You’ve got your bloody fangs out. Savoring the sweet succulent flesh of a fresh batch of Halloween Showdown enchiladas. This time with a twist! OOOH-OOOH-AH-AH-AH! Short stories ARE ALSO ELIGIBLE FOR THE MADNESS. Hollywood keeps buying these things. Well, Scriptshadow has finally listened. The controversy surrounding this decision has been PLAGUING the comments for months. I’ve had to ban at least two hundred people! That’s how dramatic this showdown is going to be.

I also received tons of entries. Too many entries that had to do with people getting in cars/staying at houses/getting jobs and then realizing someone else at that location was secretly a demon or a monster. That was literally every 6 out every 10 entries. I was trying to find stuff that had a little more creativity to it. I only have one caveat for complaining in the comments for picking one of the below entries over yours. Please make your argument with plenty of Halloween puns. Thank you.

If you haven’t trick or treated at the Amateur Showdown house before, here’s how the pumpkin is carved. Read as much of each screenplay/story as you can, then vote for your favorite in the Comments Section. Voting closes on Sunday night, 11:59pm Pacific Time. Winner gets a revieboo next Friday. If you have ideas on what the next Amateur Showdown genre should be, let me know in the comments.

One last thing. A shout out to Magnus, who EASILY had the best concept of all the entries. His script was titled Shalloween and here’s the logline – When all the hottest girls in a small town get slaughtered by a masked serial killer, a social media influencer obsesses over why she’s not hot enough to murder, and starts looking for an alternate explanation for the killings. How great is that? The problem? First two pages I read were not good. Maybe you guys can get in there and help him out. Basically, my advice is ‘write the script.’ Stop trying to be clever. It’s a good premise so it doesn’t need you to dress it up with a whole fancy way of telling the story.

Six entries this month. GOOD LUCK!

Title: Deep

Genre: Horror/Thriller (Screenplay)

Logline: Trapped on a remote North Dakota farm in the middle of a bone-chilling winter storm, a deaf 12-year old girl must try to survive her murderous foster parents, who’ve been influenced to kill by a mysterious radio signal from deep space.

Why You Should Read: Deep came about from my desire to write a story putting the most vulnerable type of person in the most terrifying situation I could imagine. A very early draft of Deep made this year’s Page Quarterfinals. After feedback, it’s since gone through a strenuous rewrite. At 87 pages, and tightly structured, it’s a lean, electrifying read. Looking forward to any critiques from the Scriptshadow Community.

Title: An Innocent Bloodbath

Genre: Period Horror (Screenplay)

Logline: Obsessed with beauty and terrified of aging, the recently widowed Countess Elizabeth Bathory will stop at nothing to preserve her perfect skin, leaving the servants in her castle absolutely horrified.

Why you should read: The story of Elizabeth Bathroy is terrifying, and she is perhaps the most notorious serial killer in history. What makes it even more unnerving, is that her victims were all young women. To date, I’ve yet to see a depiction of Elizabeth Bathory that I felt was true to the original story. Sure, Daughters of Darkness was great, but it had its own spin on it. I wanted to write a horror film, as close to the original tale as I could. Also, what made it difficult was I didn’t want to write a torture porn flick. This is not an Eli Roth movie. I’m going for atmosphere, the fear of the unknown, the fear of losing your loved ones, the fear of being snatched away in the dark of night never to be seen again, all the while following a mad woman’s quest for eternal beauty.

Title: Good Night’s Sleep

Genre: Horror (Short Story)

Logline: A young woman records herself sleeping one night and discovers a sinister presence is sleeping in her bed each night.

Why You Should Read: You should read this story because it’s a quick, but layered horror story that twists the found footage genre into a classic scary tale that wraps itself up in a nice bow (which is very hard for me to do) and reads almost more like a short film than a literary-language heavy short story.

Title: Fade Out

Genre: Horror/Noir (Short Story Screenplay)

Logline: Los Angeles, 1940 — a man paid to cover up Hollywood scandals must confront a supernatural killer hellbent on revenge.

Why You Should Read: “Fade Out” was born from two fascinations: the slasher subgenre and the sordid secrets of Golden Age Hollywood. Wanting to put a new spin on the tried-and-true “masked killer” formula, I realized I had never seen a period slasher flick before. “LA Confidential” meets “A Nightmare on Elm Street” struck me as a fun premise. Although I had an outline for a feature-length screenplay, I decided that condensing the material into a short story would act as a good “proof of concept.” Thanks for reading!

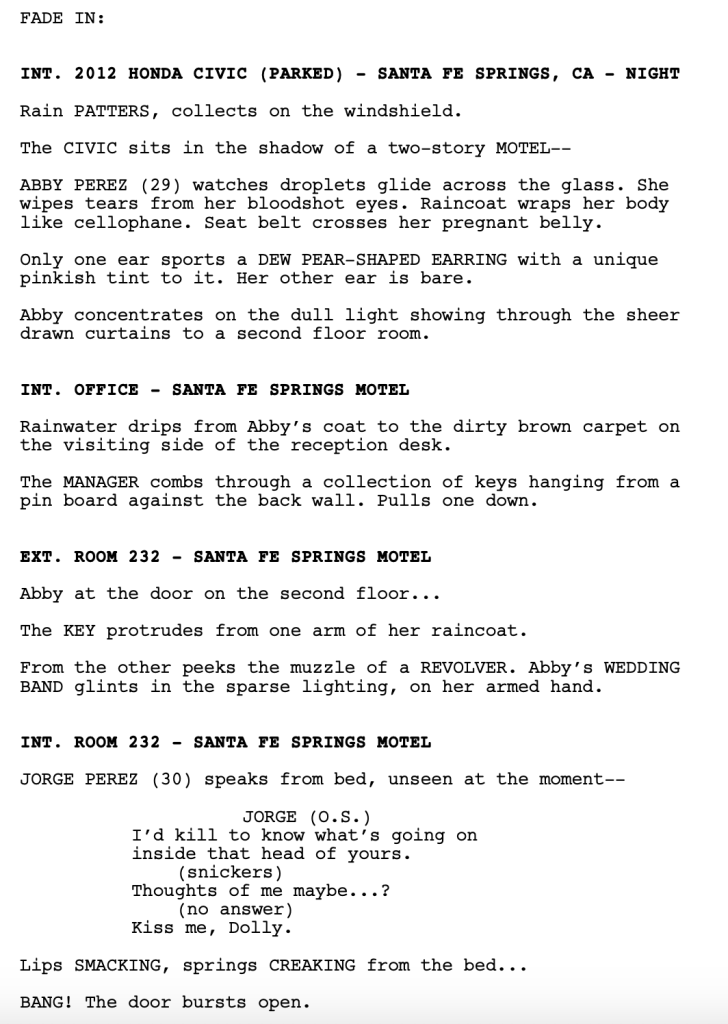

Title: Dolly

Genre: Horror (Screenplay)

Logline: A lonely teenage boy finds companionship in a sex doll, only to discover that it is possessed by an unsettled soul that will do whatever it takes to keep its young owner’s attention all for itself.

Why You Should Read: I may have dropped “something” when this was conceived of at the onset of quarantine…in the throes of my trip, I unloaded the idea on my roommate – a sex doll comes to life to possess the love of its young owner at all costs…or maybe I just said killer sex doll.

Unlike previous iterations of sex dolls on film – LARS & THE REAL GIRL among others – DOLLY comes at the idea from a strict horror perspective, falling more within the wheelhouse of CARRIE and CHILD’S PLAY. The script explores the darker edge of growing up, especially in the age of instant gratification.

DOLLY was a weirdly cathartic experience for me; it had me exploring moments of growing up, albeit through a hyper-stylized way. It became an exploration of the feelings and urges that sometimes overwhelmed my better judgment. For such a crazy premise, the story drifted into very real territory.

My biggest hope is that you find the fun (maybe even a little bit of heart) within DOLLY and it leaves you with some very memorable set pieces to haunt your thoughts this Halloween season.

I hope you find the above interesting enough to crack open the script. If not, thank you for even the momentary passing thought. I appreciate all notes, good and bad and everything in-between.

Thank you again for giving DOLLY the time of day.

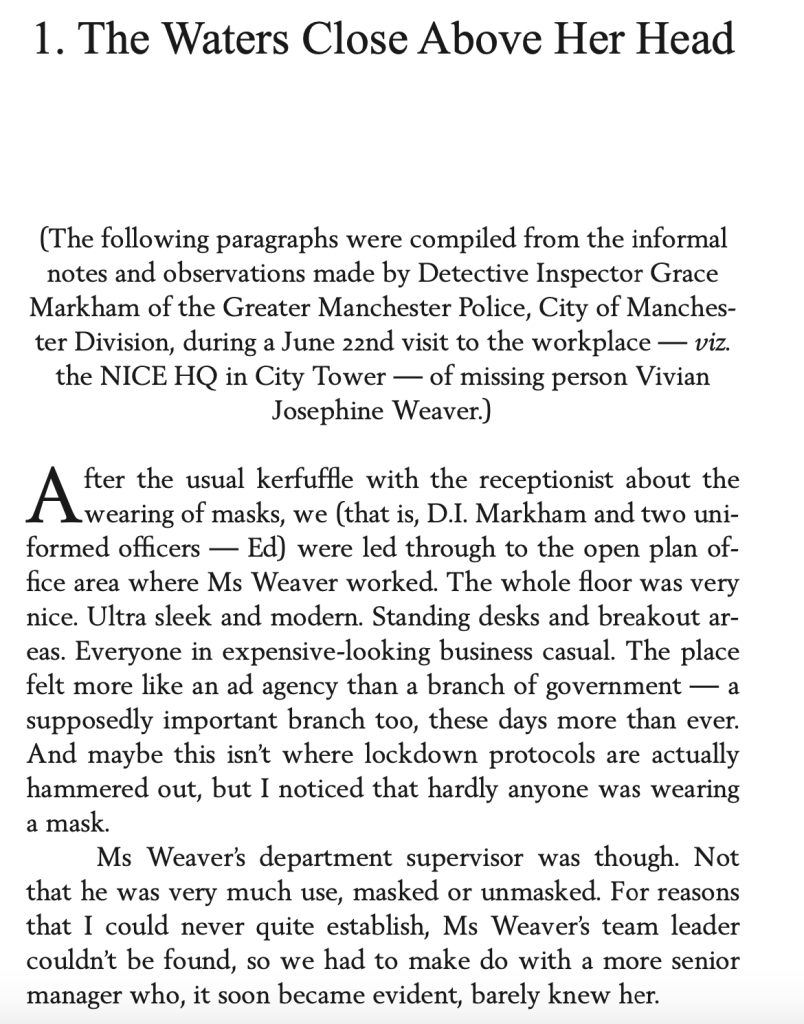

Title: My Compassionate Heart

Genre: Horror (Short Story)

Logline: During Covid lockdown in the UK, a lonely young woman falls in love with the restless ghost of a murdered sailor.

Why You Should Read: I work as a reporter in the UK. If you read the papers and take any notice of bylines, you might even recognize my name, but I’m not going to reveal it here, because the source materials for this document consist of confidential files that were exfiltrated from the Police National Database (PND) during their recent massive (2~4TB) data leak. A small number of these leaked files were sent to me anonymously by an unknown party. As far as possible, I have verified that both the files and their contents are genuine, accurate and true. I have chosen to share this information because I believe that disclosure of the strange events surrounding the disappearance of Vivian Josephine Weaver falls clearly within the wider public interest.

A few weeks ago I read the Black List rom-com that sold to Sony, Voicemails for Isabelle. It was easily the best rom-com I’ve read in years. The dialogue, in particular, was great. I said in that review that I would leave a voicemail for Leah and, what do you know, she replied! So we got on the phone and talked all things “Isabelle.” Leah was really forthcoming with her answers, which led to a great conversation. A little background here. Leah was an actress first. So you’ll see us referring to her acting throughout the interview. I also wanted a lot of dialogue advice so I asked a bunch of dialogue questions. Enjoy!

CR: The state of rom-coms in the last 15 years has been pretty bad. I think it’s because the genre is so inherently formulaic. How do you, Leah, approach the genre in order to stand out?

LM: I didn’t really know what I was doing and, in a lot of ways, that was my saving grace. Not just in rom-coms but in writing. I have no training in writing. And I agree with you. They’re so formulaic. I’ve seen a lot of rom-coms so I know the structure I have to follow in order for the audience not to get angry with me. But on some level I try to infuse it with some story about humans and sisters – my sister is my life and my love and my biggest supporter.

CR: And the inspiration for the story, I’m assuming.

LM: Yes, so what happened was I moved to LA to become an actress and my sister stayed in New York and I would leave these long voicemails to her late at night hoping to make her laugh. Or detail a terrible date. And in a lot of ways they became these confessional moments for me. The story was born out of that. I don’t know how to “write a rom-com.” All I focused on was telling my story. (for those curious, Leah’s sister is alive and well, so no tears need to be shed today)

CR: You reference a lot of rom-coms in the script so I think you know the genre better than you’re giving yourself credit for.

LM: Maybe! Yeah, I guess I do. I kinda feel it in my bones a little bit. Like I know at a certain point, “She needs to lose the guy here.”

CR: So your writing is instinctual?

LM: Yeah, that’s how I’d put it.

CR: How did you sell the script to Sony?

LM: This is going to be a long answer because it started back when I wrote and produced my first indie film, M.F.A. (a film about a rape at college). Cause I was running around asking everyone “How do you get an indie film financed?” And I would read all these sites and nobody would give me any concrete answers. So I would ask friends, “How do you do this?” And they would say, “Oh, you’ll find people,” And I would say, “But where are the people?” [laughs]

So I bought all the “How to Finance A Film” books and they weren’t very helpful either. None of them gave you a clear path on what you were supposed to do. Finally, I told everybody I knew that I was making a feature film and did they know anyone who’d be interested in investing in it. It was a slow process. Lots of dead ends. Lots of ‘this person leading to this person.’ But little bit by little bit we cobbled it together and shot it for $250,000, which included all the money I had at the time. The film got into South by Southwest and that gave me some legitimacy as a writer.

CR: Wow, you went all in.

LM: [laughs] I went all in in a way I do not recommend. Whenever filmmakers tell me they’re going to max out credit cards to make their film, on some level, I’m like, “Yeah! Do it or die!” On another level I’m like, “Self-care is important. Don’t do what I did.” [laughs] Because I came out of it so destroyed. I mean, in the midst of making that movie I was in so much pain because I was not eating. I was running on adrenaline. I ended up at the urgent care center. Anything that went wrong on the movie I took so personally in a way that you shouldn’t. I just want to say to people that I don’t think you should have to kill yourself for a movie.

CR: Yes, killing is bad.

LM: Right, and from that, I got my first literary agent. As well as my literary manager. And I got sent on the water bottle tour. Which is you go and you meet every single production company who liked your movie. And they’re all like, “What do you want to do next?” And I didn’t understand what I was doing at any of these places. I didn’t understand that I was supposed to be [laughs] pitching things. So I was sitting there thinking it was a friend date. I’m chatting and drinking my free coffee. So I said, “I don’t know what I wanna do next. Something cool I hope.” And I’m like, “Are you going to hire me now? What is happening?” And they all said, “Well, we’ll stay in contact.” And I was like, “Cool, we’ll stay in contact. Whatever that means.” [Carson laughs]

So during that tour, I met a producer named Becky Sanderman and we became really good friends. Becky pitched a TV show to me called, “What The F*ck, Glenn” about a mother dealing with her husband committing suicide. So I wrote that and that got me connected with Becky and Escape Artists, who are on the Sony lot. That led to me writing a father-daughter zombie project. And, for the first time in my life, I had a million voices giving me notes and I didn’t know how to handle it. Cause keep in mind, I was the only voice on M.F.A. I got so frustrated by the process that, in an act of rebellion, I wrote Voicemails for Isabelle. And one day Becky asked me if there was anything else I was working on and I told her about Voicemails and she said, “You are sending that to me as soon as you finish it.” And that’s what led to Sony buying it. I know that’s a long answer but I also know how frustrating it is for writers trying to understand how something gets sold so I wanted to be as detailed as possible.

CR: I’m not surprised it sold. I think you have a really strong voice, particularly your dialogue. Can you tell me your general approach to dialogue?

LM: My acting teacher John Rosenfeld always said, “Your characters are not as emotionally articulate as you.” People are not emotionally articulate most of the time. If you know that a character is heartbroken or sad, that doesn’t always come out as “heartbroken” and “sad.” People will try to play every emotion before they do that. They will get angry. They’ll be mean. They will turn it into a joke. So I very rarely play act a true darkness. We’re always trying to avoid that as humans. So a lot of times in my script where something sad has happened, there’ll be a scene that’s funny. I don’t do a lot of, “She cries and he holds her.” I don’t find that in my own life very often [laughs]. So I don’t write it.

Actors are also trained to observe people. So I’m always watching and listening and if I hear a good line, I write it down and make sure it gets in a script. For example, the other day a friend and I were looking at places to eat and we found this one restaurant that had these delicious looking noodles and he said, “Mmm, my mouth is hard.” I thought that was so funny. So the next time I have two characters in a food situation, they’re not going to say, “Mmm, that looks delicious.” They’re going to say, “Mmm, my mouth is hard.”

CR: That works in a comedy, obviously. But what about when you’re writing M.F.A., which is about a campus rape? How do you keep the dialogue interesting when you can’t depend on humor?

LM: Good question. I try to subvert familiar situations when I can. The scene that everybody brings up in M.F.A. is when the lead character, who’s been raped, goes to a “Feminists on Campus” meeting hoping for support. But when she goes to this gathering, she doesn’t get this outpouring of emotion or comfort. Instead, the girls were like, “Oh my God. Hash Tag Feminsim!” “We should do a bake sale.” “Oh yeah, we should provide a nailpolish where if you stick your finger in a drink it shows you if it’s been drugged.” “Ooh, good idea!” So it goes against what the main character is looking for in the scene and what the audience is expecting from the scene.

CR: What do you think the difference is between good and bad dialogue?

LM: Bad dialogue is often too literal. Too robotic. It has too much information. What is that word called? I have this list of words I always have to check.

CR: Exposition?

LM: Exposition! I’m a writer. I swear. That’s the thing that kills me. When there’s too much exposition. When a writer is doing too much telling and not enough showing. I’m such a big believer in show don’t tell.

CR: What do you mean by that because if you’re showing, you’re not writing dialogue.

LM: For example, if someone is heartbroken, they shouldn’t say, “I’m heartbroken.” If she’s in the room with the guy who broke her heart, you want to focus on how she won’t make eye contact. Or the guy doesn’t make eye contact. That sort of thing. No character who’s in pain should ever have to say that they’re in pain. We should be able to feel that through their actions.

I have this writer friend I’ve been helping and his characters explain everrrryyyyyyyy-thing. I’ve told him you need to cut all of this waaaaaaaay down. What isn’t being said is far more interesting than what is being said. Humans rarely talk about their emotions. They avoid emotions.

CR: Not a lot of writers are blessed with a natural comedic ability but they’re still required, at times, to write comedic scenes. How does one write funny dialogue?

LM: I don’t know. I tend to go with “TMI.” The things that would be so awkward if you said them but you’re still thinking them? Having your character say those things has always been a guide for me. A lot of times my characters are sort of irreverent and say the wrong thing. They very rarely say the right thing. If you could’ve done it over, you would’ve said it better. But there’s so much humor in the person reaching for the right thing and coming up short. There’s this great quote: “Funny people are just really observant.” I think that’s true.

One of my favorite movies is Little Miss Sunshine and my favorite scene is when the main girl says, “Grandpa, am I pretty?” And he says, “You’re the most beautiful girl I’ve ever seen in my whole life, I’m completely in love with you. And it’s not because you’re intelligent, it’s not because you’re nice, it’s completely because you’re so beautiful.” And I love that so much because it’s a little inappropriate for a grandpa to say to his granddaughter. And you’re not supposed to tell a little girl that her heart and her intelligence do not matter. But it’s so true and so honest that that’s how he handled the question. That is the kind of s*#t I want to write.

CR: My favorite scene in Voicemails was the meet-cute scene between Jill and Tyler. What I noticed about that scene was that the characters rarely said what you expected them to. They always seemed to say the opposite of what they were supposed to say. How did you approach that scene?

LM: I’ve never told this to anybody. When I got to LA as an actress, I started writing things secretly. I didn’t know how to write a screenplay but I understood how to write a scene. So I would write these little scenes. And I had written that meet-cute scene during that time. It wasn’t inspired by anything other than my own life – moving to Hollywood. Trying to navigate the town. Anyway, many years later when I was writing Voicemails, I stumbled across that document with all the old scenes in it and I found that scene and I thought, “Hmm, that’s pretty good!” And I pasted it into Voicemails without changing a whole lot. But that was a real revelation for me because I realized, you might not know how to write a script, per se, but it doesn’t mean that you don’t know how to write or that you don’t have talent as a writer. It’s really validating to hear that that was your favorite scene cause that’s one of the first things I ever wrote.

But yeah, if I analyze why that scene works now, I think it’s because they’re pushing each other, testing each other, and that’s where the fun banter comes from.

CR: Any last dialogue tips you can give us? For that writer out there who never gets complimented on their dialogue?

LM: Hmmm. People don’t generally speak in complete sentences. It’s difficult for people to have complete thoughts in the moment. They stutter. They start making their point only to realize they’ve messed up and double back. They struggle to get to the point. They say very inappropriate things along the way. The big thing for me is the verbal diarrhea character. Their own honesty is a plague for them. If it’s comedy, I’d say honesty is your best friend. The uglier and grosser and more grotesque the answer is, the better. And if it’s a dramatic scene, have your characters struggle with their pain. Struggle to hide the truth. The elephant in the room is the true emotion. But they should play EVERY OTHER emotion before going to that one. It’s so much more interesting to watch a person try not to cry than to watch a person crying.

And if I could give one last piece of advice, I would encourage writers to not wait around for permission. Try to get your own stuff made. And I’m not just talking about getting a film made because I know films are expensive. But I did a 7 episode web series when no one would give me the time of day. I wrote six short films with parts for me as an actress. I always hustled and never waited around. I think that’s the reason for any success I’ve had. You can do the same. You can put two actors in a car with some green screen and shoot it on an iPhone for nothing. What’s your excuse? You can do it!

Is Chaos Walking as bad as the trades are making it out to be? Or is this Charlie Kaufman scripted adaptation secretly genius?

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: A boy and girl go on an adventure together in a world where everyone can hear each other’s thoughts.

About: The famed Chaos Walking!!! Based on the best-selling book. The movie that has been edited and re-edited, reshot, double reshot and triple reshot. The movie that Linosgate is determined to get right no matter what. Daisy Ridley joined the project, in large part, because she was a fan of the book. Tom Holland came on board once he learned that he’d be acting opposite Rey Kenobi. After recent reshoots that totaled 15 million dollars, the film is slated to come out at the beginning of next year.

Writer: Charlie Kaufman (based on the novel by Patrick Ness)

Details: 134 pages!

Chaos Walking is one of the most troubled productions in Lionsgate’s history. It’s just been, well, chaos. This despite the film having such a cool cast. Adding a bit of wackiness to the proceedings, one of the most original voices in the industry, Charlie Kaufman, was the first writer hired for the project.

He adapted Patrick Ness’s novel, who had an interesting inspiration for the story which he laid out in a Publisher’s Weekly interview: “I live in England so I take a lot of trains, and you can’t really go anywhere without somebody talking on their mobile phone behind you, forcing you to listen to their conversation. With the Internet, with texting, with networking sites, there’s already information everywhere. The next logical step is, what if you couldn’t get away? How difficult would it be if you could hear what everyone was thinking all of the time? And how much more difficult if you were a teenager, when your thoughts are tumultuous, when privacy is important? I thought this would be pretty awful. So that’s where it started, with the idea of information overload.”

Todd is going to be 13 soon and being 13 in this world makes you a man. What world is that? I have no idea. I thought it was earth at first but apparently there are two moons so unless a new moon showed up uninvited, I’m guessing this is an alien planet.

Speaking of, there’s something everybody experiences on this planet called “noise.” Not the noise you and I are accustomed to. The noise on this planet includes the thoughts of everything. People. Animals. Trees. If something is alive it gives off thoughts and you have to listen to them whether you want to or not. Sort of like if your annoying little sister never shut up. But she was a cactus.

Todd deals with this by talking a lot. To himself. To his stupid dog who he hates. To his foster dads. Todd talks A LOT. And he usually yells when he talks. I don’t know if he’s trying to do a Chris Farley impression or he’s doing it to drown out the noise.

But none of that matters when Father 1 comes up to him and tells him that everything he knows is a lie! That the Mayor of Prentisstown is evil and wants to do horrible things to Todd. That is why his mother left a diary with a map. Todd must go where the map tells him to go to find… I don’t know? Happiness maybe?

Luckily, he meets a girl, Viola, along the way. By the way, all the women on the planet have been killed by an alien virus. So finding a girl is a big deal. The girl doesn’t seem to be able to hear the “noise.” Nor can he hear her thoughts. And since she doesn’t talk much, she’s a big fat mystery to him.

The two head to the next town where Todd runs into more women. This is what solidifies that, yes, he’s been lied to A LOT. But why? Just as he asks that question, the town is attacked by the Prentisstown army. Todd and Viola (and the dog! ruff!) are forced to flee. They are now on a full-fledged Lord of the Rings level journey. Will they find what they’re looking for? I sure as heck hope so.

There are two ways to look at why this project has become such a headache for Lionsgate.

The first is that you adapted an unfilmable story. Just the act of having a constant stream of talking at all times during your movie is a recipe for disaster. That’s literally torture for an audience. And my guess is that that was the biggest issue in the infamously bad test screenings for the movie.

On top of that, you have this secondary “noise” of seeing imagery of things people have done in their past. So if you run into a guy who’s killed someone, you see an image of them killing that person. Combined with, maybe, them picking apples earlier that day. It’s not clear how these images appear. But I guess they show up right next to the person’s face like translucent video. From a movie-perspective that sounds disastrous. It just seems like it would look weird.

So you have something that’s potentially annoying combined with something that’s potentially silly present in the movie at all times – yeah, that sounds like the kind of thing that could cause bad test screenings.

The other way to look at this is that many of the best movies tried something that had never been done before. As weird as Chaos Walking is, the one thing I give it is that it’s trying something new. It really is trying to reinvent the language of cinema. Sort of like the way A Quiet Place played with silence, this is playing with noise.

Regardless of these ambitions, there should only have been one version of noise – sound. This is something I talk about all the time when writing sci-fi and fantasy. You don’t want to make the rules too expansive. That’s how you lose audiences. It’s literally called “noise.” It’s SOUND. Why are you adding a visual component?

How should I explain this? With every additional component of mythology you add, you are taking time away from other components. If you only have the one thing – that everybody hears each other – it’s easier for us to follow along and you can explore that one thing in as much detail as you want.

And hearing thoughts you’re not supposed to hear is full of dramatic possibilities. If that’s the only thing you have to figure out, you can make that work. It’s all the weird wonkiness that Ness added on top of that that’s thrown this story out of orbit.

Why do all women have to be dead??

Why are we on another planet?

Ugh! I get so angry when writers over-complicate things when they don’t have to. Cause that’s one of the quickest ways to tanking a story – over-complicating it. I know it’s tempting with this genre. You want to show us how imaginative you are. But resist the temptation! Keep it simple!

The funny thing is that when you listen to Ness talk about the book, it sounds great. He’s smart and he’s clearly thought all this through. But then you read it and it’s overly complicated and dumb. It’s not the disaster that the media made it out to be. But it still doesn’t work. It’ll be interesting to see what it’s become because they hired every big name writer in the business to come in and fix this thing. I think they really want it to work cause they know they have that killer cast combo of Tom Holland and Daisy Ridley.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Patrick Ness on how he crafted his villain, Mayor Prentiss – “I don’t like people who are just monsters. I think that lets us off the hook, because you think, well, I don’t have to worry about him because he’s just a monster and that’s not how a real human would act. I try to keep him as a man who through various circumstances simply went wrong. Basically, I like to believe that everyone can be redeemed. The potential for redemption has to be in everybody, otherwise there’s no hope for us. Now whether he wants to be redeemed, that’s a different question, but the possibility needs to be there. There’s still some humanity in him somewhere. I think that makes him more interesting as well, because a pure psychopath, a pure monster, is fun, but limited.”

What I learned 2: Ness did something really interesting in the book. He decided when he created Todd that Todd would never say a line of exposition. That he would only say what a real boy would say in that moment. That’s a great writing challenge. To write a main character who isn’t allowed to explain anything. Cause that’s where dialogue becomes the most stilted – when characters are forced to expose things.

Genre: Period/Supernatural

Premise: (from Black List) A young slave girl named Lena has telekinetic powers she cannot yet control on a plantation in the 1800s.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List. The writer, Sontenish Myers, an NYU grad, received the Tribeca Film Grant to make the film. The Tribeca Film Grant provides film budget grants for under-represented groups.

Writer: Sontenish Myers

Details: 114 pages

The other day I was talking to someone who is not in the screenwriting world. They like movies but they’re by no means obsessed with them like you and I are. Anyway, she was curious about my job, particularly when it came to deciphering the difference between a good script and a bad script.

“It’s all subjective, right?” She said.

This is not the first person I’ve run into who believed that the only difference between one script and another is the subjective nature of who reads it. The variable these people never consider is that a script must meet a basic standard of quality before it can be judged subjectively against other scripts. If it has not met that standard, then it is objectively not as good as other professional screenplays.

I don’t know if everyone here remembers Trajent Future and his bullet time dreams. But that classically bad amateur script was objectively worse than its professional brethren.

The question I then get is, how do you objectively know the difference between a beginner script and a professional script? Well, that answer is long and varied because there are a lot of things one must learn to write a professional-level script. But we’re going to go over a couple of ways to spot a problem script today to give you a feel for how readers assess these things. Let’s take a look.

The year is 1802 and 11 year old Lena is a slave on a cotton plantation with her mother, Alice. We learn early on that Lena can make things levitate. Like bottles or buckets of water. As a kid, she has fun with the power despite the fact that her mother keeps reminding her that if anybody finds out about this, they’re dead meat.

One day the decision is made to bring Lena inside and make her a house slave. So she and her mother are split up. Lena then tries to befriend all the other house slaves (all of whom are older) to mixed results. She also struggles to keep her telekinesis under control.

Then, one day, when she’s out getting water, a mysterious black woman approaches her and takes her back to her secret underground home. She’s seen Lena use her powers and wants to help her hone them. This interaction leads to the best exchange in the script. “Why do you live down here?” “Down here I’m free, up there I ain’t.” “Freedom is a lot smaller than I thought.”

In addition to Lena’s weekly telekinesis lessons, she also finds a 14 year old slave – Koi – who ran away from a neighboring plantation. Lena introduces Koi to the mysterious underground witch woman who feeds him and prepares him for his next journey.

After weeks of daily chores and strengthening friendships with the other house slaves, Lena’s worst nightmare comes true – her mother is sold. Lena slips away to Koi and the Telekinesis Witch and demands that they do something – use their powers to get her back. But will the two help Lena? Or do they consider the task too risky?

“Stampede” is an example of a common beginner concept mistake. A writer will give a character a power and believe that that power has given them their story. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work like that. Giving Lena telekinesis doesn’t give you a screenplay. All you’ve done is give your character a trait, not unlike the ability to play baseball or be a really good businesswoman. What about your story? What is going to happen that will make that trait interesting? That will put that trait to the test? Most beginner writers don’t know the difference between the two and therefore cobble together a disjointed narrative while occasionally going back to the power in the hopes that it will do some heavy story lifting.

Look at Get Out. The beginner screenwriter version of that is a black man dating a white woman. That’s it. The writer hasn’t thought beyond that. But the veteran screenwriter knows that all he’s done is set up the characters. He still has to come up with a story. So he adds that the girl is taking the boyfriend to meet her parents for the weekend and something bad is going on at their home. We never get anything like that in Stampede. It’s a narrative with no singular focus.

To be honest, I think this script would’ve been a thousand times better without telekinesis. The telekineses only serves to distract from the more poignant story about a young slave. It also makes the reader keep waiting for the telekinesis to become a bigger part of the story. And since it’s only a minor component, we never get that payoff. That makes the power a story distraction rather than a story ally.

Also, it seemed like there were better directions to take the story. But, in another common beginner mistake, the writer always took the path of least resistance – the path that made it easiest to write. You want to do the opposite. You want to go in those directions that are scary for you and harder on your character. If the slave owners would’ve discovered Lena’s powers, for example, maybe they try to use them for their own nefarious goals. Teaming up a slave and slave owners is where you’re going to find those messy but more interesting storylines.

But the biggest problem with the script is that the narrative isn’t purposeful. There is no goal. There are little, if any, stakes. And there’s definitely no urgency. Combined with the fact that the hero is stuck in one location, the story feels passive. There’s nothing for the characters to do. This leads to the writer coming up with all these small side stories, like the witch, like the 14 year old slave boy, like the friendships with the other slaves, that have no narrative thrust. There are no engines beneath these stories so whenever we’re participating in them, we’re asking ourselves what the point is.

How do you give a script narrative thrust? Simple. You create a big goal with high stakes attached. At around page 90 in this script, Lena’s mother gets bought by another slave owner and taken away. I’m not going go into some of the ancillary problems with this plot choice (we hadn’t seen the mom for 65 pages so we didn’t feel anything when she was sold). But what you could’ve done that would’ve been a lot better for the plot is to have the mother bought on page 25, the event that forces Lena to be moved into the house. Now you have a clear goal – Find and reunite with her mother again. It really is as simple as that. And that doesn’t mean you have to send her off on the journey. The entire movie can be her planning her escape and how she’s going to get to her mother and then the final act is her executing the plan.

Finally, you need your super-power to connect to your story better. Or else it just feels random. And that’s how this power felt. What does lifting bottles up have to do with anything in this subject matter? There’s literally zero connection – plot wise or theme wise. This tends to be another beginner mistake. The young screenwriter gets so hung up on the thing that they personally think is cool (in this case, telekinesis), that they never consider whether it’s relevant to the story they’re actually telling.

Last week, with The Paper Menagerie, the mother character had the power to make origami animals that came alive. That power had a ton to do with the story. It was cultural. It was the only way she knew how to connect with her son. They were a poor family so those animals were the only toys he had. They were also his only friends. And the animals ended up having messages within them that gave us our surprise ending. In other words, the power was organically connected to the story. We never got that here.

This script was just way too messy for me. I’m kinda shocked it made The Black List.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Period stories tend to work best when they’re set during a time of transition. All I could think while reading this was how much more intense it would’ve been had it been set in the months leading up to the end of slavery. The slave owners would’ve been more on edge. There’s uncertainty in the air. There’s more anger and, therefore, more potential for violence. This script was definitely missing an edge. That could’ve provided it.

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: An archeologist father and his young daughter must attempt to decipher an ancient alien message on a distant planet.

About: This is the big package that is bringing back a lot of the same team from “Arrival,” as this is another thinking man’s sci-fi story. The short story comes from Ken Liu. Shawn Levy of 21 Laps is the one who purchased it.

Writer: Ken Liu

Details: Short story about 15,000 words (an average screenplay is 22,000)

I’ve been all over Ken Liu since reading his amazing short story, The Paper Menagerie. When I heard he’d be teaming up with the new king of Hollywood, Shawn Levy, to adapt his short story, The Message, into a movie, I couldn’t remember any project announcement that got me more excited this year!

But one thing I’ve realized as I’ve studied Ken Liu is that he’s realllllyyyy smart. Intimidatingly so. Check out this answer he gave in a recent DunesJedi interview regarding his approach to science fiction versus fantasy…

“I think of all fiction as unified in prizing the logic of metaphors over the logic of persuasion. In this, so-called realist fiction isn’t particularly different from science fiction or fantasy or romance or any other genre. Indeed, often the speculative element in science fiction isn’t about science at all, but rather represents a literalization of some metaphor. I like to write stories in which the logic of metaphors takes primacy. My goal is to write stories that can be read at multiple levels, such that what is not said is as important as what is said, and the imperfect map of metaphors points to the terra incognita of an empathy with the universe.”

I’ll have to get a doctorate in Smartness at MeThinkGood University before I’m fully able to digest all of that. But the parts I did understand speak to one of the debates we’ll have later on. “The Message” has a lot of pressure on it as it’s coming after the perfection of The Paper Menagerie. Let’s see if it delivers.

Our story takes place in the way-off future. Our narrator, an exo-planet archeologist, flies around the galaxy to ancient civilizations in order to learn about extinct alien races. They’ve found a lot of these civilizations. But, so far, nobody has been able to find a LIVING alien race.

Just before he’s about to explore his latest planet, the narrator learns that his wife has died and he must now take care of their 11 year-old child, Maggie. He’s never even met Maggie so how do you say “awkward” in archeology-speak? Due to the fact that they’re going to blow up the latest ancient civilization planet soon, the narrator doesn’t have time to drop his daughter off and must bring her along.

Together, the two walk around the pyramid-infested city, which died off over 20,000 years ago. Their goal is to decipher “the message.” There are a lot of hieroglyphics everywhere and he’s convinced they’re all trying to say something. With the help of Maggie, who’s also into archeology, they do their best to decipher all the mysterious pictures.

Meanwhile, Maggie passive-aggressively needles her father about prioritizing his work over staying with the family and raising her. Why the heck does he care more about long-dead alien civilizations than his own family?? It’s a good question that takes a back seat when the dad finally cracks the message (spoiler). The message is that this is a highly radioactive area. Stay away. Stay away. Stay away.

This means they are both dying quickly. The dad can put Maggie in stasis which will halt the radiation poisoning until they get her to a hospital. But since the ship was damaged during landing, the dad will need to manually fly it back up into the atmosphere. By that point, the radiation poisoning will have reached a point of no return. He’ll die. Which means that just as this father-daughter relationship was about to get started, it’s already over. The End.

You would think ancient alien civilizations would be ripe subject matter for a movie. A sweeping shot of the long dead alien city alone is a money shot for your trailer. And yet the last two Alien movies proved that maybe ancient alien civilizations aren’t as cool as we thought they were. And this latest dive into the subject matter isn’t giving me a lot of confidence that that trend won’t continue.

Then again, Liu always seems to be more interested in the human element of these stories than he does the science element. If the character stuff works, it’s going to make the ancient civilization plot work by proxy. Unfortunately, the character stuff doesn’t work. Which is surprising considering that Liu wrote such a great parent-child storyline in The Paper Menagerie.

Today’s story proves that there’s a razor thin line between emotional effectiveness and melodrama. When the emotional component is working, it’s like magic. Our stories seem to come alive right from under our fingertips. When it’s not, it’s frustrating because you’re never completely sure why. It *should* work. A dad and the daughter he’s never met before are forced to team up to solve a puzzle. She doesn’t like him. He doesn’t understand her. The subtext writes itself.

However, something about this relationship feels on-the-nose compared to Menagerie and therefore never connects with the reader. I think I know why. If you look at The Paper Menagerie, the mother-son relationship was built around a very specific issue – she refused to speak English. He refused to speak Chinese. The story was about lack of communication. It was specific.

The Message doesn’t have that. There isn’t a specific problem in their relationship. It’s general. He ran off on his family so this is the first time they’re together. General is derived from the same tree as Generic. When you generalize in storytelling, you are often being generic. That’s what this felt like. Your average generic daddy who has to take care of a daughter he never knew he had story. Hollywood comes out with five of these a year. So if you don’t work to specify the relationship in some way, like Liu did with Paper Menagerie, the story is never going to take off.

More importantly, the emotional beats aren’t going to have the same oomph. This is why it’s so easy to shoot for a big emotional scene only to have the reader rolling their eyes.

Getting back to what Liu was talking about in that interview, he says that fictional writing should be all about the metaphors. I’m not sure I’ve heard an author say that before. I suppose it could be a short story thing. But I got the impression he was talking about all fiction. I vehemently disagree with that approach.

I got the sense that this ancient civilization had a metaphorical connection with the dad’s fractured relationship with his daughter. But I couldn’t make out what that connection was. Maybe someone can help me out. But even if I did understand the metaphor, it would not have made me connect with these characters any better. It would not have fixed the fact that the plot is basically two people walking around an empty city the entire time. Those are genuine story weaknesses that could’ve been improved if the focus was more on the storytelling and less focused on metaphor.

I’ll go to my grave saying that telling a good story should be the priority of every script you write. If you want to win new friends in your English class, go metaphor-crazy. But if you want to write a story that people actually enjoy, focus on the storytelling. Drama. Suspense. Irony. Unresolved Conflict. Problems. Goals. Obstacles. Stakes. Inner transformation. Urgency. And here’s the catch. You have to do all of these things IN A WAY THAT’S NOT DERIVATIVE. The story, along with the elements within the story, have to feel fresh and specific. The Message didn’t pass that test.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Work vs. Family is one of the most powerful character flaws available to writers. This is because it’s such a universal flaw that everyone understands. Even if you don’t yourself have the flaw, chances are there’s someone close to you who does. Which means you understand it. That’s what you’re looking for with character flaws. You’re trying to find flaws that all human beings can relate to. Here, the father chose work over raising his child. Liu didn’t nail the execution (in my opinion) but I still see this character flaw working in a lot of stories. I know writers often struggle to find a flaw for their main character. Well, this one is one of the easier flaws to show and execute as a character arc. So keep it in the hopper.