Search Results for: F word

What’s the easiest way to tell the difference between an amateur and a pro script? That’s easy: CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT. The pros know how to do it. Amateurs don’t. Most amateurs don’t even attempt to add character development. And the ones who do usually use something like addiction or the death of a loved one to add depth. It’s not that you can’t or shouldn’t add these traits. But if you really want to delve into your character and make him/her three-dimensional, you want to give them a flaw, then have them battle that flaw during their journey, only to overcome it in the end. This is called a “transformation,” or an “arc.” It’s when your character starts in a negative place and finishes in a positive place. If you really want to boil it down and get rid of the fancy-schmancy screenwriting terms, it’s called “change.” And the best movies have central characters who go through a big change.

Now I don’t have 50 hours to write about character development so I can’t get too detailed here. But I should tell you a few things before I get to the meat of the article. Character flaws are more prominent in some genres than others. For example, you should ALWAYS include a character flaw in a comedy. Our inability to overcome our flaws is essentially what leads to all the laughs in the genre. Action movies, on the other hand, often have heroes who don’t change. The story moves too fast to explore the characters in a meaningful way. Thrillers are similar in that respect, although a good thriller will find a way to squeeze in a character flaw (I remember that movie “Phone Booth” with Colin Farrel and how it dealt with a selfish character). With horror, it depends on what kind of horror you’re writing. If you’re writing a slasher flick, character flaws aren’t necessary. A thinking-person’s horror film, though? Yeah, you want a flaw (the lead’s flaw in The Orphange was that she coudln’t move on with her life – she was obsessed with the past). In dramas, you definitely want flaws. Westerns as well. Period pieces, usually.

In my own PERSONAL opinion, you can and should ALWAYS give your characters flaws, no matter what the genre. People are just more interesting when they’re battling something internally. Without a flaw, without something holding them back, characters don’t have to struggle to achieve their goal. And that’s boring! Think about it. I always tell you to place obstacles in front of your hero so that it’s difficult for them to achieve their goal. Well what if while your character’s battling all these EXTERNAL obstacles, he also has to battle a huge INTERNAL obstacle?? Much more interesting, right??

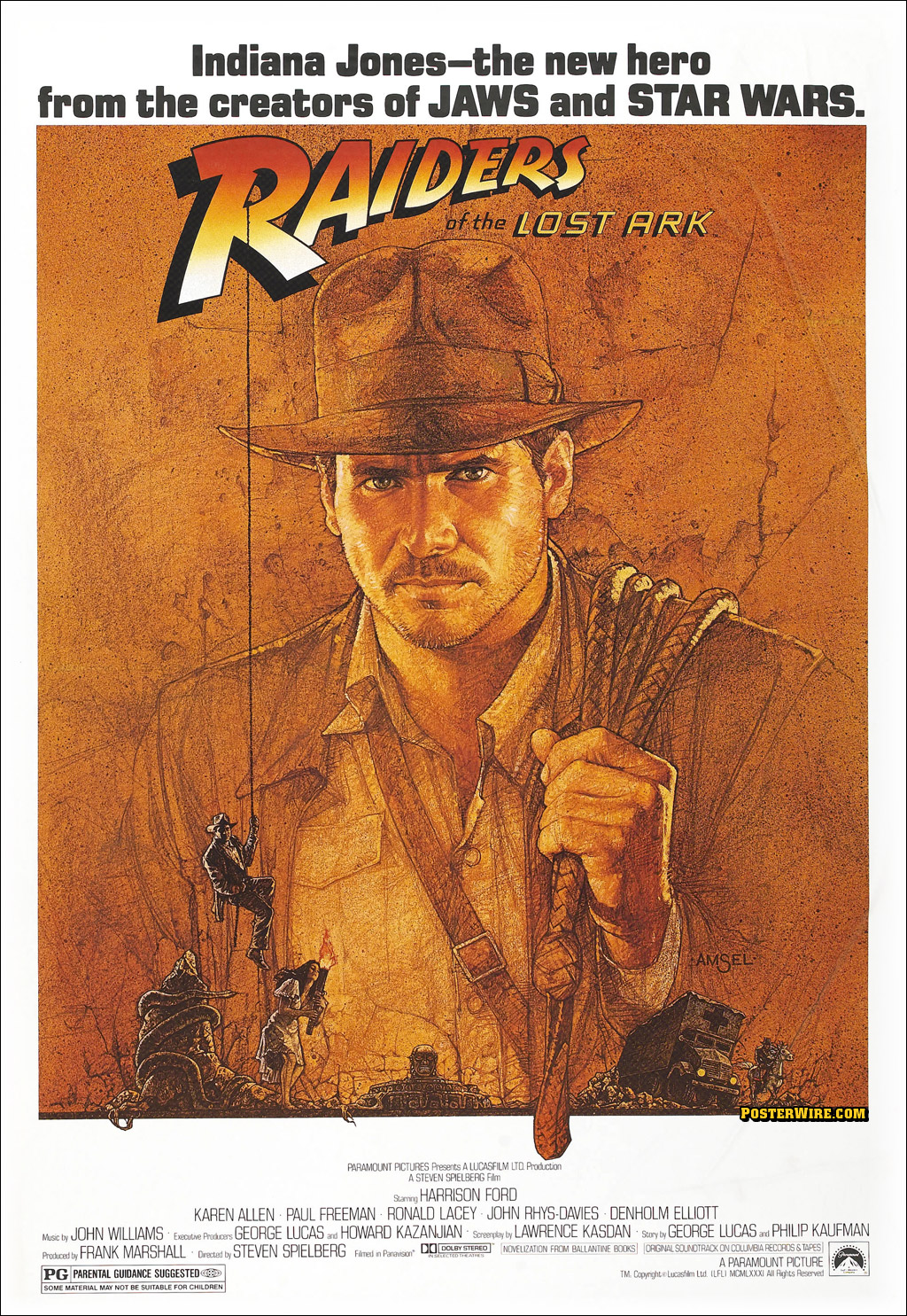

You just need to match the kind of flaw and level of intensity of that flaw to the kind of story you’re telling. For example, Raiders is a fun action flick, so we don’t need a big deep flaw for Indy. Hence, Indy’s flaw is his lack of belief in religion and the supernatural. He doesn’t care about the Ark’s supposed “powers,” because he doesn’t believe it has any. But in the end, he finally believes in a higher being, closing his eyes so the spirits from the Ark don’t kill him. It’s a very thin and weak execution of Indy’s flaw, but the story itself is fun and light so it does the job.

The problem I always ran into as a writer was that nobody gave me a toolbox of flaws that I could use. That’s why I wrote today’s article. I wanted to give you eleven (the new “ten”) of the most common character flaws that have worked over time in movies. Now when you read these, you’ll probably say, “Uhh, but that’s too simple.” Yeah, the most popular flaws are simple. And the reason they’re simple is because they’re universal. That’s why audiences find them so moving – they can relate to them. Remember that – the more universal the flaw, the more people you’ll have who can identify with that flaw.

1) FLAW: Puts work in front of family and friends – This is a flaw that tons of people relate to, especially here in the U.S. where our country is set up to make us feel like losers unless we work 60 hours a week. Balancing your personal and professional life is always a challenge. It’s something I personally deal with all the time. I work a ton on this site. And when I’m not working on the site, I’m working on future ideas for the site. That leaves me with very little time to go out and have fun. The question then becomes, over the course of the story, “Will the hero realize that friends and family are more important than work?” We see this explored in movies time and time again. Most recently we saw it in Zero Dark Thirty (in which Maya never overcomes her flaw). Or last year with Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) in Moneyball. Again, it has to match the story you’re telling, but it’s always an interesting flaw to explore.

2) FLAW: Won’t let others in – This is a common flaw that plagues millions of people. They’re scared to let others in. Maybe they’ve been hurt by a past lover. Maybe they’ve lost someone close to them. Maybe they’ve been abandoned. So they’ve closed up shop and put up a wall. The quintessential character who exhibits this trait is Will in Good Will Hunting. Will keeps the world at arm’s length, not letting Skylar in, not letting Sean (his shrink) in, not letting his professor in. The whole movie is about him learning to let down his walls and overcome that fear. We see this in Drive, too, with Ryan Gosling’s character refusing to get close to anyone until he meets this girl. We also see it with George Clooney’s character in Up In The Air.

3) FLAW: Doesn’t believe in one’s self – This should be an identifiable flaw for anyone in the entertainment industry. This business is full of doubters, especially when you’re still looking for a way in. It’s tough to muster up the confidence in one’s self to keep going and keep fighting every day. But this doubt isn’t limited to the entertainment industry. Billions of people lack confidence in themselves. So it’s a very identifiable trait and one of the reasons a main character overcoming it can illicit such a strong emotional reaction from the audience. It makes us think we can finally believe in ourselves and break through as well! We see this in such varied characters as Rocky Balboa, Luke Skywalker, Neo, and King George VI (The King’s Speech).

4) FLAW: Doesn’t stand up for one’s self – This flaw is typically found in comedy scripts and one of the easier flaws to execute. You just put your character in a lot of situations where they could stand up for themselves but don’t. And then in the end, you write a scene where they finally stand up for themselves. The simplicity of the flaw is also what makes it best for comedy, since it’s considered thin for the more serious genres. I also find for the same reason that the flaw works best with secondary characters. We see it with Ed Helms’ character in The Hangover. Cameron in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (afraid to stand up to his father). And George McFly (Marty’s dad) in Back To The Future.

5) FLAW: Too selfish – This flaw I’m sure goes back to the very first time two homo sapiens met. There’s always been someone who puts themselves in front of others. Everybody in the world has someone like this in their life, so it’s extremely relatable and therefore a fun flaw to explore. It does come with a warning label though. Selfish characters are harder to make likable. Just by their nature, they’re not people you want to pal up with. So you need to look for clever ways to make them endearing for the audience. Jim Carrey in Liar Liar for instance – an extremely selfish character – would do anything for his son. Seeing how much he loves him makes us realize that, deep down, he’s a good guy. But it’s still a tough flaw to pull off. I can’t count the number of scripts readers or producers or agents have rejected because the main character “isn’t likable,” and usually it was because of a selfish asshole main character. A few more notable selfish characters were Han Solo in Star Wars, Bill Murray’s character in Groundhog Day, and Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network.

6) FLAW: Won’t grow up – This is another comedy-centric flaw that tends to work well in the genre due to the fact that men who refuse to grow up are funny. We see it in Knocked Up. We see it in The 40 Year Old Virgin. We saw it with Jason Bateman’s character in Juno. We even see it on the female side with Lena Dunham’s character in the HBO show, Girls. I’ll admit that this flaw hit a saturation point a couple of years ago, so either you want to find a new spin on it (like Lena did – using a female character) or wait a year or two until it becomes fresh again. But it’s been proven to work because of how relatable a flaw it is. Who isn’t afraid to grow up? Who isn’t afraid of all the responsibilities of being an adult? That’s what I want to get across to you guys. These flaws all work because they’re universal. Everybody has experienced them in some capacity.

7) FLAW: Too uptight, too careful, too anal – You tend to see this flaw in television a lot. There’s always that one character who’s too anal, the kind of person you want to scream at and say, “LET LOOSE FOR ONCE!” We all have friends like this as well, so it’s another extremely relatable flaw. Joel Barish (Jim Carrey) in Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind is plagued with this flaw. Jennifer Garner’s uptight hopeful mother in Juno is driven by this flaw. And you’ll see this flaw in Romantic Comedies a lot, in order to give contrast to the fun outgoing girl our main character usually meets (Pretty Woman).

8) FLAW: Too Reckless – You’ll usually find this flaw in more testosterone-centered flicks. Like with Jeremy Renner’s character in The Hurt Locker, Martin Riggs (Mel Gibson) in Lethal Weapon, or James T. Kirk in the latest incarnation of Star Trek. The flaw dictates the character enter a lot of big chaotic situations in order to battle his flaw, so it makes sense. I’m not a huge fan of this flaw, though, because I believe the best flaws are universal. That’s why they emotionally manipulate audiences, because people in the audience have experienced those flaws themselves. Recklessness isn’t something people emotionally respond too. That’s not to say it isn’t effective and doesn’t allow for a satisfactory change in an action flick. It just doesn’t hit that emotional note for me like a lot of these other flaws do.

9) FLAW: Lost faith – This is a bit of cheat because questioning or losing one’s faith isn’t necessarily a flaw. But it’s an incredibly relatable experience. Something like 97% of the people on this planet believe in a higher being. But a majority of those people question their faith because now and then something terrible happens to shake it. Which is why you’ll see a ton of characters enduring this “flaw.” We saw it with Father Damian Karras in The Exorcist after his mother dies. We see it with Mel Gibson’s character in Signs after his wife is killed in a car accident. Again, losing someone close to us is a universal experience, so it’s one of those “flaws” that works like a charm when executed well.

10) FLAW: Pessimism/cynicism – This flaw isn’t used as much as the others, but you’ve seen it in movies like Sideways with Miles (Paul Giammati has actually made a living out of this flaw), Terrance Mann ( James Earl Jones) in Field of Dreams, and Edward Norton’s character in Fight Club. I always get nervous around flaws that make characters unlikable and pessimism tends to do that for me. For example, I never warmed to Sideways as much as others because Miles’ pessimism was so grating. But on the flip side, tons of people relate to that character for the very same reason. They’re just as frustrated with life as he is. Which is why the movie has its fans.

11) FLAW: Can’t move on – This is one of the lesser-known flaws but a powerful one. It’s basically about people who can’t move on, who are stuck on someone or something from the past. Their obsession with that past has stilted their growth, and brought their life to a screeching halt. Most famously, you saw this in Up, with Carl Fredricksen, who hasn’t been able to get past his wife’s death. But you may also remember it from the movie Swingers, where Mike (Jon Favreau) is still obsessed with the girl who dumped him. He keeps waiting for that call. With relationships being so fickle, people are experiencing this flaw ALL THE TIME, so it’s very relatable and therefore very powerful when done right.

So there you have it. You’ve now got eleven flaws to start applying to your characters. And remember, those aren’t the only flaws you can use. They’re just the most popular. As long as you start your character in a negative place and explore how they get to a positive place, you’re creating a character with an arc, a transformation. There’s more to character development than this, which I discuss in my book, but getting the character flaw down is probably the most important step. Feel free to offer some of your own character flaw suggestion in the comments section. I’ll be watching closely so I can steal the best ones. :)

Today’s screenplay is a cult classic in the spec world. Only true insiders know about it. But that’s about to change.

Genre: Biopic

Premise: Between 1996 and 2005, three enormous personalities dominated the trade headlines with their petty antics. No, this story is not about Charlie Sheen, Lindsay Lohan, and Russel Crowe. It’s about Disney Head Michael Eisner, Co-Head Michael Ovitz, and Disney #3 Jeffrey Katzenberg.

About: So here’s the deal with this script. It’s written anonymously, supposedly because the writer didn’t want to get in trouble for laying out an expose on what went on behind-the-scenes in one of the most f*cked-up marriages to ever drive a Hollywood studio. These were powerful men who made big decisions. If you’re detailing their secret meetings, you probably want to keep your identity out of it. What I don’t understand is if this script was sent out to sell, or just something Hollywood insiders passed around for fun. Either way, it’s one of those well-known cult-scripts, which means it’s high time I reviewed it.

Writer: ?????

Details: 133 pages (labeled as 1st Draft)

Let’s just get something out of the way right now. This is not a good script. It’s unfocused. It rambles. I’m not sure who the main character is. Characters always say exactly what they’re thinking (“on the nose” dialogue). It’s kind of like what would happen if an Amateur Friday writer was told to write an expose on the Michael Eisner Disney years using the same format that Aaron Sorkin did for The Social Network.

With that said, it’s a good STORY. Why is it a good story? Because you have big boys acting like big babies and people love to watch big babies pretending to be big boys. After we get past the first three-quarters of the script – which is all setup – things really start to get juicy. And confounding. And bizarre. I read the script pretty fast so I may get some of the facts wrong, but here’s how I remember it going down.

We start out, like The Social Network, at a courtroom, where Disney is being sued by its shareholders because Michael Eisner, the studio head, fired his best friend (Michael Ovitz) after hiring him just 16 months earlier, and giving him a 200 million dollar severance payout. Shareholders don’t like when you hand out 200 million of their dollars for f*cking up, so naturally they’re pissed. But before Judge Judy makes her entrance, we cut back to 8 years ago, to the year 1996.

At the time, Disney’s feature department was stumbling. The company just didn’t seem to know how to make movies anymore. So they hire Michael Eisner, who was running ABC television programming at the time, and things started to turn around. A huge reason for this was Eisner’s number 3, a smart hard-working wizard of a man named Jeffrey Katzenberg. Katzenberg was credited for making groundbreaking decisions like making Disney’s movie library available on video for the first time. He also had an acute understanding of what audiences wanted, and helped produce some huge hits for the Mouse House.

Across town, Eisner’s best friend, Michael Ovitz, was doing quite well for himself as well, starting up and running super-agency CAA. Ovitz got so many big clients and controlled so many of the elements that got movies made that he was quickly tabbed the most powerful man in Hollywood. Ovitz could pretty much do anything he wanted. He was Superman.

Back at Disney, Eisner began to get jealous of Katzenberg’s success. The man was getting a lot of credit for doing a lot of things, mainly because someone kept leaking stories about his amazing achievements to the press. Eisner suspected the culprit was Katzenberg himself. Increasingly suspicious, Eisner distanced himself from Katzenberg, a decision that would prove costly, since he had promised Katzenberg the number 2 position in the company if anything were to ever happen to Frank Wells, the current number 2. Well, Frank Wells ended up dying in a helicopter crash. Which put Eisner on the spot. Would he hold true to his word?

Apparently not. In fact, Eisner became famous for promising things to people then claiming he never said them in the first place. And according to him, he never promised Katzenberg the position. So Katzenberg fled to create Dreamworks with Spielberg, but not without leaving a hefty bill. In his contract, Katzenberg was promised more than 200 million dollars in royalties from the movies he helped make. Despite it being there in plain print, Eisner refused to give him this money. Out of pettiness? Out of defiance? It’s unclear. But he just couldn’t fathom the idea of giving Katzenberg what he was due.

Meanwhile, the hunt for a new number 2 was heating up. Eisner had to pick someone soon. But the pool of players was tiny. Eisner considered mega-friend Ovitz, but it looked like Ovitz was going to get hired to run Universal. However, in a twist of fate, Ovitz was passed over for the job by Ron Meyer, a huge blow to Ovitz’s bulletproof image. This allowed Eisner to make a play for his best friend. He knew Ovitz wouldn’t take a number 2 position. He wasn’t a number 2 kind of guy. So Eisner said, “How bout we be co-heads?” Ovitz agreed and into Disney he went.

But things started going wrong immediately. On his very first day, all of the Disney executives told Ovitz they refused to report to him. Sandy Litvack, who thought HE was getting the number 2 position at Disney, also took Frank Wells’ giant old office, putting Eisner’s “co-head” down a floor and in a small office, which didn’t make any sense. But Eisner didn’t seem bothered by the issue. Nor did he seem bothered by the fact that nobody planned to report to Ovitz, essentially ostracizing him on the first day of the job.

Ovitz had a feeling something wasn’t right, but knew jumping ship right after losing out on the Universal job would cause irreparable damage to his status and reputation. So he stayed. And it only got worse. Eisner seemed to ignore Ovitz. Whenever Ovitz did put a deal together or come up with a big idea, Eisner nixed it. Eisner seemed so set on blocking or disregarding anything Ovitz did, that Ovitz became convinced it was a setup- that he was brought in to fail. Except he couldn’t figure out why his best friend of 30 years would do something like that to him.

16 months after being hired, Ovitz was fired, given 200 million to basically go away. And that’s what he would’ve done had the shareholders not sued. But they did, which is why we get to read about this story today.

Like I said, this script is a mess. It doesn’t get good until Ovitz is hired at Disney. THAT’S where the story begins so THAT’S where the bulk of the screenplay should’ve been focused. But that doesn’t happen until page 80! Imagine if Mark Zuckerberg didn’t start Facebook until page 80 in The Social Network? And everything before that was backstory. We would see Zuckerberg in high school. How he suffered to find friends. How he barely got into Harvard. How his parents struggled to pay tuition.

Yeah, all of that would be nice to know. But it’s ALL BACKSTORY. And you can only squeeze so much backstory into a script. Audiences are much more interested in what’s happening NOW than what was happening before. The best writers figure out a way to squeeze in all that backstory yet still keep the story moving. In Two Blind Mice, I don’t need to know about Jeffrey Katzenberg’s time at Paramount. I don’t need 50 pages of what happened at subsequent studios and agencies BEFORE Ovitz showed up at Disney. I need to see Ovitz SHOW UP at Disney. Because that’s where this gets interesting.

Imagine you’re the top dog in your field. You’re heavily recruited to your best friend’s company. It’s one of the biggest splashiest marriages in your line of work. You then show up on the first day…AND NOBODY GIVES A SHIT. In fact, they SHUN YOU. Even your secretary gives you a hard time. What do you do? THAT’S a compelling character to me. What does Ovitz do in that situation? How does he survive? How does he find a way out of this? Why not follow Ovitz from page 1 and make this a tragedy? A fall from grace?

That was another problem for me, was that we weren’t following one character. We were following a group of characters. And because of that, we didn’t know who we were supposed to identify with. It’s not that that can’t be done, but often the strategy leaves the reader stranded or torn, like a dog whose owners are standing on both sides of him, both calling for him to “come here boy!” Which way do you go?

You also saw wasted scenes, such as numerous cuts to Eisner and Ovitz’s wives, who were also best friends. I don’t have any idea what these scenes or these characters brought to the table outside of maybe making it clearer that Ovitz and Eisner were close. But this is why this is a first draft. You explore these things. You go off on tangents and see what you can find. Then in the next draft, your job is to go through your script and tell yourself, “Cut everything that isn’t absolutely necessary to tell the story.” These two are not necessary, so I’m betting they would’ve become one of the first cuts.

What’s also interesting about Two Blind Mice is that it’s kind of a dual-protagonist script where we don’t like either of the characters. They’re both annoying, with Eisner being the more annoying of the two. It’s awfully hard to write a story without anyone to sympathize with (even The Social Network had the idealistic Eduardo to latch onto), and if this story wasn’t so crazy and true, this would’ve been a death knell for the script. However it is interesting that at a certain point, the writer decides to side with Ovitz, and make him the screwed-over hero in this whole ordeal. It’s almost like he realized this very criticism midway through the script and went, “Oh yeah, I have to make them like someone.” Indeed, when Eisner starts being a complete dick to Ovitz, it’s the first time we develop a rooting interest for someone.

I can see why this got passed around. It’s detailing the secret power struggle of two of the biggest titans in town. Hollywood loves themselves some gossip so passing this to a friend was a no-brainer. As a script, though, it’s messy, and would need numerous rewrites to get it where it needs to be. Still, it’s a fascinating enough story that it’s worth reading.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You have a choice with your first draft. You can either write a “vomit” draft, where you just let it all out at once. Or you can carefully outline your script so that it’s more focused and structured. A vomit draft is generally referred to as a “lazy man’s draft” because you don’t have to prep. You just write. As a result, it’s often embarrassingly sloppy, and will require 3 to 4 drafts just to get it on par with an outlined first draft. To me, Two Blind Mice (great title by the way) feels sloppy, like a vomit draft, which means way more work going forward. I’m not saying either way is right or wrong. But I will promise you that a vomit draft is going to take a ton more work to get in shape.

For the foreseeable future, every Tuesday will be a Scriptshadow Secrets type breakdown of a great movie, giving you 10-12 screenwriting lessons from some of the best movies of all time. Today will be the first entry, “The Graduate.” Next week will be The Big Lewbowski. And going forward from there, I’ll be taking suggestions. Feel free to offer potential films in the comments section, and if you like what someone’s suggested, make sure to “like” their comment so I know what the most popular requests are.

THE GRADUATE

Logline: A college graduate comes back home, where he’s pursued by one of his mother’s friends, a relationship that is tested when he falls in love with the woman’s daughter.

Writers: Calder Willingham and Buck Henry (based on the novel by Charles Webb)

The Graduate allllllmost made it into my book but, to be honest, I was a little scared of it. The movie is based around the one thing every single screenwriting book tells you not to do – include a passive protagonist. I thought, “What if I can’t figure out why it works? It’ll fly in the face of everything I’ve learned.” The good news is, I DID figure it out. What I realized was that the 3-Act structure is basically built around the idea of an active protagonist. Someone wants something (Act 1), they go after it, encountering obstacles along the way (Act 2), and they either get it or don’t (Act 3). If someone isn’t going after something, the 3 Act structure isn’t as relevant, which is why so many scripts that don’t have a goal-oriented hero fall apart. The solution then, is to offset this lack of action somehow. And you do it with one of the most common tools in the craft: CONFLICT – a central focus of this breakdown. Read on!

1) To quickly convey who your protagonist is, introduce them around people who are the opposite – This is an age-old trick and it never fails. If your hero is crazy, introduce him around a bunch of normal people. If your hero’s too nice, introduce him around a bunch of assholes. The opposing characteristics of these characters will work to highlight your own hero’s traits. So in The Graduate, Benjamin Braddock is introverted and quiet. The writers then THRUST him into his graduation party, where everyone is loud and excited. We wouldn’t have captured Benjamin’s mood nearly as well if all the other characters were just as introverted and quiet as he was.

2) If your hero’s passive, one of the other main characters must be active – If all you have is passive people in your screenplay, then nobody’s going after anything, which means there will be ZERO happening in your script. Someone has to drive the story. In this case, because Ben isn’t active, Mrs. Robinson is. She’s the one who wants Ben, who wants the affair, who pursues Ben. This is why, even though Ben is such a reactive person, stuff is still happening in the story. We have someone pursuing a strong goal.

3) The Power Of Conflict – I realized that the main reason this story works despite its main character being so passive, is that every single scene is STUFFED with conflict. Every scene in The Graduate has either a) two characters who want completely different things, or b) One character keeping/hiding important information from another character. There is just so much resistance in The Graduate. Since each individual scene is so good (due to the intense amount of conflict), it distracts us from the fact that there’s no goal driving the story forward (until later, when Ben falls for Elaine).

4) Easiest Scene to Write – One of the easiest ways to make a scene fun is to give one character a SUPER STRONG GOAL and give another character the EXACT OPPOSITE GOAL. This creates conflict in its most potent form, which leads to a high level of drama. It’s no coincidence that this approach created one of the best scenes of all time, Mrs. Robinson trying to keep Ben at the house and seduce him (her goal) while Ben is trying desperately to escape and avoid her seduction (his goal).

5) STAKES ALERT – Notice how when Mr. Robinson invites Ben to a nightcap, he says, “How long have your dad and I been partners?” This is a HUGE piece of information as it raises the stakes in Ben and Mrs. Robinson’s relationship considerably. If the only thing at stake in this affair is Ben’s pride or emotions, that wouldn’t be enough to drive an entire movie. But screwing up his father’s business, that’s a whole different ballgame. You want to make sure the consequences for your characters’ actions are as big as they can possibly be.

6) MID-POINT SHIFT ALERT – The Graduate has one of the best mid-point shifts I’ve ever seen. Elaine, Mrs. Robinson’s daughter, comes back from school. She and Ben are then set up. The whole second half of the movie now moves to Ben’s relationship with Elaine while he tries to fend off a scorned Mrs. Robinson. Like all good mid-point shifts, it adds a new wrinkle to the story that keeps it fresh. Had they stretched Ben’s relationship with Mrs. Robinson across the entire story all on its own, the movie likely would’ve run out of steam.

7) Cheating/Infidelity scripts must be PACKED with dramatic irony – When you have a character cheating or a couple hiding a relationship from others, you want to put them in as many situations as possible where there’s dramatic irony. For example, when Ben first meets Elaine before their date, Mrs. Robinson is in the room, leering at them from the corner. Same with an early scene where Mr. Robinson invites Ben for a nightcap and Mrs. Robinson (who just tried to seduce Ben moments ago) enters the room. We feel the tension because of the secrets Ben and Mrs. R share. These situations also lead to some great line opportunities, such as when Mr. Robinson says to his wife, “Doesn’t he look like he has to beat the girls off with a stick?” “Yes,” she replies. He does.

8) The “Bad Date” Scene – The Graduate did something really cool that I’ve never noticed before. The story needed to show Ben and Elaine fall in love quickly because Elaine had to go back to college and we had to believe Ben had fallen in love with her enough to chase her there. Normally, I see writers writing these “lovey-dovey” scenes to prove their leads’ love to the audience (see Star Wars Episode II: Attack Of The Clones). For whatever reason, these scenes often have the opposite effect, making us nauseous and annoyed by the couple. So The Graduate takes the COMPLETE OPPOSITE approach. Ben’s only going on a date with Elaine because his parents make him. In order not to piss off Mrs. Robinson, he’s a total bitch to Elaine all night, taking her to a strip club and embarrassing her on stage. It gets so bad that Elaine starts crying, making Ben realize how much of a jerk he’s been. He apologizes, which leads to their first kiss. Experiencing a traumatic night instead of an ideal one thrust them much deeper into their relationship, adding the kind of weight to their experience a “happy” date just wouldn’t have been able to achieve. So the next time you write a first-date scene or need to accelerate a relationship, consider your characters NOT getting along instead of getting along.

9) SCENE AGITATOR ALERT – Remember, you should always look for ways to make it difficult on your hero in a scene, especially when they want something badly. So when Ben finally gets to Elaine’s college and spots her getting on a bus, he follows her on in an attempt to win her back. Except Ben isn’t able to sit next to Elaine because someone’s already sitting there. He’s forced, instead, to sit diagonally behind her, meaning he has to lean forward at a weird angle to make his case. It’s awkward. It makes his task difficult. And that’s exactly what you want to do to your character. If it’s too easy, you probably aren’t getting enough drama out of the situation.

10) “Crash the Party” moment – Whenever something’s going too good for too long for your protagonist, “crash the party.” In other words, bring them back down to earth. So later in the movie, after Ben’s chased Elaine to her college and the two have spent multiple scenes having the time of their lives together, Ben arrives back at his hotel to find Mr. Robinson waiting for him. He crashes the party, informing Ben that he knows about the affair, and that there’s no way he’s letting Ben anywhere near his family from this point forward.

These are 10 tips from the movie “The Graduate.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Inception,” “When Harry Met Sally,” and “The 40 Year Old Virgin,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

First off, I just want to thank everybody who’s written in recently to say how much they’ve gotten out of the site the last few years, from the guy who just started writing a couple of weeks ago to even a couple of well-known Hollywood directors. It appears that while there was a highly vocal negative minority, there are thousands of writers/agents/producers/industry people who love the site and just don’t get into the politics of it. It almost made me reevaluate my decision. But for the time being, I’m encouraged by the new format. Change forces you to see everything in a new light, which often leads to new exciting ideas. And I want to explore some of those ideas in the months ahead.

For now, Monday will usually be a screenwriting-centered review of a new movie release (like today’s). Tuesday is going to be a “10 Screenwriting Tips You Can Learn From [Famous Movie]” article like the format I use in my book (this week’s is The Graduate). Wednesday is going to be a bit of a wild-card, but I’m going to try and use it to review unknown/weird/infamous/interesting screenplays from the past. Thursday will be an article. And Friday will be Amateur Friday.

Also, reviewing recent spec sales isn’t totally dead yet. The big complaint from the detractors seemed to be that I publicly posted reviews and/or sent scripts to people. So, once a week, privately via my newsletter, I’m going to review a recent/hot screenplay. These reviews won’t be posted on the site and you’ll have to go searching for the scripts yourselves, but at the very least, you’ll still be able to see what’s making noise in the industry and learn some screenwriting lessons in the process. It’s not ideal. And it sucks we won’t be able to discuss them. But it’s something. So if you’re not already on my mailing list, you’ll probably want to get on it now.

The Scriptshadow Labs will work its way into the line-up as I piece it together (a Macbook implosion and extensive data-recovery process has slowed things down a little – but don’t worry – we’ll get there). And I’ll probably be using the Tuesday and Wednesday slots to try some new stuff here and there. Here’s to seeing where it all goes! And now, Gangster Squad…

Genre: Crime/Period

Premise: A gang lord in 1949 Los Angeles becomes so big that the only way the cops can handle him is to go off-book and wage a war against his empire.

About: Gangster Squad (here’s my old script review – sorry, still haven’t gotten comments transferred over yet) is based on a number of articles from 1940s Los Angeles newspapers. In an offbeat choice, it was directed by Zombieland director Ruben Fleischer. It stars Ryan Gosling, Sean Penn, and Emma Stone. The script, written by newcomer Will Beall, was very well-received around town. Beall has since been announced as the writer for the Justice League movie. His other LA cop drama, L.A. Rex, landed high on the 2009 Black List, which is what jump-started his screenwriting career.

Writer: Will Beall (based on the book by Paul Lieberman).

I’m just going to say it. Ruben Fleischer was probably too light-weight of a choice to direct this. I’m all for taking chances on writers and directors. It’s one of the few ways careers can advance in this industry. But that’s the thing with taking chances. There’s a chance they won’t work out. I’d totally forgotten who’d directed this when I went to see it the other day, so I didn’t go in to pre-judge the directing by any means. But when I left, all I could think about was how light-weight the film felt. The look was too glossy (strange choice for a movie about gangsters). The sets (like the Chinatown sequence) felt overly “set-like.” And the casting, outside of Sean Penn, felt uninspired.

I mean this is actually a cool idea. There’s an untouchable gangster running LA. The police can’t compete with him legally. So the chief puts together an off-the-books “squad” who can act with impunity to take him down. Everything, however, depends on the casting of that squad. And here we have Josh Brolin, who’s plagued with a deadness to his acting. We have Anthony Mackie, who plays the African-American officer, who has zero film presence. We have the T-1000 himself, Robert Patrick, who screams “B-Movie.” We have Michael Pena, who’s as light and feathery as a crepe. And we have Giovanni Ribisi, who’s a great actor but doesn’t leave much of an impression here.

Even the major talent, Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling, feel like they’re acting more in a school play about gangsters than a 100 million dollar movie. There’s very little chemistry between the two and Gosling doesn’t carry one-tenth the weight he did in Drive. And Emma Stone just looks happy to have gotten this role so she can stretch her acting chops. Though she proceeds to do so mainly by batting her eyelashes and whispering a lot.

The only actor who carries any weight in this movie is Sean Penn, who is so far above all the other actors that his performance actually backfires, shining a light on just how over-matched everybody else is. As a first-time director, I’m not sure how much the studio bullied Ruben into these casting choices, but from my experiences, it’s usually the big actors that the studio pushes on the director, while letting them choose the lesser guys. And the lesser guys here were the movie’s downfall. The Squad was supposed to be badass. Unfortunately they turned out half-ass.

Which is too bad, because the script itself is pretty decent. It’s not great, but it’s improved from the older draft that I read in July. For those unfamiliar with the story, here’s a quick breakdown:

There’s this mob boss, Mickey Cohen, who’s running Los Angeles into the ground in 1949. If something isn’t done soon, the city will never recover. Enter Sgt. John O’Mara (Josh Brolin) the only clean cop in Los Angeles. He’s recruited to scramble together a “Gangster Squad” to take Cohen down. His key recruit is Sgt. Jerry Wooters (Ryan Gosling) a young selfish cop who finds it’s much easier to let the nasty dogs bark than get in the cage and shut them up. But when the bad guys kill Wooters’ shoe-shine kid (yes, one of the more unfortunate choices in the script), he does a 180, becoming O’Mara’s Number 1. Things get complicated, however, when Wooters falls for Cohen’s girl (played by Emma Stone).

First thing of note here is that the structure is pretty solid. You have the goal (Take down Mickey Cohen), the stakes (if you don’t, Los Angeles crumbles) and eventually the urgency (Cohen is constructing the only wire between Chicago and LA. If he completes it, which will happen by the end of the week, they’ll have no shot against him).

I’m pretty sure this ticking time bomb was an addition to the draft that I read, and it’s something I’ve been noticing more of lately. Some movies won’t establish their ticking time bomb right away. They instead choose to add it later, usually around the midpoint, as a way to up the stakes, as is seen here in Gangster Squad. Just as they’re getting a handle on Mickey, they find out about this wire he’s building which will give him absolute power. And they only have a week to stop it.

Still, I’m always nervous when long stretches of a screenplay don’t have SOME urgency attached to them. Which is why it might be a good idea to offer a temporary ticking time bomb before the major one arrives (if you choose to have the late arriving TTB). So in Gangster Squad, for example, maybe the word on the street is that the Mayor (who’s on Mickey’s payroll) is replacing Police Chief Parker with one of his guys any day now. So Parker makes it clear to O”Mara, “We don’t have a lot of time.” I’m not pretending this is a great idea. I’m just saying it never hurts to look for ways to create an immediacy to your protagonist’s actions.

Now, on the plus side, we have some pretty good (but not great) character development here. On Friday, I criticized the lack of character development in “The Last Ones Out,” saying that there were no real choices that the characters had to make. And character development is about establishing a flaw in your character, then giving him choices that challenge that flaw.

Take O’Mara for example. His flaw is that he puts his work above his family. When he’s given a choice early on to either do what’s safest for his family or form the Gangster Squad, he chooses the Gangster Squad. Over the course of the story, as things get more and more dangerous, he continues to choose his work over the safety of his family. This is character development. Tell us what defines your character, then throw choices at him that make him face this flaw in himself head on.

When it was all said and done, Gangster Squad left me appreciating what Scorsese does a lot more. The film will make Fleischer a much better director in the long-run, but learning the challenges of making a movie like this definitely had an effect on the final product. Gangster Squad failed to do the job for me.

[ ] what the hell did I just see?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Lately I’ve been wondering if there’s a fault in the 3-Act structure. 95% of the movies and screenplays I see get late into the second act and experience this 10-15 minute “boring as hell” lag where all the relationships get resolved and slow dialogue scenes get stacked on top of each other, and the momentum is just sucked out of the story. Gangster Squad was just good enough to keep me watching, but once it hit that Late Second Act, it lost me for good. Specifically the scene where O’Mara and Wooters are sitting on the back porch, drinking, and talking about how things suck. I honestly haven’t figured out the best way to deal with this troubled section. You obviously need to wrap certain storylines up before the climax, but if there are too many “wrap-up” scenes in a row, you lose the audience/reader. Part of the problem may have been the huge character count in Gangster Squad. Too many characters, most of whom we don’t know (who the hell was the guy who hung out with Emma Stone the whole movie??), meant wrapping up character storylines we just didn’t care about. Maybe that’s the big lesson to take away from this. To lessen the length of this potential pitfall section, only include characters you absolutely need in your story. They’re the ones we’ll care about, and therefore the ones whose relationships we’ll WANT to see resolved late in the second act. Even still, I would try to keep this section as short as possible. It kills the momentum of so many screenplays/movies.

Today’s amateur zombie screenplay poses the question – What is character development really?

Amateur Friday Submission Process: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, a PDF of the first ten pages of your script, your title, genre, logline, and finally, why I should read your script. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Your script and “first ten” will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effect of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title for your screenplay. To help vote for contending amateur script and to stay up to date on which scripts will get reviewed, join my mailing list. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Drama/Zombie

Premise: (from writer) In a quarantined post-viral New York City, Elaine and Cora, two survivors with a strong stance against killing the infected, collide with two brothers who take the exact opposite approach.

About: Today’s writer used this zombie short to get into NYU, which was shot in a couple of days with minimal help.

Writer: Avishai Weinberger

Details: 109 pages

I know what you’re saying. “Another zombie script?” Well there might as well be an echo in the room because that’s exactly what I was thinking. The good news? We’re not alone. Today’s writer began their e-mail with, “I know what you’re thinking. Another zombie script?” So we’re all on the same page here. We’re all worried that this is going to be “just another zombie script.” But! Our guest of honor promises that they’re doing something different, focusing more on character development than zombie slurpage.

And that’s a big reason why I picked this. When writers want to write character pieces, they all have different ideas on what that actually means. Some think it means all of their characters should talk about deep issues and traumatic childhood experiences’n stuff. That’s not character development. That’s boring. What DOES character development entail? Read on to find out.

The Last Ones Out starts with two friends in their late teens stuck in a post-apocalyptic Brooklyn. There’s 17 year old Cora, a mute, and 18 year old Elaine, an alpha female. The pair spend their days looking for food and fending off the occasional zombie. The zombies here are a little different from the kind we’re used to. They look confused, almost afraid. But when they get hungry, they have no problem turning you into a four-course meal.

But as strange as the zombies are, it’s not half as strange as how Elaine deals with these gimpy goofballs. Instead of shooting these bastards square in the forehead like our zombie-killing ancestors have taught us to do, she lures them out into the open and sets them free. She lives by a Terminator 2 no-casualties mantra.

Back in their apartment, Elaine does her best to care for the ailing Cora, who it appears still hasn’t recovered from the trauma of the apocalypse (hey, can ya blame the girl?). So her main focus outside surviving is bringing loopy Cora back to the land of the living, so to speak.

Just as Elaine’s about to give up on a rescue, the duo are visited by two brothers, 24 year old Joseph and 20 year old Ben (Surviving the apocalypse appears to be a young man’s game). While there’s some initial reluctance from the girls, the guys seem pretty genuine, so they let them in. The real point of contention in the group comes later, when Elaine finds out that Joseph is a shoot first and ask questions later kind of guy. Or in other words – a zombie killer! Elaine is not cool with this and gives him the John Connor speech about how you can’t just kill people. Err, Joseph points out, but they’re not people. They’re zombies.

Despite their differences, the group will have to work together when they find out an army is awaiting survivors on the other side of the Brooklyn Bridge. All they have to do is make a trip to an abandoned hospital, get a few things the military is requesting, and hope they don’t run into any zombies along the way. Yup, I’m sure that’s going to happen.

There’s a lot to learn from The Last Ones Out. Avishai definitely did some things right. There’s a really smooth easy-to-read writing style here and a solid third act. But the first two acts move way too slow and simply don’t have enough direction or meat to keep the reader riveted.

Let’s go back to that question about character development. That’s what Avishai wanted to do here – explore the characters. Was it a success? Well, in my opinion, the characters here weren’t that interesting. I was kinda annoyed by how Elaine wouldn’t kill zombies. And I was frustrated (and often confused) as to why Cora wouldn’t talk. The relationships weren’t that interesting either. There was only minimal conflict between anyone, and the key relationship, between Elaine and Cora, was more confusing than anything (although I’ll admit the confusion was alleviated via a 3rd act payoff). I felt the characters’ frustration and loneliness and fear. But because the interactions were so static and neutered, I didn’t feel like anything was developing on the character front.

How can this be fixed? Well, one of the best ways to explore your characters is through their choices. Put difficult choices in front of characters and you’re going to see them develop right in front of our eyes. Let me give you a generic example. What if Elaine and Cora are running out of food and they’re both on the brink of starvation? Elaine knows this. But she’s indicated to Cora that everything’s fine. Does Elaine sneak the food for herself, letting Cora continue to starve? Does she share the food, even though it’s not enough for both of them? Or does she selflessly give all the food to Cora? How she reacts to this problem gives us insight into who she is. Then maybe later, when circumstances get even more dire – when they’re literally down to their last piece of bread – does she change? Whereas before she shared the food, maybe now she fights for it. What we’re seeing before our eyes is a character developing. She’s changing. Choices are a great way to show this.

Or we can use one of the most common zombie tropes there is. Someone gets bit. They’re going to transform soon. Do our characters kill them or save them? This is a compelling CHOICE because it gets down to the core of who a character is. Are they selfish or loving ? This was kind of explored later on with Ben but it was 70-80 pages into the script. We needed compelling moments like this in the first and second acts as well.

Which leads me to probably the biggest problem with The Last Ones Out. There’s no goal for 60 pages. There’s no direction, no plan, outside of occasionally spray painting messages to fellow survivors. As I’ve said before, it’s not that a lack of a strong goal can’t be done in a screenplay. It’s just that it becomes infinitely harder to tell your story because your characters aren’t actively going after anything. They’re sitting around. And there’s too much sitting around here. The only time that really works is when there’s a TON of conflict within the group, creating lots of drama . But as I said before, there’s no real conflict inside of any of the scenes in the first and second act.

How do you fix the goal problem? Just give them a goal that’s important. In the story, Elaine’s cell phone works (for the record, I didn’t think the cell phone storyline made sense. It created too many questions). But it’s a mystery why it works. So maybe their goal is to find the cell towers, or find the cell headquarters, so they can see if there’s anyone running the system. That’s their current search. Now, instead of just wandering around for the occasional (and cliché) food hunt, they’re looking for something more concrete. Remember guys, characters ALWAYS NEED A PLAN. A plan means action. And you want to keep your characters active.

When your characters are NOT actively going after things (when they’re home at night), you need to figure out other ways to keep your reader interested. Readers don’t give out “mulligans” when they’re reading. They don’t say, “Oh, you just had that big outdoor scene so I’ll let you write two slow boring scenes now.” Unfortunately, it doesn’t work like that. If a reader’s bored, they check out. Which mean EVERY. SINGLE. SCENE. has to be interesting in some way.

(Spoilers follow) So, for example, let’s say we establish Cora as a zombie early on. But Elaine has been using a combination of medicines to keep her from turning all the way. When the boys show up, she has to hide this secret. She knows if they find out, they’ll kill Cora. So now there’s way more tension during the scenes because Elaine is hiding something. And the boys (who should probably be older and more sinister in the new version – they’re too docile here) are starting to get suspicious. That way, even your slow scenes have something going on in them. I know this is kind of explored with Ben later in the script, but again, it was too late. This direction would also allow a more logical reason for why they raid the hospital. Elaine needs more meds for Cora (the whole “military needs us to get meds” thing was obviously only thrown in there to create a late set piece at the hospital. Be careful not to unnaturally force plot points into the story. Good readers always spot them).

(major spoiler in this paragraph) There are a bunch of other little things I wish I had time to get into (I’m kind of preoccupied figuring out what the posts are going to be next week) but let me say a couple more things. I think you need to change the relationship between Elaine and Cora from friends to mother and daughter. I just never bought that Elaine would become so obsessed with nursing a zombie back to health who she never knew in the real world, to the point where she refused to kill any other zombies. But if it was her daughter, that would be different. I’d buy that.

Despite some fairly extensive criticism here, I wanna point out that the final act of The Last Ones Out was quite good. You have to do a better job setting up the army’s introduction, but the revelations and the urgency and the intensity of the final act – all of that was done quite well.

Going forward, I would also ask yourself, “What’s different about my zombie movie?” I think you need to find a more unique hook here. You’d probably counter, “Well my zombie script is more character driven.” Yeah but really, any good zombie flick should have character development. The “not killing the zombies” angle is sort of hook-y, but I don’t know if it has the weight to make a producer go, “I want that now!.” So I’d try to improve the hook.

Congrats on finishing this, Avishai, and thanks for letting me read it. Hopefully my notes will help improve the next draft. :)

Script link: The Last Ones Out

[ ] Wait for the rewrite

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In any movie, you want the climax to be the hardest thing our protagonist battles through. Every possible way you can make things more difficult for your characters during the climax? DO IT!. For example, I didn’t like how that they got to travel to the army base during the day, where it was easy to spot and avoid zombies. Why not force them to go at night, when the zombies are the most active and it’s harder to spot them? You gotta make it difficult!