Search Results for: F word

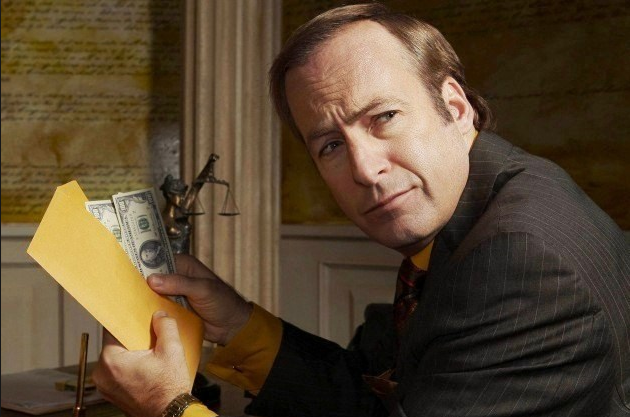

So I recently finished watching the fifth episode of Better Call Saul (this does not include last night’s episode), and I have to say, the Breaking Bad spin-off series has surprised me. Not just because it’s pulled me in, but because the big picture writing on the show is nowhere to be found. This is a show that’s hooked its viewers on an episode-by-episode basis, an unheard of strategy in a serialized TV program. And if I’m being honest, I have no idea how Gilligan plans to keep it up. I mean, Breaking Bad was masterful in its big picture writing. And that got me thinking about the differences between the shows. Why is it that Breaking Bad is so much better than Saul? I’m glad you asked. Because I’ve broken it down into six big reasons. Let’s take a look…

OVERALL STORYLINE

In order for any story to work, it must have an engine. The engine is the thing that pushes the story along underneath the hood. In a feature, that engine needs to rev high and fast (stop the alien invasion, execute the heist). In TV shows, since the story needs to last a lot longer, that engine will rev slower and longer (find a way off the island, find a surviving community in a zombie apocalypse). Breaking Bad had a great overall storyline. Walter White needed to make a ton of money before he died of cancer so that his family would be supported after he died. Every episode in that first season ran on that engine. What’s the overall story engine in Better Call Saul so far? There isn’t one. I guess it’s sort of “Let’s see if Saul can start a business” but that’s hardly in the same engine category as dying of cancer – save my family.

MAIN CHARACTERS

One of the keys to making a TV show work is creating a sympathetic lead. That’s no different from how they do it in the movies. Walt was one of the most sympathetic characters we’ve ever seen. The poor guy had terminal cancer, a son with special needs, a new baby on the way, was the best at what he did, and was an underdog in every sense of the word. He’s a brilliantly conceived character who’s impossible not to root for. Saul is sort of an annoying fast-talker. Vince tries to create sympathy by pushing Saul out of his big corporate law gig, creating another “underdog” scenario in a sense. But it just isn’t the same. We do root for the guy, but it’s more out of curiosity than need. We NEEDED Walt to figure out how to save his family. Also, doing something for one’s self is never going to be as sympathetic to an audience as doing something for others.

DRAMATIC IRONY

Breaking Bad’s single biggest trick was the dramatic irony that was woven into the core storyline. Walt has a secret. He’s a drug dealer. It’s a secret he’s keeping from his family, his work, his friends. And that alone implores us to keep checking in week after week. We want to know, “Is this the week someone’s going to catch on?” “Is this the week he finally gets caught?” Gilligan knows he doesn’t have that with Saul, so he uses other tricks to pique our curiosity, such as Saul’s weirdo brother who believes he’s allergic to electrical impulses and has to live in a house devoid of electricity. It definitely pulls us in at first, but it is, ultimately, a gimmick. And gimmicks can only last so long.

TICKING TIME BOMB

Another factor that worked well for Breaking Bad was that it had a ticking time bomb woven into the setup. Walt was dying. He didn’t have long to live (at least initially). So he had to move fast. There’s no big picture urgency at all in Better Call Saul. This is on full display when you notice there are a lot more “sitting down and talking” scenes. When there’s no urgency, there’s a natural tendency to write more talky scenes because what else are you going to do? Your characters clearly have the time. In an early episode of Saul, the one where the family stole the money, the urgency is there. But in some of these other episodes, it’s not. Incidentally, this is what’s killing The Walking Dead this season. Unlike past seasons (going after the Governor, trying to get to Terminus), there’s little-to-no engine driving the season, and because of that, no urgency. It isn’t a coincidence that all the characters are now sitting down and having long talks with each other that bore us to pieces.

CONFLICT

Another genius move by Gilligan in Breaking Bad was creating this “buddy cop” scenario (with Jesse Pinkman). Two completely opposite personalities who are forced to work together to achieve the same goal. You know instant oatmeal? By creating a “partners who hate each other” scenario, you get instant conflict. You never have to come up with some artificially constructed scene to create contact. It’s built into the key character relationship so it’s always there for you. One of the reasons Better Call Saul feels slower and quieter than Breaking Bad is that it lacks this component. Saul’s only real buddy is Mike, and Mike isn’t exactly a talker.

PROGRESSION

One of our favorite reasons for tuning into Breaking Bad every week was the progression. We loved watching Walt and Jesse move up the ladder, particularly because it was a world they had no business succeeding in. There was something delightful about a chemistry teacher becoming the best drug dealer in the city. This is the one area that Gilligan is trying to match in Better Call Saul. He’s hoping we’ll get involved in Saul moving up the ladder and becoming a successful lawyer. The big difference here is that a) Walter’s rise was ironic – a nerdy chemistry teacher becoming a badass drug kingpin. Saul’s rise is pretty straightforward. A low-rent lawyer trying to make a name for himself. And b) We already know where Saul ends up – in some rinky-dink operation in a strip mall. Whereas with Walter, the possibilities for success were endless, we can never experience that with Saul (which is why I hate prequels – but that’s a story for another article). I suppose Saul could rise before he falls, but we still always know where he ends up.

Now I point all this out not because I want Saul to fail. I actually desperately want the show to succeed. There isn’t a lot of quality television out there and I like this universe Gilligan has created. Still, I’m fascinated, from a writing standpoint, with how Gilligan plans to make this work. The first series of episodes have been solid on an episode-by-episode basis. But like I said, to get an audience invested in the long term, you need to give them a peek under the hood. You need to show them the engine. And I don’t see that yet – or at least, I don’t see an engine strong enough to keep this car running all the way to the finish line. TV shows, way more than movies, need to be built atop solid foundations. If the plan for the show isn’t known, writers eventually must resort to tricks and gimmicks (big twists, main character hookups) to cover up the fact that they have no idea what to do next. This is why certain shows that were good at first (Prison Break, Heroes) went off the rails quickly.

For those who’ve seen the show, do you enjoy it? Why do you watch it? Do you agree that there seems to be a lack of a master plan? Does that bother you? Chime in below. I’m curious as hell to know what you think!

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Western

Premise (from writer): A grizzled alcoholic travels by hook or crook across the Old West to bury his brother but is hunted by those he’s wronged all the way.

Why You Should Read (from writer): Last time I was here, I was dominated by the Benny Pickles script “Of Glass and Golden Clockwork” and deservedly so. Despite not winning the coveted Friday slot, I was still given a TON of awesome advice on how to better my script (Monty), and was subsequently a Top 10% in the Nicholl Fellowship. Not huge accolades, but for my first screenplay? It felt good! — This is now my third script and I feel like I’ve gotten better since I submitted last. But this is a Western, damn it, and nobody wants them anymore. It truly needs to be the absolute best it can be to get any sort of traction. I really hope that the ScriptShadow community can help me again whether I move beyond AOW or not.

Writer: Benjamin Hickey

Details: 97 pages

Can we bring Paul Newman back for this one?

Can we bring Paul Newman back for this one?

Are you a writer who loves Westerns?

Are you frustrated by Hollywood’s disdain for the genre?

I’m going to help you out. Find a fresh angle. Mix a Western up with another genre. Something it’s never been paired with. Take an idea that would normally have nothing to do with Westerns and infuse it into a Western. This is the only way you’re going to make a Western spec stand out.

That’s not to say you can’t write a Western the traditional way. True Grit did well a few years ago. Jane Got a Gun is coming out later this year. But the best way to get Hollywood’s attention is to explore a genre in a way that it hasn’t been explored before. Westworld is a perfect example. Once as a film and now as a show coming to HBO. Surprise us with your Western take.

Where does Oakwood fall on the Surprise Scale? Well, I’ll give the script this. It’s different. Not different in the way I was just explaining. More like different in the way going backwards on a roller coaster is different. Confused? I’ll do my best to clarify.

It’s the old West. An alcoholic drifter named Hearse, so named because he wheels a casket around wherever he goes, is in the market for a horse so he can travel to another town and bury whoever it is who’s in this coffin. But when a local rancher won’t give him a good deal on a horse, he shoots the rancher and takes the stallion.

What Hearse doesn’t know is that the rancher’s wife, Emma, who’s fucking the stable boy when all of this goes down, is one vengeful little lady. She grabs her stable boy, the slow-witted Wally, and tracks Hearse to the next town.

Now Emma never actually saw Hearse, so her plan is to wait by her horse, which has been parked outside the bar, and shoot whoever comes to claim it. Problem is, Hearse figures this out and sends the town drunk to the horse instead. Emma and Wally mistakenly shoot that man, think they’ve avenged her husband’s killer, and go home.

I hope you’re following so far cause this is where things get crazy. It turns out that the man Emma erroneously killed was a member of the notorious Winchester 7. This nasty gang is led by Jackson, a deputy who kills first and asks questions…well, never. And Jackson, like Emma, isn’t the kind of person who just lets murderers go. Hence, he and the gang go off to kill Emma.

The thing is, Emma’s able to kill the first Winchester who gets to her. This helps her realize that she originally killed the wrong man. So she and Wally go BACK to the town AGAIN to kill Hearse, who she now knows to be the true murderer. In the meantime, Hearse kills a Winchester 7 as well (for a badass gang, their guys sure do die easy), meaning he’s now a target too.

This means that Emma and Hearse will have to team up to defeat the rest of the 7, with an agreement that once they’re all taken care of, it’s a showdown between the two of them, where only one will come out alive.

Phew!

You guys get all that?

Okay, a couple of initial thoughts here. I love that Oakwood is a lean 97 pages. I’m a big advocate of WASO (Writers Against Script Obesity) and I’ve noticed that a lot of Western writers over-share when it comes to words. Oakwood’s lean writing style helps move the story along quickly.

Hickey was also very aggressive with his plotting. It seemed like the script changed direction dozens of times, leading to an impossible-to-predict storyline. I have to give it to Hickey. I rarely knew what was going to happen next.

But this is also where I began to take exception to Oakwood. Something about its unpredictability made it hard to engage in.

Before we even get to that, though, I’d ask Hickey, who’s the hero here? Is it Hearse or is it Emma? Hearse is introduced first but he’s such an unlikable person (he gets shitfaced drunk all the time – steals a man’s horse then kills him) that you’re convinced the hero has to be someone else.

The thing is, Emma’s not that likable either. She’s introduced banging the stable boy while her husband is outside getting murdered. This leads to a baffling development where Emma recruits the man she just cheated on her murdered husband with to avenge her husband’s death.

How am I supposed to root for either of these people?

We spend the rest of the screenplay jumping back and forth between Hearse and Emma’s point of view, all the while trying to figure out whose story it is.

And look, I’m not saying you HAVE to have a single protagonist in every script. But if you do have two, your story will be twice as difficult to tell. And furthermore, if you make both of those protagonists unlikable, you’ve made your story four times as difficult to tell. This is the predicament Oakwood finds itself in.

What’s funny about this script, though, is that it never completely falls off the rails. Every time you’re ready to dismiss it, it reels you back in. It’s a little like Jason from Friday the 13th in that sense. You can’t kill him!

Take Jackson, for instance, – the most evil Deputy in Western history. He enters the script around the midpoint and he’s so nasty (he shoots his boss dead in cold blood) that we won’t be satisfied until we see him go down.

This rejuvenates our deadbeat protagonists, whose unlikableness we’re ready to forgive for as long as it takes to turn Jackson into tumbleweed stew.

And then there’s the dialogue, which is pretty darn good. Emma’s admission to Wally after realizing she shot the wrong man results in this great line: “I think we need to be a bit more careful who we put bullets in.” Or when a fellow Winchester 7 seems frustrated that Deputy Jackson would consider this “little girl” (Emma) dangerous, his response is perfect: “I know that little girl is a human being. What I know about human beings is you put them in certain situations and they’re all dangerous.”

There’s no question that there’s something here and that Hickey is an interesting writer. But three things are holding this script back.

1) It’s not clear who the protagonist is.

2) Neither of our dual protagonists is likable.

3) The plot jumps all over the place.

You can get away with one of these in a screenplay. If you’re a skilled writer, you may even be able to get away with two. But I don’t think you can get away with all three. And that’s where Oakwood’s problem lies.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Hickey makes an interesting choice here to reveal his protagonists’ sympathetic qualities late in the script. This is a risky move because readers tend to form definitive opinions on characters early. So if you introduce a character being an asshole, we’re going to dislike him. By the time you reveal that there are legitimate sympathetic reasons for him being an asshole on page 75, it may be too late to change our minds. To combat this, you have to give us at least SOME positive qualities in the meantime. Give us SOME reason to root for this person as the plot unfolds.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: After America’s favorite astronaut nearly loses his life in an accident, the government decides to rebuild him into a bionic man. The problem? Money for the project is tight.

About: Jonathan M. Goldstein and John Francis Daley are one of the hottest comedy writing teams in Hollywood. They wrote Horrible Bosses, Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2, and recently won the plum assignment of rewriting National Lampoon’s Vacation. This is the script that got them noticed. It landed on the 2007 Black List, and although it never got made, it started their careers.

Writers: Jonathan Goldstein and John Dale

Details: 100 pages (undated)

Aspiring screenwriters all live with the same dream of writing a screenplay, getting it into the right hands, said hands loving it, and a studio sending them a check for six figures. While those moments always get the most press because of how rare they are, the more well-known path is for a writer to write something that shows promise, then use that to build credit in the industry, which they’ll then cash in on later with another spec.

Cause what happens when you’re a “nobody” writer and you write something good is that everyone in town is afraid to buy it. They don’t want to be the “dummy” who just spent a boatload of money on an unknown. Tinseltown people are horrified of being the laughing stock. But what that first script does give the writer is “street cred” so that, now, when they write another script, people aren’t as afraid to pull the trigger because the writer is no longer “unknown.”

That’s the kind of script we’re dealing with today. It proves to the industry that you’re close. How do you write one of these scripts? One of two ways. Come up with a great idea and execute it adequately. Or come up with a so-so idea and execute it exceptionally. The former is the waaaaaay easier route to go, and that’s squarely where $40,000 Man lies. This is a really clever concept. It takes a known property (the 6 million dollar man) and flips it on its head with a funny question (What if they had to make the bionic man on a budget?). Let’s see how the script fares.

It’s 1973. Buzz Taggart is America’s favorite astronaut – a star amongst the stars. His only crime is that he’s a few craters short of a full moon. And one day when some annoying teenagers challenge him to a drag race, his idiocy gets the best of him. He crashes badly and the government tells him that the only way they can save him is if they put him back together with bionic parts.

Buzz is happy to be alive, don’t get him wrong, but he’s less than thrilled when he finds out this “program” he agreed to is on a super tight budget – as in only 40,000 dollars. This has left his new supposedly awesome bionic powers somewhat… lacking. For example, his bionic arm just randomly punches people. His bionic legs (which only run 1 mile an hour faster than the average human) can’t stop once they start going. Oh, and his bionic nose can only smell one thing – shit.

Buzz is placed on his first mission right away, but as you’d expect, it goes horribly. So the government SCRAPS the project due to money, leaving poor Buzz living life as a rapidly deteriorating heap of scrap-metal. To make matters worse, he finds out that the government was lying to him! Buzz was a guinea pig. A pre-cursor to a newer better bionic man worth SIX MILLION DOLLARS!

One year later, depressed and washed up, Buzz gets a call. The six-million dollar man is missing! And they need Buzz to save him. Buzz demands that they upgrade him first, so they tack on 10,000 dollars worth of new parts which… don’t really do anything. Buzz then heads to an island run by terrorists to save his replacement and become a hero once more. In order to do so he’ll have to overcome a body that may be the worst government project in the history of the United States.

The $40,000 Man is pretty much the perfect career-starting script. That’s because while it may not be great, it shows a lot of potential. The first way it does this is by nailing a good concept. This is a seriously over-ignored aspect of screenwriting. No matter how many times I talk about the importance of it on the site, 80-90% of the scripts submitted to me are dead in the water before I read a word.

Either the idea’s devoid of conflict, isn’t exciting enough, lacks irony, or isn’t big enough. A lot of writers delude themselves into thinking that they can turn mundane topics into gold with their execution. And sometimes you can (staying within the comedy genre, “The Heat” comes to mind). But go look at the top 50 grossing movies every year over the last 10 years and you’ll rarely find small ideas. Almost all of them feel “larger-than-life.” And that’s a good way to look at concept. Think big.

In addition to a big idea, irony is a great way to set your concept apart from others. Since $40,000 Man is based on an ironic premise, it immediately shows the industry that the writers know what they’re doing.

Once you come up with a good concept, you must execute it adequately. And that mainly means structuring your story well. It doesn’t have to be perfect. Again, you’re just trying to show that you have potential. But you must show that you can sustain a story for 110 pages. One of the easiest ways to spot a new writer is a script that loses momentum around the page 40 mark. This is where most beginners fall because they don’t yet know how to structure their screenplay so that the story lasts.

For example, in $40,000 Man, Buzz gets fired and abandoned at the mid-point of the story. This was an unexpected twist that gave the story new life. Soon after, he’s re-recruited, ironically, to save the 6 Million Dollar Man, and the story builds from there until the climax. The writer who’s not yet ready writes a few “fun” scenes once Buzz gets his bionic powers and then isn’t sure where to go next. To him, the “fun” scenes were his whole idea so he hasn’t really considered what to do once they’re over (hint: it starts with adding a goal!)

Just a warning. Readers only give you leniency with your execution IF YOU HAVE A GOOD CONCEPT. If you already botched the concept, so-so execution will be the nail in the coffin. For writers who argue that their script was attacked for lazy structure/execution while [recent spec sale] had lazy structure too and still sold – chances are it’s because their concept was a lot flashier than yours and therefore received a longer leash from the reader.

Remember, any idiot in Hollywood can spot a great script because there are only 2-3 of them a year. With everything else, agents and producers have to spot potential. Potential in a script that’s not yet there or in a writer who’s not yet there. If you can give them a great concept and an adequate execution, you’ll have a shot at getting noticed. These scripts are “table-setters.” They’re not amazing, but they set the table for you to start selling screenplays.

By the way, this one shouldn’t be hard to find. It’s a 2007 script that has been traded forever. So ask around and you’ll likely receive.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Set up late-arriving characters earlier if you can. A common beginner mistake is to throw new characters into the story late. Because the characters have little time to make an impression, the reader never truly connects with them, so they, along with whatever storylines come with them, fall flat. This happened with the Six-Million Dollar Man (Steve), who comes into the story around page 70. I barely knew this guy so I didn’t care if Buzz saved him or not. You should try to set up every important character as early as the story will allow you to. So here, why not make Steve someone Buzz worked with at NASA? Maybe Steve worked in a lowly position and Buzz was a dick to him. I don’t know. But just by creating a history between these two, the Six Million Dollar Man becomes way more relevant as he takes center stage in the 3rd act.

Today I’d like to discuss an often overlooked aspect of screenwriting – the angle. The “angle” one tells his/her story from is often what separates the pros from the amateurs. You see, coming up with an idea is only half the battle. Once you’ve done that, you need to figure out the way you’re going to tell that idea. This is the “angle.” And it can turn a boring idea into something extraordinary.

This hit me like a bolt of lightning recently when I caught the new Showtime show, “The Affair.” Now let me ask you a question. Take a look at the poster above. Between that and the title, what are you imagining this show to be like? If you’re anything like me, you probably imagined a straight-forward soap-opera like story about a man who’s bored with marriage who engages in an affair.

And if you’re anything like me, you probably said, “That sounds boring as hell.” It’s not to say that it can’t be good. Maybe they execute the shit out of that idea and it turns out solid. But here’s how I see it. If the premise of your show/movie is something that is often the subplot of other shows/movies, it’s probably not a very strong idea.

And then I watched the show.

And I was blown away.

The genius of this show is the ANGLE. Here’s how it works. We meet a family man, Noah, with four kids and a wife he met in college. The family heads up to their beach summer home, and it’s there where Noah runs into local waitress, Alison. Alison is also married, but, as we’ll find out later, having problems in her marriage due to the loss of their child.

So far, so boring, right?

Except the first half of the show is from Noah’s point of view and the second half is from Alison’s point of view. The show had me hooked after a particular scene late in the pilot. We’d already seen this scene once from Noah’s point of view. In it, Noah comforts Alison after she’s shaken up from his daughter choking. In that scene, Noah is wearing slouchy shorts, a lazy wrinkled shirt, and he looks every bit the role of the overworked parent. In other words, his view of himself. He’s also very bumbling when he speaks to Alison, a woman he’s obviously a little attracted to. She looks sleek and perfectly put together in the scene, and she always seems to say the perfect thing.

Later, in Alison’s version of events, Noah is now wearing a buttoned up stylish shirt. He looks more tanned, more handsome. She, on the other hand, is the bumbling mess trying to get the right sentence out. Her look is pale, her teeth just a tinge less white, her hair a mess. In other words, how she sees herself. The show, then, is a brilliant study not just of two different points of view of the same events, but in how we see ourselves in this world compared to how others see us.

Yet a third element of the show is a running voice over from both characters recounting the affair to a detective. It appears that someone, at some point, was killed, and the police are looking into it. The details of this affair are helping them piece together what may have happened. This, of course, is why we’re getting both sides of the affair – because each person is telling their version.

This, my friends, is what you refer to as “angle.” An affair is boring. It has been done a billion times before. Sarah Treem found an angle, however, that made it fresh, that made it different.

The power of “angles” first struck me in my interview with Ben Ripley about his amazing screenplay, Source Code. Ben admitted to struggling with the idea, at first, of a train wreck involving time travel. He wrote a number of drafts that started after the train had crashed, with a mysterious government group coming in to use a new technology that allowed them to go back in time to figure out what happened. It was a very straight-forward version of the idea, he conceded.

It wasn’t until fooling around with the idea for awhile that he realized he needed to place the story inside the point of view of one of the passengers on the train. That was the “angle” that turned another boring sci-fi idea into one of the best screenplays of the decade.

What are some other examples of “angle” elevating a screenplay? Well, let’s say eight years ago I pitched you an idea about a group of guys who have a crazy bachelor party in Las Vegas. “It’s going to be awesome!” I claimed. “Think of all the zany wacky adventures that could happen to a group of guys partying in Vegas.” Yet the look on your face conveys one of confusion. “That sounds like the most boring straight-forward idea ever,” your eyes say.

What if I then said, “Well wait, let’s change the angle. What if instead of chronicling the night itself. What if they got so wasted they don’t remember anything from the night before. And in the process, they lost the groom! So the movie takes place the next day, as they try and piece together where they were so they can find the groom and make it back to the wedding in time.” Boom, your face lights up. “Now THAT’S a movie!” This is the same general concept, just told from a different angle.

There was no one more flummoxed by the overspending they were doing on this JJ Abrams pilot called, “Lost,” than Disney head Michael Eisner. “I don’t get it,” he would tell anyone who listened. “They crash on the island. Then what???” Eisner was quick to note that the pilot would be exciting. But wouldn’t the viewers get bored when, by episode 10, they were coming up with the 8th different way to try and find a way home?

Eisner clearly hadn’t read the series bible, which stated the unique angle the show would be explored by. Instead of some traditional, “Try to get off the island” show, each episode would be dedicated to going back in time to explore one of the passenger’s lives before the crash. These backstory reveals would then be woven into the present day island story in a way that brought the two worlds together. This was the “angle” by which Lost became one of the greatest television shows in history.

Now I don’t want to scare you. You shouldn’t try to find some amazing never-before-seen angle for your movie/show every time out. Some stories are best told in a simple straightforward manner. E.T. is a wonderful heartwarming movie. I’m not sure it would’ve benefitted by some wild angle like being told backwards or from the point of view of the alien.

Generally speaking, the more common the subject matter, the more the need for an angle. Without the jumping-around-in-the-relationship aspect of 500 Days of Summer, it’s just a straight-forward story about a couple who wasn’t right for each other.

Also keep in mind that you’re not always going to find the angle right off the bat. Sometimes you have to get into the story and write a few drafts before you realize the story could be better told another way. This is exactly what happened with Source Code. Sadly, a lot of writers will get a few drafts into a script and, even though they know it’s not working, say to themselves, “Well, I’ve already committed to this angle. I might as well play it out.” No. No no no no no no no. Why put more time into something that’s not working? Feel out the angles. Look for one that’s more exciting.

And now for some fun. Let’s see if you learned anything from today’s article. Below, I’m going to give you an idea. In the comments, I want you to pitch your ANGLE for that idea. Whoever comes up with the best angle (in my opinion), I’ll give them an AUTOMATIC BID into the SCRIPTSHADOW 250 CONTEST. Make sure to upvote the angles you like. I’m curious to see the popular consensus winner as well. Good luck!

A family boat trip goes awry when they accidently drift into the Bermuda Triangle.

Feel free to pitch either a movie or a TV show. I’ll announce the winner tomorrow on Amateur Friday. Good luck!

Genre: Crime/Drama

Premise: A female FBI agent is dragged into an undercover operation to take down one of the biggest drug tunnels in Mexico.

About: Actor/writer Taylor Sheridan has just beefed up his resume. He first made waves with the well-received Black List script, “Comancheria,” but seems to have really come-of-age with “Sicario,” which has Prisoners director Denis Villeneuve attached and Emily Blunt in line to star.

Writer: Taylor Sheridan

Details: 105 pages (undated)

Alert alert! Do you have a memorable title for your screenplay?

One of the funny things that happens every once in awhile at Scriptshadow is I’ll be scrolling through my database of scripts to see what I want to review next. I see the title of a script along with the writers, then do a Google search of both to learn more about the project. Sometimes, the first result will be: “REVIEW FROM SCRIPTSHADOW.”

WHAT??? I already reviewed this? I’ll go to the review, read it, and, sure enough, find out I did read and review the script. This may sound like a humorous scenario, but it’s a terrible one if you’re the screenwriter. If someone can’t remember your script from the title, it probably means you have a forgettable title.

The script in question was one I actually reviewed quite recently, called “On Your Door Step.” It was a pretty good script. But obviously, that title doesn’t lend itself to being remembered past a few weeks. In order to be memorable, you should be more specific. Take the recent surprise hit, “John Wick.” That’s a memorable title mainly because it’s highlighting a specific name. Do you know what the original title for that script was? “Scorn.”

Scorn???

Talk about a boring forgettable title. We’ve been hardwired by the studios to give our scripts the most dumbed down titles possible, not realizing that the reason they’re doing this is that the more general the title is, the more demographics it can potentially appeal to. As a writer, you have a very different purpose with your title. You need to stand out. So try a few specific titles on for size with your latest screenplay and see how they fit. It may make a big difference when you enter your script into The Scriptshadow 250 Contest.

Today’s much more memorably titled screenplay, Sicario, focuses on FBI agent, Kate Macy. Kate’s been cleaning up the streets of Phoenix with her partner, Reggie, who’s been trying to get out of the friend zone with her for years. On this particular day, the two stumble into a house for a routine kidnapping only to find dozens of dead Mexican bodies hidden in the walls.

Soon after, Kate is recruited by the mysterious Matt Graves, a guy who looks more like the drunk divorced dad at the end of the Tiki Bar than the Department of Justice agent he is. Matt tells Kate he needs her for the big time, and flies her down to the Mexican border, where he shows her just how terrifying the war has gotten.

Every single Mexican cop is controlled by the cartels, so the days of waltzing into the country and throwing their American weight around are done. These days, they have to be smarter about how they attack. Immediately, Kate senses something is off. Why the hell would they want her for all of this? She specializes in kidnappings, not inter-border war games. But Matt remains tight-lipped.

Kate soon realizes how dangerous her new job is. When she meets a good-looking guy at a bar, it turns out he’s been hired by the cartel she’s watching to assassinate her. Kate’s new status has put her on some “list,” which means going back to her old job is no longer an option. She’s in it whether she wants to be or not.

Eventually, Kate learns that this entire operation is about locating and taking down the cartel’s biggest smuggling tunnel. They do that, Matt promises, and all the drugs back in Phoenix will disappear. For once, he assures her, she has an opportunity to really do something impactful. This would be all well and good if Matt was telling her the whole truth. But it turns out he’s using Kate. For what? You’ll have to read the script to find out.

The wide-release crime-drama has gone the way of the dodo bird. The older folks who used to go to the theater to watch these films would rather stay at home and see what’s on Netflix these days. So how is Sicario getting made? I’ll tell you how. Because this is a sweet-ass script – like a bowl of Captain Crunch doused in chocolate milk. And I wasn’t expecting that at all. Most of the crime-dramas I read are “already seen it all before” boring. I’ll tell you why this one wasn’t.

When I read a script – especially when I read the first ten pages – I have this subconscious filter going on, where I’m looking for anything that’s UNIQUE. It could be a line of dialogue. It could be a line of description. It could be a scene. It could be a character. Whatever. If I read 2 or 3 things that I haven’t seen before before the 10 page mark, that’s usually a good sign.

There were three such moments in the first 10 of Sicario. First, we get this line about a character’s eyes. Now I’ve read every eyes description you can possibly think of. And they’re all usually the same. This is how Sheridan describes one of his characters: “He looks young for 35, but his eyes – seems like they lived for decades before him.” I like that. I haven’t seen that before.

This is followed by the house bust scene where our agents quickly realize that over 3 dozen men have been buried in the house’s walls. I haven’t seen that in a crime-drama before. Later in that same scene, a door is rigged with explosives, killing two men in front of Kate. Afterwards, when she goes home, we get a scene of her showering, carefully pulling off the bits of flesh and bone stuck to her from the explosion. Again, have not seen a scene like that before.

So I was pretty much in immediately.

Sheridan does a number of other things well, too. First, Matt doesn’t tell Kate exactly why she’s been recruited for this mission. This leaves her, and us, in the dark, turning the pages in hopes of finding out the answer. Things would’ve probably been boring if Matt told us exactly what we needed to know right away. One of your jobs as a writer is to hold back information every once in awhile to keep things suspenseful. Never forget that.

Sheridan also does a nice job with Kate’s partner, Reggie. Matt doesn’t want Reggie here. He only comes along because Kate won’t cooperate without him. There’s then a ton of conflict whenever the three are around each other because Matt literally treats Reggie like a 3rd class citizen. He is an ant as far as Matt is concerned. This enrages Reggie, keeping lots of tension in the scenes whenever the three must interact.

Also, Sheridan doesn’t make Kate and Reggie a couple. Amateur Screenwriting Mistakes for $100, Alex? He makes them partners only, with Reggie secretly in love with Kate. Again, this creates more conflict, since we can feel Reggie’s love for Kate throughout the screenplay. As a screenwriter, one of your biggest goals is looking for areas to create conflict between your characters. Sheridan does this really well.

And he’s also a really great scene-writer. The best scenes usually come down to the writer’s use of suspense. Even if nothing I’ve mentioned so far has interested you, you need to read this script (I think it’s on scribd.com? – do a Google search) for the Border Shootout scene. This is a fucking awesome scene. In it, our team is trying to get back into the U.S. at the border, but they are 50 cars back in line. They start to realize that various cars in line are Cartel members who are about to turn them into swiss cheese. And they’re sitting ducks. What happens next is freaking awesome. That scene’s going to rock.

The only reason this script doesn’t get an “Impressive” is because Kate’s not a deep enough character. Everything happening around her is really awesome. But if you strip that away and just look at her, she’s kind of boring. This is a pitfall any writer can fall into with drama. Most of the heroes in these types of stories are reserved. The problem is, if you don’t write “reserved” just right, it can easily come across as boring. I think highlighting at least a character flaw can help this – that way you at least have the character fighting something internally. Unfortunately, I don’t think Kate had anything going on internally.

Still, this is really good writing and a worthy script to add to your reading list.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Awhile back we were talking about leading. By itself, leading helps keep the story moving. But there are ways you can turbocharge it to make it even more powerful. One of those ways is to lead towards something DANGEROUS. Let me explain. You can have a character say to Kate that tomorrow night is the going-away party for the Chief. That’s technically “leading,” because the reader now has another point in the script to get to. But it’s an almost empty lead. I mean, we know something’s coming, but it’s not that important. Check out how Sheridan uses leading. Kate goes into Mexico with the Homeland Security Team knowing that it’s going to be dangerous because the only way back is to go through border control on the highway. It’s mentioned several times that the Border Cops are going to leave a lane open for our team so they can get back into the U.S. quickly. But, of course, we know that that lane isn’t going to be open, and that something bad is going to happen to them while they wait in line. In other words, we’re being led to a dangerous situation instead of happy one. Once you make that promise to the reader that a dangerous situation is coming, I guarantee you they will stick around for it.