Search Results for: day shift

Read Scriptshadow on Sundays for book reviews by contributors Michael Stark and Matt Bird. We won’t be able to get one up every Sunday, but hopefully most Sundays. Here’s Matt Bird with the graphic novel DMZ!

It started with Neil Gaiman’s Sandman. Sandman established a certain model for adult-aimed comics epics (especially those published by DC Comics): The creators put out a monthly series, broken up in to 5-7 issues storylines, which get collected into trade paperbacks along the way, and the whole thing builds to a big conclusion around issue 70, meaning that you end up with ten graphic novels on your shelf, comprising the whole saga. And then Hollywood starts trying to adapt it, though they can never decide whether to make it into an HBO miniseries or a movie. And then they enter development hell, never to emerge again.

It started with Neil Gaiman’s Sandman. Sandman established a certain model for adult-aimed comics epics (especially those published by DC Comics): The creators put out a monthly series, broken up in to 5-7 issues storylines, which get collected into trade paperbacks along the way, and the whole thing builds to a big conclusion around issue 70, meaning that you end up with ten graphic novels on your shelf, comprising the whole saga. And then Hollywood starts trying to adapt it, though they can never decide whether to make it into an HBO miniseries or a movie. And then they enter development hell, never to emerge again.

It happened with Sandman, then James Robinson’s Starman, then Garth Ennis’s Preacher, then Brian K. Vaughn’s Y, The Last Man, and so on and so on. The one example that actually seems to be crossing the finish line is a similarly epic series that wasn’t made by DC (coincidence?), Robert Kirkman’s The Walking Dead, which Frank Darabont has set up as a series at AMC. Will this finally provide a repeatable model for how to port a creator-owned comics epic over to another medium?

Most of the above books were published by DC’s creator-owned imprint Vertigo. My favorite ongoing Vertigo book is one that I’ve never heard any rumbling at all about adapting: Brian Wood’s DMZ. Neither the book nor the creator get any mention at IMDB Pro. I did find this quote, from a recent interview with Wired Magazine: “I don’t write comics to see them turned into films since the odds of yours being one of the very, very few that get turned into movies is so small you might as well just play Lotto. But there’s always something going on: options, meetings and treatments being written for some of my books. I’ve learned with bitter tears not to feel like it’s something that’s supposed to happen. I think of it as free money.” So it sounds like he’s up for it if he someone can make it work. So what are you waiting for?

The monthlies started coming out in November 2005. Issue 51 comes out this month. The ninth book collection, Hearts and Minds, comes out next month.

Carson has pointed out that there are a dozen variations floating out there of the ultimate “war comes to a big American city” story, and one of them has to get made eventually. I’m convinced that Americans of all political stripes are secretly wracked with guilt about our predilection for turning cities all over the world into war zones. We get angry when the occupied become insurgents, but we also can’t help but wonder: “what would I do if the war came to my town?” That big, fat question needs to be vented onscreen. Various attempts to answer it have come in the form of spec scripts about alien takeovers or invasions by foreign governments. Wood goes for option number three: civil war.

Ironically, when the series started I thought that the set-up was too dated: a militia that starts in Montana quickly wins over all of Middle America, causing the federal government to concentrate in the northeast. When full-scale war breaks out, Manhattan is caught in the middle and becomes the official De-Militarized Zone. When the series started in 2005, America’s actual militia-types had fallen back in love with the federal government and this seemed to me like a very ‘90s idea. Now the militias have come roaring back to life and it all seems downright prescient. Wood mixes up the politics by making the militia into anti-military libertarians and the federal government into pro-corporate sleazebags. Niether side is sympathetic. Instead, our sympathies are with the victims of the war: the hard-scrabble skells left behind on Manhattan, who are dedicated to rebuilding their city every time power shifts and new bombs fall.

The series begins as a New England journalism school graduate named Matty Roth gets the internship assignment of a lifetime: accompany the country’s most famous war reporter on a daytrip into the DMZ. Of course, as soon as they arrive, thing go horribly wrong. Soon, only the intern is left, and he’s horrified to see the under-reported suffering of the civilian population. He cuts a deal with the Fox-News-type organization that sent him in: I’m all you’ve got left, so I’ll be your eyes and ears on the ground from now on if you agree to let me report the truth. Over the course of the fifty issues, he’s had to re-negotiate his power-position many times, as his relationship to the local insurgencies and the two governments keeps shifting, but that’s still the basic set-up.

It’s hard to write about journalists without messing it up. You have the same problems that you have with cop or lawyer movies, but greatly magnified: We all know that a protagonist should be good at their job. We also know that, at some point, as the stakes raise, it has to all become personal. (I talked about this tendency on my blog here and here) But there’s a big problem: for cops, for lawyers, and especially for journalists, this is an inherent contradiction. If you lose your objectivity, you become bad at your job. Journalist movies always build up to that moment where the hero says “Damn your ethics! I’m going to take a side!” That’s terrible journalism.

But DMZ is an ongoing series, and though Matty faces several moral dilemmas and crosses the occasional line, Wood does an amazing job of letting the drama come from Matty’s overall dedication to objectivity. Even when he becomes committed to saving the city, he knows that all of his power derives from his credibility, and that credibility comes from not drinking anybody’s kool-aid. This is a huge real world concern that has been little-dramatized. It’s why DMZ works so well as a comic and it should be the heart of any attempt to turn it into a movie or TV series.

Matt Bird bloviates about movies (and occasionally comics) everyday over at Cockeyed Caravan.

Genre: Horror/Action

Premise: A lonely bounty hunter trying to improve his life goes around LA killing secret monsters hiding inside human bodies. His job gets a lot more complicated when he’s forced to team up with his first partner.

About: This one sold for a bunch of money in a competitive bidding war that ultimately went to Netflix. David F. Sandberg is directing.

Writers: Gregory Weidman and Geoff Tock

Details: 92 pages

I’ll be honest.

All I care about right now is aliens. I’ve been following this story about the U.S. having possession of crashed alien ships for the last 24 hours. If it was up to me, I would spend the next ten Scriptshadow posts talking about it. I actually looked for an alien ship outside my place this morning. So far, one hasn’t stopped by.

But I understand not everybody here is as enlightened as I am and that you don’t care that the aliens are coming (or have they always been here??). So I’m going to restrain myself from turning this into UFO Shadow. FOR NOW.

The cool thing is that we have a script worthy of its own headlines today. “Below” resulted in a serious bidding war and sale. It’s going to be directed by David F. Sandberg. I’ve met Sandberg two times now, once on the set of Lights Out and another time randomly in the aisle of a supermarket. He’s an excessively sweet guy. He just emanates positive energy and we don’t have enough of that in this town.

So I’m really rooting for this script.

“Our Man” is our hero. He lives alone in LA in a tiny apartment, listens to self-help podcasts all day long that preach things like, “You can’t depend on anyone. Only you can move up in the world by your own actions.”

Which is exactly what Our Man is trying to do. He’s a bounty hunter of sorts. He gets text messages every week for a new job. “5% above normal rate” they say, then gives him a location. Off he goes and kills these monsters, tentacled creatures hiding inside human bodies called “dregs.” Afterwards, he takes the dreg skull to a buyer who pays him cash.

Our Man’s dream is to open his own karaoke bar. And he only needs a few more jobs to start that dream. But when he gets a text for his next job, it’s accompanied by, “Now you have a partner.” Our Man tries to ignore it, but after doing the job, his new parter, a woman slightly older than him named “Boxer,” shows up.

Boxer attempts to befriend Our Man, who does everything within his power to stay alone. He doesn’t do the whole “connect with people” thing. But she keeps chipping away at him and soon they’re drinking beers and eating food truck tacos together. To his surprise, Our Man likes Boxer.

As they go over the uptick in jobs lately, Boxer theorizes that something big is about to happen. And when they catch a dreg kidnapping a person instead of killing him, like they usually do, she knows something is up. That’s when they get a shocking text. Their next job is 700%(!!!) above normal rate. Could it be the Queen Bee? Our Man doesn’t want to find out. But they don’t have a choice. And off they go.

There are a couple of big things that come to mind when you read “Below.” The first is that this is the third version of this story that’s been on Netflix. People hunting down supernatural creatures in Los Angeles. You had Bright. You had Day Shift. And now you have Below.

That surprises me. But maybe there’s an executive at Netflix who just loves these types of movies. I get it. If I was an exec, every other movie I greenlit would have aliens. But it did catch my eye because you’re always looking for something fresh. So I was surprised that this was so similar to other stuff on the streamer.

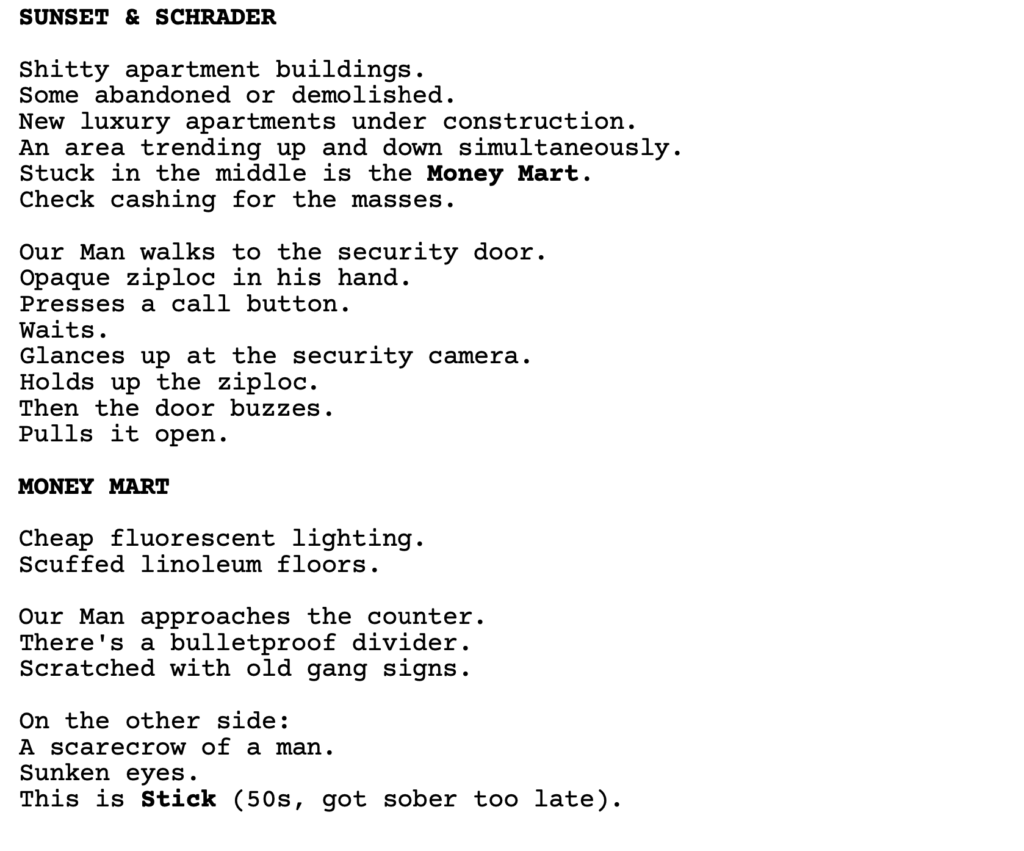

The other big thing going on in this script is the Walter Hill writing style. That’s where you write sentences vertically instead of one after the other. It’s tough to endure if you read a lot of scripts because you’re used to getting that line in between every paragraph. And here, you don’t get that breather. So I’m not a fan of it. But I suppose if you don’t read a lot of scripts, it doesn’t disrupt your reading pattern much.

As for the story, I was on the fence for a while.

As for the story, I was on the fence for a while.

I should bring this up because I JUST TALKED ABOUT IT in the newsletter and here it is, being done in all its glory, not once but TWICE WITHIN FIVE MINUTES. I mean, I was shocked.

25 pages in, Our Man gets stopped by a cop. The cop is seconds away from discovering that our man just killed a “human.” And then a kid drives by and throws a bag of urine at the cop, so the cop jumps in his car to chase him. This is the worst thing you can do as a writer – SAVE YOUR HERO FOR HIM. A hero must save himself. That’s when we fall in love with heroes!

Go watch when the T-1000 shows up to take on the Terminator in T2. You get a 20 minute series of attacks. Not once does James Cameron save the Terminator. The Terminator has to earn every single victory over the T-1000.

So then, less than 2 seconds later, Our Man is walking back to his car and gets surprise-jumped by a dreg. They battle. The dreg has the upper hand. It’s easily about to kill Our Man. And then, what do you know, BLUE LIGHTNING appears from the side. It kills the Dreg. It’s Our Man’s new partner, who came in to save the day!

That is twice – TWICE – that the writer saved the hero.

You’re probably asking, well, wait a minute Carson. If this is so bad, why is the script selling for so much money?

I’ll tell you why. Because it’s better than both Bright and Day Shift.

Something happens to this script when Boxer arrives. Because, before Boxer, this was a cold sad depressing world. She then comes in with this enthusiasm that not only gives Our Man hope – it gives US hope! I loved that she was older, which is a different kind of dynamic than we’re used to with these pairings. I loved that all she wanted to do was be friends with Boxer. And she wouldn’t let him off the friend hook.

And of course, once she wins that battle, we’re a HUGE FAN of them. We now want them to succeed together. What this does is that when they get into trouble, we feel a lot more fear due to our strengthened emotional attachment to the team. This is what screenwriting is all about – it’s mining real emotion from fictional characters. It’s the hardest thing to do in the world and it’s always a minor miracle when it happens. These writers make it happen with that relationship.

Plus you have this mystery with these monsters. What are they? Who’s in charge of them? What do they want? Why are they being asked to kill them? With the vampires in Day Shift, it was all straight forward. With Bright, you had some dumb super-fairy that we didn’t care about. The things in this script genuinely have you curious what the bigger mystery is and that keeps you turning the pages.

I even got used to the annoying writing style after a while. Very curious to see what David Sandberg does with this. I hope the directing style feels different from Bright and Day Shift.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Early on in the screenplay is when you make the impression on the audience of your main character’s defining trait – the thing that’s holding him back in the world. If you don’t make that impression loud and clear, the reader isn’t going to ever know your hero. The mistake a lot of writers make is to be too subtle about this defining trait in the fear of being too “on the nose.” I can’t tell you how many times I’ve given this note and the writer has said, “Yeah but I didn’t want to be on the nose.” When it comes to who your main character is, you want to be clear. And Weidman and Tock take five separate moments in the opening 15 pages to highlight that our hero is ALONE. He’s LONELY. He’s BY HIMSELF. It ingrains in the reader’s head that this it the thing that our hero needs to overcome in this story.

What I learned 2: Give your hero a life goal that’s a little surprising and a little against type. It adds more depth to the character. One of the best creative choices in the script was that this downbeat loner loved karaoke. So much so that his dream was to open a karaoke bar! Something about that choice made Our Man feel real. You could’ve easily done the cliche thing of having his goal be to retire to a small house on a beach in Mexico. But by adding this more unexpected choice, he stands out from all the cliched characters before him.

Genre: Horror/Sci-Fi

Premise: Trapped on a remote North Dakota farm in the middle of a bone-chilling winter storm, a deaf 12-year old girl must try to survive her murderous foster parents, who’ve been influenced to kill by a mysterious radio signal from deep space.

Why You Should Read: Deep came about from my desire to write a story putting the most vulnerable type of person in the most terrifying situation I could imagine. A very early draft of Deep made this year’s Page Quarterfinals. After feedback, it’s since gone through a strenuous rewrite. At 87 pages, and tightly structured, it’s a lean, electrifying read. Looking forward to any critiques from the Scriptshadow Community.

Writer: Dean Brooks

Details: 86 pages

I’m still looking for a good professional horror script to review in the Halloween Newsletter. You guys don’t want me stressed out looking for a script until the last second or I’m going to eat all five bags of Halloween candy that are in front of me. This candy is for the kids! Yet you would have them starve?! You would have them knock on my door only for me to say, I’m sorry, but I don’t have any? Go blame the Scriptshadow readers for not sending me a horror screenplay. Off the top of my head I’m looking for M3GAN and the Jamie Foxx vampire script Slamdance Contest winner, Day Shift. Or if there’s anything else, e-mail it to carsonreeves1@gmail.com.

On to last week’s WINNER! Congrats to Dean Brooks. He not only won Horror Shodown, beating out a couple hundred submissions, but he survived a glitch whereby it was difficult to download his script! I heard some people were never able to download it. So good job to Dean. Now let’s see if his script is all that.

Makayla Brenna is 12 years old and deaf. But her lack of hearing is the least of her problems. Her parents are hardcore meth addicts and extremely abusive. In the opening scene, Makayla sees a cop car outside who’s stopped someone for speeding. Feeling like this might be her only chance to escape her parents, she makes a run for it, just barely evading her shotgun-wielding father.

A few months later, she’s introduced into a new home with foster parents Joe and Adele. Of the two, Adele is more skeptical that they can pull this off. Whereas Joe is excited to finally have a kid to raise. He’s so excited that on their first full day together, he introduces Makayla to his backyard amateur observatory shack where he can watch and listen to the stars. Makayla thinks it’s pretty cool and likes Joe immediately.

The next day, Makayla is enrolled in school and makes a couple of friends right away. However, that night, Joe goes into the observatory and never comes out. The next morning, he’s acting distant and weird. He then has a seizure. Adele takes Joe to the hospital and drops Makayla off at school.

Joe comes home happy and healthy but after going into the observatory again, he comes back acting weird. That night, Makayla hears Joe violently going after Adele in the other room then taking her outside, presumably to the observatory. Sure enough, the next morning, Adele is acting weird and distant as well. It appears that some evil alien entity has found its way into their consciousness and is now controlling them.

Makayla isn’t quite sure what to do. At school the next day, she decides to make a run for it. But Adele, doing her best Robert Patrick impression from Terminator 2, tracks her down, kills the person who helped her escape, and brings her back to the house. It is here where both Joe and Adele will attempt to “make her listen” to the space sounds in the observatory. But Makayla can’t listen. She’s deaf. So what lengths will the parents go to to overcome this problem?

I went on a complicated journey with this one. At times I loved it. At times I doubted it. I’m still not sure where I land on it but it’s definitely worthy of being reviewed so I think you guys made the right choice.

The first scene is a cut above. And that’s saying a lot since I’ve read a TON of first scene Contest entries lately. I think a couple of factors helped it out. Opening scenes with characters in danger is par for the course with horror screenplays. But what “Deep” does is it sets up an EMOTIONAL dilemma as opposed to just a VISCERAL dilemma. This isn’t some random girl being held by a random psycho. This is two parents who have imprisoned their daughter. So, right away, there’s an extra emotional kick to the scene.

Next, the heroine is deaf. Deafness can be cliche but here it was believable. And it made it so the evil parents weren’t just imprisoning a regular girl. Their daughter is disabled. So there’s some extra nasty added to these villains that made us want Makayla to escape even more.

I thought the integration into the new home was also well done. Whenever I’m reading a script, I’m looking for authenticity and specificity. If everything is too familiar, I get bored. I need those differences that make the story unique. So the wife being Native American, for example. It was a nice detail that told me the writer had put more effort into this than the average person.

But then we reach the observatory stuff and that didn’t sit well with me. For starters, it felt like a different movie. We’re going from a deaf foster child escaping abusive meth-head parents to a guy with his own space observatory? Who then, the DAY AFTER THEY ADOPT OUR HEROINE, gets infected with an alien virus?? What are the odds of that happening?

I get that it’s a movie and, to a certain extent, what happens in the first act is excused from being a coincidence. But you shouldn’t try to cram more than one huge event into your first act. And I felt that this deaf girl escaping her terrifying abusive parents was the hook. Getting introduced into a new family was the hook. To then add this secondary hook – I’m not going to lie – it took me out of the script for the next 30 pages.

Then I started to see what Dean was doing. With the mom and dad becoming possessed by the alien entity, Makayla is essentially right back in the same situation. The problem is, when you do that, you want to construct a scenario by which, with the previous situation, there was a choice to succeed and the hero took the easy way out. That way she can learn and when presented with the same choice again, this time she makes the heroic decision.

This is what The Invisible Man did. She always cowered to her abusive husband. But, then, later in the movie, she chooses to stand up to and kill her husband. In this script, because the main character is so young, you can’t really do that. And, to be honest, Makayla already was a hero by escaping her parents in that opening scene. So there wasn’t anything else to do with her character except repeat what you did in that opening. If a character is repeating stuff they’ve already done, they’re not evolving. They’re not arcing.

But then you’d get these great scenes like when Makayla was at school and her mom is now possessed and she’s picking Makayla up afterwards and Makayla knows if she goes with her, she’s dead meat. So she tries to run away after school and her mom chases her down. It’s a really intense well-done scene.

I just don’t know if this weird deep-space alien virus possession thing can work. It never felt organic to the story. It’s almost as if Dean had two scripts. One about an abused deaf girl and another about an alien virus and then randomly decided one day to combine them into a single script. Cause that’s how much these two concepts were fighting each other.

Early on in the script, when Makayla first sleeps in her new room, there’s a moment where she thinks she sees the spirits of her parents in the corner. I wonder if there’s a version of this where her birth parents die in a police shootout after Makayla is rescued and then their spirits follow her to her new home, and their goal is to try and take over the bodies of her new parents. Makayla tries to tell her new parents this is happening but they, of course, think she’s just traumatized. I’m not sure if that has the same sex-appeal as this concept or if Dean would even want to write a story like that. But the biggest reason this did not get a ‘worth the read’ from me is that I could never marry these two worlds – the alien possession and the abused deaf child. They never felt like the same movie to me.

Script Link: Deep

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m all for moving the story along quickly. But you have to be cognizant of the situation and construct your timeline accordingly. One of the problems with this script is that Dean tried to cram the entire story too closely together, with no time passing in between major plot beats at all. Makayla shows up on Day 1. And on Day 2, she’s already enrolled in school and her new father is possessed by an alien! lol. These plot beats need time to breathe. It’s okay to throw a montage in there of the first week where Makayla is getting used to her new parents and home. It’s okay, after she’s enrolled in school, if we give a montage of her getting used to that environment as well. As much as screenwriting is about moving the story forward quickly, it still needs to feel natural. And if you’re cramming major plot beats too close together, it will feel anything but natural.

Week 14 of the “2 Scripts in 2024” Challenge

Week 1 – Concept

Week 2 – Solidifying Your Concept

Week 3 – Building Your Characters

Week 4 – Outlining

Week 5 – The First 10 Pages

Week 6 – Inciting Incident

Week 7 – Turn Into 2nd Act

Week 8 – Fun and Games

Week 9 – Using Sequences to Tackle Your Second Act

Week 10 – The Midpoint

Week 11 – Chill Out or Ramp Up

Week 12 – Lead Up To the “Scene of Death”

Week 13 – Moment of Death

Okay, so, just to remind you, this entire surgical procedure we’re calling “writing a screenplay,” is approaching the endpoint. We’ve opted for the 110-page version. Which means that, after this week, we only have 10 pages left.

Where that leaves us is in the sweet spot of the climax.

It took me a long time to figure out how to approach the climax of a screenplay. Then, one day, it became as clear as the springs from which Evian gets its water.

A climax IS ITS OWN SCREENPLAY.

For that reason, it has its own beginning, middle, and end.

For those of you who don’t know what each of these sections stands for, let me remind you:

Beginning – Setup

Middle – Conflict

End – Resolution

For anyone who’s intimidated by this information, think of it this way. Almost every story you’ve ever told anyone – even if it was just a story to your husband about what happened to you at work – chances are you SET IT UP for them (“My boss called me into his office”), you then explained THE CONFLICT (“He said that Karen had accused me of stealing her work and taking credit for it”), before finally giving them the RESOLUTION (“I told him that Karen was a lying psycho who’s been trying to make me look bad to everyone. He apologized and said he’d have a long talk with her.”).

It’s the easiest way to tell a story. So it makes sense that we’re depending on this formula for our climax as well.

Therefore, almost everything you used to map out your 110 page screenplay, you’re going to use to map out your climax.

The first thing you have to do is figure out how long your climax is going to be. Since your third act in a 110 page screenplay is around 27 pages, the climax has to be less than that.

Because, before you get to the climax, you have three main beats that you’re trying to hit.

First beat: “Stop Crying and Get Up Off Your Keister”

Remember, at the end of the second act, your hero had fallen to his lowest point. Some level of death, either literal or metaphorical, had occurred. So, it wouldn’t make sense to jump from that to a big flashy climax.

You need a beat where they pick themselves up, dust themselves off, and shift their internal momentum from “defeated” to “I’m going to give this one more shot.”

Second beat: “I Love It When A Plan Comes Together”

After they’ve defeated their whiney b**ching and are ready to fight again, they need to come up with an actual plan. You don’t roll up on the Death Star hoping to figure it out on the way. You need that moment where everyone sits down and they explain how to destroy the Death Star.

Third beat: “The Calm Before The Storm”

Most good stories give the audience one final beat before the climax that works as the “calm before the storm.” For example, in Avatar, before the Na’Vi go off and fight the humans, they convene at the big tree of life. They have a little pow-wow where they mentally prepare for what’s about to come and then off they go.

How long should these scenes be? Pretty short, but it will all depend on the movie and the story you’re telling. But I would say 2 pages tops each. So 6 pages in total.

Cause the way you gotta look at it is, you need a few beats after the climax as well, which is going to add pages to your third act. Maybe we have 6 pages AFTER the climax is over.

So let’s do our math = 27 pages – 6 pages (lead up to climax) – 6 pages (post climax).

That leaves us with about 15 pages for our climax. Which is optimal in my opinion. 15 pages gives us an adequate amount of time for a great climactic sequence.

I know some of you hate math but we gotta use it in order to understand how to set up our climax. Remember, like I said, the climax is its own miniature movie. It has a setup, a conflict, and a resolution. Since we now know our climax is 15 pages, we can divide that in the same way we divided our script = 25% for the setup, 50% for the conflict, and 25% for the resolution.

While this is a good guide, I’ve found that setups and resolutions in climaxes tend to be shorter, percentage-wise, than their full-script counterparts. So instead of being 25% in setup, it might be 15%. Instead of 25% for the resolution, it might be 10%.

That’s because the climax is really about the showdown between the protagonist and the antagonist. So that middle section of your climax — the CONFLICT – is the meat.

With that in mind, here’s what we get…

Climax Setup – 3 pages

Climax Conflict – 10 pages

Climax Resolution – 2 pages

I’m already hearing some of you groan. Carson! You can’t possibly distill art down into such a mathematical formula. You’re right. I’m not saying you have to follow this to a T. What I’m saying is, this is the way it’s done in most movies. Therefore, you should use it as a template. How much you want to stretch or condense or twist the template is up to you. But there’s one constant here I can promise you that you need: Which is that your climax needs form. It needs shape. And this is the best way to shape it.

In all the internet hype about an upcoming Happy Gilmore sequel, I watched the original movie recently and the climax follows this formula very closely. The final tournament day between Happy and Shooter is roughly 17 minutes, so a couple of minutes extra.

And that’s why I say these page-counts do have some flexibility to them. I mean, Titanic has a 45 minute climax. The film itself is also twice as long as a regular movie but, the point is, each movie will have its own needs.

The only other thing I want to highlight is that, within your climax, it needs to look like your hero LOST. Just like at the end of your second act, your hero had a “lowest point,” the same thing is going to happen at the end of your climax’s second act.

For example, in Happy Gilmore, as he lines up his final putt, which he needs to win the tournament, one of Shooter’s minions forces a giant TV stand to fall directly in the way of his shot, making an already difficult shot impossible.

In that moment, we think Happy Gilmore is dead. There’s nothing he can do to win this tournament anymore. You need that same moment in your climax.

Okay, we’re almost there, people! We conclude the writing of our first draft next week! Congrats to everyone who’s made it this far! :)

Genre: Horror

Premise: Monsters that roam in daylight keep a small, rural family confined to a nocturnal existence, but when their son starts to question the monsters’ existence, the entire balance of the family is thrown off.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List with 8 votes. Screenwriter Nick Hurwitch is the winner of the Nate Wilson Joie de Vivre Award from the UCLA Professional Program and the Austin Film Festival Pitch Competition.

Writer: Nick Hurwitch

Details: 107 pages

Sometimes I think that coming up with movie ideas is the hardest thing to do in the world. Because there seems to be this balance you have to hit that’s so precise, even if you’re a millimeter off, the idea falls apart faster than a Jenga puzzle on a Roomba.

That balance includes coming up with a concept similar to what we’ve seen before. But also is JUST UNIQUE ENOUGH that it feels fresh. And the crazy thing is that you don’t always know if it’s hit that sweet spot until it’s released into theaters.

No movie encapsulates this better than M3GAN. Extremely familiar concept – Kid buys a spooky toy that’s possessed. Then all they did was turn the “possessed” element of the doll into AI. And the movie did gangbusters.

What throws everything off is that, every once in a while, a movie slips through that doesn’t do anything new, and then somehow does great at the box office. The John Wick script (for the original film) still perplexes me to this day. It’s about as basic a “guy with a gun” idea as you get. Those are the ones that keep me up at night.

Today’s script seems to bear some of this same DNA. Based on the logline, I feel like I’ve seen it before. Let’s hope that I’m wrong.

MAJOR SPOILERS BELOW

At the beginning of our movie, we see a farming family having lunch outside and a monster peering through the nearby cornstalks at them.

Cut to another farming family, who’s waking up just as night falls. The mother of this family is Lynne, a nice kind woman. The father is Gary, an intense type who just wants to get work done. And then there’s 16 year-old Caleb.

The family lives in a post-apocalyptic world where monsters roam the land during the day. Therefore, humans can only come out at night. Which frustrates Caleb to no end. Cause he never gets to experience daytime.

Lynne gets a whiff of Caleb’s growing frustration and starts taking him outside in the mornings, when Gary is asleep. Caleb loves these 10-15 minutes of daylight and his mood shifts. He works harder on the farm. He does better with his studies. He’s happier overall.

But then two things happen. Gary finds out Lynne and Caleb are doing this and is not happy at all. And Caleb becomes more and more interested in what’s out there in the sunlight. Finally, Jeanine sneaks Caleb down to the barn and reveals the truth to him (at the script’s midpoint).

She shows him a meteor that they built the barn over – a meteor that carried Caleb here from the stars. They weren’t saving Caleb from monsters. CALEB IS THE MONSTER. When he’s in sunlight for too long, he grows into a human-tree-like thing with superhuman abilities.

Confused about this new identity, Caleb escapes into the world, where he runs into humans. When those humans try to attack him, he has no option but to fight back. He ends up badly injuring a local man and now that man’s family wants revenge. And they know where the monster came from.

I went from meticulously analyzing the choices in the early part of this script to getting completely lost in it. That’s what a good script is SUPPOSED to do. It’s supposed to make you forget you’re reading a story, whether that’s someone like me, who reads for a living, or someone who reads for enjoyment. The goal is to get the reader to forget they’re reading.

This script did that for 53 pages. That’s when the twist arrived. And it was a good twist! I wasn’t expecting it.

But here’s the problem when you introduce a radical twist at your midpoint. Yes, you create a surge of excitement within your reader. But you also burn the bridge that brought you over into this half of the story. Cause nothing that happened before this twist matters anymore.

You’ve reset your story so you have to come up with a new engine. Now that we know Caleb is the monster, what is this story about? Hurwitch comes close to getting it right. But he makes a big mistake. He goes all in on the “Wacky Aunt” character.

This wacky Aunt/nurse thinks that Caleb was sent here to save the planet — re-plant it or whatever. We’re not interested in that. We’re more interested in the Frankenstein angle of this story. You’ve got this local group of rednecks, one of whom Monster Caleb nearly killed, determined to get revenge.

That alone would’ve been enough to power the second half (them trying to find where this monster lived and then attacking). But if you wanted to, you could’ve grown that group and added 50-100 townspeople and now you’ve got a mob chasing Monster Caleb. That’s all you need. That will give you your second half of the movie.

The Aunt Wackadoodle plot wasn’t script-destroying. But it just wasn’t the right creative choice. Which is one of many hard things about screenwriting. You have to make these crucial creative choices throughout the script and the closer you get to the ending, the more those choices matter. Cause if you don’t make the right ones, we start losing interest during the most critical part of the story. The ending is when you need us obsessively turning the pages, not curiously turning the pages.

I’m Mr. Big Midpiont.

Because what a good midpoint does is it makes the second half of the movie feel different from the first half. That’s exactly what Sundown does. It’s two completely different stories.

However, you can’t come up with a plot-changing midpoint like this unless you have a GREAT plan for the second half of the script. It can’t be one of those scenarios where you shrug your shoulders and say, “I’ll figure it out somehow.” No, you need a plan.

Because the first part of this script was really good. It’s powered by two big story engines. One, the question: Are the parents being truthful with Caleb? And two: Caleb’s conflict. Whenever our hero is stuck in a place they don’t want to be in, it creates this underlying tension that drives the narrative since we know that conflict needs to be resolved.

Once those two story engines are jettisoned by the midpoint, what are you replacing them with? An annoying Aunt who wants to use Caleb’s powers to save the world. I guess that’s technically a story engine because it’s a goal. But we have to care about the character with the goal in order to be interested in the pursuit of that goal.

Then you have this family that wants to kill Caleb. That’s a real story engine but it’s not pushed hard enough. It feels too casual.

But, with all that said, this script still has more good than bad. Hurwitch does a really nice job with the mystery aspect of the story. He integrates a lot of compelling flashbacks that add more fuel to the mystery. And he makes us think he’s going in one direction (the parents made the whole monsters thing up) to then using that against us, pulling the rug out from beneath our feet, and giving us this great reveal. That alone is worth a “worth the read.”

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Making gigantic thematic statements in your script (i.e. about race, about climate crisis, about the 1%) is not something you can do casually. You have to go all in and make your entire movie about that. You have to meticulously weave all of that stuff into every part of the story and characters. Because if you try to make some statement about the climate crisis in your script, it’s not going to affect us if it’s half-baked. This whole thing about the Aunt and him being half-plant — there wasn’t nearly enough there for us to understand the point that was being made. I bring this up because I see it quite a bit in scripts. Focus on telling a great story first. If you want to go that extra mile and make some grand statement about the world, that’s fine. But understand that it is going to be AN EXTRA MILE. It’s not going to be 8 or 9 feet. Which is the length of effort that most writers offer.