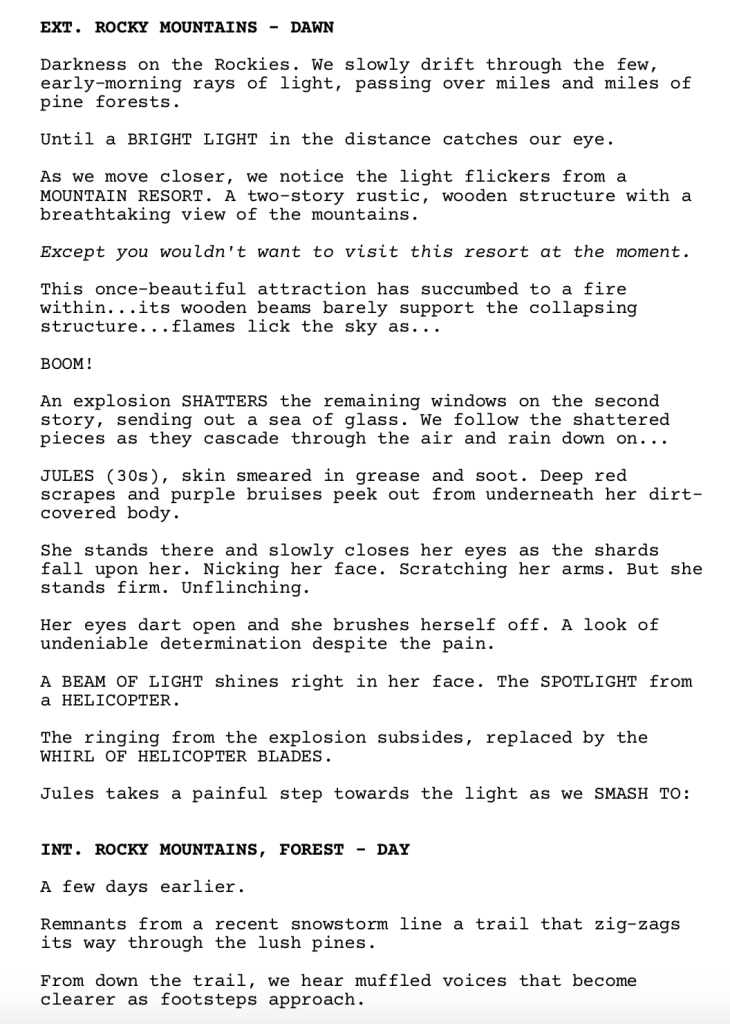

Genre: Creature Horror

Premise: Trapped in a mountain resort by a parasitic fungus that transforms its victims into deadly hosts, a timid CDC epidemiologist must learn to lead the group of mismatched survivors to escape this primordial terror.

Why You Should Read: After my last entry on the site, “The Crooked Tree,” was selected for a previous Amateur Showdown, I received invaluable feedback from the readers that I applied to my latest effort, “Genesis,” which explores the consequences of genetically-altering Mother Nature. Drawing inspiration from a slew of 80s classics, my career as a Registered Nurse, and a few real-life scientific oddities, I crafted a unique creature-feature that serves as my love letter to this subgenre. I hope my entry impresses you enough to select it for a coveted spot in this year’s Halloween Showdown!

Writer: Samuel Kerr

Details: 84 pages

Welcome mummies, tarantulas, and ghoulettes.

Carson isn’t in today.

Sorry, not sorry.

Your review will be written by me, Vampire Carson.

Ooh ooh ah ah ahhhhhh!!!!!!!

I know you’ve been waiting all year to suck the blood of the Halloween Amateur Showdown winner. Your moment has arrived. After doing some repairs on my coffin (note to fellow vampires: stay away from the Bedson 1000 – the sunlight blocking is dreadful and customer support is horrid) and retouching my windows with fresh black paint, I made a call to my best friend, Count In-and-Outcula, who promptly door-dashed me their Halloween special: Four double-doubles vampire style – extra rare beef on a plate of nothing.

After wolfing down this most monstrous meal, I poured myself a tall glass of Kevin Who Lived Downstairs, November 2018 (it’s wine-o-clock somewhere, amiright?) and opened my laptopula to read today’s winning entry. I’ve never read a screenplay before so let’s just say I’m dying to see what it’s all about.

Somewhere in the Rocky Mountains, a giant greenhouse is being burned to the ground with scientists inside! That’s because some sort of deadly virus broke out here. Cut to 30 years later where a couple of stoners, Beav and Moss, are poking around the remnants of this place and encounter a mushroom that blows up in a puff of smoke, right in Moss’s face.

Cut to a thousand miles away where Jules, a mycologist (a person who studies fungi) is trying to tame her special needs son. Then David, a field investigator for cases that involve epidemiology, shows up at Jules’s place and says he needs her for a job. Jules is reluctant because these two have a history, but when David’s boss says he’ll pay for Jules’s son’s private school if she goes, she’s all in.

They fly to a mountain resort so remote that helicopter is the only way in or out. The two arrive to meet Martha, the owner of the resort, who’s accompanied by her special needs adult son, Ace. Ace doesn’t like messes. Jules goes up to check on the incapacitated Moss’s infection and it’s not looking good, folks. The guy has a distended stomach that makes him look pregnant.

Meanwhile, David recruits Beav to join him at the scene of the crime. There they find one of the original dead scientists and decide to throw him in a bag and drag him back to the resort. After all that work, it’s time for dinner! While everyone digs into some chicken, Moss comes downstairs, hungry as a horse. After devouring everything he can find, something in his stomach starts moving. Moments later his abdomen bursts and a 2 foot slug slithers out, disappearing into the next room.

Jules is starting to notice something we noticed, oh, about 30 pages ago, which is that all of this feels very unprofessional. When she confronts David, he confesses that this is a private job. Nobody else knows about it but them. Jules is angry but they’ve got bigger slugs to fry. Literally. Cause the next time they see the slug, it’s four feet tall and has a circular face that opens up to reveal a thousand teeth.

Lucky for Jules, Ace is a bit of an engineer, and has managed to cobble together a makeshift flame-thrower. They’re going to need it. Cause Sluggy the Dental Anomaly is downstairs laying more mushrooms than were consumed at last year’s Burning Man. After creeping around the resort all night trying to kill or capture this thing, David’s boss shows up. And he isn’t happy with David. We know that because he shoots him 50 times. Jules and Ace are going to be next unless they can defeat both David… and the Mushroom Slug From Hell.

Guys!

Oh my god, I am SOOOOO sorry. I just got home from lukewarm yoga to find Vampire Carson reading this script. I did not give him permission to do this so I apologize for the inconvenience. You have to understand that October is Vampire Carson’s favorite month so he’s always in party mode. I remember we were hanging out last Halloween and my best friend, Kevin, was over. We had a night to remember. Then the next day Kevin just disappeared. Never wanted to hang out again. He didn’t even text, jerk.

Anyway.

The good news is that Vampire Carson took meticulous notes which will allow me to give you a proper review. I mean check these out (page 1: needs more blood, page 8: needs more blood, page 15: needs more blood, page 37: blood, needs more of it, page 52: lots of blood but not enough description of it). Why would I need to read a script when I’ve got notes like that? Let’s jump into it.

Scripts based on 80s creature features are surprisingly challenging to review. These movies tend to embrace a lack of realism that, when done well, actually enhance the viewing experience. But as scripts, they often seem cliche and unrealistic. Is that the intention or does the script really have problems? Depends on who you talk to.

Well, you’re talking to me. So here’s how I saw it.

There was something too “save the caty” about this story. The way the characters were introduced and the structure used were too common and predictable. We get the scary teaser scene of the greenhouse structure being burned down. We get the save the cat moment with our hero. She’s got a special needs kid to ensure we’ll like her. The opposite sex co-star shows up. They have a romantic history with each other but now don’t like one another.

Don’t get me wrong. I like a solidly structured screenplay, even if it hits all the pre-arranged beats. But when EVERYTHING about the script is familiar, it ceases to function as an original story. Instead, it becomes an homage on steroids.

And this is definitely that. I mean we have an alien creature that gestates inside the human body, spits out, then, over a very fast period of time, grows bigger, more complex, and more dangerous. We also have a female heroine running around with a flamethrower. Does that sound like any movie you’ve seen before?

I don’t want to rain on Sam’s parade because I did like the fungi angle. I’ve never seen that before. But Sam didn’t do anything with it. The mushrooms seemed to be a placeholder to get the alien inside a body, where it then became nothing like a mushroom. It could’ve come from anything. I would’ve spent more time designing a creature that felt like it evolved from mushrooms/fungi. Make this creature your own. When I saw the circular teeth, I thought, “I see that in every movie now. It was just in Men in Black.”

I also had a problem with the blasé approach to the investigation. I know that later we find out why (because this investigation is not official). But even if it isn’t official, you don’t let the guy who was just upstairs, bleeding profusely everywhere on his body and displaying vitals that say he should be dead, to casually come down and join you for dinner. This is a virus, is it not? Yet you’re asking him to pass the chicken?

The thing is, there might still be a movie here. I like the location. I like the unique qualities that a mushroom could have on a creature design. But I would come in here with a real team of scientists. I would cover the investigation much more realistically. And I would spend more time figuring out how an alien that grows out of fungi would look and operate. Cause if you put some real effort into this, it could be cool.

What did you guys think?

Script link: Genesis (new draft)

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you have one of your characters read an e-mail or letter, the audience rarely needs to know the whole thing. In a SCREENPLAY you’re always looking to convey the most amount of information in the least amount of words. So what Sam does here is the smart way to go…

Sorry, Vampire Carson insisted he get his own ‘What I learned.’ So here it is.

What I learned (Vampire Carson): When introducing characters, it is imperative you describe their neck. You can learn so much about a person from their neck. A long neck represents a confident individual. Short and stubby necks denote weak blood flow and therefore people not worth late night party invitations. Pale necks allow one to see veins easier, which is important for…certain people to know. Never overlook the neck.

I was SO BORED by yesterday’s script that I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it. Not just about how bad the script was. But the bigger question of: what is it that makes a script boring in the first place? If we could figure that out, we’d all be millionaires. Because the large majority of scripts are boring as s%$#.

There are a lot of factors that go into a script being boring. If your main character is boring, for example, it’s nearly impossible to make the script entertaining. But as I began to think through all of my favorite movies, one of the things that kept popping up was that the characters were always pushing us forward in some way. Now I know this is common advice but I don’t think people get into the details of why this is important or what it actually means. So that’s what I want to explore today.

I was reading an action script Saturday that was really good. And one thing I noticed was that the characters were always racing towards the next scene. Every scene, the hero had a clear physical goal they were after. And I thought to myself, “This is the secret! As long as you have a physical goal in every scene, your characters will always be moving forward. The script will always remain active.”

But then the obvious hit me: Not every script is an action script. And I’ve read plenty of non-action scripts that I liked. Heck, one of my favorite movies of the year is Parasite, and it’s 95% talking scenes. So what is it that they’re doing that keeps me just as interested despite the fact that the characters aren’t always racing towards a goal?

The answer came to me as I was reading another, more talky, character-driven script. In an early scene, two characters were talking while watching TV, and I was bored out of my mind. It wasn’t hard to figure out why. People watching TV is a passive experience. Sure, they’re talking to each other while watching the show and we’re getting some insight into their relationship. But as a scene, it was boring.

What I learned in that moment was that in addition to not being after anything physical in the scene, the characters weren’t VERBALLY after anything either. Neither character wanted anything out of this conversation. It was more a passive exchange of thoughts and information. And that’s when it became clear to me. In talky genres (drama, comedy, slow-burn thrillers, horror), your talky scenes should substitute PHYSICAL GOALS for VERBAL ONES. That way, the scenes still feel like they have a purpose.

A way to accomplish this in this scene is to have your HERO walk into the room with a goal. Let’s say he wants to borrow his roommate’s car so he can go on a date tonight. But the roommate is obsessed with his car so it’s going to be tough to convince him. Now, you have the exact same scene – two people talking while watching TV – but the scene has a new energy behind it because a character actually wants something.

Now let me make something clear. There’s no law that says passive scenes never work. I know, for example, that if you put great characters in a passive scene, it might be entertaining solely because we like listening to these characters talk. Their chemistry is entertaining all by itself. But I can tell you this. If you do this consistently throughout your script, your screenplay will be boring.

There’s a major pitfall in this approach that writers often get wrong. They assume achieving THEIR GOAL is the same thing as a character GOING AFTER THEIR GOAL. Let me explain. In the roommate scene I mentioned above, the writer may have thought, “I need a scene to establish the relationship between these two roommates.” That’s THE WRITER’S GOAL. So they write a scene where the roommates have a conversation, after which they go their separate ways. The writer believes he’s just written a good scene because he’s achieved HIS GOAL. And yes, the reader does have a better feel for the roommates’ relationship. The problem is, the writer forgot about the CHARACTER’S GOAL. And that’s the priority in every scene. Not what you need to do to make your story work. That should always be secondary to what the characters need to do to keep the story moving.

Let’s dig a little deeper into this because it’s important. It can be hard to figure out a goal in a scene if it isn’t physical. When you’re writing Guardians of the Galaxy and they head into Liplip’s Lair, it’s super clear what needs to happen – they need to retrieve the Idol of Blargorg. That’s a physical goal.

But let’s say that scene is over and Peter Quill is hanging around with his buddies in the ship. There’s no more Idol of Blargorg to retrieve so what is the scene about? An inexperienced screenwriter will think, “This is the time when I just have a lot of funny dialogue between the Guardians.” Hopefully, since you’ve started reading this article, you know this is the wrong way to go. We need a goal.

To give talking scenes a goal, you can utilize one of four options. Your hero has an overt goal. Another character in the scene has an overt goal. Your hero has a hidden goal. Another character in the scene has a hidden goal. Sticking with our Guardians example, we’ll give Peter Quill the goal and we’ll make it overt. “We need to go confront Thanos now.” Peter’s goal is to convince everyone to go confront Thanos. Nobody else thinks this is a good idea. So Peter has to make his case. And that’s how you write a scene with purpose.

You could also give Peter this goal but make it hidden. He wants to confront Thanos but he knows if he says so out loud, nobody will go for it. So instead, he’s trying to steer the conversation in that direction and help the others come to that conclusion. Rocket Raccoon says, “We should head back to the prison… recruit some more soldiers.” Peter replies, “Yeah but aren’t we just spinning our wheels if we do that. Shouldn’t we be focusing on tackling the actual problem?” Gamorrah chimes in. “I know a few people in Corchoran City.” “Yeah,” Peter replies, “but we’re running out of time.”

My dialogue is pretty bad there but the important thing is that Peter HAS A GOAL. What you’re trying to avoid is a character who doesn’t have any objective in the scene at all. As long as he has a goal, whether he’s keeping it to himself or not, we feel like the scene is HEADED SOMEWHERE. If a scene in your script feels dead, it’s likely because you don’t have this simple structural hack in place.

Now the nice thing about movies is your hero doesn’t always have to have the goal as long as someone else in the scene has the goal. A bad guy robbing a bank drags our protagonist bank manager to the vault and demands to know the code. Our hero doesn’t have the goal in this scene but the scene is still entertaining because SOMEONE has a goal.

Some of the most powerful scenes in cinema are when both characters in a scene want a goal badly. This is one of the reasons Silence of the Lambs is such a great movie. Clarice goes into every scene with Hannibal desperate for a new clue (her goal). But Hannibal never gives it to her unless she gives him something first (his goal). When you feel that amazing tension – that charge – when you watch these two in a scene? That’s where it’s coming from.

You’ll also notice that scenes play better the more that’s at stake. You could certainly write a scene where one character wants bubblegum from another. Technically there’s a goal. It might even be interesting if the other character only has one piece left. He may say, “What are you going to give me for it?” And now you’ve got some conflict to build your scene around. But that scene is never going to play as strongly as Clarice needing clues from Hannibal Lecter because Clarice needs those clues to save a woman’s life. The stakes are much higher.

All of this is to say that BOREDOM is often the result of a series of scenes where nobody wants anything. The writer has put THEIR STORY GOALS above CHARACTER GOALS. And so it seems to them like they’re achieving something. But in reality, the reader is getting a bunch of filler which allows the writer to take them from one plot beat to the next.

If you’ve ever felt like your script (or parts of your script) is boring or slow or “dead” or doesn’t have enough pop – go through every one of your scenes with this article in mind. Chances are, there are large chunks of your script where characters don’t have any goals.

Hope this helps!

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again.

This is the single most important Star Wars trailer of all time.

The Star Wars brand was destroyed in the hands of Rian Johnson. Everyone knows it now. Only a few Twitter users on an island try to make the case that it “wasn’t that bad.” Ever since The Last Jedi, the franchise has been stumbling. Solo bombed. An entire trilogy was canceled (Rian Johnson’s). Another one is close to being canceled (Benioff and Weiss). You’ve got Kevin Feige throwing around Star Wars ideas now, as if they’re so desperate for good press they’ll force their way-too-busy Marvel president to make a flick.

And that’s the thing. This trailer doesn’t just have to end the 9 film nerfology. It has to whet the appetite for Star Wars films moving forward. As much as we’ve heard Star Wars is eager to move away from the Skywalker Saga, the truth is, it’s still its best moneymaker. After this, you have to create all new iconic characters that people will want to watch through multiple movies. And if anybody thinks that’s easy, they’ve never written a screenplay before.

To achieve this feat, the Episode 9 trailer needed to be one of the most memorable trailers of all time. That’s not hyperbole. They’re hoping Rise of Skywalker will make 2 billion plus at the box office. To do that, you need to “Star Destroyer level” blow us away. You need to give us moments or shots where we seriously consider putting ourselves in an induced coma so we can get to opening day faster. Now that the trailer is FINALLY out, we have the answers we’ve been looking for.

How did it go?

First, let me share my immediate observations.

The opening shot with the training cap dropped is made to look like it’s Rey. I don’t think it’s Rey and I’ll leave it at that.

The choice of voice over is interesting. I’m not clear on who that is. Is it Poe? I’m sure everyone in the world will know by the time I post this so I’ll accept looking like an idiot. Still, the voice over had a crisper cleaner feel to it compared to previous voice overs, which I found refreshing. Anything to update this dusty franchise!

The first good shot is of the Resistance packed into a room with Lando at the center. I really liked that. Unfortunately, it was followed by an unnecessary shot of Rose which is only there because SJWs start whining on Twitter whenever the Star Wars brand doesn’t feature her.

Next we get the best shot of the trailer – when Kylo emerges from the water with his lightsaber. The shot is turbo-charged by the fact that he’s the only remaining character from the new trilogy who stirs up any emotion in us.

The Emperor segment where we see his chair and we see his ship rise from underground (or is that water?) is pretty cool. I’m into the Emperor returning. I know some people think it’s stupid but due to the Rianator killing off the big baddie in Episode 8 for all of 5 seconds of audience shock, JJ didn’t have a choice. I suppose you could’ve created a new villain. Or maybe matured Kylo into something way worse. But as long as his return makes sense, I’m down with it.

I liked the dolly shot of them running down the corridor. This is where JJ reminds me of a modern day Lucas. He still captures the essence of Star Wars, but adds something a little modern with that fast backwards dolly, a shot Lucas wouldn’t have thought of.

Space horses running on Star Destroyers. Hmmm… Not sure how I feel about this yet. I’d want to know more about the space horses. If you set up their properties as being specifically proficient for fighting in space, I suppose I could get into it. But you’re playing with fire cause if it goes wrong, you end up in Finn and Rose Tico territory where they’re racing those Harry Potter creatures into the wild.

I want to know what Rey and Kylo shatter into a million pieces. It looked like a Vader statue? I don’t know. But I want to know!

There are too many Star Destroyers and too many Rebel ships. When it becomes that many, they no longer seem important. And then, that over-the-shoulder Emperor shot is intriguing because it looks like some sort of mechanical device is moving him. Me like.

The final shot is Rey with her lightsaber and Luke and Leia saying “the force is with you.” Something tells me… and I’m totally guessing here. I don’t have any idea if this is true. That Rey might be a clone of Leia. But that would mean she’s a clone of Luke too, since they’re twins. Hmm… I don’t know. But I feel like we’re going to get one last big twist. If JJ is really going to pay homage to the franchise with this last film, he’d put a shocking personal twist in there somewhere. We’ll see.

So what did I think?

How do I put this.

The trailer isn’t bad. But it takes the wrong approach. This trailer needed to get us excited. Instead, it tried to tug at our heartstrings. C-3PO saying bye to his friends, for example – that moment is trying so hard to tease our tears. In theory, this is the right thing to do. If you can make people feel something, they’re more likely to hook than if you’re giving them a bunch of great shots.

But that assumes you have the emotional pieces to back that up. For emotion to work, it must be genuine. It can’t just be music and Star Wars shots. Case in point, the C-3PO shot I mentioned. He gets all emotional saying bye to his friends yet he doesn’t even know these people. He met them a few weeks ago. So the emotion is false.

JJ would’ve done better to put everything on the table. I heard somebody talking about how awesome it would be if the trailer showed the Emperor open up a lightsaber and then the camera pans over to see Luke Skywalker open up his lightsaber. I don’t think that’s in the movie. But those are the kinds of shots they needed to show here.

The reason we might not be getting them is because JJ doesn’t like to show anything past the first act in his trailers. He’s all about surprising the audience. So I think all this stuff happens in the first act (minus that Emperor shot). The rest of the film is being saved for the movie. Which means they’re overestimating our interest. People are not going into this with the same kind of enthusiasm they’ve had in the past. If anything, they’re going in skeptically. And so not using every single shot at your disposal is like throwing Lebron James in a game and telling him he can only shoot left-handed.

My biggest concern is that the trailer doesn’t have that WOW SHOT. A great trailer has to have that one shot that sells the movie all by itself. The moment Darth Maul opens up his two-sided lightsaber, for example.

This doesn’t have that. The trailer goes all in on Rey. And while Rey has some cachet as a Star Wars character, if you were to rank every Star Wars character in popularity, she’d be lucky to end up in the top 25.

I understand why JJ did this. It’s not like you can start over again. But one of the issues Rian Johnson was too ignorant to recognize was that when he made Rey a nobody, he took a character who was already average-at-best and made her even less interesting. If Rey’s not connected to this lineage, if she’s just some random outsider, why do we care what happens to her? This is the SKYWALKER SAGA.

There are Rian Truthers out there who will tell you, “It’s good that she’s a nobody,” and tout reasons like, “That means anybody can be a Jedi!” But every real Star Wars fan knows these people are wrong. You took a character who needed a PR makeover in the second film to offset the Mary Sue criticism, and you instead made her even less important. It’s kind of baffling, to be honest.

Now maybe JJ does make Rey’s lineage relevant to the story, slamming Johnson’s dumb idea into the wall and shattering it just like Johnson slammed JJ’s Kylo helmet into the wall to shatter it. If he can do that and it MAKES SENSE? I’ll be thrilled. But there’s nothing in this trailer that gives me hope this will be anything other than an average film. And you know what? Maybe that’s a good thing. Now I’ll go into the movie with super low expectations, which will make it easier to enjoy.

What did you think?

Parasite is the best Korean film ever!!! And yes, I’ve seen Oldboy.

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: A poor family slowly and methodically infiltrates a rich family’s home by taking all of the help jobs.

About: Even though Parasite had a 99% RT score, I was still skeptical. I mean how much can we really trust a website that gives Black Panther a 97% score? But the reviews coming out of Parasite seemed to have some extra bite to them. They weren’t the usual hyperbole-laden suspects attempting to get quoted in the movie’s trailers. The people who saw the film genuinely seemed bowled over by it. The film originally made headlines when it won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and then later when it debuted to a limited release weekend and sold out every single seat of every single showing. The film comes from one of Korea’s most popular directors, Bong Joon-Ho, who’s directed such films as Okja, Snowpiercer, and The Host. Here, he collaborated with first-time screenwriter, Jin Won Han.

Writer: Jin Won Han and Bong Joon-Ho

Details: 136 minutes

I was CON-VINCED I was going to hate this movie.

Korean cinema has always been a wildcard for me due to its wildly shifting tones and mid-movie genre-jumping. Often the movies lose themselves inside a rambling unclear narrative.

So I was more surprised than anyone when I didn’t just like the movie, but loved it. How did a Korean movie win me over for the first time since Oldboy? Read on to find out!

Parasite follows a poor Korean family, two parents in their 50s, a daughter, and a son, both just north of 18, who live inside a cramped basement apartment. They’re reminded every day of their lot in life when a homeless drunk comes by and pees in front of their place.

One day the son, Kim Ki-woo, gets a unique job opportunity to tutor a rich high school girl in English. He heads across town to the family’s stunning home, built by South Korea’s version of Frank Lloyd Wright, who sold the house to the family a few years ago.

Kim Ki-woo wins over the mother quickly, and is soon wrapped up in a romantic relationship with the daughter. When Kim Ki-woo hears that the mother is looking for a private art teacher for her young son, he suggests a brilliant young teacher he knows. Except Kim Ki-woo doesn’t know any art teachers. Instead he brings in his sister, Kim Ki-jung, who soon has their young son wrapped around her finger.

One night, when the rich family’s driver is taking Kim Ki-jung home, she slips off her underwear and purposefully places them below the back seat. The next day, the rich father spots them, assumes his driver is using his car for recreational purposes, and fires him. Not to worry, Kim Ki-jung tells the father. I know an amazing driver. One of the best in Korea. And that’s how their father, Kim Ki-taek, secretly becomes the driver of the family.

The final obstacle is the housekeeper, which is going to be tough. She came with the house itself, the architect’s former employee. So the family finds out she’s allergic to peach fuzz and starts covertly pouring it on her whenever they walk by, causing the housekeeper to become a walking health hazard. Worried that she’ll infect their kids, the parents fire her, and, oh, what do you know, Kim Ki-taek knows one of the best housekeepers in Korea.

The poor family, now firmly entrenched in the household, ruminate on what’s next. But then one night, when the rich family has left town, the former housekeeper comes back and asks if she can collect something she forgot. The mother, Kim Chung-sook, reluctantly lets her in, and the housekeeper goes straight to the basement where she slides open a giant cabinet to reveal a secret door.

At this point, the housekeeper does not know that this family is connected. She believes they are all separate people, just like the rich family. So the rest of the poor family hides while Kim Chung-sook follows the housekeeper into the secret basement space. It’s there where we find a crazed man living down there.

It’s the housekeeper’s husband, who she’s been hiding here ever since the architect was in the house. When the rest of Kim Chung-sook’s family accidentally spills out into the basement, the housekeeper puts it all together – they’ve conned the rich family. This means she now has the power. And once the poor family realizes this, they must decide how far they want to go to keep this house (of cards) they’ve built.

One of my gripes with any film that originates outside of America and the UK is the bad screenwriting. They don’t put much emphasis on screenwriting in other countries, which is why you’ll see a bunch of movies that look amazing but are narratively unsatisfying. People simply don’t know how to properly tell a story. And you can make all the arguments you want about their version of storytelling being “different,” but the reality is, most of them are stumbling around with the lights off hoping to make it to the exit.

By comparison, this screenplay is EXTREMELY WELL-WRITTEN. One of the ways I can tell that writers have given a script their all is setups and payoffs. Anybody can write a couple of setups and payoffs in a script. But it’s when you see them again and again and again that you know the script took planning.

The famous architect for example. They made that clear early on. They also made clear that the housekeeper worked for him before she worked for this family. For this reason, when the script’s riskiest plot development is revealed – the secret doorway that leads to the housekeeper’s husband living in a hidden room – we don’t question it. We know this architect is famous and would conceivably build a hidden room in his house. And because it’s been made clear that the housekeeper used to work for him, we buy that he’s been hiding here for the better part of four years.

But it wasn’t just the big setups and payoffs, it was the little ones. They establish early on through several show-don’t-tell scenes that the sister, Kim Ki-jung, is artistically talented. So we don’t question it when the rich family is looking for an art tutor that Kim Ki-woo would call upon his sister. Ditto the dad. We establish that he used to be a driver before we introduce the plot point that the rich family needs a driver.

All of this may seem obvious in retrospect. But trust me, I read all the scripts where the writers don’t set things up. In the sloppy version of this, the father is never set up as a driver. The poor family would say, “Dad, you can drive, right? We’ll make you the driver.” That reeks of “come up with the idea on the spot.” Setups and payoffs allow you to create seamless stories that are eloquently crafted.

And the structure is great here as well. The mid-point twist (an event that happens at the midpoint of your story that sends it in a different direction so it doesn’t feel the same as the first half of the movie) is one of the best I’ve seen in awhile, that being the reveal of the secret door. To say that it changes the feel of the film is an understatement. The first half of the movie takes place over a few months. The second half takes place over one night.

The script also has a traditional “lowest point” moment. The “lowest point” occurs at the end of the second act (between pages 80-90). The idea is that you bring your characters down to their lowest place. Achieving their goal looks impossible. This brings the audience’s mood to an emotional low as well. In Parasite, the family does get out of the house that night, but they come home in a storm only to realize that their entire place is flooded. Everything is lost.

The reason you bring the audience down is to make the climb back up as high as possible. As in, the climb-max. You’re going to climb their emotions ALL THE WAY UP to your final scene, which should be the emotional high of the movie. And Parasite has one of the most memorable climaxes you’re ever going to see. That I can promise you.

All in all, this wasn’t just a great movie. It was a great screenplay. And that’s why I loved it. I know I’m going to catch some flak about that Oldboy statement. But I stand by it. That’s how good this movie is. Usually, I’d say wait for streaming for a character-centric film. But not this one. Go out and see it as soon as possible.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[xx] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A midpoint twist shouldn’t just change the story to change it. The change should add an exciting dramatic element. That’s what Parasite does. The reveal of the secret underground living space ramps the movie up into thriller territory. The rich family comes home earlier than expected, forcing the poor family to dispose of the housekeeper and crazy husband quickly. They then get stuck in the house with the family home and must figure a way out before the night is over. That’s an exciting dramatically compelling situation.

First of all, I want to thank everyone who sent a submission in for Halloween Amateur Showdown. I got a lot more submssions than I thought I would.

BUT!!!

I have to take a moment to plug my logline service (e-mail me at Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “logline” for a consult). So many of these submissions shot themselves in the foot due to terrible loglines with fixable issues. If you’ve never received instruction on how to properly write a logline, you should seriously consider a consult. The basic option is just $25 and the deluxe is $40. And, trust me, you’ll have a much better feel for how to properly write a logline after you get one.

Moving on. I tried to vary the TYPES of horror scripts as much as possible. That way we didn’t get 5 contained horror movies. So that may have been why your script didn’t get chosen. Other reasons your script didn’t get picked: There were a lot of loglines that weren’t clear. Some that were too outlandish. Some that sounded so simplistic I thought they were a joke (“A man believes he’s living in a haunted house and recruits his family to help him”). Some that were embarrassingly general (“A group of friends head out to a remote setting and, fearing an unspeakable evil, prepare to face it while also battling demons within.”). Some that sounded too similar to recent entries. And some that may have appealed to others but simply weren’t my jam.

What follows are the pitches that rose to the top.

Amateur Showdown is a single weekend tournament where the scripts have been vetted from a pile of hundreds to be featured here, for your entertainment. It’s up to you to read as much of each script as you can, then vote for your favorite in the comments section. Whoever receives the most votes by Sunday 11:59pm Pacific Time gets a review next Friday.

Got a great script that you believe can pummel four fellow amateurs? Send a PDF to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the title, genre, logline, and why you think your script should get a shot.

Title: Genesis

Genre: Creature Horror

Logline: Trapped in a mountain resort by a parasitic fungus that transforms its victims into deadly hosts, a timid CDC epidemiologist must learn to lead the group of mismatched survivors to escape this primordial terror.

Why You Should Read: After my last entry on the site, “The Crooked Tree,” was selected for a previous Amateur Showdown, I received invaluable feedback from the readers that I applied to my latest effort, “Genesis,” which explores the consequences of genetically-altering Mother Nature. Drawing inspiration from a slew of 80s classics, my career as a Registered Nurse, and a few real-life scientific oddities, I crafted a unique creature-feature that serves as my love letter to this subgenre. I hope my entry impresses you enough to select it for a coveted spot in this year’s Halloween Showdown!

Title: Street View

Genre: Horror/Found Footage

Logline: When a Google Street View driver unknowingly captures footage of a murder on a desolate highway, she must figure out what she has and who wants it before she becomes the next victim.

Why You Should Read: Why you should read it: Causeway Films in my native Australia (The Babadook, The Nightingale) recently broke their rule about not accepting unsolicited scripts after my pitch to them but provided only brief feedback about why they ultimately opted against adding it to their upcoming slate, so I believe I’m close enough that the Carson words of wisdom can hone it into something that I can get made. I feel it has the commercial appeal of the found footage/horror genre but also delves into deeper themes regarding the increasing privacy intrusions of big tech in our lives and the increasing divisions between people (particularly city and rural) that stem largely from Big Tech-facilitated ideological echo chambers. The Street View car driving through forgotten towns strikes me as the perfect embodiment of these themes. I’ve also had the awkward conversation of requesting the use of a rural property belonging to a friend of mine to film a home invasion scene where my friend had previously been a victim of a home invasion at that property! I think that chutzpah alone deserves a read. Also, this is the real camera used to take street view photos. The horror practically writes itself!

Title: POSSESSIONS

Genre: Supernatural Horror

Logline: An estranged daughter returns to her childhood home to help with her mother’s extreme hoarding only to discover her mother cursed by one of her many, many possessions.

Why You Should Read: Way back in December (Re: The Interventionist) you asked if anyone had done a hoarder horror movie. And then your review of 10/31 had a hoarder house in it and I was like, damn, I better finish my horror feature already! So after months of it sitting there waiting for it to be rewritten (again), I dug down and got to it. Gone is the Dead Kid Backstory in favor of a story more focused on a woman learning to take care of her aging mother… who happens to be possessed. Yay! I welcome any Marie Kondo / KonMari method jokes. Enjoy!

Title: Catharsis (note to writer: you need to retitle this, “Rage Room”)

Genre: Social Horror

Logline: Following a traumatic incident in a rage room, a spineless office worker develops strength and self-confidence — and an insatiable, murderous aggression that threatens to take over.

Why You Should Read: Rage rooms are simple: pay a small fee to occupy a room for 10-20 minutes and SMASH THE FUCKING SHIT out of mundane, breakable objects. With methods of choice ranging from baseball bats with home run dreams to sledgehammers that have never met something they couldn’t pulverize, you can customize your destruction of plates, printers, and other office or domestic fodder to your heart’s blood-pumping delight. All in the name of “self-care.”

In our current socio-economic and political climate, our globe is warming up to rage rooms in nearly 30 countries, with the US of A boasting 250+ locations that have increased exponentially in the last five years. The real kicker? The pursuit of catharsis often recycles its initial stimulants of stress and aggression. Meaning… this trend ain’t going anywhere soon. And just like escape rooms, you are trying to solve a puzzle: “What do I have to destroy to create a little peace and quiet?”

With this “Catharsis,” great power comes with great responsibility to gain more power, even if the objects in the way are made of flesh and bone. A good horror story should tackle relevant subject matter or universal fears or the dark symptoms of the human condition. Or, hey — crack open this PDF and try to find all three!

Title: INFANT

Genre: Horror

Logline: A sadistic rapist/murderer is captured by a quartet of women and infantized (shaved, crippled so he’s forced to crawl, diaper, etc) in order to re-educate him on how to treat women and act in society but the women instead use him for their own dark psychological needs until one decides they’ve gone too far and plots to free him.

Why You Should Read: INFANT is a proton torpedo into the Death Star of current society that was influenced by Frederick Friedel, Canucksploitation movies like CANNIBAL GIRLS and DEATH WEEKEND and LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT.