Search Results for: day shift

I suspect most of you will assume I didn’t like The Bubble. Most of you would be correct. However, I don’t think The Bubble is as bad as some people are saying it is. Once it hits its groove and understands what it is, it’s not bad. The problem is it takes too long to get there.

I suspect most of you will assume I didn’t like The Bubble. Most of you would be correct. However, I don’t think The Bubble is as bad as some people are saying it is. Once it hits its groove and understands what it is, it’s not bad. The problem is it takes too long to get there.

The movie starts off as a commentary on the pandemic, which doesn’t work because while the intention was to parody something we all went through and therefore be “relatable,” it only parodies a unique subset of the pandemic – that of trying to make a movie.

I don’t know anyone who had the problem of being quarantined in a hotel with a bunch of charismatic people while they got paid millions of dollars. It was too specific of a parody so many of the pandemic jokes didn’t work. For example, I didn’t have to get tested every other day during the pandemic. So that’s not funny to me.

However, once the narrative shifts to the studio trapping the actors until they finish their movie, the movie actually gets kind of funny. For example, there’s this big climactic scene where the actors make a run for it and get into a helicopter, which is their only way to freedom.

In every action movie, getting in a helicopter and flying off while being attacked from all sides is a foregone conclusion. But in this movie, where a lone actor knows how to fly helicopters via his 8 movie-prep lessons, the team rises off the ground before they find out that the actor has only ever learned how to go up and down. So the big climactic moment is simply: can he figure out how to go forward so they can leave?

Despite its weaknesses, it’s a movie worth discussing if only because Judd Apatow is the biggest comedy director in the world. So if Judd Apatow miscalculates, it’s worth asking why, so we can learn from it.

Judd made two risky choices that may have done The Bubble in. The first is that he abandoned any emotional through-line in the screenplay, which has been one of his staples. For example, in his last film, The King of Stanten Island, there’s this really deep surrogate father-son relationship between the main character and his mom’s new boyfriend.

As I’ve argued many times here on the site, if we don’t feel any emotional connection to the characters, we don’t feel like they’re real. So when they get into trouble, we don’t fear for them. And without that fear, every joke that highlights their misfortunes is paper-thin, since we know it doesn’t matter.

Judd has been forthright about this. In his Barstool Sports interview, he said that this was a new challenge for him, writing a pure comedy, where all you care about is the jokes. I got the sense that he began freaking out about this choice towards the end of the movie as the sudden third-act focus on character emotion felt like an overcorrection, an attempt to remedy his mistakes from earlier.

The other mistake Judd made was he didn’t have a main character. I remember about 30 minutes into the movie feeling like I’d met 50 people and knew none of them. We’re bouncing around so much that we never get attached to anyone. If you look at Judd’s most popular movies – films like The 40 Year Old Virgin, Knocked Up, even Trainwreck – they’re almost aggressively one-character movies.

When you focus on one character, you can dive into who that person is, what makes them tick, what their flaws are, what their vices are, what their relationships are like. And we just didn’t get any of that in The Bubble.

There’s a moment late in the script where the closest thing that Judd has to a main character, Carol (Karen Gillan), seeks out help from Sean Knox (Keegan-Michael Key). In the scene, Carol, who’s losing her mind, wants to know how Sean, who’s a major movie star, is able to stay so positive.

This was about 80 pages into the screenplay, mind you, and it was THE FIRST TIME I was aware that Sean Knox was a major movie star. I had no idea. That was par for the course here. This choice to follow everyone instead of someone prevented us from knowing anyone.

Here’s a tip. Whenever you’re trying to decide who your main character should be, ask yourself who has the most to lose? Who has the most on the line? That person should probably be your hero.

In Juno, it isn’t Juno’s boyfriend who has the most on the line. It isn’t her parents. It isn’t her friend. It isn’t even the family she’s going to give the baby to. It’s her. She has the most on the line. She’s pregnant. What she does affects, literally, the rest of her life.

To that end, the main character in The Bubble probably should’ve been the director, Darren, played by Fred Armisen. He seemed to have the most to lose. This was his big studio shot and it just happened to come at the most restrictive time for movie production in history.

Trying to make a good movie under those conditions must have felt like an insurmountable task. But since we only kind of knew Darren, we never felt any compassion when the movie began slipping through his fingers.

Comedy continues to be an extremely frustrating genre. How is that a genre whose faults are the easiest to dissect is also the hardest to execute?

Luckily, The Bubble isn’t the only new thing that dropped last week. We also got a new Marvel series, Moon Knight. I’d say, of the five Marvel shows that have come out so far – Wandavision, Falcon and Winter Soldier, Hawkeye, Loki, and now this – it’s probably the most anticipated considering it has the best actor and the least known story. Unlike the other shows, Moon Knight is a brand new character we haven’t met before. It’s exciting having a complete unknown for once.

The thing I will give Marvel is that between Wandavision, Loki, and now this, they are taking chances. I can’t sit here and complain that Hollywood never takes risks then ignore it when they do.

I have a lot of admiration for Marvel using these shows as a testing ground for unique storytelling, and not just making them bite-sized versions of their movies. Well, I guess Hawkeye and Winter Soldier are bite-sized versions. But three of these shows are still unique. And Moon Knight may be the most unique of all.

At the center of the story is this giant mystery. This museum worker, Marc, constantly blacks out, missing huge chunks of his life, which results in a daily routine where he’s just trying to get up to speed half the time. For example, a female co-worker asks him if they’re still on for their date Friday night. Except Marc does not remember asking this girl out.

These missing chunks of time are getting more volatile, though. Marc will find himself in the middle of a small village in a completely different country surrounded by cult-members and have no idea how he got there. When they sense Marc is an intruder, they attack him, only for Marc to black out, and when he regains consciousness, 20 people around him have been violently killed, and his hands are dripping with blood. This cult leader, Arthur, wants something Marc has, an Egyptian gold scarab (our macguffin), and he’ll do anything to get it.

The pilot is a great reminder of how influential POV (point-of-view) is to a story. Take The Bubble, for instance. The POV was 20 different characters. We saw the unfolding drama through enough eyes to get a 10,000 feet high look at what was happening.

Here, the POV is just one person, Marc. And because we’re in his head with him when these chunks of time keep disappearing, we feel the same fear he does. I remember, at one point, literally wondering, “Good God. Is this what being crazy feels like? Where you’re a slave to this illogical sequence of events that are constantly changing?” I don’t have that feeling without Marc’s singular POV.

Imagine if Moon Knight was told like The Bubble, where we saw Marc’s situation through ten other people. All that fear would be gone. Cause we’d know exactly what was happening. So POV is something every writer should consider when writing a script. WHO has the POV and HOW MANY people have the POV will have a dramatic effect on character, plot, theme, how you build suspense, where you find your conflict, everything.

The question will be, can Moon Knight keep its death-defying pace up? Presumably, our main mystery will be solved going forward. They already kind of answer it at the end of this episode. So will they simply move the mystery over to his Egyptian roots and what this Arthur villain is after? Or will they just have Moon Knight solving crime, a la Batman?

It’d be a shame if that were the case but this has been my issue with the 6-8 episode format, in general. It’s not quite a TV show. It’s not quite a movie. So nobody really knows what to do with it. We’re in that experimental phase and, so far, I’m not sure I’d call the phase a success. The only high-profile show I’ve seen nail it so far has been Peacemaker.

But I’m rooting for Moon Knight. It’s probably one of the coolest superhero costumes I’ve ever seen. And who doesn’t want to see more Oscar Isaac? Have you seen either Moon Knight or The Bubble? Let me know what you think!

I don’t think there’s ever been a time in my life where I’ve understood the movie industry less. It used to be that you’d buy a script, make the movie, release the movie, and if it did well, the movie was celebrated and everyone associated with it benefitted. If it did poorly, the movie was mocked and everyone associated with it got docked a few Hollywood credits.

These days, who knows what’s going on. There is a freaking Leonardo DiCaprio movie that can be seen over on Netflix right now *FOR FREE*. And yet, as of yesterday, more people would rather watch a film nobody’s heard of called “Stay Close,” which may or may not be a sequel to another movie nobody’s heard of called, “The Stranger.”

You’ve got an Academy Award winning screenwriter who just debuted a movie over on Amazon Prime, also for free, that has such a low profile that, up until yesterday, I thought it was called, “Keeping up With the Ricardo’s” (it’s actually titled “Being the Ricardos”). The industry has been flipped on its head.

This weekend, Hollywood debuted one wide-release film, a female ensemble spy flick called, “The 355.” Had they simply added a decimal after the “3,” they would’ve predicted its first week box office (4 million). It’s a telling moment for the industry, which just a couple of weeks ago, saw a movie land the third highest box office opening of all time in Spider-Man.

The message audiences are sending is clear: “Unless it’s got capes in it, we don’t want it.” When your clientele tells you they no longer like the product you’re giving them, you have to adjust.

One of things that Hollywood has always been good at is marketing. They know how to market anything, even serious films. They’ve learned that if they position a film late in the year and get some key critics to call it incredible, then promote a great performance or great writing or outstanding directing, and throw up a few “For Your Consideration” ads, they can influence enough people into believing it’s a ‘must-see’ experience.

To their credit, the system has helped a lot of good films that, otherwise, wouldn’t have been noticed. I’ll never forget how Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire was originally going to be a straight-to-DVD release until they decided to position it as an Oscar contender. Audiences then fell in love with it.

But this system has also promoted a lot of weak films. Nomadland is a good example. It’s not a good movie unless you’re the type of moviegoer who can have an in-depth conversation about the French New Wave movement. But the machine had to promote something and there weren’t any good “somethings” so they went with Nomadland.

This seems to be happening more and more lately.

Mank, Minari, Sound of Metal, Marriage Story, Vice, Roma, The Post, Ladybird, Call Me By Your Name, Darkest Hour, Manchester by the Sea, Phantom Thread, Fences, Moonlight, Brooklyn, and the list goes on. These are boring-to-decent movies that were overhyped enough that they attained a higher reputation than they deserved.

Now I’m sure some of you are saying, “Carson. You’re wrong! I liked [insert title from movies listed above]!” I’m not saying nobody liked these movies. I loved Parasite. I thought it was a great film. But I’m not going to argue with my non-industry friends when they say, “I don’t care how good it’s supposed to be. I have no interest in watching a Korean movie with sub-titles about class warfare.” General audiences don’t care about these films and the reason that matters in 2022 is that the industry is shifting and serious movies will be left behind if they don’t change their strategy.

The Golden Globes isn’t getting televised this year. AFI is postponed. Same with Critics Choice. Palm Springs is canceled. And The Academy Awards itself, because it’s been promoting weak films for the last half-decade, keeps losing viewers. The system doesn’t work anymore. So what do they need to do?

They need to do the indie version of what Marvel did. Marvel realized that they could expand their market if they cannibalized other genres. They’d give you a big tentpole summer movie experience along with some comedy. Along with a buddy cop film. Along with a spy movie. This is what the indie/Oscar movie market needs to do in order to survive. Unless they’re okay with 20,000 views on Amazon Prime.

The new strategy – give us adult movies that actually serve to entertain rather than try to win awards. Have you ever been to a bar and seen the guy who’s trying to be cool next to the guy who actually is cool? There’s a false bravado to the poser. There’s an underlying need to be liked. There’s a fakeness to his act that everybody sees through. That’s what movies that are trying to win Oscars come off like. They remind us of the guy at the bar who’s trying to be cool. We can all see that there’s nothing beyond the exterior.

If you want serious movies to be big again and to compete with superhero movies and to start making more than 30 million dollars, you need them to be GOOD MOVIES FIRST and awards contenders second.

The prototypical version of this is Silence of the Lambs. A serious movie that cared about entertaining us first and winning critics over second. The Wolf of Wall Street is another good example. Life of Pi, District 9, Slumdog Millionaire, The Departed, Gladiator, American Beauty, The Sixth Sense, Saving Private Ryan. The common denominator between all of these films was that they were serious adult films that prioritized entertaining people rather than preaching to them or trying to win a statue.

These days we get Promising Young Woman. And don’t get me wrong. I loved that script. But I’ve never met anyone outside of Hollywood circles who’s even heard of that movie, much less seen it. They just don’t care. And if the industry wants these people to care, get off of your own self-absorbed asses and start entertaining us. Make a movie that’s good. You have the capability to do both. You don’t have to bore us to death with Moonlight to win awards AND make money.

So like they always say: “What are you going to do about it, Carson?” Keep sitting around and complaining on your little blog? Or are you going to try and change it?

I’m going to change it.

As you know, I have my Fabulous First Act Contest coming up. Starting March 1st, I’m going to guide you through writing the first act of a new screenplay. The idea is that a lot of people are afraid of starting a screenplay because they have so much trouble finishing them. With this contest, all you have to do is write a first act. And, even better, I’m going to be coaching you through writing that first act. So you’re for sure going to finish and, if you want, enter it into my contest (details on entering will be published on April 1).

Anyway, since your chances of winning go up exponentially with a better concept, I want you to have the best concept possible ready by March 1. I’ve been seeing all types of concepts via my logline service (just $25! carsonreeves1@gmail.com) and I keep seeing similar mistakes being made over and over again. So here are five tips you can focus on for a better concept.

1) Make sure it’s a movie you would go and see – I can’t tell you how many writers send me ho-hum loglines and I’ve asked them, “Would you go see your movie?” And they always say, “Of course I would!” I would then ask them if they’ve seen a specific recent movie that’s similar to theirs. These are usually movies that have bombed because, again, they’re based off of weak concepts. Without hesitation, they say, “No.” “Well, why not?” I ask. “I don’t know. It just didn’t look interesting.” I then wait for them to understand the ramifications of what they’ve just said. But they never get it. They’re under the impression that, even though their idea is similar to a movie that nobody wanted to see, their version of the idea is, somehow, special, and people will want to see it. If you have no interest in paying to see movies similar to the one you’re writing, that’s a good indication you’re writing an idea people won’t be interested in.

2) Strange Attractor – I’ve been reading a lot of loglines lately without a “strange attractor.” The strange attractor is the element of your logline that makes it special, that makes it unlike other movies out there. Some people might even define it as “the hook.” Here’s an example of two loglines in the same genre. One without a strange attractor and one with. “After hearing rumors of zombies in town, a farming family holes up in their house for the night.” “A family must learn to live in complete silence after the world has been taken over by aliens that hunt through sound.” Zombies alone are not a strange attractor just as aliens alone are not a strange attractor. You need that extra element – hunting through sound, a family that must exist in silence – to make it a true strange attractor. The strange attractor is, I’d say, a necessity in a logline. It’s hard to get excited about a logline without one.

3) A character can be a strange attractor – Not all of us are interested in writing genre movies. Which is fine. But if you’re not writing genre movies, then you better have an amazing character who sounds interesting in a logline. They, then, become the strange attractor. “Alan Turing, an autistic gay man who would go on to become the father of the general-purpose computer and artificial intelligence, attempts to decode the mythical “Enigma” machine that the German army used to send encrypted messages during World War 2.”

4) Make sure there’s a healthy dose of conflict in your concept – Without conflict, a concept is just an idea. The conflict is what makes it a movie. So, for example, if I said to you I have an idea about a guy who realizes he’s a computer generated character in a video game, that’s still not a movie idea because you haven’t introduced the conflict yet. Now if you tell me that a computer generated character realizes he’s in a video game, starts to take over the game, forcing the game creators to try and kill him (Free Guy), now you’re forming an actual idea. The conflict is the bridge that helps the concept cross over from just an idea to an actual movie.

5) Be as specific as possible – I’d say that, roughly, one-third of the loglines I receive end with a general directionless phrase. “…until she doesn’t know what’s real and what isn’t.” “…causing him to question his life.” “…begins to see that not everything is what it appears to be.” These scripts almost always fall apart because there is no defined goal for the main character. They’re not trying to solve a murder. Or attempting to graduate college. Or trying to win over the guy of their dreams. A logline needs that clear defined path for the main character for it to sound enticing. Like above, with The Imitation Game. Alan Turning is trying to decode a machine to stop the Germans in World War 2. That’s so much better than, “Alan Turing attempts to decode the German Enigma machine, discovering along the way that, in war, there are no clear-cut answers.” Do you see how wishy-washy and generalized that ending is? That’s what we want to avoid.

I’ll have more conceptual tips for you as we get closer to the March 1. In the meantime, run with these!

Okay, it’s time for me to be… how to I put this nicely?

Parental.

I still love you but I have to teach you a couple of lessons.

I’ve noticed a good chunk of excuse-making in the comments section about why writers aren’t keeping up.

One of the biggest reasons is: Not enough time.

My response to that?

B.S.

And I can hear your resistance already. The anger is bubbling. You can’t wait to get down in that comments section and explain to me why YOUR situation is DIFFERENT from everyone else’s and how you actually truly seriously don’t have enough time to get your pages written.

B.S.

B.S. with a capital B and a capital S.

The only way you don’t have enough time to finish your pages is if there is an anti-screenwriting terrorist in your home pointing a gun at your head all 24 hours of the day and telling you that if you write anything, he’ll shoot you.

Unless that is going on, you have time.

If you are operating by the 2-Week screenwriting principle of not judging your writing, you can write 8 pages in 2 to 3 hours.

If you’re still convinced that you don’t have enough time, post every hour of your day and what you were doing during that hour in the comments section. I’m certain that the intelligent Scriptshadow community can help you rearrange some things to find two hours to write.

And if your excuse is that, sure, you do have the time, but you’re stuck and you don’t know what to write next – KEEP WRITING ANYWAY. I don’t care if you write a redundant scene or a scene that feels pointless. As long as you keep writing! Because when you write, you’re more likely to come up with ideas, and when you come up with ideas, you’ll have reason to keep writing.

“But… but… but… but…”

No buts. You know it’s true. You have time to write. Now stop making excuses and just do it.

On to something I’ve noticed a few of you having trouble with – dialogue.

Here’s the dirty little secret about dialogue.

Are you ready?

DON’T WORRY ABOUT DIALOGUE.

That’s it.

That’s the only thing you have to know about dialogue at this moment.

Why? Because there’s never been a script where more than 10% of the dialogue from the first draft made it into the final movie.

Dialogue is the most re-shaped component of a script and that’s because a) it’s easy to rewrite, and b) the more you learn about your characters over the course of a project, the better you understand what they’d say and how they’d say it. Not to mention plots are constantly evolving in rewrites, which means a lot of scenes are getting chopped, which means all those hours you spent obsessively slaving over that dialogue turned out to be for nothing cause the scenes no longer exist.

How insignificant is dialogue in the grand scheme of things? Remember how we talked about the Safdie Brothers writing 160 drafts of Uncut Gems?

Even WITH THOSE 160 drafts, they still did scripted takes AND “say whatever you want” takes with their actors. In other words, they knew that dialogue, while important, isn’t as important as your actors believing in and emotionally connecting with what they say. So after ten years of rewriting a script to death, the finished product still consisted of a ton of dialogue literally made up on the spot.

Yes, everyone, I understand that the Safdie Brothers are writer-directors and don’t need their dialogue to shine on the page. But still: dialogue should be one of the last things in the script you perfect. Once you’ve got your structure down (which usually takes about 6-7 drafts) and you therefore know you won’t be cutting many more scenes, that’s when your focus is going to shift to dialogue.

In the meantime, there’s two types of dialogue you should be writing in your first draft. Functional or fun. Functional dialogue when you’ve got exposition to convey to the writer. And fun for everything else.

So if you have a scene like in Jurassic Park where the characters are explaining the rules of the dinosaurs or how the theme park works, just get that dialogue down. It doesn’t have to be entertaining. You’ll make it entertaining in future drafts. Right now, it doesn’t matter if it’s dryer than sand. You just need to get it down.

And if you have a scene where two characters with some sexual chemistry are on their way to the next big set piece, have fun with their dialogue. Be outrageous, witty, silly, clumsy. You’re not trying to hit a home run your first at-bat. You’re trying to get a general feel for who these people are and the things they might say. These scenes can be twice as long as they’ll end up being in the final draft because you’re in exploratory mode.

With that said, I know that writing a good dialogue scene makes you feel good. And when you feel good, you want to write more.

So here are a couple of tips. One, try to have at least one dialogue-friendly character in your script, someone who likes to talk, has a lot of opinions, is clever, is funny, or all of the above (think Tony Stark, Harley Quinn, Oscar Isaac’s character in Ex Machina). Just having that character around will up the quality of your dialogue 30% without you having to do anything.

From there, look to dramatize scenes. Create some element of conflict within the scene. That conflict will force your characters to interact with dialogue that’s more fun to listen to.

For example, here are two scenes. You tell me which one is more likely to result in good dialogue.

The objective of the scene is to set up a pandemic virus that’s emerging so that the audience understands it for plot reasons we’ll explore as the movie goes on.

In our first version of the scene, Joe tells Sara why the virus is so dangerous. Sara, eager to learn, asks a lot of questions. “Where did the virus start?” “How many people have died so far?” Joe answers all the questions and when he’s finished explaining everything, Sara thanks him.

We’ve achieved what we’ve set out to do. The audience now understands the virus at the center of the movie.

Now here’s a second version of the scene. In this version, Joe and Sara have two different mindsets about the virus. Joe gets a lot of his news from conspiracy websites. He’s up to date on the latest unfounded theories. Sara, meanwhile, only trusts official fact-based data that’s been reported through official channels. The two debate each other on what’s real and what isn’t.

Note how, dramatically, this is a much more interesting way to talk about the pandemic than a simple Q & A session. The main difference is that there’s conflict between the characters and whenever you have conflict, the scene is more charged, and when a scene is more charged, it’s generally better.

This isn’t the only way to write good dialogue, of course. But it’s an example of where your mindset should be to set a stage for the most interesting conversations. You want to create a situation that has some dramatic value and isn’t just characters saying what you need them to say to set up the plot.

But don’t get too wrapped up in that. You don’t need to focus on dialogue in the first draft. You need to write the darn script. So whatever you do, keep writing. And stop sabotaging yourself. You have the time. And as long as you don’t judge your writing, you will get your 8 pages. Trust me. You just have to sit down and do it.

You can find Day 1 of Prep here and Day 2 of Prep here.

When Stephen McFeely and Christopher Markus sat down to write the gigantic two-part Avengers finale, they admitted they were overwhelmed by the task. Filling up a six hour screenplay is a daunting experience. So how did they overcome the fear?

They started writing down CHECKPOINTS – major moments in the script.

For example, the scene where Captain America fights himself. They figured out, “Okay, we’re going to have that happen around page X in the story.” Once they were able to lay these checkpoints down on a timeline, they no longer had to write from page 1 to page 300. They only had to write to Page 25, when Tony Stark, Dr. Strange, and Spider-Man fight Thanos’s goons in New York City. And then to page 40, when the Guardians of the Galaxy rescue Thor.

Checkpoints give you smaller chunks of screenplay to conquer. The more of them you have, the smaller those gaps of blank pages become. All of a sudden the screenplay you’re writing doesn’t seem so big and scary anymore.

That’s tomorrow’s goal. I want you to come up with five checkpoints in your script. And then Friday’s goal is going to be to come up with five more, for a total of ten. I’m going to make it easy for you by providing you with the four most common checkpoints.

The first is the inciting incident, which tends to happen somewhere between page 5-12. Depending on your script, it could come sooner or later. All the inciting incident is is the introduction of the major problem your hero faces in the movie. So if it’s Avengers, it’s that Thanos is trying to get the Infinity Stones so he can snap away half the universe. If it’s John Wick, it’s when they kill his dog. If it’s Ad Astra, it’s when Brad Pitt is told his dad is still alive and missing and they need Mr. Pitt to find him.

Not all inciting incidents fall perfectly into the “major problem” category. For example, Uncut Gems. I’m not entirely sure what the inciting incident there is. Maybe it’s when Kevin Garnett won’t give him back the gem right away? Or is it when Sandler initially receives the gem? Not sure. Parasite as well. No real problem enters our poor family’s existence in the first act because the infiltration of the rich family’s home was the poor family’s idea to begin with. I suppose you could say that the inciting incident is when the family friend comes to the son of the poor family and tells him about the tutoring job.

In these cases, think of the inciting incident as any plot moment that jumpstarts the story. So Adam Sandler receiving the gem in the mail jumpstarts Uncut Gems. The son being alerted to the tutoring job jumpstarts Parasite.

The second checkpoint is the end of the first act, which is when your character commits to the journey. After the inciting incident, there is often a “refusal of the call” or a “delay in action.” But, eventually, our hero decides to go on the journey because there wouldn’t be a movie if he didn’t. This occurs around page 25-27 in a 100-110 page screenplay.

You see this in just about every Pixar and Disney movie. Most recently, Onward. Ian and Barley head off in search of their father. Inception when they head into Robert Fischer’s mind. Every Mission Impossible movie when they actually go off on the mission. This is where your movie officially begins.

Of course, just like the inciting incident, this doesn’t fit perfectly into every movie, particularly ones where the hero doesn’t go on a journey. Sometimes your hero is stuck in a house, like Michelle in Cloverfield Lane. If your script is non-traditional, look for something that approximates a first act turn. In Cloverfield Lane, for example, I might classify the first act turn as the moment Michelle DECIDES she’s going to try and get out of here. That switch in her demeanor from reactive to active signifies a new energy in the story.

Next we have the midpoint shift. Or the midpoint escalation. The best midpoint shifts transform the story. Make it feel different from the first half of the movie. You do this so your movie doesn’t have the same energy and feel the entire way through. Remember that predictability eventually equals boredom. So you want to use your midpoint shift to change things up a bit. A good example would be the midpoint shift of The Invisible Man. That happens when Cecilia gets booted out of her friend’s house and decides to prove this man is after her instead of allowing him to do what he was doing through the first half of the movie, which was torture her.

Or Parasite. That film had one of the most daring midpoint shifts I’ve ever seen, when they introduce a secret basement floor where a third family is hiding.

Finally we have the LOWEST POINT, which will take place at the end of your second act (between the pages of 78 and 90). Lowest Points are easy to come up with because it’s always some connection to death. Either literally or symbolically. It could be our hero’s friend died. If the main hero is a chef, maybe his restaurant closes down for good (dies). To use Invisible Man again, Cecilia is in a nut house, she’s tired of fighting, so she slits her wrists. In Parasite, it’s when the poor family’s house is flooded, destroying everything (their house literally dies).

So there you have it. Four checkpoints to get you started.

How do you come up with six more? That’s up to you. It could be one of the first scenes you imagined when you came up with your idea. Like the hilarious scene when all the human characters meet the game versions of each other in Jumanji. Or the convenience store scene in The Hunt. It could be something visual, like the famous giant piano playing scene in Big.

It may be a plot twist that happens, like the reveal of the girl in JoJo Rabbit. Or the surprise death of one of your characters. It could be a major monologue from one of the characters (Jules’ Big Kahuna burger monologue scene in Pulp Fiction) or a killer dialogue scene (DeNiro and Pacino in Heat) showdown. If you can envision it, it can be a checkpoint.

Some final thoughts. It’s important that you do this because we’re going to be making a mini-outline over the weekend and the more of these you have, the easier it will be to construct your outline.

Also, if you can, try and balance your checkpoints out so that you have roughly the same amount in the second half as you have the first. It’s easier to come up with first-half checkpoints because that part of the story is clearer in your head at the moment. But one of the big challenges of finishing a screenplay is that back half of the second act. It’s the section of the script we know the least about before we write. So if you can throw a couple of solid checkpoints in there, you’re going to be ahead of the game.

Now get to it!

It’s going to be Monday Madness when I review Hobbs & Shaw and determine the question that’s been eating at us for over a decade. Is it possible to make a good Fast and Furious movie without Vin Diesel? They’ve tried before and the results were disappointing. Could the rumor be true? That Dominic saying “family” once every five minutes is the only way these movies work? I’m eager to find out. I’m also eager to see what happens when you make a Fast and Furious movie a sci-fi flick, since apparently that’s where the franchise is headed.

Good news this week as participation does not require any dancing.

If you haven’t played Amateur Showdown before, it’s a cut throat single weekend screenplay tournament where the scripts have been vetted from a pile of hundreds to be featured here, for your entertainment. It’s up to you to read as much of each script as you can, then vote for your favorite in the comments section. Whoever receives the most votes by Sunday 11:59pm Pacific Time gets a review next Friday. If you’d like to submit your own script to compete in a future Amateur Showdown, send a PDF of your script to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the title, genre, logline, and why you think your script should get a shot.

Note: Accessing scripts should be a lot easier this week as I’m using Google Drive. :)

To all who have entered this weekend’s contest, I wish you…. GOOD LUCK!

Title: Cop Cam

Genre: Found footage/Crime-thriller

Logline: Told through the lens of a police-worn body camera, a retiring cop with a baby on the way faces the most harrowing shift of his career after a traffic stop devolves into a violent mess affecting both sides of the law.

Why You Should Read: I’ve always thought a found-footage film involving a cop’s body camera would be an interesting concept to explore. Police-worn body camera footage persists as some of the most controversial, yet fascinating forms of real-time-media in existence today. Think about it, when’s the last time you didn’t click on a “contains graphic content” police video that was shared to social media? The footage always tells a story, but rarely captures the facts in their entirety. As a police lieutenant, I watch countless hours of body cam footage from the officers under my watch and am rarely ever bored. On the contrary, they typically inspire movie ideas for my scripts. For “Cop Cam”, I wanted to infuse elements from some of the most disturbing videos I’ve encountered into a grounded, found-footage crime-thriller told from the first-person perspective of one cop’s final day on duty. While most found footage films deal in supernatural horror, I aimed to bend the genre here into purely thriller territory, although a lot of feedback has mentioned it certainly flirts with horror. The script just received positive coverage from WeScreenplay: “This high-octane, action-packed thrill ride is a rip-roaring page-turner told with unflinching authenticity. The amount of story, twists, and turns in this tight script is a strong showing of narrative economy. A cops and robbers caper that unfolds like a beautiful car wreck with a continually worsening state of affairs that’s likely to appeal to mass audiences. This is one flat out cool movie.”

Title: Coven

Genre: Psychological Horror

Logline: When a homeless teenage girl becomes the newest member of an acid-popping doomsday cult known as The Coven, a long-dispirited member makes it her mission to escape with the young girl before she falls under the spell of The Professor, their abusive yet charismatic leader.

Why You Should Read: Like many screenwriting hopefuls, I submitted some scripts to the Nicholls this year, hoping that one of them may be the script that changes everything. Unfortunately, this year was not my year. Nevertheless, “Coven” finished in the top 10% – a personal best and a sign that my work is improving year after year. While I impatiently wait for the reader comments, I figured it would be awesome to get some feedback from the community that arguably taught me the most about the art of screenwriting.

“Coven” is my stab at one of my favorite horror sub-genres: the cult film. It’s a weird, violent, psychedelic, slow-burn story with a heavy emotional core, featuring a strong female lead who works to escape the trauma of her past and the physical (and psychological) prison she’s found herself in. And to sweeten the pot, about 90% of the film takes place in one location, so it can made on a shoe-string budget (I’m looking at you, Blumhouse!).

Many thanks to anyone who gives this a read; whether it’s the whole thing or just a few pages, any and all feedback is greatly appreciated! And a special thanks to Carson for holding a forum where a nobody like me can get their work in front of so many smart and talented people. Looking forward to hearing what you guys and gals have to say!

Title: MYSTERY MAN

Genre: Action Comedy

Logline: America’s favorite mystery author returns home for his father’s funeral and reluctantly teams up with his crazy sister who believes their father was murdered.

Why You Should Read: The inspiration for “Mystery Man” was derived from a love for whodunnits and my wacky home state of Florida. With twists and turns that will keep you guessing to the very end, “Mystery Man” is raunchy at times, heartfelt at others, and always weird. “Mystery Man” was a semifinalist in both the 2017 Stage 32 Annual Comedy Contest and Screencraft’s Annual Comedy Contest. It also placed second in Final Draft’s Annual Big Break Contest (2017) in the comedy category. Subsequently, “Mystery Man” was optioned for a year. The option recently expired so it’s now back on the market!

Title: INK

Genre: Noir

Logline: When screenwriter Don Miller goes missing from the lot of Dionysus Pictures, toon actor Chester Charles is sent to try and discover where he is, but soon finds himself shoulder deep in the greatest conspiracy that Tinseltown has to offer.

Why You Should Read: My last script WONDERLAND was featured here on Scriptshadow and I received some really great feedback from the community. One of the big notes was that people wanted to see me play in my own sandbox rather than build on someone else’s work… So, I created one… A conspiracy thriller set in an alternative 1950’s Hollywood where the moguls that run the place are willing to turn to nefarious means to keep their stars in order (both human and toon), their wallets fat and the ‘Red Menace’ at bay. INK marries the Disney Conspiracies with Who Framed Roger Rabbit and adds a smattering of observations about the manipulative power of the media.

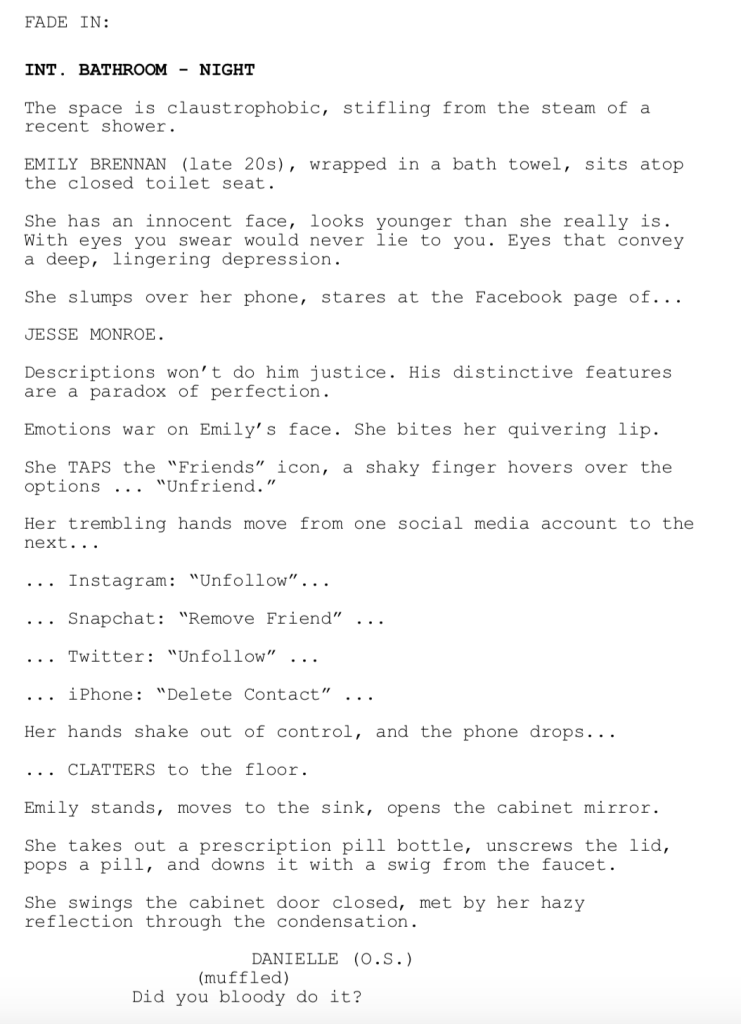

Title: BROKENHEARTED

Genre: anti-rom-com

Logline: In a misguided attempt to mend her broken heart, a lovelorn twentysomething decides to pursue a casual, no-emotions-attached fling with a womanizing stranger from Tinder.

Why You Should Read: Greetings! An older draft of this script won the Austin Film Festival Drama Screenplay Competition in 2017. Prior to the festival win, I secured a manager who found me on Blcklst after Brokenhearted received that magic number 8 (amongst some 7s and 5s.) The script got me general meetings at a few reputable production companies and one big studio (Naming names feels tacky.) I had the opportunity to pitch on an open assignment. (Crashed and burned obviously.) Brokenhearted has always been a divisive script, and with the encouragement of my manager, I did a massive rewrite of the script alongside a credited director. The rewrite involved structural changes, supporting character gender swaps, and massive “killing of darlings,” particularly chatty banter dialogue sequences. The new (and improved?) draft landed just outside the Top 5% (Quarterfinals) of the Nicholl Fellowship. I received the dreaded “some good news: your script just missed advancing, placing among the next 100 scripts after the 365 quarterfinalists” email. Aside from reads from the director, my manager, and a few writer friends, I haven’t really put this script out there for public scrutiny. Nicholl 2019 was the first real litmus test. I’ve written, re-written, read, and re-read this thing so many times that I’m completely emotionally detached. The re-write was a rewarding experience, one I feel produced a stronger draft. But my eyes stayed dry. I can’t help but wonder: has the script lost its soul? I’ll admit to being a bit of a lurker here on ScriptShadow for about the last year. As someone who has been active in the screenwriting community and contest circuit since 2014, I don’t know why it took me so long to join the party. (That’s a lie. It’s because I’m an INFJ.) And that was a long-ass “why you should read.” I promise the screenplay has a ton of white space. Thank you for your consideration!