Genre: Biopic!!!!!

Premise: An overweight sexually confused young boy overcomes massive amounts of adversity to become one of the most famous exercise personalities in history.

About: This script finished top 30 on last year’s Black List. It comes from newcomer Greg Wayne, who hails from Canada. Wayne’s favorite movies are Barry Lyndon, The Remains of The Day, and Amadeus, which pretty much guarantees he’s never read Scriptshadow before. His favorite screenwriter is… well, I’ll let him tell you. “I love Joe Eszterhas. His screenplays have such an effortless flow to them, and are incredibly easy to read. I swear you can finish the BASIC INSTINCT script in like twenty-five minutes.”

Writer: Greg Wayne

Details: 110 pages

This is your quarterly reminder that, as much as I would like to develop a computer virus that seeks out every biopic screenplay on every hard drive in the world and instantly destroys it, biopics remain the most dependable bet to make the Black List. They don’t even need to be good! You can just write about somebody famous, give the script the old college try, and voila, you’re celebrated as the next Aaron Sorkin.

Okay, maybe it’s not *that* easy. But if I had a dime for every average biopic I read from the Black List, I would’ve retired and been in Hawaii by now. The current trend seems to be picking people from the 80s and 90s under one of two categories. One, talented and immensely successful artists (Madonna, Kurt Cobain), two, eccentric and weird celebrities (Richard Simmons, Anna Nicole Smith, Mr. T, Vanilla Ice). I think the reason writers tend to go with the latter is because it’s easier to get the rights to them. And, obviously, you don’t have to worry about getting access to their music.

I’m yet to read a script about an eccentric celebrity that’s blown me away. But I guess there’s a first time for everything. Might today’s review be that first?

10 year old overweight Richard Simmons (real name, “Milton”) is growing up in the single worst place in the United States to be a food addict, New Orleans. You can’t find a breakfast there that’s under 2000 calories. Richard’s tough father tries to get Richard to lose some weight but he just can’t do it. Richard loves food!

At 19, and over 250 pounds, Richard heads to Italy, where he becomes an actor who stars in a bunch of commercials as “the fat guy.” After a particularly humiliating commercial, Richard heads back to New Orleans. In his dream of dreams, he wants to be a performer. He just doesn’t know how. Then one day, a friend takes him to an aerobics class, and he’s in heaven! He’s dancing, yelling, having an out of body experience.

The next day, he tries to get his overweight friend, Maggie, to come to the class. But she’s too afraid of being fat-shamed. That’s when Richard has the revelation of all revelations. There is an entire market of people out there – overweight women, mainly – who are too afraid to go to a gym because of the way they look. So Richard creates an aerobics class specifically for overweight people!

Not long after, he becomes a superstar. Women don’t just like Richard, they don’t just love Richard, they see him as a religious figure, a conduit to God himself. And Richard runs with it. He opens dozens of Richard Simmons aerobics centers across the United States. He starts a TV show. He says yes to EVERYONE who asks him to do something. Pretty soon, it’s Richard Simmons’ world and everyone is living in it.

One of the reasons Richard is so successful is that he actually cares about everyone. When his production team shows Richard the hundreds of fan letters he’s been getting, they ask him if they should throw them away. Throw them away??? Hell no, Richard says. I’m going to write every single one of them back. And he does!

While all this is happening, Richard is massively struggling with his sexuality. He is clearly gay and yet refuses to admit it no matter how many times he’s confronted with it. He is so determined people not know he’s gay, that Richard doesn’t date anyone. As in, ever! He lives a completely asexual lifestyle. This resistance manifests itself in some weird habits, such as Richard keeping a giant dollhouse with tons of headless barbies in it that he often has little tea sessions with. The language during these sessions is… not suitable for children to say the least.

At the height of Richard’s empire, which culminates in him winning an Emmy, he realizes that there is no possible way he can keep up with all of this. There are too many studios, too many shows, too many appearances, too many people to keep in touch with. All that energy he’s been blasting out for the last 30 years finally overwhelms him, and he retreats out of the spotlight. To this day, no one has seen him since 2014.

One of the things I find interesting about biopics is that the writer will often operate on the assumption that the reader already knows where the story is going because they know what has happened in that person’s life. For example, if you write a movie about Jaleel White, the actor who played Urkel, everyone supposedly knows that he ends up on the show Family Matters, where he then becomes a big star.

The problem with approaching your script this way is that you’re using an assumption to power your narrative. You assume that we, the reader, will want to keep reading simply because we’ll want to get to the Family Matters part. Instead of creating a mechanism within the plot itself to power the narrative.

What that might look like is a young Jaleel White is aiming to get into Juilliard Acting School. This would give him a GOAL. Which would create narrative THRUST. We’d feel like we were moving towards something, which would keep us engaged. Maybe he gets into Julliard or maybe not. Once that plotline is over, you would then introduce a new, replacement, goal

St Simmons doesn’t have that, at least initially. It assumes that we’re all in on Richard Simmons becoming an aerobic superstar and we’re just going to keep on turning the pages until we get there. To me, that’s dangerous screenwriting – leaving the job of wanting to turn the page up to the reader. It should be the writer’s job to make you want to turn the pages. And what happens with readers who have no idea who Richard Simmons is? You’re going to lose a lot of them.

Now, once Richard Simmons becomes a superstar, Wayne does start introducing goals. For example, Richard wants to win an Emmy. And then Richard wants to get a bill passed that will make it mandatory that all schools have P.E. The lesson here is that you should have these goals throughout the screenplay. There shouldn’t be a big 30 page chunk anywhere in the script where it isn’t clear what your character wants. That’s when scripts wander.

This is a common mistake in biopics due to what I brought up above. The writer assumes you’ll just want to keep reading because you want to get to that part you know about. Just to be clear, that *will* be enough for some people who are huge fans of the biopic subject. But it won’t be the case for most people.

Despite this hiccup, St. Simmons succeeds just enough to be worth your time. That’s due, in large part, to the character of Richard Simmons, who is just so interesting. He’s actually a great character study for anyone looking to create memorable characters in their own scripts. There are three main areas that make him a standout character. Let’s go over each one.

1) He’s bizarre – Weird/different/unique characters tend to do well in scripts because they’re so memorable. Richard’s obsession with cutoff barbie heads and his excessive aggressive swearing despite being one of the sweetest guys in the world in his public life was enough to keep you intrigued throughout the story.

2) His internal struggle – If possible, you want to add some level of internal struggle to your main character. Characters who have an unresolved issue that’s tearing them up inside tend to be interesting to watch (and read about). Richard’s inability to accept his sexuality makes him quite fascinating to watch.

3) Likability – You’ve never met a person who wants to help more people than Richard Simmons. By the way, this is an important point so I want you to pay attention. You know how we sometimes artificially make our hero more likable by having him help an old man across the street. Readers smell that b.s. If you want to make your character a good person, they need to genuinely be a good person. That’s Richard Simmons. He genuinely wants to help people.

St. Simmons is messy and sometimes untethered, like a lot of biopics. But Richard Simmons is such a unique person that you ultimately get wrapped up in his journey. Not to mention, the dude is kind of inspiring!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Sometimes in screenplays, you encounter technical things that you can’t turn to a screenwriting book for because they’re too specific to have been covered anywhere. Wayne encounters one of those problems early on in St. Simmons. The script is about a guy named Richard Simmons. However, some of the script covers him when he was younger, when his name was Milton Simmons. So what do you do? Do you call your main character Milton for half the screenplay and Richard for the rest? Or do you just go with Richard, even if, for all the younger scenes, people are calling him Milton? There’s no easy solution, right? Whenever this happens, the way I like to think about it is I ask, “What would be best for the reader?” They’re the ones who have to engage with your choice. So you want it to run as smoothly as possible for them. I think Wayne made the right choice here. It would’ve been weird to call someone Milton for much of the screenplay if we know him as Richard. So he decided to refer to him as Richard the whole time. Here’s how that looked.

Sorry to say but there will not be a Scriptshadow post today (Tuesday). However, there is a big fat 6000 word newsletter in your inbox. You know how shocked everyone is that Squid Game was rejected for 10 years? Well in this newsletter, I discuss a project that took 30 YEARS to get made. I also talk about the season premiere of the amazingly written Succession. I give you a Kinetic update. I discuss the latest scripts to hit the market in October. I give you a sneaky good show no one knows about on Apple TV. I analyze all the latest trailers. And, finally, I review a really heartfelt feel-good holiday script.

If you want to read my newsletter, you have to sign up. So if you’re not on the mailing list, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “NEWSLETTER!” and I’ll send it to you.

p.s. For those of you who keep signing up but don’t receive the newsletter, try sending me another e-mail address. E-mailing programs are notoriously quirky and there may be several reasons why your e-mail address/server is rejecting the newsletter. One of which is your server is bad and needs to be spanked.

Genre: Sci-Fi/Drama

Premise: A family is entrusted with a planet that produces the most valuable energy source in the galaxy – spice.

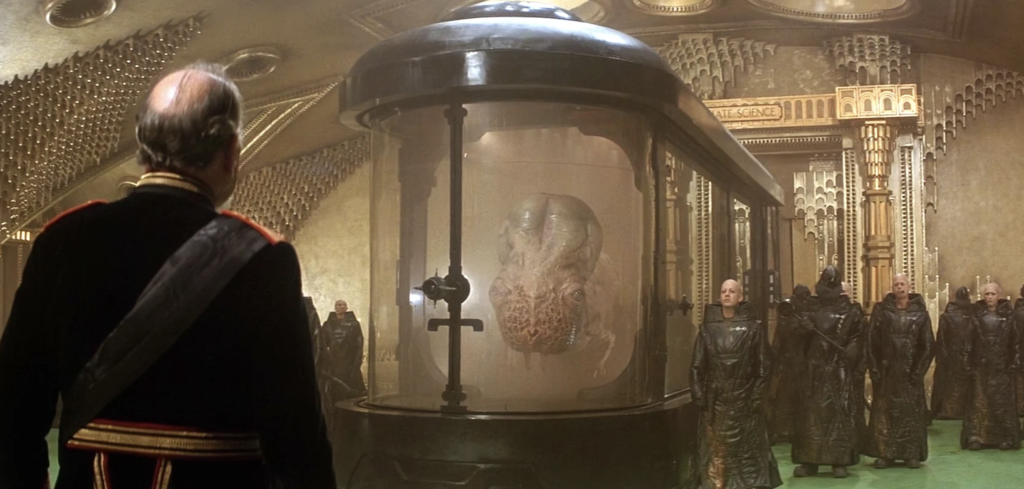

About: Dune’s long perilous journey to the big screen is finally over. The film was released in theaters this weekend, as well as simulcast on HBO Max. It pulled in 40 million dollars, the largest post-pandemic haul yet for an HBO Max simul-release. The movie comes from visionary sci-fi director Denis Villeneuve (Arrival, Blade Runner 2049). Everyone’s asking the question, “Is a 40 million dollar opening enough to greenlight a sequel?” Well, I hope so considering the first movie didn’t have an ending. Dune is doing pretty well with critics (82%), and a little better with moviegoers (91% on RT and 8.3 on IMDB).

Writers: Jon Spaihts and Eric Roth and Denis Villeneuve (based on the novel by Frank Herbert)

Details: 2 hours 35 minutes

I should’ve been worried when I read this headline over the weekend: “Denis Villeneuve claims Tenet is a masterpiece.” But, if I’m being truthful, I was worried about this film all the way back when I saw the original trailer. My initial thoughts were, “This looks like it has the potential to be REALLY boring.” And, unfortunately, that’s Dune’s biggest battle. Fighting off its fits of boringness.

The problem here is Denis Villeneuve. Denis is a very talented filmmaker. But he wasn’t built to direct big-budget movies. He was built to create smaller artsier fare. There are large swaths of this movie that feel like a Terrance Malick film. And while that works with limited audiences made up primarily of cinephiles. It might as well be nuclear waste when selling it to mainstream audiences.

In Denis’s defense, there are so many things working against Dune as a feature film that one finds it hard to believe it would work in any capacity. The worst part of it is the story itself, which seems designed to be boring. The Atreides family is handed the planet Dune, which produces the main energy source of the galaxy, ‘spice.’ The plot that occurs for the next 60 minutes is anyone’s guess. But it can basically be boiled down to “people in rooms talking,” a screenwriting death sentence for a feature film.

After what seems like forever, the film finally comes alive when the Emperor orders the other clans to attack and destroy the Atreides family. But Denis finds a way to make even that boring, as we’re soon watching Timothee Chalamet and his mom spend ten entire minutes inside an underground tent having the most boring conversations known to man. It is one poor story choice after another here.

If that wasn’t bad enough, the movie ends out of nowhere, as if everyone on the production team realized, all at once, “Um, this story goes nowhere so why continue telling it?” In cutting the movie off so abruptly, they seem to have erased an entire character, the blue-eyed girl played by Zendaya, who was so heavily involved in the marketing that you might have expected her to have upwards of 2 hours of screen time. Try 5 minutes. All of which is in Timothee Chalamet’s dreams.

There are some lessons to learn from this screenwriting disaster. So let’s get into those.

There are way too many “two people in a room talking” scenes. A lot of you gave me crap for bemoaning 2PIART scenes but this movie shows you exactly how dangerous they can be to a story’s momentum. This is a giant production. So why do you have so many 5-6 minute scenes of two people talking in a room?? It’s egregious.

Even worse, nobody shows any emotion in this movie. Every character is muted. Everyone speaks monotone. Everyone looks serious. This is a classic beginner screenwriting mistake. You believe that if you muzzle emotion, your movie will come off as more “serious” and “thoughtful.” But all it does is make every single scene that has characters in it boring.

You can get away with one character being like this. You can’t get away with a dozen characters being like this. At a certain point, people need to show emotion. That’s what audiences connect with because we’re all emotional creatures. When something bad happens, we want the character to be mad. Or sad. When something good happens, we want to share in their happiness. There is no emotion in this movie at all. And when you combine that with the stark lifeless backdrops, it feels like we’re in the world’s biggest indie flick.

Another screenwriting 101 mistake – when you have a major team-up in your screenplay – characters who are going to have a lot of screen time together – you want those two characters to have the most interesting conflict-filled relationship possible. Why? Because they’re going to make up 50-60-70% of the movie we watch. So if there’s no interesting conflict between them, you could have up to 70% of your movie with two characters who have zero interesting moments together. Dune makes the inexplicable decision to team Timothee Chalamet up with his mother. The two have absolutely nothing interesting going on between them. They just mumble back and forth to each other for 150 minutes.

And the thing is, they actually had the opportunity to create some conflict here. One of the first things Chalamet’s mom does is send him into a trial where, if he fails, he dies. Mom trying to kill you is a pretty good starting point for a conflict-heavy dynamic that’s going to need a lot of work to resolve. However, Chalamet holds no ill-will towards his mother after her attempted assassination of him. He shrugs it off and goes back to mumbling.

Another thing I tell writers is that when you’re writing sci-fi or fantasy, stick with two sides: the good guys and the bad guys. That way, we’ll never be confused. However, if you have three sides, or in Dune’s case, four sides, there’s going to be a good chance we’ll be confused by what’s going on. That’s exactly what happens here. The Emperor decides to take down House Atreides. Is the Emperor part of a House himself? No idea. Is he completely on his own? Maybe. When people did start to attack House Atreides, which House were they a part of? Information not available.

I’m not even sure what House Atreides’ job is. Are they only harvesting and distributing the spice? Or do they now own the planet and, therefore, own the spice itself? This matters because if they own the planet, it makes sense that others would want to go to war with them, so they could have the planet themselves. But if they’re just harvesting for the greater good of the galaxy, it makes less sense that anyone would want to attack them.

And this isn’t insignificant information here. This is at the heart of what the movie is about. If we don’t know what the rules are, how can we appreciate the nuances of any sort of attack on them? I know Dune is not trying to be Star Wars. But I understood what the central conflict of Star Wars was within ten minutes. It just seems like nobody sat down and said, “We have to figure out how to make this conflict understandable and accessible.”

Even stuff that should be easy to understand is confusing. Why is spice red but the people who live among it and are supposedly overcome by the toxicity of spice – their eyes are blue? That seems like a no-brainer to make those two things the same color.

It reinforces, to me, that Dune is not meant to be a feature film. I’m not sure it’s meant to be anything other than a novel. But, if it has any chance of being a media product, it definitely needs the length of a TV show to set all of this elaborate mythology up.

The directing in this movie isn’t that good either, to be honest. The movie looks pretty. But I’m not sure that’s the point of making Dune. One thing I noticed was how empty the movie felt. George Lucas was famous for his obsession with filling up the frame. He wanted his world to be so vibrant and exciting that it would seem like there were ten other movies going on in the background of the movie he was telling.

Denis is the opposite of that. He finds gigantic empty rooms and puts two characters in them and has them speak for 10 minutes. After doing this enough times, the world begins to feel so empty as to be insignificant. I mean is all this squabbling that’s going on for a few thousand people? Because that’s what constant empty frames makes it feel like.

Another Denis issue is that he doesn’t make a single exciting choice in the entire movie. I’m no defender of the original Dune. But Lynch makes a couple dozen exciting choices in that movie. Where is that here? For all the lauding of Villeneuve, his sci-fi imagery and his characters are standard. That’s the one area where you could’ve made your movie stand out. Instead you opted to create a boring political indie film with some pretty desktop wallpaper backdrops.

Did I like anything in the film? Yes. I liked the sand worm stuff. In particular that first scene where the sand worm is coming and the ship breaks down and they have to improvise. That was a cool scene. And then there are a couple of other sand worm scenes that rocked as well. Denis did a great job of creating that looming dread of one of those things coming your way.

Ironically, I think the sand worm scenes expose what’s wrong with Dune. Which is that, the scenes prove that they’re the only sequences you can actually do anything with in the feature format. Those attacks were built for the big screen. But nothing else was. It’s scene after scene after scene of two characters speaking in giant empty rooms. And it’s proved to me that Denis needs to be making smaller movies. This big stuff isn’t his forte.

Despite my desperation for a good sci-fi movie, I can’t recommend Dune. There’s way more bad here than good.

[ ] What the hell did I just stream?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Readers need to understand the central conflict of your movie. In Infinity War, it’s Thanos trying to snap half the population out of the universe. In Star Wars, it’s the Empire trying to permanently squash the rebellion. In Dune it’s…. What exactly? That’s right. There is no central conflict. Well, until the Emperor decides to take down House Atreides. But that doesn’t happen for 80 minutes. This is basic stuff. The fact that nobody on the Dune team understood it is somewhat baffling.

The voting begins NOW!

How excited am I for Halloween Horror Showdown? Let’s put it this way. My favorite candy in the universe is the Reese’s peanut butter cup. Halloween allows me to buy bags upon bags of Reese’s peanut butter cups from the supermarket and nobody questions me. “Of course these are for the trick-or-treaters. What? You think I would eat all of these by myself? Ha ha ha ha. What a silly idea. That’s way too much candy for one person.” But as only I, and Scriptshadow readers know, those Reese’s will never reach a child’s hands. Because they’re mine! All mine!!! Mwahahahahahahha!!!”

I got some KILLER entries this year. Horror is clearly the genre people on this site are the most passionate about. Most interesting logline that didn’t make it: “Seven influential philanthropists must fight for their lives after attending a charity event secretly hosted by a murderous cult of billionaires. Ready or Not meets Die Hard.” Favorite “Why You Should Read:” Because we all know that feeling when you kinda like the people you follow online, but also kinda want them to die.

Just know that there were a handful of entries that were very close to making the cut. So don’t get down on yourself if you weren’t picked. This was a close race!

If you’re new to these parts, you’re probably confused about what’s going on here. Well, the Scriptshadow Showdown Series is a quarterly screenplay competition where anyone can send in their script and compete. I go through all the loglines and pick my favorite five. I post those five loglines, along with the scripts themselves, so that you can download and read the scripts.

Your duty is to read as much of each entry as you can then vote for your favorite in the comments section (just write the title of your favorite script and your vote is counted). Feel free to add commentary on why you picked the script and also why you didn’t pick the others. Showdowns double as an opportunity for the competing screenwriters to get feedback and improve.

A new feature for this showdown, by the way, which I’m sure you’ll all love. I include the reason I picked each script!

Good luck to all of you. Let’s find a killer screenplay!

Title: Cinder (taken down – writer and script are making progress. :)

Title: My Dinner With Andre

Genre: Horror/Thriller/Black Comedy

Logline: A struggling journalist is invited to dinner by a canceled actor suspected of cannibalism. But as the night descends into chaos and madness, she not only questions if the accusations are true, but if she’ll make it out of the house alive.

Why you should read: It’s a ripped from the headlines story that mixes original Hollywood monster movies and into the real-life monsters of Hollywood resulting in a macabre, modern-age horror hybrid.

Why I picked it: In addition to being timely, this seems like the perfect little intimate horror flick that would be cheap to make.

Title: Alone

Genre: Horror

Logline: Stalked by a supernatural force that only strikes when she is alone, a monophobic young woman joins a group retreat to conquer her fear of isolation. But she soon finds there is no safety in numbers, as the combined anxiety of the group amplifies the demons that hunt them.

Why you should read: This script is fully vaccinated against pandemics. It contains a small cast, limited locations, and a high concept that could be produced on a budget. It takes the primal fear of being alone and packages it as a new brand of monster.

Why I picked it: Anxiety has become a much bigger problem in society since the pandemic so I was drawn to a story about anxiety, and I liked the clever twist of the group anxiety making the monster even stronger.

Title: The Short List

Genre: Horror-Thriller/Dark Comedy

Logline: A self-made Black executive is invited to join an eclectic group of colleagues from his elite private equity firm for a weekend retreat at the estate of their mysterious boss and soon realizes they’re fighting for the same promotion — and their lives.

Why you should read: “The Short List” was a semi-finalist in this year’s Nicholl Fellowship, landing in the top 150 out of nearly 8,200 screenplays. Also, some people who have read it have made favorable comparisons to “The Menu,” which I know you’ve listed among your favorite scripts.

Why I picked it: I was on the fence with this one but I read the first page and really liked the writing. Also, when he mentioned “The Menu,” one of my favorite scripts last year, that definitely caught my interest.

Title: Bloodmouth

Genre: Horror – Creature Feature

Logline: An agoraphobic woman struggles to survive as grotesque winged creatures wreak havoc on the world outside, forcing her to decide between staying in the comfort of her home or facing the unknown and reuniting with family who may or may not be alive.

Why you should read: I hate to talk about it anymore, but COVID really messed with our heads. Not knowing what’s out there, how other people are doing, the feeling of being trapped, isolated, and not being comfortable going for groceries. It was odd and scary (it was fucked quite honestly). During this time, I thought of writing a script where the protagonist has agoraphobia, and not set in a COVID universe, but in a normal universe. In this case, the person may possibly experience those feelings daily, which is terrifying to me. So then the reddit horror screenplay challenge started, and I was assigned ‘creature feature’. Perfect. A woman is confined to her home while something is out there. I wanted to make a modern creature feature, featuring the terror of The Birds and the darkness of The Descent. And voila, out of the darkness on bloody wings flew Bloodmouth. I was also inspired by an engraving titled ‘Knight, Death, and the Devil’. I hope you like it. It was a lot of fun to write!

Why I picked it: I like the timeliness of the concept. And, again, I’m drawn to stories about anxiety right now. Since they’re kind of similar, I’m hoping that one of these two (Bloodmouth or Alone) stands out and delivers on the promise of this subject matter.

Title: Gravesite Crows

Genre: Slasher

Logline: A murder of crows and a haunted shaman’s mask reanimate a disgraced Native American so he can get revenge against five high schoolers that killed him in drunk driving accident.

Why you should read: This script has lots of chase and thrill scenes that I think the faithful at Scriptshadow will have a fun time dissecting. — For those on the fence when it comes to slashers, I’ve brought in some unique ideas and effects that have never been done before. Gravesite Crows is not a knock-off Halloween (1978) or any other horror movie. There is humor to be found in the filmables and the unfilables in this script. — Finally, you should read Gravesite Crows because it looks unlike any other script you’ve ever read. I used colors and fonts to break-up the static, black-and-white page to emphasize the unique elements of the script and draw attention to the visuals in the story.

Why I picked it: What can you say!? I’ve seen E.C. grafting like a boss these last two weeks and I just can’t ignore the determination this man has. He’s so easy to root for and I had to give him a shot!

Lessons from arguably the best zombie film ever made!

TODAY (THURSDAY) IS THE ‘HALLOWEEN HORROR SHOWDOWN’ DEADLINE. Get your entries in by 11:59pm tonight! The five most compelling pitches will be posted tomorrow for everyone to read and vote on. As a reminder, here’s how to enter…

What: Halloween Horror Showdown

Genre: Horror

When: Entries are due Thursday, October 21st, 11:59 PM Pacific Time

How: Include title, genre, logline, Why We Should Read, and a PDF of your script

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

While I eagerly await the remainder of the horror entries, we’re going back to the zombie genre for another Halloween Horror 10 Tips! I had so much fun watching Night of the Living Dead last week, I thought we’d check out its sequel, a movie many consider to be the best zombie movie of all time. This is the movie where a group of people hole up in a shopping mall during the zombie apocalypse. Lots of good lessons to learn here!

1) Even More In Media Res – As we talked about last week, Night of the Living Dead throws us right into the action. Zombies are coming at us in the very first scene. Dawn of the Dead takes that approach and multiplies it by a thousand. We’re plopped down on a news set as zombies take over the world. Everything is falling apart in front of our eyes. People are screaming to get off the air. Newscasters are determined to stay on and keep giving the news. It’s absolute chaos. If you’ve never seen this movie, go watch it now just for the opening. It feels insanely realistic and scary. More importantly, Romero doubles down on his ‘in media res’ approach to zombies, showing us, once again, how effective it is. A tremendous opening scene (and a good follow-up scene as well).

2) Exposition Mastery – I noticed something very cool about the initial exposition being used to describe what’s happening in the world. 99% of the time in these movies, the exposition is offered through people watching the news on TV, which is a passive, and therefore, boring way to convey exposition. What Dawn of the Dead does that’s really clever is they PUT YOU IN THE ACTUAL NEWSROOM as the news is being given. Because we’re experiencing the news from the inside, as all the chaos surrounds us, the exposition feels a lot more active and compelling.

3) Create ticking time bombs WITHIN the story – When I talk about ticking time bombs, I’m often referring to the kind that frame the entire story (“The hero has 48 hours to find his missing daughter!”). But remember, you should be creating smaller “self-contained” ticking time bombs as well, as they help keep that section of the screenplay tense. For example, helicopter weatherman Stephen approaches news producer Francine and says, “Meet me out by the chopper at 9pm sharp. We’re getting out of here.” This “mini” ticking time bomb creates an intense little storyline now where we’re determined to see whether our couple gets out or not.

4) Set characters up through their reactions – I recently read a script where none of the characters stuck. I couldn’t remember them from page to page. The most common reason this happens is that the writer didn’t do enough to properly establish the character when they were introduced. A great way to establish someone is through their reactions. We see that here with Peter, the big burly SWAT team member who joins our group. He’s forced to kill a bunch of zombies who’ve been stuffed into the basement of a hotel. He must shoot each of them in the head. As he does this, one after another, he starts crying. That’s the reaction audiences latch onto. They now know this guy is a sympathetic dude who hates that he has to do this. Not only do we have a good feel for the character moving forward. But we like him as well.

5) Look for opportunities to split people up – There’s safety in numbers. Which is great in real life. But bad for horror movies. Audiences are less scared when your characters are together. Which means you should look for ways to split them up. When our heroes land their chopper for a refueling, Stephen and Francine go one way looking for supplies while Peter goes another. Now all we need is a few zombies lurking and we’ve got ourselves a couple of cool scenes to crosscut between.

6) Use your unique surroundings to create memorable moments – Not enough writers consider what’s unique about a location. Anything unique should get special attention because that’s where you’re going to give audiences things they haven’t seen before. One of the most memorable zombie kills ever occurs in Dawn of the Dead when Roger is refueling the helicopter. A zombie moves in to attack, has to climb over some boxes, and then while he’s up on the boxes, the helicopter blade slices the top of his head off. That’s way more interesting than yet another gunshot to the head. (pro-tip: A clever writer would’ve had Roger execute the kill himself, shoving the zombie up there with his own hands)

7) Old school social commentary – Probably one of the most famous examples of social commentary ever, Dawn of the Dead puts a spotlight on America’s obsession with consumption, highlighting a bunch of zombies (us) brainlessly wandering the hallways of a mall. Consume consume consume. Buy buy buy. I put this up as a reminder that if today’s highly charged social commentary topics make you squeamish, there’s other, less controversial, commentary you could be making, like Dawn of the Dead does here. If your commentary is clever enough, like “Dawn,” it will get people talking about your script for sure.

8) Start light in your second act so that it can build – Remember that your second act is going to build. So if you start out too big, you may not have anywhere to go. Romero knows we’re doing to be stuck in the mall for the whole movie so he starts off by having some fun. Have the two guys run around the mall like kids in a candy store. Everything they’ve ever wanted: absolutely free. You do this so you can start building, from “happy,” to “kinda serious,” to “serious,” to “very serious,” to “Oh shit, we’re f%$@d.”

9) Give your characters the occasional reward – Horror movies can devolve into a never-ending series of intense scenes. The monsters are getting stronger. People in the group are dying. The remaining characters are at each others’ throats. It’s important to, every once in a while, give your characters a reward that makes them feel good, and by association, makes us feel good. We get that here when our team finally gets into the gun shop. It’s a big fun moment as now they’re able to outfit themselves with a ton of weapons to take down the army of zombies. In general, there should be no singular emotion that lasts, uninterrupted, the entire screenplay. Emotion should fluctuate during a movie, from the highest of highs to the lowest of lows, and everything in between.

10) Don’t forget your relationship issues! – You have a choice when you create relationship problems between characters. You can either include a problem that’s already there at the beginning of the movie. Or you can introduce a strong relationship then add a problem to it later on. Dawn of the Dead has both. Francine is pregnant with Stephen’s baby and neither of them are sure they want to have it. That’s their issue. Peter and Roger, meanwhile, are best friends through this whole thing. There’s no problem at all. However, when Roger gets infected, Peter realizes that the time is coming where he’s going to have to kill his friend. Four characters. Two relationship issues. Both well done.