Today’s movie is a prime example of the power of a small group of people working together to create art.

Genre: Sci-Fi

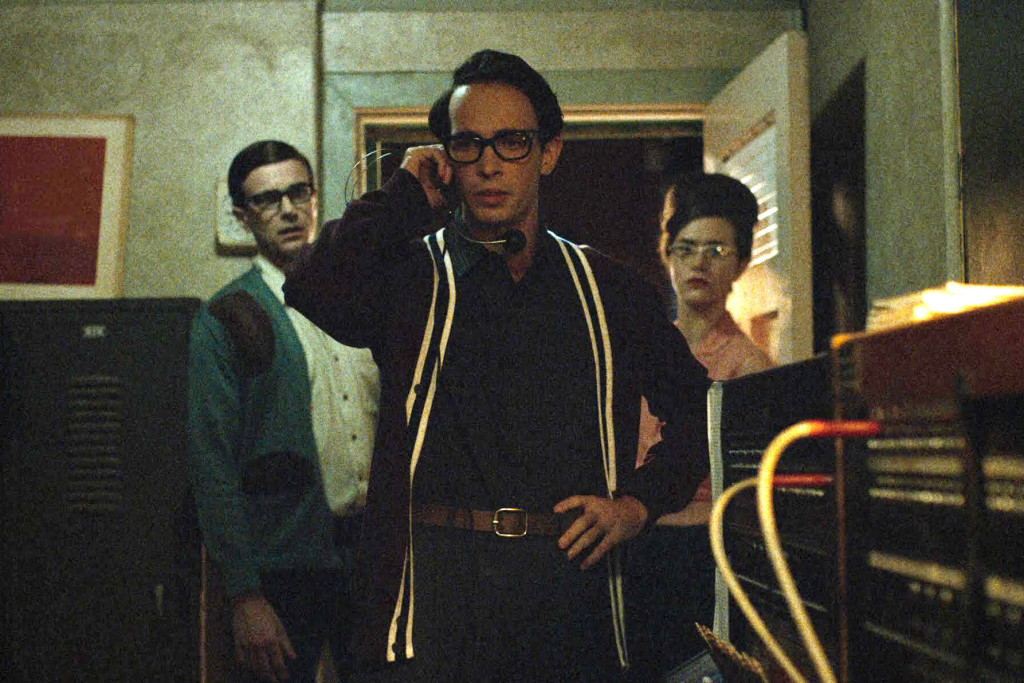

Premise: Set in the 1950s, a DJ and a switchboard operator living in a small town hear a strange noise coming over the airwaves and spend the night trying to decipher what the noise is and where it’s coming from.

About: The Vast of Night was a tiny film created by a small group of passionate people which would eventually get accepted into Slamdance and become one of the breakout films at the festival. Amazon would purchase it and when the movie debuted this weekend, it held a surprising 93% Rotten Tomato score, a virtually unheard of achievement for a film made by and starring people who have zero footprint in the movie business. This is director Andrew Patterson’s first film. It is writers James Montague and Craig Sanger’s first film. You’ve never seen the two leads before. So what was it about the movie that got people so revved up? Let’s find out!

Writers: James Montague and Craig W. Sanger

Details: 90 minutes

I’m all about the UFOs. Aliens visiting this planet is my jam. But it’s well-traveled Hollywood real estate and therefore you have to come with a fresh angle to stand out. The Vast of Night is one of the few movies in this genre to actually achieve this.

The story takes place in Small Town, USA during the evening of a big high school basketball game. We meet Everett Sloan, our DJ helping people at the gym set up for the game. Everett’s trying out his new audio tape recorder and having a blast interviewing people about the game.

Everett runs into Fay Crocker, a geeky female switchboard operator with a penchant for science who begins rattling off some of the crazy predictions she’s read about the future in her Popular Mechanics magazine collection. We follow the two around the school and into the quiet small town until they eventually split up to do their jobs, him to DJ and her to work the switchboard.

The Vast of Night then places us in a single profile shot watching Fay do her job for FIFTEEN FULL MINUTES. During the tail end of this session, she hears a strange noise and calls Everett to patch him in to see if he knows what it is. Everett doesn’t but wants to play it on the air to see if anybody else knows.

This leads to an older army veteran, Billy, calling in, who says he has a story to share and goes on about how he, too, heard that noise when he was deployed. After Billy’s call, an older woman, Mabel, calls in and says she needs Everett to come to her house so she can tell him something important about the noise. Everett grabs his tape recorder and Fay and they head over there. Mabel says that her own daughter was taken by aliens responsible for that noise.

Figuring that the aliens must be nearby and will probably leave once the basketball game is over, Everett and Fay grab a car and drive into the vast of night to try and locate the alien ship. They eventually do. But when the alien ship spots them, will it allow them to go back to town? Or will it make sure the story ends here?

I give the writers credit for keeping the narrative tight. That’s a little screenwriting trick you can use with plots that don’t have a lot of sex appeal. The nature of limiting the timeline to 2 hours or 3 hours or 4 hours, gives the story a false sense of urgency that tricks the viewer into feeling like the plot is moving along faster than it is.

But the real star here is the directing.

These guys had no money yet they found a way to make this feel like a movie. By the way, that’s one of the primary things producers and studios look for in directors. They’re looking for people who can make a 1 million dollar movie look like a 5 million dollar movie. Heck, Robert Rodriquez built an entire brand on that.

But back to Vast. The first thing they did was set the story in 1953 which added some production value you don’t get from your run-of-the-mill UFOs-in-the-sky movie. And they set it at night because the director couldn’t hide the telltale signs of this not being a 1950s town in the day. So that was a smart move.

He then told the story in a series of long single shots. Which is really hard to do. Especially when you have inexperienced actors. These actors are being asked to remember 10 pages of dialogue while doing complex walking one-take shots. Which is exactly why you don’t usually see that. Other directors (I’m talking indie directors, not Sam Mendes with 100 million dollars to play with) are too scared to try it. If you ruin one of those shots, you’re setting up for another 3 hours to get the next one. And there’s only so many of those takes that you get on a tiny budget like this. Yet that was the risk the director took in order to make sure his movie felt different from everyone else’s.

The director, Patterson, would also mix in these insane dolly shots. There’s one shot in the middle of the movie that pulls out of Everett’s DJ station and zooms along the ground, like a skateboarding possum on meth, through the entire town, going into the school, all in a single shot, mind you, then INTO THE BASKETBALL GAME ITSELF as its going on, goes onto the court while the game is playing, then swishes back out of the school and over to Fay in her switchboard room.

You just don’t see that in your average indie. It’s ambitious.

But the directing can’t outrun the writing issues in Vast. The primary issue is a lack of stakes. What Vast of Night attempts to do is use IMPLIED STAKES. Implied stakes are when you vaguely imply that good things might happen if the hero succeeds or bad things might happen if the hero fails.

Implied stakes don’t work well. You need CLEAR STAKES. Clear stakes are, “You better get the money by 6pm or we’re going to kill you.” Implied stakes are, “You better get the money or else.” Vast of Night is an implied stakes screenplay. We’re not sure why figuring out this sound matters other than it’s going to quench Everett and Fay’s curiosity. Is quenching curiosity “stakes?” Not where I come from.

And then you have an inevitable ending, which is unfortunate. There are so many risks in the direction and the ending is something we figure out two minutes after the strange noise appears. I mean, what else can you do really? You’re building up to this UFO. Obviously you’re going to show it. (spoilers) And since you need to add some extra pop, you’re probably going to have your leads beamed up to the ship. And that’s exactly what happens.

On the plus side, the dialogue is occasionally fun. I enjoyed Fay’s fascination with the future in the opening walk. And Billy’s call-in to the station was a highlight. The best performance of the movie comes from a character who never appears on screen. And while it’s easy to focus on his performance, Montague and Sanger gave him some juicy dialogue to work with.

In the end, this is a case of young fresh talent making a movie. There were always going to be missteps. But the pros overwhelm the cons when it’s all said and done. The Vast of Night is worth checking out.

[ ] What the hell did I just stream?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Today’s what I learned is on you guys. I watched Space Force this weekend, which was awful. But I couldn’t figure out why it was awful. It’s not a bad idea. When I think Steve Carrel and Space Force, I imagine funny stuff. And I love 75% of the cast. Yet nothing in the show works. And it’s hard to figure out why other than to say it’s just not funny. So for those of you who saw it, educate me. What can I learn from Space Force on how not to write a comedy TV show?

Due to the corona-virus craziness, the Scriptshadow segue to producing has been pushed back a few months. And guess who benefits from that? YOU GUYS. I’m extending The Last Great Screenplay Contest deadline to July 4th. That’s right. INDEPENDENCE DAY. Think of it this way. On that day, your screenplay will finally achieve independence from you. Of course, it will now depend on me. But that’s another story.

NEW CONTEST DEADLINE: SATURDAY, JULY 4TH, 11:59 PM PACIFIC TIME

If you don’t know anything about The Last Great Screenplay Contest or how to enter, go here!

As for this weekend, I’m hearing good things about this new sci-fi movie debuting on Amazon Prime called, “The Vast of the Night.” So I’m going to check that out. Also, the long-awaited Steve Carrel show, “Space Force,” debuts on Netflix at midnight. So I’ll at least check out the first episode of that this weekend. Expect me to review one of the two Monday.

Hope everyone has a great weekend. Get some writing done!

So I finished Netflix’s Into the Night and I can honestly say it’s the best TV show of the year so far.

I haven’t encountered a show with this level of urgency in a long time. The closest I can think of is Netflix’s Black Summer. But what makes Into the Night so much better is that the urgency is organically built into the premise. They have to keep flying to avoid daylight.

There are three screenwriting tips I want to bring up in particular with this show. It should go without saying that I’m including spoilers. Watch the show first if possible. I guarantee that once you start, you won’t be able to stop.

Oh, and fun little piece of trivia. This show is based on a book. And the creator adapted the entire first season from the FIRST PAGE of the book.

The first concept I want to talk about is called sandwiching.

There comes multiple times in every TV or Feature script (but TV especially) where you’ve got to write a scene with boring exposition or two characters who don’t have a lot going on. This could be the C-story in a TV episode. You’ve been told you have to write the scene and there’s nothing interesting going on between the two characters.

In these situations, you want to SANDWICH the scene with something really big before and PROMISE something big is going to happen after. If you do this well, we’ll tolerate the scene.

So there’s this moment in episode 5 of Into the Night where Sylvie, our helicopter pilot protagonist, goes back to the apartment of her dead boyfriend and mourns. Another character shows up to try and convince her to come back.

Now before this scene, we just showed a major fight between two characters in another location where one character beats the other one to near death. He then leaves that character to get back to the plane. That’s the first piece of bread on this sandwich.

The second piece is we have to leave within an hour! That’s when the sun comes up. So we have to get back to the freaking airplane NOW! This is our exciting second piece of bread which is a PROMISE that something interesting is coming. And it’s for that reason we tolerate this slow decent-but-mostly-boring scene of Sylvie trying to get over her dead boyfriend.

Where writers get into trouble is when they get lazy, when they stop sandwiching boring scenes, when they try to pile 3 or 4 boring scenes inside a sandwich, or when they don’t understand the technique at all. Because that’s when you’re at risk of writing 20-30 pages of boring story.

In an ideal world, every scene would be riveting. But it’s just not possible. You need to set certain things up for later scenarios to be exciting. And setup can be boring.

Moving on, tip 2. Dialogue doesn’t matter as much as you think it does. Into the Night is one of the most riveting TV shows I’ve ever seen. But it’s in another language. And I don’t understand that language.

Therefore, I have to use subtitles. Now, for those who don’t know about the job of subtitling, these people do not directly translate what the characters are saying. Instead, they give the bare bones generalized idea of what they’re saying in its most basic form.

If you want to have some fun, turn on the dubbed English audio and also put on English subtitles. You’ll see that their dubbed words don’t even match the subtitles. That’s because two different people are doing those jobs and they’re both just putting up their generic interpretation of what’s being said.

I bring this up because everybody talks about the importance of dialogue when shows like Into the Night and movies like Parasite are amazing yet we’re basically watching them with 3rd grade level English dialogue translation.

Does this mean you shouldn’t strive to write great dialogue? Of course not. But it’s a reminder that it’s what’s SURROUNDING the dialogue that’s most important. If you get that right, a scene will work regardless of how basic the dialogue is. Shows like Into the Night prove that.

Add conflict. Add tension. Add dramatic irony. Come up with an interesting scenario, like 7 passengers questioning an 8th passenger on if he’s really who he says he is.

From there, do the best you can with your dialogue. But it’s setting up the situation surrounding the dialogue that matters most.

Finally, one of the writing devices I like the best is when the writer makes it seem TRULY IMPOSSIBLE that the characters are going to succeed in the end.

And I stress “truly” for a reason. Because most writers set up an ending where they’re already thinking of how they’re going to get the characters around the obstacles in their way, and therefore, it doesn’t TRULY feel impossible. We can sense the writer carving that escape hatch that the characters are going to find and be okay.

Instead, you want to write your ending almost like you hate yourself. You want to make it as hard as possible for you the writer to figure out how your characters are going to get out of this.

Into the Night aces this test and then some.

(Major Spoilers)

While on their final flight – they’re not going to have fuel after this – the group has located an old Soviet bunker in Bulgaria that government officials are fleeing to. So their plan is to land the plane at the Bulgarian airport and haul ass to the bunker.

Now get this.

There’s no guarantee they’re going to get inside. It might be locked. It might be full. So right from the start, it’s bad news.

Next, they don’t know exactly where the bunker is. They’re working with some janky old map.

When they land, they have half an hour until sunrise. So they have to find a mystery bunker that they only vaguely know the location of in a country they’ve never been to before, driving on roads that are completely foreign to them, and then hope they get inside when they get there.

Only one person can carry the map but there are 9 people so they have to split up into two jeeps. So the first jeep is speeding away. The second jeep has to try and keep up with them on these winding roads. If they lose them, there’s no way to know which way to go.

Three quarters of the way there, the second jeep crashes. So they have to walk the rest of the way. Meanwhile, the first jeep crosses a gate that automatically closes behind them, locking the second group out.

The second group eventually gets to the gate but it’s electric, so they can’t even climb over it. There’s only 12 minutes left before the sun rises, by the way. They don’t even know if they’re close to the bunker or not. Also, nobody knows where the bunker entrance is. It’s not like a McDonald’s with Golden Arches signaling the location. It’s metal doors built into a hill.

I was sitting there watching this both in awe of the show, in how well it was crafted, and in awe of the writer, who so boldly made things difficult for himself.

Because it would’ve been easy to throw one mildly difficult obstacle at the characters. To throw THIS many obstacles requires a lot more work. Because now you’re stopping the characters more. You’re having to come up with solutions to these problems you’ve created. And bad writers don’t want to do that. It takes way longer to write the obstacle overcoming scenes and requires a lot more brainpower.

So I was rooting for both the characters and the writers simultaneously with this ending because I couldn’t have asked for a better end to this season.

Those are my Into the Night tips. Take them with you, into the night, and use them on your next screenplay!

This screenplay battle regarding the movie, “Yesterday,” has become an international story. Today, I review the original draft that led to the drama!

Genre: Drama/Fantasy

Premise: When a struggling musician realizes that he’s the only person on the planet to remember the Beatles, he starts passing the band’s songs off as his own. Only, they don’t create the stir he expected.

About: Jack Barth was a 62 year old screenwriter who had been trying to get his scripts made for over 20 years. The dream finally happened when Richard Curtis heard his pitch for a Beatles-inspired concept about a singer who wakes up one day as the only person on the planet who remembers the Beatles. Curtis supposedly (this is where the story gets murky depending on who you talk to) refused to read the script and went off to write his own version of the idea. Long story short, Curtis took the big writing credit, Barth got stuck with the smaller “Story By” credit, despite the fact that the two screenplays are [supposedly] very similar. Now Barth is taking his argument to the streets because he wants it known who really wrote this movie. You can read more about it here in this Uproxx article. Today, I’ll be reviewing Barth’s original screenplay, the one that would eventually become “Yesterday.” His script is called “Cover Version.”

Writer: Jack Barth

Details: 103 pages, Version 10b 01 July 2016 (posted by Jack Barth on Twitter)

There’s a romanticization about the “unmade” draft of a script. That was one of the reasons I was inspired to create Scriptshadow. I wanted to read all of those famous unused drafts that were so much better than the movies that made it to the big screen.

But what I found was that, 99% of the time, it was b.s. It certainly made for a good story – these unused genius screenplays. But they were always worse than the finished product. And most of the time, a lot worse. The best of these unused scripts were simply different. Same general story. Different choices. But none of them were genius.

That’s because, as fun as it is to claim, “The studio ignored a genius script to make an AWFUL film,” the reality is, it’s in the studio’s best interest to make the best movie they can. So given the choice between a good and bad draft, they almost always pick the good one.

If you disagree with this, show me the receipts. Name the movie that was terrible and the genius script that they overlooked.

Sure, there’s stuff like Source Code. I’m notorious for how much I loved that script. But even though I didn’t love Duncan Jones’ interpretation, I’m not going to sit here and tell you it was that different from the screenplay.

And, to be honest, I’m not even sure that’s what I’m looking for today. It seems like Barth is more interested in getting the credit he deserves for “Yesterday,” instead of being treated like this second hand leper who was only good enough to come up with the idea. I’ve always loved this concept so I’m curious to see what he did with it. Let’s take a look.

The year is 2016. Dan, the lead singer of Clay Enema, is in his 30s. His band mates, girlfriend Ella, Cesar, and Sykes, still enjoy jamming and getting the occasional gig. But the future isn’t looking good. It seems that no matter what Dan does, Clay Enema can’t breakthrough.

Then one day, Dan walks into a rehearsal and, to get warmed up, strums a few chords of the Beatles’ song, “Yesterday.” Curious, Ella comes over and asks him what the song is. He plays along. “Ha ha. Just something I’ve been working on.” Cool, she says, let’s try it out. He laughs her off and gets down to business. He’s got this new song he’s positive will be a hit and he wants to practice. But the band keeps telling him, no, we want to play that other song you were working on.

Naturally, he thinks they’re messing with him so the whole thing turns into a fight and he storms off. But there was something about their conviction that they’d never heard the song before that piques Dan’s curiosity. So he looks online. And he goes to the record store. And he checks his CD collection. There is no mention of the Beatles ANYWHERE!

So Dan apologizes, gets the band back together and starts teaching them all these “new songs” he’s been inspired to write. And what do you know, they start booking more gigs.

People like the songs. But to Dan’s dismay, they don’t LOVE the songs. And so the band’s success stalls. They become big enough to go on small tours and make a living. But not globs-of-fans-darting-across-streets-crying-just-to-get-a-look-at-them big.

Dan doesn’t get it. These are the greatest recorded songs in HISTORY. Why isn’t Clay Enema as big as the Beatles? Dan’s dismay eventually leads to the group breaking up and Dan trying to build a Beatles replica band, complete with the 60s costumes and haircuts. But it doesn’t work.

Eventually, Dan comes to the realization that if there was never a Beatle, John Lennon wouldn’t have been assassinated. So he goes on a quest to find the never famous Lennon, who it turns out is a fisherman, and Dan confides to Lennon what he’s done. Lennon, who just may believe him, tells him that the reason the songs aren’t hits is because Dan didn’t write them. They’re not true to who he is and therefore they can never be hits. Dan thanks him, ditches the Beatles catalog, and starts writing his own songs again. The end.

So there are two questions being asked here.

1) Which version is better?

2) Did Curtis “steal” from Barth’s script despite the fact that he claims to have never read it?

I’ll deal with the first question first. Of the two versions, I think Yesterday was better. But not by much. Basically, Curtis asked the question, “What kind of movie does the audience want to see?” Whereas Barth asked the question, “What would *actually* happen here?”

Both avenues are interesting. There’s a dramatic irony sledgehammer with Curtis’s version whereby we know that the Beatles songs are amazing. So we revel in this opportunity to witness someone bring those songs into the world for the first time. We WANT his success. We WANT to see everybody scream and go crazy over this guy. Because we’re in on the secret. And it’s an extremely exciting secret to be a part of. Who doesn’t want to watch audiences experience “Here Comes the Sun” for the first time?

Barth’s version is more grounded and realistic. It asks the question, can you separate the music from the artist? Is the artist so intrinsically connected to the songs that become massive hits that they’re a package deal? You can’t split them up.

While I think that’s an interesting question, it leads to a much more subdued experience. And my experience with movies is that they don’t work well with middling, with average, with subdued. Movies work best with extremes, especially when you’ve got a big idea. John McClane isn’t running around some two-story insurance building in downtown Lincoln, Nebraska. He’s running around a brand new state of the art skyscraper in Los Angeles.

So while I respect that Cover Version is more realistic, it didn’t give me that big whirlwind celebrity experience that Curtis’s version did.

With that said, Barth’s version is still good. Because it is more realistic, it has a clearer theme, which is that your art has to come from you. It can’t come from someone else.

Now when it comes to the second question, things become fuzzier. And as it’s been a year since I’ve seen Yesterday, I don’t remember all the details. But the two things I’m seeing people bring up online about Cover Version that prove Curtis read Barth’s script despite claiming not to have, is the John Lennon thing and the Harry Potter thing.

I can tell you right now that neither of these moments convince me that Curtis read Barth’s script. And I consider myself somewhat of an expert in this area because I’ve heard tens of thousands of pitches. And I’ve read thousands of screenplays, many of which cover similar ideas. What I’ve found is that writers choose similar characters and ideas more than they realize. That’s because we’re all fishing from the same well. The same media cycle. The same shows. The same movies. The same pop culture. So most writers think similarly. (Screenwriter Pro Tip: When making any major decisions in your script, ask yourself, “Would another writer think of this?” If you think maybe they would, come up with something else!)

I would be willing to bet that if you gave 10 screenwriters this idea, 7 of them would’ve come up with the John Lennon scene. And I say that because it’s kind of obvious. Any good writer would naturally realize that if there was no Beatles, John Lennon never gets assassinated. Which means he’s alive. And if you have John Lennon alive, you put him in the movie.

I’d also assume most writers would make that a poignant important scene late in the film like both writers here did. Where things get fuzzy is that, if I remember correctly, John Lennon in Yesterday did some job by the sea? And here, in Cover Version, he’s a fisherman. So that’s a legitimate gripe. You could argue that that’s not a coincidence. Still, I don’t know. It’s definitely not a smoking gun situation.

And then with the Harry Potter joke at the end, that’s another thing that a lot of writers would come up with. If nobody remembers the Beatles, theoretically, maybe there are a few other famous British celebrities that never happened, which would be fun to make a joke about. And who’s more well known in the UK than Harry Potter? So that joke doesn’t convince me of anything.

Look, the reality of the situation is that these things are never black and white. I could see a situation where Curtis had someone cover Barth’s script for him and give him the broad strokes of Cover Version so he could make sure he wasn’t copying the major plot points. You’d think this would happen if only for legal reasons. Maybe a couple of those ideas from the coverage seeped into Curtis’s script. Who knows?

But the truth is, these are very different screenplays. One of them asks, what happens when you become famous off another person’s songs and the other asks, what happens when you have the greatest music catalogue in history and you still can’t achieve success? Once the script diverges from that initial hook, it’s two different stories.

And look, a lot of people get screwed over with their breakthrough script. The deal is the bigger name gets the credit and the smaller name now gets a seat at the table. This is how it’s been for many many people who’ve broken into Hollywood. The complicating factor here is that Jack Barth isn’t some 23 year old wunderkind. He was a 62 year old man who’d been grinding away at his craft for two decades and credit matters more to someone in that situation. So it sucks he didn’t get it.

This leads to a bigger discussion where I don’t understand why someone like Curtis, who’s insanely successful – even if he did write a story that was 90% different from Barth’s – why not just give Barth equal credit? He needs it so much more than you do. That’s the only part that bothers me. Do you really need any more residual checks? Is one more Porsche a year going to make you that much happier? What the hell happened to compassion and selflessness?

Anyway, Cover Version is a good script. And, more importantly, it’s a great idea. Writers can spend YEARS looking for an idea like this. And most never find one. So Barth gets credit for the most important thing of all in this case, which is that he conceived of a kick-ass movie idea.

Script link: Cover Version

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Draw out your hook for as long as possible. One thing Barth did better than Curtis was that when it got to the hook point of the movie – Dan realizing that nobody on the planet knows about the Beatles other than him – Barth really drew it out. From when Dan first strums Yesterday to his band to a few days later where he tests out their first Beatles song together. I was bothered in “Yesterday” by how quickly we whipped through that section because, remember, the hook is why the audience is there. That’s what they’re most excited to see. They want that moment where the hero is playing the Beatles song to the people who have never heard of the The Beatles before. So give them what they want. Draw that moment out for as long as you can. No audience member is going to be mad at you for it.

Genre: Comedy/Horror

Premise: (from Black List) Twenty years after a failed exorcism, a meek young woman becomes unlikely friends with the foul-mouthed demon that possessed her as a child.

About: This one’s got a couple of big pillars holding it up. Buzzy indie production house A24 and none other than JJ’s Bad Robot. Megan Amran, who broke into the business a decade ago writing material for the Academy Awards, has written on The Simpsons, Parks and Recreation, and The Good Place. This is her first feature script to break through.

Writer: Megan Amram

Details: 100 pages

Just a reminder for those who don’t read Scriptshadow often.

The possession genre is the biggest bang-for-your-buck genre out there. Possession movies are obscenely cheap to make. Since you don’t traditionally need special effects, you can shoot them on the same budget you’d shoot a drama. Keep the locations limited and you can even keep it under a million. Even if the thing only has a five million dollar opening weekend, you’ve made a profitable movie.

BUT!

But you have to find a fresh angle. If you’re the 3824th writer to conceive of “The Exorcism of [Insert Female Name Here],” don’t expect your script to garner much attention.

Megan Amram takes that advice as far as someone can take it. Today we have a gross-out vulgar exorcism comedy. The 40 Year Old Virgin as an exorcism flick? Mixed with some Seth Rogen humor? Is that a thing? I guess we’re about to find out.

When she’s 10 years old, Kennedy gets possessed by a real mean demon named Lamashtu, who is one of the worst demons you can get possessed by. Think The Exorcism times ten. She’s really bad.

Kennedy’s mom, Karen, does everything in her power to exorcise Lamashtu, calling on all the best priests in the area. But they’re all terrified of Lamashtu and run away. Finally, Karen realizes that good old steady yoga breathing and positive thoughts can keep Lamashtu at bay. As long as you don’t get angry, she tells her daughter, you’ll be fine.

Cut to twenty years later. The reclusive nerdy Kennedy works as a coder at a Google wannabe company. Everyone overlooks Kennedy because she’s just so… well… NICE. And nice people get stepped on. Nice people get taken advantage of.

But after Kennedy gets passed over for a promotion, Lamashtu has had enough and reemerges! Lamashtu (as Kennedy) starts screaming at everyone at work, and all of a sudden, people don’t just respect Kennedy. They like her! This girl has spunk.

Kennedy realizes that she’s made a mistake by repressing Lamashtu all these years. It’s time to fully embrace her demon instead! Even her sexist office crush, David, asks her out, leading to Kennedy’s first ever sexual experience. The event is so overwhelming that Lamashtu takes over, giving David the best sex of his life, leading to him being obsessed with Kennedy.

But when Kennedy’s evil side starts affecting her one genuine friendship with her fellow reclusive coder, she begins to wonder if the juice is worth the squeeze. Will Kennedy say F-it and become Lamashtu forever? Or is there a way to be nice again and still enjoy her life?

Man.

This was a wild one.

I’ll give Amram props on a couple of fronts. This is a fun idea. What if you stopped holding in all those things you really wanted to say and just let go? Embrace that anger you’ve always repressed. It’s one of the more fun comedic premises I’ve come across.

And Amram doesn’t neuter Kennedy’s inner demon. This is not the safe cute version of this concept. Lamasthtu regularly unloads lines like, “You want dirty talk? I’m gonna rip your big fat cock through your stomach up through your mouth til you choke on it.” Full steam ahead on the vulgarity.

The script also does one of the most important things a script must do – IT DELIVERS ON THE PROMISE OF ITS PREMISE. You get exactly what the logline tells you you’re going to get. I can’t endorse this enough. I read a lot of scripts that promise a great premise but then the script becomes something else in its second half. Or it changes genres in the final act.

No! Whatever your unique element, whatever the “strange attractor” is in your story, that’s what you want to exploit. Milk that thing until there’s no more milk left in it.

The script did have some weaknesses though. Kennedy’s job felt totally made up. It was a tech company but it was never clear what the company did (or what she did). She was just a generic “coder” and we were supposed to go with it.

I’ve said this once, I’ll say it a million times. As human beings, half our lives are dedicated to our jobs. We spend 8-10 hours a day doing them. They are often the most influential part of our lives. So if you don’t know what a character does? If you don’t know where they work, what their position is, what their everyday tasks are? You don’t truly know that character. And, believe me, we the audience can feel it.

Even if you pick a generic job, like accounting or middle management, LEARN what that company does and why your character ended up doing that job. Cause if you don’t know that, you’re not giving us the full dimension of your character. You’re only giving us the part that you care about. And it’s making the character one-dimensional.

Speaking of one-dimensional, today’s script continues a recent trend of writers treating all their male characters as moronic sexist a-holes. I don’t know when this started or why writers do it. Isn’t the male species more varied than every single one of them being moronic and sexist and an a-hole? I would hope there are some who are nice. That are cool. That are complex and interesting. And yet in 2020, finding a cool masculine male character who’s intelligent and respectful is like looking for Bigfoot.

The crazy thing is it wasn’t that long ago when I was telling male writers who used to write one-dimensional female characters, “You know that women are going to read this script, right? Do you think it’s a good idea that all your male characters are complex and well thought out and all your female characters are one-dimensional and sex objects? Do you think that’s going to go over well?”

And now it’s the exact opposite problem. Female writers are writing all their male characters as simplistic sexist idiots. You know that men are going to read your script right? Do you think that’s going to go over well?

I’m not sure where I come out on Repossession. Sometimes I thought it was funny. But other times it got too vulgar or too off-track (it didn’t make any sense for the hero to be a virgin – that felt like a whole different movie).

I think if the script stripped away the stuff that wasn’t directly related to the concept of a young woman finally allowing her anger to come out, this could be that rare comedy movie that gets released in theaters. Because the concept itself is so marketable. But it hasn’t found its legs yet. And for that reason, it wasn’t for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Here is the opening slugline for Repossession:

EXT. WEEKS FOOTBRIDGE – CRISP AUTUMN DAY

Is this okay? Traditionally, in a slugline, you only want to tell us if we’re inside or outside (INT. or EXT.), the location that we’re at (the Weeks Footbridge) and then whether it’s day or night. Amram has added “Crisp Autumn” to the slugline, which would drive purists crazy. But I think it’s perfectly fine. I like anything that gives me a clearer visual for what I’m looking at. Sure, Amram could’ve told us it was a crisp autumn day in the description underneath the slugline. But doing it here frees up the description for her to give us other information. I wouldn’t go crazy with this hack. If your additional text stretches the slugline to two lines, that’s a no-no. But if you can quickly get some relevant description in there without it feeling too imposing, there’s no harm in that.