Genre: Period/True Story

Premise: The true story of the murder of four American churchwomen in El Salvador in 1980 and the low-level American diplomat who teamed with his most dangerous informant to smoke out their killers. Based on Raymond Bonner’s work for The Atlantic.

About: This script finished on the Black List. One of the writers has written several Christmas movies. The other is writing an upcoming action film with Mila Jovovich titled, “Hummingbird.”

Writers: John Tyler McClain & Michael Nourse

Details: 121 pages

This feels like a Sebastian Stan starrer to me.

This feels like a Sebastian Stan starrer to me.

I think these writers got the memo from studios that with Stranger Things and Cobra Kai and Top Gun Maverick that: “Everything 80s is selling right now. We want more 80s!” I can see the pitch meeting now…

Writers: “You want more 80s? We’re got just the story for you. It’s set in 1980 in El Salvador! It’s about how 80% of the El Salvadorians don’t have a say in their government and then this innocent woman gets killed and then we follow the political machinations of the U.S. Embassy and how they ultimately solve the murder. It’s gonna blow everyone away.”

Today’s Studio Execs: “Uh, that’s not quite what we meant when we said everything in the 80s is selling.”

Writers: “Should we take that as a yes?”

Hey, I mean, it made the Black List, right?

Sister Dorothy Kazel is an American missionary in El Salvador in 1980. Not long after we meet this very cool motorcycle riding nun, we learn that her and three other nuns were raped and murdered.

This brings the American consulate into it, represented by a young man named Carl, who’s the only one at the American Embassy who seems to speak Spanish. He teams up with an angry Israeli agent named Idan to figure out what happened.

Betting odds are on a kill team led by an evil dude named D’Aubuisson. D’Aubuisson is going through the country randomly killing civilians for reasons that I’m not entirely clear about.

D’Aubuisson is obsessed with a group of pirate radio people known as “Radio Vencéremos,” who are warning everyone in the country where the Death Squad is. If you want to piss off a Death Squad leader, any preventative measure that will lessen his deathing is sure to rile him up.

Carl and his current bedroom buddy, Molly, slither around the El Salvadorian mainland asking a lot of questions. Their best bet is a guy without a name (“Killer”) who used to work in the Death Squad but hates it. To find D’Aubuisson, they’ll need to trust this dude. But is he leading them into a trap? Only time – and an obsessive amount of paying attention – will tell.

You know, I used to get upset with how many World War 2 scripts there were. The pile was endless. Don’t we have anything else to write about? I then read something like today’s script and it’s like, ‘Ohhhhhhh, this is why.’ Cause in Central American civil wars of the 1980s, everything is gray and unclear and random and we’re in El Salvador and we don’t really know why or what this has to do with anything on the world stage.

When you read a World War 2 script, it doesn’t matter if it’s about the U.S., Germany, Japan, Russia, France, Poland, or Great Britain, you immediately understand who’s good and who’s bad and can, therefore, participate in the story.

In a script like this, where the burden of investment is higher than One World Trade Center, you’re spending 80% of the time just trying to keep up with the exposition. There’s this Death Squad and maybe they’re working for the El Salvadorian army, or maybe they left because they *don’t like* the El Salvadorian army, and there’s a religious issue and also the Death Squad kills people to make statements, although it’s not clear what those statements are.

I know vociferous cinephiles say they love the grey area. But the grey only works when we understand each shade of grey. If each shade of grey is, itself, many shades of grey, we’re clueless as to what’s going on.

I mean this is some high brow grey-scale stuff here. We get exchanges like, “It’s not socialism, it’s communism. We know the Soviets are here. Dominoes of these backwards countries could topple straight up to Texas!” “That was our excuse in Korea – and Vietnam. But Communism evolves into facsimiles of Stalin; it’s a place marker for tyranny and eating its young. Socialism is different.”

I actually majored in world politics in college and I can only quasi decipher that exchange.

I suppose the counter-argument to this is, we live in an entertainment vacuum of Thor penis jokes and UFOs that turn into giant pieces of origami. You have to open up some slots for sophisticated adult fare somewhere. Which, I suppose, is a fair argument. But that’s the dilemma I was going through while reading this. Was the script too sophisticated for my taste, or is the subject matter uninteresting? Is the storytelling confusing?

Cause what often happens when you’re reading a script that you’re not enjoying is your mind starts wandering. And you dislike the script enough that, when you realize your mind is wandering, you don’t do the proper thing and backtrack to the spot before your mind started wandering. You instead keep reading despite not properly downloading what just happened during those two pages where you weren’t paying attention.

So is your confusion the writer’s fault or is it your own fault? Is it not the writer’s job, in the first place, to keep you entertained enough that that doesn’t happen? Or even if you dislike what you’re reading, do you still owe it to the writer to make sure you read and understand every single page? I’m curious what you guys think so feel free to give your opinion in the comments.

Another small thing I noticed in the script was this new trend of writers overwriting. Here’s an example from this script: “As he walks off, Dorothy looks back to the MOB being vomited from the church, to Diego, an 8yo boy, clinging to her motorcycle like it’s the only sanity left.”

There’s no need for “like it’s the only sanity left.” It’s a try-hard addition to the sentence that doesn’t need to be included. You *can* include it, of course. There are no rules in writing. I’m just telling you, whenever I read stuff like that, I roll my eyes a little. It feels desperate, like a writer trying to prove to the world that he’s a Writer, with a capital, “W.” More on that in the What I Learned section.

One of the most important questions anyone should ask before writing a story is, “Why would they care?” Why would an audience care about this story you want to write? If it’s a fictional story, is it unique and entertaining enough? If it’s a true story, what is it about this true event that makes it big/important enough that it must be told?

Now, of course, the answer to that question is subjective. But it’s still a question that needs to be asked because the ultimate goal here is that a large amount of people want to see your movie.

Every time I go through the variables here. El Salvador, 1980, 4 random women are murdered, I find myself shrugging. Of course, murder is bad. But there are literally hundreds of millions of murders that have occurred throughout history. I guess I’m having a hard time convincing myself that these particular murders are movie-worthy.

Maybe if there was some giant twist at the end, and it was the American government that killed them to validate an invasion or something, that might have convinced me. But there’s nothing that big here.

To the writers’ credit, they do have some fun with the dialogue, particularly between Carl, Molly, and Idan. But it’s not enough to offset a concept that I think is lacking enough punch to be a movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Going back to that earlier line – “As he walks off, Dorothy looks back to the MOB being vomited from the church, to Diego, an 8yo boy, clinging to her motorcycle like it’s the only sanity left.” Movie writing is about the VISUAL. Not the figurative. So if you’re going to make an analogy or use a metaphor, make it visual. For example, you might say, “As he walks off, Dorothy looks back to the MOB being vomited from the church, to Diego, an 8yo boy, clinging to her motorcycle as if it were a life raft.” It’s not a great line but at least the metaphor is focused on an IMAGE and not a state of mind, such as “sanity.”

Genre: Comedy/Sci-Fi

Premise: A disastrous Grindr hookup goes from bad to worse when a meteor unleashes a horde of aliens on New York and the two ill-matched men must depend on each other to make it through the day alive.

About: This is another breakout script for a writer, Thomas Kivney, who made it onto last year’s Black List with Max and Tony. Kivney got his MFA in screenwriting at the American Film Institute Conservatory. He previously worked at a literary scouting agency for four years, which is “where I started becoming more involved in film. It was a rewarding experience that meant getting to work closely alongside Warner Bros and Netflix, advising them on the acquisition of books for adaptation to TV and film.”

Writer: Thomas Kivney

Details: 115 pages

Perfect comedy vehicle for Jerrod Carmichael?

Perfect comedy vehicle for Jerrod Carmichael?

With Billy Eichner’s “Bros” (produced by Judd Apatow) coming out in two weeks, the LBGTQ community is looking to make a push into the mainstream instead of being relegated to speciality releases. If that film does well, expect today’s script to get immediately greenlit. To be honest, this should’ve been the movie Eichner made. It sounds a lot more fun.

Max and Tony match on Grindr and immediately agree to meet and bang at Tony’s place. If this is how fast all gay hookups come together, I need to seriously reevaluate my sexual orientation.

The hookup doesn’t go exactly as planned, though. Max can’t stop talking about his ex he just broke up with, Oliver. And Tony is extremely determined to shut out all the noise (from Oliver’s mouth) and just have sex. After the clumsiest sexual encounter ever, the two aren’t really sure what to do so they go to sleep.

The next morning, Max gets the text he’s been waiting for. Oliver wants to get back together! Max can’t dance out of Tony’s apartment fast enough. Until he sees a dog-sized monster in the hallway devour a frat bro. Time to reassess the morning’s activities.

Max races back inside Tony’s apartment, inadvertently allowing the monster-alien-thing in with him, and Max and Tony tag-team the cosmic creature, killing it through sheer luck. After realizing the city is under attack, they decide to team up and get to Hell’s Kitchen, where Tony’s brother and Max’s boyfriend, Oliver, live.

They instantly realize these aliens identify as ‘stranger danger,’ as they’re able to combine with each other and eat humans to turn into even bigger scarier aliens. Oh, and they also spit goo in your face, and if it gets in your eyes or mouth, you turn into an alien within the next ten minutes.

While Max wants to help everyone they meet along the way, the more selfish Tony just wants to get to their destination. After a particularly gruesome encounter, Tony finally reveals why he was so awkward in the bedroom. It’s that he only recently came out! More sympathetic to his reluctant teammate, Max starts to fall for him, which puts his and Oliver’s relationship in serious jeopardy.

Today’s script is maybe the hardest of all to read.

No, I don’t mean that in a negative way.

I actually mean it quite positively. The script is well-written. It moves fast. It’s got a nice fun vibe to it.

But the problem with the script is the real problem with most of the scripts in Hollywood. Whenever I tell anyone I’m a screenplay reader, the first thing they say is, “Oh, it must be so hard to read all those bad scripts.”

Well, no. The bad scripts aren’t the hard scripts to read at all. I actually enjoy reading bad scripts because nothing serves as a better reminder of what doesn’t work than a bad script. “On the nose” dialogue is a vague term that means nothing in a vacuum. But all it takes is reading one bad script with a ton of on the nose dialogue to remember exactly what on the nose dialogue looks like.

But scripts like Max and Tony’s Epic One Night Stand – they don’t do anything technically wrong. The script has two main characters, each with a strong goal. It has really high stakes. It has urgency galore. There’s the perfect amount of conflict between the two leads, which allows for a lot of chirpy comedic dialogue.

And that’s the problem. The script does exactly what it sets out to do and not an inch more. Which means it’s hard to identify why you don’t like it. Cause I didn’t really like the script. And I can’t really tell you why.

I suppose if you put a serrated knife to my throat and started mimicking a sawing motion, I’d start with the characters. Max kind of comes off as the stereotypical 90s gay character. He’s dramatic. He’s flamboyant. No matter what I did, I could not *not* think of Sean Hayes in Will & Grace.

And then with Tony, he didn’t have any personality at all. Now, in the writer’s defense, it turns out there’s a reason for that revealed later. Tony is hiding a lot about himself. But that doesn’t get you extra points. It’s more important for the audience to like the character than to be bored by the character but then get a really good reason for why they’re boring 80 pages into the script.

And since I’m so focused on dialogue these days, I’d make the argument that the dialogue here falls into that same category as the story execution. It’s never bad. But it quickly establishes a pattern – Tony tries to calm Max down, Max can’t help himself and continues to freak out – that it never deviates from.

If there’s a lesson to be learned about dialogue from this script, it might be that. If you keep doing the same-rhythmed joke over and over again, it starts to lose its power.

It’s a good reason to think long and hard about your characters before you write the script. Are they going to be able to deliver not just funny dialogue, but a VARIETY of dialogue, for 110 pages?

I felt like we needed one extra character who had a style of talking that was completely different from Tony and Max just to mix up the rhythm in places. With that said, there was one line that made me crack up. The ‘totally-in-denial-that-he’s-gay’ car service driver says: “You two are a real cute couple you know that? You remind me of this one gay dude I used to date and the other gay dude he left me for.”

I wished there were more clever lines like that. But most of it is just Max going crazy and saying something silly.

I did like the mythology of the aliens, though. I liked that they kept getting bigger and could mesh with each other. And essentially adding zombie rules along with it added another dimension. But the script could never overcome its expectedness. We always knew what was next. Maybe if the characters were sharper and more original, I wouldn’t have cared about the predictability as much. But since that was a problem, I definitely noticed it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A common issue I run into in these comedic team-up scripts is that the writer makes one half of the team the “funny character,” and then, in trying to make the second character the opposite, they just make him bland. And that was the issue with Tony. He was too bland. The “non-comedic” half of your two-hander still needs personality. The Other Guys is a good example of this. Mark Wahlberg plays the hot-tempered comic relief cop. But Will Ferrel is still hilarious as the ultimate rule-follower.

As I continue to work hard on finishing my dialogue book, I took note of one of the comments from last week which basically said the following: “When’s the last time somebody went to a movie for the dialogue?”

That question got me thinking. Because the truth is, I haven’t gone to see a movie for the dialogue since, probably, Juno. I remember hearing how great the dialogue was in that movie so I was excited to check it out.

But since then? Maybe the occasional Woody Allen or Tarantino movie had me intrigued about the dialogue. But I wouldn’t say that was the main reason I went to see those movies.

This had me wondering, do people even care about dialogue anymore? In the 90s, it was everything. During the indie boom, movies were graded heavily on their dialogue. But movies have changed radically since then. They’re more focused on thrilling you with a great space battle than impressing you with a clever turn-of-phrase.

Then reality slapped me in the face. Of course dialogue is important. It may not be the primary reason someone goes to the movies. It may not even be in the top 5 of their priority list. But I know this. Agents and producers are DESPERATE to find good dialogue writers.

Because they’re so freaking rare!

98% of working writers are able to fake their way through dialogue. By that, I mean, they know all the things you’re *not* supposed to do. So they can avoid those pitfalls and make their dialogue passable.

Only that tiny top 2% can write dialogue that sings. And, for that reason, those writers are very valuable. TV shows, which are more dependent on dialogue, are desperate to hire those writers. Producers constantly need to hire dialogue superheroes to do dialogue passes on their scripts. And those dialogue passes pay big money.

This doesn’t even begin to cover actors, who value great dialogue above everything. These are the lines they’re going to be saying so you bet your plucky pocketbook they’re choosing the scripts with the best dialogue.

That’s the thing you have to remember. The audience might not be showing up for the dialogue. But all the people who make movies? They’re looking for great dialogue writers.

Which is a long way of saying: Keep an eye out Mid-October for the Scriptshadow Dialogue Book! Oh, and I’m currently reading plays for the book. If you’ve got any suggestions for great modern plays, stuff written post-1990, please leave them in the comments.

Okay, moving on!

I’ve got two big things I’m looking forward to this week. On Wednesday, Andor comes out. And on Friday, Don’t Worry Darling comes out. Now a lot of you might be confused about my excitement for Don’t Worry Darling seeing as it’s got one of the “All Men Are Drowning in Toxic Masculinity” champions of the industry, Olivia Wilde, directing it. Which isn’t surprising since that’s basically what Don’t Worry Darling is about.

But there’s a lot more going on with this movie than just that. It’s a spec script. And I always root for spec scripts. Not just a spec script writer-director. But a spec script that writers wrote, somebody purchased, and then another director made. I love when that happens. It gives me hope that, if the movie does well, it will start a spec resurgence.

It’s got a sci-fi slant, which you know I love. And I particularly love when writers mix subject matter that normally would have nothing to do with sci-fi. The last thing you would expect in a 50s suburban neighborhood drama is a sci-fi twist.

I think the cinematography and vision of this movie look amazing. That shot in the trailer where Florence Pugh is being squished up against the wall by an invisible shield hints at a really creative mythology that I’m totally down for.

And then you’ve got one of the best up-and-coming actresses in the world in the lead role with Florence Pugh. I think she’s amazing. So I want to see what she’s going to do in the role. I also think it’s funny that she hates Olivia Wilde. The movie is about feminism and the two main female talents on the project hate each other. Come on, you have to love the irony.

Anyway, I’m going to be reviewing the movie next Monday. So BUCKLE UP.

Since we’re talking about feminism, let me take a quick detour before we cover Andor. The Woman King not only took in a surprising 19 million dollars this weekend, it got an A+ Cinemascore! Holy coyotes. I used to think that cinemascores were worthless but it turns out they’re the best indicator of how well a movie will do over time at the box office.

The movies with the highest scores have the lowest financial declines week-to-week. Case in point, the number one movie of the year, Top Gun Maverick, had an A+ Cinemascore. Meanwhile, Jordan Peele’s “Nope,” which did lousy in the weeks after its opening, received a B Cinemascore.

I’ll probably wait for this one to come out on streaming before I watch it. I’m having a bit of a suspension of disbelief issue with Viola Davis as an action hero. I mean, what’s next? Paul Giammati as Alexander the Great? Michael Cera as Hercules? Still, we always complain in the movie business that they don’t make anything different anymore. This movie is definitely different. So I’m glad that they found success in a market that isn’t always accepting of new ideas.

Okay, moving on to Andor. We’re just three days away from the Star Wars series that NOBODY thought would happen. This comes on the heels of Lucasfilm officially shoving a thermal detonator into the gullet of Rogue Squadron, which has been jettisoned from the Star Wars line-up, made to rot in perdition along with Rian Johnson’s future trilogy that was going to have every single person in the universe be a Jedi. The tagline, I hear, was: “We’re all special!”

The first reactions from Andor seem to confirm what everyone already assumed, which is that it’s a super serious version of Star Wars. The issue with social media reactions is the same issue that’s happening with these “7 Minute Standing Ovation” stories from film festivals. Once you establish that every single movie is getting one, it doesn’t mean anything anymore.

Those social media reactions claiming that every new Marvel release was the best Marvel film yet numbed all of us to them. Even worse, if your movie DIDN’T have “this was the greatest thing ever” reactions, and only had, “Yeah, it was pretty good” reactions, we knew the film was hogwash in a hand basket.

Andor is coming in with very tepid praise. “Yeah, it’s different from every other Star Wars,” people are saying. Okay, but nobody cares about that. They just care if it’s good. I still think it was an enormous gamble to build a show around a character who didn’t even pop in the original movie he was in. Rogue One made most of its money based on the fact that the average moviegoer thought it was a sequel to The Force Awakens. It didn’t make a bunch of money because it was a good movie. Arguably, it didn’t have a single stand-out character in it.

I’ll pose the question to you guys. Name me, in order, your top 3 characters from Rogue One. I’m guessing that K2SO, the big droid, comes out as number 1. And he was just some side character. He didn’t even have a big role.

The only thing that gives me hope here is Peacemaker. Peacemaker was lame in The Suicide Squad. But his show was absolutely awesome. Maybe once we get Cassian Andor away from the big plot in Rogue One, and let him breathe a little, he becomes a far more interesting character. I sure hope so. Because they’re giving us 12 episodes of this thing. The biggest Star Wars show by far. If it’s great, I’m going to be doing jumping jacks in roller skates.

I’ll review that either at the end of the week or next Tuesday.

In the meantime, I’ll be watching my current favorite show, House of the Dragon. This show is exceptional. I’m completely bought in. I’m a little nervous about the impending time jump and getting rid of Young Rahenyra. But I have so much faith in the writers, at this point, that I’m giving them the benefit of the doubt.

This review was originally in a newsletter but with the recent release of the trailer, I decided to officially put it up on the site. Enjoy!

Genre: Period/Hollywood

Premise: Follows a young Mexican man in the 1920s who has aspirations of working in Hollywood. But when he falls in love with a crazed rising star, his life becomes one giant whirlwind.

About: Babylon will be Paramount’s big Oscar entry in 2022. Originally meant to bring Damien Chazelle and his La La Land actress, Emma Stone, back together, Covid reset the scheduling chess pieces so that Stone was forced to leave the project. Luckily, Chazelle appears to have upgraded the role, with Margot Robbie taking over. Robbie will re-team with her Once Upon A Time In Hollywood co-star, Brad Pitt, which seems apropos considering this is another movie about old Hollywood. Chazelle wrote and is directing the film.

Writer: Damien Chazelle.

Details: One hundred and eighty-four f@#%ing pages no I’m not lying.

I always have to be careful with Damian Chazelle because I’m not his biggest fan, yet I understand that a lot of people love his stuff.

But, I mean, come on. This is some of the most self-masturbatory writing I’ve witnessed in a decade of reading scripts. Damian Chazelle wrote this movie for one person and one person only – himself. And probably while he was on a lot of drugs. Cause there is nothing about this story that… well… works. It feels like the equivalent of a madman ranting on the corner of Melrose and La Brea for three hours.

Manny Tores is 21 years old with dreams of working in the entertainment business. He’s somehow managed to secure an assistant job with Hollywood bigwig, Don Brady. Don is throwing a party tonight and he wants it to be memorable. Which is why he’s asked Manny to secure him an elephant.

It turns out that securing an elephant for a Hollywood party in 1926 (when our movie is set), isn’t easy. There aren’t a lot of trucks that can transport an elephant. But there is no way Manny is showing up at this party without the one thing he’s been hired to secure. So Manny convinces a driver to tear off the roof off his truck in order to transport the elephant.

Don Brady’s party is crazy. Within ten minutes, an obese man accidentally kills a hooker who he’s hired to pee on him (yes, it is that kind of movie). Meanwhile, Manny’s hanging out in the back yard when a car bursts through the bushes and crashes into the fountain. Over-confident nobody and self proclaimed mega-actress Clara Bow, who’s never had an acting role in her life, asks who put this stupid fountain here then waltzes into the party like it’s the most normal thing in the world.

Clara is LOUD and BOISTEROUS and says things like, “You know you’re not bad looking,” and then, a second later, “Take your clothes off.” Which is how Manny has sex with Clara less than ten minutes after meeting her. For Manny, it’s love at first sight. For Clara, it’s one more bang in a long line of hankey-pankeying. Besides, she’s got more important things to do, like impress Jack Conrad (Brad Pitt), the biggest movie star in the world. Gotta mingle if she’s going to execute her plan of being the greatest actress ever.

By the way, in 1926, movies are silent. So you didn’t have to be some amazing actor. You just had to look like a star on screen. Using the party as a springboard for her first role, Clara shows up on set the next day and convinces the director to upgrade her tiny role to a bigger role and, what do you know, she nails it! When the movie comes out, Clara is officially the new hot thing.

As 1926 becomes 1927 and, eventually, 1928, the slow transition to FILM SOUND begins. You would think this would have a major effect on the plot but Chazelle isn’t a good enough writer to pull that off. So it becomes this back seat annoyance that occasionally pops its head up to the front. Clara has to learn how to read lines since her voice will be heard. Jack Conrad doesn’t like “talkies” which leads him to trying out Broadway for some reason.

Through 1929 and 1930, Manny works his way up to being a studio exec. A studio exec with a bad drug problem. Clara had a drug problem. Now Manny has a drug problem. Sure, no repetition in character development there at all. SARCASM! Manny hires Clara for roles as much as he can so he can be around her. But Clara has lost it by this point. She was a trainwreck as a nobody. As a big star, she’s a trainwreck supernova. Her big vice is gambling. When things aren’t going well for her, she drives off to Vegas and gambles.

During a particularly bad day on set, Clara does just that, leaving the production without telling anybody and playing blackjack all night at a casino. She loses 83 thousand dollars that she doesn’t have. Manny, who still loves Clara, informs the casino that he’ll take the IOU. But when Manny can’t pay the money, the bad guys come after him *and* Clara.

Manny tells Clara they have to flee to Mexico. A drugged out Clara half-agrees and off they go. But the bad guys catch up and Manny is faced with a choice. Try to save Clara one last time or get the hell out of here. He chooses to get the hell out of here, leaving Clara to the sharks. Her fate will remain unknown. Twenty-five years later, Manny comes back to Hollywood and decides to watch a movie. It’s Singing in the Rain. He cries. Fin.

I have no idea what I just read.

I guess the one good thing you can say about Babylon is it’s better than Mank. Mank was rambling and dreary. At least this is rambling and crazy. It has an energy to it. But you guys know my screenwriting philosophy at this point. Simple story, complex characters. This is not that. This is a complex story with too many characters and not enough connective tissue to bring it all together. It may sound like there was a story here by my summary. But that’s only because I moved literary mountains to write a summary that made sense.

Here’s the problem. Chazelle loves this era. In the same way that Fincher loved Citizen Kane. And when artists love something this much, they want to include everything. Storytelling is the opposite of that. It’s eliminating information that gets in the way of the story you’re trying to tell.

There’s this scene in Babylon where Clara gets really drunk at a party and decides she wants to fight a rattlesnake. She keeps yelling and screaming until someone finds her a rattlesnake, she fights it, and it bites her. This leads to a Pulp Fiction ripoff scene where they have to hurry Clara to the hospital to get her the anti-venom so she’ll survive the snake bite.

In a vacuum, you can argue it’s a fun scene. But in a movie that’s constantly zig-zagging around without purpose, it’s one more scene that takes us further away from a comprehensible storyline. Ditto spending 10 pages of your movie following an unnamed “Obese Man” with a pee-fetish who accidentally kills a hooker. How does this push the story forward at all? It’s one more wild and wacky moment in a movie full of wild and wacky moments.

During this read, I was constantly thinking about Once Upon A Time in Hollywood. There are a lot of similarities between the two. They both explore one of Hollywood’s golden ages. They both explore the weirdness and insanity of the movie business. They both endear themselves to the wily characters you find in this industry. Yet one felt utterly assured of itself while the other felt desperate and untethered.

One of the early jokes in Babylon is that this elephant Manny picks up keeps pooping. There are so many references to this elephant pooping, you’d think we were watching Horton Hears a Poo. Then, when Manny gets to the party, he’s told by Don Brady’s second-in-charge to deal with the crazy gossip columnist downstairs who’s lost her dog. So Manny locates her, she screams that her dog is missing. Manny finds the dog a few minutes later, only for the dog to take a poo on the couch.

That’s two animal pooping jokes within the first 20 minutes of your movie. I just thought, “Would Quentin Tarantino ever stoop to animal pooping jokes?” Of course he wouldn’t. Animal pooping jokes are the classic signs of a desperate writer. A writer who doesn’t have the confidence that they can keep your attention without something crazy and wily going on. A fat studio exec has to get pissed on. An elephant needs to be pooping. The lead female character needs to blurt out things, apropos of nothing, like “Should I shave my pu$$y?” That’s the writing talent on display here. I still don’t understand how this guy has become successful.

If he was a halfway decent writer, he would’ve realized he had a clear story to tell. You focus on a famous actor or actress in the silent film era who must make the transition to “talkies.” The obstacle is they have a weak voice. This happened to a lot of silent movie actors when sound came around. They didn’t sound like the audience thought they did and their careers nosedived. Just tell the story of one of those people.

Instead, we get this desperate hackneyed unfocused blitzkrieg through Hollywood in the 20s. I mean…. Hollywood loves them some movies about old Hollywood. And with Robie and Pitt, I’m sure this will look great. But I’ll eat my boxers if they’re able to salvage anything good out of this script. It’s complete and utter nonsense.

[x] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I Learned: There is no script you need extra eyes on more than your passion project. Artists have ZERO objectivity when it comes to their passion projects. They want to include everything. But like I said earlier, you can’t do it. You have to identify what your script is actually about and strip away everything else. I contend this is a movie about an actress who is great in silent films but doesn’t have the voice for when the industry transitions to talkies. If Chazelle would’ve realized that, he wouldn’t have a wandering 180 page script. He’d know exactly what needed to be cut. So when you’re writing about something you love dearly, get an extra set of eyes on it and ask those eyes what they think your script is really about. Once you get that answer, start cutting out everything else.

GET A SCRIPTSHADOW SCREENPLAY CONSULTATION! – As much as we writers think we can do it alone, we need help. We need fresh eyes on our material. Without that, we can’t identify the problems in our scripts. We won’t figure out where we need to improve as a screenwriter. I’ve read over 10,000 scripts. Done over 1000 consultations. I am the guy who can figure out the issues hampering your script AND HELP YOU FIX THEM! I have a 4 page notes package or a more detailed 8 page option designed to exponentially improve your screenplays. I also give feedback on loglines (just $25!), outlines, synopses, first acts, or any aspect of screenwriting you need help with. This includes Zoom calls discussing anything from talking through your script to getting advice on how to break into the industry. If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s set something up!

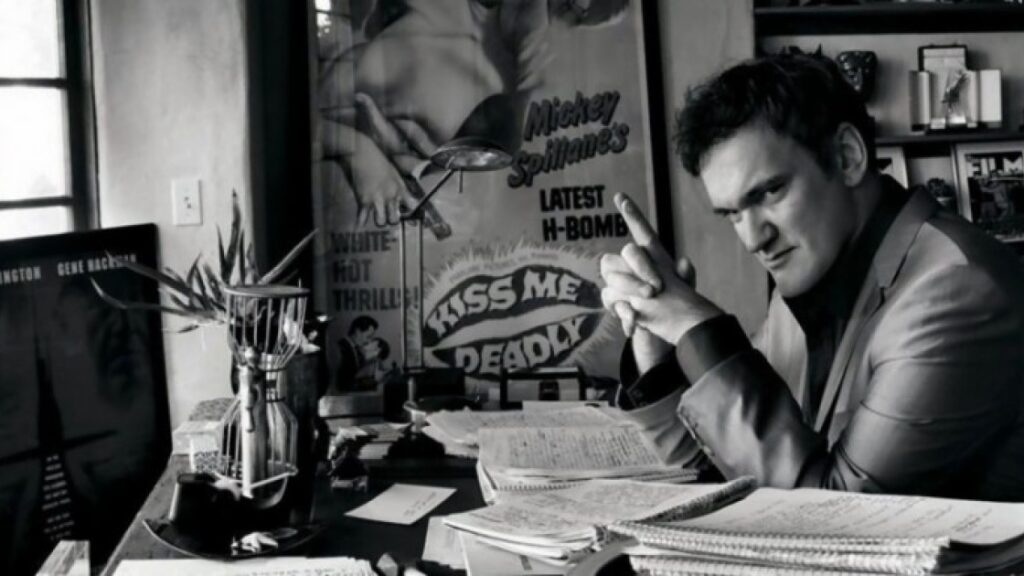

Write dialogue like this guy!

Write dialogue like this guy!

The bulk of the Scriptshadow Dialogue book is written. The one chapter I’m still working on is this chapter I’m tentatively titling, the “verbal arena.” This is the chapter that’s going to teach you how to write like Tarantino, Woody Allen, Diablo Cody, Aaron Sorkin. I know some of you will scoff at this but that’s my goal. Sure, I can’t make you as good as those writers. But I can give you the tools to get a lot closer to them than you are now.

So, I’ve been watching a lot of “verbal arena” movies – flicks where the dialogue is inventive and fun and memorable – trying to decode that unique dialogue Matrix within. The other night, I watched Barry Levinson’s, “Diner,” which I hadn’t seen in 20 years and didn’t remember well. But I’ve heard a lot of people talk that movie up as an example of great dialogue.

Man, I have to say, I was really disappointed. Outside a couple of minor exceptions (“Where’d you get this attitude?” “Borrowed it. I’ll have it back by midnight.”) it was mostly mundane middle-of-the-road conversation. I *was* shocked when I realized just how much Swingers borrowed from the film. But, other than that, it was an average movie with, maybe, slightly-better-than-average dialogue.

At that point I was going to go to sleep but then I remembered a script whose dialogue had always impressed me and decided to bust it open and read a few pages to see if I still felt the same way. The script is called “Daddio.” It was a high ranking Black List script from five years ago.

Let me tell you: I’ve been reading A LOT of dialogue over the past few weeks — from amateur scripts, to pro scripts, to pantheon level classic movie scripts — I’m not exaggerating when I say the dialogue in the first ten pages of this script blows almost all of those scripts away.

So much so that I’m going to spend the next few days ONLY diving into this script and trying to figure out what Christy Hall is doing that makes her dialogue so good.

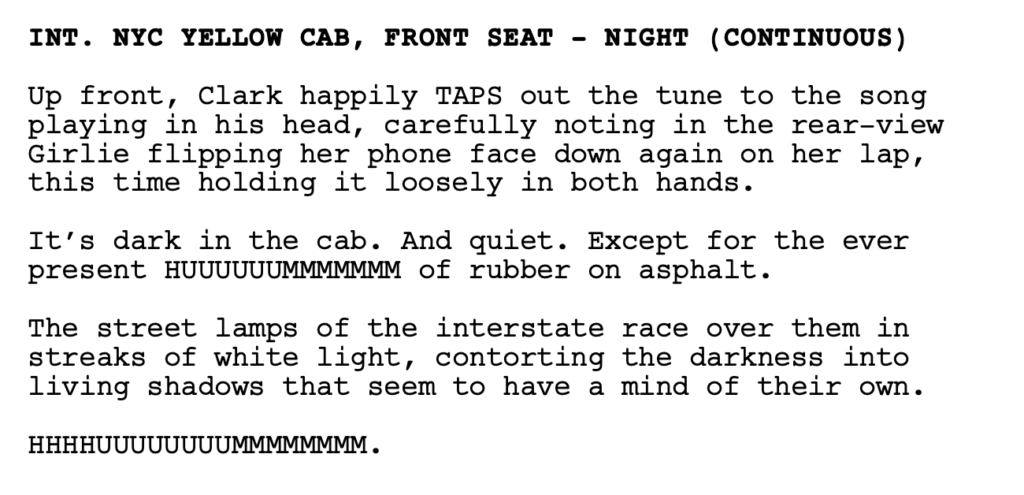

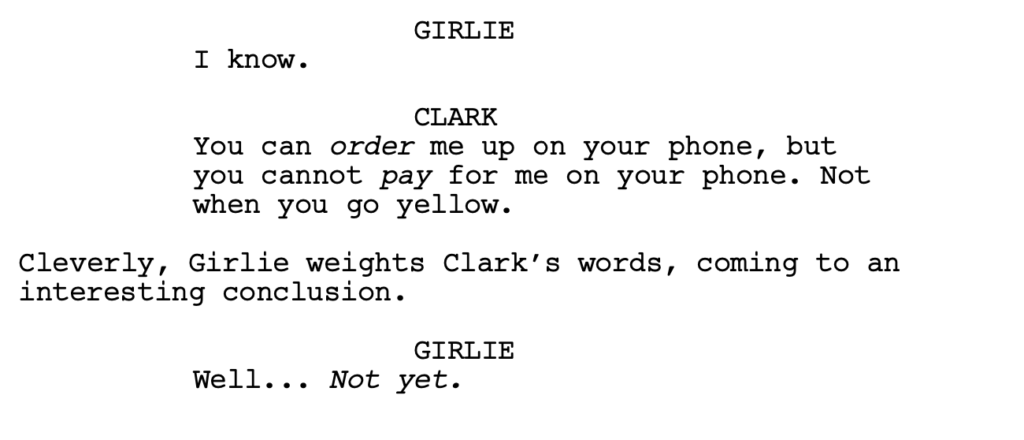

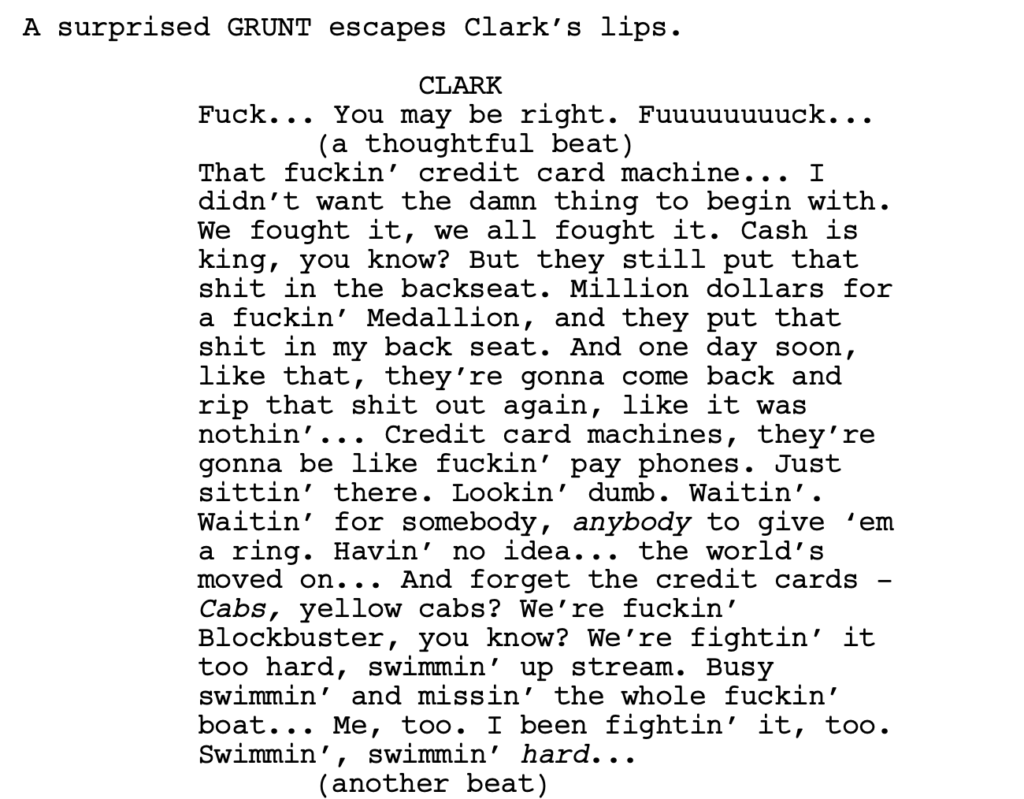

Now, the scene that I’m about to show you is a little different in that it’s more a monologue than a dialogue. But it’s so good I think it’s worth highlighting. In the scene, our main character, Girlie, has just landed at JFK airport, and is going to meet a guy who, from the limited text messages we’ve seen between the two, doesn’t seem all that into her, which is something she’s trying not to think about too much.

The cabbie guy becomes a temporary distraction from this potential down-the-road problem. The script takes place entirely in the cab as we ride from JFK to this guy’s place. It’s one long conversation. What we’re seeing here is the beginning of the conversation.

The first thing you want to pay attention to here is the organic nature of the conversation. This isn’t a “normal” scenario. For example, this isn’t two people waiting at a valet stand for the valet to pull their car up. It’s a long cab ride. There’s a lot of down time involved. Conversations are different in down time. They’re not as immediate or necessary. People are more likely to ramble, which is why this scene works, whereas, if it were at the valet stand, a long philosophical rant about rideshare apps taking over the world would feel try-hard.

My point is, know the situation in order to know what kind of dialogue you can use. The rambling nature of this dialogue works because it’s organic to the situation.

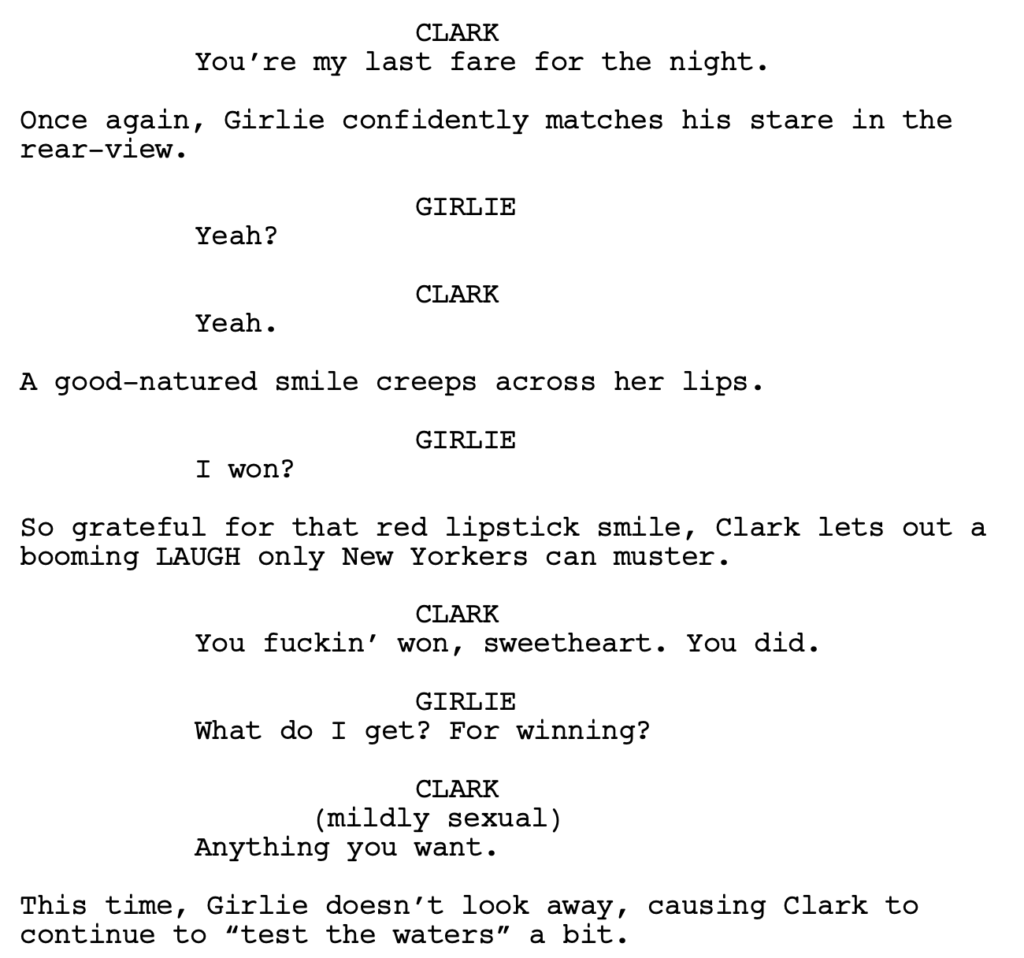

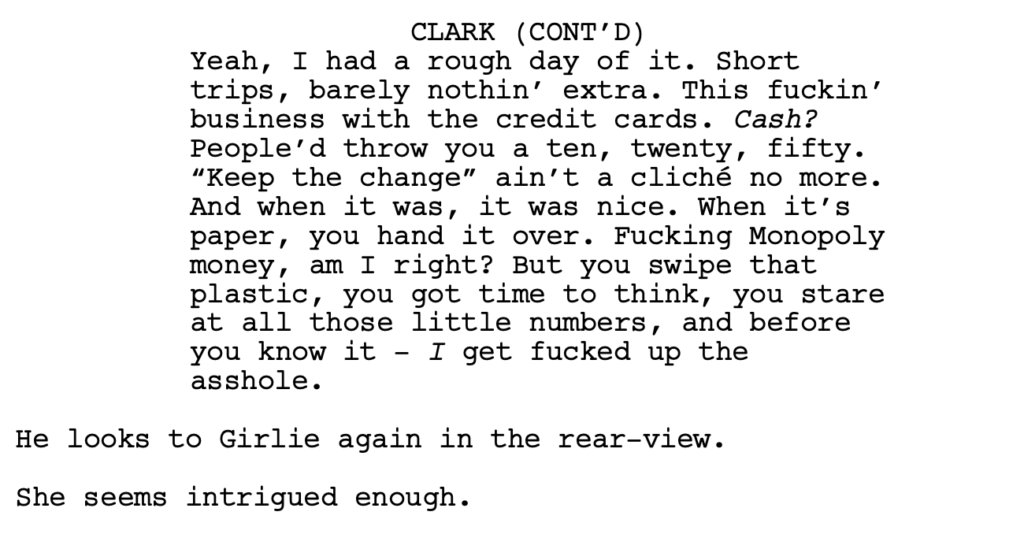

The first segment of Clark’s dialogue is the most “normal.” It’s a guy talking about how his day sucked, he didn’t get a lot of good fares, and he’s unhappy about this payment switch to credit cards cause he makes less money on it. Most writers could write this segment. Although, I thought the “Monopoly money” choice was thoughtful. More creative than saying, “Cash.” Look for these little opportunities to replace standard words with something more imaginative.

The second segment, however, is where Hall starts to take off. She’s in a triple-7 and everyone else is putt-putting around in a Mini Cooper. Quite frankly, it makes me jealous. Usually, when I read dialogue, I can break down what the writer is thinking and how they crafted the scene to make the dialogue work. But here, there’s so much going on, it’s impossible to keep up.

I like the exaggeration and specificity after the mention of the word “app.” It isn’t just, “These f#$%ing apps are making my life miserable.” It’s, “And now, these f@#%in’ apps, all of ‘em – can get a cab, a coffee, burger, soap, socks, wine, water, Chinese f@#%in’ take out – you can get all that s@#t, and not even reach for your purse, not once, not even for tip.”

Reeling off a number of items drives home the reach of this emerging “app world” Clark hates so much.

From there, the monologue accelerates even more. I’m noticing that in “verbal arena” writing, writers use a lot of metaphors. A metaphor takes an object or action and compares it to something familiar but unrelated. “Charles was a fish out of water.” “Love is a battlefield.” “Life is like a box of chocolates.”

Good writers don’t just use quick familiar metaphors. They take those metaphors and play with them. They extend them (which is why this device is known as an “extended metaphor”). That’s a big part of what’s going on in this scene. Our cabbie character is obsessed with this idea of “the cloud,” and how everything goes up into the cloud. But instead of solely treating the cloud as the technical thing that it is, in this case, it’s used as a metaphor for a real cloud. And what happens when real clouds get full? They start raining.

Hall also intermittently uses something called “personification.” This is when you take a non-human object and you give it human traits. “That big f@#%in’ cloud, thinkin’ it knows better. Swearin’ it can keep a secret.” Then later: “they’re gonna be like f@#%in’ pay phones. Just sittin’ there. Lookin’ dumb. Waitin’. Waitin’ for somebody, anybody to give ‘em a ring. Havin’ no idea… the world’s moved on.”

Another device Hall uses is something I call the “history lesson.” It’s when a character will bust out some historical story or fact that teaches the reader a little something and adds variety to the monologue. We’re in the present and then – BAM – we’re in the far-off past.

“I mean… Salt used to be money. Mother fuckin’ salt. The same shit you sprinkle on your eggs. Yeah. Every mornin’ you toss that cheap-ass-shit all over your eggs with no idea that people used to die for it. Tea, coffee, same thing. All that shit you gloss over at the grocery store, at one point in time, humans fuckin’ killed each other for it.”

This moment in the monologue is important to highlight because I don’t think 99% of writers would’ve written it. Why go off on that tangent when you can be more succinct? But that’s who this character is. He’s a tangent guy. So you want him to go off on a lot of tangents.

Hall then writes my favorite line in the monologue: “Little numbers on a screen. You can’t touch it or hide it or bury it. Nah, you just tie it to a fuckin’ butterfly and send it to that cloud up there.” I have no idea what the device is here or how Hall came up with this line. It seems to be pure imagination, the writer’s own creativity. She could’ve easily written, “You can’t touch it or hide it. It’s just up there in the cloud, hovering.” Not nearly as imaginative.

I like how she also uses adjectives to spruce up, otherwise, bland objects: “But, one of these days, I’m tellin’ ya, that cloud’s gonna open up and it’s gonna pour acid rain down… all over our dumb faces.” It’s not “rain.” “Rain” is way too bland. It’s “acid” rain. It’s not “our faces.” “Our faces” doesn’t tell us much. No, it’s our “dumb” faces.

At every opportunity, Hall is looking to turboboost her sentences. She’s using every pixel to weaponize these words so that they have impact.

From there, she continues to use metaphors to make the dialogue more interesting. “We’re f@#%in’ Blockbuster, you know?” And, “We’re fightin’ it too hard, swimmin’ up stream. Busy swimmin’ and missin’ the whole f@#%in’ boat… Me, too. I been fightin’ it, too. Swimmin’, swimmin’ hard…”

The biggest lesson to take away from today’s dialogue example is metaphors. A lot of the color from this dialogue comes from Hall repeatedly dipping into metaphors. Yes, there’s more going on. But if you try to ingest it all, I’m afraid it will be too much. Just start to look for ways to incorporate more metaphors into your dialogue. Make sure you’re doing so in an organic way. And try to play with them a little bit so they’re not cliched metaphors. You don’t want to say things like, “Flying off the handle” or she has a “heart of gold.” These are actually referred to as “dead metaphors” because they’ve become so overused. Try to come up with your own metaphors and then extend (play with) them.

Here’s the screenplay for Daddio if you want to see more of Christy Hall’s writing. Leave your thoughts about what else she’s doing right in the comments. And, if you disliked the dialogue, tell us why.

GET A SCRIPTSHADOW SCREENPLAY CONSULTATION! – As much as we writers think we can do it alone, we need help. We need fresh eyes on our material. Without that, we can’t identify the problems in our scripts. We won’t figure out where we need to improve as a screenwriter. I’ve read over 10,000 scripts. Done over 1000 consultations. I am the guy who can figure out the issues hampering your script AND HELP YOU FIX THEM! I have a 4 page notes package or a more detailed 8 page option designed to exponentially improve your screenplays. I also give feedback on loglines (just $25!), outlines, synopses, first acts, or any aspect of screenwriting you need help with. This includes Zoom calls discussing anything from talking through your script to getting advice on how to break into the industry. If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s set something up!