Genre: Drama

Premise: Awkward and lonely, Jared is only able to find a community online — until the day he realizes that his favorite Youtuber lives nearby. Desperate for a connection, he becomes determined to find a way into her life… whether she wants it or not.

About: This script finished with 7 votes on last year’s Black List. The writer, Alexandra Serio, has written and directed a couple of short films, one of which looks to be the inspiration for this screenplay.

Writer: Alexandra Serio

Details: 90 pages

One of the things I’ve been actively doing over the past month is weening myself off junk food internet content.

I’m doing this because, ironically, I watched a Youtube video about the effects of social media and what the video noted was that, a hundred years ago, you read the news in your small town and were immediately able to do something about it.

For example, if the local church burned down, you’d be able to get together with the community and help rebuild it. You’d have a physical outlet for the unresolved news issue.

But today, the news is always so far away – “Crazy Thing Happens in Washington!” – that you can’t actually do anything about it. So the energy that the news generates inside of you stays put, along with all the other junk you come across on the internet, creating a ton of anxiety that comes out in unproductive ways.

I bring this up because, as I’ve been detoxing, I’ve spotted more and more of these “black pill” videos. Since I don’t click on them, I don’t know much about the black pill philosophy. But from my understanding, it’s a negative defeatist way for men to look at the world.

Naturally, then, it’s a perfect backdrop for a screenplay! So let’s get into it!

Jared is in his 20s, lives in a trailer with his mom, and works at Wal-Mart. So, yeah, things aren’t going well for Jared. Jared deals with this through the “black pill” online community. Essentially, black pillers believe that certain men, aka “incels,” will always be invisible to women and therefore they should either accept this and not try to get with women or kill themselves.

But a tiny part of Jared is holding out hope. He watches this ASMR influencer online and she routinely puts out affirmation content where she whispers into your ears as you fall asleep that you are “worthy” and that “looks don’t matter.” Stuff like that.

Lo and behold, Jared can’t fathom his luck when he spots Dee AT HIS WAL-MART! As a Black Piller he can’t actually go up and talk to her so he follows her from a distance, even leaving work to follow her home. Once she’s home, he’s able to watch her livestream in person. As in stalking from his car across the street looking through her window “in person.”

When Jared sends her the livestream question, “Do you have a boyfriend?” And she ignores it, he goes ballistic. A primal incel force is triggered inside of him. He goes and buys a bunch of home improvement stuff and renovates an abandoned trailer near his home. He then sneaks into Dee’s home, waits for her, and kidnaps her (while wearing a mask) during her livestream!

He chains her up in his secondary trailer and starts reading all the news. Due to being kidnapped on a live stream, Dee becomes a national story. Jared spends the next couple of days not really sure what to do with Dee. He’s like the cat who finally catches the laser beam. Now what? He ultimately decides to execute a dramatic suicide on Dee’s channel. Will he be able to pull it off?

As you guys know, I love a good character description.

They’re an easy way for me to identify if I’m reading a good writer.

I really liked the description of Jared here. It’s a little long. But the main thing with any character description is that the reader HAS A GREAT FEEL FOR THE CHARACTER after they read it. So here’s Jared’s description in Blackpill.

JARED, a weary 20-something, enters and drops into a gaming chair exhausted. One look into his dark eyes reveals his exhaustion is soul deep; the look of a man who truly believes he’s never caught a break.

Let’s break this down piece by piece. First we get his age with the added bonus of an adjective. Right away, we’re learning things about this guy.

We’re then told he drops into a “gaming chair.” A “gaming chair” is a very specific piece of furniture. That’s what you want to do as a screenwriter. You want to focus on the SPECIFIC things your character has. Not the general things. If you would’ve told us that Jared, instead, dropped down onto “a couch,” that doesn’t give us nearly as much information about him.

The next sentence gave me even more insight into Jared: “One look into his dark eyes reveals his exhaustion is soul deep.” That’s a different situation than someone who’s simply “exhausted.” “Soul deep” means the exhaustion is irreversible.

Finally, we get this tag about how he “believes he’s never caught a break.” I love that description because we all know people like this, people who believe that life is against them and is determined to make their existence miserable, and how they use that as a sort of defense mechanism to explain not trying to improve. In 40 words, I have a great feel for this character.

Contrast this with yesterday’s character intros. Here’s one for the sister from that script, Brie:

SNIFF! BRIE MORGAN (38, pretty like a wilting flower) snorts a bump of blow like a pro.

The one good thing about this description is that we’re introducing the character during an ACTION, and actions are a great way to tell us about a character. The problem is that snorting coke is one of the most cliche actions in movies. Contrast this with the gaming chair. The gaming chair is SPECIFIC. Snorting coke is GENERIC.

We’re then told, rather clumsily in parenthesis, that Brie is “pretty like a wilting flower.” What does that mean? Is a wilting flower still pretty? So you’re saying she’s kind of pretty? Or are you saying a wilting flower isn’t pretty at all and therefore she’s ugly? Trying to be too clever by half when you’re not clever in the first place is a recipe for writing disaster. Clarity over cuteness, always.

Or here’s one from a script I’m going to review in the newsletter:

Subtle pockmarked scars surround sage eyes — eyes carrying oceans of weight. In another life he may have been a poet.

Holy Moses is this weak. Eyes carrying “oceans of weight.” Extremely clunky phrasing that doesn’t quite make sense. Avoid at all costs. “In another life he may have been a poet.” That’s a strange thing to say after the “oceans of weight” debacle. Where is the connection? Just because you have a lot of history in your eyes, you’re a poet all of a sudden? Weird description all around.

Just remember that when it comes to descriptions, the harder you try, the worse you do. Key in on your hero’s defining characteristic (like Jared, he’s almost given up on life) and give us a simple description that conveys that.

As for the rest of Blackpill, it was pretty good. I enjoy the sub-genre of characters in mental decline. There’s a built-in trainwreck aspect to the narrative and as much as we hate ourselves for it, we all look forward to seeing the crash when we pass it. One of the best versions of this sub-genre is Magazine Dreams. Very similar to this script.

Where I had some issues with Blackpill was with the plot. There wasn’t a whole lot going on in it. Man feels unseen. Man sees influencer he’s obsessed with. Man prepares to kidnap influencer. Man does kidnap influencer. Man executes plan to kill himself.

My issue here is that I couldn’t figure out which route the writer wanted to go down. If this was a stalker thriller in the vein of Single White Female, it needs more twists and turns. If it’s a character study like Joker, you need to dig into the character more. Or, in this case, into both characters. While I had a good feel for Jared, I didn’t know Dee that well. And in a narrative this simple, you probably need to expand the character work to include the co-star.

Cause I think that’s what would’ve elevated this. Let’s look at the circumstances by which a guy could be pulled into this dangerous online religion. But let’s also see how girls can be pulled into, arguably, the just as dangerous religion of influencing. I felt like Serio was starting to go there towards the end. But it was too little too late. I believe this becomes a much more intellectual experience if we’re showing Dee’s influencer obsession as well.

With that said, it’s an easy read and I wanted to find out how things were going to end. As long as you accomplish that, you’ve written a good script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This script is a great example of how point-of-view changes a story. If you write this from Dee’s point of view, it’s a survival story. If you write this from Jared’s point-of-view, it’s an obsessive stalker story. But there’s a third option. You can write it from both points-of-view. And then it becomes more of an intellectual experience, something that gets cinephiles and critics talking. So always explore every potential point-of-view before you write your script. You might be overlooking the best version of your screenplay.

Today’s writer does something really clever. He takes a recent hit movie and slides it over to the horror genre.

Genre: Horror

Premise: While meeting her boyfriend’s dysfunctional family at their ancestral manor, a young woman finds herself entangled in a bizarre and terrifying mystery when the family’s patriarch claims to have been cursed by a demon.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List with 9 votes. Screenwriter Edgar Castillo is new to the game. This is his first major achievement as a screenwriter.

Writer: Edgar Castillo

Details: 116 pages

Sydney Sweeney as Katie would INSTANTLY up this screenplay’s rating to an ‘impressive’

Sydney Sweeney as Katie would INSTANTLY up this screenplay’s rating to an ‘impressive’

Ever hear of a little movie called Knives Out?

What if you wrote that movie… BUT MADE IT A HORROR FILM!?

That’s the smart move today’s writer made. Like they always say, you know it’s a good idea when you read the logline and think, “Why didn’t I think of that?” Which is exactly what crossed my mind while reading Fiendish.

But are the knives out here? Or are they all those plastic fakey knives that retreat into the base when you stab someone?

35 year old Ben Vandererg is taking his new girlfriend, Angie, to his father’s mansion. His father, who’s in his 70s, ran a gigantic private equity firm and is worth 2 billion dollars. He’s invited all of his children home for the weekend, and the expectation is that he has cancer.

Once at the mansion we meet the rest of the family. There’s the Zak Efron like Colin, with his wife Ingrid. Colin has a mean streak he’s been keeping up since he was 5. Then we have daughter, Brie, who snorts a lot of cocaine. She shows up with her husband Rick, who’s described as, “a homeless man’s Patrick Bateman.” Completing the family is the weirdo son, Tobin.

Once at the house, they sit down for dinner and are finally joined by their father, as well as some sort of paranormal investigator woman named Joanna. The dad explains that a couple of months ago, when he was away on vacation, someone did……. THIS! He removes the rug to show them a giant pentagram shape carved into the wood floor.

It is his belief that this pentagram has opened a door to hell and a demon has entered the estate and is now haunting him. He knows it was one of his children who did this. So he gives them 24 hours to talk it out, figure out who the culprit is, and fess up. If they do this, the remaining innocent children still get their inheritance. If they don’t, all the money goes to charity.

Let the games begin.

The kids immediately think that their dad has gone crazy and their first order of business is to get some lawyers involved to ensure that their obviously insane father’s new will is eradicated. But the more they talk, the more secrets spill out, the most damning of which is their father’s involvement with a former maid who eventually killed herself. Could this maid be back from the dead to get her revenge? And if so, who has she brought with her?

Fiendish is a mixed bag of treats with a few tricks thrown in and also some toothbrushes and raisin packages. To be honest, I don’t know exactly what genre this is supposed to be. Is it a horror movie? A horror-comedy? Or a horror-spoof?

It starts off as a horror movie. That’s clear.

But then the family comes in and they’re a little bit funny.

And when we get to the end, we have this theatrical monologue about who the killer is and how their guilt was deduced that I, swear to god, could’ve been cut and pasted from a Scooby-Doo episode.

So I’m a little unsure of what I just read.

I will say that quite a few red flags popped up along the way. One of the things I’m super-wary of whenever I read a horror script are cliched images and cliched scenarios.

In Fiendish we get a person who pulls up to a house only to see a momentary skeletal face in the second floor window that quickly disappears. We get someone who keeps having random unprovoked nose bleeds. We have ominous whispers whenever anyone is alone. And at one point, I kid you not, we have a literal cat jump scare.

Screenwriters everywhere. I beg of you. Never. EVER. Write a cat jump scare into your script. It is LITERALLY the most cliched thing you can put in a horror movie.

There were other issues as well. This is a whodunnit without a killer. Because nobody’s been killed! So it takes a while to wrap your head around that.

Then we have this will deadline. If they don’t find the non-killer by midnight, the inheritance is left to charity instead of the family. Well, the midnight deadline passes. So I guess the characters don’t technically need to solve the mystery anymore? Yet we keep going.

From there, we’re trying to open up some demon porthole but it isn’t clear what we’re going to do once it’s open. Are we sending the ghost maid back there? There’s an implication that we might be traveling to the demon realm to kill the demon, Andromalius, on his own turf. However I thought that Andromalius was here, in the earth realm. So I’m not sure who you’re killing in the demon realm. Maybe Andromalius’s troublemaking brother, Corqualiqus? I hear Corqualiqus is sort of the Jake Paul of the demon realm so in the grand scheme of things, maybe that’s a good idea.

Sometimes we writers can twist our plots into such elaborate knots that it takes an enormous amount of effort to explain what’s happening. So let this be a reminder. You don’t want the reader to have to connect too many dots to figure out what’s going on. Because the reader never has as much information as you, the writer, has. And they haven’t read the script nearly as many times as you. So they’re going to be more confused. Which is why you should err on the side of simplicity, not complexity.

As I was putting this review together, I thought to myself, “Carson, aren’t you being too hard on this script? Is it really as problematic as you say?” And the answer is no, it isn’t.

I think that whenever I read a Black List script, though, I have an expectation. I expect the script to be better than solid. “Solid” is still a high bar to reach in screenwriting. You have to know how to construct characters, how to set up a story, how to keep that story moving, how to write entertaining scenes, how to elevate moments (as opposed to giving us the same old thing). So when the script only reaches that “solid” territory, I’m disappointed. I wanted more.

In regards to “write entertaining scenes” – that’s is a big one. And while I could talk for hours about what makes an entertaining scene, it boils down to creating scenes that are memorable. And there’s only one scene in here that’s memorable.

It occurs when Angie gets stuck in the service elevator in the middle of the night, and we watch as it creeps up, story by story, and she sees really terrifying things as she passes each floor. It’s an original scene. It’s a suspenseful scene. But more than anything, it’s a SITUATION. The character is trapped. We understand the rules (an elevator slowly moving up). The moment builds. It’s a smart and interesting construct for a scenario.

You need at least 4 or 5 of these scenes in a horror script. Not one.

I still have whiplash from Fiendish. It’s a decent screenplay. But I’m not sure it’s elevated enough to recommend. The writer did nail the concept though. Taking successful movies and adding horror twists is one of the best ways to come up with a good idea. Let’s see what non-horror concepts you can turn into horror ideas in the comments section.

There’s gotta be a horror version of Top Gun out there, right? You could probably sell that pitch tomorrow. Who’s going to come up with it?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I challenge all horror writers from this point forward – whenever you’re about to write a scare or a plot beat into your horror movie, ask yourself if you’ve seen it before. And if you have, YOU MUST DITCH THAT IDEA and use something else. Sure, I want to write some creepy person up in a window too. It’s a horror movie staple. BUT THAT DOESN’T MEAN YOU HAVE TO USE IT. Wouldn’t you rather be known as the person who came up with new exciting images? Not ones that have already been done to death? It takes more time to think of them, yes. But who the heck said writing a good screenplay was easy? Oh yeah, my fault, I did. :)

Sports movies are some of the hardest movies to make work because they’re so inherently cliched. You got some sports person, either an athlete or a coach or a GM, who’s an underdog in some sense, and then they fight to get to the top where they finally win the big game and HOORAY, we’re all happy.

In theory.

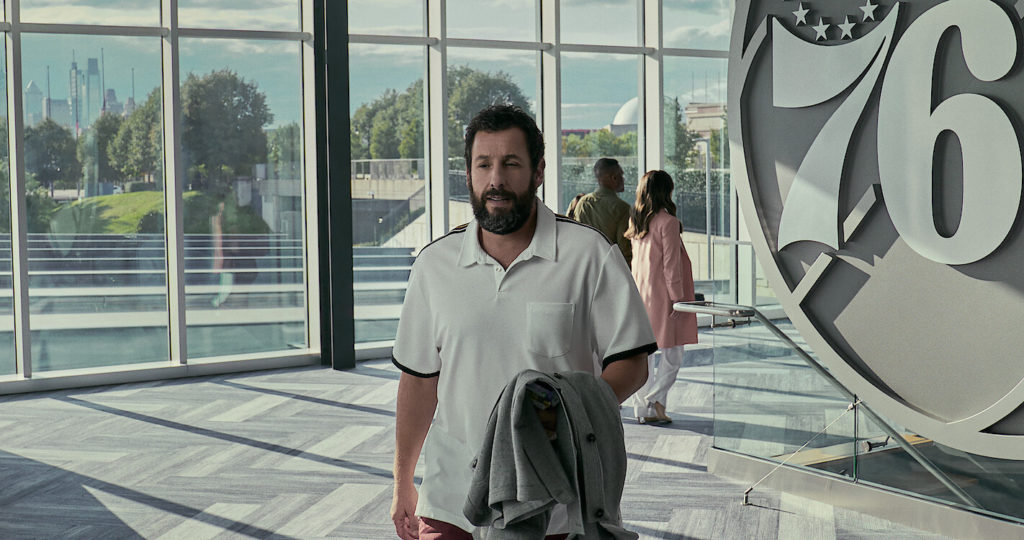

But in reality, whenever you see a sports movie on the docket, you feel like you’ve already seen it before. That was my issue with Hustle. I watched the trailer and I thought, “Okay, I definitely don’t have to see that movie.” Because it looked exactly like every other sports movie.

But I noticed a few of you talking about it in the comments and I thought, okay, I’ll give it a chance, fully expecting to tap out within 15 minutes.

But 15 minutes turned into 30, 30 to 60, and 60 until I reached the credits. The movie kept my attention the whole way through.

This made me stop, as it always does, and evaluate what happened to make me become so invested in this story. Cause I’m bored by most movies. Screenplays only have a handful of directions they can go. So it’s not hard to predict where they’re going.

“Hustle” was no exception. It went down the route I mostly knew it would go down. Yet I rooted for the characters. Yet I cared. Yet I was wondering how things would get resolved.

I can’t emphasize, enough, how important it is to answer this question. Because we are all working with a template that has been used, re-used, chewed up, spit out, regurgitated, reborn, used again, and used some more with every one of our screenplays. We are always fighting the battle of telling a story that’s already been told.

So if you can understand how a small percentage of these stories end up being good, you don’t have to reinvent the wheel every time you come up with a concept. You know that you can take a generic template and make it exciting.

Which is what Hustle did.

But how did it do it?

The answer is obvious yet complicated. What you first must accept is that there isn’t anything you can do plot wise that audiences haven’t seen before. Once every few years, somebody comes up with some whopper of a plot twist (Bruce Willis is a ghost!) that we didn’t see coming. But it’s hard to come up with truly shocking plot developments consistently.

I caught The Man From Toronto this weekend, which was a reasonably fun movie. But that movie literally hits every single Screenwriting 101 story beat that the screenwriting teachers say you have to hit. As a result, I will not remember any of it by the end of the month.

Luckily, there’s a way to overcome this issue.

You do it with your characters.

And the nice thing about this solution, is you really only have to do it with your hero.

If you can make us root for your hero, we will like your screenplay regardless of what you do with the plot. I know that sounds like a controversial statement but it really isn’t. It’s no different than if you meet a new friend or girlfriend or boyfriend who you really like. Do you need to travel to New York and take trips to the top of the Empire State Building to be happy around that person? No. You could literally lay on the couch for 10 straight hours eating Oreos and that would be enough.

Same deal here. Audiences are less concerned with experiencing some amazing plot when they love the main character. For them, just being around him and seeing what he’s going to do next is enough.

Now does that mean you shouldn’t try to write the best plot possible? Of course not. You want to enhance the experience of hanging out with that character as much as possible. But what it does mean is that you don’t have to worry as much that the predictability of your plot is going to be a problem.

Whenever I’m helping a screenwriter or developing a script with a screenwriter and we’re deep in the weeds and we’re worried it’s not working, I always step back and remind myself, “As long as we get the characters right, we’ll be okay.”

Now what I do I mean when I say “root for?” Because that’s kind of vague. The way I see it is, if you can make us feel like your hero is a) a real person, b) a person who is fighting to better themselves, and c) place them amongst unfavorable circumstances that we would like them to get out of, that’s enough to get us to root for someone. As is the case with any screenwriting advice, this won’t work all the time. There are certain stories that need you to adjust the formula. But this covers the bulk of protagonists you’ll be writing in your screenplays.

Which brings us to Stanley Sugarman, Adam Sandler’s scout character in “Hustle,” who I believe is one of the most well-crafted characters in sports history in so much as making the audience want to root for him. So let’s go over how they achieve this within the “root for” triumvirate.

By the way, if you haven’t seen the movie, it’s about a lifetime NBA scout (Stanley Sugarman) who’s running out of time to fulfill his dream of becoming an Assistant Coach who finds a once-in-a-lifetime prospect in Spain who he wants his team, the Philadelphia 76ers, to pick in the draft. When the brash new jerky Sixers president tells Stanley he’s not interested, Stanley quits the team and brings the player to the United States on his own dime in the hopes of getting him into the draft.

First off, Stanley feels like a real person. Nobody TELLS us that Stanley is a great scout. They SHOW us. They show him grinding. In Germany, in Spain, in China. Watching games in the farthest reaches of the world, looking for that one diamond in the rough.

We show him in airports, in hotels, coming back to Philadelphia, then going back out on the road again. Its’s an endless fruitless job. They show us his family – his wife, his daughter. They show him intelligently breaking down the top players he scouted in board room meetings. They have him saying jargon that only a NBA scouts would know.

All of this convinces us that Stanley is a REAL PERSON. If you don’t convince us of that, the other two things don’t work. We have to buy into this guy being real. If you get lazy and don’t do the work like Hustle did to show us that he’s really in this world, we’re turning your movie off at the 15 minute mark.

Next we have a person who’s fighting to better themselves. This is a key component to making us like a character. Cause we can have issues with people. We had issues with Louis Bloom. We had major issues with Arthur Fleck. But was there anybody else in the nightcrawler game who wanted to be better than Louis? While Arthur Fleck’s clown co-workers were fine playing kid’s parties, Arthur was busy planning his ascension in the stand-up comedy world.

Audiences like people who are trying to better their lives. Stanley Sugarman is 50 and he’s been doing this scouting thing his whole life. And he’s tired. He has every reason not to try. But he does. He keeps going out there, keeps grinding, keeps trying to find that one diamond.

And finally you have the negative circumstances surrounding your protagonist. You create negative circumstances because it gives the character somewhere to ascend to. If they’re already near the top, we don’t need to root that hard for them because they already have a good life.

Stanley is 50 years old and he’s still sleeping in Chinese hotels 20 hours away from his wife and daughter five nights a week. Talk about negative circumstances. (Spoiler) Right when Stanley gets his first official office with the Philadelphia Sixers, the owner who gave him the job dies the next day. Leaving his jerk son who doesn’t like Stanley to run the team. Talk about negative circumstances.

That simple one-two combo of making your hero someone with a big goal and then repeatedly punching them down, away from that goal, is like a screenwriting magic trick when you do it well. Because we like this guy. And we feel sorry for this guy. So of course we’re going to root for him.

Just to be clear, none of this means that, once you’ve done these things, you should phone your plot in. Because you’re never entirely sure if what you’ve done with your workers works. We can follow the rules and still write average characters, unfortunately. So you might as well try to make the rest of your script great as well. But getting that protagonist right solves so many potential issues down the road.

If you are someone who struggles with creating characters that readers root for, watch this movie. Even just watching the first act is enough. Cause that’s where you spend the bulk of your efforts on making the reader fall in love with your hero.

If you can write a character like Mikey, in “Red Rocket,” you’re in the discussion!

If you can write a character like Mikey, in “Red Rocket,” you’re in the discussion!

So, recently, a producer came to me saying he had a project he was trying to put together and needed a writer for it. This wasn’t some giant producer. But it was someone who could pay a writer real money. He hadn’t had a lot of success with literary agents, who he found pushed their weaker writers on him since he wasn’t A-List. Which is why he came to me. He knew I’d read more amateur screenwriters than probably anyone in town so, he figured, if there’s anyone who can find me a writer, it’d be Carson.

I get inquiries like this every couple of months and whenever I do, it helps me zone in on what it is that actually makes a good screenwriter. Because when you’re talking about screenwriters theoretically, there’s a leniency in your judgement. I want every screenwriter to succeed, especially the screenwriters on this site. So I see them through the lens of optimism and potential as opposed to reality.

But when someone’s paying money, all of that goes away. The last thing I want to do is refer a writer to someone, have that someone pay them a big check, only for the writer to deliver a weak script. Cause, of course, then I look bad.

So, all of a sudden, my eye becomes more astute. I’m able to see exactly what makes a screenwriter worthy of being a paid professional as I am literally recommending them to be paid. What is it I notice that prevents me from recommending someone and what is it I notice that leads to me endorsing them? That’s what I want to talk about today.

The first thing I notice is that the pool of writers I’d recommend to a producer is very small. We’re talking .5% of all the amateur writers I’ve read. Now before you freak out about that number, you have to understand that I’m not talking about recommending a writer to an agent here, of which the bar is more in the 3-5% range. I’m talking about actual money being transferred into the writer’s bank account. That’s a different conversation.

It’s the difference between potential and someone who’s got the goods. There are actually a handful of EXTREMELY TALENTED but raw screenwriters I know who I’d never recommend for this job because, to do this job, you have to understand the *craft* of screenwriting. You have to understand what the producer wants and have an actual game plan for putting it on the page.

These super-talented writers may have strong voices or a knack for great dialogue or a talent for taking stories to unexpected places. But many of those talents are connected to the freedom of constructing their own narrative. That approach doesn’t work as well when you’re adapting someone else’s idea.

To do that, you really need to understand structure. This is where the debate on whether there’s a “right” or a “wrong” way to write a screenplay leans towards “there is a right way.” Because the majority of Hollywood operates in the 3-Act Structure. Act 1, Act 2, Act 3. A beginning, a middle, an end. Setup, conflict, resolution. 25 pages, 50 pages, 25 pages. If you don’t understand that, it’s very hard to have a common language with your employer.

So that’s one of the first things I look for. I say to myself, “Do they understand the 3-Act Structure?” Cause if they don’t, it doesn’t matter what else the writer is good at, the script isn’t going to be paced well. It won’t have direction. It’ll feel like it’s wandering a lot. You got to have structure down, which, by the way, takes most writers about six scripts to feel comfortable with.

The next thing I think about is character. Specifically, have I read characters from this writer THAT I REMEMBER. Characters who jump off the page. Most screenplays – to be fair, even a lot of professional ones – give you characters who work for the story. But those characters don’t stick out. In other words, if you took the story away and just put that character in a bunch of random scenes, would they stick out? Would they be memorable?

For the majority of writers, the answer is no. They haven’t figured out how to do this yet. What do I mean by “memorable” character? Any character who feels larger than life via their charm, their pain, their eccentricities, their personality, their presence. Arthur Fleck, Louis Bloom, Cassandra in Promising Young Woman, Thor, Mad Max, Mikey in Red Rocket (guy in Ferris wheel at the top of this post), Mildred in Three Billboards. These are characters who rise above the page.

If you can pull these two things off, you are in the running. Cause these are the two most important things when it comes to nailing an assignment.

Dangling just below these two is dialogue. I’m not so much a “dialogue has to be great” guy as I am a “dialogue has to be good” guy. The reason for that is, great dialogue is rare. Name me three movies with great dialogue from last year. You probably can’t. Also, ironically, the better the dialogue is, the more subjective it becomes. That’s because flashier dialogue has more personality, and whenever personality is involved, some people hate that personality and some love it. Look no further than Juno’s dialogue as an example.

So I’m looking for dialogue that’s solid. There’s an honesty to it. There’s an effortlessness when it comes to covering exposition. The writer understands what dramatic irony is. They understand what subtext means. They also have the ability to add some extra flair to the dialogue to make it sound heightened, without it feeling try-hard.

If you can do those three things well – structure, character, dialogue – you are very much on my radar. I am now considering you for a paying job. Because now I know, at the very least, you are going to deliver a competent draft.

So, we’ve shrunk our pool of writers down to a small group. Who gets the job out of the remaining scribes?

Before I give you the general answer, I’ll give you the real-life one, which is that it depends on the project. If the project is dialogue heavy, I’ll go with the writer who writes the best dialogue. If it’s a comedy project, I’ll go with the funniest writer. If it’s a project that requires a certain weirdness, like The Lighthouse, then I’m recommending the writer with the most offbeat voice.

But if it’s a more generalized project, like, say, a biopic, I’m simply going with the best writer, or the writer I think has the most talent. Not only are they able to do all the things I listed above, but they also have that rare x-factor where they’re able to construct fictional stories in fresh and unexpected ways that make you feel things that you don’t feel when you’re reading everything else.

Another way to look at it is, somebody who’s the opposite of the average writer. The average screenwriter – someone who’s studied the craft and written more than six screenplays – does everything well, but nothing exceptionally.

If you want to become a paid screenwriter, you have to do at least one thing exceptionally. It can be that you write memorable characters, it can be that you write great dialogue, it can be that you’re so locked into the human condition that you can turn the average moviegoer into a slobbering pile of tears. But it’s gotta be something.

And part of the process of becoming a professional writer is identifying not necessarily what you *want* to be good at, but what you *are* good at, then writing scripts that allow you to showcase that talent. And then writing more of those scripts. And then writing more of them. Until you become an expert in that one specific area of writing. Because that means that when that type of project comes around, producers are going to think of you.

Finally, being the best at any aspect of writing is really hard. So there’s another option. Create your own future. After watching Tangerine this week (shot on an iPhone) and Cha Cha Real Smooth (made by a 22 year old), I’m reminded that sometimes it’s better to bring your own stuff to life than wait for someone else to anoint you. Because, do I think that Tangerine or Cha Cha Real Smooth would’ve lit the screenwriting world on fire? No, I don’t. Tangerine might’ve made The Black List. But Cha Cha Real Smooth wouldn’t have. So if those two were waiting for someone like me to say, “You’re the best of 10,000 writers,” they’d still be waiting. They went out and put those pages on the screen.

The point is, you have options. If nobody else believes in you, you can still succeed by believing in yourself. Whatever route you take, make sure to give it everything you’ve got. Cause I promise you, the competition is too stiff for any other approach.

Happy writing this weekend!

$100 OFF DEAL! – I’m giving $100 off two feature screenplay consultations this weekend. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with subject line: “100.” I give screenwriting consultations for every step of the process, whether it be loglines, e-mail queries, plot summaries, outlines, Zoom brainstorming sessions, first pages, first acts, pilots, features. If you’re wondering where your structure, or characters, or dialogue, stand, you can ask me to focus on them in your notes and I’ll be happy to assess them. E-mail me and let’s set something up!

Genre: Romantic Comedy

Premise: After Amanda is seemingly ghosted by the man of her dreams, she’s delighted to discover he’s actually been kidnapped — and takes it upon herself to be his rescuer, going on an adventure of epic proportions along the way.

About: This script finished with 9 votes on last year’s Black List. The writer has a small indie credit from 2014 but it’s safe to say that this is his true breakthrough in the business.

Writer: Dan Schoffer

Details: 104 pages

Is Anna Kendrick the only actress who can make this character likable?

Is Anna Kendrick the only actress who can make this character likable?

In a recent newsletter I shared a comedy idea with you called “Friend-Zoned” about a beautiful woman notorious for friend-zoning all the men in her orbit, who then falls for a studly new guy at work, only to get friend-zoned for the first time in her life.

I thought it was a funny idea and I liked the potential internal journey of the main character. It’s fun to watch someone high and mighty get their comeuppance. The only thing I was worried about was, would anybody actually like someone who spends all of her interactions with men emotionlessly crushing their dreams?

This script proved to me that my worries were justified.

26 year old first year lawyer Amanda Tinsely has gone out on 87 Tinder dates this year alone. In every single instance, she has ghosted the guy after the first date. Amanda sees this as a good thing. If she were to actually call the guy and reject him, he would have to feel the sting of her disinterest. In all these cases, it’s easier if they just keep texting without a response and eventually figure it out on their own.

Then one day Amanda’s walking around and she hears a guy whistle at her. Morphing into Captain Marvel mode, she immediately scolds the man. That is until she realizes he was whistling to retrieve his dog, Paw McCartney. Feeling dumb and also realizing just how hot this guy (Julian) is, Amanda does a 180, goes home with him, and they bang.

Amanda is soooooo very happy that she’s finally found a guy that she likes, but the next day at work she realizes that he still hasn’t texted her. So she texts him. But he doesn’t text back. Not later that night. Not the next day. Not all week! Amanda is devastated because SHE’S JUST BEEN GHOSTED.

Of course, Amanda can’t leave it at that. Their connection is too strong! So she does what any rational person would do, finds out where Julian lives and goes to his house. As she’s about to ring the doorbell, the neighbor informs her that Julian has been missing all week. Amanda is ecstatic! This means Julian didn’t ghost her.

Amanda uses her law firm connections to get access to a private investigator, Dean, only to find out that Dean is one of the 87 guys she went on a date with and ghosted! Dean agrees to see her again basically to tell her that she’s a bad person, but reluctantly gets hired by Amanda to find Julian.

Dean eventually locates Julian in Panama, of all places, potentially kidnapped by a powerful business woman who is trying to take over the country’s internet. Dean and Amanda then fly down to Panama, find the compound where Julian is being kept, and try to infiltrate it via one of his body guards. Using the only talent she has – getting matched on Tinder – Amanda is able to match with the businesswoman’s bodyguard, giving the two a direct opening to rescue Julian! But what happens when Dean starts to actually like Amanda? Will he convince her to leave Julian there?

Ghosted highlights one of the trickiest aspects of writing comedies.

Comedies are meant to make people laugh.

Comedies also need a well-rounded interesting protagonist to make us care enough about the journey where we can bother to laugh. You can’t laugh if you’re barely paying attention.

Thus is the need to create a main character with a flaw. That flaw is what allows us to feel that they’re a real person with a REAL change that needs to happen in their life.

Unfortunately, by definition, a flaw is negative. And a lot of negative flaws result in unlikable characters.

The challenge with comedy scripts is to make the main character’s flaw deep enough that they feel like a real person who needs change, but not so deep that we dislike them.

I don’t think that Ghosted achieved that goal.

We just don’t like Amanda. She’s acting high and mighty on all her dates. She ghosts everyone. The guy she does fall for is some perfect model whose only positive attribute is his acrobatic sexual prowess.

Why are we supposed to root for this girl again?

I think what this writer is hoping for is the same thing I was hoping for in Friend-Zoned, which is that we’d all enjoy watching a pompous main character get their just desserts. We’d enjoy seeing them suffer at their own game – the same formula that was utilized successfully in Groundhog Day.

Groundhog Day is an interesting example because the main character was *really* unlikable. Like a bona fide a-hole. But the reason why that movie was able to overcome that was that it put its main character through hell. At a certain point things got so bleak that all Phil wanted to do was kill himself.

At that point, how could we not root for him? We felt terrible for the guy.

But “hate me first, love me later” is an untraditional structural choice that’s difficult to pull off, especially in this day and age where people make their minds up faster, and once they do, they mentally check out.

Either way, Ghosted never gives us any reason to change our minds about Amanda. She gets bumped and bruised a bit in Panama. But, for the most part, she has the same attitude of “I’m the prize and everybody else needs to realize that.” Nobody’s going to get behind a character like that.

With that said, there are things that work about the script. The dialogue is very light and fun. The dialogue I enjoyed most was when people would tell Amanda she was an idiot, such as this scene where she’s trying to explain to a cop her connection to Julian…

And there was one really fun set piece where Dean sent Amanda off on a Tinder date with Hector, the bodyguard, with the instructions to drug his drink with a concoction that would force him to tell the truth so they could get answers on where Julian was located. But what Amanda didn’t know was that the drug “strips” she’d be using could be ingested through the skin. So she’d taken them out of their baggie and placed them in her bra. Once on her skin, they dissolved, and so instead of Hector telling the truth, Amanda starts telling it.

But the script fails one final test which is that it doesn’t convincingly show its main characters falling in love. If we’re to root for Amanda and Dean to get together at the end, you have to give us 2-3 genuine scenes in the second act where we see them connecting. If you don’t have those scenes, then the big flashy ending where the girl runs after the guy to tell him she likes him feels empty. Because we never saw any chemistry there to back up those supposed feelings.

Romantic comedies can be deceptively hard because there are all these little things that you have to get right. But I think creating a likable protagonist and giving us convincing moments where we can see our main characters falling for each other are obvious prerequisites. Ghosted needed to nail those two things in order to avoid getting ghosted but didn’t.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The Hector Tinder Date Set Piece is a great example of what all of you should be doing with your set pieces. You come up with a plan – in this case, drug Hector so he tells them the truth – and then make something completely unexpected happen instead. Here, Amanda gets drugged instead. This ‘flipping of the plan’ turns this scene into something completely unexpected. You rarely want things going according to plan in screenplays. The majority of the time, you want the plan to fall apart.

What I learned 2: I’m seeing more and more comedy/romantic comedy scripts include exotic locations due to Hollywood wanting bigger flashier comedies that can play outside of the U.S. The adventure aspect of the script gives it a broader appeal than if everything was set in New York.