You guys have been waiting for it!

Maybe “waiting for it” is an understatement. “Angrily demanding it” might be a better assessment?

I do apologize for taking so long but this is one of the realities of a free script contest where one reader reads all the entries. It’s going to take a while.

Reading screenplays is a funny thing. I personally love doing it. People ask me all the time, “How are you able to get through all those bad screenplays? Doesn’t it drive you nuts?”

It doesn’t, actually.

For a couple of reasons. One, I love storytelling. I get a kick out of characters trying to maneuver their way through obstacles to achieve an objective. I have this inherent need to “see what happens next.” Even if it’s not perfect, I like being in an imaginary world and not knowing what to expect. It’s exciting.

Second, there’s a voyeuristic aspect about writing that I love. Every time you read a script, you’re essentially going into someone’s head. They’re bringing you into their universe in a way that you don’t get in any other medium.

You learn about a person’s fears in a way they’ve never told anyone else before. You get to see their bizarre interpretation of the world. And you get reminded that we’re all experiencing the same things together. Like when a character has doubts, it’s a reminder to you that having doubts is okay. Writing connects you with the rest of humanity.

That’s not to say it isn’t frustrating at times. Yesterday’s script was a reminder of how vapid and vanilla many scripts can be. Writers choose ideas that are way too common then execute them in the most obvious fashion possible. That’s the part of writing I don’t like. When writers don’t give you anything new.

I’ve often asked myself why does this happen? Cause to me, it’s obvious that they’re giving us an old concept with a predictable execution. So why isn’t it obvious to them?

The conclusion I’ve come to is that for a very long time in every screenwriter’s journey, they’re trying to rewrite their favorite movies. They have 3-10 movies they loved growing up. And they’re basically writing and rewriting identical versions of those movies. They don’t realize they’re doing this because, as they’re writing, they feel inspired. And who’s going to say no to inspiration? What they’re not identifying is that their inspiration is coming from a place of replication, of getting to recreate something they love.

I’m not sure you ever truly grow out of this phase. But good writers reach a point where they understand that they’re doing this and take precautions to differentiate their scripts from their favorite movies. They find ways to tweak the concept, tweak the genre, tweak the execution, so that while their script may be inspired by that favorite film of theirs, it becomes its own thing.

Get Out is a great example of this. Jordan Peele clearly loved Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner as a kid. He then tweaked the genre to horror and, all of a sudden, you’ve got a completely different movie.

So that’s what I’m looking for whenever I open a script – writers who’ve gone through this maturation process and realize writing a vanilla execution of a familiar concept isn’t good enough. They have to find a new way to tweak things or not write the script in the first place.

So has this latest contest taught me anything new?

Not really.

But it has reinforced a few things. Reading a bunch of scripts in a row reinforces, to me, the importance of nailing that first scene. If the first scene isn’t entertaining – if it’s just setting up a character’s life or setting up the world – you’re done. Because the script that reader read right before yours? That one DID entertain them right away. So why would they pick your script over that one?

It also reinforced the cut throat nature of screenwriting. You realize that the person who writes the script doesn’t matter. I know that sounds harsh but I don’t sit here thinking, “Man, this writer has probably been through so much to get to this point where they’re able to write a competent screenplay and they’re really hoping this script is going to be the one that finally breaks down doors for them and I have to respect their work ethic and how hard it was to get to this point and…”.

No!

The ONLY thing that matters is “Am I entertained?” That is it, man. That is f@#%ing it.

I’m telling you. When you read 15 entries in a row, you aren’t thinking about the writer. You’re thinking, “is what’s on the page entertaining me right now?” Better yet, you’re not thinking at all because you’re enjoying what you’re reading so much.

I know this sounds harsh but I say it because I believe it can help you. Once you realize nobody cares about you, you can take yourself out of the equation and simply ask, “Is the reader going to be entertained by this scene I’m writing right now?”

The second – and I mean THE SECOND – you write a scene that could be considered boring in the first 15 pages, you have likely lost the reader.

Enough generalizing, Carson. Give us an example! Okay, so I read a WW2 entry the other day. This is World War 2, mind you. One of the most deadly dramatic intense wars in history. Every human being who was in World War 2 in any capacity has at least one INSANE story about something that happened to them.

I read a World War 2 contest entry where, for the first ten pages, characters are talking to each other and doing chores. I’m sitting there staring at these pages thinking, “What’s even happening right now???” How are you writing about World War 2 and use your first 10 pages as character setup????????????? This is such an immense miscalculation, I can’t even comprehend it.

Conversely, I just reviewed Randall Wallace’s World War 2 script, With Wings as Eagles, and the opening scene has a secret black ops German soldier stumbling into a room full of Russian soldiers and having to find a way out of it.

By the way – I want to make this VERY CLEAR – me needing an entertaining scene does not mean a big splashy action scene. Look at Inglorious Basterds. The opening scene with Hans Landa looking for Jews – not a big flashy scene at all. But one of the most entertaining scenes ever written.

This is what you’re competing with people.

Think of the screenwriting world as an entertainment contest. You are going head to head with people who are trying to write way more entertaining scenes than you. So ask yourself, as you’re writing that first, that second, that third, fourth, and fifth scene, “If these scenes were to go up against 100 other screenplays, do I honestly believe that each of my scenes would beat 97 to 98 of the other scenes on an entertainment level?” Cause if not, you’re not doing this right.

You gotta be the top 1 or 2 out of 100 to make any waves in this business.

This brings me to a secondary issue that I’ve been seeing in many of the entries, which is that the writer WILL BE TRYING to entertain with their first scene. But they’ll do so in too familiar of a way. Kudos to the writer for at least understanding that you have to pull the reader in. However, an entertaining scene we’ve already seen before is still a script killer. True, there are only so many entertaining scenarios to choose from. But there are an infinite number of ways to execute a familiar scenario. And your job, as a screenwriter, is to find one of those angles.

For example, I’ve read a handful of entries so far that start with a female character running from something. Three of those entries happened in the woods. How common is an opening scene of a woman running from something in the woods? Very common. And the writers didn’t do anything different enough with the scenes to pull me in.

What does “different enough” look like? “It Follows.” That movie starts with a woman running. But they’re running in odd circles in the middle of an empty suburban street. They’re looking behind them as if something is following them but we’re seeing nothing. What’s going on here? Why is this woman running from nothing?? That’s a familiar opening that adds a fresh element. I want to know more after reading that. I don’t want to know more after reading a frantic woman in the woods running from a killer. I’ve seen that way too many times already.

Okay, Carson, now that you’ve depressed us to the point of wanting to burn our pirated copies of Final Draft, do you have any good news for us? Any scripts that have actually impressed you? Yes, in fact. Let me share with you the two latest scripts to advance to the next round.

One is a sci-fi script called, The Castle. Here’s the logline: In 1209 a reluctant German crown princess must defend her castle against a brutal group of bandits, consisting of special forces soldiers from the 21st century. Script starts off with a cow-hanging that got my attention. I love seeing fun concepts and then I open the script and get something completely different from what I expected. A cow-hanging??? It was great. And all the characters are really fun so far.

Another is a psychological thriller called Smiley Face. That one is about a popular online influencer’s troll. Admittedly, I’m fascinated by influencer culture. So this one got points just for being the type of idea I’m into at the moment. But I felt that the writer did a good job conveying what an influencer’s life was like and, also, what an influencer’s troll’s life was like. It’s just as demanding of a job as being the influencer. So that one feels promising.

How long is it going to take me to finish all these? I don’t know. Sometimes I read 100 entries a week. Sometimes I read 10. It depends on my mood and my workload. But I’m going to try to incentivize myself to keep charging forward.

Next week I am going to highlight ten entries on the site. I am going to list the script details you sent me, as well as letting you know if your script advanced to the next round or not. Then, I’ll include several hundred words on why I either advanced the script or passed on it. If you want to be one of these ten, e-mail me at carsonreeves3@gmail.com and the first ten of you who e-mail, you will be the ones who get your script highlighted. Bonus points if you allow me to post a PDF of your first act.

To be clear, I’m not going to trash your script if I don’t advance it. This is going to be more of a teaching thing. I want to help you, and others, understand what’s required to write a strong first act.

If you’re game, let me know!

ONE “$100 OFF” SCRIPT CONSULTATION DEAL! – It’s mid-month so I’m giving $100 off one feature (feature only!) screenplay consultation. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with subject line: “100.” I give screenwriting consultations for every step of the process, whether it be loglines, e-mail queries, plot summaries, outlines, Zoom brainstorming sessions, first pages, first acts, pilots, features. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested in today’s deal or any other type of consultation. I’ll be here!

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: When stranded on the far end of Manhattan by a mysterious city-wide blackout, a group of inner-city middle schoolers must fight through seemingly supernatural forces to make their way back to their parents in the Bronx.

About: Today’s writer, Chad Handley, did a little TV writing, mostly story editing, on The Righteous Gemstones. This script finished with 7 votes on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Chad Handley

Details: 125 pages (!!)

Seems like Caleb McLaughlin would be a slam dunk choice for the lead here.

Seems like Caleb McLaughlin would be a slam dunk choice for the lead here.

Whenever I see a Black List script at 120+ pages from a writer not named Aaron Sorkin, I get worried. But, as we’re going to talk about today, page length isn’t as important as “page quality.”

“Page quality” is the concept of making sure your pages are entertaining. If you do that, it does not matter how many pages your script is. The irony is that writers who write over 120 pages tend to be the writers who believe that anything they write is must-see screenwriting. They don’t have that inner editor who’s able to say, “This doesn’t move the story forward,” or “This isn’t entertaining enough to warrant its inclusion.” So their 120+ scripts perpetuate the rule that all long screenplays are bad, as opposed to change the narrative.

We saw this just this weekend with Thor Love and Thunder. Taika had a 4 hour cut. He realized that two of those hours were neither relevant or entertaining enough. So he cut them out.

Okay, onto the plot!

For what it’s worth, I believe everyone in this story is a minority. David Wei is the CEO of a giant mysterious particle physics company and he’s built this thing called the “Inflation Reactor,” which sounds like something that’s responsible for my recent 90 dollar trip to the gas station.

Let’s meet our kids. There’s 15 year old Amir, who’s always stealing things. There’s his twin sister, Seneca, who also likes to get into trouble. They have their little brother, Isaac, who’s obsessed with science. Then have a dad, Seth, who’s never around.

We also have Kale, Amir’s football player best friend, and other friend Chance, who’s a loudmouth. We’ve got Parker, a hot rich girl Amir is in love with. And then Lily, Parker’s 8 year old sister.

The group all meet at the Science Museum because Isaac has to study something there for a school assignment. Then, on their way home on the subway, there’s an explosion, and they have to climb out of the wreckage and get back to the surface. Along the way, they lose their father, which, if we’re being honest, isn’t that different from their everyday life.

After stumbling around the city looking for him, they learn of these alien beings who have made it to earth through that Gas Hike machine David Wei built. These beings have stopped the planet from spinning and also stop random people in time and space, so random New Yorkers will be straight up frozen. Will our Goonies-esque team find their dad? And what about destroying these alien creatures? Can they use science to send them home? We’ll find out.

One of the most difficult things to explain in regards to “good screenwriting” is this concept of looseness. One of the biggest differences between really good screenwriters and really green screenwriters is that the good screenwriters have a tightness to their writing.

They can set up a character in just three lines who feels like you’ve known him your whole life. Then can craft a single scene that sets up a character, moves the plot forward, and is highly entertaining in under 2 pages. And their ability to pace the story so that it never feels slow is second nature.

Whereas, green screenwriters sort of ramble on unnecessarily. Scenes don’t alway have a purpose. They’ll take four scenes to set up a group of characters they could’ve set up in two. There’s a lackadaisical approach to exposition so that it takes way too many scenes to get relevant information across.

That’s the feeling I got while reading The Dark. The first 30 pages were SET-UP CENTRAL. Setting up characters. Setting up mythology. Setting up family relationships. Setting up birthdays. Setting up homework that’s due. Setting up friendships.

And I know that you have to set stuff up somewhere. It’s not like you can just skip all this. But this is where the good screenwriters prove their worth. They can move faster through this stuff. And they make it a lot more entertaining.

Which, by the way, is a secret way to speed up a story. Two screenwriters can be tasked with writing the same scene. Both scenes are exactly the same length – 4 pages. But, somehow, one feels WAAAAAAY faster than the other.

That’s typically because one screenwriter knows how to make a scene entertaining. They know how to use suspense or drama or anticipation or surprise or conflict to make the scene fun. And when we, the reader, are having fun, time doesn’t exist. When we’re not having fun, every line feels like a page.

To be fair, it’s always going to be harder to move an ensemble of characters along. You can’t just cut to the main character, show him experiencing an issue with his dad, then send him off on his adventure. You have to do that for ALL THE CHARACTERS IN YOUR ENSEMBLE. Which is why you want to think hard about if you can handle an ensemble script.

It’s hard enough creating one compelling main character. Imagine that job getting multiplied by eight. It’s why people have been trying to remake The Goonies for 30 years unsuccessfully. Because it turns out it’s hard to write a bunch of strong memorable kid characters.

That’s not to say you shouldn’t do it. Screenwriting will never be a safe space. It’s more like a “drive you insane space.” But just know that the work LITERALLY gets eight times as hard when you have 8 main characters. Sure, you COULD be lazy and not develop half of them. Or make them stereotypes. But it will show. I guarantee you it will show.

Now, whenever I talk about moving the story along faster, I’ll occasionally get someone asking the legit question of, “If you cut out all the setup and only concentrate on moving the story forward, you’re going to get to your second act break by page 10. And the middle of the second act by page 30.”

“You have to add meat somewhere.”

Fair point. So let me try and come up with an analogy for you.

Let’s say you’re writing a story about a cat trapped in a tree. Your main character, Joe, comes out of his house, spots the cat, and decides to rescue it. How would you write a story like this that doesn’t end in ten seconds?

Because you could easily have Joe climb the tree and save the cat. Story over. Which seems to be in line with the note I’m giving today. That the writer should’ve ditched all this never-ending setup and gotten to the actual story.

No.

What you want to do is create entertaining obstacles and then use the time that your character is trying to overcome those obstacles to tell us about the character, or to provide exposition. In other words, you’re hiding the boring stuff inside the actual entertainment.

Let’s see what that looks like in action.

But first, let’s add a couple of scene boosters. 8 year old Jessica, the cat’s owner, is crying off to the side. This is her favorite cat in the world and she’s desperate to see it safe. This ups the pressure on Joe.

Also, we learned in the previous scene that Joe is on his way to a very important job interview that he cannot be late for. He’s dressed up considerably for this interview in a nice white pressed button down shirt and pants.

You can already see that saving this cat is becoming a bigger and more complicated ordeal.

Now, our cat is about ten feet up the tree. Joe knows he can comfortably climb up ten feet. So that’s what he does. But just as he’s reaching out for Scratchers, our annoying black cat, the cat freaks out, scratching Joe’s hand, causing him to lose his balance and fall to the ground, right on the freshly watered grass, which heavily imprints a lot of green on his white shirt. And meanwhile, the cat has climbed up another ten feet and is therefore, even higher on the tree.

Joe checks his watch. His important interview starts in less than 15 minutes. He’s got to go. He apologizes to the girl. She pleads with him. Please save my cat. “I can’t. I have to go to this interview.” “For what?” the girl cries. “It’s for a rare engineering job. This type of job never comes up.” Jessica pleads with him. Joe checks his watch. Checks his shirt. What does he do??

The point here is that you can extend any part of your story out for as long as you want. You can give us any amount of exposition (what job interview our character is going to) AS LONG AS YOU ARE ENTERTAINING US IN THE MEANTIME.

If you entertain, perfectionist readers like myself won’t even realize that your first act was 15 pages too long.

I know I didn’t really talk about today’s script. Which seems unfair since, once we hit the second act, that’s where all the action starts.

But therein lies the problem. If you put me through 35 pages of setup hell, I am no longer mentally invested in your story. I checked out a long time ago when I decided that I didn’t want to be subjected to setup torture. You could give me Avengers Endgame level action scenes at this point but it won’t matter. I’m already mentally checked out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Page Quality.” Are your pages as entertaining as they can possibly be? Or are they merely setting up future entertaining scenes down the line? If all you’re doing with a scene is setting up a future good scene, that scene needs to be rewritten. I’m going to give you some homework. Go watch the first act of Back to the Future. Notice how there isn’t a SINGLE SCENE in the first act that isn’t entertaining. And that movie has more exposition and setup requiremnts than your last ten screenplays combined. So having to set lots of stuff up is not an excuse to write boring scenes.

Genre: Music Biopic (Nooooooooooooo!!!)

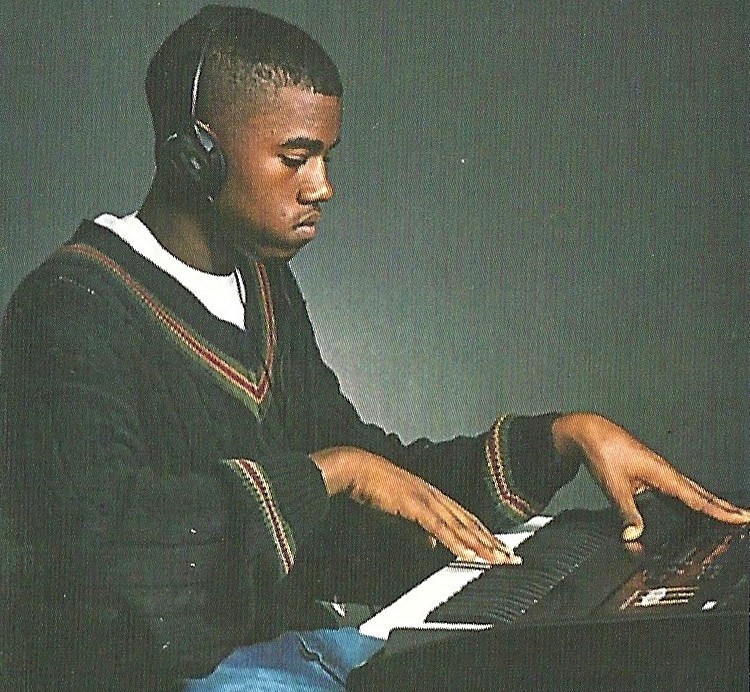

Premise: A young Kanye West goes up against impossible odds to make his first album.

About: This script finished Top 20 on last year’s Black List. The writing team worked together contributing on two TV shows, Instinct and L.A.’s Finest. They realized if they wanted to break out of writing for run-of-the-mill television shows, they needed to do what every smart writer with big dreams does – WRITE A MUSIC BIOPIC BECAUSE ALL MUSIC BIOPICS ARE GUARANTEED TO MAKE THE BLACK LIST!

Writers: Michael J . Ballin & Thomas Aguilar

Details: 117 pages

As I was staring at the title page of The College Dropout, trying to decide if I was going to review it, I took a deep hard look at my dislike of biopic screenplays and asked myself a simple question: Why?

Why I do I hate them so much?

Shouldn’t I like scripts that are unabashedly and deeply about ‘character?’ Isn’t that what I preach on this site? Write big memorable characters and everything else will take care of itself? What genre explores character more than a biopic??

And yet I dread these things. Even when they chronicle someone as complex and strange as Kanye West, I dread them.

I think it boils down to a couple of things. One, biopics are the laziest form of subject matter in all of screenwriting. The story is already written for you. It’s also built-in name recognition, which means you don’t have to do any work at all coming up with a good concept. You’re going to get reads regardless.

Which means it takes zero creativity to write a biopic. And that’s what I enjoy most in screenwriting. I love when somebody comes up with a clever premise. Or takes a story in an interesting direction.

Biopics are the antithesis of that. There is no clever premise. The story is already laid out for you and, assuming the subject is famous enough, we already know what direction things are going.

Wow, I’m really hyping this review up, aren’t I?

Well, as they always say, if you go in with zero expectations, the experience can only exceed them.

It’s 1997 and a 19 year old Kanye West is in his freshman year at Chicago State University. His mother, Donda, is a faculty member there. So Kanye gets a sweet deal for his college degree. There’s only one problem. Kanye hates college. He wants to produce music and rap.

So that’s what he does. All day long every day. He’s got a mentor named NO ID, who eventually helps him make some contacts in New York. Except that Kanye is young and a bit odd. When he gets into rooms with big people, he starts babbling about how he’s going to be the best ever and they quickly dismiss him.

But Kanye’s beats, which are so unique, keep getting him more meetings. They all want to use his beats. They just don’t want to talk to the guy. And they definitely don’t want him rapping on any of these songs, which is what Kanye really wants.

Kanye hustles to the point where he gets an album contract with Columbia. But then Columbia backs out at the last second. So Kanye switches over to Roc-a-Fella. But then Roc-a-Fella goes broke and THEY can’t release his album. Kanye, who’s put every cent he’s saved into this album, has one more outside shot to break through – get in front of the biggest rap star in the game, Jay-Z.

You know when your friends drag you somewhere that you don’t want to go to and you’re standing at this place and you want to make it clear you don’t want to be there so you cross your arms and refuse to engage in conversation and refuse to smile because you’re so determined to follow-through on your original feelings, even though, if you’re being honest with yourself, the place isn’t all that bad.

That’s how I felt reading this.

I didn’t want to be at the Kanye party.

But after things got going, I noticed the script was doing a lot of things right.

Remember yesterday when I said that they didn’t even bother creating any doubt that Thor would succeed? How good stories always build in a strong level of doubt?

This script does a lot of that.

There’s this moment deep in the screenplay when Kanye’s sunk every bit of his savings into his first album and then Columbia tells him they’re reneging on his deal. Then he goes to Rock-a-Fella and signs with them but they run out of money so THEY can’t release his album either. What is he going to do???

I know what you’re thinking. It’s no different than when Obi-Wan and Vader had their lightsaber duel in that abomination of a TV show, “Obi-Wan Kenobi.” There’s zero stakes cause we know they both live. Same thing here. We know Kanye becomes one of the biggest music artists in history. So is it really that dramatic that he’s struggling?

Yes.

We know that Kanye overcomes this, obviously. But we also know that hundreds of thousands of music artists over the years have been in a similar situation and things *didn’t* work out.

Which gets you wondering just how important it is to never stop stopping. In any artistic pursuit. Because when that moment came up and it looked like Kanye’s debut album was going to get swallowed up in the same music industry sinkhole that claims so many new artists who never recover from that trauma, I realized that the reason Kanye survived while so many others didn’t was because he was relentless.

He figured out a way to get into a Jay-Z recording session and play his CD for him, which is the moment that led to Kanye becoming a superstar. There are a lot of people who would’ve been so devastated by signing a contract and then being told the studio had changed their mind and then went to another studio and they couldn’t release the album either that they would’ve moped around for years feeling sorry for themselves. Kanye got right back up and kept hustling.

That’s what I liked about this script. Is the way it makes you think about being an artist. How the world doesn’t like struggling artists. They like the successful ones. But nobody wants to be around when the sausage is being made. They want the artist to do all the ugly stuff in quiet obscurity.

There’s a key moment in the middle of the script where Kanye’s mom points out that he hasn’t made any money from music for over two years. He has this opportunity to get a college degree because of her association with this college. Kanye’s professor says the same thing. You have an opportunity here and you’re wasting it while trying to win the lottery.

These are the thoughts that constantly invade an artist’s mind and they can be crippling, because they sow the seeds of doubt. And the older you get, the more you wonder if everyone was right and you were wrong. That this whole pursuit was stupid.

That’s not easy to handle. And the artists who succeed have to find ways to conquer those voices.

Speaking of the college angle, that was another thing that made this biopic different. I can’t tell you how many rap biopic screenplays I’ve read that take place in the projects. Whereas Kanye actually has a pretty financially stable life. The other guys in the industry make fun of him because he alway dresses preppy. He doesn’t look at all like any of the other rappers.

That could’ve easily hurt the screenplay because the good thing about a movie like 8 Mile is that your character, who lives in the projects, is poor and desperate, and that makes him the ultimate underdog. Conversely, who’s rooting for the polo-wearing middle-class kid?

But I think what they did that was clever was they leaned into Kanye’s “outsider” status, which made it look like he wasn’t the kind of person who succeeds in this industry, at least in the eyes of the people who held the keys.

The script does struggle with some typical music biopic things. They do the whole thing where, when the artist is making music, we cut to how he sees the world, and the world is, of course, full of magical crazy colorful imagery. Literally every artist biopic does this so I don’t know why you’d join the club. But, to their credit, they went all in. When one of these moments happens, they don’t half-ass it.

I also thought they missed an opportunity to really explore a unique character flaw in Kanye. The one they focus on is Kanye’s obsession with being a rapper and not just a producer. Which was fine. The only problem with it is I’ve seen it before. The producer or instrument player who really wants to sing. It’s just sort of played.

What they should’ve done was leaned into Kanye’s awkwardness. He’s a super socially awkward guy. He says weird things at inappropriate moments (as we all know). And it loses him a couple of major wins early on in his career. For example, he blurts out to a major music exec that he’s going to be way more successful than Michael Jackson when he hasn’t even had a song on the radio yet. That’s the end of that meeting.

But these moments are explored casually. The fact that Kanye has some sort of social connection issue that could potentially prevent him from ever succeeding would’ve been a juicy character flaw to explore in my opinion. And one that I don’t remember ever being explored in a movie like this.

Which is what I’m asking when I open any screenplay. Try to find those little detours into a back alley that nobody’s explored yet in this genre. When you find those hidden trails, they’re like gold. If you can string enough of them together, you’ve got a screenplay cave bursting with treasure.

As it stands, The College Dropout never stood out. But it created enough dramatic doubt that I wanted to see how Kanye succeeded. And I wasn’t let down. He takes a big chance at the end that ends up giving him a career.

When it comes to music biopic screenplays, Blonde Ambition is still the gold medal standard for me, which was that biopic about Madonna. It was the top rated Black List script in 2016.

The reason it was so good was because it wasn’t a commercial for the artist. It was cruel, it was relentless, it dug deep, and exposed Madonna for the ruthless businesswoman who would do anything to succeed that she was. That realism is what made the script so surprising and unpredictable, the very things that make any story fun to read.

(By the way, that is NOT the Madonna pic they’re making. They’re of course putting together a celebration of the artist’s life, which will be guaranteed awful)

The College Dropout isn’t in the Blonde Ambition category. But it’s still pretty snazzy.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I love when writers establish early on in a script that they’re going to try. Here, we see that ON THE TITLE PAGE. The title is listed as: “the college dropout” – No capitalization for a script about someone who rejects education was a clever choice.

Genre: Superhero

Premise: Thor must team up with his ex-girlfriend, also Thor, to save a bunch of children who’ve been kidnapped by an evil supervillain who is moodily flying around the universe killing gods.

About: Thor 4 opened with 143 million this weekend which is a number the industry doesn’t really know what to do with. They like giant or minuscule numbers that fit into easy narratives but as we’ll talk about today, this isn’t an “easy narrative” movie. The film is the biggest opening ever for a Thor film (good) but 45 million short of the last Marvel film, Dr. Strange (bad). An overlooked story with Thor, which admittedly has a lot of much bigger headlines to talk about it, is Taika’s screenwriting choice. Nobody’s ever heard of screenwriter Jennifer Kaytin Robinson before. So good on her for convincing the director to give her a shot.

Writer: Jennifer Kaytin Robinson and Taika Waititi

Details: About 2 hours long

I’ve noticed that people have been pounding their fists in the internet sand demanding for the magical ‘batsh#t crazy’ (as Chris Hemsworth called it) now mythical 4 hour cut of the film that was originally edited together.

I am happy to say that Taika has finally responded to these people demanding the “Taika Cut,” telling them what I’ve been telling everyone for the past two decades, which is that directors cuts are always terrible and that the theater cut is the best cut of the film.

Which begs the question: Is this cut actually good?

A quick plot recap first. This God named Gorr, played by Christian Bale, is hunting down a bunch of Gods because they’re responsible for killing his daughter. And Thor is next.

So Gorr heads to a place called New Asgaard, which, if I’m to understand this right, is a tiny theme park on earth that simulates where Thor is originally from? I think. Anyway, Gorr kidnaps all the children who are there that day and takes them to his planet.

Thor, then, teams up with Valkyrie, rock-monster Korg, and Jane, his old girlfriend, who now happens to be Thor, because she was dying of cancer and read somewhere that the Thor hammer makes you super-healthy or something. So she goes to New Asgaard to get the hammer and, in doing so, becomes Thor and cures her cancer.

Now when Captain America was able to pick up the Thor hammer, he didn’t automatically become Thor so… I’m not sure what’s going on there. But the point is, Jane, aka Thor, joins Thor, Valkyrie, and Korg on their journey to rescue the children.

On the way there, they try to recruit Zeus, since, you know, Gorr’s going to be coming after him next. But that fails miserably. Which means they’re going to have to go it alone. I’ll leave it up to you to guess whether they succeed or not.

I know that in this love it or thunder it era, you’re not allowed to have nuanced feelings about films. But I don’t know how you discuss Thor: Love and Thunder without having a nuanced take. Because there are some really bad things in this movie. But there’s also really good stuff too! So it’s hard to lay it over the “terrible” barrel and give it a spanking. It hasn’t misbehaved enough to do so.

Let’s start with the really good, which is Christian Bale. I feel bad for Bale because this may be the best acting job he’s ever done. I mean that. And it’s going to be lost in a mid-tier Marvel movie. The opening scene where he loses his daughter is heartbreaking. The following scene where he kills a God is mesmerizing. And any scene he was in after that was captivating.

However, Christian Bale is in a completely different movie from everybody else, starting with Thor. Thor is in Dumb and Dumber. That’s really what I would compare this to. It’s Marvel’s version of Dumb and Dumber. Except instead of Jim Carrey and Jeff Daniels, we get Chris Hemsworth and Natalie Portman.

What’s so baffling about Natalie Portman is how bad she is in this movie. But what’s even more baffling is that any of us thought that wouldn’t be the case. Portman had zero chemistry with Hemsowrth in the FIRST two Thor movies. Did we all think that Taika had some magical dust he would be able to sprinkle over them that would change that?

You can’t change bad chemistry.

And it’s weird how Portman’s delivery of this fast-and-free go-with-the-flow character comes off so forced. This is how she came into the industry, playing a can’t-shut-up 13 year old temptress who belts out non-stop dialogue like air (Beautiful Girls). Why does she seem so uncomfortable doing it here? She basically destroys any scene she’s in.

As for Thor, I guess they’ve gone full comedy with him. There are no more attempts to even pretend this character should be taken seriously. He’s cracking jokes no matter how close to death he gets. And it undercuts any tension that desperately tries to help this movie work. I felt higher stakes in The Hangover than I did Thor: Love and Thunder.

For example, Takia made this bizarre decision to give Thor a hologram video call ability whereby he could pop into the captured kids’ cage whenever he wanted and crack a bunch of jokes so they stayed calm. And Im thinking, “Do they realize how much suspense and fear and tension this choice destroys?” By showing us a visual of him and the kids hanging out, making jokes, you are showing us that the protagonist has succeeded a full hour before he’s succeed. It’s like you don’t want us to worry even a little bit.

I’m not going to lie. That threw me.

As a screenwriter, one of your mandatory jobs — especially in big budget Marvel movies — is to build as much doubt as possible into your story. The goal must seem impossible. When you do this correctly, we are desperate to keep watching because we have no idea how our characters are going to succeed. We watch to see them figure it out against all odds.

So I don’t know why you would deliberately eliminate all doubt. I suppose I understand that Thor is a full-on comedy at this point. But like I said, I had more doubt that Stu, Allen, and Phil, would find Doug than I did Thor would save these kids.

If you look back at Indiana Jones – the first one – Indiana Jones cracked jokes. It’s part of what made that character so charming. But he didn’t do it EVERY SINGLE LINE. He did it every few scenes or so. That way, when he *did* do it, it had impact.

If we know a joke is coming out of a character’s mouth every single time they speak, you lose that impact that a good joke has. Which means that, now, the jokes have to be EXTRA GOOD to land, because they’re competing against hundreds of other jokes. And that was another problem with this movie. The jokes just weren’t landing.

I will give it to Taika, though. He took big swings. He did so with a major character having cancer. He had a magical mystery tour bus that flew on rainbows and was driven by giant screaming goats. One of his characters was a rock man who lost his entire body and his face was taped to the back of another character. He’d do weird things like crash his characters into a 1960s model of a planet, breaking the filmmaking 4th wall.

It was as if he said, “Every time we come to a fork in the road, we are always going to pick weird.” I love that attitude. It’s better than the other route, for sure.

The most important question to come out of all of this, of course, is “Has Taika lost his magic touch?” Since I’m resting the future of Star Wars on his shoulders, that answer matters to me. I was terrified, after hearing some bad reviews of Love and Thunder, that the Taika train had been relegated to the maintenance track. But I think I understand what happened here. He made Ragnanok. And Ragnarok was perfect. But he didn’t want to repeat that. He had to have a challenge to stay interested in the franchise. So he said, “I’m going to push things further than I’ve ever pushed them before and treat it as a giant experiment.” And that’s why I feel safe with Taika and Star Wars. I think this was an experiment for Taika and he had a blast.

I didn’t have a blast with him. But I left the theater entertained.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There was a clever use of exposition here. Taika and Robinson had Korg tell a story to children about where Thor was in his life to deal with a lot of information that the audience needed to know (you can hear an abbreviated version of this in the Thor trailer). This is way better than trying to force expositional dialogue into a casual conversation. But what I really liked about this choice was that they used it to set up another important expositional chunk of information. When Jane shows up into the movie, we immediately go back to Korg now telling the story of Jane. When I say they used the first story to set up the second, what I mean is, this Jane exposition story scene doesn’t work if we didn’t have the first one with Thor. The audience would’ve been confused. So I thought that was really clever that they got a 2 for 1 there. The other day I was talking about how you can tell a writer’s improving by how invisible his exposition is getting. And this is a good example of that.

A good portion of you Scriptshadow readers are intermediates. You’ve been at this for over five years. You’ve gotten a good handle on the craft. You understand many of the screenwriting pitfalls and know how to actively navigate them. And yet, here you are. Still in this frustrating nomenclature of unpaid unknown screenwriters.

And you’re sick of it.

We’re all sick of it.

So what’s keeping you from making that leap from intermediate to pro?

Before we can answer that, let’s talk about what “Intermediate” means. I consider an intermediate screenwriter to be someone who’s written more than five screenplays and who has a solid understanding of the fundamentals.

They understand the 3-act structure. They understand basic page-marks to hit (i.e. the first act should end around page 25). They understand how to build flaws into characters and how to arc them. They understand nuances like how long a scene should be. They no longer make beginner mistakes with dialogue, such as being too-on-the-nose, too over-the-top, or making characters say things that people would never say in real life.

They’ve outgrown that phase where they believe anything that’s happened to them in their life is worthy of being turned into a screenplay and are, therefore, more discerning about the concepts they consider for a script. And they have an overall theme to their story in mind – or at least an idea that they’re trying to get across (i.e. the destructive nature of greed).

The thing about being an intermediate is that you can write a solid script. And that’s commendable. Because the majority of amateur scripts that I read aren’t good. The problem, though, with a solid script, is that it doesn’t leave an impression on the reader. The reader appreciates the knowledge of the craftsman who has written the script. But they never cross that magical threshold whereby they now see the characters as real people encountering real situations. And if a reader never feels an emotional connection to a script, they’re never going to recommend it to anyone. And therefore, nothing’s ever going to come of it.

Which leads us to – HOW DO WE GRADUATE FROM INTERMEDIATE TO PRO?

To be fair, every writer’s situation is different because we’re all better at some things than others. So the path for one screenwriter could be completely different from another screenwriter. However, there are some common themes in the writers who are stuck at that intermediate level. Let’s go over the most common issues.

I’d say that one of the top, if not the top, reason, someone is stuck at the intermediate level, is because of concept choice. They are routinely choosing concepts that don’t get people excited. This works against you in a couple of ways. The first is that less people are going to request your script. Which means less reads. Which means less potential for a “yes.” The second is that even if they do read your script and like it, you’ve given them an easy reason to say no, which is that the concept isn’t powerful enough to make it up that steep Hollywood incline that every project must trek in order to get made. So it’s easy for people to not start that trek in the first place.

A couple of weeks ago I reviewed a script that had just sold called, “Classified,” which was “Die Hard meets Raiders of the Lost Ark.” It was the ultimate high concept. And now it’s being turned into a big movie. Do I think the writers who wrote Classified are that much better than the intermediates I see on this site? No. They might have a slightly better understanding of structure and character due to being in the game a little longer. But these guys are not obviously better screenwriters than everyone here.

However, they understand the value of a big concept. Actually, I shouldn’t use the phrase “big concept.” Because I’m not saying you need to write a 150 million dollar movie to get noticed. “Splashy” concept is probably better. A concept that feels like a fun interesting idea. Don’t Breathe would fall into this category. Get Out. Knives Out. Yesterday.

A splashy concept gets more read requests. People can envision it as a movie so it’s easier to push up the chain of command in Hollywood. It just makes everything easier and, therefore, more likely to get you out of that intermediate level.

If you don’t like splashy concepts, you have to AT LEAST give us a marketable concept. For example, a true World War 2 story. Hollywood can look at that genre and say, “We’ve made successful movies in this genre for over 70 years,” and therefore take your script seriously. Meanwhile, if you’re pushing your coming-of-age script at the same people, they’re going to look at you cross-eyed. That’s just not going to get anybody’s motor revving.

Next we have INVISIBILITY.

No, I’m not asking you to acquire superpowers. Though, if you do, make sure to write about it. I’m talking about one’s ability to apply all the screenwriting tools to a screenplay INVISIBLY. What often happens in the beginner, and even intermediate phase, is you learn about all these screenwriting tools you’re supposed to apply in a script. For example: start a scene late, leave a scene early. Or, more broadly speaking, how to give a character a flaw.

Because you’re learning this stuff, you apply it in a clunky manner. So while you’re technically doing everything right, the reader can see the gears and pulleys moving to make your story go. The most obvious example of this is exposition. When we first start writing exposition, it’s in big shining lights and way over-the-top. “But Barry, the only way we can defeat the monster is if Jeff wields the Rylok Sword, and that sword is in the Forlorn Dimension.” “Then we have to get to the Forlorn Dimension?” “But how?” “We first must use the Zeezuldorf Mirror to cross over and then…”

Over time, we learn how to distill exposition down to its essence so there isn’t too much to it. We learn tricks to hide it. We learn ways for our characters to talk about it that don’t sound like exposition (using humor to distract them, for example). In the end, our exposition becomes invisible.

In order to move up to professional writing, you need to accomplish this ‘invisibility power’ across the board. You need to introduce your character flaws in a way that doesn’t sound like, “HERE’S MY MAIN CHARACTER’S CHARACTER FLAW EVERYONE!” Same thing with your act breaks and your plot reveals and your dialogue. You keep making adjustments to all of these things until they no longer feel like writing, but rather like we’re reading about something that really happened. You’ve mastered suspension of disbelief.

Another way to make the leap to pro is to focus more on your voice. As I’ve talked about before on the site, an argument can be made that we’re either born with voice or we aren’t. So it’s hard to manufacture voice. Which I agree with.

But that doesn’t mean you can’t lean into what you’re good at. Much of “voice” has to do with your specific sense of humor. So you want to pick concepts that allow you to use your unique sense of humor as much as possible. Look at John Hughes, one of the Mt. Rushmore faces of “unique voices” in screenwriting. Imagine if Hughes was determined to break into the business as an action writer. He was writing movies like John Wick or San Andreas. Do you think he would’ve succeeded?

Probably not.

Because he was too far away from the voice he was most comfortable writing in. Maybe that’s what’s going on with you. You’re choosing these script ideas that aren’t allowing your voice to shine. And if you just picked concepts in subject matters that you were confident in and could have fun with, you’d excel at a much faster rate.

Next up we have dialogue. Dialogue is definitely something that can hold intermediates back from getting to the big leagues. What I’ve found is that it’s not that intermediate dialogue is bad. It’s fine. And that’s the problem. Is it’s fine. It’s never memorable. It never jumps off the page. You never get those characters having that really fun conversation, like you see so often in, say, a Tarantino script.

Basically you need to figure out how to make your dialogue BIGGER. How to give it more impact. Most of the time, your problem is that you’re using your characters to convey information in order to move the plot forward. So your dialogue is technically doing what it’s supposed to do, but nothing more.

One of the easiest ways to improve this is to add DIALOGUE-FRIENDLY CHARACTERS. Because when you do that, you don’t have to TRY to write good dialogue. The characters are going to write it for you. Give me a Jack Sparrow. A Louis Bloom. A Peter Parker. A Tallahassee. A Waymond Wang (Everything Everywhere All At Once). Those characters are going to upgrade your dialogue IMMEDIATELY.

Beyond that, try and improve your “dialogue effort.” Ask yourself, “Is this the most interesting way for my character to say this line?” There’s a clear difference in dialogue effort between, “That didn’t go well,” and “That was about as choreographed as a dog getting f@%$ed on roller skates” (Succession). Not that every line needs to be a show-stopper but, with a little effort, you can always make a line more impactful.

A few more to go. The next thing that holds a lot of intermediates back is not taking chances. Learning the laws of screenwriting is kind of like being forced to type all your scripts in golden handcuffs. You’re always going to write something that’s solid. But you’re never going to write something that’s exciting.

The whole goal of learning the rules of screenwriting is to throw them away. Let me be clear about that cause I know it sounds confusing. If you try to break rules before you understand them, you’re going to write big ugly messy screenplays. It’s funny because these writers always think they’re revolutionizing screenwriting when, in reality, the only thing they’re revolutionizing is the need for stronger over-the-counter headache medication for having to endure the abominations they call screenplays.

You need to learn the rules first because once you do, you can start making conscious choices about which of them to break so that your script stands out. The most famous version of this is Psycho. Our main character is killed off 45 minutes into the story, and we then follow the villain. Another good example of breaking the rules is From Dusk Til Dawn. The genre changes midway through the movie.

There are other ways to take risks as well. I remember when I first read the Gravity script and realized we were following this person stranded in space in real-time as they tried to get back to earth. I just thought, “this setup is brilliant.” I hadn’t seen it before. But it *was* a risk. It didn’t even make sense according to scientists on the internet. But the concept was so fun it didn’t matter.

The idea here is to move away from writing predictable rule-following screenplays where the reader is 30 pages ahead of you. You got to take risks somewhere. In the structure, in the concept, in the characters. You gotta try something that’s a little scary. I remember Michael R. Perry telling me that he was terrified when he wrote The Voices because it was so risky and so different from every other script he’d written up to that point. But it became one of the hottest scripts in town and lead to him getting a ton of jobs.

Second to last, write things that you’re an authority on. What separates a lot of screenplays is specificity. Let’s say that ten writers, all equivalent in skill, write a script about the war in Afghanistan. But only one of those writers was a soldier on the ground in Afghanistan. That writer is going to be able to give detail and context to what happened that none of the other writers can touch. Readers can feel that – when there’s authenticity to a story. So it’s a huge advantage when you can write about something so specifically.

For example, let’s say you were a blackjack dealer in Vegas for five years. You’re going to have insight into the way that blackjack and Vegas casinos operate that separates you from 99.9% of the rest of the world. That’s a huge advantage. So come up with a really cool movie idea about being a dealer. Cause you can tell that story with a level of specificity that is going to make it authentic. And authenticity is VERY hard to find in the screenplays I read.

Now, if you’ve done all of this stuff already, and you’re still struggling to move from intermediate to pro, there may be one final barrier you’re not addressing. Which is HUSTLE. It may simply be that you aren’t hustling hard enough. I know a lot of writers have trouble with this part of the business. But let me remind you that hustling has never been as easy as it is now. When I started out? I actually had to physically go to agencies and ask them to read my scripts.

Between managers and agents and contests and screenwriting sites like this one, it’s easier than ever to get your scripts out there in front of peoples’ eyes. So do it! I know it sucks. But all of this eventually comes down to a numbers game. The more people who read your script, the bigger the chance that you’re going to get that “yes.” So get your hustle on and make something happen. Cause this isn’t a ‘waiting around’ game. Just like the heroes in your screenplays, you need to take the initiative and be active.

So do it!

Happy weekend everyone. Thor Love and Thunder Monday. :)