Genre: Comedy?

Premise: (from IMDB) When an all-powerful Superintelligence chooses to study average Carol Peters, the fate of the world hangs in the balance. As the A.I. decides to enslave, save or destroy humanity, it’s up to Carol to prove that people are worth saving.

About: A lot of people will focus on the terrible Rotten Tomatoes score of Superintelligence (26%). But Superintelligence actually achieves a rarity for any comedy, which is to get a worse audience score (23%) than critic score. Audiences are always more forgiving with comedy than critics. Which means this must be a really really really really really bad movie. Melissa McCarthy teams up, once again, with her husband, Ben Falcone, who directed the film and basically wrote it as well. This winning combo has created Tammy, Life of the Party, and The Boss.

Writer: Steve Mallory (but from what I understand, Falcone and McCarthy basically told the writer what to write)

Details: 2 hours of hell

First of all, you’re probably wondering why I’m reviewing this. I’ll tell you. This is one of the worst pieces of professional entertainment I’ve ever seen. Normally, I’d take that in and move on with my life. But I can’t. I can’t because if there’s one thing that bothers me about this business, it’s when someone with less-than-zero talent gets millions of dollars to make movies.

I’m not dumb. I understand that untalented people weasel their way into every industry. And, truth be told, they only make up about 10-15% of those industries. But their level of ineptitude is so extreme, that it always feels like a lot more than that. And Ben Falcone has to be the single most untalented writer and director I’ve ever seen get this many opportunities in Hollywood.

Of course, he has an ace up his sleeve. He’s married to Melissa McCarthy, who, ironically, is one of the most talented people in the business. I’m a huge Melissa McCarthy fan. Go to Youtube right now and search “SNL Melissa McCarthy.” There’s a reason no SNL host has more video views than her. She’s hilarious. And that’s what makes this all the more frustrating. Falcone’s lack of talent isn’t just dooming him. It’s taking down someone who actually has talent. Someone who should be making much better movies.

I’m going to try to summarize the plot of Superintelligence for you. But I’m giving you advance warning that the nonsensical nature of everything you’re about to read is going to make it sound like I didn’t understand it. No, this was the actual plot.

Carol Peters – the nicest person in the world – lives in Seattle and is trying to find a non-profit job. She’s having some trouble and, yet, that doesn’t seem to play into the plot at all. In other words, if she fails to get a job, it doesn’t sound like it will affect her life in any way.

Why does this matter? Because, later, the Superintelligence will buy Carol a 5 million dollar apartment, a 100,000 dollar car, and put 10 million in her bank account. But since Carol has never needed or wanted money, these developments feel random and unimportant. I’m sorry. I’m getting ahead of myself.

Out of nowhere, the first ever self-thinking AI contacts Carol, presenting itself as James Corden, since Corden is Carol’s favorite TV personality. The AI says it’s going to destroy humanity in 72 hours. Why? No idea. Never says. Probably best we not get into the specifics as we will then find out that if he destroys humanity, he also destroys himself, which would make absolutely no sense. But what in this movie does make sense?

First, AI James Corden says, he wants to learn about humanity. And he’s ID’d Carol as the perfect guinea pig. Why did he pick Carol specifically, though? No idea. To Falcone’s credit, this question is asked like 50 times in the movie. And yet, nobody answers it. Even AI James Corden answers it once and we don’t understand his explanation. ANYWAY!

To learn about humanity, AI James Corden asks Carol what she would do if she only had three days to live, since she does. She says make things right with her ex-boyfriend, George. Coincidentally, in the only attempt at writing an actual screenplay, George is moving to a new city in three days. So Carol better hurry up! Wait a minute. Do we even need a ticking time bomb with the George relationship if the earth is going to blow up in 3 days? Oh, who needs logic in screenwriting? MOVING ON!

As if understanding just how bad this script is, AI James Corden attempts to help out, giving himself a motivation for why he wants these two to be together. He wants to “better understand humanity” you see. And seeing if Carol can rekindle her relationship with George will somehow… achieve this? Maybe?

Quick plot summary break here cause I’m about to explode with anger. This script is so bad that I am positive it would finish fifth in voting an any Scriptshadow Amateur Showdown. That’s how bad this. It can’t even beat an average amateur screenplay. One of the primary issues with a bad script is that every screw is loose. It’s not clear why James Corden is going to blow up the world. It’s not clear why he wants Carol and George to rekindle their relationship. It’s not clear what Carol’s financial situation is or why she can be eternally jobless and not have to worry about money. Every single aspect of the script is vague. That’s bad writing. And for screenwriting this bad to be produced? Shame on these people. Seriously. Shame on them.

Sorry, I got distracted again. Where were we with the plot? Oh yeah, so the US Defense Department gets wind of the AI and is going to turn off the entire internet except for one small computer, trapping the AI there and then killing it, which is the only well thought out plot point in the entire movie. But AI James Corden gets wind of this and makes it impossible to turn him off.

However, at the last second, he has a change of heart when Carol does something unexpected (she doesn’t tell George about the impending doom). This makes AI James Corden realize that he has a lot to learn about humanity, so, okay fine, he’ll keep them around for a while. The End.

First of all, James Corden. You need to do better. You’re very talented but you’re George Clooney level at picking your projects. Have your agent start picking them for you.

Okay, maybe I can take a break from being so angry and use this opportunity to teach some lessons here. Unlikely but I’ll try.

Concept. When a concept is weak, nothing you write will matter. A concept is what forms your movie. It is the initial structural beam. Without a strong one, you’ll spend your entire script in “search mode,” where you’re searching for the story. Guess what, you won’t find it. You need to have done the work in the concept stage.

Superintelligence is not a concept. It’s a concept fragment. The only part that has concept potential is the superintelligence part. But then you need something that the superintelligence interrupts that is clever or ironic or has some form to it. A superintelligence studying an average person is not a concept. A superintelligence studying the dumbest person in the world still isn’t a movie-level concept, in my opinion, but it’s better. The irony of the highest intelligence trying to learn from the dumbest intelligence has some irony baked into it.

The biggest clue that this isn’t a concept is that you would have the exact same movie without the superintelligence part! This movie is about a woman who reconnects with an ex-boyfriend. You didn’t need the superintelligence for that. Like we already established, you didn’t even need the 72 hours before planetary destruction since George was moving out of town in 72 hours himself. EXACT. SAME. MOVIE.

Sure, you wouldn’t have had the AI buying Carol a car or a nice apartment. But like we established, those things had zero impact on our heroine. If our protagonist had been dirt poor and always wanted money, those purchases would’ve mattered. It could’ve been a Cinderella type situation or a “be careful what you wish for” film. But that’s how bad the screenwriting was here. They didn’t even know to marry the character situation to the concept. They were two completely different things that they attempted to mash up against each other the whole movie in some desperate attempt at comedy.

This shows what happens when there is no oversight, no pushback, no conflict, in development. That’s the thing I don’t understand with writers. They’re afraid of feedback. Afraid someone is going to tell them their idea sucks or their character sucks. BUT THAT’S EXACTLY WHAT YOU WANT!!! You want pushback. You want people to say, “No, that doesn’t work.” “No, that’s boring.’ Because then it forces you to go back in there and come up with something better. That’s how good movies are made.

The reason you can tell that nobody pushed back here is because everything that occurs in this movie occurs easily. Carol lives an easy life. We know the AI is never going to hurt Carol. We know Carol isn’t going to encounter much resistance getting back with George. There isn’t a lick of genuine conflict at any stage at any point in this movie.

It’s so badly written that I believe this script should be commemorated by all major film schools as the defining example of how not to write a screenplay. Every single choice in this script is wrong. I’m serious. Every one. If you made the exact opposite decision on every one of these story choices, you would likely come up with something great. That’s how misguided this was.

I don’t know how you can be this bad. You have to try to be this awful at something.

This goes down as one of the worst movies I’ve ever seen in my life.

[xxx] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you want to pay something off, you actually have to set it up. I didn’t know that people were so dumb that they’d need to be told this. But apparently, it’s the case with Ben Falcone. So there’s a scene around the midpoint where Carol takes George to a Seattle Mariners game and former Mariner great Ken Griffey Jr. comes to say hi to them and George nearly has a seizure. Ken Griffey Jr. is saying hi to him! Oh my God! This is amazing! He takes like 50 selfies with him and can’t stop talking to him. There’s only one problem with this moment. It was never set up. We were never told, before this moment, that George was a Ken Griffey Jr. fan. We were never told he was a Mariners fan. Heck, we were never even told he liked baseball!!! Which made this freakout session bizarre. Had a, you know, real screenwriter been in charge of this, they would’ve mentioned several times early on how big of a Mariners and Griffey Jr baseball fan George was, which would’ve helped this scene play a lot better.

The Scriptshadow Thanksgiving Newsletter has been sent! Check your Inbox, Spam, and Promotions folders! Review of a 7 figure spec sale. Some incredible advice about how to upgrade from amateur to professional. Black Friday consult deals. Go read it now!!!

Wait, what’s going on, Carson??? We just had an Amateur Showdown. Are you saying we’re having ANOTHER Amateur Showdown? Is that even legal?? You bet your tiny little tushy it is. Thanksgiving Weekend means we’re having an EXTRA LARGE Showdown with not FIVE, not SIX, but SEVEN ENTRIES. I’m doing that because we’ve got extra days which means more time for reading.

By the way, congrats to “Our Hero” writer, Colin O’Brien, who won the first Contest Showdown. For those who liked second place script, Inverted, Lee still has a chance at advancing, albeit behind the scenes if I like it enough to keep reading.

For those of you who don’t know what’s going on, I hosted a contest called The Last Great Screenplay Contest. After reading the first ten pages, I divided all the scripts into four piles. Yes, High Maybe, Low Maybe, and No. I then came up with the idea to take the top 20 (actually 22) Low Maybes and pit them against each other in four Amateur Showdowns.

The winning script in each Showdown will compete in a final Super Showdown, and that winner will advance to the Finals of the contest.

Confused?

Don’t worry. The rules are the same as any Amateur Showdown. Read as much of each entry as you can then vote for your favorite in the Comments Section. It’s VERY IMPORTANT THAT YOU VOTE. A screenwriter’s career may be on the line here. Votes are due in the Comments Section by Sunday evening at 11:59pm Pacific Time. The script with the most votes moves on to the Super Showdown.

Happy Thanksgiving and GOOD LUCK to all the contestants!

Title: Big Stick

Genre: 1 Hr. TV Drama

Logline: After a crushing fall from grace, a Boston cop/mom with an anxiety disorder retreats to her California surf community where her rogue investigation into a young girl’s murder teases a career do-over requiring the takedown of a powerful judge and her surf-hero son.

Title: Lucía’s Date for the Apocalypse

Genre: Apocalyptic Rom-Com.

Logline: After giving up on dating, a 25-year-old woman finds out the world is about to end and is offered two spots in a secret bunker that will save her from dying – the only thing she has to do is find the perfect man to repopulate the Earth with.

Title: The Fifth Return

Genre: Sci-fi

Logline: A US operative travels back in time to assassinate a Russian spy, but upon his return he discovers he failed his mission and has no recollection of his time spent in the past. Repeatedly sent back to finish the job while remembering none of it, he begins to suspect his handlers aren’t telling him the truth about his target. Think Memento as a time travel story.

Title: The Article

Genre: Contained Drama/Thriller

Logline: – When the CEO of a large media news company invites a troubled Male escort to her apartment……things are not as they seem.

Title: Club House

Genre: Thriller

Logline: A grieving mother invades the drug den her daughter was staying in and holds the residents hostage, determined to detox the group in the ultimate retribution for her daughter’s death by overdose.

Title: Bad Influence

Genre: Horror Comedy

Logline: After a popular child influencer gets possessed by the devil, her family, who rely on her income, struggle to keep her brand alive.

Title: The Island

Genre: Horror / Action

Logline: An NYPD emergency management specialist races against time to quarantine Manhattan after a zombie outbreak, only to discover that her teenage daughter is trapped somewhere on the island.

Genre: Comedy/Drama

Premise: Two scientists must go on a press tour to answer questions about an impending asteroid collision that will destroy all life on earth.

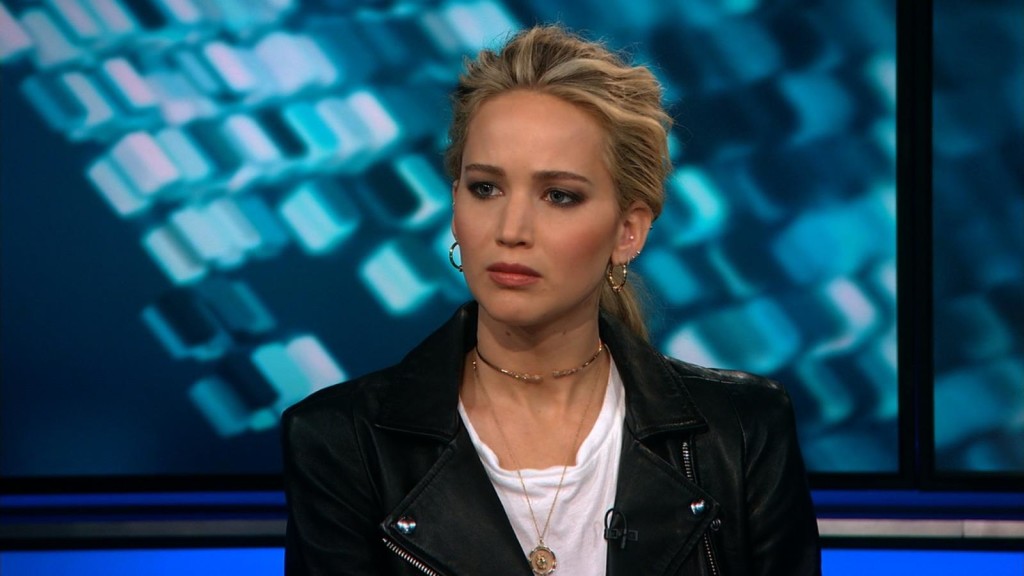

About: Big one today, guys. Some might even say it’s an extinction-level script. This is the big Adam McKay Netflix project that’s to star Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence, Jonah Hill, and Timothy Chalamet. Of his return to comedy, McKay said, “I don’t think it’s a ‘Step Brothers’-type of comedy. I would compare it more to somewhere between the Mike Judge stuff and ‘Wag the Dog.’ A hard funny satire is what we’re going for.”

Writer: Adam McKay

Details: 125 pages (Jan 2020 draft)

There aren’t too many scripts I get excited for these days. I’ve read so many screenplays and so many writers that I pretty much know what to expect when I open a script. That all changes today. Today’s screenplay combines a guy who I believe is one of the most talented in Hollywood, Adam McKay, with a unique idea. It also has an interesting cast. I mean, who would’ve thought that Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence would ever work together? I can’t think of two people more polar opposite. All of this implies that we’re getting something special. Famous last words, right? Let’s jump into it.

Scientist Kate Dibiasky works for tenured Michigan State professor Randall Mindy. During a party, Kate does a little work and, while tracking a comet, watches it collide with an asteroid, which then sends the asteroid on a collision course with earth.

Kate tells Randall, who confirms with everyone in the department that, yes, this thing is going to hit and destroy earth in six months. So they call the White House and get a meeting with the president, but to their dismay, the president says they want to sit on this information for three weeks, as they don’t want to throw any wild variables into the upcoming election.

Since every second passed is one more second the world isn’t stopping this asteroid, Kate and Randall go on a publicity tour to warn the world, in the hopes that it motivates our government to stop this thing. Except the exact opposite happens. Nobody takes them seriously. Even on the big shows, their interviews don’t trend. Everyone thinks their story is cute but, you know, not likely to be true.

As Kate gets angrier and angrier, Randall starts to cozy up with the White House, despite the fact that they’re not doing anything. Which makes Kate even angrier! Eventually, even the president can’t deny that this asteroid is coming for them. And so they FINALLY come up with a plan to send nukes at the thing and knock it off course.

But during the launch, just as the nuke delivery guy has made it to space, he TURNS AROUND. What’s happening, Kate demands. Well, it turns out the Elon Musk-like Peter Isherwell has discovered over 4 trillion dollars worth of gold and diamonds on the asteroid. He’s made a deal with the White House to use a series of drone-nukes that will latch onto the asteroid at strategic spots, blow it up into small pieces, which they can then mine from the ocean.

The problem with this plan is that the asteroid is now so close that if something goes wrong, they won’t have another shot to destroy the thing. Will they be able to pull this mission off? Or is everyone going to die because no one will acknowledge that this great big asteroid is really going to hit us?

One of the first questions that popped into my head while reading this was, “Why did Leonardo DiCaprio agree to make this movie?” The character of Randall isn’t like anything he usually does. I don’t remember the last time DiCaprio did comedy. I guess he’s sort of comedic in Tarantino’s movies. But I don’t think he’s ever done satire, has he?

Anyway, it all became clear when I realized this movie was an allegory for global warming. It’s about the fact that there’s this giant asteroid coming at us but nobody wants to “look up.” They all stare at the ground and ignore it in favor of the latest tick tock drama or what sexual misgiving the newest supreme court nominee engaged in 30 years ago. Global warming is DiCaprio’s passion (even if he likes to fly private jets everywhere). So if you share DiCaprio’s passion for this subject matter, you too, will probably enjoy this.

As a story, though, I had trouble getting into it. Satire has never been my thing. So that’s part of it. But the bigger part is that I didn’t care about Kate or Randall. And isn’t that what it always comes back to? It doesn’t matter if you have a great plot. It doesn’t matter if you’re passionate about the subject matter. If we’re uninterested (or even casually interested) in your characters, it’s not going to work.

Kate is one-note. All she does the whole time is be pissed off. That’s it. She tells people about the asteroid and when they don’t take it seriously she throws up her hands and says, “I’m done.” When you repeat the same beat over and over again for a character, that character becomes boring quickly.

Randall is a little more complex. He’s got this cheating scandal going on and he eventually turns to the dark side by cozying up with the president. But I never got a handle on him at all. At least with Kate, I could designate her. She was “the angry character.” You could give me all the time in the world and I still wouldn’t be able to tell you what kind of person Randall was.

This is why I remind writers, early on in their script, to figure out your character’s defining trait. Joker wants to fit in with the world. Jordan Belforte is addicted to excess. In Run, the mother loves her daughter too much. I don’t have any idea what Randall wants. And that hurts the story because if you have one character who’s too thin and another who’s undefined…. You don’t have a movie.

I’m going to make a grand assumption here and guess that McKay was so set on exploring his theme that he overlooked the people delivering it. This happens to all writers. Whenever we start a script, we have a specific reason we want to write it. Maybe it was the concept, a character, a theme, we want to tell a breakup story because we just went through a devastating breakup. Whatever it is, it’s often specific. What happens, though, is we develop a blindspot to everything else in the story. Those other variables aren’t the reason we wrote the story so we don’t care about them as much.

The script does have some funny moments. There’s a whole thread about “impact deniers.” Congress doesn’t initially approve the “Save The Planet Bill” due to partisan politics. The woman Randall has sex with gets off on being told the specific scientific ways the asteroid is going to destroy the planet. And there was the occasional funny line, such as this exchange in an early interview on a news show – Kate: “Well, it became apparent that the large asteroid’s orbit was changed by the hit, the collision… and it is now on a course to directly and catastrophically hit earth in just over five months.” Newsperson: “Now how big is this rock? Could it damage say, someone’s house?”

Also, even though I wasn’t that invested in the story, I did want to read til the end. There’s something to be said about a strong hook and wanting to see how that hook is resolved. I genuinely did not know, until the last 15 pages, if McKay would have earth get its s%$# together or kill everyone off. So at least I was uncertain where the story was going, which is more than I can say for most of the scripts I read.

But I don’t know, guys. I’m neutral on the script’s theme. The main characters were average at best. I didn’t laugh as much as I hoped to. And satire is one of my least favorite genres. When you add all those things together, you get my lukewarm response. It seems like a good movie to put on Netflix though. I’m not convinced something this off-center could have been produced for theatrical distribution. What do you think?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Spec screenwriters should stay away from the satire genre. It’s one of those genres, like dark comedy, where the execution bullseye is microscopically small. This tends to be a “showoff” genre anyway. A genre for those who like to prove how smart they are. But even if you’re good at it, the chances of you sticking the landing on one of these scripts is incredibly small. Therefore, I’d steer clear.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from IMDB) A homeschooled teenager begins to suspect her mother is keeping a dark secret from her.

About: This comes from the same guys who made the really cool “all-computer-screen” thriller, “Searching.” Quick fact that shows how frustrating the transition from page to screen is: Originally, this script had a big outdoor ending sequence. However, after shooting in Winnepeg for a few weeks, one of the coldest cities in the world, they were getting some complaints from their actors about the weather and therefore had to rewrite the entire ending so it was indoors! During production! So the next time you’re struggling to come up with an ending, remember that it could be a lot worse. You could be told that the ending you spent six months perfecting needs to be rewritten one week before shooting.

Writer: Aneesh Chaganty, Sev Ohanian

Details: 90 minutes

I feel bad for these guys because, after the huge success of Searching, this was supposed to get a major theatrical push, something that’s getting harder and harder to do for a movie of this size. However, the pandemic screwed all that up like it’s screwing everything up and “Run” went to streaming instead. But hey, that’s good for us, right? We don’t have to leave our couches to catch the latest buzz-worthy flick. Let’s take a look.

Diane and her 17 year old daughter, Chloe, have a peaceful life, all things considering. Chloe is a paraplegic who must get around in a wheelchair, which has forced Diane to be a full-time carer, but the two have a strong relationship as it’s clear Diane loves her daughter more than anything.

But lately, Chloe has been restless. She’s trying to get into college but every day she races to the mail, her mom beats her to it. It’s almost as if her mom is keeping mail from her. Maybe even an acceptance letter?

In addition to this, Chloe takes a LOT of medication. All supervised by her mom of course. And she’s beginning to wonder what this stuff is. Unfortunately, she’s not allowed to use the internet or even own a smart phone. Which limits her access to information.

Therefore, Chloe must get creative and look for opportunities when mom is gone. She finally uses a trip to the movies as an opportunity to say she has to go to the bathroom. She sneaks across the street to the pharmacy to ask what this pill is she’s been taking. She learns it’s a pill that causes people to lose feeling in their legs!

Now Chloe knows the truth. Her mom is a psycho. Which means she needs to escape. But that’s easier said than done. Especially because her mom is now on high alert (she discovered Chloe at the pharmacy at the last second).

Chloe will have to figure out a way to both escape their home and make her way into town, a several-mile drive with only one road to and from. Is that possible for a girl restricted by a wheelchair? And why do we get the sense that if Chloe doesn’t escape soon, her mother is going to do something a lot worse than paralyze her?

Let me start off by saying it’s scripts like this that got me into screenwriting in the first place.

You find a fun idea then build a narrative and series of scenes that best exploit that idea. That’s what “Run” is. You have this cool thriller concept where a teenage girl begins to suspect that her mother is holding her hostage. This necessitates our goal – escape. That goal is achieved by a series of scenes – our hero trying to escape. Those are the scenes that are going to make or break your script because those are the scenes that are fulfilling (or not fulfilling) the promise of your premise.

This was always my favorite part of writing. Coming up with those scenes. Debating, after you came up with one of those scenes, whether they were good enough. Whether they were working. Whether you could come up with something better.

“Run” does a pretty good job in this department. There’s a scene around the midpoint where Chloe has been locked inside her room. After her mother leaves the house, Chloe tries to escape by going out of her second-floor window, crawling along the roof, and getting back in through a window on the opposite side. In any other movie, this would be easy. But for someone without the use of her legs, it becomes a harrowing ordeal.

When she finally gets outside the house, she tries to wheel her way into town, and runs into the mailman on the country road. After he stops, she tells him everything. Only for her mom to pull up behind the mailman and attempt to convince him that her daughter is unwell and please just hand her over. I was on the edge of my seat hoping the mailman didn’t give in. Please, for the love of God, Mailman. Don’t give in!

But something I found that’s unique about this type of hostage situation – one where our captive has a lot of freedom (as opposed to when a serial killer has their captive chained up in a basement) is that it’s hard to imagine, with 24 hours in a day, 7 days in a week, that our captive couldn’t find a way out.

We set up some rules early on that Chloe doesn’t have an iPhone. She doesn’t have internet access. Which limits her ability to find out if these pills mom is giving her are poison. So there’s this scene where Chloe literally calls a random number and asks a busy man to look up something on the internet for her. And I’m thinking to myself, “I’m not sure this scene is a) believable, or b) the most logical way to answer this question.”

It was a reminder of how shaky the foundation of this setup was. Is it really that impossible to get information? The suspension of disbelief in this script was as fragile as cheap china. You got the sense that it could be shattered with even the smallest disturbance. And that definitely affected how much I believed what was going on.

For example, there’s this scene late in the movie where Chloe poisons herself to force her mom to take her to the hospital. And, presumably, as soon as she wakes up, she’s going to tell the doctors the truth about her mom. So Chaganty and Ohanian place this medical throat restriction device on Chloe so that even when she wakes up, she can’t speak yet. So Chloe mimes to the nurse she has something to say and the nurse finally gives her a crayon and a piece of paper. Chloe is finally going to be able to tell someone what her mom is doing to her!

Yet all I could think was: You’re saying that there isn’t going to be a single other second in this hospital where she could tell them the truth? Even under the most restrictive realistic scenario, you have to think that our heroine would be able to convey that her mom is dangerous.

For a movie like this to work, you want all of these illogical pockets to be eliminated. That’s why the mailman scene was the best in the movie. There weren’t any holes in it. We felt like this is really how it would’ve gone. Yes, if a mailman saw a frantic girl in a wheelchair trying to run away, he would stop to see if she was okay. Yes, if she told him her mother was imprisoning her, he would try to get her to the police. Yes, if the mom drove up at that moment, she would lie to him to get him to hand her over. Yes, if we were that mailman, we would listen to that mother, albeit skeptically. And, most important, we knew that if the mom won this argument, our heroine was screwed. That’s a strong scene right there no matter which way you slice it.

While the believability of the set pieces was hit and miss, I loved how the writers structured their script. The challenge with structuring these “captive” movies is that even the most elaborate escape is going to take, what? 25 minutes? 30 tops? So that’s your ending. Those last 25-30 pages. What do you do in the meantime? Especially because your hero will typically want to escape by the end of the first act.

What Chaganty and Ohanian do is they use the first quarter of the script as an investigation story. Chloe suspects her mom is giving her pills that are keeping her sick. So she needs to find out if that’s true. When she finds out they are, indeed, bad, we’re a little past the end of the first act.

Again, if you start the escape now (or even the planning), you’re going to need to make it last 75 pages. That’s impossible. So Chaganty and Ohanian do something clever. They have her plan and launch an escape, only for it to fail at the midpoint (the mailman scene). This places Chloe right back in the home, except under much more dire circumstances. The ruse is up. So there’s no reason for her mom to pretend anymore. Which means Chloe is in a lot more danger. Now she REALLY has to escape.

After Chloe assesses her situation, her mom returns from getting some suspicious materials and it looks like she’s going to double down on this “making Chloe sick” stuff. The two tussle and Chloe comes up with the plan to poison herself so her mom has to take her to the hospital. And now we have our final “escape” laid out for us. This is her last chance to run away from her mother forever. Structurally sound stuff!

“Run” is one of those movies that hums more than it sings. But it still comes up with a few melodies you can’t stop humming to yourself. Like but didn’t love!

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A great development for any script where your hero is held captive is the “FALSE ESCAPE” at the midpoint. Your hero does it! They successfully escape their captor! Only for, at the last possible second, the captor pulls some impossible move and captures them again, bringing them back to their prison. This not only helps you structurally. But it heightens the intensity of the second half because now the captor is enraged. They’re way more dangerous now than they were before, and escape truly feels impossible.

It’s an all-new all-different but-still-kinda-the-same Amateur Showdown! If you haven’t been to the site in a while, this showdown might be confusing, so let me give you the Cliff’s Notes version of what’s going on.

I hosted a screenplay contest called, The Last Great Screenplay Contest. I read the first ten pages of every entry and divided the scripts into four categories. Yes, High Maybe, Low Maybe, and No. Originally, I was only going to guarantee 10 more pages of reading to the Low Maybes. Then I came up with the idea that we would take the top 20 (actually 22) Low Maybes and pit them against each other in four Amateur Showdowns.

The winning script in each of the next four Showdowns will compete with each other in a final fifth-weekend Super Showdown, and that winner will advance to the Finals of the contest.

Confused?

Don’t worry. All you need to know is that this is like any other Amateur Showdown, except the stakes are much higher. So I need everyone here to read as much of each script as you can and vote for your favorite in the Comments Section by Sunday evening at 11:59pm Pacific Time. The script with the most votes moves on to the fifth and final Super Showdown.

I think you’re going to like this. A lot of the scripts that went into the Low Maybe pile had strong concepts, in a lot of instances stronger than the High Maybes. But for whatever reason, their first ten pages didn’t blow me away. By getting a second look from you, the readers of the site, I’m sure a script or two will emerge as a true contender.

Quick note. We’re doing a Plus-Sized Showdown next week starting on Wednesday that will have 7 scripts, since it’ll take place over the long Thanksgiving Weekend. So that Showdown should be extra fun.

Let’s get started with today’s entries. Good luck, everyone!

Title: Our Hero

Genre: Family Comedy

Logline: When 3 nerdy middle school kids discover the secret lair of a burned-out superhero; the world’s most powerful man agrees to be their friend in exchange for keeping his secret.

Title: Night of the Living

Genre: Horror

Logline: Years after humanity’s extinction, the idyllic life of suburban zombies is shattered when an outbreak of humans threatens their existence.

Title: Inverted

Genre: Horror

Logline: It’s 1997 and Jada just wants to have fun. But when the shadowy State of Burma opens its doors to outsiders for the first time, her new boyfriend’s idea of an adventure holiday turns into a horrifying fight for survival as they are stranded on a remote forbidden island harbouring a secret so diabolical, it’s been hidden from the world for centuries.

Title: Kelsey’s Crossing

Genre: Drama

Logline: When the helicopter she’s riding in over the Sonoran desert crashes in Mexico, the racist host of an anti-immigrant youtube channel has to rely on a group of migrants to survive the dangers and brutality of the desert and help her travel 40 miles to get back to American soil.

Title: Ambrosia

Genre: Time Travel/Heist

Logline: Three anxiety-ridden young adults discover an experimental drug that allows them to time travel back 36 hours after each overdose. As the side effects intensify and their tolerance builds, each time travel back becomes reduced (16 hours, 8 hours, etc), but they keep going back anyways to perfect a bank robbery. Meanwhile, the town’s leading detective chases them down.