Search Results for: the wall

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: A small team of astronauts go out into the universe in search of potential new homes for the inhabitants of earth, who are experiencing a rapidly dying world.

About: Interstellar opened this weekend and did quite well at the box office, finishing in second place (with 50 million) to Big Hero 6 (hey, who’s going to beat an animated Disney movie at the box office?). The project was originally going to be directed by Steven Spielberg many years back (isn’t every movie at some point?). After he left, writer Jonathan Nolan kept working on the script, eventually convincing his brother to direct it.

Writers: Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan

Details: 170 minutes

People seem to be all over the map on this one.

Some critics believe the film is laughable. Yet a lot of commenters (on various sites) have called it a masterpiece.

It seems like you have to either love or hate Interstellar. And as much as I want to fall on one side or the other to give the film/script that definitive stamp of good or bad, the reality is, this is a very mixed bag.

I do want to state the obvious though. Regardless of the quality of the film, Christopher Nolan is doing God’s work. The man is making big-budget original movies when he could be getting paid five times as much doing what everyone else in this town is doing – riding the superhero gravy train. Yeah yeah, he did Batman. But it was clear he didn’t want to make the third one. Which means between this and Inception, the last 7 years or so have been dedicated to infusing the box office with some of the only big-budget original entertainment out there.

Before we get into the juicy details, here’s a breakdown of the plot for those who haven’t seen the film. Coop is a former astronaut in a near-future world that’s running out of food. He somehow stumbles across a hidden NASA base, whose president informs him only hours after he arrives, that they need him to lead a mission to save the world.

They found a wormhole near Saturn that allows them to jump to another galaxy. There are three potentially habitable worlds in this galaxy. Coop is to head a small team that will check out these worlds, and hopefully verify that one is perfect for us to colonize. Coop has to leave his son and daughter for the mission, who we periodically check back in on, all the way into adulthood.

While the first act (which establishes the state of the world) is effective, it’s also really clunky. Early on we get a strange scene where Coop is driving with his daughter (Murph) and spots an “Indian drone” flying around. They chase it through the cornfields (how does a jeep going 30 miles an hour through a cornfield keep up with a drone that’s going 100 miles an hour?).

Apparently, according to Coop, the solar cells on this drone will “power the farm” for years. So they chase it and somehow hack into it with a computer and land it. The scene’s intent is a sweet one – a unique bonding moment between father and daughter – but because the drone causes so many frustrating questions, it impedes upon this intent. It’s an Indian drone? What is it doing in America? Also, if its solar panels can “power the farm for a year,” how come we never see these “solar panels” in action? In fact, I didn’t see any solar panels on the drone at all.

This is followed by one of the most confusing moments in the script. During a dust storm, Murph forgets to close her bedroom window. Dust then flies in and creates a pattern on the floor that Coop believes is a set of coordinates that he must travel to and check out (uh, sure). So he and Murph get in a car, drive all night, until they get to some private land that turns out to be, of all places, NASA, which has been hiding underground for years.

NASA is now run by Cooper’s old boss, Professor Brand, who informs Coop that they’re launching a mission in a week to look for new planets. And, oh yeah, since Cooper is the best astronaut in the world, he wants him to pilot the mission!

Whoa whoa whoa, what???

In old screenwriting circles, this is called: “lazy fucking writing.” So let me get this straight. Cooper finds a space institution he didn’t know still existed through dust coordinates in his daughter’s bedroom, and minutes after he arrives, he’s being asked to join their mission that leaves in a week??? Might that be the single biggest coincidence in the history of the world?

Like many of you, I wondered, if Coop is the best pilot in the world, why didn’t Brand go get him himself? This is “explained” in one of the many cheat lines in the screenplay, with Brand saying something to the effect of, “We didn’t even know you were still alive.” Oh give me a fucking break. You’re about to travel through a wormhole to another galaxy to explore three new planets and you didn’t think to check if the greatest astronaut in the history of the planet was still around?

Anyway.

This is followed by one of Nolan’s biggest weaknesses: clunky exposition. We’re given an extremely elaborate mission breakdown that includes plan As and plan Bs, jumping through wormholes, 12 total worlds, 3 promising worlds, past missions, black holes, singularities, time slippage, one way communication, and, of course, Interstellar’s favorite topic – gravity.

This is where things get really convoluted. Apparently, Professor Brand is working on some sort of gravity displacement technology that will allow him to raise NASA up into space, because the underground NASA structure is also doubling as (get this) a space station. He tells Coop that when he comes back, he’ll have solved this gravity problem, which, I think, means he’ll be able to use gravity to send the whole of earth’s population through the wormhole to one of these new worlds.

Uh, come again?

Anyway, once we get into space, the movie finally starts coming together. Gone are many of the convoluted plot points, and we’re finally able to just… breathe. Or, more appropriately, explore. Actually, that’s not 100% true. There are still some convoluted plot points and exposition, but now Nolan can use our ignorance of space, time, and the universe against us. I don’t know if a Black Hole outer-sphere really makes 1 hour the equivalent of 7 earth years, but it sure sounds cool so I go along with it.

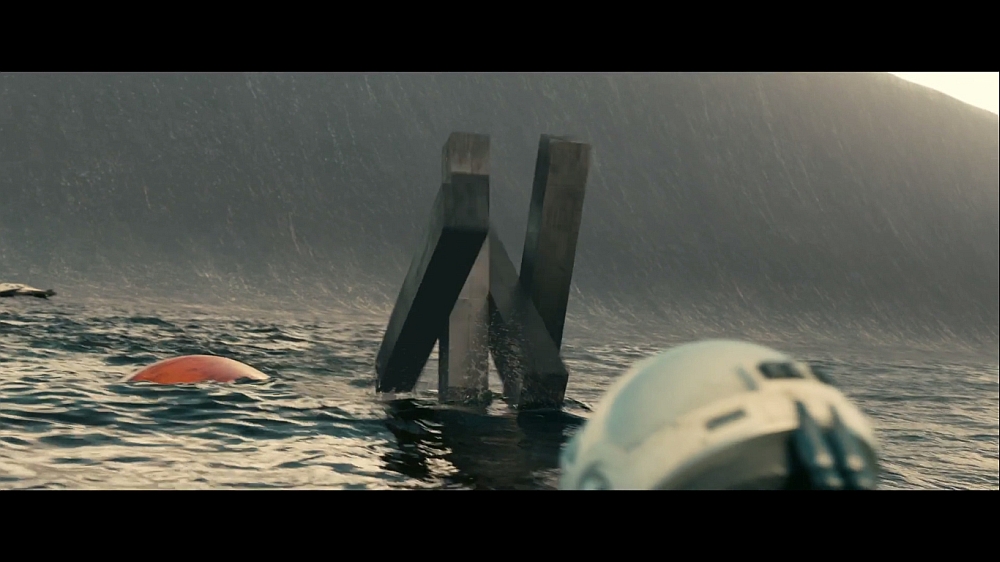

But the exploration of the worlds really was cool. And the worlds allowed the film’s real star to emerge, TARS. If I’m going to take the writers to town for their laziness, I have to give them props for their creativity. TARS was the most original and lovable droid since R2-D2 and C3PO. He was unique and fun and unexpectedly versatile. When he goes to save Brand (Professor Brand’s daughter – played by Anne Hathaway) on that water planet as the tidal wave is approaching and he transforms into some windmill apparatus to speed through the water, it was one of those moments of pure movie magic.

This brings us to one of the most hotly debated segments in the movie (surprise casting spoiler), the Matt Damon sequence. From what I gather, the people who hated the rest of the movie loved this moment. And the people who loved the rest of the movie hated this moment. That’s probably because the Damon sequence was an entirely different genre from the rest of the film – it was a thriller.

I liked it, even if it did feel a bit out of place. The sadness behind that character is what sold it for me. Him being there for so long, all alone. It brings up questions that it sounds like we’ll be dealing with soon – as there’s this “mission to Mars” plan that will entail sending a single person to die on the planet. Along with the other crew member on the previous planet trip having to wait 23 years for Coop and Brand to return (every 1 hour on the water planet equaled 7 years in orbit), there were some really fascinating questions posed here about time and loneliness and its effect on people.

TARS needs his own movie! Preferably a team-up with John Wick’s dog.

TARS needs his own movie! Preferably a team-up with John Wick’s dog.

Up until this point in the film, I’d probably give Interstellar a double worth the watch. Despite is flaws, its pure grandiosity was magnetic. I think it’s sad that we aren’t pioneers anymore. I was more than happy for Christopher Nolan to show me what it would be like to explore again, even if it was a fictional experience.

And then…

And then Christopher and Jonathan Nolan start the bullshitting. Either that or they got lazy or they simply ran out of time. Because everything that happens in the last 30 minutes of this movie is pure hogwash. It feels like a couple of stoned college seniors forgot their term paper was due the next day, and scrambled to write the last 7 pages in a drug-induced stupor.

I mean come on. Cooper goes into the center of a black hole, encounters a “five-dimensional reality within a three-dimensional space,” which amounts to an infinite recreation of his daughter’s bedroom. In order to stop himself from going on this mission in the first place, he sends binary code through the second hand of an identical watch he gave his daughter…

I mean do I even need to go on? This is such “wrote myself into a corner now I’m going to bullshit my way out of it” I don’t even know what to say. With supernatural set-ups and payoffs, there’s something you need to establish that I call the “Immaculate Connection.” This is where you give the reader enough information so that the payoff’s arrival makes sense.

The Force is a good example. The Force is explained to us. We see it in action numerous times. This helps us understand how it works. Therefore, when Luke uses the Force at the end to destroy the Death Star, it makes sense to us.

This was the opposite of that. This was, “throw as much psychobabble bullshit at the wall as possible in the hopes that the viewer gets distracted enough that whatever vaguely connected payoff we throw at them will be sufficient.” I HATE IT when writers try to bullshit an audience. It’s your due diligence as a writer to give the viewer a satisfactory ending that makes sense within the construct of the imaginary world you’ve created.

I love that IGN (very politely I may add) called Jonathan out on his bullshit in an interview question. And Nolan’s answer verifies my suspicions. He made all this shit up on the fly. Here’s what IGN asked: “So when they find Cooper they are by Saturn again and they have these very advanced ships. So I guess I wondered: Did it take them many years to build the ships? If so, where did they get the resources? Was it on a new planet or on a dying Earth? Also, how did they survive on Earth long enough to build such ships? Or had they gone and colonized in the far reaches of space? In another galaxy? Had they found Brand and very quickly and impressively rebuilt their culture? And if they had gone and colonized, why were they at Saturn again? Right at that exact moment? What are they hoping to find there? If they had found Brand, then she would now be old too, wouldn’t she? Yet, Murph is suggesting that her father go find Brand so that they can build a colony together – which indicates that Cooper and Brand would still be the same age and compatriots. And that they would remain so once he found her in that small ship. Can you explain what’s going on in that scene? And just the science behind it?” Just the fact that someone has to ask a question this complicated shows how messy and thrown together this ending was. Nolan’s response starts with: “I’m happy to try — although I feel like it’s for the viewer to enjoy and trust that we spent and awful lot of time thinking about these things, as we did.” Of course. The old, “It’s up to the viewer.” That works when you’ve created a carefully thought out story. It’s a cop-out when you’ve belittled the audience by giving them a combination of psychobabble and nonsense for the past 30 minutes (you can read the rest of the interview here).

Am I being too harsh on Interstellar? Probably. But I believe Christopher Nolan should be held to a higher standard. He’s shooting for the stars here. So you need to be judged on what your goal was. The goal was a smart epic look at space travel. That’s not what we got. We got an imperfect movie with moments of brilliance, marred by moments of colossal laziness.

MOVIE RATING:

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

SCREENPLAY RATING:

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Cheat lines.” These are lines writers use to cover story problems in their script. Why didn’t they go looking for the greatest astronaut on the planet to head their mission in Interstellar? “We didn’t even know you were still alive.” Why in the world would they not think Coop was alive? Was there any evidence to this theory? What’s the harm in doing your homework and at least trying (it turns out he was only a few hours away!)? A well laid-out plot does not need the writer to constantly cover for it. Your use of a cheat line is indicative of bigger problems in your story. Instead of trying to bullshit the audience with a cheap cover line, go back and fix the underlying problem that’s causing you to cheat in the first place (in other words, it would’ve made much more sense for Professor Brand to show up on Coop’s doorstep and ask him to join his mission).

At 29, Adi Shankar is one of the hottest young producers in town and one of the few guys who isn’t afraid to produce risky R-rated material. His credits include The Grey, Dredd, Lone Survivor, and A Walk Among The Tombstones. He’s also releasing one of my favorite scripts, The Voices, next year.

Shankar’s counter-culture approach extends to the web as well, where he’s produced the short film, “Punisher: Dirty Laundry,” starring Thomas Jane and Ron Pearlman, and “Venom: Truth in Journalism.” His newest offering is the animated dark comedy mini-series, “Judge Dredd: Superfiend,” which you can go watch right now!

SS: Before we get into writing, I’ve always admired your ability to make these risky R-rated films in an industry that’s typically afraid of that space. How do you pull it off?

AS: Most companies egregiously overspend on overhead. I believe in a lean, tight-knit team, and it allows me to be cost effective in all my decision-making and affords me the financial freedom to make “riskier” films.

SS: Okay, moving on to my bread and butter. I always talk to writers here on Scriptshadow from a writing perspective. But producers see the craft differently. From your side of the wall, what advice can you give writers just starting out?

AS:

1. When starting out, don’t be discouraged by people with the “9 to 5” jobs. They are the ones who urge you to “be realistic,” goad you as you attempt to understand yourself, and bring you down during your sporadic, minor, yet intangible victories. Take solace in the fact that these “9 to 5-ers” will get their minds blown when they see Katy Perry (or equivalent) at a restaurant one day and it will become the single defining moment of their lives, while you are attempting to add to the discourse of the culture.

2. Write every single day. If you don’t, writing will always just be your hobby. (Note: This doesn’t mean quitting your job)

3. You should read 200 “great” professional screenplays before you start writing so that you know what you are aspiring to be. The resources (scripts, interviews, trades, etc.) you have access to today as a beginning screenwriter are unparalleled and were only available to previous generations by becoming someone’s bitch. For the first time, you don’t even need to live in Los Angeles to be a screenwriter or to have your work read.

4. Follow the plethora of online recourses that weren’t available to past generations i.e Blacklist and the tracking boards, to see what’s selling, what’s getting heat and not selling, what’s getting acclaim, and what’s getting acclaim but not selling. This will inform your understanding of the marketplace and the business of screenwriting.

5. Write and produce for the Internet. It blows my mind that more people aren’t attempting to build a web footprint. Check out NEXT TIME ON LONNY it’s simple, smart, funny and is a blueprint for anyone who aspires to create.

SS: What about writers who are closer to the mid-level? These might be writers on the verge of breaking in or who have just punctured the lower levels of the industry. Any advice for them?

AS: The biggest misconception you have to psychologically fight is this idea that once you cross a certain imaginary threshold in your career you’ll feel “made.” You’ll never feel truly “made.” While, like any rote skill, things do get easier over time, you struggle consistently at any level and actually feel more not less pain at every higher rung on the proverbial ladder.

This industry is convoluted and hard for everyone: Whether you’re a novice writer or Robert Towne, a beginning actor or Russell Crowe, an assistant at the mailroom or Stacy Sneider there is always arbitrary red tape, infuriating walls built by insecure middlemen, and some asshole that just wants to fuck you over for the sake of fucking you over. You are constantly living with a damoclean sword over your head and a lottery ticket in your hand, one bad decision away from being black balled and one great sentence away from becoming the next big thing.

SS: Everybody’s trying to get their idea/script/project to the guy who’s able to say “yes” and the movie is greenlit. You’re occasionally that guy. In your best estimation, what do you need from a screenplay to give it that green light? What makes you say “yes?”

AS: Two things need to happen:

1. I need to respond to it creatively. (Note: I detest the routine and respond to material that is unconventional).

2. The market needs to respond to it financially.

As you can imagine 1 & 2 are almost always at odds with one another.

To be specific, by the “market” I don’t mean the movie-going public. Unless you are operating at the highest of levels (aka the Chris Nolan, Spielberg, JJ Abrams level), producers/directors don’t make movies for audiences, we make movies for distributors, and are beholden to what distributors believe audiences want (read: the last successful movie).

Second only to the inability of distributors to match a prospective customer with a specific product in a cost effective manner, the biggest problem that our industry needs to solve is the issue of access. Information is a commodity to the detriment of the business.

So my advice to writers: Figure out what the market wants and write the best version of that as quickly as you can before the market changes. For example, in 2008 it was quirky indie comedies, in 2010 it was $25-30 million dollar action movies, in 2012 it was $3 million dollar horror movies. Pretty soon the $7-12 million range, which for years had been the “no mans land,” is going to be the independent sweet spot.

SS: This leads me to a question I’ve always had. This industry is actor and director driven. If you get a big actor or director attached to your script, the project has a much better chance of getting made. So as a writer, should I be trying to find ways to get actors and directors to read my script so they’ll attach themselves, THEN come to you? Or should I come to you first and let you use your relationships with actors and directors to put that project together?

AS: It depends. I prefer STD free scripts, but sometimes if the attachments are so great then everyone is obviously going to pay more attention. Again, it depends on the producer and the genre of the script.

By and large I’ve found attachments for the sake of attachments to be a detriment. I once read a script that I thought was great but the manager insisted that a much hated director had to be attached to direct. That manager ultimately screwed the writers by making their very makeable, highly marketable script instantly un-makeable due to a bogus attachment. The marketplace moved on and the window of opportunity to make the film passed.

Also, when you’re attaching someone, realize that you are getting in business with the person, that person’s reputation within the industry, and reputation with the potential buyers for your project, not their credits.

SS: You sell your movies to many foreign territories, which is a way to fund your movies (or most of them) before they even get made. Film is becoming more and more of a global business. Should screenwriters be accounting for that in their screenplays? Should we be writing differently? How does one write for a “global audience?”

AS: Don’t worry about this. Just try to tell a really great story. The more you get caught up in trying to retrofit a human story into something that will “sell globally” the more you risk diluting your material.

SS: You were telling me about a project awhile back, an idea you came up with. And you said you went out and found a writer for that. How does a writer (say, a writer reading this right now) become the person you call to write your movie? How does he get in that room with you?

AS:

Step 1: In that particular instance the writer had written the last movie by the director whom I was developing the idea with. The brutal reality is that writers almost always get hired for an assignment because of a working relationship.

Step 2: When I call writer’s representatives, it’s preferable that they be “user friendly.” I’ve passed on working with so many talented writers because I thought their agent or manager was a cheese dick and was going to cause problems down the road.

Best blanket advice I can give to an up-and-coming writer:

Find a talented director at “your level” and partner with them and become “their writer” and start operating as a team (See: Wigard, Adam & Barrett, Simon). So many talented directors are in dire need of writer/producers to execute their wonderful ideas and more importantly for a creative partner who isn’t a cornball producer trying to pull a silver dollar out from behind their ear. This journey in 2014 is now too complicated and frankly impossible to do alone, so build a collective.

To be a douche and quote myself:

“Hollywood is undergoing a massive decentralization right now, caused by the ongoing collapse of the studio system and the rampant greed of the 90’s. It means that collectives of people who can consistently and autonomously deliver a product will have an advantage. They will help you sift through all the crap Hollywood throws at you, and more importantly give you the kind of creative autonomy that today’s non-celebrity filmmakers can only dream of.”

SS: Is it important that a writer be “good in the room” with you? Do you have to feel a chemistry or a certain energy and knowledge from them to work with them? Or do you only care about how good of a writer they are?

AS: Being good in the room doesn’t matter. I don’t want the guy who sells me the car to design and build the car too. I’m also not looking for a friend, girlfriend, roommate, drinking buddy, flip cup or beer pong partner. Humility, writing skills, and general insight about life that can be retrofitted into a screenplay are all that matter. I do meet many writers who are whiney and unloved and complain about “how unfair the industry is” and I generally want to bitch slap them … so don’t be that guy.

SS: I ask a lot of producers what they want from a script, and they almost always say, “I’m just looking for something great.” Is it really that easy? Or are there more factors involved?

AS: It’s that simple. We just want great material. Great material will attract a great director and that package will attract “bankable” (note: as an actor myself that word pisses me off) actors. It will make distributors fight over the distribution rights. Give me SOURCE CODE and I’ll produce and deliver you a finished film via text message faster than you can say Punisher Dirty Laundry.

SS: Does a writer need an agent for you to read their scripts? If you do receive scripts outside of agents, where do they come from?

AS: It’s a legal grey area. I desperately want to discover a great script from under a rock but legal reasons make it challenging.

Traditionally, success in this business has been proportional to one’s access to information. In their inevitable next evolution, online screenplay resources like ScriptShadow, Trigger Street, and Blacklist are very shortly going to revolutionize the way producers/actors/directors access material and democratize the green lighting process.

Before the Internet, an agent had the ability take a script off the shelf and present it as brand new. Tracking boards made the spec market efficient. Blogging made it possible for one to dissect material and allowed the industry to congregate behind risky but great material. The next tectonic shift will be numerically driven and force an egalitarian more “crowd sourced” process to the chaotic status quo.

On the issue of agents, keep in mind that reps are useless unless you have a career spark. To be clear, it’s on you at every juncture in your career to create a spark for yourself. If you are unrepped and looking for your big break right now the web stuff is the best platform to create a spark. What reps are really good at is turning a spark into a flame and the best reps will help convert that flame into a forest fire (see: Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper).

SS: Finally, we all know Hollywood prefers intellectual property that’s already proven. Since all screenwriters are poor and can’t afford to buy flashy intellectual property, what can they do to compete with these guys?

You bring up an interesting point. In television, the writers are the producers. This should be the case in the movie business as well, as it would eliminate a lot of the infrastructural problems we face.

A trend I’ve noticed is that once writers become deemed “professional writers” many take the mentality of “I need to be paid to write.” While I can sympathize, the fact of the matter is great screenplays are the lifeblood of this industry. If you have a great story that must be told … fucking write it.

It doesn’t make sense to waste time waiting for some jerk off producer or studio to “buy your idea.” Own it, control it, and if you really are that good you may have just written the next DALLAS BUYERS CLUB, PRISONERS, or LOW DWELLER (OUT OF THE FURNACE). Every major movie star and every major director needs a “next movie” and even those we have deemed gods at the moment are beholden to access to great material and are at the mercy of those who control it. Unencumbered scripts are easier to make.

Horror has a certain power over me that I can’t explain. So primal is my need to be scared that I will watch every studio horror film released. It’s why I went to see Annabelle. It’s why I’m going to see Ouija this weekend. Do I think Ouija is going to be a good film? Hmmm. Will Renee Zellweger ever look like herself again? The answer to both questions is, of course, no. But if I can get just a couple of scares out of the viewing, I’ll be happy.

Having said that, deep down, I’m always hoping that this is going to be “the one,” that rare horror movie that doesn’t just titillate, but resonates. After reading the awesome “February” yesterday, I asked myself, “What is it that makes a good horror script?” How do you achieve that rare feat of going beyond the scares and giving the reader a fully-rounded experience, like how one feels after watching “The Exorcist” or “The Sixth Sense?”

I don’t know. But looking back at the horror films/shows/scripts I’ve liked recently (The Walking Dead, Mama, Honeymoon) and comparing them to the ones I hated (Annabelle, Oculus), there do seem to be some consistent threads in each. So I wanted to highlight those so you horror writers can give this thing a proper go. This shouldn’t be considered a final list. I’m far from a horror aficionado. But these should give you a baseline on how to get horror right.

Go in with higher expectations – One of the problems plaguing horror is it’s the genre with the lowest expectations. People see horror mostly as a vehicle to throw cheap scares and gore at the screen. Writers pick up on this and, as a result, set the bar low for themselves. Once you’ve done this, you’ve basically guaranteed your script will be bad. Treat horror just like you would a drama. Aim high and deep. I don’t care if you’re “only” writing a slasher movie. Try to make it the best slasher movie ever. There are few things as depressing as reading a lazily written horror script.

Deep characters – Remember this simple rule. If we don’t care about the characters (love’em or hate’em), we won’t care what happens when they’re put in danger. You cannot illicit fear from apathy. The reader must have a strong feeling about the characters one way or the other. So before you write your horror script, spend a LOT of time building your characters. Figure out their backstories, their fears, their flaws, their broken relationships. What is it they need to overcome in this journey? The more you build into your character, the more likely we’ll care about them.

Tie the scares to the characters – The horror and the scares in your screenplay should not be mutually exclusive. They should be designed around one another. In other words, try to connect your character’s fear to the horror at hand. In Mama, the step-mother’s fear is love, is getting close to these children. The scares in the movie then, surround this ghost mother who wants the girls back. The step-mother will have to learn to love the girls in order to save them. The closer you can connect the scares and the character’s own issues, the more impact the scares will have.

Original scares – Cliché scares are one of the most abused practices in horror writing. And this goes back to the first tip. Expectations need to be higher. If you’ve seen the scare before, DON’T USE IT. Or, at the very least, find a way to update it. One of the things that really annoyed me about Annabelle was the old-timey record player that kept turning on. Give. Me. A break. This is pure laziness. The Walking Dead is really good at spinning old cliches. We’ve all seen the scene where our characters have to pick up supplies at the supermarket but zombies are lurking about. Well, two seasons ago, they had a scene where the ceiling crashed in and all the zombies on the roof dropped down, trapping our heroes. Or this season, they had a scene where they had to get the food in a flooded storage basement, adding a unique challenge (walking in waste-high water) and type of zombie (a “floatie”). It’s never easy to sit down and challenge yourself for hours to come up with something new and original. You feel like you should be writing instead, and that you’re wasting time. But when you put in that extra effort and DO find an original scare or a new spin on an old scare, it makes your script so much better.

Be truthful – Don’t force illogical truths into your story just to get scares. When you do that, you’re being dishonest and bending the rules of reality to fit your plot. Instead, you should always try and be truthful, to offer reality. The more realistic the world you create is, the more we’re going to suspend our disbelief. One of the biggest problems with Annabelle was that the doll was the creepiest fucking doll in the universe. It looked like the picture-perfect version of a what a movie possessed doll would look like (and nothing like the actual doll it was based on). If that was it, I’d say fine. But where you’re being dishonest is having the mother character want it in the first place. Who in their right mind would want a doll like this? “Hey hubby? Can you grab me the creepiest fucking doll you can find for my collection?” Yeah right. There was nothing truthful about this plot point, and if you lie like this to the audience too many times, they call you on your bullshit and check out.

Atmosphere – You saw me talking about this yesterday with “February.” Horror is about atmosphere. It’s never just about walking into a room. It’s about the mood in the room. It’s about what’s creating that mood. Are the heating pipes banging obnoxiously behind the walls? Are there ice crystals forming on the window due to the -12 degree temperatures outside? Is your hero scratching at that annoying rash on his arm that won’t go away? Don’t be afraid to show those dead flakes of skin falling to the ground either. Atmosphere can be your best friend in a horror script when done right.

Loss of control – One of the scariest feelings for most people is a complete loss of control. Prey on this fear. As your story maneuvers through its plot, your characters should have less and less control over the situation. And at some point, they should have no control at all. They should feel completely helpless. Look at movies like The Exorcist, Human Centipede, and the little known Aussie film, The Loved Ones. Our fear is based almost exclusively on the helplessness of the main characters.

Build – Horror movies never seem to work when you jump into the scares right away. They need to be groomed and raised. They need to grow up over the course of the film. In other words, you want to BUILD UP to the scares. Look at Paranormal Activity, one of the most successful horror films of all time. That movie goes about three-quarters of its running time before a genuine scare occurs. Before that, it’s mainly a series of small building scares. As a general rule, try to design the first 60-70% of your movie as creepy and the last 30-40% as scary.

The prelude to the scare is often more scary than the scare itself (aka “Milkage”) – A good solid scare is wonderful. But if that’s all there is, you’ve entertained your audience for all of one second. The real key to scaring is chronicling what happens BEFORE the scare. That’s where the gold is, as you can draw the feeling of fear out. As such, you should be designing scares that have a great lead-up, a period of “milkage” if you will. One of my favorite script scares is still in the original draft of The Conjuring, which they ended up cutting. In it, our main character is inside the wall crawlspace, and has found a hole that goes into the basement. There’s a rope coming out of the hole. She starts pulling it. And pulling it. And pulling it. Our imagination is so wrapped up in what’s at the end of that rope, we don’t realize that it’s the prelude to this reveal that’s really scaring us. Of course, a great reveal at the end doesn’t hurt either (in this case, the noose around the witch’s head).

An impending sense of doom – We should feel like bad things are coming for our characters in the future. This should stress us out. We should never feel comfortable in a horror film, like things are going to be okay. We should always feel like it’s going to get worse, that doom is just around the corner.

Plenty of you out there eat, sleep, and breathe horror. And I’m interested to hear your thoughts on my list. Beyond what I’ve noted, what do you think makes a good horror film? Share your tips with the rest of us.

Genre: Drama

Premise: (from Black List) Based on a true story, Dale Julin (a low-level Fresno affiliate morning show host) stumbles upon the biggest story of his life – and though he has reached the midpoint of his career without ever being a “real journalist” – risks his safety and his marriage to uncover the truth that a small Atomic bomb exploded in Central Valley California during the Korean War – a secret that had been hidden for decades.

About: I decided to go BACK to the Black List for today’s script. “Time and Temperature” finished on the low end of the list with 7 votes. The writer, Nick Santora, is a big deal in the TV world. He’s written for The Sopranos, Law & Order, Prison Break, and most recently created the CBS show, Scorpion. Santora did something I’ve claimed on this site is impossible. He won a screenplay contest (the New York International Film Festival Screenplay Contest) with his FIRST screenplay. Off that win, he was hired to write an episode of The Sopranos. Please don’t throw your laptops against the wall. Time and Temperature will be Santora’s directing debut. Ivan Reitman is producing the film.

Writer: Nick Santora

Details: 120 pages (5/31/13 draft)

On Monday we were talking about what makes an idea big enough to be a movie. In this day and age, unless you’re specifically aiming for the indie market and an Itunes release, you have to think big. And when I read the premise for this on the Black List, all I could think was, that doesn’t sound big enough to be a movie.

First of all, you have the word “small” in your logline. That’s not a good word to have in any logline. Movies are supposed to be big. The events that happen within them need to feel huge (unless you’re going for that indie market). Who cares about a “small atomic bomb?” It sounds insignificant in the grand scheme of things.

Tack onto that the Korean War. The Korean War?? The Korean War is like the forgotten stepchild of the Vietnam War. Nobody remembers the Korean War. Already this is looking bad. I mean, if you told me this was about a Japanese-American journalist in 1945 who found out that the U.S. was going to drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima 2 days ahead of time and he had to decide whether to report about it or not… now you have yourselves a story. A mini-atomic bomb that didn’t even get dropped on anyone 60 years ago? Is that really a movie? I pray it is. Or else these are going to be a looooong 120 pages.

Time and Temperature is set in 1989 and focuses on local news show host Dale Julin. Dale’s specialty is doing those fluff-pieces like testing out the local Clown School. Which, in a way, is appropriate, since Dale’s career so far can be described as one giant pie in the face. He’s 44 years old, the age most people settle down into who they are. But Dale’s just not satisfied. He wants something more.

That opportunity presents itself when he takes his wife and two daughters to see his dad at the Travis Air Force base, where Dale grew up. His dad was a war hero, which is like adding flashing lights to Dale’s failures. While home, he learns that an old friend’s daughter just died of a rare form of cancer. But the kicker is that the man’s niece died from the same type of cancer two years ago.

His journalistic instincts kicking in, Dale starts asking around, and learns that dozens of people on the base have gotten cancer over the years. And it all came after a 1950 B-2 Bomber, which was headed to Korea to drop bombs, crashed on take-off. Dale gets the idea that this plane was carrying something with more kick than your average bomb, and he wants to prove it.

So he concocts a pretend reason to interview everyone on the base (a birthday bit for his dad) and just keeps digging. Like any good investigation story, there are some false leads, some interesting twists, and a lot of hardship, such as Dale losing touch with his family along the way. But he continues to hold onto the idea that it’s true, and that the government has been covering it up for 40 years.

It turns out there’s more to this story than just the bomb, and it’s something I wish they would’ve included in the logline (although that logline needs a meat cleaver chopping as it is). It’s not just the bomb that’s the issue. It’s that the bomb’s detonation has caused many people living on Travis Base to contract cancer.

In that sense, it’s kind of like Erin Brockovich, and it makes the story better because nobody gives a shit if a bomb blew up 60 years ago. But if people are still suffering NOW because of this? If it’s affecting the PRESENT? Now you have a story. And that’s something I wish Time and Temperature had hit on more. Because in the end, your story always has to deal with the now. Even the great The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo (the book), about a 50 year old missing girl case, ended its story here, in the now, with its main characters in trouble.

All in all, Time and Temperature was a strange read. The story doesn’t get started (Dale first finds out about the cancer) until page 38. Before that, I had no idea where it was going. All we needed were a few scenes to establish that Dale was unhappy and unappreciated at his job, and we could’ve headed off to the Air Force Base. Instead, we have way too many scenes at work covering the same thing and then him going up to a Giants game where an earthquake occurs (which he reports on). And while it was a good scene, it had me scratching my head. Why are we here? Where is this script going?

This is something we’re told over and over again but we writers are so freaking stubborn, we continue to ignore it. We fall in love with our scenes so much that we will add 5 pages of prep, 8 pages for the scene, and 5 pages of transition back to the original story JUST SO WE CAN GET THAT SCENE IN. That’s 18 pages you just wrote so you could get a single scene in. No wonder this script clocks in at 120 pages. Screenwriting is about eliminating anything that doesn’t keep the story moving forward. A trip to a Giants game moved this sideways.

But once we got to the actual investigation, the script picked up. And I started to understand Santora’s vision better. He was going for something different, a little quirkier than your average investigation story. For example, in one scene, when he’s rushing to interview a top Air Force general, Dale forgets his bag of clothes. Which is really bad because he’s still dressed in a Santa Clause suit from a just-finished news bit. I can already imagine the shot of that interview in the trailer.

Then there’s another scenario where he rendezvous with a mysterious figure in an abandoned parking lot. It’s very film noir. Unfortunately, it was Dale’s turn with the baby that day, so he’s actually wearing a baby bjorn, with a baby in it. “Is that a… baby bjorn?” the shadowy figures asks. The scene ends on the perfect note too, when the man, Peters, warns him about what’s coming…

The Black List loves this kind of stuff, where you’re riding the line between drama and humor. If you want to end up on the list, an unpredictable balance between these two will help.

Santora also does a good job with our hero, Dale. I think it’s always important to give your characters a “thing.” It doesn’t have to be a flaw, but there should be something specific that defines them. Dale is defined as “the person everyone forgets.” That point is hit on over and over again. And it’s the reason Dale’s so driven. He wants to be remembered for something. When you don’t define your characters with that specific trait, that’s when you’ll get the note from readers: “I never got a sense of that character.”

This just happened to me in a consult script I was reading. The main character was defined, but the three other family members were not, and it was very frustrating because despite each of them having a lot of screen time, I had to profess to the writer that I didn’t really know any of them.

Anyway, Time and Temperature was an up and down experience that was more good than bad. If Santora has some directing talent, he very well could turn this into a movie to watch for. It has just enough of a unique voice to distinguish it from all the other stuff out there.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned 1: Hurt other people with your hero’s actions, making it tougher for your hero to keep going. Dale’s Dad informs Dale that because of his snooping around the base, he’s about to be kicked out of his home. Now Dale’s decision to move forward is much tougher, as it’s not just hurting himself. It’s hurting someone he loves.

What I learned 2: Screen time does not define characters for an audience. You can’t just put a character in a movie for 70 minutes and assume that because they’re in it for so long, the audience will just “get” them. It’s up to you to clarify who your character is to the audience. Santora must’ve hit on the fact that Nick was a forgotten man a dozen times (when he walked into a library he was in the day before, the librarian couldn’t remember his face). So decide what that thing is that defines your character and then hit on it repeatedly through action and dialogue.

All this week, I’ll be putting one of YOUR dialogue scenes up against a pro’s. My job, and your job as readers of Scriptshadow, is to figure out why the dialogue in the pro scenes works better. The ultimate goal, this week, is to learn as much about dialogue as we can. It’s such a tricky skill to master and hopefully these exercises can help demystify it. Here’s yesterday’s “You vs. Pro” if you haven’t read it yet.

In this opening scene, which takes place 50 years in the future, SAM FREEMAN, a “memory diver,” is preparing to go inside the brain of a comatose soldier to try and save him. The soldier’s father, ADMIRAL BLOCK, and Sam’s boss at the hospital, TRENT HARKNESS, head into the operating theater with him.

SAM, admiral BLOCK, and HARKNESS enter the operating theater. Block’s son HARRISON is already hooked up to the Rig.

SAM: Listen, Admiral… I think, given your son’s prognosis, speaking as his therapist… I don’t want you to get your hopes up, ok.

BLOCK: What the hell are you saying? He’s my son!

HARKNESS: No no no, what Dr. Freeman is saying, sir, with this kind of procedure-

SAM: What I’m saying is that maybe it’s time to let go. Do the decent thing, let your kid fade out. Lord knows he could use some peace.

Harkness, mouth agape. Block, turning fire engine red.

BLOCK: You may want to think carefully about the next words that are going to come out of your mouth.

SAM: Or maybe you want to think about what you’re signing your son up for. The years of therapy. The pharmacy’s worth of drugs to get him even remotely close to stable. The drain he’ll be on his family, financially and emotionally. He’ll know. Oh, he’ll know. And he’ll hate every minute of it.

Harkness is turning white as a sheet. Complete shock.

SAM (CONT’D): That’s what you want for him, I won’t stop you. But maybe you should think on whether death isn’t kinder than your selfish need to prolong a life that’s already over.

Block, teeth bared, GRABS Sam. PUSHES him against the wall.

BLOCK: You…

Harkness snaps out of it. Frantically calls for some orderlies to pry Block off Sam.

SAM: Go ahead, get it out. Let loose. Come on. Do it.

Block, muscles taut with fury. We realize Sam genuinely wants Block to beat the shit out of him. And after a couple of tense seconds, Block sees it, too.

BLOCK: You’d like that, wouldn’t you?

He releases his grip. The ORDERLIES burst in, ready to regulate. Block holds up his hands; the orderlies hang back.

BLOCK (CONT’D): You don’t know my son. You don’t know shit. (to the orderlies)

It’s okay, I’m good.

HARKNESS: I’m terribly sorry, Admiral. I assure you, Dr. Freeman will-

But Block’s not paying attention to Harkness. He stands next to his son, strapped into the Rig.

BLOCK: When he was seven, Harrison brought home a stray dog. Mr. Tails. Ugly mutt. Kid loved that damn thing.

Block runs a hand through his comatose son’s hair.

BLOCK (CONT’D): One day, they’re out playing, dog gets hit by a car. I see the animal’s in pain, dying. Try to explain to Harrison what’s the humane thing to do.

Block fixes Sam with a hard stare.

BLOCK (CONT’D): Wouldn’t let me near the dog. Kept kicking me. Punching. Kid’s seven, and he’s putting up one hell of a fight. Knew he’d get his ass whooped, too. Didn’t care. Just needed me to take his damn dog to the vet. Wouldn’t back down.

There’s a stillness in the room, punctuated only by the sound of biomonitors beeping in the background.

BLOCK (CONT’D): I know my son. I know what he’d want me to do. If there’s even the smallest chance…

A silent understanding passes between the two men. Finally, Sam nods.

SAM: I’m sorry for what I said. It wasn’t my place.

BLOCK: You said what you thought you had to. No harm in that. But next time you suggest euthanasia to a parent, I recommend you keep your trap shut.

Sam clicks his cyberdeck into the Rig. Removes the dust plug from the datajack in his skull.

Harkness is staring daggers at Sam. This isn’t over. As he lies down and reaches for the data cable:

SAM: So what happened to Mr. Tails?

Block’s eyes cloud over.

BLOCK: You got work to do, doc.

SAM: Yeah. I suppose I do.

Sam jacks in. His eyes close.

RIG OPERATING SYSTEM (V.O.) Begin playback: March 18, 2057.

Loading memory…

FADE TO WHITE.

In this next scene, a father, Matt, is preparing his daughters, 17 year old Alexandra and 10 year old Scottie (yes, Scottie is a girl), to have their last moment with their mother, who’s been in a coma and has just now been taken off life support. Matt is particularly concerned about Scottie, who’s been slow to grasp the magnitude of her mom’s situation.

[Elizabeth] now lies with no machines at all. Around her BALLOONS droop, FLOWERS wilt, get-well CARDS lie in a pile. Elizabeth too is wilting and drooping. Her skin is pasty, and her cheeks are hollow.

SCOTTIE: How come Mom isn’t on any more machines? Is she getting better?

The adults exchange glances. Dr. Herman approaches Scottie.

DR. HERMAN: You must be Scottie. (off her nod –) Scottie, I have a present for you.

Dr. Herman hands her a little squeaky RUBBER OCTOPUS she pulls from her pocket.

DR. HERMAN (CONT’D): That’s right. It’s an octopus. Such a funny creature with its eight legs. But did you know octopi are actually extremely intelligent, like dogs and cats? They have unique personalities, and just like us they have a lot of defense mechanisms. I’m sure you know about the ink sac. She uses ink to confuse her predators. She can camouflage herself. She can emit poison, and some can mimic more dangerous creatures, like the eel. I keep her to remind me of our defense mechanisms — our ink, our camouflage, our poison, all the things we use to keep away hurt. The reason Dr. Johnston invited me here today is to meet you, Scottie. I’ve heard a lot about you.

SCOTTIE: Like what?

DR. HERMAN: I’ve heard that you’re a wonderful and unique and spirited girl.

Dr. Herman shoots a look at Matt before continuing.

DR. HERMAN (CONT’D): And I’ve heard your mom’s not doing too well and that she’s going to die very soon.

All watch Scottie react to this news.

SCOTTIE: Dad, is that true?

MATT: Yes, Scottie. It’s true.

DR. HERMAN: You’re going to have to be a very brave girl right now, and you’re surrounded by people who love you. I came to meet you and tell you that if you ever want to talk about what you’re feeling, I would like to talk to you too. I can help you face what’s going on without all the silly defense mechanisms that work for an octopus but not for us.

DR. JOHNSTON: Okay. Thank you, Dr. Herman.

Dr. Herman looks at everyone with great sincerity before leaving. Scottie is left holding the octopus. She drops it, and it squeaks a little.

ALEXANDRA: What the fuck was that?

DR. JOHNSTON: Yes, well, they say she’s very good one-on-one.

SCOTTIE: So Mom’s going to die for sure?

DR. JOHNSTON: Yes. We worked really hard with her, but three other doctors and I agree she’s in what we call an irreversible coma. Do you know what that means?

SCOTTIE: It means she doesn’t have a brain anymore.

DR. JOHNSTON: Not exactly, but… yes, that’s the general idea. So we’re doing exactly what she wanted us to do if that ever happened. That’s why she’s not attached to the machines anymore.

ALEXANDRA: It’s for the best, Scottie. Look at her. She’s not happy like this.

DR. JOHNSTON: The purpose of medicine is to heal, and we can’t do that now.

MATT: Do you understand?

SCOTTIE: Yes. What will we do with her body?

Dr. Johnston looks to Matt for this one.

MATT: First Mom’s going to give some of her organs to other sick people, so she can

help save their lives. That’s a really neat thing she’s doing. Then we’re going to… we’re going to scatter her ashes in the ocean. You know how Mom always loved the ocean.

SCOTTIE: Her ashes?

Scottie looks at her mother, picturing her as ashes.

SCOTTIE (CONT’D): When will she die?

DR. JOHNSTON: Any day now, I’m afraid. But you still have some time.

Beat.

DR. JOHNSTON (CONT’D): Well. Let me know if you have any more questions.

MATT: Thanks, Sam.

The doctor leaves, and the room is quiet. Scottie is in a sort of trance.

ALEXANDRA: Come here, Scottie.

Scottie goes to her sister, who takes her in her arms.

SCOTTIE: Do eyeballs burn?

SID: Hey, Scottie. Don’t think about stuff like that.

Okay, let’s take a look at our first scene, which is from an amateur script called “Firstborn.” At the outset, the scene appears to have a lot going for it. We have clear goals (Block wants to save his son. Sam’s trying to convince Block it’s a bad idea). We have conflict (stemming directly from this difference in opinion).

We approach the scene from a slightly unique angle. You’d expect a doctor to fight for a patient’s life. In this case, Sam’s fighting to end the patient’s life. So the scene has a slightly different flavor to it. And yet, something feels off about it. The dialogue isn’t popping the way it should. Why?

Well, the first thing I noticed was that a lot of lines had what I call “hiccups,” additions or pieces of text that screw up the rhythm of the line. Take this line for example: “You may want to think carefully about the next words that are going to come out of your mouth.” The hiccup here is “that are going to.” “That are going to” shouldn’t be in this sentence. It should just be, “You may want to think carefully about the next words out of your mouth.” Reads better, right?

Or check out this line: “No harm in that. But next time you suggest euthanasia to a parent, I recommend you keep your trap shut.” This sentence doesn’t even make sense. “The next time you suggest euthanasia, keep your trap shut.” How can he keep his trap shut about euthanasia if he already suggested it? What’s meant to be said here is that the next time Sam thinks about suggesting euthanasia, he should keep his trap shut. It’s a small oversight, but a hiccup that gives the reader pause. Once these hiccups start piling up, the read becomes difficult and frustrating.

Next, there were a series of cliché/cheesy lines. Stuff like, “He’ll know. Oh, he’ll know.” The second “Oh, he’ll know,” is overly dramatic and unnecessary. Later, when Block realizes Sam wants him to beat him up (for reasons that aren’t clear to me), Block replies, “You’d like that, wouldn’t you?” How many times have we heard this line in movies and TV before? Hundreds? Thousands? Once something becomes overused, it feels lazy and cheesy.

But, of course, the worst line of all is, “When he was seven, Harrison brought home a stray dog. Mr. Tails.” Adding the dog’s name is a hiccup here. Stopping after “dog” would’ve been preferable. But the real problem is that by going back in time to tell a story, you take us out of the immediate conflict of the scene. This is why I advise to stay away from flashbacks or mono-backs (monologues focusing on backstory) if possible. It’s not that they can’t work. It’s that they rarely work.

To better understand why this dialogue doesn’t work, let’s examine why the dialogue in the second scene does work. For those who don’t recognize the scene, it’s from the film, “The Descendants,” which starred George Clooney. The script, written by Alexander Payne, Jim Rash, and Nate Faxon, won an Academy Award.

So what’s so good about this scene? Well, I’m guessing none of you picked up on this while reading it, but notice how this is the most heartbreaking scene in the script, the finally-letting-go scene, and it contains zero emotion. What I mean by that is, there’s no yelling here, no crying, no fighting. It’s a very calm matter-of-fact scene. With that in mind, ask yourself which scene is more emotionally moving to the reader, the first or the second? The second, right?

You’re going to hear it again and again on this site. Irony plays such a huge part in making the elements of a screenplay work. This is a scene about death with no emotion. That’s exactly why it works. Because it’s unexpected. It’s not the way you traditionally see the scene going down.

Speaking of untraditional, let’s take a closer look at the octopus. I think the octopus dialogue is genius, and I’ll tell you why. Imagine your version of a dying hospital scene. What’s the last thing you’d expect to be in that scene? An octopus. And that’s exactly why this works, because it’s so unexpected. It comes out of nowhere and throws this weird energy into the scene that tells the audience, “You do not know where this is going.” And when we don’t know where something is going, we pay closer attention. Because we want to see where it goes.

Contrast this with the first scene. We all knew exactly where that scene was going. There was nothing unexpected about it, which was a big reason why you probably grew bored reading it. This was a problem yesterday as well. I was never in doubt about where that amateur scene was going. And the more expected something is, the more boring it tends to be.

The octopus becomes this weird failed attempt to placate Scottie. And when it fails, the rest of the room is left to pick up the pieces, leading to yet more unexpectedness. Who’s going to clean this up? What are they going to say to clean it up? These are the questions that drive the scene, that make us want to keep reading.

Yesterday, there were those of you who saw the amateur scene as better than the pros. Do you feel the same way today? If so, why? Share your thoughts. But try to articulate WHY you think the dialogue works (or doesn’t). “The second one is better” doesn’t help anyone. It’s only once you understand why something is or isn’t working that you’re able to apply that knowledge to your own screenwriting.

What I learned 1: The octopus – In well-worn scenes that we’ve seen a thousand times before, inject your own “octopus” into the scene to make it feel different.

What I learned 2: Hiccups – Hiccups are any additional words in your dialogue that aren’t necessary. But it can also be incorrect use of words, tenses, subjects, phrases. Hiccups are just as bad as spelling errors. On their own, they’re not a big deal. But once they pile up, they can spell doom for your script.