve every aspect of your script, from your plot to your characters to your dialogue. I also give feedback on loglines (just $25!), outlines, synopses, first acts, or any aspect of screenwriting you need help with. If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s set something up!

Genre: Horror

Premise: A young black man fights for his life after taking a job at a white-owned beauty parlor, whose monstrous owners concocted a wildly popular shampoo that requires a sickening ingredient.

About: We’re going back a year to a high-ranking 2020 Black List script (17 votes) that I never got to. The script was adapted from the writer’s own short film.

Writer: Chaz Hawkins

Details: 103 pages

Ski Mask The Slump God for “O?”

Ski Mask The Slump God for “O?”

While reading “The Sauce,” I went back and forth, throughout the script, on whether it was a movie or not.

Yesterday we were talking about “movies” vs “scripts” and, at first glance, this is a movie. You’ve got a character who gets stuck in a dangerous situation and must get out of it. It’s got your concept, it’s got your goal, it’s got your stakes, it’s got your urgency.

However, the script is adapted from a short film. And that’s evident when you read it. Because it spends the first half of its length building up to the “sauce’s” reveal. It does this because it knows that once you reveal the “sauce,” the script becomes about escaping. And it’s hard to build a long escape story around people who are stuck inside, essentially, a warehouse sized room.

But we’ll get to that. First, let’s talk about the plot.

22 year old Jason lives in a city called Coolchitown, which may be short for Chi-Town, which may be short for Chicago. Or it may just be a fictional town. It’s unclear. Jason is reeling from two issues. One, his mother recently died. And two, he has extremely low testosterone, to the point where he needs to take steroid pills.

After Jason is fired from his uncle’s barbershop because his uncle can’t pay him anymore, Jason takes a janitor job at the new hair salon across the street called “The Sauce,” which specializes in making straight hair curly. And it’s all because of their secret ingredient, the “sauce.” By the way, many black men in the area have gone missing over the last two months. I think you know where this is headed. Or do you??

The Sauce is run by Priscilla and a group of gorgeous Greek women who are very secretive and who immediately love Jason. And Jason loves the place too! He’s making a lot more money here than he did at that barbershop, that’s for sure. But Jason wants to make more money. So when his best friend, O, and his former crush, Meddy, come up with a plan to steal from The Sauce, Jason is all in.

So they go there late at night, break into the safe, find 100,000 dollars, and think their lives are about to change. Well, they are. Just not the way they think they are. Curiosity gets the best of them and they open the private door that Priscilla said never to open. They’re shocked to find a giant orgy going on between white women and black men. And it doesn’t take much for O and Jason to join in.

Jason then wakes up, still inside this secret room, which appears to have powers that allow it to expand out into this giant “spa.” While O wants to stay here for the rest of his life, Jason wants out. And that’s because Jason’s medical deficiency – his low testosterone – is making him think clearly! He’s got to find a way out of here before Priscilla figures out a way to fix his Low-T problem and, in the process, permanently turn Jason into another “sauce” supplier.

I want to give the writer props here because the whole time we were building up to “what’s going on here?” I thought these Sauce women were killing black men and using their blood in some ritual that allowed them to create this perfect curly shampoo. I definitely didn’t think there were giant orgies going on to extract “their secret sauce” so to speak.

I always give credit to writers who can surprise me.

But let’s go back to my earlier issue of this being a stretched-out narrative. Something that all writers go through – I know I used to agonize over this when I was younger – is “does your concept have the legs to last an entire movie?” And it took me, probably, ten years of being around concepts and seeing them played out in screenplay form before I was inherently able to know if a concept had legs or not. It’s not easy.

But adapting 5-10 minute short films into features is about as hard as it’s going to get for a writer to create a feature length film that doesn’t feel stretched out. Which “The Sauce” is. It takes us all the way until page 55 before the orgy is unveiled. That’s 55 pages you’re stringing the audience along on a single carrot. Most audiences are just not going to be that patient. Especially these days.

And then you run into just as difficult of a problem. Which is, how do the characters escape this room and how do we expand that out another 55 minutes? You really feel that when you’re reading the script. You can sense the writer looking for ways to stretch things out (O takes Jason on a tour of the place?). And screenplays are supposed to read the opposite of that. They’re supposed to read like time is slipping away.

Now, to the writer’s credit, he does some pretty imaginative stuff with the mythology. I thought it was quite creative the way things were tied back to Greece and the Gods and the sirens, and how the workers were also birds, which led to some fun imagery.

But, in the end, if the pacing isn’t satisfactory, the reader or the viewer tune out. And the pacing here, especially throughout the first half of the script, felt like it was being stretched.

I’m not saying this can’t be done. Lights Out is an example of a 3 minute short film that went on to become a feature and make 70 million dollars. I’m just saying this is stuff you need to consider when you’re picking your concept. Or thinking of expanding a short film.

I have a writer-director friend who wrote this fun short movie about a guy whose car gets stolen at a gas-station and his kid is in the backseat. It’s the perfect concept for a short film because this guy has to chase down this car to save his kid. And my friend wants to turn it into a feature. But I don’t see how you do it. Because following a car with your kid in it is great for 7 minutes. But it gets old if you’re doing it for 107 minutes. He still won’t listen to me, lol, but, yeah, we all go through this because when we fall in love with ideas we only see possibilities, not problems.

Anyway, this script is okay but the slow pacing issues born out of a thin idea being stretched to the max kept me from giving it a recommendation.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned 1: The sneaky backstory character introduction. I’ve seen writers do this and it’s clever. What you do is you introduce your character not by describing them, but by giving us a little backstory on the character. It’s a cheat code to sneak some backstory in. Here’s how Jason is introduced.

JASON (22), black, a kid that could have made it out the hood but gave up before he saw the greener grass.

What I learned 2 – Don’t make obscure references in your scripts. You’ll be lucky if 5% of the readers catch them. Here’s an example from this script: “Agatha grins slowly, sexually like Herman Cain in one of his 2012 election campaign commercials.” Some people from yesterday didn’t know who William Hung was. William Hung has, maybe, the single most popular talent show audition of all time. And some people don’t know who he is. If people don’t know who William Hung is, they definitely don’t know who someone from a 2012 political ad is. Yet I see writers doing this all the time. You can include references like that IN DIALOGUE, because maybe it’s in that character’s personality to make obscure references. But you can’t do that when you’re talking directly to the reader. Because all you’re going to get is an annoyed eye-roll and the reader thinking, “Who the heck is that?”

Is today’s script killing the Black List?

Genre: Biopic

Premise: The true story of the aftermath of the most infamous audition of all time – William Hung’s “She Bangs” cover on American Idol.

About: This script finished with 9 votes on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Tricia Lee

Details: 125 pages

Somebody made an interesting comment to me the other day.

They had this cool idea for a script and noted that they were trying to figure out what direction to take it in. They said they were thinking about writing it for the Black List, which meant making it a slow burn, character driven, and more “cerebral.”

Or, he noted, he could “write a script that will actually become a movie.”

This characterization of the Black List struck me. That the writer thought of it as a compilation of scripts that will never become movies.

Because it didn’t used to be that way. The Black List used to gleefully tout how many of its scripts would go on to become films. But is that the case anymore? A lot has been written about how the Black List cares more about social causes these days than what it used to be about, which was compiling a list of the best scripts in Hollywood.

So I decided to do a quick unscientific look at a current Black List compared to an older Black List. I went through the 2019 Black List and counted how many of the scripts went on to become movies. I didn’t use 2020 or 2021 because scripts need time to get produced. But 2019 is still within the time period where the Black List had refocused its mission, leaning into more socially conscious screenplays and writers.

Here’s what I found. In the 2019 Black List, 8 out of 66 scripts became movies. That’s equal to about 8%. In the 2010 Black List, 36 out of 76 scripts became movies. That’s equal to 47%.

Now I know a few of those scripts from the 2010 list took longer than 3 years to get made but it’s clear to me that the Black List used to be a place where, if you made the list, you’d have an almost 1 in 2 shot of getting your movie made. Now it looks like that’s closer to 1 in 8.

What this tells me is that the writers have figured the Black List code out. They know that they can write scripts that have no shot at becoming movies but because the Black List loves those types of scripts, they’ll make the list. And since more scripts are being written to make the Black List as opposed to writing scripts that could be movies, the Black List has become more and more dominated by screenplays that aren’t movies.

Today’s script might be the perfect example of this.

The story is simple. William Hung is 21 years old in 2002, attending Berkley as an engineering student, when, on a whim, he auditions for American Idol, which was still early on in its run and Simon Cowell was fast becoming one of the biggest stars in the world for how mean he could be to aspiring singers.

An American Idol producer recognizes that she’s struck gold as soon as she hears the earnestness behind William Hung’s audition despite being a terrible singer and puts him through to audition on tape in front of the official judges.

It doesn’t go well.

Months later, when the show airs, William Hung is walking around Berkley and everyone starts approaching him, congratulating him on his audition. What quickly becomes apparent is that William is being made fun of, and the only one who doesn’t seem to realize this is William himself.

So when he’s offered a singing contract, he’s more than happy to sign it. His goal is to use this fame to make enough money to buy a house for his parents. Along the way, he’ll deal with fake friends, girls who use him, lots of ridicule, and even a woman who marries him and later takes half the money he earned from all his singing in the divorce. But through it all, William Hung always remains positive.

Let me start off by saying this script isn’t bad. It’s actually pretty heartwarming. The writer explores themes of celebrity and the pressures of being an Asian in America. And there’s something very sweet about William Hung as a character. His priority is spreading a positive message within a worldwide tsunami of negativity. It’s not reaching to say that we need more people like William Hung on this planet. Especially today.

But come on.

This movie is never getting made.

And while I don’t claim to know what’s going on inside the writer’s head, I’d be surprised if she said she wrote this script in the hopes of it becoming a movie. It’s a music biopic, the catnip of all Black List catnips. Just by writing that word – biopic – next to the genre category, the script’s chances of making the list went up 5000%.

You’re probably wondering what that means. “A movie?”

What’s the difference between a script that’s a movie and a script that is only ever going to be a script?

The answer is in the word itself: “Movie.”

“Move.”

A movie script tends to have MOVEMENT. Characters need to go places. They need to do things. And they need to do them NOW. Because if they don’t, something terrible is going to happen.

Several years ago I did a script consultation for a writer. The broad strokes of his story were that a guy comes back to his hometown for a weekend and spends some time with a girl he kinda likes.

This writer’s plan was to sell the script. And I kept telling him, in as many ways as possible, that this wasn’t a movie. Two people hanging out isn’t a movie. There was no hook here to build a marketing campaign around. It was just two people chilling. And nothing even happened between them.

I told him, literally, the only way this becomes a movie is if you’re the director and you find the money and make it yourself. Nobody’s going to buy this because it’s not something anybody can make money off of.

There’s no MOVEMENT. There’s no hook. There’s nothing important going on. Nothing with genuine stakes attached.

Maybe today’s script isn’t the best example because, at least with music biopics, you have famous music. And people will show up to a movie to see all their favorite songs performed from that group. But this isn’t even a real artist. Nobody’s pining to hear William Hung sing a Richard Marx song.

Another growing problem I’m noticing in the industry is that we’re in this weird state of having so much content that it’s easier than ever to convince yourself that your obscure script idea can get made. And to a minor extent, that’s true. There are more openings for content than ever.

But the principles for what sells are still in place. You got to have a concept with a hook, something that entices a mass audience. You gotta have that MOVEMENT I’m talking about – characters with goals that have stakes, and urgency. And freaking CONFLICT. That was another problem with the consultation script. There wasn’t enough conflict between the main character and the girl.

Even TV shows are becoming like this. They’re moving away from strictly character-driven stories to mini-movies. So they need that concept, goal, stakes, urgency, conflict as well.

Look.

There’s an opportunity out there for someone who wants to start chronicling the best scripts in Hollywood again. Cause The Black List clearly isn’t doing that anymore. And even though I thought this script was fine and it was a fast read, it shouldn’t be celebrated as one of the top scripts in town.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A few weeks ago, I pointed out the opening bully scene in Lord of the Rings as an example of a great way to create sympathy for your main character. Readers immediately like a character who’s being bullied. However, the reason the scene worked was that it found an inventive way to approach the bullying. This little girl lovingly creates a little origami boat and then floats it down the river. And some jerk boys start throwing rocks at it to try and sink it. It wasn’t the on-the-nose bully scene that I usually read in scripts. “Idol,” however, does contain the bully scene you DON’T want to write. William Hung is 10 years old. He’s singing badly. And then we get this line: “Suddenly, a FIST comes rushing toward William’s FACE and makes HARD CONTACT with his right eye. The fist belongs to ANGRY WHITE KID (10).” The “angry white kid” then starts yelling at him that he can’t sing. It’s the epitome of a stereotypical bullying scene, which is why it doesn’t work. Bullying scenes are one of the best ways to create sympathy for your hero. But just like everything else in screenwriting, you have to be creative with it. You can’t give us the on-the-nose, “anybody could think of this” bullying scene.

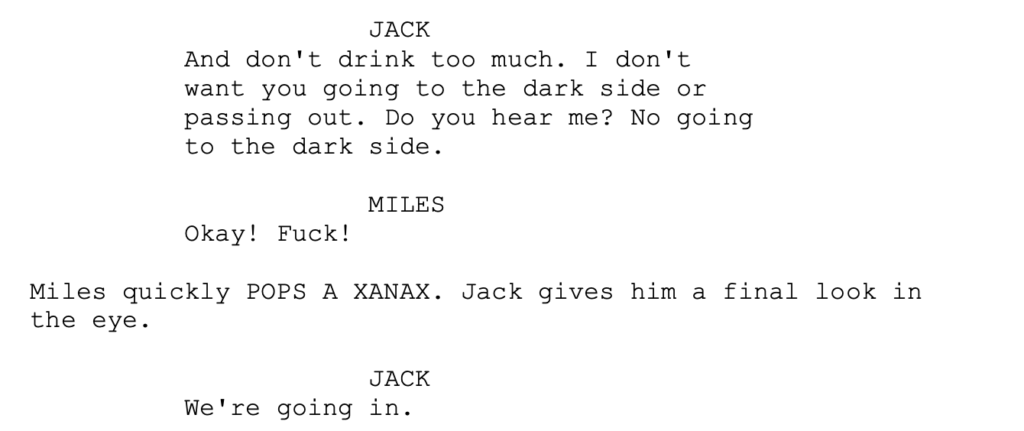

In this review, I’ll not only discuss if Don’t Worry Darling is worth checking out. I’ll reveal a potentially epic twist ending that the director and writer missed out on.

Genre: Drama/Sci-Fi

Premise: (from IMDB) A 1950s housewife living with her husband in a utopian experimental community begins to worry that his glamorous company could be hiding disturbing secrets.

About: After an endless amount of drama – Spit-Gate, Pugh-hate, Shia LaBeouf no longer being your mate — that became so obsessively covered that when it was reported Florence Pugh could only stay 15 minutes at the film’s Venice premiere because she was filming Dune 2, other news outlets questioned why Dune 2’s other big star, Timothee Chalamet, was able to come to the festival for an entire day — Don’t Worry Darling finally came out this weekend and made 20 million bucks. It was a haul nobody in the media liked because they couldn’t spin it into a good story. Had the film bombed, it would’ve been a perfect final chapter to all the behind-the-scenes drama. If it had been a hit, it would’ve been the ultimate redemption story. But, instead, it ended up right there in the middle at the amount everybody expected it to make.

Writers: The original script was written by brothers Carey and Shane Van Dyke. Olivia Wilde then brought in her Booksmart writer, Katie Silberman, to rewrite it.

Details: 2 hours long

Some would argue that the drama that went on behind the scenes of Don’t Worry Darling amounted to a better story than what ended up in front of the camera. The project is a rare studio release that came from a naked spec script sale, which is why I’ve been disproportionately obsessed with it.

Director Olivia Wilde, who had been unofficially propped up as Hollywood’s “Me Too” spokesperson after her beloved “you go girl” freshman picture, Booksmart, won the hearts and minds of Rotten Tomato critics, was set to level up with this movie, which was set to promote the power of feminism through its not-so-subtle message that men are a bunch of controlling jerk-faces.

I was particularly interested in how Wilde would approach the rewrite. For the record, I felt the original script was simplistic. And after seeing the excellent trailers for Wilde’s movie, it looked like she had solved that problem. The movie looked much deeper and more nuanced than the screenplay, which only increased my interest.

It’s the 1950s. We meet Alice and Jack, a very in-love young couple who live in a new community out in the desert. It’s run by this guy named Frank, who’s sort of like a 50s self-help dude on steroids.

After one of Alice’s friends tries to kill herself, Alice starts to question her own happiness and begins looking deeper into this Frank guy. He’s so smug. He’s so sure of himself. There’s something off about him.

After Alice spots a plane crashing in the desert, she heads off to help, only to find a strange house in the middle of nowhere. It’s here where she starts to suspect she’s not living in reality.

After her friends beg her to stop questioning Frank’s utopia, Alice finally learns the truth. (SPOILERS!) She’s living in a simulation, placed in here by Jack because she was too busy with work in the real world and never had time for him. So now she’s got to get out. But is it too late?

A photo more meticulously staged than The Last Supper.

A photo more meticulously staged than The Last Supper.

I was curious how Wilde was going to change the story from the original script.

She stated, in interviews, that she liked the original idea but implied it wasn’t up to par. Which is why she brought in her own writer. I agree with her that the spec wasn’t up to snuff. But now you’re on the clock. If you’re going to change it, you better make it better. Did she?

[Major spoilers follow]

In the original script, there was no question we were in the 1950s. And it was a “clean” 1950s. It wasn’t some special community. The reason that was such a pivotal choice was that it made the twist truly shocking. When we find out that it’s actually the 2040s and the 1950s world is a simulation, it was a big “WHOA” moment and the reason that the script became such a big deal.

For reasons I’ll expand on in a second, Wilde and Silberman ditched that. Instead, they created this situation whereby a bunch of people got up, left their lives, and went out to live in an isolated community. In one of a handful of badly written aspects of the script, it’s never clear if the people in the community left their modern (2022) lives to live this 1950s life, or if they left their 1950s life to live an even more isolated 1950s life.

Right there, you’ve committed a major script faux pas. You’ve made something that didn’t need to be complex unnecessarily complex. And I know the rationale for why they did it. They did it because they couldn’t have characters mixing with the rest of society. They couldn’t have them wanting to go on vacations or explore the world or head down to San Diego. So they created this isolated town in the middle of nowhere where nobody could ever leave. It allowed Wilde and Silberman to have total control over their characters.

The problem with this is, we know the twist pretty much after the first 10 minutes. We know this place is artificial because you’ve got a radio station that talks about tech-y things and you’ve got men who walk around in red jumpsuits and you’ve got husbands who go off to a secret Marvel underground base every morning.

You’ve tipped your hand before you’ve even got to the inciting incident.

The way you pull off a big twist is to not tell us any of these things. Which is the one thing that the original spec got right. They made us believe we were living in the year 1954. So that when we wake up in 2050, we’re like, “HOLY S#$%.” It was a total shock

Wilde almost made up for this weak choice by inventing the character of Frank, played by Chris Pine. Frank is like the world’s biggest self-help guru, to the point where he’s built his own community so he can infuse every aspect of his philosophy into the townspeople.

As the script goes on, this rivalry begins to emerge between Frank and Alice, taking a narrative that was fast decaying and resurrecting it. There’s a really fun scene late in the movie where Alice attempts to take Frank down in front of all her friends – to prove that he’s manipulating and lying to them. When the script focused on those two, it worked.

And about three-quarters of the way through the movie, I realized why Wilde had changed the original screenplay. This new character, Frank, infused the story with an omnipotent malevolence. There’s even a scene where Alice and Jack sneak off to have sex during Frank’s party and Frank catches them. He and Alice lock eyes in a sexy but uncomfortable way as she’s having sex with Jack but Jack never sees this.

And I thought, oh my God, Olivia Wilde came up with a way better final twist! That’s why she changed the original spec! I was convinced that instead of Alice waking up and finding out that Jack had incapacitated her to keep her in this virtual world, instead, Frank had created AN ENTIRE WORLD in order to control and be with all of these women.

I thought we were going to find out that none of the husbands were real. They were all Frank’s virtual creations, bodies he could slip in and out of whenever he wanted, allowing him to be with all of these woman. It’s basically the original twist, but on crack.

“Frank’s 1950 Simulation Pleasure Matrix.” Now THAT would’ve been a great twist.

But, instead, they stayed with the original twist, showing that Alice was being kept in a coma by Jack in his apartment so he could control her. Which no longer worked because you basically hinted that something like this was going on all the way back on page 10 and then kept telling us over and over again that it was coming. They found a way to neuter the twist as much as possible. Wilde may have introduced a new screenwriting term – the “twist neuter.”

But probably the biggest surprise here was that Wilde did a poor job conveying the original feminist message of the screenplay. Which is strange because the original screenplay was written by two men. And the rewrite was written by two women. So you’d think that Wilde and Silberman would’ve gotten that right.

The original script leaned hard into toxic masculinity and men wanting to control women. You don’t get that sense here. Jack was super in love with Alice. He’d clearly do anything for her. Sexually, he was more interested in pleasing her than her pleasing him. If the idea was to convey that Jack was this awful toxic male who wanted a robot for a wife, they did a really poor job of it. The original script made that much clearer.

Also, Alice’s best friend in the film, Bunny (played by Wilde) – it turns out she knew she was in the simulation all along. She actually CHOSE to be in the simulation because, in the real world, her kids died. Here, in the simulation, she could have her kids be alive.

So, wait a minute. Is this simulation designed so that men can imprison their wives and make them their virtual slaves, as was the focus in the original script? Or is this an “anything goes” simulation, where you can come here for whatever reason you want? Cause it sounds like the latter. And, if that’s the case, what the heck is your movie about?

It was sloppiness like that that kept intruding upon a really cool concept. Which made it frustrating.

But you know what?

I still recommend this movie.

And let me tell you why.

The cinematography and, overall, vision of the film, is really strong. Wilde deserves a lot of credit here. There’s a scene early on in the film where Jack and Alice are doing donuts in their car in the desert. It’s filmed from above and it’s not only beautiful, but it CAPTURES THE MOMENT. These were two drunk and in love people just enjoying each other’s company. That camera shot sold that better than any other shot they could’ve used. And there were a dozen moments like that in the film where the visuals truly sold the moment.

Definitely should start worrying, darling.

Definitely should start worrying, darling.

I also loved Florence Pugh. Even when the script hit choppy waters, she was a ship-steadyer. She’s just a great actress and she’s always 100% committed to her performance. She *was* Alice here. Just like there’s suspension of disbelief in screenwriting, there’s suspension of disbelief in acting. If the acting is weak, we’re pulled out of the movie. Florence Pugh is the opposite of that. She’s so in it we can’t help but be in it with her.

Chris Pine is also superb. I love him as an actor and I love him here. My only complaint was that he wasn’t in the movie enough. I get the feeling that if they had a couple more drafts, he would’ve been more present and we would’ve gotten that awesome final twist.

Even Harry Styles is solid. I’ve heard a lot of people say he’s a terrible actor but I didn’t see that. Who knows? Maybe all that extra attention Wilde gave him in the trailer resulted in him picking up a few acting tips. I suppose there’s a method to every director’s madness.

And then you gotta give credit to Wilde. She’s the one who cast these actors. She came up with the overall vision of this movie.

It’s just that the script wasn’t there. And, hey, welcome to the hardest part of making a great movie – writing a great script. Wilde is not alone in falling short in that department. She’s another casualty of the elusive puzzle that is nailing the screenplay

But I was right there with Alice all the way until the final frame. And for that reason, I say this film is worth checking out.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You don’t want to mess with a good twist. Good twists are rare. I come across one or two of them a year in the screenplays I read. Where I genuinely think, “Whoa. I did not see that coming! That was great!” So when you have that, you don’t want to overthink it, which is what Wilde and Silberman did. When you tell us at the outset that we’re in an artificial community, you put the audience on guard that something funny is going on. And it totally killed the power of this twist. Cause you’ve already put us on the “twist lookout” 70 pages earlier.

”Andor” asks, can a Star Wars experience without humor or padawans who hate sand entertain a rabid fanbase desperate for a good Star Wars show?

Genre: Sci-Fi Fantasy (TV show)

Premise: After a thief kills two employees from a large corporation while looking for his missing sister, he becomes hunted by the company on the backwater planet where he lives.

About: It’s finally here! Andor, the series. I’ve talked about it endlessly on the site. Tony Gilroy, who reportedly saved Rogue One from original director, Gareth Edwards, was gifted this show as his reward by Lucasfilm head, Kathleen Kennedy. Despite Gilroy insulting poor Star Wars every chance he gets and making the world’s most confusing statement about how the timeline in “Andor” is going to work, the show finally debuted today.

Writer: Tony Gilroy

Details: This review is for the first 3 episodes, which are each about 30 minutes.

Let us start by stating the obvious.

Before this series was announced, nobody was asking for a Cassian Andor show.

Which makes you wonder why they wanted to make it so badly. Lucasfilm has become infamous for terminating in-development Star Wars projects. So why were they so determined to get this one to the finish line?

Who knows? Most of you will probably say, “Who cares? As long as the show is good.”

To this, we can agree. I may not have asked for Andor but you can bet Chukhuh-Trok’s hunting spear that I’d love to be proven wrong. Probably more than anyone on this planet, I want to love a Star Wars show. And, from what we’ve been told, this show was made more for my demographic than any Star Wars project yet.

Are we ready for this?

Okay, let’s dig into Andor!

We meet Cassian Andor on some planet run by what Amazon might look like in a thousand years. Andor heads to a brothel where he appears to be looking for his sister, who may have worked here at one point. He doesn’t get any information on her so he leaves, and is immediately confronted by a couple of drunk-with-power Amazon employees. He quickly kills them both. Take that, Bezos!

Andor then heads back to his current planet of residence where he’s putting together some plan that is so secretive even the audience is not allowed to know it. In between scenes of him sneaking around and never allowing his voice to rise above 3 decibels, we cut back to when he was a kid on some planet living with a bunch of other kids and they discover a crashed ship.

Back at Amazon, a middle management type wants to sweep these employee murders under the rug. But a young ambitious dude in the company wants to kill the murderer in the hopes of propelling himself up the company ladder. So he recruits a dozen soldiers and heads off to Cassian’s planet to find him.

Cassian’s super-secret plan finally reveals itself when he meets with a mysterious rich guy named Luthen Rael. Cassian thinks he’s selling Luthen a star-thingamacalit, after which he’ll use the money to escape to some place far away. But it turns out Luthen has other plans for Cassian. Seeing how crafty this guy is, he wants to recruit him into his shadowy organization. Cassian has to make a decision fast – yes or no? He decides ‘yes,’ and that is the end of our third episode.

I was worried about two things going into this show.

1) That Cassian Andor isn’t a very interesting character.

And…

2) That this show would be way too serious.

I am sad to report that “Andor” confirmed both of these fears. Much like Tion Medon’s infamous botched dental visit, it’s a big fat whiff on each front.

Cassian is boring. He’s active, which is good. But if we never understand what our character is being active for, it doesn’t really matter. Being ultra-mysterious about who your main character is is one of the riskier moves in screenwriting. Because you’re basically saying, “You must like my character even though you know nothing about him or what he’s doing.”

There are examples of this working but they’re few and far between.

On top of this, the show is more serious than Emperor Palpatine when he’s drawing up his latest galaxy takeover. I think there were two attempted jokes in 100 minutes. And they were highly neutered. This is something I tried to warn the Star Wars fan base about. If you go super dark with Star Wars, it’s no longer Star Wars. An essential component of Star Wars’s makeup is fun. And this show is about as fun as when Malakili watched Luke kill his pet Rancor.

The closest to fun we get is the droid, B2EMO, and while I’d anoint him as my favorite character in the series so far, he’s got five minutes of screen time.

So is there anything good about this show, Carson?

I’ll say this. The dialogue is way better than any of the other Star Wars shows. There’s a level of sophistication you’re not used to seeing in this franchise. For example, there’s a scene where Andor comes to a work friend and asks him to provide an alibi for why he wasn’t at work earlier.

The dialogue is not framed in a clunky on-the-nose manner where Andor says something like, “I need you to help me with an alibi. I flew off to another planet which is why I missed work and now I need you to tell Boss Doug that I was hanging out with you.”

Instead, the dialogue is framed as if it really happened. So Andor immediately jumps in with, “I was at your house yesterday. We drank all night. You got mad at me because I bought cheap liquor.” “I would’ve yelled at you for bringing cheap liquor. We were drinking [different booze] instead.” In other words, they set up the alibi by speaking as if it really happened rather than asking for help and then coming up with a story together.

With dialogue, you’re always looking for ways to make the exchange different somehow. You want to avoid straightforward, Character A: “This is what I have to say,” Character B: “And this is how I respond to that” dialogue if possible. You could tell Gilroy is a step above all these newbie screenwriters that Star Wars has been hiring to write their shows. At least in the dialogue department.

Ironically, that same knowledge hurts Gilroy in the storytelling department. What usually happens when you get older as a writer is you show more restraint. You don’t feel the need to constantly titilate the audience every scene. You trust yourself and therefore take your time setting up the bigger plot developments.

But what sometimes ends up happening is you cross the Rubicon and show so much restraint that huge chunks of scenes go by without any payoff. We’re watching you setup and setup and setup and setup and it’s like, “Dude! Give us something for all the hard work we’re doing!”

I get the impression that Gilroy is playing to the highest common denominator here – the 60 year old intelligent veteran moviegoer who’s seen it all and is, therefore, willing to make the trek down Patience Lane. It’s a risky game to play in a franchise built off a never-ending supply of entertaining moments.

I would not have watched Episode 2 if they had only posted the first episode on Disney Plus today. I wouldn’t have even watched Episode 3 if they’d posted the first two episode on Disney Plus today. That’s how slow the story develops.

To Gilroy’s credit, all the things he was setting up in episodes 1 and 2 start to pay off in episode 3. This is the episode where the Amazon Corporation sends their soldiers to Andor’s planet to find and kill him. Gilroy did a really good job building up to this confrontation. What I enjoyed most about it was he made the whole thing just as scary for the Amazon soldiers as he did the locals. These soldiers are inexperienced. They’re 12 in a city filled with thousands of people. At any moment, if the people decide to revolt, they’re screwed.

That combined with the mystery of where Andor was going and who he was meeting created a tense atmosphere throughout the episode. It helped me see the potential of the series I was unconvinced it possessed in the first two episodes.

This has led me to a very confused place going forward with Andor, and with Star Wars in general. The Obi-Wan Kenobi show was a mess. Those rookie writers shouldn’t have been let anywhere near a franchise this big. The Boba Fett show was some of the worst writing I’ve seen on a show with that kind of budget. The Mandalorian is uneven but has some good episodes. It’s written well at times.

I would say that Andor is the most sophisticated written Star Wars show by far. I’m just not sure that’s showing the dividends it needs to after three episodes. Clearly, Gilroy knows how to write a scene. But is his overarching narrative as compelling as he thinks it is? I’m not sure. And is his main character as interesting as he thinks he is? Probably not.

I think this begs the question: Does Gilroy mesh with the Star Wars brand? Or is he pulling a Rian Johnson, where you hijack a franchise to tell the story you want to tell rather than the story that’s right for the franchise?

I’ll probably check back in with you guys at the season midpoint to give you better answers to those questions. In the meantime, tell me what you thought of Andor.

[ ] What the hell did I just stream?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Andor is yet another example of why all writers should seriously reconsider adding flashbacks to their story. We saw this in Boba Fett with the silly sand people flashbacks. We see it here with all this time spent on Cassian’s childhood that doesn’t tell us anything we couldn’t have already imagined ourselves. You have to ask the question, is what the flashbacks give you worth the momentum-stoppage they take from you? In this case, the answer is clearly no. The flashbacks dragged along. I’ll never say never. But, in my experience, flashbacks almost always take more from the story than they give.