Search Results for: mena

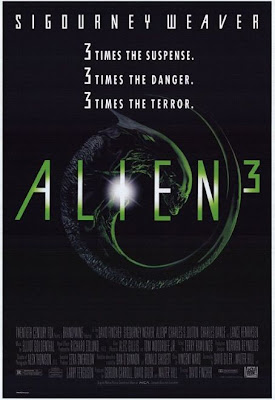

So last week I gave you ten screenwriting tips to take away from Aliens, one of the best sci-fi action films ever. This week, we’re looking at the sequel to Aliens, Alien 3, which a young David Fincher directed. Now originally, I wrote this long impassioned opening about how terribly directed this movie was. The setting was beyond boring. The casting was uninspired. For some reason Fincher had every character whispering to each other. I’ve since done some research and learned that Alien 3 had an extremely complicated development period even by Hollywood standards. 30-some takes were written over the course of six years and when they finally hit production, they were still rewriting the script. Fincher was so upset about the experience that he parted ways with the project and left the studio to cut the film. Does this mean I’m going to take it easy on the script? Hell no. They had six years to write this thing. They made the choice to go ahead with it before it was ready. Casablanca was rewritten during production, right? No, I’m not going to be easy on it because even with these excuses, Alien 3 is still terrible beyond comprehension. With that in mind, here are ten mistakes to avoid when writing your next screenplay.

PASSIVE STORY

You’ve heard about passive heroes a lot – characters who let everything come to them, who let outside forces dictate their actions instead of taking charge and doing it themselves? Well there’s another passive activity you want to avoid – passive storylines! Alien 3 spends the first half of its running time with absolutely NOTHING going on. Where is the goal? Where is the story? Where is the DESIRE from any of the characters (alien included!) to do ANYTHING?? It’s just a bunch of people sitting around with occasional cuts to an alien growing up. Contrast this with Aliens where there’s always a strong goal for the characters (go in and kill the aliens). Or even in the first Alien, which is closer in spirit to this one, the alien itself was active (searching out and killing its prey). Here, no one’s pursuing anyone. Even when they decide to catch the alien, they do it in a passive way (they try to lure him to a spot on the base – forcing them to run away from it the whole time). Reflecting on this film, I can’t remember a single active pursuit by anyone. This alone killed any chances the movie had of being good.

ACTING OUT OF CHARACTER

In the real world, people act out of character all the time. In the movies, the rules are different. If someone who’s perennially shy busts out the Dougie on the 3rd Street Promenade, the audience is going to be really confused (unless it’s properly set up of course). One of the quickest ways to lose a reader is to have your character act completely out of character, as is the case here with Ripley. Let’s recap, shall we? Ripley survives her entire crew being killed by a crazy ass alien. Ripley goes into cryo-sleep for 57 years. Ripley is asked to come help some marines dispose of some more aliens. She does, kicking ass and being one of the only survivors. She again goes into cryo-sleep. Her ship crash lands on a prison planet, and everyone onboard besides her dies, including the little girl she’s unofficially adopted as a daughter. After a few minutes of crying, what does she say to the big creepy ugly personality-less weird dude taking care of her? “Are you attracted to me?” Yes, all of a sudden Ripley wants to fuck!!!! Despite us not seeing Ripley have a single sexual urge for two movies, now she’s a nymphomaniac! Seriously, who the hell wrote this?

YOU WILL NEVER GET AWAY WITH LAZINESS

For some weird reason, certain writers believe they can skimp on the details and we’ll just go with it. We will not go with it. We will always spot when a writer is lazy. Let’s look at the prison here in Alien 3. This is supposed to be a maximum security prison right? So then why are there NO RULES!?? Why is there NO STRUCTURE!?? Prisoners can walk around wherever and whenever they want. There are no prison cells…IN A PRISON! There is no structure besides an occasional meal in the common area. It’s unclear who the warden is. It doesn’t even look like a prison. It looks like a series of interconnected tunnels. If you’re going to write a movie about a prison, learn how prisons operate so that your script will at least be somewhat plausible. Laziness gets you nowhere.

LOGIC MISTAKES EVERYWHERE

I’m always disappointed when writers ignore logic. But especially in a sci-fi movie. The rules are much more precarious in sci-fi because you’re already asking your audience to make a leap and believe in a world that doesn’t exist. Throwing a bunch of logic holes into that story is like shining multiple spotlights on the illusion. We are asked to believe, in Alien 3, that in a maximum security prison with the most lethal prisoners in the universe, that there isn’t a single weapon in the entire prison??? This is such a preposterous notion that it alone could be used as a legitimate excuse for hating the movie.

TRUST YOUR GUT

I have a theory I’ve formulated over time and I think it’s a solid one. When it comes to key decisions in your story, trust your gut. If your gut tells you it’s bad idea, it’s probably a bad idea. Even if it feels right from a logistical-standpoint. Even if it feels right from a character standpoint. If there’s that little voice in the back of your head saying, “This doesn’t feel right.” Trust it. To prove this theory, go back to all those reluctant choices you made in your previous screenplays. Chances are on an overwhelming percentage of them you turned out to be right. They didn’t work. I bring this up because while Ripley getting pregnant with an alien and having a special cross-species relationship with it may have sounded cool in the room, it’s one of those things that, at a gut level, you know isn’t right. Ignoring this gut feeling led to one of the dumber storylines we’ve seen in the franchise.

ALL THE CHARACTERS LOOK AND ACT EXACTLY THE SAME

There are a lot of reasons for you to differentiate your characters. One of the most important ones is that the more different your characters are, the more they bring out the differences in the other characters. If a person is nice, for example, we’ll obviously see that they’re nice. But we’ll see that niceness more clearly if we put them in a room with a mean person. Their qualities are exaggerated by being in proximity to their opposite. In Aliens, Burke’s sliminess is brought out in large part by what a good person Ripley is. In Alien 3, every single character looks the same and acts the same. They’re all a variation of annoyed, twitchy, and angry, except for maybe the doctor, who’s so boring in his own way that it doesn’t matter. You need variety in your characters. If you were to ask what’s the biggest reason for why Aliens is so great and Aliens 3 is so terrible, the unique cast of characters would likely come up as the top answer.

NO HUMOR

This is a common beginner mistake. Someone wants to make a dark film. So they make every single stinking frame as dark as humanly possible. Dumb move. Emotions are like anything in life. If you get too much of one, you’re going to get bored. I love cake. But that doesn’t mean I want to eat it three times a day. When it comes to emotions, you need to bring the audience to the other end of the spectrum every once in awhile to mix things up. Again, look at Aliens. There’s some bleak ass shit in that movie. But it’s peppered with a lot of humor (and plenty of hope as well). Alien 3 is one long bleak-fest. I counted a single joke, one joke!, in the entire movie (“No need to get sarcastic”). It could be as simple as adding a comedic relief character (Hudson) or throwing in a reasonable amount of gallows humor. Don’t think of it as selling out the darkness. Think of it as reminding the audience what darkness is.

IDENTIFY THE CENTRAL PROBLEMS – FIX THEM

At some point in the writing process, you should note the major problems in your script (the things that don’t quite make sense or aren’t yet working) and formulate a plan to fix them. Bad screenwriters allow many of these lingering issues to stay in the script, figuring they won’t be a big deal. If you aren’t striving for perfection, why even bother pursuing screenwriting? Let’s take a look at a really lazy mistake in Alien 3. In the final act, where they confront the alien, it’s established that the alien won’t hurt Ripley, because she’s impregnated with another alien. So let me get this straight. The only person on this entire base that we even halfway care about – your HERO no less – CAN’T BE HARMED BY THE ALIEN????? How stupid of a story decision is that? Identify your major problems and fix them. Or else you get ridiculous situations like this one.

WOE-IS-ME

Let me make something clear. Audiences hate woe-is-me characters. They hate them more than any other character you can possibly put in your screenplay. Whoever was dumb enough to turn Ripley from an active intelligent ass-kicking take-charge protagonist into a whispering, whiny, mousey annoying whisperer who can’t shut up about how awful she feels should never be allowed near a copy of Final Draft again. There are very VERY rare occasions where woe-is-me protagonists work (Mikey from Swingers comes to mind) but my suggestion would be to avoid them like the plague. The audience will hate your hero, and by association your movie.

BEWARE OF CLICHÉ/PREDICTABLE MOMENTS

Audiences are savvy. Many of them have seen enough television and film to have a pretty good idea of what’s going to happen next. However, if your script is packed with scenarios where the audience can predict EXACTLY what’s going to happen next, chances are you’re being too cliché and need to make a better choice. There’s a moment deep in Alien 3 where Ripley asks Rock (I don’t even know his character name so I’m using his real life one) to chop off her head because she’s pregnant with an alien. She turns away and puts her hands up on the bars, waiting for him to do it. There is then a 60 second build-up where he brings the axe back and prepares to kill her. Oh no! Is he going to do it??? I’d say of the 5 million people who saw this film, 4,986,000 knew Rock would deliberately swing and miss, making the loud dramatic “THONK” on the bars, we’d stay on Rock’s face so as to momentarily wonder if he’d killed her, we’d show that Ripley was indeed still alive, then give Rock a rah-rah speech about how much he needs her. What do you know? That’s exactly what happened! You can’t always avoid your audience being ahead of you, but with a little effort, you can avoid cliché moments and at least keep them guessing.

IN SUMMARY

I don’t know what else to say. I guess if there are great screenplays like American Beauty and Dogs Of Babel out there where every single choice the writer makes is perfect, there can also be screenplays where every single choice the writer makes is disastrous. Such is the unlucky distinction of Alien 3. But maybe it was a nice reminder to the studios that you can’t fake it. That even the death of some of your biggest franchises is one bad script away. I’ll finish this breakdown with another question for all you Alien nerds. To this day, I’m still confused about the Alien 3 trailer that came out promising aliens coming to earth. What the hell was that? Why would they play a trailer that had nothing to do with the movie? I guess it’s just one more nonsensical thing associated with this catastrophe of a film.

Whoa, I’m not usually nervous while writing up Scriptshadow posts but this one’s got me a little jittery. Outside of the prequels, I don’t think there’s been a more documented breakdown of a film’s failure to deliver on an audience’s expectations than that of Indiana Jones And The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull. The thing is, I didn’t participate in that documentation. There was something never quite right to me about a 65 year old Indiana Jones. This was a character built on his vitality, on his youth and strength, so to turn an Indiana Jones film into Space Cowboys 2: Let’s Laugh At The Old Guy, felt like a disaster in waiting.

This allowed me to approach Skull with super-low expectations, and ironically, enjoy the film for what it was – a sloppily constructed summer tentpole film. The movie was clunky and awkward and weird – like a lot of those films tend to be – and seemed to spend most of its running time trying to figure out what it wanted to be rather than just…be.

And I think that’s the ultimate failure of Indiana Jones 4. Clearly, Lucas and Spielberg wanted to make two different movies, and a handful of unfortunate writers were assembled to balance those opposing visions and turn them into a cohesive story.

Now it’s important to know that my goal here is not to rip this movie apart. Millions of internet nerds took care of that long ago. I want to identify the poor screenwriting choices Skull made so we can learn from them and avoid those mistakes in our own writing. So, I give you the opposite of my previous Raiders article: Ten screenwriting no-nos you can learn from Indiana Jones and The Kingdom of The Crystal Skull.

THE PROTAGONIST ISN’T ACTIVE

Remember Raiders of The Lost Ark? Remember my very first observation about that movie? Indiana Jones was ACTIVE! In the very first scene, the man is risking his life to secure a golden idol from a trap-filled cave with death at every corner. When he hears about the Ark’s possible resting place, he’s on the first plane to Nepal, obsessed with locating the mythical relic. In this film? You wanna know what happens in the first scene? Indy’s been captured. Indy is REACTING to everyone else. Indy is doing WHAT OTHERS TELL HIM TO DO. It sets the tone for who Indy will be for the next 2 hours (or is it 3 hours?). He will be a REACTIVE character. He will be following Mutt around on this quest for the crystal skull. And because someone else is driving the story besides our main character, everything seems…less important. Think long and hard if you want to have a reactive hero in your action script. Chances are, it ain’t going to work.

MOVIE TAKES FOREVER TO GET GOING

Remember how quickly Raiders moved? Remember how there wasn’t an ounce of fat on it? A big reason for that was that the story knew what it wanted to be so it was able to get there right away. 15 pages in (FIFTEEN PAGES!) we’re given our goal: Get the Ark Of The Covenant. Contrast that with the bumbling, stumbling, mumbling Skull. Do you know when the plot is revealed to us in this film? Page 30! That’s when Mutt tells Indy about the coded Mayan message. Do you know when we actually START our adventure? Page 38! That’s over 20 pages further along than when Raiders got going. And people wonder why Skull feels like it drags.

PLOT IS UNCLEAR

Clarity in your main character’s central objective is crucial to the audience’s enjoyment of the movie. It’s the key to everything else working in the script. If, for example, in Raiders, we didn’t know that Indiana was looking for the Ark, we wouldn’t have cared nearly as much as we did. Yet that’s exactly how Skull tells its story. We’re never exactly sure what we’re looking for. I mean, the title mentions a crystal skull, but we only find out about the skull once Indy and Mutt locate it. Then what’s the movie about? We’re never sure! Indy’s double-agent buddy mumbles something about a city of gold. Russian Psychic Chick talks about plugging the skull in somewhere. But all this jibber-jabber is incredibly vague and we’re constantly wondering what the endgame is. The point is, the audience is never clear what the characters are going after in Skull and the second we’re unclear about your characters’ objectives, your movie is dead.

DON’T BE TOO ‘WRITERLY’

Someone gave me a note on a script once that I’d never heard before, yet I understood exactly what he meant as soon as I read it. He said my scene was too “writerly”. It’s tricky to define this word, but essentially it’s when you’re too clever for you own good, when a scene seems original and interesting as you write it, but feels false when it’s read. The magnet bullet scene in the beginning of Indy 4 is a “writerly” scene. I’m sure it felt inventive when it was conceived. (“And, like, these bullets will be dancing down the warehouse and we’ll be like, ‘Where is it taking them???’”) But man does it feel awkward when you watch it. Another “writerly” moment is the “family holds hands on top of car with baby monitor to get the alien signal” scene in M. Night’s “Signs.” Sometimes we can fall so in love with our creativity, we can’t see the forest through the trees. Be aware of “writerly” scenes in your script.

DON’T PUT GAGS BEFORE YOUR STORY

The reason people got so worked up about the infamous “nuke the fridge” scene in Skull actually had nothing to do with nuking the fridge. The problem was that the scene shouldn’t have existed in the first place. We could’ve easily cut straight from the warehouse to Indy’s classroom. So why, then, was this scene included? Because Spielberg (or Lucas) liked the gag. That’s the only reason it was there. And boy did they pay the price for it, because by holding the movie up for an entire 8 minutes for a silly gag that added nothing to the story and did nothing to push the plot forward, it allowed the audience to focus their attention on the absurdity of surviving a nuclear blast in a fridge. Except in rare circumstances, avoid putting anything in your screenplay that isn’t pushing the plot forward. Didn’t Spielberg learn this after his buddy’s whole fish-dragon sequence in Phantom Menace?

FORCED PLOT POINTS

Don’t force unnatural plot points on your audience. After the opening warehouse sequence, the FBI – for no logical reason – thinks Indy is a commie, which leads to an embarrassingly forced scene where Indy gets fired. If you need your hero to get fired for story purposes, GIVE US A REALISTIC REASON THEY’D BE FIRED. Don’t make up something that takes us out of the story. I’d easily buy Indiana Jones being forced into retirement because of his age (he is 65). Any time you insert a nonsensical plot piont in your story, you run the risk of breaking the audience’s suspension of disbelief. Keeping that suspension intact is essential to making the story work.

UNCLEAR ACTION SCENES

Remember how much I praised Raiders Of The Lost Ark’s action scenes. Do you remember why? Because the main character always had a clear objective! Here, action scenes are given out like past due Halloween Candy, none more random than the university motorcycle chase. On the one hand, we know Indy and Mutt are trying to escape. The problem is, we don’t know why. What do these men want? Are they killers? Are they kidnappers? Do they want the scribbled note? Do they want Jones to explain it? Is it okay to kill Indy and Mutt? Or do they need them alive? There’s an overwhelming lack of clarity in this chase, which is why it feels so pointless. To make an action scene work, make sure everyone’s motivation in the scene is clear. (as a side note: Compare how much Indiana is BEING CHASED in Skull to how much he was DOING THE CHASING in Raiders. Coincidence that the first film was more fun and exciting? Hmmm…)

EXPOSITION EXPOSITION EXPOSITION

I’m starting to think Christopher Nolan did a rewrite on Indiana Jones 4. The exposition in this script is so abundant and so lazy it’s embarrassing. How many pure exposition scenes do you remember in Raiders? Me? I remember one. The scene where they discuss going after the Ark. Here we have an exposition scene with the CIA agents after the Nuke The Fridge scene. We have one with Mutt in the cafe. We have another Mutt-Indy exposition scene after the motorcycle chase. Then we fly to the Amazon and get ANOTHER exposition/backstory scene as Indy and Mutt walk through the market. We then have another exposition scene down in the haunted cave. Usually when you have that much explaining to do in your story, it’s because you haven’t figured everything out beforehand, and are therefore forced to work it out during your script, resulting in…..you guessed: lazy overly abundant exposition.

LONG SCENES IN ROOMS IN ACTION MOVIES

This is an action movie. So can someone please tell me why there is a 15 minute scene in the middle of the movie that takes place in a tent? Putting your characters in a room for too long in any movie is a bad idea. But in an action movie, where the audience is expecting…ACTION?, a scene like this is deadly. And here’s the thing. WE DON’T EVEN KNOW WHAT THE PURPOSE OF THIS SCENE IS! CIA Double Agent Buddy comes in and yells at Indy about a city of gold or something. Russian Chick comes in afterwards (as if she was waiting for her turn – GOD THE LAZINESS IN THIS SCRIPT!) and tries to read Indy’s mind for…some reason. Then Rickshaw Jim The Mental Moron shows up to write something on a piece of paper. How many “people in a room” scenes were in Indy that went over 3 minutes? The Marion-Belloq scene maybe. But that scene actually had a purpose. Marion was trying to escape. This is just a big fat tent of non-stop exposition (and what’s even more baffling is that the point of exposition is to CLARIFY things for the audience. After this scene, we’re actually MORE confused than we were before it). The lesson here? Don’t place your action hero in a room for any extended period of time unless there’s a strong plot-related reason for it.

NEVER MAKE THINGS CONVENIENT OR EASY FOR YOUR CHARACTERS

You remember the truck chase in Raiders? Remember how Indy had to use every ounce of strength, every punch, every kick, every last brain cell (cleverly sliding underneath the truck so as not to get smushed). He worked his tail off to get control of that truck. Here? Everything, from fights to escapes are just HANDED OUT to our heroes. That 15 minute long tent scene I mentioned above? How did they get away? Shia KNOCKS OVER A TABLE! Are you kidding me? When Indy is shot into the desert with the Russian after the warehouse scene, what happens when he comes to a stop? The Russian has fallen asleep! In the back of the truck arguing with Marion? Indy KICKS the guard in the ass when he’s not looking, resulting in him passing out! But the worst is when our characters accidentally fall into a river, get dumped down three successive waterfalls, and miraculously happen to end up RIGHT IN FRONT OF THE MYSTERIOUS CAVE THEY’VE BEEN LOOKING FOR! This is a huge reason why the Indy 4 experience feels so unsatisfying. Our characters don’t earn anything. They’re HANDED everything. So please, always make things difficult for you characters. And make sure they earn their way.

So, I guess the only question left to ask is…did Indy 4 do anything right? Barely. While the goals are weak, the stakes are low, the urgency isn’t there, the plot’s unclear, there’s too much exposition, the villains suck, and the characters are barely developed, I will admit that the last 40 minutes or so were pretty exciting. Unfortunately, the reason for this had little to do with the screenplay. We, as an audience, simply knew that the story was coming to an end, and this finality, while artificially generated, gave the story some much-needed purpose. I’m disappointed with Spielberg and Lucas. I understand that there were a lot of factors at play in making this movie happen, but you’d think they’d at least put together a COMPREHENSIBLE screenplay, one where we actually understood what was going on. For some odd reason, when directors get older, they get lazier, and we got the result of that laziness here. Oh well, I heard they’re making a fifth film. Maybe someone actually plans to write a screenplay for that one?

As frequent readers of the site know, one of the more insightful commenters on Scriptshadow is Filmwonk (now Bohdicat). I don’t always have time to read through every comment, but he’s one commenter I always check in on, as he often points out stuff that I either didn’t have the time to get into or didn’t even think of altogether. So today Filmwonk is getting the full red carpet treatment and not just giving us a comment, but writing an entire review. Make sure to make him feel welcome.

Genre: Drama

Premise: A young boy goes on a journey through New York City to find the truth about how his father, who disappeared in 9/11, died.

About: Based on the book by Jonathan Safran Foer, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close was adapted by Eric Roth, who won the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay for Forrest Gump

in 1994. He also co-wrote the screenplays for The Insider

(1999), Munich

(2005), and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

(2008), all of which were nominated for Oscars. Roth was born in New York to a studio executive and a film producer. He got his masters from UCLA Film School. In a side note about Roth, he is one of the unfortunate group of investors in the Madoff Ponzi scheme, and has admitted to losing all of his retirement money in the scam. Tom Hanks and Sandra Bullock star in “Extremely Loud.” 12 year old Thomas Horn, who won Jeopardy Kids Week in 2010, will be playing Oskar.

Writer: Eric Roth (based on the novel by Jonathan Safran Foer)

Details: 137 pages – March 17, 2010 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Eric Roth is very much an anomaly in screenwriting circles. He more or less does things his own way and doesn’t subscribe to fancy-schmancy screenwriting theory. He simply sits down and writes what comes to mind. Once asked what a writer should do if they hit writer’s block, Roth unassumingly offered, “Change the weather in the scene. That’s what I do.”

Not exactly shocking. Roth’s adaptation of Forrest Gump bucks numerous screenwriting trends, and you’d be hard pressed to find much structure in Benjamin Button. This makes him a hero to some and a hack to others. The “do it yourselfers” love that they can point to a successful screenwriter who ignores convention. The “structuralists” argue that that’s the reason why his stories are all over the place.

I’ll never forget listening to an interview with Roth where he was asked why we hadn’t seen any spec screenplays from him. Roth was genuinely confused by the term. “Spec?” The interviewer actually had to explain what a spec screenplay was to Roth. He had no idea. After being told what it was, he explained that he had been paid to write a script right out of UCLA and has been working ever since. Eric Roth has never worked on an idea of his own. Make of that what you will.

Oskar Schell is a 10 year old boy who wishes his anus could talk. In other words, Oskar’s weird. He’s the kid who gets picked on at school, the guy snorting up jello through a straw. He’s a loner through and through.

Oskar’s best friend was actually his father. “Was” because his father was one of those unfortunate souls who died in the twin towers on 9/11. Now Oskar, his mother, and his grandmother (who lives in the adjacent building and who Oskar communicates with via walkie-talkie) are taking it one day at time, trying to make sense of how and why this happened.

Oskar, in particular, is devastated by his father’s absence, to the point where he combs international websites with videos of people jumping out of the towers, hoping he can break through the blurry pixelated dots to locate his father. Oskar needs to know how his father died that day so he can stop inventing his death. He needs closure.

One day, Oskar finds an old vase in his mother’s closet and accidentally breaks it, only to find a key inside accompanied by a letter to someone named “Black.” Believing that this key will open something that sheds light on that fateful day, Oskar plans to visit all 500 Blacks in New York City, to find out which one this envelope belongs to. If he can get a couple visits in every week, it should only take a few years.

During this time, Oskar meets his grandmother’s mystery tenant, an old man who can no longer speak. Oskar’s put off by his weirdness, but it’s not like he’s breaking any Facebook friend records, so he asks him to join him on his journey, and “The Renter” (as we come to know him) accepts the invitation.

In the meantime, Oskar has to come up with clever ways to escape his house without his mom finding out that he’s running around New York. The relationship between the two is strained at best. They always got along, but the death of Oskar’s father exposed that the link between them was bridged by him, and that without that bridge, they have nothing to talk about.

Oskar meets tons of characters along the way, including a guard who works at the Statue Of Liberty and lets him come up and look out at the city. But most of his search is met with shrugged shoulders and apologetic smiles. Despite Oskar looking for some grand answer to it all, he may have to accept that the answer may never come.

It’s rare that I just get to talk about how a script affected me b/c it’s rare that a writer is so good that they can make me forget I’m reading a story. But this script did it. In a lot of ways it reminded me of when I read The Social Network, where I just forgot about form and structure and character and got transported into another universe via Roth’s wizardry.

Roth has a strange way of writing that I can’t quite put my finger on, but it’s its singular and unique and when you’re reading him, you go with it. Maybe it’s because he ignores convention. I don’t know. But there’s some really heavy stuff here that Roth has to sell and you never once question it.

Now make no mistake, there are some key things in place to make this story work. First and foremost is the character goal driving the action. Oskar is trying to find out what this key opens, and the connection he has with his father, shown through flashbacks and voice over, makes that goal extremely strong. I mean, I don’t know if I’ve felt this much love between two characters in a screenplay before.

Also, Oskar is the ultimate underdog. He’s a 10 year old kid with no friends who lost the most important person in his life. I mean who’s not going to root for this guy? (Note that Roth’s other most popular character, Forrest Gump, was also one of the biggest underdogs in cinema history).

But it’s the details and the crushing scenes in this screenplay that will leave you thinking about “Extremely Loud” long after you’ve finished it. (Spoilers) First and foremost the final answering machine message scene. I mean, I can’t remember the last time I felt so devastated reading something. The explanation of what happened on that last call? Grab your Kleenex girls AND boys, as you’re going to need it.

And rewinding his father’s “possible” jump from the towers so that he’s going back up into the building instead of falling down? I mean wow. I needed to wipe away some man-tears after that one.

On a lighter note, one of the nice touches here is being able to see what Oskar imagines. The trailer on this movie is going to be phenomenal. We’re going to have helicopters carrying the world’s biggest blanket, dropping it on the twin towers. We’re going to have thousands of coffins with rockets attached to them shooting up into the sky. We’re going to have a half-man/half-robot waiting to talk to Oskar. We’re going to have the “Sixth Borough” out on its own island next to Manhattan. The imagination in this story is incredible, and you really feel like you’re being taken into another world with every page.

This is easily the best thing about 9/11 that I’ve ever read. Probably the best decision Roth (or Foer) made was installing as much humor as there is here – and there’s a lot. Cause the truth is, people are tired of how emotionally draining 9/11 is. They see it and they just want to escape. But Oskar’s view of the world is so funny that this devastating tale is bearable – even enjoyable. And somehow – I’m still not sure how Roth does it – it never feels false. Everyone says “Don’t do voice over. Don’t do voice over.” But man, for writers who know what they’re doing, it can be the most powerful part of a screenplay – as some of Oskar’s musings in this story are.

So was it perfect? No, and I think that’s because this is an early draft. This is 137 pages long and it feels like it. I think Roth gets a little carried away with giving us the father’s backstory. I mean, there are some great moments in there. There’s just too much of it. I liked how we’d get a flashback scene with them every 20 pages or so to remind us what Oskar was fighting for. But right now there are like 20 scenes with the dad, and I think that can easily be cut in half. For this reason, the middle act drags until The Renter shows up.

Also, the mom storyline needs to be fleshed out and better defined. We know these two don’t get along, but we’re not exactly sure why. So their eventual reconciliation doesn’t have nearly the punch that it should have.

There were a few other things that bothered me. Roth can get a little long-winded at times. But the key here is that this script made me feel something. It’s hard to finish this screenplay and not feel affected in some way. Reading through so many average scripts, I sometimes forget how hard that is to do. Someone else told me that this script makes Extremely Loud a front-runner for an Oscar in 2012. I don’t know if I’d go that far but it certainly has the seeds to grow into something great.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When comparing three of Roth’s most high-profile scripts, something sticks out. The combination of a heavy underdog and a voice over is a powerful one if you have the skills to pull it off. The underdog thing is obvious. Everyone roots for an underdog. But the additional voice over takes that connection between us to a new level. Because the main character is talking to us, we feel like we know him, and you’re always more likely to root for people you know. This approach was used to perfection in both this script and Forrest Gump. Contrast that with Benjamin Button, which was a good but not great film. It had neither. Benjamin was sort of an underdog, but not really, as he basically grew into a handsome young man. Also (if my memory serves me correctly) it was Cate Blanchett who did the voice over, not our hero. Are these the reasons Button is not as memorable as these two stories? I don’t know. But it’s certainly worth noting.

Hip Hip Hooray! Oscar nominations day. Maybe I’ll get to my thoughts on that later in the week. As of now, Article Thursday has been moved up to today, and Thursday will become a review day. Also, I found a new draft of Dibbuk Box, so I decided to do something unprecedented: go back and remix my review. So if you want to see my review for the newest draft of Dibbuk Box, head back to yesterday’s review now. Now, it’s time to talk about the increasingly strange behavior of Kevin Smith.

What a strange day Monday was. I woke up and every single site I went to had some blogger ranting about how Kevin Smith had become the anti-Christ. At first I thought they were part of a viral marketing campaign for Smith’s new religious-themed horror film, but no, everybody seemed to be genuinely upset, though it was hard to figure out why. After digging around (and reading through 100-something tweets on Smith’s Twitter feed) I finally put it together.

To summarize it, Smith previewed his long in development horror film, Red State, at Sundance Sunday night. Apparently, he’d told the public for weeks that he would have a live auction for the movie after the screening. So all the major indie companies sent their people there to potentially bid for the film. Except afterwards, Smith went on a 25 minute rant (or so we were told – the actual footage is only semi-ranty) telling those very people that they sucked and he was tired of them stealing his money so they could suck his dick. He then proceeded to “sell” the movie to himself, subsequently pissing off a lot of distributors who could’ve used that time to target other Sundance material.

He then announced he’d be taking Red State on tour, one city at a time, and charging $70/ticket (presumably each screening would end with one of Smith’s famous extensive Q&As – so the cost would cover more than the actual film). Smith’s argument was that this old model of marketing movies, where you spend four times the budget of your film on advertising, forcing you to make five times what your film cost just to break even, was ridiculous, and he wanted to try something new.

So instead of traditional advertising, Smith was going to utilize the power of his Podcast and Twitter feed (which has over 1 million followers) to let everyone know where the film was playing and how to buy tickets. After the tour, he’d release the film more traditionally, but with himself distributing the film instead of some big money-sucking distribution company, giving theaters more lucrative terms as an incentive to work with him.

Now I know this isn’t technically connected to screenwriting, but it kind of is. People with 1 million dedicated “can contact them at any time” followers simply weren’t around two years ago. That gives a ton of power to the individual, whereas before the individual had to depend almost exclusively on the company who financed his film. It’s a different ballgame and it might be time to start thinking about things differently. To think that the old model is going to transfer over seamlessly in this ever-changing world of social media is kind of silly.

With guys like Ed Burns foregoing traditional distribution and selling his movie directly on Itunes (where we’ll likely be watching all of our rented films in two years) so that he could retain ownership of his film, rather than hand it over to some prodco, has both its pros and cons. You’re not going to get that big marketing push, and thus your movie won’t be grossing nearly as much money, but you’ll be receiving some hefty royalties from being the sole owner of your film for quite some time.

Back in the days of video stores (I can’t believe I’m saying that – “Back in the days of video stores”), where shelf space was limited, you wouldn’t have thought of that. Not having that juicy “Miramax” or “Lionsgate” tag on your film would keep corporate-minded Blockbuster from even glancing at your film. But a virtual porthole, such as Itunes or Netflix, where the system is intelligent enough to know which movies you like and recommend them to you, makes those companies excited about a small movie owned exclusively by Ed Burns. It doesn’t cost them anything to throw it up there, and targeted recommendations means people will keep watching it.

At some point I expect this to trickle down to the development stage. If you developed your script openly, providing numerous drafts on the internet and encouraged feedback from fans, it’s an easy way to build awareness for your film (not to mention improve your script) and thus create anticipation throughout the development process. A case can be made that the leaked scripts for Inglorious Basterds and Avatar helped make those films what they were, and I would anticipate that same kind of buzz would happen with any filmmaker who has a built-in fanbase. I know some form of this is going to happen soon. I’m just not sure which major name is going to do it first.

So I’m really interested in what happens here with Smith. What sucks, and what’s turning out to be a distracting factor in this giant experiment, is that Smith may be heading off to Crazy Land. The guy is curling himself up into a cocoon of safety in order to protect himself from any sort of negative reaction whatsoever. First he takes on critics for hating a movie that was truly awful and says he’s not going to screen his movies for critics anymore. And now he’s giving a big fat middle finger to studios and production companies, which is allowing him to try this unique experiment, but creating an unhealthy amount of insulation in the process.

What he doesn’t realize, is that he’s effectively becoming the low-budget version of George Lucas. Just make movies in his own back yard and nobody’s allowed to tell him if they’re any good or not. This is the absolute worst way you can approach writing, and almost always leads to subpar work. If you have any doubt about that, go read The Phantom Menace.

It’s a weird scenario, and I don’t know if Smith’s post-modern Howard Huges-like behavior is going to get in the way of determining whether this is a viable option or not. Which sucks, because if it does work, it could be a game-changer. It could give birth to an entirely new generation of writer-directors, guys like Gareth Edwards and Neil Bloomkamp, who have a unique voice and realize that with emerging technology, they can make their movies on the cheap and distribute them outside the studio system, building followers on social media outlets through teaser scenes, short films, and word of mouth, then use those outlets to directly advertise screenings, whether they be in real theaters or online.

I think what Smith is doing is cool. I’m just worried that his questionable red state of mind may screw up the test. What do you think?