Search Results for: F word

Genre: Family/Fantasy

Premise: 13 year old aspiring inventor Andrew Henry begins to suspect that the world he lives in is not what it seems.

About: Didn’t research this until after I wrote the review, but it appears that Andrew Henry’s Meadow is a well-known children’s book, which would make this an adaptation, not a spec script, as I had originally thought. Although I don’t know as much about Adam as I do Zach Braff, I’ve read in several of Zach’s interviews that Adam is interested in writing children’s books, which would make this adaptation a logical choice. Zach Braff starred in the NBC sitcom, Scrubs, and went on to surprise Sundance back in 2004 with his well-crafted writing-directing debut, Garden State

. This is an early draft of the script.

Writers: Adam and Zach Braff (based on the 1965 children’s book by Doris Burn)

Details: 126 pages – 2004 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Well, for reasons I won’t get into here, today was supposed to be the review of my first “impressive” script (possibly even Top 25!) that I’d read in a long time. The script was “Seeking A Friend At The End Of The World,” which I’m guaranteeing will end up top 10 in this year’s Black List. But a series of events have prevented this from happening so instead I’m going to review Zach Braff and his brother’s script, Andrew Henry’s Meadow. However, if you’ve read “Seeking a Friend” and want to comment on it in the comments section, feel free to.

I didn’t know anything about Andrew Henry’s Meadow but the title made it sound like a more fantastical version of Garden State (Meadow? Garden?), so I was down. I’ll be the first to admit that Garden State’s script lacked some punch, but the movie was different and definitely captured the frustration and uncertainty that we often experience at different points in our lives. I was in that kind of mood so it sounded like a nice fit.

Well, as I would quickly realize, this wasn’t that script at all. Andrew Henry’s Meadow reads like a mix between Meet The Robinsons and The Goonies

. It also has a healthy dose of the 2004 thematic soup du jour, “Governments control us with fear.” (as seen in The Village

and Fahrenheit 9/11

).

13 year old Andrew Henry lives in a Truman Show like suburb where all the houses are the same and all the people are the same. In this fantastical version of our world, a single dominating company named Omnimega rules everything. OmniMega has built walls around our city to keep us safe from the “killer mutants” who would eat us up, regurgitate us, and eat us again if they only had the chance.

An aspiring inventor, Andrew finds a secret room in his house that contains an old book which states that, gasp, there are no mutants! That there’s nothing evil or scary outside of the city! So off he goes to test this theory, and finds that, indeed, all there are are big beautiful meadows as far as the eye can see. He begins to build the Michael Jackson mansion of all treehouses in this meadow, and soon other outcast kids, like himself, join him to help.

Naturally, he learns that Omnimega has made all this stuff up to scare people (hey, just like leaders in the real world do!) so he and his outcast friends must find a way to expose them before it’s too late (the Omnimega president is transmitting content through TV waves that keeps the populace in a zombie state). The plan is to break into the Omnimega TV tower, seize the production floor, and transmit the truth to everyone out there.

Okay, so, I’m sure you’ve already identified several things wrong with this script just by reading my summary. Most notably, it reads like an amalgam of two writers’ favorite movies. We have scenes straight out of the The Truman Show, The Village, The Goonies. Although I’m forgetting which one, the whole “TV static in people’s eyes” thing has been done in several super hero movies before. We have The Running Man ending with them trying to bust into the TV tower. That was easily the biggest fault in Andrew Henry’s Meadow. Every single development felt like something I had seen before.

But the problems with Meadow began before that. This is a laborious read. Open this up to any page and you will find skyscraper sized paragraph chunks that go on forever and ever. Over-description is an easy way to spot a new screenwriter, as they approach their scripts more like a novelist (since that’s where the bulk of their fiction reading has come from). You don’t need to tell us every little place your character walks, every little thing they see, every little way they react, every little crevice in their apartment. Only tell us what’s necessary for the story to continue. If you can’t describe an action beat in 3 lines or less, you’re probably writing too much description.

The direction of this story is all wonky as well. I understand that this is called “Andrew Henry’s Meadow,” but I’m not sure why we’re spending 20 some pages off in this meadow with all these kids building a tree house. To me, the story is that this Omnimega villain is trying to take over the city. When they’re out here in the meadow enjoying life and building things, there isn’t any story being advanced. It’s a completely separate storyline, which made most of the second act boring.

There’s a really good script that made the 2009 Black List called “Toy’s House,” where a high school kid builds a house in the forest and starts living there with his friends. That made sense because THAT WAS THE STORY – his building of that house and how it changed his life. In Andrew Henry’s Meadow, going to build this house feels like an unnecessary detour. Had they eliminated it, the story still would’ve made sense, which usually means it’s unnecessary.

Everything here takes too long to get to. It seems like we spend years before the inciting incident happens (he finds the book). It takes way too long for him to then get out of the city. I guess the “have fun in the meadow” stuff is supposed to be the second act, but since the second act is, by definition, the conflict stage of your story, it’s weird that this whole section is happy happy joy joy with no conflict whatsoever. This is followed by the “comes out of nowhere” Omnimega uses TV to hypnotize people subplot. Had that been set up earlier, it might have had a chance of working. Here it just…comes out of nowhere. And then the last act is so much like The Running Man that all we can think is, “Man, this is exactly like The Running Man.”

Now, it’s not all doom and gloom. Clearly, Zach Braff’s experience as an actor has taught him the importance of character, and while I didn’t fall in love with any of the characters in Meadow, I acknowledge that all of them were unique and interesting. We’ve seen the young shunned inventor protagonist before, but Andrew Henry’s underdog starry-eyed determined persona was easy to root for. Whereas in yesterday’s TV pilot, 17th Precinct, we only got the Cliff’s Notes version of each character, here, with Andrew, his parents, the girl he liked, his nerdy best friends, there was enough detail where the story could’ve centered around any one of them. And that’s not easy to do.

But the attention to character detail was the only thing that really worked for me. One of the most important things a script must accomplish is telling a story in a way that an audience hasn’t quite seen before. In other words, surprise us. If we can guess what’s coming around the corner every step of the way, if every plot development feels like, “Hmm, I’ve already seen this in another movie,” then the reader’s going to lose interest. And that’s how I felt reading Meadow.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In any script where you’re introducing a made-up world, there’s going to be more description than usual. However, there isn’t a more suicidal tactic in screenwriting than writing huge paragraphs. First of all, it depresses the reader. They know their reading time just went up by 50%. They hate sloshing through tons of extraneous detail to get to the important stuff. And sooner or later they just start skimming through those paragraphs anyway, causing them to miss key important details, which leads them to become confused later on. So only include the details in your description that are necessary to tell your story and NOTHING MORE. The reader will love you for it.

The thing that keeps every screenwriter up at night is the fear of boring the reader, the fear of writing a screenplay that isn’t any good. And here’s the terrifying reality. We’re all capable of writing horrible screenplays. From the guy who’s just starting out to the famous writer-director who pulls in 10 million a picture. Every single one of us, no matter how much we’ve studied the craft, no matter how many screenplays we’ve written…we’re all capable of writing a bad story.

But how can that be? You’d think that the more experienced you got at something, the better you’d get at it. Well, that’s true. The more time you put into screenwriting, the more likely it is that you’ll write something good. But it doesn’t guarantee you’ll write something good. In fact, I’ve received dozens of screenplays from writers who know way more about screenwriting than I do, and more than a third of them have been bad. So of course the first thing that pops into my head is, “Well if this guy, who’s an awesome writer, can write something shitty and not know it, where the hell does that leave my chances?” Is anyone safe? Is it that much of a crapshoot? Is there any way to minimize this horrible reality?

That’s why I’m writing today’s article. I’ve discovered some trends – or at least some red flags – that, if mitigated, can help avoid the deadly “bad script” pitfall. This is not the “end all be all” answer to this question. It’s more of a, “Be aware of these things whenever you write, as they often increase the likelihood that you’ll write something shitty.” We’ll start with one of the most common mistakes, “miscalculation.”

MISCALCULATION – Remember this: What is interesting to us may not be interesting to others. This is the number one reason a script from a good writer can fail. They’ve conceived of a story idea that they believe people will enjoy. But they were wrong. And really, everything that comes after that moment is doomed. Doesn’t matter how expertly they execute the idea. People just don’t care. Look at Spielberg with 1941 (I know he didn’t write it but he shepherded the writing of it). Look at Cameron Crowe with Elizabethtown

. Look at M. Night with…well, everything after The Village

. These stories were doomed from the outset because they weren’t interesting enough to be explored in the first place. The good news is, this one is correctable, and it goes back to what Blake Snyder preached

in his first book. You gotta go out and test your story idea on other people. See if they’re interested. Look for that excitement in their eyes when you pitch it. Be wary when you get the polite “That sounds good.” By simply testing your idea beforehand, you minimize spending the next year of your life on a bad screenplay.

PASSION PROJECT – (Incupatisa from the comments section defined a passion project perfectly, so I’ll repeat it here: “Broadly speaking, it’s a script one writes without a care in the world as to whether its sensibilities appeal to anyone but the writer.”) I’m not going to say that passion projects are bad. What I am going to say is that you’re playing with fire when you write them. You’re moving from the blackjack table to the dog races. As long as you realize you’re stacking the odds against yourself in a business where the odds are already stacked against you, then I’m okay with you writing a passion project. But here’s why I’d advise against it. Passion is good. It’s what keeps those page returns coming. But passion is also irrational. Passion blinds us from the truth. For that reason, whenever we’re working on our self-proclaimed “passion project,” we’re not seeing it the same way that the rest of the world is seeing it. We’re seeing this idealized perfectly constructed emotionally dazzling display of themes and symbolism and character flaws and introspection. They’re seeing a boring directionless story without a hook. The problem is (and I’m just as guilty of this as anybody), as writers get better, they’re more prone to believe they can overcome weak premises. This results in pretentious screenplays with no entertainment value. There are lottery winner examples of these scripts working (American Beauty) but more often than not, they’re never purchased or made, and even when they are, they’re both bad and lose a lot of money for people (Towelhead

, Away We Go

, The Pledge

). My suggestion with these scripts is to know what you’re getting into. Use them as character development practice or as a way to decompress in between sequences of that monster flick you’re working on. But please don’t depend on them. I know how satisfying they are to write, as they allow you to get into your own head and tackle some of those issues that have been bothering you. But 99% of the time, they’re boring to everyone else who reads them. If you ignore this advice and want to write one anyway, please please please add a hook (yesterday’s script, Maggie, is a good example – drop the zombie angle and that script never makes it past the first reader).

CHOICE – Regardless of whether you’re a structure nut or not, whether you follow Robert McKee’s teachings or avoid him like a fraternity bathroom, your script is going to require somewhere between 5000 and 10000 choices. From the characters to the subplots to the plot points to the scenes to the individual lines of dialogue, you’re constantly making choices when you write. And CHOICE is the one thing that comes from inside of you – that isn’t dictated by a screenwriting beat sheet. From what you find interesting, to the tone you’re trying to set, to the pace you’re trying to generate, to the level of complexity you’re trying to build. Every single choice you make affects your script. And this is where I think the good scripts get separated from the bad ones. A good script is a collection of good choices. And what I mean by “good choices” is choices that are unique, that are imaginative, that feel fresh, but most importantly, choices where you can tell the writer put some effort into them. I read so many scripts where on the very first page, the writer goes with the first choice that comes to mind. That to me signifies laziness. So I’m never surprised when the rest of the script is lazy as well. I mentioned a couple of months ago how Chinatown started with an investigation that turned out to be a lie. That’s an interesting choice. That’s what you should be aiming for. As a writer, you should be approaching your choices the same way you approach your concept. You wouldn’t write a so-so movie idea would you? So why write a so-so line of dialogue? A so-so character? A so-so story twist? I’ll tell you why you do. BECAUSE IT’S EASIER. The path of least resistance is always easiest. And sometimes we just want to take the easy way out. If you’d like to avoid writing a bad screenplay, put every choice you make to the test. Always ask yourself if you can come up with something better. Laziness, which extends from the bottom of the screenwriting totem pole to the top, is avoidable with effort.

ELEMENTS DON’T MESH – Now we’re getting into real trouble territory here. Of all the potential setbacks I’ve mentioned so far, this is the one you have the least amount of control over. Sometimes you have a good idea, and you write the screenplay, but for whatever reason, it just isn’t working. The problem is, when we work on anything for an extended period of time, we’re less likely to let it go. So we keep trying to force the elements together and make it work, unwilling to admit what we know in the back of our minds – that it’s never going to work. I’m not talking about problems in a script. Every script has problems. I’m talking about scripts where it’s clear the elements aren’t meshing the way you originally intended for them to. The 2006 movie, Reign Over Me, with Adam Sandler and Don Cheadle is a good example. It had good intentions, with a man grieving the loss of his family on 9/11 and reconnecting with an old friend. I still remember seeing the trailer and thinking, “That could be good.” But the video game stuff and the stilted reconnection scenes and the uncomfortable dramatization of the still raw 9/11 tragedy and the weird woman at the dentist subplot…. That combination of elements was never going to gel the way the writer imagined it would. So the lesson here is that you gotta be able to move on. Being honest with yourself is painful, but it’ll be less painful than the drubbing you’ll get when someone reads your script and thinks you’re a boring writer.

X-FACTOR – This one isn’t so much about what makes your script bad, as what makes your script average. If you don’t find that X-factor, no matter how hard you work on something, it’s never going to rise above “liked it didn’t love it” status. The X-factor is basically that indefinable “thing” that elevates a script into something special. In the above section, I talk about what happens when the elements don’t come together. The X-factor is the opposite. It’s what happens when the elements not only come together, but come together perfectly. Take a look at a movie like Zombieland. You have voice over, a set of rules for escaping zombies, four very distinct characters, flashbacks, a road trip, a unique and fresh sense of humor. All those elements lined up perfectly to make that script pop off the page. Star Wars

is probably the best example of this, as it contains a good 30 central unique elements and they all come together perfectly. Had that not happened, we could’ve easily gotten Dune

a decade early. The surest path to locking down that elusive X-Factor is to come up with a concept/hook that gets you excited (never write anything that doesn’t get you excited), give it a story you’re passionate about, and populate it with characters you love. In other words, you need to love the story you’re writing. If you don’t love it, people will always comment that there’s something missing, and that something is usually the “x-factor.”

Hey, it sucks that despite all these scripts we’re reading and how much we’re learning about this craft, we’re still capable of writing shit. But at least this way, you have an idea of what causes that shit. I’m sure I missed some things though, so if anyone has any theories on why the man who wrote arguably the best screenplay ever (Chinatown) can also write Ask The Dust, as well as similarly talented screenwriters stinking it up, drop some knowledge in the comment section below.

Genre: Drama

Premise: A woman forces her husband into couples therapy to save their marriage.

About: This script originally made the 2008 Black List under the title, “Untitled Vanessa Taylor Project.” It more recently gained the “Great Hope Springs” title when it secured heavyweights Steve Carell and Meryl Streep in the cast. Actors rumored to be playing the husband are James Gandolfini and Tommy Lee Jones, both of whom I think are spot-on choices who would do a great job – Jones in particular would be awesome. The movie was originally a directing vehicle for Mike Nichols, but is now being headed up by David Frankel, who’s become hot after having two surprise hits in a row: “The Devil Wears Prada” and “Marley and Me.”

Writer: Vanessa Taylor

Details: 108 pages – June 20, 2008 Black List draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Okay, we have two slow-moving stories this week and I didn’t like one of them. So I want to preface this by explaining why I liked Great Hope Springs a lot more than that Wednesday review. Remember, the biggest influence on a reader liking a screenplay is subject matter. If they’re interested in the subject matter, they’re miles more likely to be interested in that film/script. And this subject matter is right up my alley.

I’m fascinated by marriage. I think we’re at a point in society (at least here in the U.S.) where the institution of marriage is on its way out. Not only are more people getting divorced. But the divorce rate is causing more people to fear marriage, to not get involved in the first place. And I think that’s the result of a lot of things. But the biggest thing is that people don’t persevere anymore. When something goes bad, they don’t try and fix it. They just walk away. And without trying to sound too corny, I believe that the people who stand up and fight for their marriage are some of the last heroes out there, because it’s so much easier to pack it up and move on. And that’s exactly what today’s script is about. It’s about a woman trying to save her marriage.

52 year old Maeve Soames (“sweet and sexless”) doesn’t exactly have a wonderful marriage. She’s got two grown kids, but they’ve both moved out, and that leaves just her and Arnold, her hard-nosed husband, the kind of man who ends every day telling you how pissed he is about some client at work. Not exactly a bright bowl of cherries. If you have any questions about where this marriage currently stands, the fact that the two sleep in different bedrooms might give you a clue.

That’s not to say they don’t like each other. They just don’t see each other as emotional sexual human beings anymore. Their relationship has turned into a second business, one you try to manage and maintain but are ultimately emotionally absent from. And Maeve is sick of it. So sick, in fact, that she lays down an ultimatum. Either they go to an intensive marriage therapy doctor in Wyoming or she’s leaving. Arnold thinks this is a classic “wife bluff,” something you endure, wait for them to calm down, then move on from. But he quickly realizes she’s very serious, and therefore has no choice but to join her on the trip.

Cut to a tiny town in the middle of nowhere that’s looking a lot more like a prison to Arnold than the picturesque headquarters of a famous marriage counselor. Dr. Bernie Feld plays the unique role of both hero and villain in the story – hero to Maeve and villain to Arnold. Arnold’s hatred for this man and his practice stems mostly from the ridiculous $4000 price tag he’s set on this week. As he says to Maeve, “That could’ve been a new roof.”

Almost immediately, we jump into therapy, and this is where the meat of Great Hope Springs is. In every movie idea you come up with, you’re looking for areas that are going to provide the most amount of conflict, where the main source of resistance is going to come from. Here, it’s these sessions, specifically the fact that Maeve desperately wants to be here and Arnold desperately doesn’t.

Not only is Arnold unable to open up, but he believes therapy to be a crock of shit, so the sessions are packed with tension both from the marriage stuff AND from him not wanting to be here. So intense are these early sessions, you get the feeling that at any moment, the room could explode. At the core of the problem is that Arnold believes the marriage is fine. That sleeping in different rooms, not talking about anything meaningful, never doing anything fun or romantic, is perfectly okay. As long as you put in the time (the marriage is over 30 years old), then you’re entitled to coast.

So he’s shocked and angered that Maeve doesn’t feel the same way, not realizing that this is the main issue – that they don’t talk enough for the other to even know that there’s something wrong. But with Maeve now making it clear that if he doesn’t change, she’s out the door, Arnold realizes that he better at least try and give Dr. Feld a chance, or the one mainstay in his life could be gone forever.

One of the cool things I noticed about Great Hope Springs is that while it has that “indie” character piece feel, the structure is textbook. We have a clear goal – save the marriage. We have a ticking time bomb – one week. And the stakes are sky high – a 30 year old marriage is on the line.

But like I said, what really makes Great Hope Springs fly is the conflict, or more appropriately, Arnold’s resistance to change. Remember that. If you don’t have at least one character in your screenplay who’s resistant to change, there’s a good chance you’re not getting the most emotional punch out of your story.

And the less likely it appears that that character will be willing to change? The more compelling it will be. That’s the case with Arnold here. He hates admitting he’s wrong, he hates therapy, he hates this therapist, he hates that Maeve’s making him do this, he hates this town. We’re thinking, “There’s no way in hell this guy is going to change his mind.”

Another thing I like about the structure is that Taylor uses the therapy sessions as pillars to keep the story moving. Each session is packed with conflict, so they’re always interesting. But then you also have Feld giving them a goal to try before the next session (i.e. go have sex). That way, once we leave the session, we’re interested in whether they can achieve this goal, and we’re also looking forward to what challenge will be presented in the next session.

Another thing to note about Great Hope Springs is the unique way that therapy allows you to do things with your characters that you wouldn’t normally be able to do. Most scripts, especially emotional character-driven scripts like this, thrive on subtext, the unspoken words that live between the words that the characters are actually saying. But when you put a character in therapy, there’s no more subtext. Essentially, you’re allowing the characters to do what you, as a screenwriter, are told never to let them do, which is to speak “on the nose,” – say exactly what’s on their mind. But the reason that it works is because it’s motivated. They HAVE to say how they feel. They have no other choice. So if you’re looking for that opportunity to have your characters get right to the point, throwing them into a therapy session might be a good idea.

I do have a few problems with Great Hope Springs though. First, the last 35 pages don’t live up to the rest of the script. What I liked about this story was that the therapy kept building, kept providing new challenges every time they came in. But towards the end, once we get to the sex-related stuff, the therapy kind of becomes redundant. We’re battling the same problem over and over again and after awhile it just became stale. This is followed by a lackluster unimaginative ending. In fact, it felt so tacked on that I wondered if it wasn’t a placeholder ending.

Finally, I wish there was more humor here. And with Steve Carell coming on, I’m guessing that’s a direction they took in subsequent drafts. Which is a good idea. Because while the conflict in this script is excellent, there aren’t enough laughs to release all that tension. If they fix these few issues, this could be a superb character study, and one of the better movies about marriage ever made.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Somebody has to change in your story. It may not be the hero. It may not even be the love interest. But change – or the attempt to change – is the key emotional component that drives an audience’s interest, so at least one character should experience it. And the more resistant they are to that change, the more compelling their journey tends to be.

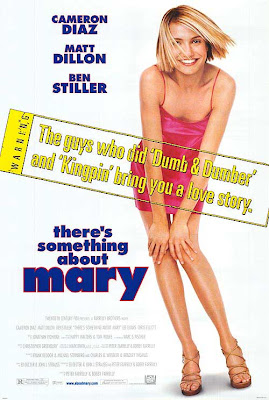

It’s Comedy Theme Week everyone. For a detailed rundown of what that means, head back to Monday’s post, where you’ll get a glimpse of our first review, Dumb and Dumber. Tuesday, I took on the best sports comedy ever (yeah, I said it), Happy Gilmore. Wednesday was Grouuuuuundhog Day. Thursday, Wedding Crashers. And for our final film of the week, one of my favorite comedies ever, There’s Something About Mary!

Genre: Comedy

Premise: 15 years after a horrifying prom night accident, a man decides to take a second shot at the girl he fell in love with. Only problem is every other man in the world wants her too.

About: The movie that propelled cinema into a decade of gross-out humor (some of which is still going on today), There’s Something About Mary became a sleeper hit back in 1998, bringing in 176 million dollars at the box office. In one of the best known gags in the film, where Mary erroneously mistakes Ted’s semen for hair gel, Cameron Diaz was said to have fought the gag ferociously. Her argument (which was rather sound if you think about it) was that a woman on a date would be checking herself constantly, and therefore would never have her hair like that. The Farrelly’s finally convinced her to give it a shot, and we subsequently got one of the most memorable moments in film history.

Writers: Peter and Bobby Farrelly

There’s Something About Mary is in my top 3 comedies of all time. The structure, much like the Farrelly’s other movie I reviewed this week, Dumb and Dumber, is all over the place. But the reason this film makes you laugh is because it has some of the best comedy set pieces ever written. And it’s a testament to how finicky comedy is, because I’ve seen the Farrelly’s create countless set pieces since then that just weren’t funny. And that’s one of the reasons I wanted to revisit this classic. I wanted to figure out what made this one different.

First, the structure. Again. Three words. “What the hell?” This is a really oddly-structured film. The movie places its first act in the past, establishing Ted and Mary’s relationship as teenagers. It then spends its entire second act with the two apart. I want you to think about that for a second. A romantic comedy (which is what this essentially is) keeps its two leads apart for the entire middle portion of the movie. What the hell?

It gets weirder. We started off with Ted as our main character. But the middle act actually switches over and makes Mary the main character, occasionally giving the spotlight to Healy (Matt Dillon’s private detective villain). So the entire middle act is dedicated to a relationship which isn’t the main relationship in the movie. The main relationship, Ted and Mary, doesn’t get kickstarted again until the final act! That’s when Ted arrives in Florida and makes his move on Mary. The third act then becomes its own little romantic comedy, with the traditional, “Guy gets girl, guy loses girl, guy gets girl back.” With montages and everything!

So why does it still work? Well, I think I know. All of the guy characters in this movie have incredibly strong goals: “To get Mary.” That drive means that it doesn’t matter whose story we jump to, because when we get there, that storyline will have intense forward momentum driven by that character’s pursuit of that goal (Mary). Also, through it all, the story’s driven by our ultimate wish, to see Ted get Mary. In fact, outside of When Harry Met Sally, I don’t know of a comedy or romantic comedy where you want the two main characters to get together as much as this one.

And I think that’s a huge part of why the movie works. There’s Something About Mary spends the first 90 minutes of its running time building up Ted’s attempt to get Mary. Remember how yesterday I said the reason Wedding Crashers was weak was because the stakes were low? Well here, the stakes are as high as they can possibly be. The reason we care so much in the last 30 minutes is because we’ve just spent the entire movie watching Ted go through hell and back to get to Mary. This build-up is what makes their scenes together so captivating. Because they’re packed with the tension of “Will this work out? Does he finally have her?” Go back and watch that scene where Ted first meets Mary again. In that 3 second moment after Mary responds, “Didn’t we just do that?” to Ted’s asking her if she wants to get some coffee and catch up, I can’t remember a time in movies when my heart sank that much. And it’s all due to the buildup of stakes.

Attention to stakes is also the key to one of the most famous comedy scenes ever, when Ted gets his balls stuck in a zipper. The reason this scene works so well is not because, “Wowza! His nuts are stuck in a zipper!” It works because for the last 20 minutes, the writers have built up that this is the single most important moment in Ted’s life. Somehow the nerdiest kid in school has pulled off the impossible – he’s taking the prettiest girl in school to the prom (stakes)! We are on pins and needles begging that this works out. So when it starts to backfire, and when that fateful zipper moment comes, and we’re hoping and praying he somehow fixes it in time to still go to prom. When it doesn’t? And the situation continues to get worse instead? It breaks our heart. Because we know this is it. You don’t get a second chance to take the prettiest girl in school to prom.

The scene also does double duty, creating a key residual effect. That terrible situation he went through? That losing of the chance to go out with the most popular girl in school? It makes Ted the single most sympathetic character in the world. I mean we’ll go anywhere with this guy after that. And so when we learn that he’s going to take another shot at Mary, even if he’s going about it creepily and hiring a private investigator? We don’t care. Because we believe he deserves that shot. And whereas yesterday the goal of getting some random girl at a wedding made Wedding Crashers’ driving force weak, the pursuit of the perfect girl who you lost out on when you were in high school because of a freak accident…that goal is about as strong as they come.

I want you to think about that because it’s an important screenwriting lesson to remember. What happens if Owen Wilson loses that girl? Let’s see. He loses out on a girl he’s known for all of 24 hours. No offense but: BIG FUCKING DEAL. He’ll get over it. But with Ted, this is the girl he’s spent every day for the last 15 years thinking about. It’s personal. There’s history there. If he loses this girl, you feel there’s a good chance it will destroy him for the rest of his life.

The Farrelly’s, like Happy Gilmore, have also created a great villain. Unlike the one-dimensional forgettable villain in Wedding Crashers, Tad Healy has a ton going on. He’s smart. He’s funny. He’s slimy. He’s good at what he does. This is what I mean when I say, “Add some dimension to your villain.” Again, you could’ve just made him a great big asshole. But Healy is much more than that, which is why his character is so memorable.

Another thing I like about the Farrelly’s comedy is they always ask the question, “How can we make this worse for the character?” And when you do that, you usually end up with something funnier. So in the scene where Healy drugs the dog so it likes him and impresses Mary, they say, “How can I make this worse for Healy?” Well, what if the dog died? So now the dog’s dead. And now Healy has to do the whole “CPR” bit on the dog and bring it back to life before the women come back in the room. You see this device being used again and again throughout the movie, especially on Ted, and it’s a big reason for all the hilarious set pieces.

But I think the thing that sticks out to me most when breaking down this film, is how wonky that structure is. The Farrellys have really weird structures to their films. Just like Dumb and Dumber, we have our heroes starting in one place, driving to another, and then beginning a relationship in the final act. But Mary is even more complicated, since the second character (Healy) is our villain, and isn’t with Ted on his trip. Therefore you have this cross-cutting storyline going on in the second act where we’re jumping back and forth between Ted’s journey and Healy and Mary’s courting. I have to admit, it’s different from any comedy plot I’ve read, and I get the impression that Peter and Bobby haven’t ever looked at a manual on how to structure a screenplay. This is why Dumb and Dumber and Mary feel so fresh. They don’t go how you think they’re going to go. However, before you jump on that bandwagon, it’s important to note that this seems to hurt them just as much as it’s helped them. They have some dreadfully unfunny movies in their vault, many of which peter out near the end (Stuck On You, Me Myself and Irene, and The Heartbreak Kid), and a lot of that is structure-related.

Lots of other things to take away from this movie. I didn’t get the chance to show, once again, how much effort the Farrellys put into making you love their hero (he befriends the retarded brother. He wants to help out Mary even after learning she’s 250 pounds and in a wheelchair), but I think it’s safe to say that a big part of the formula for their success is making sure you love and root for their protagonist. I also thought this was one of the few “romantic comedies” to create a fully rounded female character. She was maybe a wee bit on the wish-fulfillment side (she loves sports, likes to hang with the guys, doesn’t care about looks) but Mary is definitely different from every other romantic comedy lead female you’ve seen. There’s Something About Mary is one of those few screenplays that takes chances, breaks the rules, and those changes actually end up making the final product better. I can’t tell you if this happened on purpose or by accident. All I can tell you is that it worked.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[x] genius

What I learned: KYFC! Know your fucking characters! I’ve been encountering this a lot lately in the amateur screenplays I’ve been reading. Writers aren’t thinking about their characters! They don’t know what their character does for a living, what their passion is, what their dreams are, what their vices are, what their bad habits are, what they like in the opposite sex, what their education is, what state they grew up in. I used to be of the opinion that this stuff didn’t matter. I’ve done a 180 on that and let me tell you why. I’ve realized that a lot of boring dialogue comes from the fact that the writer doesn’t know enough about the character who’s speaking that dialogue. When you don’t know that person, you give them generic lines. Let me give you an example. There’s a moment where Mary’s roommate, the old woman, asks her if Matt Dillon, who she’s going on a date with, is cute. She replies, “He’s no Steve Young.” Now this is by no means an earth-shattering line of dialogue. However, it’s a line of dialogue that could only come from Mary herself. It’s a line of dialogue that tells us a lot about who Mary is (she likes football – which is also established earlier in the screenplay when she’s telling Ted about her love for the 49ers). Without knowing that Mary is a woman who loves football and the 49ers, we may have heard a more generic response such as: “He’s all right I guess.” That’s a line that anybody in the world could’ve said. It’s generic and uninteresting. And the less you know about your characters, the more lines LIKE THAT are going to come out of your characters’ mouths. Add enough of them up, combined with enough lines from other characters who you don’t know well, and the more non-specific lacking-of-insight boring generic dialogue you’re going to get. So people, please: KYFC!

What I learned from Comedy Week: In 4 out of 5 of this week’s comedies, the writers went out of their way to make their characters sympathetic. Loving the characters may not be a requirement (you don’t love Phil in Groundhog Day), but in comedies, it helps a lot. Also, in 4 out of 5 of the comedies, the characters had incredibly strong goals. I can’t stress this enough. The more your hero wants to achieve his goal, and the bigger and more important that goal is, the better your script is going to be. It’s no coincidence that the script with the weakest central goal (Wedding Crashers) was also the weakest of the comedies. Outside of that, the rules are fairly wide open. Just try to keep the stakes up, not just for the film but for the set pieces and individual scenes as well. Add multiple dimensions to your villain to make him memorable. And make sure your concept is funny to begin with! Any other trends you guys caught from this week’s entries, please include in the comments section! :)

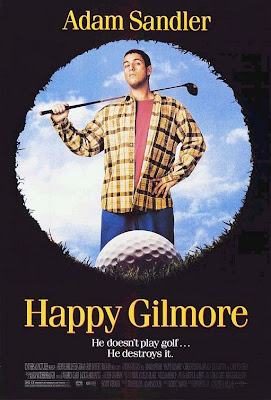

It’s Comedy Theme Week everyone. For a detailed rundown of what that means, head back to Monday’s post, where you’ll get a glimpse of our first review, Dumb and Dumber. Today, I’m taking on the best sports comedy ever made, Happy Gilmore.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A failed hockey player is forced to join the pro golf tour in order to save his grandmother’s home.

About: As not many people saw Adam Sandler as a movie star at the time, Happy Gilmore did only so-so at the box office, taking in 38 million dollars. The movie, however, would later become a huge hit on video and help propel Sandler into becoming one of the highest paid actors in the world. Roger Ebert said of Sandler’s performance at the time, which he did not like, that he “doesn’t have a pleasing personality: He seems angry even when he’s not supposed to be, and his habit of pounding everyone he dislikes is tiring in a PG-13 movie.” As I find Sander’s anger to not only be the funniest part of the film, but an integral part of his character and character arc (and thus organic to the story), it just goes to show how polarizing reactions to comedy can be!

Writers: Tim Herlihy and Adam Sandler

Leave it to Adam Sandler to restore some normalcy to the craft of screenwriting.

Uhhhhh….what?? Did I just mention Adam Sandler and screenwriting in the same sentence? And that sentence didn’t include the words “dreadful,” “incomprehensible,” “horrifying,” “unreadable,” or “brain-cancer-inducing?” I believe I did. Yes, believe it or not, before Sandler and his “writing team” began invading our cineplexes with movies like “Has-Beens Hanging Out At A Cabin” or whatever the hell that piece of crap was with him and Chris Rock and Kevin James, he actually made a few good movies. And Happy Gilmore, by a country mile, was the best of them.

While yesterday’s comedy made all sorts of funky structure-breaking choices that confused and confounded me, Happy Gilmore is one of the most straightforward by-the-book executions of the three-act structure there is. In fact, if I was going to recommend a template for the execution of the single protagonist comedy, I would put Liar Liar first and Happy Gilmore second. As shocking as it sounds, this screenplay is a thing of beauty.

As many of you know, Happy Gilmore is about a lousy hockey player with anger management issues who’s forced to become a professional golfer in order to save his grandmother’s house. Happy’s unique talent is his ability to drive the ball further than any professional golfer in the world. But after his success begins to draw the ire of tour hot shot and universal asshole Shooter McGavin, Happy finds himself not only struggling to win back his grandmother’s home, but trying to defeat the best golfer in the world.

What I love about Happy Gilmore is that it follows all the rules, yet still manages to feel fresh and funny. It starts by giving us a hero with a flaw. Happy has anger issues. This flaw, while admittedly simplistic, gives our character some depth, something to overcome during the course of his journey. And even better, in “proper” screenwriting fashion, we find out about this flaw not because our hero or some other character *tells* us he has anger issues. We find out through his *actions*. After not making the hockey team, Happy proceeds to beat the shit out of his coach.

This is followed by the inciting incident, the moment in the screenplay that incites a call to action. Happy’s grandmother loses her house because she didn’t pay her taxes. She owes $250,000 dollars and if she doesn’t come up with it within 90 days, the house will be sold off. So our character goal is set: Get $275,000 before the 90 days is up.

In order to beef up that goal, the writers make sure you know that the grandma is the nicest sweetest coolest most loving woman in the world. And because you love her, you want to see Happy get her house back for her. Also, remember how the other day I was talking about positive and negative stakes? How you want your character to not only GAIN something if he wins, but LOSE something if he loses? We have that here when we find out Grandma is staying at the nursing home equivalent of a concentration camp. If Happy gets the money, he gets her house back. If he loses, she’s stuck in this hellhole forever!

But here’s where the genius really kicks in. For most movies to work, your hero must DESPERATELY WANT TO ACHIEVE HIS GOAL. If your hero doesn’t want to achieve his goal, then what’s the point in watching? He doesn’t really care. So why should we? But if someone’s desperately going after a goal doing something they enjoy, where’s the fun in that? Especially in a comedy. It’s much more fun if they DON’T like what they’re doing. And Happy hates playing golf. So then how do you make someone despereately want to achieve something if they don’t like what they’re doing? Simple. You force them into it. So Happy hates golf, but he HAS to play it. And this conflict he has with the sport is what leads to the majority of the comedy in the movie. Again, CONFLICT BREEDS COMEDY. This is how we get Happy swearing up a storm as he tears up a pack of clubs on national TV while the Tour President tries to calm down the sponsors. Or how we get the classic comedy moment of Happy fighting Bob Barker. It’s the key component to the movie working, that Happy wants desperately to achieve his goal, but still hates what he’s doing.

One commonality we see between Happy Gilmore and Dumb and Dumber is that the writers work really hard to make sure you love the main character. We start out with Happy’s voice over. Voice overs always get you into the head of your hero, breaking that fourth wall and making you feel like you know them. So it’s a great device to create sympathy (though still dangerous!). Through it, we find out that Happy lost his father when he was young (sympathy). Happy doesn’t make the hockey team (more sympathy). Happy gets dumped by his girlfriend (more sympathy). Happy employs a homeless man as his caddy (more sympathy). But what you may not have picked up on, is that there’s a very subtle twist to all of these sympathetic moments to draw our attention away from the fact that the writers are pining for our sympathy. Each moment is cloaked inside comedy. In other words, because we’re laughing, we forget that the writers are blatantly manipulating us. When Happy gets kicked off the team, he hilariously beats the shit out of the coach. When his girlfriend leaves him, he screams at her through the intercom (she eventually leaves and Happy is talking to a young boy and an aging Chinese maid). It’s very cleverly disguised inside comedy, and a neat trick to use in your own comedies.

Another great touch is that Happy Gilmore constructs the perfect villain: Shooter McGavin. A lot of writers think you just throw an asshole into the mix and that’ll be enough. Crafting a villain, even in a simple comedy, requires a lot of work. You have to give us someone we hate, but not in that obvious cliché stereotyped way. The mix here of arrogance, passive-aggressiveness, fakeness, and elitism, along with all those annoying little traits (his little “shooting of the guns” and recycled jokes) makes Shooter just a little bit different from the other villains you’ve seen in comedies.

Even the love interest is perfectly executed here. Usually, the love interest in a non-romantic comedy is unnaturally wedged into the story to appease producers. Here, it feels organic to the story. The romantic lead (who’s Claire from Modern Family btw) is the public relations director of the tour. So when one of the tour players is acting up (in this case, Happy Gilmore), it’s only natural that she be brought in to keep him in check. This stuff sounds like it just happens. But you gotta be on your game to make it feel natural. And you have to admit, you never question it in Happy Gilmore.

Chubbs (the one-armed golf pro) is also organically integrated into the script. Whenever you write a sports comedy, you want to not only have an internal flaw (anger, in this case) that the hero battles, but an external one as well, so there’s something physical they have to fix in order to achieve their goal. Here, it’s Happy’s putting. That’s what’s preventing him from beating Shooter. This is the reason Chubbs becomes essential. He has to teach Happy how to putt. Again, it seems obvious, but that’s because it’s so well done.

Another key that makes Happy Gilmore work – and a requirement for any good comedy – is that it exploits its premise. Whenever you come up with a comedy idea, you want to make sure you have 3 or 4 scenes that showcase that idea. That’s why the Bob Barker fight is genius. That’s why Chubbs taking Happy to the miniature golf course and Happy getting in a fight with the laughing clown is genius. These are the moments that represent the audience’s expectations of the idea. If you’re not including these scenes, you might as well not write the movie.

Happy Gilmore is also an incredibly tight script. That was another reason Dumb and Dumber threw me for a loop. It’s over 2 hours long. Most comedies need to be short. You’re making people laugh. Not giving them a history lesson. So by making Happy Gilmore a lean 93 minutes long, it forces the writer to make every scene count. And indeed, every single scene here pushes the story forward. Even the most questionable story-related scene, the pro-am tournament with Bob Barker, sets up Shooter’s goon/cronie who later tries to take down Happy in the Tour Championships.

This is by far the best sports comedy ever made. And just as a straight comedy, it’s pretty high up there as well. If you’re writing a comedy with a single protagonist trying to obtain a goal (like most comedies), you definitely want to study the structure of Happy Gilmore. It’s pretty much perfect.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Look to make your villain unique through a combination of traits. Shooter McGavin is clever (sending Happy to the 9th tee at nine), passive aggressive (offering backhanded compliments whenever asked about Happy’s talent), cowardly (backing away from a fight) phony (pretending to care about his fans when all he cares about is himself). This combination of qualities gives him a depth that you don’t often see in comedic villains. Making your villain a straight-forward asshole may get the job done, but layering him with numerous quirks and traits will separate him from all the cliché villains of the past.