The Amityville Horror meets The Orphanage

Genre: Horror

Premise: A blind mother moves into a remote farmhouse with her young daughter, but the mystery of the home’s previous inhabitants intrudes upon her attempts to repair their relationship.

About: Today’s script finished number 2 on the 2021 Black List and comes from Lily Hollander, who was one of the writers of the 2016 movie, Mother’s Day.

Writer: Lily Hollander

Details: 107 pages

HORROR!

Horror is back, baby.

And combining horror with blindness has proven to be lucrative. There’s the Don’t Breathe franchise. There’s Bird Box, which I’m sure we’ll be getting 15 sequels for. As I’ll talk about in a bit, blindness provides a unique opportunity for the viewer to have an extremely superior point of view of events, which ratchets up the dramatic irony to level 60.

Let’s *see* if the script is any good. Wow, my pun game is on point today.

30-something Elsa, who’s blind, has just moved into a remote house with her 9 year old daughter, Sasha. Elsa picked this particular house because it’s been outfitted for blind people (for example, the wallpaper in every room has a different tactile feel so you know what room you’re in).

What Elsa doesn’t know is that that this house used to be an orphanage for blind children. And something really nasty happened here a century ago. We don’t know what that nasty thing was. But since we’ve seen movies before, we assume it involved lots of nutritionally deprived blind orphans being murdered.

Elsa is fighting a battle on two fronts. She just ran away from her abusive husband, who’s hired a P.I. to find her. And her daughter hates her for sticking her in this big empty scary house. The latter is alleviated somewhat when oddball neighbor, Opal, shows up and says she wants to help them move in. Elsa doesn’t like Opal but Sasha does, so Elsa lets her hang around.

Almost immediately, Sasha starts seeing things. She sees an old woman dragging a fire poker around. She sees little ghost children playing in the chimney. Naturally, she freaks the hell out. Problem is, Elsa doesn’t believe in ghosts. So Sasha can’t share these sightings with her. Luckily, Opal believes her and tells Sasha she’ll protect her. But when nobody’s around, we get the sense that Opal isn’t the nice helpful neighbor she says she is.

Things go from bad to worse when one of these ghosts seemingly possesses Sasha. When Opal recognizes this, she takes steps to stop it. But it may be too late. Sasha is determined to keep the bloody reputation of this house going, even if she needs to murder her mother to do so.

See How They Run is the ultimate dramatically ironic situation. We can see the ghosts. We know they’re there, watching Elsa. But Elsa can’t. So every scene Elsa is in, we’re in a superior position to her. We know she’s in danger when she doesn’t. You know how back in the day at horror movies, the audience would yell out, “DON’T GO UP THE STAIRS!” because they knew the monster was up there. The blind angle creates that same energy but on steroids.

Unfortunately, the script suffers from my least favorite screenwriting misstep – The “Waiting Around” narrative. The Waiting Around narrative is when you place your characters in a static space and don’t give them anything to do other than wait for scary things to happen.

It’s preferable that your characters have an active goal – something they’re trying to accomplish. When the scares come, they interrupt that activity as opposed to being the sole reason for the story to exist. For example, in The Exorcist, the mother has an active goal – to cure her daughter. So she does everything in her power to save her daughter’s life.

With that said, it *is* possible to write a Waiting Around narrative that works. Poltergeist is a well-known example. It’s just harder to do it, is all. It’s always going to be harder when you take out the component of an active main character. Without that activity, the story never feels like it’s going anywhere.

See How They Run almost solves this problem by giving us bits and pieces of plot development that provide just enough entertainment to keep us turning the pages. For example, we learn that Elsa’s abusive husband is trying to find her. We’ve got weirdo Opal who keeps forcing her way into the house. She’s got a secret and we want to find out what it is. We also have the mystery within the house itself. Something tragic happened here a long time ago and we want to know what it is.

And Hollander is good at creating scares, even from the smallest moments. There’s a scene when they first move in where Elsa is walking around with her cane, getting a feel for the house, and someone – it’s unclear who – has left a small box right in front of an old rickety railing. We see Elsa swiping her cane back and forth as she walks, unknowingly heading straight for the box.

If she trips on this thing, she will go head first into the railing, break through it, and tumble to a serious injury or even death. Our heart skips a beat when, by pure coincidence, her cane misses the box as it swipes, and she trips and tumbles, only barely avoiding a more serious injury. It was such a small scene yet it was incredibly effective at building tension and suspense.

There was another cool screenwriting trick Hollander used that’s worth mentioning. She reminded me that you can create interesting dynamics with three people that you can’t create with two. I would argue that one of the toughest things to do in screenwriting is make a two-person dynamic interesting. That’s because there are only so many of them to choose from. For example, here, we have the mother and the daughter who hates her. I mean, how many times have we seen that? A million? A billion? For that reason, it’s hard to make these 1-on-1 relationships fresh.

However, when Opal comes in, the dynamic shifts because Elsa doesn’t like Opal. However, Sasha does. This places Elsa in a tough spot. This woman makes her uncomfortable. Not to mention, she’s potentially unstable. But Sasha hates Elsa for moving her out into the middle of nowhere with no friends. So when Sasha likes Opal, it’s an opportunity for Elsa to give Sasha a friend and also curry favor with her daughter.

Just like that, a stereotypical two-person dynamic becomes a complex three-person dynamic.

The issue I couldn’t get past with See How They Run was that, no matter what happened with the bare-bones plot, we’d always go back to two people waiting around in a house for ghosts to scare them. There’s a bit of a mystery to it, sure. But the mystery wasn’t captivating enough to keep me excited.

I was watching another horror movie the other day called The Night House that covered some similar ground. It was about a woman living in a secluded house after her husband committed suicide. Her goal was to investigate her husband’s secret life. I was way more captivated by the mystery in that script because I had *NO* idea where it was going. Whereas with See How They Run, you always had a good idea of where things were headed because you’ve seen this movie before.

Again, this isn’t a bad script. I just feel like I’ve seen it in several iterations. The blind angle gave it a slightly fresh angle. It just wasn’t enough for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It remains extremely hard to write a compelling script where your hero is reactive the whole time. The better option is to make them active. And yes, it’s possible to give characters active goals in static settings like this one. One of the most common ways is to have your hero investigate some mystery that has to do with the haunting at the center of the story. They should start investigating this early, by the way. 15 pages into the second act at the latest. That’ll keep them active enough.

Today’s script is Joker meets The Social Network meets The Wolf of Wall Street

Genre: Biopic

Premise: The completely outrageous and completely true story of “pharma bro” Martin Shkreli — from his meteoric rise as wunderkind hedge fund manager and pharmaceutical executive to his devastating fall involving crime, corruption and the Wu-Tang Clan — which exposed the rotten core of the American healthcare system.

About: This script finished in the top 5 of the recently released Black List, a list that tabulates development execs’ favorite scripts of the year. The script was written by Andrew Ferguson. Andrew had one script he put up on the Black List amateur site a couple of years ago that readers of that site enjoyed called Boost. The logline for that was: “Two safecracking sisters are recruited for a heist by the Corsican Mafia in order to establish a modern-day French Connection.”

Writer: Andrew Ferguson.

Details: 120 pages

You may be wondering why, of all the scripts on the new Black List, I’m reviewing a biopic. The answer to that question is the same answer to the question of, “What makes a good biopic?” A lot of writers get this wrong so I want you to pay attention. Biopic writers believe that what makes a good biopic subject is a famous person they like. That’s the only criteria they use. But today’s writer knows the correct answer to this question, which is, “Write about the most interesting person you can find.”

Because remember – biopics are inherently boring. They just are. They’re meat and potatoes bland narratives that take us through years and years of a person’s life, making it hard to jumpstart any sort of compelling story. Out of the gate, the plots’s a dud. The only chance you have of keeping readers invested is if the character is one of those “can’t look away from” characters. And today’s character is that.

Our narrator for this story is RZA, one of the members of The Wu-Tang Clan. RZA is coming to meet Martin in prison. But, before we can learn what he needs from Martin, he tells us all about Martin’s story.

We meet Martin Shkreli as a 12 year old kid whose Albanian father is a janitor. Martin is embarrassed by his father’s job. But he’s even more embarrassed by the fact that his father has no desire to improve his life. In Martin’s eyes, that’s the ultimate sin.

Martin wants to be rich so, straight out of high school, he cons his way into an interview with Jim Cramer – yes, the wacky financial host – back when he was running a billion dollar hedge fund. After convincing Cramer to hire him, Martin learns the value of “shorting,” which is when you invest money in the hopes of a company failing. This teaches Martin that there is heaps of money to be made by taking a morally irresponsible approach to investment.

Martin eventually quits Cramer’s fund and starts his own fund in his mid-20s. Naturally, it fails, so he starts another one, and that fails too. Despite losing tens of millions of dollars of his clients’ money, Martin identifies a market that nobody is capitalizing on: You can buy the rights to a pill then raise the price of that pill to whatever you want.

So that’s what Martin does. He buys a pill called Thiola and ups the price from 15 dollars to 350 dollars. It is of no consequence to Martin that the pill saves lives and that, by raising the price, many people will die. Journalists ask him if he cares about this and he literally says no, he does not. All he cares about is profit.

What Martin doesn’t plan for is for his story to go viral. It even hits the late night talk show circuit, with Stephen Colbert and Seth Myers going after him. Martin, who operates under the m.o. of any publicity is good publicity, eats the attention up, even doubling down on social media.

But it ends up getting so much publicity that the SEC starts looking into him. What they find is someone with such an atrocious moral compass that they’re positive he has skeletons in his closet. They turn out to be right, identifying numerous laws he’s broken in his decade in the financial industry. So they arrest him and send him off to prison, where Martin is residing until next year, when he will be released and surely begin another sketchy company.

The Villain is an inherently challenging script to write in that the hero is the worst human being ever. Ferguson seems to know this and attacks it immediately. Martin’s father is a poor immigrant. Martin has no friends. Nobody gives Martin a chance. Martin gets accepted into multiple Ivy League schools but can’t go because he can’t afford it.

I think Ferguson realized that this guy was going to do such despicable things later on that he had to drum up as much sympathy for him as possible. Keep us around long enough to where we realize how weird and interesting this guy is. And then, by that point, even though he’s become a grade-A dickoholic, we’re so fascinated by the guy that we have to keep reading.

The script is also good by general biopic terms. I grade on a negative curve when it comes to biopics since I hate them but this is definitely one of the better ones I’ve read. I loved the choice of using RZA as a narrator. You’re always looking for ways to contrast and clash elements in a screenplay. That’s where you create excitement – combining things that don’t typically combine.

RZA’s streetwise no-B.S. narration (“But we first gotta run it back to the beginning. ‘Cause in the beginning was the word. I’m talking about the one place every rags to riches story in America begins — motherfuckin’ Brooklyn!”) was the perfect accomplice for a story about white collar Wall Street.

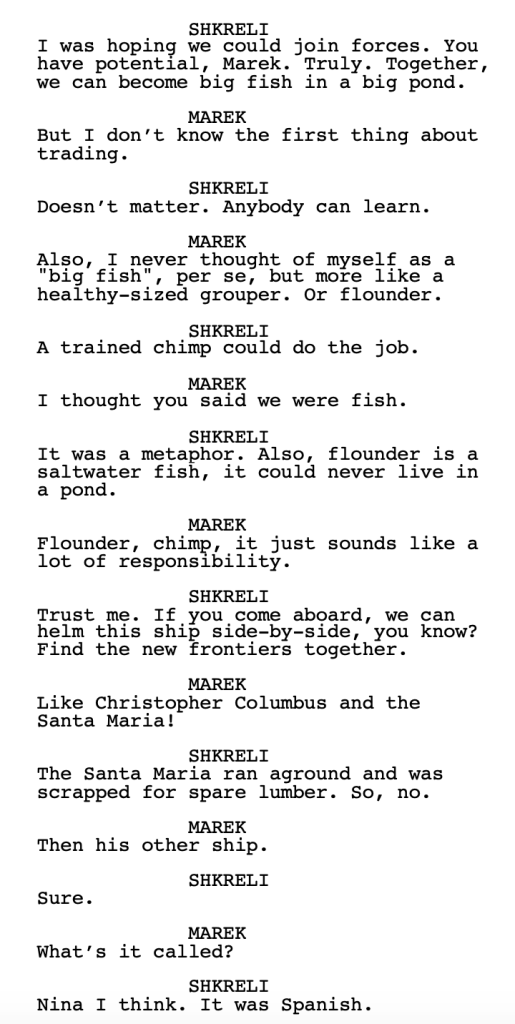

The dialogue is also good. It’s not quite Sorkin. But you get gems like this one where Cramer responds to Martin’s handshake (“Jesus, kid. You got the handshake of a teenage girl with polio.”) as well the below exchange, which I chuckled at.

But I think that the main reason the script works is that it gets your emotions going. That’s all you’re really trying to do with a script – connect with the audience on an emotional level. If you don’t achieve that, the audience will forget your movie within a week. If you do achieve it, they’ll remember your movie for a lifetime. Those are the stakes you’re playing with when it comes to emotional connection.

You can do this through love, like Titanic. You can do it through fear, like The Exorcist. You can do it through sadness, like Million Dollar Baby. Or you can do it through anger. And while anger is the least effective version of creating an emotional connection (since it’s a negative emotion) it still works.

We get so enraged when Martin price-gouges these people who will die if they can’t afford his pill that we’re now emotionally invested in the story. We want a resolution. We need to find out that someone’s going to come in and save these people from this insane man.

On top of that, there was something refreshing about a character who has zero interest in redeeming himself. Martin not only accepts his villain label, he goes out of his way to flaunt it. This guy is the embodiment of evil and I think that’s why the internet became so fascinated by him. Most people back down when they’re called out. He doubled-down. So we were kind of thrown into uncharted waters. If this guy has no desire to change, where does the story go? I wanted to know.

The one issue I had with the script was that it was a bit try-hard. It wants to be the next Social Network. It wants to be the next Wolf of Wall Street or The Big Short. But you can feel the writer pushing for that cool-factor (“Shkreli inhales breadsticks as he sits opposite Adele and SEC Officer inside the tourist-infested Olive Garden, surrounded at every turn by MAMMOTH MIDWESTERN MOUTHBREATHERS with their OVOID OFFSPRING devouring discount Italian by the dinnerplate”) and I’m not a fan of when I can feel the author’s presence. I want to be lost in the story. I don’t want the writer to remind me that he’s there.

With that said, this was pretty good. Definitely worth checking out if you’re also a biopic writer.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When it comes to narrators, writers tend to use the most obvious choice. Instead, consider the least obvious choice, like RZA here. I guarantee it will be more interesting.

Here’s the way I see it. 2020 and 2021 don’t count. They were weird years. A lot of weird stuff happened. How can one focus on his screenwriting career when he can’t even sit down at a coffee shop for six hours and complete one page of his script, for goodness sakes! Or can’t go to a movie theater where he can properly procrastinate? Here’s the good news. Those days are over. Covid is disappearing in 2022. Who said that, the CDC? No. Try the CRC. The Carson Reeves Consortium.

Myself, along with my esteemed board of trustees, have put in a word with the leaders of the free world, minus the president of Finland, of course, and have decided that enough is enough. Once these presidents and prime ministers learned of the reason I demanded an end to Covid – that screenwriting everywhere was suffering – they were immediately on board.

But the CRC didn’t stop there. They demanded that I – yes, yours truly – personally give screenwriters two opportunities to break out. And so I created the ANYTHING GOES AMATEUR SHOWDOWN along with the FABULOUS FIRST ACT CONTEST. Both of these competitions are going to revolutionize screenwriting. Well, maybe not revolutionize. But they’re going to give you two deadlines so that you actually get some writing done ya lazy asses.

ANYTHING GOES AMATEUR SHOWDOWN

What: An amateur showdown where any genre is accepted. I will choose the five best-sounding concepts to compete against each other at the end of February. You will then vote on the best one. I’ll review the winner.

When: Entries are due by 10pm, Pacific Time, Thursday, February 24th.

How: You need to send me your title, genre, logline, why you think the script deserves a shot on the big stage, and, of course, a PDF of your script.

Where: E-mail your entries to carsonreeves3@gmail.com and put “Anything Goes” in the subject line.

How Much: Free

THE FABULOUS FIRST ACT CONTEST

What: Starting March 1, I will spend a month guiding you, scene by scene, through writing your first act, the most important act of a screenplay.

And?: Whoever has the best first act, I will develop the rest of the script with you, guiding you through several rewrites. Once we’ve got the script in shape, we’ll go out there and try and get it made.

When: Entries will be due on May 1. You can start sending your first acts to me on April 1. I’ll give you details on where to send them as we get closer to the deadline.

How: Anybody who is thinking of entering this contest, I want you to begin a two-month Battle Royale of all your script ideas. I want you sending these ideas out to friends and asking them which one is the best. You will need a strong concept to win this contest.

How Much: Free

I wanted to start the screenwriting year off with some motivation for you guys and, unfortunately, found out that hiring several thousand Benihana chefs to go to your personal places of residence and do that really scary sword attack thing they do until you write three pages of a screenplay was going to cost me a couple million dollars, so I came up with an alternative. Some screenwriting resolutions. I’m going to give you ten resolutions but you only have to pick and adopt three. Choose wisely.

Resolution #1 – Write for at least two hours a day.

One of the fastest ways to get better is to write more. If you want to get good at anything, you have to prioritize it. So if you can’t carve out two hours a day to write, I would ask you, how much do you really want to be a screenwriter? Cause it doesn’t sound like you want it that much. Think about it. When has anyone ever become great at anything that they didn’t dedicate at least two hours a day to? Open up that laptop and don’t leave until those two hours are up.

Resolution #2 – You will find out if a concept is good BEFORE you spend six months writing it.

This has to be one of the most common mistakes I run into. People send me loglines for consultations all the time ($25 – carsonreeves1@gmail.com) that are so problematic, there is no version of a screenplay that can save them. The issue? They’ve already written the screenplay. Look, I understand that when we get an idea we love, we just want to write it. We have such tunnel vision that we don’t care what anybody else thinks. But screenwriting is an emotionally taxing endeavor. You can only write so many scripts that don’t go anywhere before you give up. For that reason, you don’t want to waste any of those slots on a lousy idea. Send your logline out to some friends and ask them for brutal honesty. Is this any good? And don’t get defensive. If five people aren’t that excited about your biopic into the origins of banana bread, consider another idea.

Resolution #3 – You will read at least 25 unproduced screenplays.

I thought that I knew everything about screenwriting before I’d read a single unproduced screenplay. I then read 1000 screenplays and learned 50-100 times as much about screenwriting as I knew up til that point. I read 1000 more. Same thing. 1000 more. Same thing. The biggest thing that reading screenplays did was shine a light on all the blind spots I had. When I read a beginner screenplay, I’d see them doing the same things I did in my scripts. “Oh,” I realized, “I can never do that again.” Or when I read a really good screenplay, I’d notice how much clearer and visceral the prose was than all my screenplays. It helped me identify where the bar was. Before reading scripts, I thought the bar was so much lower than it actually was. 25 screenplays is 1 screenplay every 2 weeks. You can do that.

Resolution #4 – Improve your biggest weakness as a writer.

What’s your biggest weakness? Is it plot? Structure? Character? Dialogue? Concept? Theme? Do your scripts lack conflict? Do they not build? Do your second acts get progressively more boring? Whatever you’re bad at, set aside some time every week and work on it. You can do that by googling, “How to write good second acts” and read 50 articles on how to get better. You can write a practice script that specifically focuses on the thing you’re weak at. For example, if it’s dialogue, you can write a practice script that has two characters in a house that’s almost all talk. So many writers ignore the things they suck at. But if you want to get good at this, you have to strengthen your weak links.

Resolution #5 – Write out a plan for the year.

I know we all make fun of Vin Diesel now (and believe me, I’m right with you). But there was a time when that dude was the biggest movie star in the world. And I remember him saying in an interview that, when he was a nobody, he sat down and wrote out this very specific three year plan. He’d write and shoot a short film. He’d submit it to Sundance. He’d use it a promotional tool. He’d get an agent off the buzz. He planned the types of roles he wanted his agent to send him out for. He had it all mapped out. That’s what you need to do. Divide the year into four quarters and have a goal for each quarter. If you want to get even dirtier, set clear goals for every month. Too many writers operate under this lie whereby they wait for inspiration to strike. Unless you want to snap your fingers and see a decade go by, that’s not how you become successful. Come up with a plan and execute it to the best of your ability.

Resolution #6 – Add one new writing weapon to your arsenal.

I’ll never forget the day I learned about dramatic irony. It was like I’d seen all of these great movies and shows with these scenes that always worked and yet I could never quantify what they were doing to make them so awesome. Then I learned they were using dramatic irony – the act of telling the audience something that a key character in the scene was unaware of. John McClane meeting Hans Gruber up on the roof and thinking he was a hostage. There are a bunch of little screenwriting weapons like this that can improve your writing. Suspense. Scene agitators. GSU. Using conflict in every scene. Adding a ticking clock to a scene. Identify one of these, read up on it, then become an expert at it. Your writing will take off.

Resolution #7 – Shift your mindset to a positive place.

In any artistic pursuit, everybody who’s on the outside has a level of disdain for those on the inside. A lot of it comes from a belief that you’re better than a lot of them. And you don’t understand why they’ve made it and you haven’t. I’ll be honest. In some cases, you are better than someone who’s making millions of dollars screenwriting. I can think of two names right now – one who’s about to have a major movie release – where everybody who’s ever won an Amateur Showdown is hands down a better writer than those two. But here’s the thing. It doesn’t help you to expend all that energy being frustrated by that. In fact, it hurts you. It’s much better to focus your energy on writing a great script. I know some people won’t agree with me on this. But I’ve found that, in my life, when I focus on just coming up with good content and not worrying about other peoples’ success who are less talented than I am, I write much better and I’m much happier overall.

Resolution #8 – Come up with one great character.

Most of the scripts we write are born out of an idea we have for a movie. And that’s fine. I’m all for coming up with good movie ideas and writing them. However, this often leads to us retrofitting characters into that idea. Idea first. Character second. Yet when I look at all of the greatest movies throughout time, the one constant I see is great characters. Neo, Jack Sparrow, Travis Bickle, James Bond, The Terminator, Hans Landa. So I’m imploring you to try something new. When you come up with your movie idea, I want you to ask the question, “Can I create a great character within this idea?” So you’re attacking the script on two sides, both conceptually, and as a show-stopping character vehicle. A great character is going to turn a good script into a great one.

Resolution #9 – Speed up your plot.

I have read, maybe, 10 scripts out of 10,000 that I could argue moved too fast. However, I could point to several thousand screenplays I’ve read that moved too slow. The reality is that most scripts move slower than they should. This is because we assume we need to include more than we do. But as I was telling someone the other day, one of the things pros are really good at that amateurs are not, is that they can do in one scene what amateurs take three scenes to do. So their scripts move along a lot faster. I’m not saying you need to redefine the way you write. But any little opportunity you have to move the story along, take it. You don’t want to sit inside any section for too long in a screenplay. Save that for when you write your novel.

Resolution #10 – Finish 2 Screenplays, no less, no more.

You should be shooting for two scripts a year. That’s one script every six months. Which is totally doable if you’re writing 2-3 hours a day. The problem I’ve found with writers who only write one script a year or one script every two years is that they’re not developing their overall screenwriting skills because they’re only improving the skills that help them write that one story. Every script challenges you in different ways. So if you want to get better as a writer, you need to write more than one script. On the flip side, I don’t think you should write more than two screenplays a year. The writers I’ve run into who write 3, 4, even 5 scripts a year – their scripts are sloppy. They’re not developed properly. It’s more of an ego thing for them. And look, I’ve been there. I was once writing scripts every two weeks. I bragged to everyone I knew about it. But, looking back at those scripts? They were terrible. Two screenplays is the perfect amount. That’s what you should be shooting for.

I’m really excited for what this year is going to bring the screenwriting world. Especially here at Scriptshadow. I can’t wait to see which of you break out in 2022. Happy New Year!!!

It’s a cur-raaaaaazay newsletter. I take on the Benchedel Test. I ask if Spider Man No Way Home just screwed all superhero movies from this point on. I announce a brand new Scriptshadow Screenplay Contest (WHAT???) and it’s unlike any screenplay contest in history. I share an overlooked 2021 movie that I loved. I give you my thoughts on Ben and Matt’s latest period piece, The Last Duel. And to top it all off, I review the brand new Star Wars show, Boba Fett! Best Scriptshadow Newsletter ever? Possibly. Be on the lookout in your e-mail!

If you didn’t get the newsletter or would like to sign up, e-mail “NEWSLETTER” to carsonreeves1@gmail.com.

Does the ballsiest franchise sequel since Fury Road deliver on the wild chances it takes?

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: 50-something game developer Thomas Anderson starts to believe that the game he’s developed, “The Matrix,” may be rooted in reality.

About: Pretty much every major creative in town has come to WB with a Matrix pitch over the past decade and a half. But it took Keanu Reeves becoming an action star again with John Wick for WB to finally greenlight the fourth film in the series. The movie’s production was suspended when Covid hit and Lana Wachowski seriously considered scrapping the sequel. The cast, however, desperate to see it completed, convinced her to keep going. The script was written by Lana and her Sense 8 writers, David Mitchell and Aleksandar Hemon.

Writer: Lana Wachowski, David Mitchell, and Aleksander Hemon

Details: 2 hours and 27 minutes

Let’s be real.

When you’re showing up for a Matrix review, you’re showing up to either hear, “GREATEST MOVIE EVER” or “WORST MOVIE EVER.” Anything in between is an insignificant opinion.

Well, if that’s what you’re hoping for, you’ll be disappointed in this review. Because Matrix Resurrections takes some chances that are so wild, you can’t help but admire them, even if the end result isn’t as good as you want it to be.

This is a spoiler heavy review. You’ve been warned.

Our movie starts inside a new version of the Matrix where a fresh-faced female character, Bugs, runs into a sleeker younger copy of Morpheus. They watch a familiar scene from the original Matrix, where Trinity beats up a bunch of cops then runs for her life. But there’s something off about the scene. Trinity isn’t quite… Trinity.

Cut to the real world, where we meet an older Thomas Anderson (Neo), who’s a rich game developer. The game that made him rich? The Matrix. Thomas Anderson has no idea where these ideas and concepts for “The Matrix” came from. But he’s created a trilogy of games based around a trio of characters – Neo, Morpheus, and Trinity.

After a suicide attempt, Mr. Anderson has been seeing a therapist and is starting to believe this therapist is manipulating him. So when Bugs comes to him and tells him that his game is based on something that really happened, it’s like Thomas knew it all along.

Bugs releases him from the Matrix, where we learn that both Neo and Trinity are being kept in special isolated containment units. Their pairing seems to be the central force behind the new Matrix code.

Bugs brings Neo back to the newest underground city, Io, where we meet Nairobi (from the Matrix Sequels) who’s now 80 years old. Nairobi is upset that Neo is here because she’s worked hard to keep peace with the machines. His arrival puts everyone at risk.

Meanwhile, Neo becomes determined to release Trinity (“Tiffany” in the real world) from the Matrix, so the team forms a plan. Bugs and Morpheus will handle the physical side of getting Trinity. But it will be up to Neo to convince Trinity/Tiffany to take the red pill. That won’t be an easy task considering Tiffany doesn’t know Neo, doesn’t believe in the Matrix, and has a husband and two children.

Yet when Neo arrives, Tiffany finds herself drawn to him and finally gives in. Once the Matrix realizes the power couple have teamed up, it initiates its “swarm” protocol, whereby every single person on the planet becomes a kamikaze killer. It’ll be up to Neo and Trinity to escape a city where the entire population is after them.

When you first realize what The Matrix has done with Neo, you become giddy. “They’re not really going to go through with this, are they?” you wonder, excited. And when you realize that that’s exactly what they’re going to do, your expectations for Resurrections rise from a 5 to a 50.

I never would’ve guessed in a million years that they’d build a Matrix sequel around the meta concept of Neo making a Matrix video game. Not only was it a bold choice, but it made sense. Thomas Anderson used to be a coder. He’s had these intense dreams all his life about this “Matrix” world. Naturally, he would capitalize on that, making a game out of the concept.

The addition adds some new ideas to the mythology. Was the original Matrix ever the Matrix at all? Or was it only a video game modern day Thomas Anderson created? That was what was so great about the Matrix. It was such a head-trip that, afterwards, you and your friends would discuss what it all meant, putting forth various theories that ranged from dumb to downright ridiculous.

It was the early section of this movie that held so much promise. You got the sense that Lana actually had something to say.

The problem with most sequels is that they’re conceived through a faulty process. The lens through which every movie should be conceived is that a writer has something they want to say. For example, James Cameron really wanted to say something about humanity destroying the planet in Avatar. It’s the need to get this view out there that gives the story the necessary energy to keep an audience invested.

When there isn’t a *need* to tell a story – when instead you’re just doing it for money, or because your career is in a slump, or because the studio won’t stop bothering you about it – the script exhibits a decidedly less energetic pulse. We can tell that it isn’t a life or death desire from the artist to get this story out there.

So I was encouraged by this seeming desire to say something. The story felt original. The dialogue purposeful. I had no idea where the story was going but I was excited to find out.

However, the second we get to the underground city of Io, I knew Resurrections was as dead as Dozer. Zion was a movie killer in the sequels. As was Nairobi. Yet you’re bringing both those elements back in major forms? I don’t want to turn this into a “why the Matrix sequels were terrible” thread because I’ve already written about that ad nauseam. But the brilliance of the Matrix were the scenes that took place inside the Matrix, not in the muddy CGI infested underworld.

The unfortunate reality of Resurrections is that every 15 minutes of Resurrections is worse than the previous 15 minutes. The story builds (we’re moving towards the extraction of Trinity). But the energy and the momentum fade. The Wachowskis are masters at undercutting their own narratives.

A narrative needs to move, especially a sci-fi narrative. The pacing of the original Matrix was relentless. There wasn’t a single moment that could’ve been cut. Here, with the Io stuff and some of the talkier scenes, like when The Analyst plays a game of bullet slo-mo with Trinity’s life — they dragged on, killing any momentum the story had.

Another issue is that Resurrections has a huge character problem. Bugs, the franchise’s flashy new toy, has very little to do other than verbally facilitate Neo’s second emergence from the Matrix. I don’t know what the heck they were doing with Morpheus, who is some sort of half-Morpheus who isn’t really Morpheus but he’s trying to emulate Morpheus. So he does a lot of dancing and irreverent joke-telling. It’s bizarre.

Agent Smith is now some dude who kinda dislikes Neo but also kinda likes him. At one point, they even team up. I don’t profess to know what Lana had in mind with him but he didn’t work. Maybe that’s because they wanted Hugo Weaving in the movie but couldn’t get him at the last second so they had to adjust the storyline.

Neo, meanwhile, says very little throughout the movie. Not only doesn’t he say much. But apparently, Neo only has a single power now. To hold his hands up and blast energy away from his body. I waited the entire movie for badass Neo to show up and and start doing crazy Neo sh#t. Bu it never happened. It was reminiscent of another failed sequel that I shall not mention the name of. Only that it rhymes with “Duh Blast Redeye.”

And Trinity, who arguably gets the most exciting storyline here, is absent for the majority of the second act. She really only shows up in the third act. And since, like Neo, she hasn’t said a whole lot, we don’t feel close enough to her. That’s something that really bothers me about the Wachowskis in general. They give these stupid side characters 18 page monologues. Yet their main characters can go a dozen scenes and barely utter 10 words.

It’s pretty clear that Lana didn’t get enough money to make this movie. The one great thing about those Matrix sequels is the extremes they went through to create set pieces that nobody had seen before. I mean, they built their own highway! They spent 40 days shooting a single scene (the Neo vs. 100 Smiths fight). There’s none of that insane dedication here.

The train scene was sloppy. The fixed set piece scenes (like the warehouse) felt rushed with little attention to detail. The swarm motorcycle chase was so dark you could barely tell what was going on.

While I can blame some of this on a less-than-adequate budget, Lana could’ve ditched Io and spent that money on cooler fight scenes inside The Matrix. That’s exactly what they did in the original film. The original Matrix script featured a trip to Zion but WB wouldn’t pay for it. So they had to ditch it. Should’ve done the same thing here.

There’s a lot to learn here if you’re a screenwriter. The biggest lesson one should take is that what happened in The Matrix Resurrections is the same thing that happens to almost every amateur screenplay. Which is that the writer comes in with a head of steam, spends a ton of time getting that first act right, then gives 80% of that energy to the next 15 pages. Then 60% to the next 15. Then 40% to the next 15. So the script keeps getting… not necessarily weaker. But it doesn’t have the same energy that it started with. So, if you’re a screenwriter, make sure you’ve put just as much time into what happens on page 70 as you did on page 10. Cause there’s nothing worse than watching a movie getting more and more boring as it goes on.

I don’t know what history will say about Resurrections. It seems to have some champions out there. I do commend them for trying something different. Not many franchises will take the big swing Lana did. But just because you go for the home run doesn’t mean you’re going to hit it over the wall. Sometimes you barely make contact and the ball dribbles out to third base. That’s probably the best way to describe this movie – bullet-time dribbling down the 3rd base line.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The original Matrix proves the value of combining multiple purposes into a single character. In the original movie, Trinity both recruits Neo and is his love interest. She has two purposes. In Resurrections, Bugs recruits Neo and that’s it. She doesn’t have any other purpose. As a result, she gets lost in the story once that purpose is fulfilled. The lesson here is that when you have a character, give them multiple story purposes if you can. It’ll give them more to do and make them feel more integrated into the story.