I had a giant screenwriting revelation this week.

Anybody who’s gone through a good revelatory moment knows that it’s exciting but also terrifying. Terrifying because any new revelation strips down at least part of your belief system. It forces you to rethink everything. And this one, this one I was sure I knew how to do right. Now, I’m not so sure.

How this came about is that I was reading a few screenplays for the contest and they were all really boring. Not bad, mind you. But boring. Bland. Lifeless.

What makes a script boring? A number of things. But the primary one is that the story is predictable. We’re always ahead of the writer. The reason so many writers, both amateur and professional, write these boring predictable scripts is because they map out the story from start to finish. They then go in, follow the map, and because the route has been so carefully planned ahead of time, there is no spontaneity to the story. There are no unexpected twists (except for blatantly manufactured ones – “the agent’s handler is actually the villain!”). There are no surprising developments. How could there be when you’ve constructed a series of events that are a carbon copy of events from movies we’ve already seen?

I began to think, what’s the problem here?

Why do I read so many scripts that have this issue? And why are writers so blind to it?

And here’s where my revelatory moment came.

It’s because too many writers know their ending before they start writing.

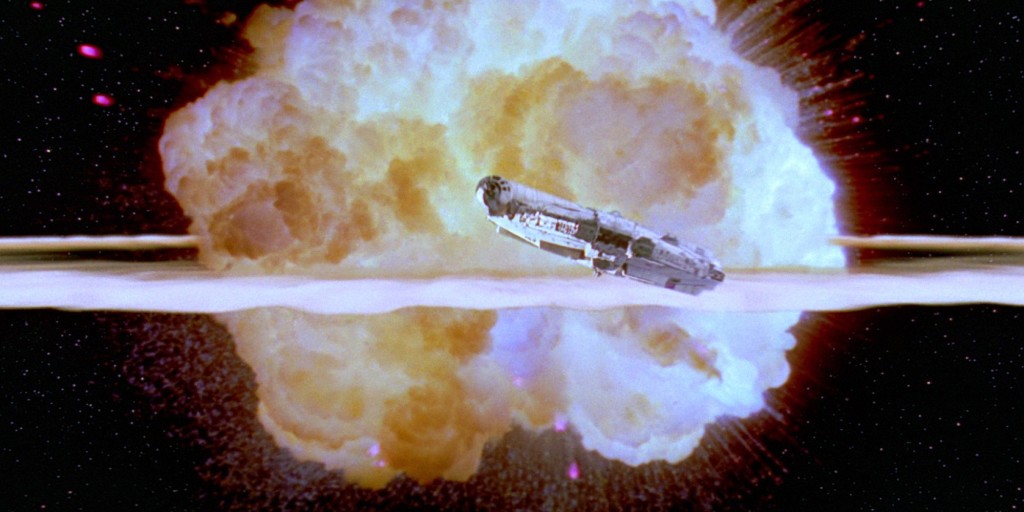

You’ve heard me espouse before not to start your screenplay until you know your ending. The advice sounds good in theory. If you don’t know where your script ends, how do you know where to place your characters in the meantime? Knowing your ending allows you to come up with a clean goal-driven narrative. Luke Skywalker blows up the Death Star. Okay. Now I just have to come up with the story that gets him to a point where he has the opportunity to blow up the Death Star.

However, here’s the catastrophic problem with knowing your ending before you begin.

If you know where you have to deliver your character, you will never put them into any situation that will seriously impede your ability to deliver them there.

For example, a couple of weeks ago, I reviewed a script called Video Nasty about a brother and sister who get stuck inside a horror movie. The script was okay. I think I gave it a low ‘worth the read.’ But it wasn’t memorable by any means. And a big reason for that is this problem. The writer knew, before he started writing the script, that the brother and sister were going to escape the movie and be okay at the end.

So let’s say, midway through writing the script, around the midpoint of the story, the writer thought to himself, “Man, it would be really great right here to kill off the sister. It works thematically and it will shock the audience.” But he can’t do that. He won’t do that. Why? Because he has it locked into his head that the brother and sister get out at the end. So, instead, he writes a scene where the killer corners the sister in a house and almost kills her but she gets away. The scene is average because it’s handicapped by that locked-in ending. We can’t put her in too much danger because then my ending is compromised!

Now let’s say the writer went into the script NOT KNOWING the brother and sister get out at the end. In that situation, he is more likely to follow his gut when writing. He’ll kill off the sister and figure it out later. Also, because his brain is open to any possibility, he may figure out a way to bring her back from the dead! If the brother and sister are stuck in a movie, and movies aren’t real life, then a death may not be a death. Now maybe he figures out a way to bring the sister back or maybe he doesn’t. The point is, he’s created a less predictable story this time around because he’s not beholden to that set path.

As I delved deeper into this, I realized it extended beyond the ending. If you figure out your midpoint ahead of time. If you come up with some major twist you want to happen at a certain page. You will now be writing towards those moments, and, without realizing it, creating predictable mini-narratives. Once you determine any outcome, you’re never going to write anything that steers you too far away from that outcome.

All of this led to the realization that, oh my god, knowing your ending is creating an endless stream of predictable screenplays! Even worse, any exercise that sets checkpoints in stone – such as outlining – is a creativity killer! They keep the script on the road when everybody knows the best moments always happen when you go off-road.

However, here’s why it’s not so simple. Not knowing anything that’s going to happen in your script is just as bad. It creates a different type of problem. Without outlines, writers lose steam around the 45-page mark. It’s hard to make something out of nothing for 110 pages straight. You need SOME direction or your script becomes a rambling mess.

I can’t stress that last point enough. The unstructured equivalent of the “bland predictable screenplay” is the “rambling unfocused mess of a screenplay.” If all you’re doing is writing whatever comes to mind in the moment, your script comes across as disjointed. Mank is a good example of this. It starts out about a guy trying to write a screenplay and ends up being a political film, likely because Jack Fincher thought, “This screenwriting storyline is fun but I want to go explore this other thing now.”

Which leads us to the obvious question – What do we do about this???

I have two options for you. It comes down to what type of writer you are. Do you need structure to operate or not?

If you’re comfortable writing without knowing how your story ends, or even where it’s going to be in thirty pages, go ahead and write that way. You’re way more likely to find interesting story directions than the restricted writer. Your script is going to be less predictable and, therefore, more compelling. However, you’re going to have to do twice as many rewrites as the structured screenwriter. That’s because your narrative is going to zig-zag so much that it’ll take more time to eliminate the ideas you came up with that don’t work. And for the ideas that do work, you’ll have to go back in your story and set them all up. For example, if, like in Parasite, you came up with this on-the-spot idea that another family was living in a secret basement in the house – you can’t just throw that one in there with no explanation. You’ll have to write in hints here and there that the basement exists so that its eventual reveal is a payoff (as opposed to one of those random doesn’t-make-sense-at-all reveals you see in so many amateur scripts).

If you’re a structure person and your beat-by-beat outline is your childhood blankie and you won’t dare start your script until you know your ending, that’s fine, too. You can continue to write this way. However, you have to embrace a different psychology when you write. When inspiration strikes, follow that inspiration, even if it goes against your outline. Also, and this is even more important – you must learn the art of painting your characters into corners that you have no idea how to get them out of. The reason this is so important is because your default style of writing is predictable. In the past, that’s what’s caused you to make sure there’s always an air conditioning vent right above the corner you’ve painted your character into. You’ve created the escape plan before you’ve written the scene. And when you do that, the reader gets this feeling that the outcome has already been decided. Which saps the life from a scene. You want them thinking the opposite. “Oh my God, how are they going to get out of this?” The only way to achieve this is if you genuinely have no idea how you’re going to save your character. If you take nothing else from this article, take that. If you become an expert at that skill, you’ll write tons of captivating scenes going forward in your career.

I’m curious to hear what your responses are to this realization because I definitely think a script has more energy when even the writer isn’t sure where the story is going next. Which makes sense. If they’re not sure, how can you possibly be?

Genre: Sci-Fi/Thriller

Premise: A memory dealer finds herself wrapped up in a murder she must prove she didn’t commit or else the city’s biggest crime lord will kill her.

About: Graham Moore burst onto the scene when his breakthrough screenplay, The Imitation Game, won a screenwriting Oscar! But that was six years ago, and while Moore has still worked steadily, he’s struggled to live up to that achievement. Hey, I’m not hatin’ on you, Graham. Just ask Christopher McQuarrie how easy it was to win an Oscar with his first big Hollywood script. Well, Moore is finally taking things into his own hands as he wrote this script, which was purchased in 2018, and will direct it.

Writer: Graham Moore

Details: 120 pages

The ‘memory’ concept.

They’ve been around for as long as people have written movies. When they go well, they go really well (Eternal Sunshine, Memento). And when they go bad, you wish *your* memory could be wiped. Anybody remember that Ben Affleck John Woo movie, Paycheck?

I read a lot of sci-fi memory-based concepts and I’ve learned you have to do three things well to pull them off.

1) You have to know the world/mythology back and forth – These scripts work best when the world feels like it’s been combed through. The vocabulary is second-nature. The process of how the memory conceit works is seamless. It doesn’t feel like a bunch of first draft choices but rather like this writer has lived in this universe for decades.

2) The execution cannot be messy – What I’ve found with these concepts is that they get messy quickly if you don’t stay on top of them. What I mean by that is, if you’re injecting a memory into someone’s brain, you have to think about how that actually works and what the rules are. How it affects them. How it affects the story. The more you know, the clearer you can keep the plot. But if you flippantly decide late in the script, “oh, I’ll also give the police chief a false memory” and you don’t really know how that connects to everything else, the reader will pick up on it. So these scripts need to be rewritten more than your average script to plug up all those holes.

3) They need to be clever – You need at least a couple of big clever plot developments when you’re working with something like memory distortion. The genre is built for it. Any memory anyone has can be false. That gives you so many avenues to manipulate the story in clever ways. Take advantage of it.

Did “Naked Is The Best Disguise” pass this test?

Let’s find out!

Ardis Varnado is a female memory dealer in near-future Chicago. Taking old memories out or injecting new memories is illegal. So you need to hire someone like Ardis to come by and do the process for you.

That’s how 50 year old banker Richard Fitzgerald meets Ardis. Fitzgerald is a geeky family man who’s always wanted to do something crazy. So Ardis is going to inject him with a memory of a woman sexually dominating him. Fitzgerald is embarrassed about the whole thing but for Ardis, it’s all in a day’s work.

Speaking of that work, Ardis commonly abuses her own product. Some nights she gets home, pulls out a few memories from her briefcase, and shoots them up. This is the problem with memory juicing – you do it enough and you start to lose an understanding of your true self. It’s like drug-addiction but worse. Because at least with drug addiction, there’s a chance you get back to who you once were.

Not long after Ardis leaves Fitzgerald, she learns he’s been shot dead. And she’s the prime suspect. When she goes back to her boss, it turns out he’s been killed too. Ardis realizes that she must clear her name by the end of the night or she’ll be done in by the cops or the city’s primary memory crime boss, Chinese billionaire, Wing.

Ardis teams up with an old friend, Mason Russell, who has some connections with the police. This allows the two to stay a step ahead of the cops all night as Ardis investigates what happened. She eventually discovers that Fitzgerald was a “courier.” He’d just been in China where he was injected with a memory to take back to the U.S., where it would then be extracted.

This confuses Ardis, since Fitzgerald had said this was his first memory injection. Mason floats the idea that they could’ve extracted the memory of him receiving the memory in China, so that he didn’t know he had it. Which is when we realize this is all way more complicated than we thought. When Ardis learns the China memory was also extracted, she realizes that their only way out of this nightmare is to find that memory – a memory so show-stopping it has the power to change everything.

“Naked” is a strong script because Graham is a strong writer.

And he mostly knocks down the three pins I talk about above. He knows his mythology well. The execution is solid. And there are several clever twists. The problem is these rules aren’t met nearly as convincingly in the second half of the script as the first. Which, I guess, makes sense. When you’re playing with memory in a story, it’s a bit like time travel. The more of it you do, the harder it is to keep everything clean.

I remember learning that lesson myself. I once wrote a time-travel script that had a lot of rules and even after re-writing 20+ times, I was still getting the same feedback – “This is confusing. There are too many rules.” I remember thinking, “No! You just don’t get it!” Lol. I think that’s a major step in every screenwriter’s career, when they stop blaming the readers and, instead, look at themselves. That experience taught me the importance of simplicity when dealing with complex concepts.

That doesn’t mean you can’t play around with the concept. But you have to realize that every additional use of your concept you inject into your script, it’s going to make your job harder. In “Naked,” once a memory is extracted from you, you can no longer remember it. You’re also getting injected with new memories, which you don’t know aren’t your memories. Within seconds, they work just like your own memories.

So if Ardis killed Fitzgerald and then had the memory erased, but then she was injected with the memory of meeting with her boss, which she hadn’t, you can begin to see how complicated it gets.

But to Moore’s credit, he never quite crosses over into the land of “Okay, now I’m fucking lost.” He’s good at explaining the rules and checking back in to let you know what’s going on. That means most of the memory developments were fun. Because now it’s a puzzle. And you’re trying to figure out which memories are real and which are fake, and how all of it fits into the murder.

Despite that, I don’t think Moore had as much fun with the concept as he could have.

When you’re talking about private memories, you’re talking about a level of darkness that doesn’t exist in the open. There are skeletons in everyone’s past, the kinds of things people don’t discuss. And I was waiting for a few of those to pop up. But all the memories were relatively tame. Even Fitzgerald’s sex memory was weak. He wanted to be dominated? You can hire someone to be at your doorstep in 15 minutes for that.

And that carried through to the final memory everyone was after. I was disappointed because the memory reveal works for the plot. But when you’re building up THE MEMORY OF ALL MEMORIES the whole movie, you’re hoping for something more than just a bow for the plot.

I’m being hard on this because I love concepts like this so much. My expectations are high. All things considered, Moore did a good job. This was definitely worth the read. It’s a lot better than the scripts I usually read that deal with this topic, that’s for sure. Curious to see what the finished product will look like.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Your daily reminder that when you have a strong concept like this, it is imperative you look for every opportunity to exploit it. Strong concepts are what give your script all the things other scripts don’t have. Take Fitzgerald’s sex memory desire. Like I said, he can get that with a prostitute. Which means you’re not exploiting your premise. If you’re exploiting your premise, the memory he asks for is something there’s no other way for him to experience.

Genre: Romantic Comedy

Premise: When the president of the United States heads to the G7 Conference in France, he’ll meet up with the new Prime Minister, who he had a one-night stand with at Oxford twenty years ago.

About: This script finished in the middle of the pack of last year’s Black List. Writer Pat Cunnane was a staff writer on Designated Survivor, which gave him some insight into how to write a president.

Writer: Pat Cunnane

Details: 117 pages

Romantic comedies are HOTTER than a pizza oven in Satan’s basement right now and I’m only expecting them to get hotter.

Since rom-coms relied solely on the star power of their leads, they weren’t able to survive the death of the movie star era. But then a new opportunity arose. The streamer! Streamers didn’t need movie stars to sell their rom-coms. All they needed were two good-looking people and a production that cost less than 15 million bucks. Which is why these little films have found a second life. But what the new generation of rom-coms hasn’t found yet is a good movie. Has there been one memorable rom-com in the last decade? Not to my knowledge. Maybe Affairs of State will be the first one.

Harry Baker Axton is the president of the United States. I’d like to tell you something specific about him but the script doesn’t provide anything in the way of a description of Harry. I guess I’ll just go with “generic presidential figure” in my head. Always a good idea to let the reader do the writing for you (PRO TIP – If you don’t tell us, we’ll make up our own version. And our own version probably won’t be what you had in mind).

Across the pond, we meet Ella Walker who, likewise, comes to us minus a character description. Ella is in the final days of her political race against the current prime minister. It’s a race she wins by the skin of her teeth, shocking the country and the world.

Back in the US, we learn that Axton has a secret. These two actually know each other! Axton was a teacher’s assistant at Oxford when Ella was attending school. The two got drunk one night and engaged in a one-night stand, a one-night stand Ella regretted immediately.

When Axton flies to France for the G7 summit, he reunites with Ella for the first time since that evening. Before we can see what’s going to happen between the two, we’re given the details of an elaborate problem in Yemen that Russia is making worse. This becomes our B-storyline. The Yemen Military Issue. In a romantic comedy.

Ella makes clear to Axton that nobody can find out what happened at Oxford as it would mean the US and Britain could never do a deal again without both countries assuming it was done due to their tryst. Or something like that.

The problem is that Axton really likes Ella. And over the next 48 hours, he keeps sneaking into rooms she’s in and making his case why they should be together. Ella eventually buckles because she sort of likes him. Then the worst possible thing happens. Someone leaks the Oxford affair to the press! This means that one of our esteemed leaders will have to step down from their position. Who will it be? And does this mean our lukewarm non-affair is over for good?

Welcome, my friends, to the world’s most serious romantic comedy!

If you’ve ever wanted a rom-com that centered around the military conflict in Yemen, look no further. I’ve found your script.

Man was this script frustrating.

The whole time I was reading it, I was trying to figure what kind of movie it was. The setup implied a romantic comedy. But the Yemen conflict coated the whole thing in this drab seriousness.

The one thing I know about rom-coms is that there has to be sexual tension between the leads. So I was baffled to find out there was none. Ella straight up hates Axton. There’s never a happy moment between the two. Which was bizarre since, during a couple of moments, she kisses Axton.

All I could think was, “Where is this coming from? You haven’t shown an ounce of interest in this guy for the last 40 pages.”

The script picks up once we get to France because, finally, we have some kind of structure to the movie. They’re going to be stuck working together at the G7 conference for the next 48 hours. That gave us a ticking clock. And because the two of them were always surrounded by their handlers, it gave them very little time to sneak away and be together. That’s always a strong scene set-up, when two people are trying to talk but barely have any time to do so. So this section was readable.

But everything else was straight up disappointing.

I had a major problem with the stakes in the movie, which is Axton’s and Ella’s former hook-up. If the press learns about it, the ability for their two countries to work together is compromised since they’d be making deals for each other and not their people.

Sometimes a set of stakes can work on a technical level yet the audience still doesn’t care. That’s how I’d characterize these stakes. Yeah, sure, their Oxford tryst could “compromise” honest negotiations between the countries. But did I really care about this? Did it worry me? Not in the slightest. If the reader isn’t worried, your stakes are weak, whether they logically work or not.

Stakes is one of those aspects of storytelling you don’t want to lie to yourself about. If you don’t get the stakes right, the audience never feels fear or hope. They never feel fear that anything truly bad is going to happen. And they never feel hope that anything truly good is going to happen. And without fear and hope, the reader is reading from a neutral position the whole time. Nothing in the story can ever affect them in an emotional way.

But there’s a bigger problem here.

The script was never going to work because it’s built on a weak concept.

When you’re setting up a romantic comedy, it works best when there are differences between the main characters. In fact, the more severe the differences, the more interesting the dynamic tends to be. Rom-coms also work best when there’s a power imbalance. This actually works well for any movie team-up. The imbalance is where you get the contrast. The contrast is where you get the conflict. The conflict is where you get the drama. The drama is where you get the entertainment.

Pretty Woman. Notting Hill. Meet the Parents. The Proposal.

Look at the contrast between the characters in all these movies. Look at the power imbalance. It’s severe in all four flicks, right?

Now let’s look at Affairs of State. Two characters. Both leaders of their countries. Both on the same level in pretty much every way. There are very few differences to work with here.

Sure, you get some conflict from the fact that they have to sneak around. But a romantic comedy, if indeed that’s what this is, needs to work at the character level. You need to be able to put your two characters in a room together without anything else going on and they’re interesting together. This script didn’t have that. It was only able to create these momentary pockets of interesting interactions.

I’m frustrated because rom-coms are making this huge comeback and, yet, nobody knows how to write them anymore. I get the feeling this writer has watched five rom-coms his entire life. That’s the only thing that explains why he thought a Yemen subplot would be a good idea.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you’re writing a movie about characters in a specific job – like politics, like business, like the medical field – a common mistake is for your characters to only talk about that world. For example, if you’re writing about doctors, the mistake would be for your doctors to only talk about surgeries, patients, or medical procedures. That’s not real life. In real life, when people get away from work, they talk about anything but work. How their sports team sucks, their favorite hobby, friends, TV shows, their kids, whatever. I found it bizarre that the only thing Axton and Ella talked about this whole script was politics. It just solidified the script as a bland one-note experience.

Originally, I was going to do a “Mank” script-to-screen review but after spending an hour with the film and realizing Fincher hadn’t changed a word from the disastrous screenplay, that the review would’ve been a bloodletting and sent everyone into the week feeling miserable.

Conversely, my weekly Friday night whipping boy, The Mandalorian, had one of its best episodes. Which set up an interesting question. How is it that someone who is so good can make something so bad, while something so bad can manage an episode so good?

Let’s start with Mank.

I mean… I’m just going to say it. This movie was a disaster.

Now you may say, “But Carson! Look at the Rotten Tomato score! It’s high!” A couple of things. Critics love David Fincher. And rightly so. He’s one of our best directors, hands down. But for that reason, their default setting for every Fincher film is a thumbs up. I’m not sure they’d be able to give Fincher a negative review if they tried. Also, what critics are scoring here is not the movie as a whole. They’re scoring the direction. They love how Fincher has recreated a 1940s film to chronicle what is, arguably, the best movie ever made

But as a story?

AS A STORY!????

This is one of the worst scripts of the year.

With almost every bad script, lack of focus is a problem. And that’s exactly what I’m seeing here.

A good movie has a focused narrative. Somewhere in the first act – preferably as soon as possible – you explain to the audience what the problem is, which necessitates that your protagonist solve that problem. This creates the hero’s goal and the rest of the movie follows his struggle to achieve that goal.

In the recent hit film, The Invisible Man, the problem is that the heroine’s evil dead husband has found a way to come back to life and torture her. The goal, then, is to prove that this is happening then defeat him. You can break almost every good movie down into this formula.

The thing about Mank is that it PRETENDS to incorporate a problem, but it’s a sham. A lie. A misdirect. The movie starts with Mankiewicz being placed in a hotel room and told by a studio suit that he has 90 days to write the screenplay for Citizen Kane.

Except the movie then proceeds to COMPLETELY ABANDON THIS SETUP. The next 50 on-screen minutes contain scenes that literally have nothing to do with Mank’s pursuit of this goal. They are, rather, flashbacks of him hanging out on movie sets and in studios. And whenever we do manage to get back to that room, we get conversations between him and his typist that – how do I put this nicely – have nothing to do with fucking anything.

It takes until HALFWAY THROUGH THE MOVIE before we get a scene of our suit returning to Mank’s drab hotel and saying, “You only have 10 days left! And you haven’t even finished the first act!” Normally, an escalation like this would pump life into the movie. But everybody in Mank treats the goal with such a lack of importance that we don’t feel anything.

You’re only ever as good as a) your concept and b) your execution. If either of those things is weak, you cannot recover. I would argue that Mank is weak in both areas. I don’t even understand what the concept of Mank is! Mank needs to write Citizen Kane, which is followed by a movie that has nothing to do with Mank writing Citizen Kane? Anyway, this is how a great filmmaker can make a bad movie. Latch onto a concept that wasn’t any good in the first place and then abandon all pretense of a hero resolving a problem.

I mean the scenes in Mank are so aggressively disconnected from one another you must draw on an insane amount of concentration to keep track of what’s going on.

There was this scene where Mank and Marion are walking around the Hearst Castle babbling about the most inane things, and I thought to myself, “What is this scene about? How is it pushing the story forward? Where is the conflict? Why is it important that this scene exists?” It seems like all but a few scenes fail to answer these questions.

I remember one good scene in the entire first half. It’s the scene where Mank and his brother come to MGM and studio head Louis B. Mayer a) gives them a tour while explaining to them the rules that dictate MGM before b) making a speech to the entire MGM staff that he’s cutting their salaries by half.

Why does this scene work while all the others don’t? Because it incorporates the only two scenarios in the movie that we actually understand. We understand when someone gives someone else a tour of their domain and explains the rules of the house. We understand the concept of a man standing in front of his employees and having to give them bad news. For once in the movie, it was actually CLEAR what was going on.

I don’t have any clarity on why Mank and Marion are stumbling around Hearst’s house mumbling about shit that doesn’t have anything to do with the story.

The failure of Mank comes down to the ignorance of one simple reality – Decide what your movie is about or face the consequences.

Meanwhile, in a galaxy far far away, a certain show has decided that it actually wants to become entertaining again.

The problem with the Mandalorian is that it had eased into this relaxed storytelling style by which Mando was assigned some directive which he then had all the time in the world to achieve and, even if it didn’t work out, it wasn’t a big deal. In other words, each episode had a goal. But both the stakes and urgency regarding that goal were low.

This is why the latest episode of Baby Yoda, err, I mean Mandalorian, was so good. Directed by Robert Rodriquez, we got our first full GSU episode in Mandalorian history.

Goal – Protect Baby Yoda while he sits on the sacred rock to see if a Jedi teacher arrives.

Stakes – Losing Baby Yoda (Darth Gideon has arrived to kidnap him)

Urgency – The onslaught of storm troopers to retrieve Baby Yoda starts and never stops the whole episode.

That’s what stood out to me most about the episode. It contained an urgency that no other episode up until this point had. Remember, that’s what made the original two Star Wars movies so good. Urgency. Darth Vader relentlessly pursuing Luke Skywalker and the rest of the gang from the start of the movies to the finish.

It’s something I felt, before the show even began, it would struggle with. Could Star Wars sit inside those slow moments? It’s been able to every once in a while. I like the little scenes with Mando and Baby Yoda hanging out in his ship together. But mostly these moments have been a dud. In order for slow moments to work, the character writing must be exceptional. That’s because if we like a character, we don’t need the plot to be “go go go.” And, unfortunately, Mandalorian has had a lot of dud characters.

But the last two episodes are changing that. This Ashoka Jedi chick is pretty badass. And Boba Fett (who arrived this week) is VERY badass. I get a little weak in the knees imagining all three of them teaming up together, Avengers style (let’s not forget that Jon Favreau began the Avengers universe with Iron Man – so he knows a thing or two about team-ups).

But the bigger takeaway from these last two weeks of Mandalorian is that the show works better when the plot is ramped up. There seemed to be more purpose in both of these episodes – from Mando needing to find Ashoka to Boba Fett needing his armor and the Empire trying to kidnap Baby Yoda – and that’s what’s been missing in the Mandalorian so far.

A lot of this harkens back to an age-old screenwriting problem, which is that the idea you originally conceive isn’t always the idea you should go with. My guess is that Favreau originally conceived of this show as a straight Western. That’s why it was so slow. He liked the idea of his character lazily strolling into a new town, hanging out, chatting, building up a little suspense, then resolving whatever villain-of-the-weak problem the town/planet had.

But I think the Star Wars DNA requires importance and urgency. We see that in these last two episodes. Last week was the importance of finding a Jedi to take Baby Yoda. And this week’s episode was all about the urgent nature of holding off the Empire as they tried to kidnap Baby Yoda.

So if I could tell Favreau anything, it would be that you’re good with the G(oal). But you need to embrace the S and the U. The S(takes) and the U(urgency) are what made these last two episodes of the show two of the best.

22 screenplays on The Last Great Screenplay Contest bubble are duking it for a slot in the finals. Congratulations to Colin O’Brien, whose script, “Our Hero,” won the first Contest Showdown. And then last week, Kevin Revie won his showdown with the ultra-buzzy “Bad Influence.” That makes this showdown our third week, and it is once again up to you to read as much as you can of each screenplay and vote for your favorite in the comments!

It’s IMPORTANT THAT YOU VOTE. A screenwriter’s career may be on the line. As well as my producing career. Votes are due in the Comments Section by Sunday evening at 11:59pm Pacific Time. The script with the most votes moves on to the Super Showdown.

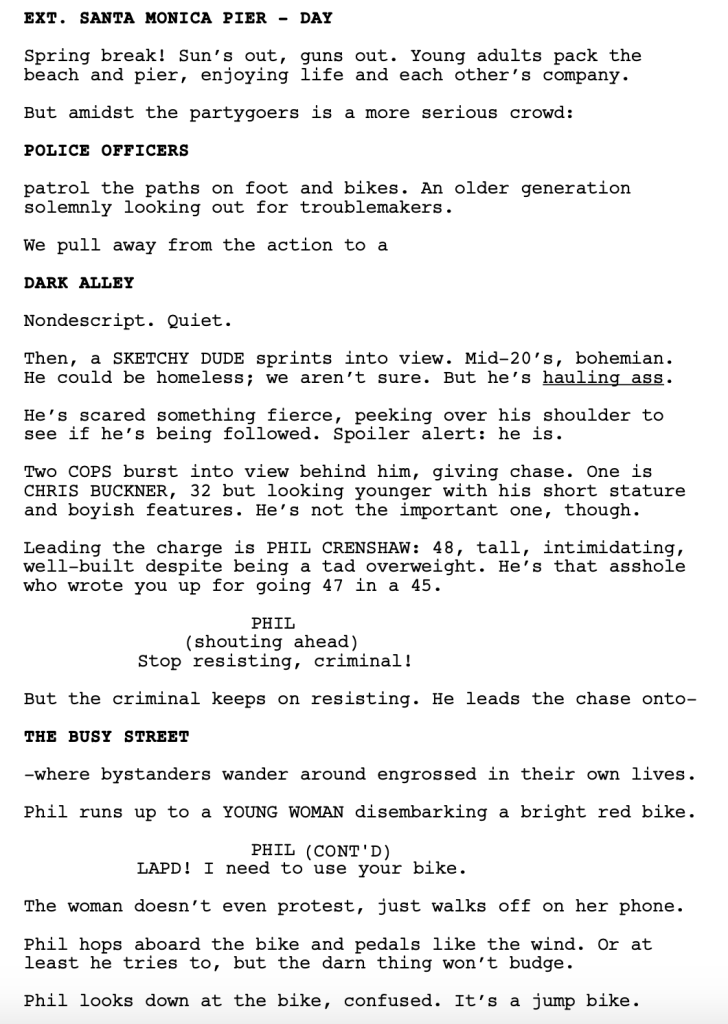

Title: Get Woke

Genre: Buddy-comedy

Logline: An old-school police officer joins forces with his tech-savvy teenage daughter to crack the case of a social media influencer’s cyber stalker.

Title: The Living Conditions

Genre: Horror/Romance

Logline:With her boyfriend’s help, a young woman going through a monstrous transformation searches for the one responsible in hopes of reversing the effects, all while evading capture and resisting her newly acquired “urges”.

Title: Unchained

Genre: Action

Logline: Two fallen out sister-soldiers must reunite and reconcile as they fight their way through a train of mercenaries to reclaim a mysterious WMD-classified object that drove them apart — before the ride reaches its destination.

Title: Shalloween

Genre: Comedic Slasher

Logline: When all the hottest girls in a small town get slaughtered by a masked serial killer, a social media influencer obsesses over why she’s not hot enough to murder, and starts looking for an alternate explanation for the killings.

Title: Archer

Genre: War

Logline: 1415 — As the English army marches towards doom in the greatest battle of the medieval age, a young archer seeks redemption for his past under the cruel tutelage of his ruthless and invincible sergeant. A medieval FURY meets PLATOON.