Search Results for: mena

Sunday Book Review is BACK! Watch Scriptshadow on Sundays for book reviews by contributor Michael Stark. We try to find books that haven’t been purchased or developed yet that producers might find interesting. Here’s Stark with Berlin Noir.

Genre: Detective / Mystery

About: Bernie Gunther, a hardboiled gumshoe working 1930’s Berlin.

Writer: Philip Karr – Best selling author of high brow historical fiction, now penning the über popular children’s series, Children of The Lamp.

Staus: ??? I’ve read that the film rights to all his books have been snapped up, but can’t find anything current. Readers please chime in.

Welcome back to another sporadic, Sunday Scriptshadow book review, where if we ran a film studio, there would be an immediate moratorium on sequels, remakes, reboots and board game adaptations; Carla Gugino would be in practically everything we shot and our favorite books would finally, finally, finally be churned into movies.

Yes, our little fantasy movie studio would probably go broke pretty fast, but at least it got us out of the house. I’d be fun to start every day like the long tracking shot that opens the Player. And, well, that, and the Carla Gugino thing.

Okay, before the main attraction, here’s a little something from the Minister of Propaganda to get you into the proper wild-goose-stepping mood:

Long time reader, Jean, recommended we take a look at Philip Kerr’s Berlin Noir, a series of detective novels set in Nazi era Germany. Sounded right up my Nightmare Alley, so I gave the first of the lot, March Violets a thumb through. And, great-shades-of-my-father’s-bad-memory-must’ve–been-passed-down-one-or two-generations-Old-Testament-style, I immediately recalled why it sounded so familiar. I had read it when it first came out twenty years ago! Didn’t know Kerr had written any sequels, so I’ve been noshing on pig’s knuckles and totally absorbed in all things Bernie Gunther the past few weeks.

So, why would these novels make a great damn movie or BBC or HBO TV series? Location! Location! Location!

Take Philip Marlow and stick him in a decadent Otto Dix drawing of pre war Berlin. If you like your detective fiction dark, you can’t get much darker than this time period when life even for the uncircumcised wasn’t exactly a cabaret.

The seven Gunther novels span from Hitler’s rise in 1936 to 1950’s Cuba. It’s an extensive, well-researched scope. Sort of reminds me of Martin Cruz Smith’s Arkady Renko, who sees his mother Russia change so drastically while he’s on the beat and Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins, who also lives through and thus provides commentary on the sweeping social changes around his homebase of Los Angeles.

Like most traditional gumshoes, Gunther hasn’t lost his tough-guy’s sense of humor even as the Nazis’ atrocities spill across the country. Perhaps, it’s the one thing they can’t take from him. An ex-policeman, he was famous for catching Gormann, the strangler, but left the force before he was squeezed out. Seems our Bernie had little interest in joining the National Socialists, pretty much career suicide at the time.

He becomes a P.I., specializing in missing persons, which means some brisk business, cause a helluva lot of people are disappearing around Hitler’s Berlin. Bernie isn’t an anti-Semite (would we like him if he were?) and most of his clientele are Jewish, desperate souls looking for their forced disappeared loved-ones.

Kerr doesn’t break from the literary shamus tradition of the hard drinking, chick magnetizing detective taking two cases, which shall at some point intertwine. In March Violets, Gunther is hired by industrialist, Hermann Six, to find out who murdered his daughter and son-in-law, burned down their house and took off with the cluster of diamonds in their safe.

This case will criss cross with an even more famous client hiring him, Hermann Goering, who is looking for a missing informant. On a side note, we learn the Nazi also has a penchant for lion cubs and the novels of Dashiell Hammett. “He’s an American,” Goering says. “But I think he’s wonderful.”

The case becomes even more complex as Gunther discovers that Six’s son-in-law was working for the SS and that his safe contained papers that some very senior officials need to get their paws on. This leads our gumshoe further down the slippery cesspools of Nazi society, ending up in Dachau itself.

Kerr sets the book during the Olympics, giving the city a temporary facelift for the tourists. Still, the menacing underbelly is everywhere you look – the corruption, the seedy night clubs, the new autobahn that will make invasion of neighboring countries that much easier and the violent pressure cooker of anti-Semitism that’s just about to explode into an all out Kristallnacht.

The next book, The Pale Criminal, is my favorite so far of the series. Bernie is hired by a rich publisher to find out who is blackmailing her about her son’s homosexuality. Gunther, is blackmailed himself by the SS, forced to rejoin the police and lead the search for a serial killer targeting young, blond, totally Arian, German girls.

Like before, his cases will criss cross, revealing the rather sadistic, political agenda behind these murders and how it all ties in with the Nazi’s Final Solution.

A German Requiem takes ten years later and life in Post War Berlin isn’t much of an improvement under the Russians. With a hat tipped to The Third Man, Bernie travels to Vienna to help a former colleague (A Harry Lime leagued black marketer) accused of killing an American soldier.

“A good story cannot be devised it has to be distilled.” — Raymond Chandler

While I’d love to see a big screen adaptation of all these books, the way to go may be a cable series. I’d be afraid that too much of the distillation, atmosphere and historical research would get excised cause of running time. Berlin Noir is a perfect hybrid of PBS’s Mystery, TMC and the History Channel. If Kerr’s eye for detail can be correctly caught on camera, I think you’ll have an intriguing show. I’d just watch it for the angels – I mean devils – in the architecture.

.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[] worth the read

[X] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned:

“Everything can be taken from a man or a woman but one thing: the last of human freedoms to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way. “– Viktor Frankl, Holocaust Survivor and Psychiatrist

Bernie Gunther is made of some pretty strong stock, surviving the battlefield, the loss of loved ones, a stint in a concentration camp and time as a POW in a Russian prison camp.

He was world weary and cynical to start with, but after everything he’s been through, he still sees every case to its conclusion. And, he still remains a decent man — the ultimate good German.

How strong is your protagonist’s resolve? After reading Philip Kerr’s trilogy, I started questioning my own.

Stark’s further rants and ramblings can be followed in his blog: www.michaelbstark.blogspot.com

Welcome to another week of Scriptshadow. This week, we have two mega-geek scripts we’re reviewing. The first is Peach Trees, the Judge Dredd project, which Roger reviews today. The second is a reimagining/sequel to a popular franchise from the past, a script that’s been around for a decade and is beloved by many. Well, I’ll just say right now that I have no idea why anyone would love this script. I was bored out of my mind. I’ll also be reviewing two low profile recent spec sales, both of which were quite good. And since it’s the last Friday of the month, that means Amateur Friday Review! I just picked out the script this morning so we’ll have to see if it’s any good. Right now, here’s ROGER with his review of the next Judge Dredd project.

Genre: Science-Fiction, Action

Premise: When Judge Dredd arrives with rookie Cassandra Anderson to investigate a trio of murders at high-rise called slum Peach Trees, a drug lord puts Peach Trees on nuclear lockdown and the Judges are trapped inside, hunted by the entire populace. The Judges must choose between escaping the building, or ascending two-hundred stories to prove the drug lord guilty and execute her.

About: Alex Garland (The Beach, 28 Days Later, Sunshine) writes this adaptation to the popular AD 2000 comic strip. Pete Travis (Vantage Point) is set to direct for DNA Films. Karl Urban will star. Judge Dredd was named the seventh greatest comic character by Empire Magazine, and in Britain, he’s certainly the most well-known.

Writer: Alex Garland

“Peach Trees. This is Ma-Ma. Somewhere in this block are two Judges. I want them dead. And until I get what I want, the block is locked down. All Clan, every level, hunt the Judges down. Everyone else, clear the corridors and stay the fuck out of our way until the shooting stops. If I hear about anyone helping the Judges, I’ll kill them and the next generation of their family.”

Peach Trees is the high-rise Judge Dredd becomes trapped in, a mega-slum with a population of a hundred thousand people that are either trying to kill or hide from the iconic character as he ascends two-hundred stories to prove a drug lord guilty and execute her.

It’s a plot stripped of any supercilious details that’s less Hollywood and more 2000 AD, a simple framework that possesses the brilliance of taking a well-known comic book hero and placing him inside a contained thriller.

It’s like taking Batman and putting him in Die Hard.

I remember the 1995 Judge Dredd movie.

While not a reader of the British comic strip, even I could tell that something was amiss. The tone was all over the place. Here was a simple character that was supposed to be a faceless personification of justice, but this personification has Rob Schneider as a sidekick and Sylvester Stallone as a face. Stallone is quoted as saying, “It didn’t live up to what it could have been. It probably should have been much more comic, really humorous, and fun. What I learned out of that experience was that we shouldn’t have tried to make it Hamlet; it’s more Hamlet and Eggs…”

While I don’t agree that it should have been more comic (Sorry, I can only stand one Rob Schneider in a movie), I do think Stallone had a point. The ambition and scale of the plot does not serve the character. A story that is supposed to be about a futuristic gunslinger whom possesses no sympathy for either criminal or victim is lost in a framework that somehow includes cloning, the Hero’s Journey, the power struggles of a dysfunctional family, cannibals and Sly unintentionally but comically screaming, “I am the Law!”

There was plenty of humor, but not enough, I dunno, carnage.

It wasn’t visceral.

I suppose the idea of a Judge trying to clear his name with the law can make for interesting conflict, but I don’t want to watch court scenes.

I want to watch Judge Dredd shoot bad guys with his Lawgiver Gun.

Wait. I don’t know anything about Judge Dredd or Mega City One. Does Alex Garland tell an origin story?

Nope.

And, that’s what makes “Peach Trees” so refreshing.

All you need to know is that it’s the future, and that there’s a guy who will shoot bullets through civilians (endangering them, but not killing them) to execute criminals.

Mega City One is the last outpost of civilization in post-apocalyptic America. It’s a series of mega blocks, monolithic high-rises that serve as their own self-contained towns, stretching from Boston to Washington. Skyscrapers are the low-rise buildings peppered between them.

When we meet Dredd he’s suiting up. We meet his Lawgiver Gun, which seems to be matched to his DNA. The whole time, the top half of his face is hidden by his visor, and we only see chin and mouth, “as if they have been carved from rock.”

He chases a car full of Slo-Mo junkies on his motorbike. Slo-Mo is a drug administered via inhaler, and not only does it slow down time for its users, it causes the world to look beautiful, iridescent and bright. When the junkies steamroll some civilians trying to get away from the Judge, they start to die.

Presumably, Dredd has all the authority of police, judge, jury and executioner.

Especially executioner.

While they die, we learn that the Lawgiver is voice-activated and contains many different kinds of ammo. We also learn something about Dredd. He has phenomenal aim, even when he has to place a shot through a civilian, “Remain calm. The bullet missed all major organs, and a paramedic team will be with you shortly.”

Does Dredd get a sidekick in this tale?

Rookie Cassandra Anderson is an orphan who was given a Judge aptitude test (as is standard for orphans) at age nine. Although her score was unsuitable, she was entered into the Academy upon special instruction. When we meet her, we learn that her final Academy score is three percentile points below a pass.

As she stands before the Chief Judge, Dredd wonders why she’s in uniform. When Anderson is able to point out how many people are in the next room observing her, without seeing them mind you, we realize that she’s a psychic, a power she possibly developed as a child because she lived one hundred meters from a radiation boundary wall. While the fall-out proximity made her a mutant, it also killed her parents.

Although she’s failed the Academy, the Chief Judge is giving her one more chance. She’s to spend a day out in the field with Dredd, and he’s to assess whether she makes the grade or not, “Sink or swim. Chuck her in the deep end.”

“It’s all the deep end.”

Dredd informs of her what to expect out there. If she sentences someone incorrectly, she automatically fails. If she doesn’t obey a direct order from him, she automatically fails. If she loses her primary weapon, or if it’s taken from her, she automatically fails.

That’s all the stuff she knows.

What she doesn’t know is that she’s in for the most fucked-up day of her life.

She gets trapped inside of Peach Trees with Dredd?

Yep.

The Judges only respond to six percent of the seventeen thousand serious crimes reported per day, and a slum like Peach Trees, which has a ninety-six percent employment rate, is rarely visited by a Judge.

Because it’s rarely seen a Judge, someone like Madeline Madrigal has risen to power.

A character possibly inspired by real-life bandit queen, Phoolan Devi, Ma-Ma is a former prostitute who supposedly feminized a pimp with her teeth and took over his syndicate. More violent than all of the other crime lords and clans, she runs Peach Tree from her Dolce & Gabbana crack den-esque penthouse on the top floor of the two-hundred story building. She is responsible for the distribution of Slow-Mo in Mega City One.

As a testament to her ultraviolent nature, she has her lieutenants, Caleb, Kay and Sy, murder a trio of dealers who were caught selling a competitor’s product. They pump the dealers full of Slo-Mo, skin them alive (and because the brain moves at one-percent of normal speed while on the narcotic, this must seem to last an eternity) and toss them off the balcony of the atrium that rises through the center of the building as a message.

Of course, Dredd and Anderson arrive to find the bodies, and thanks to a helpful paramedic, they’re told how things work under Ma-Ma’s rule and he tips them off to the Slo-Mo distribution headquarters on Level 39. The Judges shoot up the joint, and we’re treated to our first gun fight which should blow people’s minds in the cinema thanks to the combo of the Slow-Mo point-of-view and the 3D. They manage to capture Kay, who has a tattoo of Judge Death on his chest (undead Judges?) and they get in an elevator to take him out Peach Trees.

Their goal is to interrogate him, learn everything he knows, which will give them enough evidence to return and arrest Ma-Ma. Only problem is, Ma-Ma can’t have this happen, so she has her Clan Techie, a dude who has robotic eye implants like a chameleon lizard, takes control of the building’s computers and he socially hacks Sector Control to run a systems test.

Peach Trees’ system control goes into a nuclear war testing drill and the building is suddenly encased in lead-lined shutters, blast doors that can withstand nuclear attack. Not only does this trap the Judges and the population inside, but it cuts off Dredd’s communication link with Control.

So, Ma-Ma announces to Peach Trees that she wants the Judges dead?

Pretty much. It’s a sequence that sort of took my breath away. I couldn’t help but be glued to the page as Dredd and Anderson are standing in the middle of the atrium, looking up at two-hundred stories of balconies as the clans and warlords begin to organize to collect the bounty on their heads.

You can’t help but wonder how much ammo those Lawgiver guns of theirs have.

As Dredd and Anderson struggle between avoiding detection and their duty as people that embody justice, they have to ultimately decide if they should just escape, or if they should ascend all two-hundred stories to prove Ma-Ma guilty and execute her.

To get the evidence, they have to get Kay to talk. But to get Kay to talk, they have to survive an entire population that is trying to murder them so they can get a quiet moment with him. While things are simple for Dredd, it’s a moral dilemma for Anderson. As a telepath, she is empathetic to some of the people who are caught in the cross-fire, and she really has to decide if all this is worth being a Judge.

How is the action?

Very satisfying.

This thing has fucking micro-genocides in it.

Ma-Ma is willing to kill entire floors full of people to stop the Judges, and she pulls out every weapon and trick and soldier she has to achieve her goal, which may include a quartet of dirty Judges as her ace in the hole.

It’s enthralling and because this is the type of shoot-em-up I love, and because Dredd never takes off his helmet, even when facing his worst fear, I give this an…

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m still impressed that someone is making a comicbook movie that isn’t an origin story. This isn’t about the creation of a hero or antihero, this is about the character being put in a worst case scenario and seeing if he can just make it out alive. It’s a new formula. Take a popular character and put them in a situation that is basically the worst series of obstacles ever. Or take a superhero and put him inside a contained thriller. In a climate where it seems like Hollywood will never tire of making comicbook movies, this script proves that these tales can be told without telling their back story as the movie. Secondly, as a shoot-em-up, Garland has created a pretty cool cinematic device with the drug Slow-Mo. Although it makes the world slow down for its users, it doesn’t give them super-speed. However, there are lots of POV shots, especially in the middle of the action, and it gives those action sequences more of an edge than just a straight shoot-out.

It’s Unconventional Week here at Scriptshadow, and here’s a reminder of what that’s about.

Every script, like a figure skating routine, has a degree of difficulty to it. The closer you stay to basic dramatic structure, the lower the degree of difficulty is. So the most basic dramatic story, the easiest degree of difficulty, is the standard: Character wants something badly and he tries to get it. “Taken” is the ideal example. Liam Neeson wants to save his daughter. Or if you want to go classic, Indiana Jones wants to find the Ark of The Covenant. Rocky wants to fight Apollo Creed. Simple, but still powerful.

Each element you add or variable you change increases the degree of difficulty and requires the requisite amount of skill to pull off. If a character does not have a clear cut goal, such as Dustin Hoffman’s character in The Graduate, that increases the degree of difficulty. If there are three protagonists instead of one, such as in L.A. Confidential, that increases the degree of difficulty. If you’re telling a story in reverse such as Memento or jumping backwards and forwards in time such as in Slumdog Millionaire, these things increase the degree of difficulty.

The movies/scripts I’m reviewing this week all have high degrees of difficulty. I’m going to break down how these stories deviate from the basic formula yet still manage to work. Monday, Roger reviewed Kick-Ass. Tuesday, I reviewed Star Wars. Wednesday was The Shawshank Redemption. Yesterday was Forrest Gump. And today is American Beauty.

Genre: Drama – Coming-of-Age

Premise: Lester Burnham experiences a mid-life crisis after he’s fired from his job, which ends up triggering chaos in his suburban neighborhood.

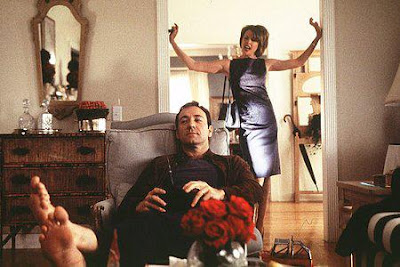

About: Was widely considered one of the best spec screenplays of the last 20 years. But the movie was always going to be a hard sell due to its non-high concept nature. American Beauty went on to become a surprise hit, winning a Best Picture Oscar, as well as 4 other Oscars, including one for Kevin Spacey.

Writer: Alan Ball

Degree of difficulty – 4.5 out of 5

Some of you have suggested that I ditch this mainstream trash and take on movies that are REALLY unconventional. For example, explain why a film like Mulholland Drive works. Well, it’s pretty simple. I *don’t* think Mulholland Drive works. So I’d do a pretty lousy job convincing others of it. I’ve always struggled with Lynch’s appeal. The randomness of his stories always confuses me. So I ask you Lynch-ians, what is the appeal of Lynch’s films? I ask that in all sincerity. I want to know.

Today I’ll be hitching a ride on Kevin Spacey’s train – whatever that means – and reviewing one of the great movies of the last decade – American Beauty. Recently, I watched this movie with a friend who’d never seen it before. I was like, “How could you not have seen American Beauty? It’s awesome.” And she was like, “I don’t know. I just haven’t.” So I forced her to sit down and watch it, and halfway through she turned to me with this frustrated expression and said, “This is just like Desperate Housewives.”

At first I was angry that she wasn’t appreciating the genius of this movie. But I was also trying to figure out if she knew American Beauty came out a decade before Desperate Housewives, and how this would affect our friendship if she didn’t. But after stepping back and thinking about her comment, I realized just how much American Beauty influenced movies and television. It really inspired a lot of copycats, and for that reason, it can never play as original as it did back in 1999. But it’s still awesome, and it still had no business being as good as it was. You want to talk about degree of difficulty, let’s talk about American Beauty.

American Beauty does something I tell new writers never to do: Follow a bunch of characters instead of following just one. It’s okay to follow other characters when they’re around your character, but to jump back and forth between numerous characters and their individual storylines is basically the same as having multiple protagonists. So instead of having to create only one character compelling enough to carry a movie, you have to create six. In addition to that, multiple characters screw up your act breaks and overall structure. You’re essentially having to create multiple three-act stories within a three-act story, and I’m not even going to get in to how hard that is. So yeah, you’re kinda screwed right off the bat.

Also, like a lot of movies this week, American Beauty doesn’t have a very compelling story. In fact, if I described it to you beforehand, you’d probably get bored within 20 seconds. “Well see it’s about this guy. And he like, gets fired. And then he decides to live his life to the fullest. But see, we also watch his family too. And his daughter wants new breasts. And his wife totally hates him. Oh, and the next door neighbors are this military dad and his pot-smoking son…” It just sounds like a slightly exaggerated version of what goes on in everybody’s neighborhood. Why would anyone want to watch that for two hours?

Finally, Lester is an unsympathetic character. He basically says “fuck off” to anyone who doesn’t want to live by his new rules. On top of that, he tries to fuck his high school daughter’s best friend! Let me repeat that. Our 45 year old protagonist is trying to have sex with a 17 year old High School girl. Conrad Hall, the cinematographer on the film, was so concerned about this that he almost didn’t take the job.

Too many characters: check. Weak story: Check. Despicable protagonist: Check. Why the hell did this work?

Ball was smart. He knew that if he followed a bunch of different characters for an extended period of time without a point, we’d get bored. He needed a connective thread – something to bring all these storylines together. He created it in Lester’s death. Ball tells us in the beginning of the movie that in one year, Lester Burnham will be dead. You don’t think much of it at the time, but later you realize that that one sentence turns the movie into a Whodunnit. It’s by no means the dominant focus of the movie, but it gives the movie purpose. I read a lot of these screenplays where writers don’t use that device and they’re almost always bad. In fact, Mark Forster has one of these movies in development called “Disconnect,” (about how we’re all disconnected because of technology). He doesn’t use this device and as a result, the script wanders all over the place.

Next, Ball adds humor. American Beauty deals with some serious ass subject matter. Stalking, death, murder, physical abuse. But the movie is fucking FUNNY. And we’re only able to feel the pain because we’re allowed to laugh. The 7th line of the movie is “Look at me, jerking off in the shower.” Contrast this with another Mendes movie, Revolutionary Road, which had a lot of similarities to American Beauty, but didn’t have a single joke in it. Despite having two of the biggest stars in the world to sell the movie, it bombed. Coincidence? Not thinking so. American Beauty understands that if you ratchet up the melodrama 100% of the time, the audience will turn on you. Make’em laugh and they’ll go as deep as you dare to take them.

Scandalous. A little scandal goes a long way. Old guy with an underage girl? That’s controversial. Controversy intrigues people. It gets people talking. But what Ball managed to do with this storyline was make you understand why our hero did it. This wasn’t about nailing an underage girl. This was about Lester trying to reconnect with his youth. By getting the young girl, it was the physical manifestation of that goal. Also, Ball did a really smart thing by having Mena Suarvi engage in the pursuit. If she would have been some innocent doe-eyed teenager, Lester would’ve looked like a predator. Because she eggs him on, the relationship doesn’t seem nearly as dirty as it could’ve been.

Finally, what I loved most about American Beauty is that I never knew what was coming next. As a writer, it’s your job to surprise the unsurprisable. The audience has seen everything. The readers have read everything. So safe boring choices aren’t going to cut it. Yet, safe boring choices is what I see 99% of the time. American Beauty has its 40 year old protag befriending his 17 year old pot-selling neighbor who’s dating his daughter. It has his wife fucking her real estate rival. It has 5 minute scenes with bags blowing in the wind. It has military closet homosexuals who collect Nazi dinnerware. I can’t remember a movie that consistently surprised me as much as this one. I just never knew where it was going to go. It shows what can happen when you test yourself as a writer and never go with the obvious choice. That’s something we all need to do more of.

Let me finish with this. I’m of the belief that what you have in the script is what you get in the movie. I don’t believe you can do that much to make a script better than it is. Sure you can do a few flashy things here and there, but in the end, it’s about the emotion, and that comes way before a frame of film is ever shot . However, I will concede this belief in one area: the score. A great score can elevate a movie beyond the script. And American Beauty did that. I don’t think without that score that the movie is as good as it is.

Anyway, great movie. Why do you think it worked?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[x] genius

What I learned: The power of a framing device. If your screenplay has little to no plot, look to build a framing device around it. For example, Cameron easily could’ve made Titanic about two people falling in love on a boat, but he knew there wasn’t enough story to that. So he framed that love story inside a present-day search for a jewel. Now the entire movie had purpose, as there was a point to telling this love story. The same thing happens here. We aren’t just jumping in and out of people’s lives randomly. We’re trying to figure out who’s going to kill Lester.

Genre: Dark Thriller

Premise: A dangerous sociopath with a checkered history goes back to his home town island to pay respects to his recently deceased brother, and finds himself stuck in the middle of a major heist.

About: Remember when they did miniatures? Christopher Borrelli used to be the videographer who shot miniatures for movies like Armageddon and Con Air. He more recently moved into writing, tackling assignment work like The Marine 2 and getting his spec Whisper on the 2008 Black List. He busted through with his screenplay, “The Vatican Tapes,” about a leaked video tape revealing a Vatican exorcism gone wrong last year. The script landed on the Black List and was bought by Lionsgate. He followed that up with this script, Wake, which was purchased by Hammer Films earlier this year. Wake is being directed by Kasper Barfoed, the same director who’s helming the script I reviewed the other week, The Numbers Station. Small town!

Writer: Christopher Borrelli

Details: 113 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Wake bases its central character on this premise: 3% of all men are sociopaths, lacking concern for the well-being of others or for the consequences of their actions. 1% of men are born without the ability to feel fear. That means that there is a very small percentage of men who are both fearless and who do not have concern for other human beings. These are probably the most dangerous people in the world.

We’re informed of this at the beginning of the screenplay – actually right before the story begins. So when we meet the linebacker-shouldered Red Forester, we’re pretty sure he falls into this elusive category. I loved Red’s description. It’s one of the better character descriptions I’ve read in awhile: “Something permanently five o’clock shadowed about his soul.” To me, a good description is about giving me the essence of the character – about making me understand as much about that person in as little space as possible. That description captured Red’s essence perfectly.

Red is coming back home to tiny Naskapi Island after a long absence. His brother Sean recently died and he’s trying to make the wake. This is a huge risk for Red because he’s a serial killer – the kind so deadly he’s landed on the FBI’s most wanted list. All Red plans to do is slip in, pay his respects, and slip out. But something tells me it’s not going to be that easy.

Once there, Red runs into his mother, Linda, the owner of the island’s Inn. There ain’t a lot of common ground to go over with your mom when your hobby is killing people, so it’s a decidedly frosty reception. And it doesn’t take long for the other members of the community to pick up on the vibe. Combine it with the fact that Sean never even mentioned he had a brother and soon everyone’s rushing over to that internet thing to find out more about this Red guy.

Sure enough the criminal database tells them that not only is this guy wanted, but there’s a huge reward for him. So they lock Red up and call the FBI. The FBI says they’re sending two agents over right away. But wouldn’t you know it, there’s a big a storm moving in, so it’s going to be awhile before anybody gets here. Well, except for the boat full of 7 really mean looking guys that just showed up.

Led by the menacing in stature but not in name, Phillip Cole, these men mean business. Underneath Red’s mother’s Inn is what’s known as an Icehouse. It’s an area built directly into the rockbed to keep things cold. It’s what they used to use before refrigerators. Well these days, this particular Icehouse works as a vault, and apparently it’s holding something really important, because these men are dead set on getting inside it.

What they don’t know is that standing in their way is a fearless sociopath serial killer. The core group of Islanders, holed up in this Inn, realize that their only chance at survival may require letting loose arguably the most dangerous man in the country. The question is, will he protect them against the bad guys’ onslaught? Or will he put them in more danger than they would’ve been in anyway? The answer may surprise you.

So we really have all the ingredients for a good thriller here. We have an intriguing main character with a compelling character flaw (his inability to feel). We have a contained area so there’s nowhere to run. We have characters who desperately want something (the bad guys). And we have a ticking time bomb (the FBI guys coming). The story couldn’t be set up any better.

But what sets this apart from other scripts is the character of Red. The anti-hero is one of the most fun characters to write because anti-heroes do whatever the hell they want to do. They don’t have that annoying moral compass they have to live by. Having a guy save the kid and buy him an ice cream is boring. Having a guy push the kid out of the way and steal the ice cream is way more entertaining!

The thing you always have to worry about when writing an anti-hero though is getting the audience on his side. If the audience isn’t rooting for your protagonist, whether he’s good, bad, or dead, then you don’t have a movie. Making an anti-hero “likable” isn’t an option because it’s essentially an oxymoron. But that doesn’t mean you can’t get us to root for him, and the best way I’ve found to do this is simple. You make the bad guy worse. However horrible your anti-hero is, just make the bad guy more horrible. Because the more horrible he is, the more we’ll want “our” bad guy to take him out. And if we’re wanting our guy to take him out, that means we’re rooting for him.

Now I wouldn’t call Phillip Cole a particularly memorable bad guy. I would’ve preferred he be more extreme. But he kills anyone who gets in his way, he’s blatantly unafraid of Red, and he’s a dick. So we want to see him go down. And I don’t know what it is, but there’s just something fun about watching the “bad guy” play for your team. It’d be like getting Dennis Rodman or Bill Belicheck. You freaking hate the guys when they’re with someone else, but boy do ya love’em when they’re fighting for you.

The idea for this story may sound familiar to you. I reviewed a similar script called “Gale Force” last month about a group of modern day pirates who use a storm as cover for a heist in a small coastal town. I didn’t think Wake was as good as that script, as I thought the relationships were better explored and the characters deeper. But Wake has the more appealing main character, and I think the lure of playing a fearless sociopath to an actor may be the difference between this project moving forward and that one staying put. In fact, I’m betting the main reason this sold was that someone knew they could get a good actor interested in the lead part.

It’s a great reminder. Write a character that actors will want to play and good things usually happen.

Wake isn’t perfect. It feels like it’s still finding its legs, particularly in utilizing this awesome character of Red, but there’s enough going on to leave you satisfied.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I really like when writers add an extra element of mystery to a story. In this case, I’m referring to what the bad guys are after. A lazier writer might have stuck with the old: “Money on island. We need to steal it,” storyline. Instead, Borrelli sets up this whole “Icehouse” vault and the mystery of what’s inside it. So on top of the bad guy heist, on top of the being defended by a serial killer, on top of all these other cool story elements, we’re also wondering, “What the hell are they after?” It’s just another layer that adds density to the story. — And you can do this with any genre. Always look to add an extra mystery or two because it’s an easy way to give your story additional depth (and it’s fun for the audience!).

Welcome to Wednesday at Scriptshadow. A little busy here in the darkness, so thank God for Michael Stark, who’s come to rescue me with another review. Today he’s taking on a biopic about Margaret Keane. As for me, I’m readying tomorrow’s review, along with my promised mystery post which will give you, dear readers, an opportunity to get your script reviewed on the site. So stay tuned for that. Also, you guys have been writing in about the special $80 April Script Notes deal. Unfortunately all the slots have been filled. But if you’re still interested in getting notes, e-mail me about May. Here’s Michael…

Genre: Biopic

Premise: A drama centered on the awakening of the painter Margaret Keane, her phenomenal success, and the subsequent legal difficulties she had with her husband, who claimed credit for her works. (Logline graciously provided to us by IMDB.)

About: Larry Karaszewski and Scott Alexander (Ed Wood and Man on The Moon scribes) set to direct their own screenplay with Kate Hudson as Margaret and Thomas Hayden Church (who will totally rock) as her hack husband.

Writers: The conjoined twins from a different mother, Larry and Scott.

Details: 125 pages. Undated or specified draft. (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

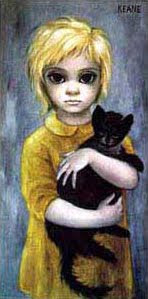

”I think what Keane has done is just terrific. It has to be good. If it were bad, so many people wouldn’t like it.” — Andy Warhol on Keane in 1965

“It’s Keane! It’s Pure Keane. No, no! It’s greater than Keane. It’s Cugat!” — Diane Keaton in Sleeper

Put on your berets and take out your sketchpads, Kiddies, cause Professor Stark is gonna take our class out on a little art history field trip. Carson, please stop doodling on Roger’s back. I don’t care if you’re making chalk outlines of all his dead lice. Must, I turn this bus around, Children?!! You’re the future screenwriters of America, for goodness sake; not friggin artists!

Class. Class? Class!!!

Today, we’re gonna study a script about one of America’s most popular painters, Walter Keane. Yup, the man behind those sad, doe-eyed waifs that infested every freaking, suburban living room in the early sixties. Just take out those old Kodachromes of your parent’s house back then. They had a few kitschy Keanes hanging, didn’t they? Right next to the tiki sculptures, the poker playing dogs and the bullfighter posters. Or, if you were Jewish from up north, next to the obligatory Ben Shahan lithos.

Oy. Stop complaining. Why couldn’t it about some sexy garret-dwelling, turbuculer, alcoholic like Modigliani? Or a volatile, Hamptons-dwelling, womazing. alcoholic like Pollock? Why aren’t we reading a script about some tortured Abstract Expressionism alcoholic who’d rather slice and dice his wrists then sell out like Rothko?

Why? Well, 1. Those have all been done and 2. Cause the auteurs behind this biopic are none other than Larry Karaszewski and Scott Alexander, who would never ever write about the usual Biography Channel suspects.

In fact, they avoid them completely. You’re not going to see them tackling the likes of Amelia Earhart, Nelson Mandela, Charles Darwin or Queen Victoria (four flops that had Newsweek’s Ramin Setoodeh asking last month, “Are Biopics History?”) anytime too soon. They’re more the go-to guys for the wacky, the odball and the offbeat life stories.

They relish in the underbelly of the underdog – The prolifically bad, got-it-in-one-shot filmmaker (Ed Wood), the Pornographer who went to the Supreme Court to battle for our First Amendment rights (The People vs. Larry Flynt), and the baby-faced prankster extraordinaire , Andy Kaufman (Man in the Moon). They even produced (but didn’t write) Autofocus, the flick about the obsessively horn-dogged Hogan’s Heroes, Bob Crane.

The dynamic duo had been attached to other quirky bios including: Liberace, The Village People, Billy Carter and Roland “rainbow man” Stewart, the flamboyantly afroed, super sports fan who was arrested after a shootout with police.

So, what’s the story behind those big, sad, hyperthyroid-meets-them-melting-Dali-watch-sized blue eyes?

Although still immensely popular and influential today, Walter Keane perpetrated perhaps the greatest crime ever known to the art world.

No, he wasn’t a dashing art thief. He wasn’t a master forger. And, it doesn’t have anything about his work being a punchline for critics and the good taste police.

It’s the fact that Walter Keane couldn’t paint. Not a lick. And, the charming huckster for years took credit for his wife, Margaret’s work, banishing her to a sweat shop studio to churn out more and more waif paintings as demand and his fraudulent fame kept growing.

Even the Art History minoring, Professor Stark didn’t know this. And, I though I was a real pop culture vulture when it came to these kind of fun facts.

So under the layers of this kitschy canvas, Larry and Scott have uncovered a gem of a story — The egotistical, huckster Keane and the liberation of his wife, culminating in a classic courtroom drama.

There’s a good reason why those huge eyed tots are always teary!

“Everytime I look into your big brown eyes, I get paralyzed, paralyzed.” – The DBS.

“Movies are life with the boring stuff cut out” – Alfred Hithcock

Seemingly, Dear Readers, you’re gonna accuse me of brown nosing Karaszeski and Alexander (well, I am hiding behind my real name here) or being a very over-generous grader. Cause, you’ll dare say that Big Eye’s first fifteen minutes reads like a flippin’ Lifetime drama.

Well, I agree. But, I believe they did it on purpose. Of course, I’m possibly reading too far into the subtext that might not even be there. But, I think they’re opening in a cliché way to establish how this very passive female got taken in by a smooth talking criminal and why it’s took so many years till she grew a pair and stood up for herself. They’re boldly recreating the whole Feminist Movement of the time. You’ve come a long way, baby!

The script starts off with Margaret leaving her first husband with her eight-year old daughter in tow. It’s 1955 and they land in San Francisco, the Beatnik Epicenter of the cool and the crazy. It’s all Calder mobiles, espresso bars, bongo jazz and reefer — and all totally foreign to Margaret. But, it seems a damn good place to become an artist.

She gets her start sketching cheapskate tourists at Fisherman’s Wharf when she runs into Walter, who very much looks a true artiste in his black beret and turtleneck. He sells his pedestrian Parisian street scenes with flirtations and outrageous carnival barker banter. He takes great interest in shy Margaret’s work and her figure, chiding her for selling herself way too short and much too cheaply. Something, he’ll be a maestro at doing a little later on.

Learning that her ex is out of the picture, they quickly court and set up easels together in the park. It’s a nice scene when the hipster Walter is outed in front of her as having the ultimate squaresville day job — he’s really a commercial realtor. It’s Margaret’s daughter, Jane, that’s the first to notice that Keane’s canvas has been blank the whole time.

When a letter from her ex arrives, calling her an unfit mother, Walter quickly proposes and they’re off to Hawaii for a whirlwind honeymoon. Now, I understand why they chose not to draw out a long custody battle on screen (they’ll have that courtroom scene for the custody of the waif dynasty later), but this news via letter was a big misstep for me. I understand you don’t have to cover the subject’s entire life and that one must frame the story economically and give a reason for their very quick nuptials, but a letter? That just seems so something starring Dame Valerie Bertinelli. Okay, class, what would you have done???

When Walter’s work is snubbed by a snooty gallery owner, his realtor’s training of “Location, Location, Location” finally works for him. He gets the big idea of renting the walls at a hip jazz club, The Hungry I, to exhibit his and his wife’s art.

As both artists in the family now signed their work “Keane”, Margaret’s sad-eyed-ladies-of-the-lowlands are mistakenly attributed to Walter. And, as not to jeopardize a sale, he plays along.

When the dueling egos of Walter and the club owner explode into fisticuffs, a photographer captures it and it’s suddenly front-page news. Suddenly, the club is hot and people are lining up to see the sappy paintings that two grown men were actually fighting over.

As the waif painting start selling like latkes and lava lamps, Walter, trapped in his lie, can’t stop taking credit for their creations. And, then, like any good liar, he starts totally believing it himself, boasting to journalists that “Nobody could paint eyes like El Greco and nobody can paint eyes like Walter Keane.”

Although panned by the critics, the masses fell in love with the waif paintings. The I-don’t-know-a-lot-about-art-but-I-know-what-I-like set had to be suddenly accommodated to. People were stealing posters of their exhibits off the walls. So, Keane, started selling posters and post cards and mass producing cheapo framed posters to keep up with the demand. He brought art ownership to the common man – and made a mint doing it!

Suddenly, everyone wanted a piece of Keane. He opened his own gallery across the street from the very snob who shunned him. He dutifully and brilliantly worked the press and gave portraits freely to luminaries like Kim Novak and Natalie Wood to drum up more and more photo ops. He even sent one of John Jr. and Caroline Kennedy to the White House.

Years before Warhol and Mark Kostabi had their “art helpers”, Keane turned art into commerce. Hell, he had a factory before Warhol even had a soup can. Only his sweat shop consisted of the poor, exhausted, friendless Margaret, locked in a room, painting all day, dazed off turpentine, mass producing as quickly as humanly possible. Slaving like a Cambodian Nike worker while Walter basked in the ill-gotten fruits of his self promotion.

No one was allowed to know their secret. Not even her own daughter!

The passive and voiceless Margaret meanwhile spirals deeper and deeper into depression; her waifs becoming much older and sadder. They’ve all become self-portraits. And, somehow, Walter has to explain to the world what has inspired him to paint all those cute kitten and crying, huge-eyed women. Jeepers creepers, everyone wanted to know how he got those peepers.

Usually Scriptshadow’s secret bylaws strictly forbid us from spoiling the third act, but this is a bio pic. The story has already played out. Let’s just say that like in Larry Flynt, Margaret does get her day in court, finally proving to the world who the real artist in the family was.

As life seems to provide more suspending of disbelief moments than movie usually do, Margaret’s sudden transformation from exploited door mat to hear-me-roar truth seeker all came about after a pair of Jehovah’s Witnesses knocked on her door. Guess they were pretty damn good witnesses. It’s a little unbelievable and pat, but, hey, that’s exactly what happened in real life.

Vindicated, justified and finally happy, Margaret Keane’s saucer-eyed paintings still shed a tear or two. But, now, they’re tears of joy! As this film has already been cast, do keep Thomas Haden Church in mind while reading Walter. Watching him squirm at the end as his empire implodes is just gonna be a pure delight.

Now, for the grading. I wanna give these guys an A + for effort. Their ability to find truly unique source material is incredible. I give them an impressive for the research alone.

But, I have to dock a few points on the execution. Now, as I always preface every script review, I have no idea what draft I’ve just read. Could have been the first, could have been the shooting script. Who the hell knows. I’m hopeful that some of the kinks have already been worked out. But, these guys are directing Big Eyes themselves and I’ve seen their directorial debut, Screwed. Funny flick but not quite up to par with Tim Burton or Milos Forman, who I’m certain were quite real hands on during the rewrites.

Certainly, the ultra passive Margaret will get some life breathed into her by Kate Hudson’s people. I would like to see her transformation and realization of what a twat her husband is a little bit sooner. Also, the court case — The Mister-Smith-Goes-To-Washington-Mailbag moment — just flies by too quickly. This is the weighty scene we’ve been waiting for. We would like to see her really speak up for herself here.

Although Walter has some comic foils like the snooty gallery owner to parry with, the boys missed a wonderful opportunity with John Canaday, the snarky art critic of the New York Times. It was one of his scathing reviews that stopped the World’s Fair from displaying Walter’s masterpiece (well, uh, her masterpiece that he appropriated). The Critic’s mission to wipe the kitschy Keanes from the face of the serious art world comes way too late. He should have been brought earlier on as a common enemy that would bond the couple. By the time he comes on the scene, they’re already divorced. He also could have also been the one to suspect that Walter was really zooming the scene, a hack whose only talent was self-promotion.

Thus, I give Big Eyes a double worth the read. I wanted to be impressed, but… Oh, well, maybe next time when they tackle the Family Circus’s John Hughes lookalike, Bill Keane.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I had helped a writer buddy once adapt his published bio into screenplay form. The guy’s frantic life made for some wonderful scenes but it took a lot of tinkering to get his narrative to drive straight. You have less than two hours to tell someone’s life story. What exactly do you focus on? What are the defining moments? What are his or her character arcs? How do you keep your story from sprawling out of control like an Atlanta suburb? Big Eyes focuses on the ten year span after Margaret married Keane and became a virtual prisoner to his ego, culminating in their divorce and court case. We didn’t need to see too much of her life pre San Francisco nor did we need to see her in a flash forward today, remarried and still painting. What you leave out for the story is almost as important as the scenes you keep in. It also helps. in the cases of the Blind Side and the Pursuit of Happiness, when your main characters aren’t famous people whose every movement have been recorded in the history books. Excepting of course, if your history books have been published in Texas.

So, Kids keep reading. You just might find the next great Biopic in the Parade section of your local paper!