Search Results for: the wall

Gone Girl had a disappointing final act. So Fincher had author Flynn rewrite it for the movie. Will it save the film?

Gone Girl had a disappointing final act. So Fincher had author Flynn rewrite it for the movie. Will it save the film?

In the five years since this site began, it’s hard to believe that I STILL haven’t written an article about the third act. I think it’s because the third act is kinda scary. It’s easy to set up a story. The middle act is tough, however I’ve written a couple of articles demystifying the process. But with final acts, it feels like every one is a little different. They’re sort of like their own little organisms, evolving and changing in indefinably unique ways, packed with previously established variables that are constantly fighting against one another, and it’s hard to bring all of that together in a streamlined package.

Blake Snyder does a really good job breaking down the third act, and his methods are a good place to start, but what I’ve found is that his approach mostly applies to comedies and romantic comedies, where the audience is aware of the exaggerated structure of the moment (hero loses the girl, is at his lowest point) but doesn’t mind. They come to see these movies because they like laughing and seeing the guy get the girl, so they don’t need some genius plot point to keep them invested.

With that said, I think it’s a good idea to have a baseline approach to your third act. It’s the same thing as if you’re building a house. You want to get the blueprints in order. But you still need to keep the option open of adding a breakfast nook over here, or moving the kitchen over to the other side of the main room. So here’s how a prototypical third act should be structured. It doesn’t mean that your act should be structured the same way. It just means it’s a starting point.

THE GOAL

Without question, your third act is going to be a billion times easier to write if your main character is pursuing a goal, preferably since the beginning of the film. “John McClane must save his wife from terrorists” makes for a much easier-to-write ending than “John McClane tries to figure out his life” because we, the writer, know exactly how to construct the finale. John McClane is either going to save his wife or he’s going to fail to save his wife. Either way, we have an ending. What’s the ending for “John McClane tries to figure out his life?” It’s hard to know because that scenario is so open-ended. The less clear your main character’s objective (goal) is in the story, the harder it will be to write a third act. Because how do you resolve something if it’s unclear what your hero is trying to resolve?

THE LOWEST POINT

To write a third act, you have to know where your main character is when he goes into the act. While this isn’t a hard and fast rule, typically, putting your hero at his lowest point at the end of act two is a great place to segue into the third act. In other words, it should appear at this point in the story that your main character has FAILED AT HIS/HER GOAL (Once Sandra Bullock gets to the Chinese module in GRAVITY, that’s it. Air is running out. She doesn’t understand the system. There are no other options). Either that, or something really devastating should shake your hero (i.e. his best friend and mentor dies – Obi-Wan in Star Wars). The point is, it should feel like things are really really down. When you do this, the audience responds with, “Oh no! But this can’t be. I don’t want our hero to give up. They have to keep trying. Keep trying, hero!” Which is exactly where you want them!

REGROUP

The beginning of the third act (anywhere from 1-4 scenes) becomes the “Regroup” phase. This phase often has to deal with your hero’s flaw, which is why it works so well in comedies or romantic comedies, where flaws are so dominant . If your hero is selfish, he might reflect on all the people he was selfish to, apologize, and move forward. But if this is an action film, it might simply mean talking through the terrible “lowest point” thing that just happened (Luke discussing the death of Obi-Wan with Han) and then getting back to it. Your hero was just at the lowest point in his/her life. Obviously, he needs a couple of scenes to regroup.

THE PLAN

Assuming we’re still talking about a hero with a goal, now that they’ve regrouped, they tend to have that “realization” where they’re going to give this goal one last shot. This, of course, necessitates a plan. We see this in romantic comedies all the time, where the main character plans some elaborate surprise for the girl, or figures out a way to crash the big party or big wedding. In action films, it’s a little more technical. The character has to come up with a plan to save the girl, or take down the villain, or both. In The Matrix, Neo needs to save Morpheus. He tells Trinity the plan, they go outfit themselves with guns from the Matrix White-Verse, and they go in there to get Morpheus.

THE CLIMAX SCENE

This should be the most important scene in your entire script. It’s where the hero takes on the bad guy or tries to get the girl back. You should try and make this scene big and original. Give us a take on it that we’ve never seen in movies before. Will that be hard? Of course. But if you’re rehashing your CLIMAX SCENE of all scenes?? The biggest and most important scene in the entire screenplay? You might as well give up screenwriting right now. If there is any scene you need to challenge yourself on, that you need to ask, “Is this the best I can possibly do for this scene?” and honestly answer yes? This is that scene!

THE LOWER THAN LOWEST POINT

During the climax scene, there should be one last moment where it looks like your hero has failed, that the villain has defeated him (or the girl says no to him). Let’s be real. What you’re really doing here is you’re fucking with your audience. You’re making them go, “Nooooooo! But I thought they were going to get together!” This is a GOOD THING. You want to fuck with your audience in the final act. Make them think their hero has failed. I mean, Neo actually DIES in the final battle in The Matrix. He dies! So yeah, you can go really low with this “true lowest point.” If the final battle or confrontational or “get-the-girl” moment is too easy for our hero, we’ll be bored. We want to see him have to work for it. That’s what makes it so rewarding when he finally succeeds!

FLAWS

Remember that in addition to all this external stuff that’s going on in the third act (getting the girl, killing the bad guy, stopping the asteroid from hitting earth), your protagonist should be dealing with something on an internal level as well. A character battling their biggest flaw on the biggest stage is usually what pulls audiences and readers in on an emotional level, so it’s highly advisable that you do this. Of course, this means establishing the flaw all the way back in Act 1. If you’ve done that, then try to tie the big external goal into your character’s internal flaw. So Neo’s flaw is that he doesn’t believe in himself. The only way he’ll be able to defeat the villain, then, is to achieve this belief. Sandra Bullock’s flaw in Gravity is that she doesn’t have the true will to live ever since her daughter died. She must find that will in the Chinese shuttle module if she’s going to survive. If you do this really well, you can have your main character overcome his flaw, but fail at his objective, and still leave the audience happy (Rocky).

PAYOFFS

Remember that the third act should be Payoff Haven. You should set up a half a dozen things ahead of time that should all get some payin’ off here in the finale. The best payoffs are wrapped into that final climactic scene. I mean who doesn’t sh*t their pants when Warden Norton (Shawshank spoiler) takes down that poster from the wall in Andy Dufresne’s cell? But really, the entire third act should be about payoffs, since almost by definition, your first two acts are setups.

OBSTACLES AND CONFLICT

A mistake a lot of beginner writers make is they make the third act too easy for their heroes. The third act should be LOADED with obstacles and conflict, things getting in the way of your hero achieving his/her goal. Maybe they get caught (Raiders), maybe they die (The Matrix), maybe the shuttle module sinks when it finally gets back to earth and your heroine is in danger of drowning (Gravity). The closer you get to the climax, the thicker you should lay on the obstacles, and then when the climactic scene comes, make it REALLY REALLY hard on them. Make them have to earn it!

NON-TRADITIONAL THIRD ACTS (CHARACTER PIECES)

So what happens if you don’t have that clear goal for your third act? Chances are, you’re writing a character piece. While this could probably benefit from an entire article of its own, basically, character pieces still have goals that must be met, they’re just either unknown to the hero or relationship-related. Character pieces are first and foremost about characters overcoming their flaws. So if your hero is selfish, your final act should be built around a high-stakes scenario where that flaw will be challenged. Also, character piece third acts are about resolving relationship issues. If two characters have a complicated past stemming from some problem they both haven’t been able to get over, the final act should have them face this issue once and for all. Often times, these two areas will overlap. In other words, maybe the issue these two characters have always had is that he’s always put his own needs over the needs of the family. The final climactic scene then, has him deciding whether to go off to some huge opportunity or stay here and takes care of the family. The scenario then resolves the character flaw and the relationship problem in one fell swoop! (note: Preferably, you are doing this in goal-oriented movies as well)

While that’s certainly not everything, it’s most of what you need to know. But I admit, while all of this stuff is fun to talk about in a vacuum, it becomes a lot trickier when you’re trying to apply it to your own screenplay. That’s because, as I stated at the beginning, each script is unique. Indiana Jones is tied up for the big climax of Raiders. That’s such a weird third act choice. In Back To The Future, George McFly’s flaw is way more important than our hero, Marty McFly’s, flaw. When is the “lowest point before the third act” in Star Wars? Is it when they’re in the Trash Compactor about to be turned into Star Wars peanut butter? Or is at after they escape the Death Star? I think that’s debatable. John McClane never formulates a plan to take on Hanz in the climax. He just ends up there. The point is, when you get into your third act, you have to be flexible. Use the above as a guide, but don’t follow it exactly. A lot of times, what makes a third act memorable is its imperfections, because it’s its imperfections that make it unpredictable. If you have any third act tips of your own, please leave them in the comments section. Wouldn’t mind learning a few more things about this challenging act myself!

So I’m peering out at the specscape this diddly-do and it’s not looking so volcanic . “Diddly-do” is code for “day” by the way. “Specscape” is code for “spec landscape.” And I have no idea what volcanic means. Actually, before I continue, you should know that I quit sugar cold-turkey recently. And you have to realize, I was a sugar addict. It’s now Day 7 and my intelligence has gone waaaaaay down as a result. Like miles below sea level. I know it was already underwater to begin with, but that’s still low. I’m still going to write this blog post though because I’m feeling passionate about something. Quentin Tarantino when he talks about NO HARD EIGHT FOR YOU-type passionate!

Where was I? Right, so there have really only been 2 “true” spec sales this year (one about Greek Gods in modern day. Another about an astronaut trying to survive a hobbled spacecraft) and I’m thinking that’s not enough, man. True, lazy-ass Hollywood really didn’t get started until January 6th (you can’t put January 1st on a Wednesday and expect people to go balls to the wall for two days, go back to a relaxed weekend, then start up again – of course they’re going to wait until the 6th), but 17 days and only two spec sales isn’t enough. Especially with everyone geeked up to find the first great script of 2014. We should have had 5 or 6 big spec sales already.

Now some might say that Hollywood isn’t a spec-sale town anymore. And that’s true to a certain degree. It ain’t the 90s. These days it’s more about finding writers with potential, sending them to meetings everywhere in town, and hoping they book some assignments. But I think Hollywood is always ready to buy something if it’s good. And therein lies the problem. Nobody’s been writing anything good!

Remember back in the day when Terry Rossio and Ted Elliott used to write all those awesome screenwriting articles on their website? And we’d visit that site every week because they were guaranteed to give us something new to think about? There’s one article I remember quite well, though the title of it escapes me. It was basically about the fact that when you’re writing a screenplay, each page you’re writing needs to be worth a million dollars. Because that’s how much they’re going to spend on the budget of the film (110 pages, 1 million per page, 110 million dollar budget). So the question they posed was, “What makes your writing worth a million dollars a page?”

I never forgot that. And sure, there’s an argument to be made that that’s the most unhealthy approach to creating art ever. But I don’t agree. Thinking in those terms can actually help you become a better writer. Because all it’s doing is it’s making you justify your choices and your effort.

And they need to be justified, because the stakes have gone WAY up since that article. These days, the budgets for major studio films START at a hundred million, and can go up to THREE-HUNDRED MILLION. Add marketing and distribution costs for not just America, but dozens of countries around the world, and we could be talking a 600 million dollar investment before a single person buys a ticket.

With the average screenplay being 110 pages, that equals out to almost SIX MILLION DOLLARS PER PAGE.

Welcome to the new state of movies. So do you believe your script is worth 6 million dollars per page? That’s a pretty intimidating question right? You can see why these studios lean so heavily towards intellectual property. That’s their answer to the question, “Why are our in-house scripts worth 6 million dollars a page?” Because Batman has proven to be a beloved bankable hero for 70 years. Because millions of people have read and loved The Hunger Games and they’ll come out to see a movie-version of the book.

But yeah, that six million dollar a page figure is a little scary. So let’s dial it back and be more realistic. Most big-time studio movies have around a 200 million dollar budget, which means each one of your pages needs to justify 2 million dollars spent. Do you believe each one of your pages justify that kind of investment?

That’s a really complicated question but here’s an interesting way to look at it. Can someone open your script to any page, read it, and say, “That page is worth 2 million dollars?” I don’t know. I mean not all pages are created equal. Some you need to have context to understand. Some are naturally more exciting than others.

Ah, but I’ll tell you this. Anyone can definitely open a script to a random page and say, with certainty, “That’s not worth 2 million dollars.” And I believe that’s the secret to writing a “2 million dollar a page” screenplay. Your job is simply to make sure that people can’t open your script to any page and be able to tell right away that it isn’t worth 2 million bucks. All that page needs to be is good enough so that that person can’t definitively say it isn’t. To know for sure, they have to read on. And if you’ve done your job, after reading the next page, they’ll want to read the next one, and then the next one after that and the next one after that until they get to the end. You’ve written a 2-million dollar a page screenplay if someone who picks it up CAN’T PUT IT DOWN until they finish. That is the ONLY surefire way to know if you’ve written something that a studio will invest 200 million dollars in.

Here’s the root of the problem for why we’re not seeing enough of these types of screenplays. Writers aren’t trying hard enough. I mean assuming you know the basics – how to come up with a marketable fresh premise, how to create a complex interesting main character, how to keep your narrative moving, how to structure your script – it’s up to you to give us 100%.

Want to know how to write 110 2-million dollar pages? Start with the scene. There are 50-60 scenes in every script. I want you to answer this next question honestly. Don’t bullshit yourself or me. That latest script you’ve been pushing to everyone, trying to get everyone to read? How many of those 60 scenes can you say you gave 100% on? That each and every scene in that script is as good as you can possibly make it?

If you can HONESTLY tell me that all 60 of your scenes are as good as you can do? That’s great. I am virtually making sweet love to you right now. But if that’s not the case, all I can ask is, “Why?” What in the world makes you believe you can put a script out there where you haven’t made each scene as good as it can be?

Let me let you in on a secret. From the amateur spec scripts I read (and I read about 10-15 a week), do you know how many scenes in those scripts I’d say, on average, are the best the writer could’ve done? Maybe around 5. 5 scenes in each script! For more seasoned writers, I’d say maybe 20-25. Which seems better, but it’s still less than HALF of what you need to write something great!

If you want to SELL something – if you REALLY want to play with the big boys – why are you holding yourself to that shit-ass standard? Why not, when you put your script in someone’s hand, be able to say “I did as well as I possibly could’ve done here?”

The one huge advantage amateur writers have over pros is THEY HAVE NO DEADLINE. A studio isn’t all up in their e-mail box asking where the new draft is. You’re free to spend AS MUCH TIME as you want on your script, to perfect it beyond perfection, so you have no excuse not to make it great.

And if you follow that model, each page WILL be worth 2 million dollars because every page in every scene is going to have a purpose. It’s going to be there for a reason. And you’ll have added the necessary conflict or suspense or dramatic irony or plot twist or side-splitting dialogue that was necessary to make that scene great.

Look, I can’t promise you if you do this, you’re going to sell a screenplay. Because the truth is, a lot of writers don’t yet know how to write a script, how to pick a concept, how to arc a character, etc. But if you hold yourself to this standard NOW, when you’re still learning? Then by the time you DO understand all this stuff, and your skill level matches your craft, you’ll have the kind of discipline that’s going to give you a HUGE advantage over everyone else.

So get to it. Open your latest script up and make it 2-million-bucks-a-page worthy!

So tonight American Idol had its season premiere (go J. Lo!) and I have a pretty good idea of what your response to that is. Who the f— cares! That show had its heyday a decade ago. It doesn’t have any influence in the music industry anymore. There’s 10 million other singing shows competing against it, depleting the talent pool and dimming the luster of anyone who wins the competition. Who gives a crap, right?

I’ll tell you who gives a crap. ME. Now you’re probably wondering why someone obsessed with screenwriting would give a rat’s melody about a reality show highlighting a bunch of caterwauling Katy Perry wannabes. Well, it’s the same thing that drew me to screenwriting in the first place. The idea of going from a nobody to a somebody. Just like how if you sing something amazing in front of the world, you become an instant superstar, if you write a great screenplay and the right person reads it, you can sell it for a million bucks. It’s one of the coolest things about this business.

Ah, but that’s not the real reason I’m obsessed with American Idol. No no no. I’m obsessed with it for a much darker reason. I watch it because the auditions so closely resemble the amateur audition process in screenwriting. Every time someone comes up to sing, it’s the same as when a script lands in an executive’s lap. This is their chance. This is their shot to prove to the world they’ve got it.

The big difference is that when you sing, it’s all out there for everyone to hear. Within seconds you know if the person’s good or not. With writing, the process is a little more complicated. It takes a few pages to figure out if the person’s got it. And if they don’t, the writer doesn’t get that direct feedback a singer does. They’re left in the cold, forced to interpret things through a quick e-mail or no reply at all. It’s one of the reasons writing is so tough. It’s difficult to get any quality feedback on your work.

But the thing that gets me so infatuated with Idol, is that the process for determining who’s got it in singing and who’s got it in writing is the same. It all comes down to the voice! Think about any singer you’ve fallen in love with. Think about your favorite singer right now. What first drew you to them? It was something different and unique about their voice, right? Maybe it’s the tone. Maybe it’s the pitch. Maybe it’s the way they emphasize certain phrases or play with certain chords. But mostly it’s something in their voice you hadn’t heard from any other artist before. From Eminem to Louis Armstrong to Adele to Lorde. You would never mix them up with any other artist, right?

And that’s the key phrase: “SOMETHING YOU HAVEN’T HEARD BEFORE.”

I would love it every aspiring screenwriter would equate their writing to singing and ask themselves that question: “What is it about my voice that’s different?” What can I do with my voice that’s unlike any other voice out there? Because here’s the thing I see on American Idol. There are a TON of singers that are “good.” They’ve trained most of their lives. They’ve taken lessons. They’ve practiced their asses off. So when they sing, you nod your head and you say, “That was pretty good.”

But “that was pretty good” is the kiss of death. Nobody pays for “that was pretty good.” Nobody goes to a concert for “that was pretty good.” Nobody’s going to tell their friends about “That was pretty good.” You know it when you see these guys on American Idol. They’re forgettable. They’re aping artists we’re already heard and because they’ll never be as good as those artists, why would anyone want to hear them?

Aspiring screenwriters don’t seem to realize this for some reason. That they’re no different from these singers. They’ve done the training. They’ve read the books. They’ve written a bunch of screenplays. And still they’re getting no traction and they don’t know why. The reason is because they’re the writing equivalent of these guys going up for that audition in front of J. Lo, Keith Urban, and Harry Connick Jr., that are “pretty good.”

Being the screenwriting-obsessed megalomaniac that I am, whenever I see these singers on Idol, year after year, I ask myself, “What can a writer do to make sure he isn’t the equivalent of that guy?” And the answer is: you gotta sound like the dudes/gals who are unique! You gotta establish your own voice! Just like that unique tone you hear in your favorite artist, you have to find that tone in yourself, that unique combination of prose, humor, subject matter, theme, dialogue, rhythm that makes your scripts sound like nobody else’s out there.

In order to make this analogy work, you kind of have to imagine walking in front of three judges and having them read your script out loud, then judging you. Would they read through the first five pages and think, “You know what? I’ve never heard something quite like this before?” Or would they say, “You know what? I’ve seen over a hundred movies with this exact same scene in them?” “I’ve read a hundred writers that write just like this?” Yesterday is a perfect example. Wes Anderson’s script, “My Best Friend.” If I read that out loud, myself and two other judges would remember it. It’s different. What’s different about you!?

You can apply this across all competitions. If you were a chef, what kind of dish would you make that’s unlike any other dish out there? You could make something as simple as mashed potatoes. But if you added a certain spice or a hint of some fruit or vegetable, that dish could go from ordinary to unforgettable. And that’s what you have with a screenplay. You literally have millions of ingredients to play with. So you don’t have an excuse for not trying to be different in some way.

Or, to make a more relevant comparison, think about your favorite directors. Go look at this trailer for Divergent. Quite possibly the most generic execution of a sci-fi film ever, right? Now look at this one. How much more memorable is that? If you were an executive and these two clips popped up in your e-mail, which director would you call back? It’s all about voice. It’s about somebody putting their unique interpretation on the direction of the film. That’s what you’re trying to do with a script – offer your own unique interpretation.

Maybe the best example of voice is this short movie I saw the other day. I will guarantee, 100%, that after you watch this movie, you will never ever forget it. Ever. Go ahead, watch it and tell me differently.

SOLIPSIST from Andrew Thomas Huang on Vimeo.

Unforgettable right? A unique voice, right? That’s what you want to do. You want to make it impossible for people to forget about you.

Okay, so to reiterate, what is it, not just in your current screenplay, but in ALL of your work, that makes you different? That makes your screenplays read differently than everything else out there? And I’m not saying it has to be like that short – 100% balls to the wall weird. It can be subtle. But it has to be SOMETHING. Or else you’re one of the thousands of people who get up on that stage in front of those judges for their big moment, and give a technically fine but ultimately forgettable performance. Identify that thing that’s unique in you (you might need to ask someone who knows you well to do this) and find a way to infuse that into your scripts. Remember, the worst thing you can be in art is forgettable. So please don’t let that be you.

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

Happy reading!

TITLE: Hunter’s Moon

GENRE: Action/Adventure

PREMISE: “Loosely based on a feature article I penned for Maxim (“The Death Dealer”) some years ago about an ex-merc who takes wealthy hunters on human safaris – mostly in Africa where they hunt poachers.”

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: “The merc this story is based on – a very twisted individual by the name of Keith Idema – died last year in Mexico. He made the cover of the Wall Street Journal for detaining Afghan civilians – and torturing them! – back when bin Laden was still alive, trying to get intel on where he was hiding. Idema – who owned a gun store near where I grew up – taught me to shoot. On the weekends, he used to go to El Salvador to fight alongside the Contras against the Sandinistas.My first year of college (U of Maryland) – I came back from a long weekend and he was in my apartment, hiding behind the couch which he had flipped over to guard against grenade attacks.

Yes, you read that right. Here’s his Wikipedia page:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jonathan_Idema

The script, which I’d pitch as Billionaire Boys Club meets Most Dangerous Game meets Deliverance is pretty fuckin’ cool and based on events that actually took place.

TITLE: Penalty

GENRE: Black comedy

LOGLINE: An ambitious soccer referee works his way up the lower leagues when he’s suddenly bribed to start throwing games.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: “One thing I notice about your amateur submissions are that they seem to be mostly written by under 30s with comparatively little life experience. Technically they might be structured well and are always written in a confident style but generally lack a certain nuance that only age can give you. So come on Carson, how about us oldies. I propose an over 40s week to see if you can encourage a more measured kind of voice that can harness the important ground rules to something truly life-affirming.”

TITLE: Safeguard

GENRE: Action Thriller

LOGLINE: A hitman is offered the chance to avenge his wife’s murder by joining forces with a team of highly skilled ex-cons to prevent an assassination attempt in Paris. It’s Ronin meets the Dirty Dozen…

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: “SAFEGUARD was a 2013 Nicholl SF. The script was a (four week) first draft so as you can imagine, I was utterly stunned to see it advance as far as it did in the contest. My first script was an honorable mention in Trackingb and also a PAGE Award winner and has since been taken on by the guys behind the Batman Trilogy and Man Of Steel.”

TITLE: Rigged

GENRE: Biopic

LOGLINE: The true story of Bobby Riggs, The Battle of the Sexes, and how the mafia may have influenced the most famous tennis match in history.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: “Rigged combines something you love (tennis) with something you hate (biopics). Like chocolate covered raisins. It’s also tailor-made for an A-list actor (Paul Giamatti?), has clear GSU and features some of the most intense tennis scenes this side of Bridesmaids. Is this the first amateur biopic to get a “Worth the Read” by Carson?”

Genre: Sci-fi

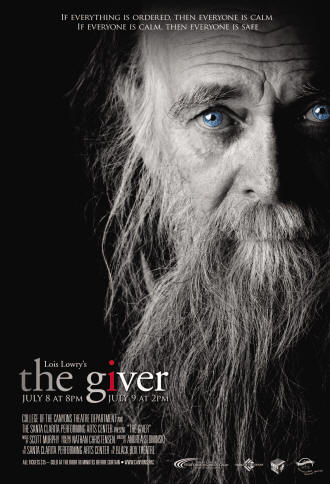

Premise: In the far off future, humans live in a “utopia” where there is no hate, no fear, no sadness, and most prominently, no knowledge of human kind’s history. When a young boy discovers the shocking truth about that history, he knows he must escape the community.

About: The Giver was a book published back in 1993 and quickly broke out as one of the most popular dystopian novels ever written. It eventually made its way onto school reading lists. The adaptation I’m reviewing was written back in 2004 by Todd Alcott, who wrote the animated movie, Antz. However, since then, the script has obviously been rewritten a few times, and is now credited to Michael Mitnick (who looks freakishly like Ferris Bueller. Look him up!). I believe the film is almost done shooting, and has a fancy cast that includes Alexander Skarsgard, Meryl Streep, Taylor Swift, Jeff Bridges, and Katie Holmes. The film comes out in August of next year. “Salt” director Phillip Noyce directed.

Writer: Todd Alcott (based on the book by Lois Lowry)

Details: 118 pages – 12-14-04 (listed as “final” draft)

So after hearing 3 separate people over the past year tell me that The Giver was a great script (and 2 OTHER people tell me it was one of their favorite books growing up), I finally decided to take a whack at it (get it? “take?” Cause like, it’s called “The Giver?” Mm-hmm, good right?)

Truth be told, it’s the old “bad title bug” that keep me from chomping on this piece of script celery. The Giver?? It sounds like a depressing Western where a Silas Marner like character, homeless and half-clothed, offers kind favors to passerbys. Ugh, shrug, no thanks Doug. I want to read something called GOOD scripts. GOOOOO-OOOOO-OOOO-DDDD. Good scripts.

Shows you how important a title is. The wrong one makes readers run like Panama Canal workers from mosquitos. Of course, this WAS a novel adaptation, so they were kind of stuck with what they were given (get it? Because “The Giver” and then I just said… oh forget it). But if you’re writing a sci-fi spec, make sure you title it something a little more sci-fi sounding.

So is The Giver as good as the praise it’s been given? Or am I going to GIVE it a failing grade? Only one way to find out. Join me in my Scriptshadow time machine so we can travel faaaar off into the future, into the world of… The Giver.

Jonas is a 12 year old boy who’s a little brighter than the rest of the kids. More astute, I’d say. Jonas lives in a future town of 3500 people, and boy is this town rad. First of all, no cars! That’s because there are no streets. Everyone rides around on bicycles and wears trendy clothes and enjoys each other’s company and seems genuinely happy with life.

There are some negatives. Nobody ever questions anything. Nobody’s allowed to go outside the town. Nobody’s allowed to lie. And there’s hardly any color in this world. It’s like everything is muted. Oh, and your job is chosen for you.

That’s right. In fact, as the story begins, a ceremony is coming up where all the 12 year olds (12 is the last year of childhood in this community) will be told what they’re doing for the rest of their lives. So they all go, and out of the 50 twelve year-olds, Jonas watches patiently as his friends go one by one and get jobs like “fisherman” and “helping the elderly” and “director of recreation.” But when it’s Jonas’s turn… he’s PASSED OVER.

This draws a concerned muttering from the crowd and naturally, Jonas is freaked out. Finally, after all the twelves have been designated, Jonas is called up. His job will be “The Receiver Of Memory,” a job that is only given once in a blue moon. And it appears to be bad. Because Jonas’s family is FREAKING OUT.

Jonas heads home, but now everybody treats him like he has West Nile Virus (I don’t know what my obsession with mosquito-transmitted diseases is in this review – honest). Nobody’s too fond of this Receiver of Memory crap. Even his parents look at him weird. So the next day, Jonas meets with the current Receiver of Memory, an old man whose job it is to pass on all the memories of the world’s history before he dies (he’s our “Giver”). You see, the Receiver of Memory is the only one who knows what human kind’s past really was.

And so he begins telling Jonas about cars and sleds and Paris, as well as violence and murder and wars. Jonas learns it all. He’s both horrified and fascinated. But it’s when he learns about death – specifically the way in which death is secretly administered in the community – that he really changes. This is not a place Jonas wants to grow up. Which is why he decides to get out. But will he make it before they find out his plan? And what will happen if they stop him? What will be Jonas’s fate?

You know, I’m starting to understand the appeal of adapting these young adult novels to film. They’re relatively breezy in terms of plot and concept, making them ideal for the limited space that is a movie script. The more “adult” novels tend to be complex and heavy, and when you have a lot of layers (a lot of complexity), that’s hard to fit into 120 pages.

I will say I’m getting a teensy bit worried about all these dystopian movies hitting the circuit, though. When you read enough of them, they all start to blend together. But The Giver is good. What I liked about it was how it established its world. From the number of people (3500) to the geography (the town’s boundaries are laid out nicely) to the way people dress, to the way people learn, to the way people work – I got a great sense of this community right away. And that’s something I rarely see in amateur sci-fi scripts, where the worlds and boundaries all feel like they were conceived during an early morning Denny’s breakfast after a night of drinking (“Yo dude, check it out. What if everyone, like, has a third ear??” “Yeah man! But then, ironically, they’re all deaf.” “Yeah!!! Brilliant dude! Hey stewardess! Another round of pancakes! Future millionaires in the house!”)

I loved the way the opening act built. This is something I don’t talk about much, but you want your story to always build. You want to feel like everything’s getting bigger, heavier, more complex and harder. I read too many scripts where we just stay at that flat level the whole way through, and when you do that, the read gets boring.

It started with this mysterious community, continued with Jonas seeing strange things the other kids couldn’t see, and moved on to a mysterious old man who would watch Jonas at school. We then get the shock of him not being picked at the ceremony. The reveal of his unique job. How that job changes the way the town perceives him. The mystery of earth’s history. The mystery of what happened to the previous Receiver of Memories. And it just kept going from there. It never slowed down.

All this reminded me of the importance of the mystery box. I know some of you guys hate JJ and his mystery box. But it really works when it’s done well. And here, it’s used perfectly. This thread of “What happened to the last Receiver?” is powerful enough (we wonder, if it happened to the one before, will it happen to our hero? And a script is always more exciting when you think your main character may be in danger) to keep the pages turning. It’s a prime story engine.

Having said that, I moist sointantly have some questions. Let me ask you guys something? Would you want to live in blissful ignorance in The Matrix? Or would you like to be released and live in the “real world?” Because when I saw what the “real world” was like in those Matrix sequels, I wanted to stay in the damn Matrix! I am perfectly fine living in a pretend world if I don’t know it’s pretend. Sign me up.

And with The Giver, I kept asking the same question. Is this community that bad? I mean, everyone seems to get along. Everyone’s happy. People don’t ask questions about things but that’s because everyone knows they’ve got it good. I mean there’s no war. No hate. No fighting.

So what is it, exactly, that we’re running away from in The Giver? Free will? Choice? I mean, yeah, those things are important, obviously. But The Giver makes too good of an argument for its utopian community. Everybody is really freaking happy. I can count the people in my life who are happy on one hand! So I ask it again: What’s so bad about this society here?

Now yes, (spoiler) there is a baby killing scene. I am not for killing babies. But can’t Jonas focus on maybe amending that little policy rather than run away? He’d do a lot more good. And you know what The Giver was missing? A villain. It needed a big fat villain because we needed someone to represent the corruption of the system, someone who used it for his own gain. We needed EVIL. Like I said, beside baby-killing moment, there really wasn’t anything that bad about this place.

Of course, just the fact that The Giver is making me think about all this stuff is great. It’s breaking that elusive “5th Wall” (the 5th Wall is the wall that makes the reader actually place themselves in your story and ask what they’d do). And once you have your reader doing that, you’re golden, baby. You’re screenplay golden.

So yeah, this script is good. It just has a few anomalies here and there. I’m eager to find out what they changed in the shooting draft. Id’ be shocked if they didn’t add a bigger villain. I’ll definitely see this when it comes out.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You want your story to build. That includes, but is not limited to a) throwing bigger and bigger obstacles at your hero over the course of the script, b) a number of revelations/surprises that also increase in importance as the script goes on, and c) upping the stakes as the script goes on. The stakes for your hero on page 90 should be much higher than they were on page 45, which should be much higher than they were on page 10.