Search Results for: the wall

This juicy high-concept show starring Mahershala Ali will be Hulu’s next big buzzy “whodunnit.”

Genre: Thriller/Mystery

Premise: A once successful author does the unthinkable and steals a former student’s book idea after he learns of the student’s death. But after the book becomes a #1 bestseller, someone on social media begins taunting him, telling him he knows what he did.

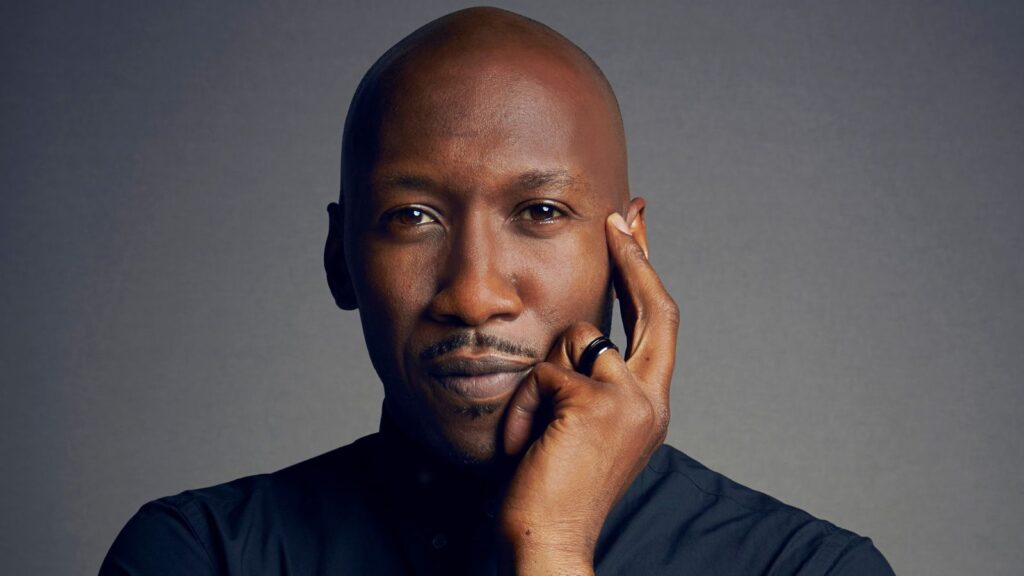

About: Today’s author, Jean Hanff Korelitz, originally wanted to be a literary novelist, writing “important” and “thoughtful” character-driven stories. Until she realized the reality of her voice as a writer: SHE LOVED PLOT. Thus was born, “The Plot,” a book she said was the perfect writing experience. It shot out of her, uninterrupted, in six months during the pandemic. The sexy concept was quickly picked up by Hulu to turn into a series, which will star Academy Award winner, Mahershala Ali.

Writer: Jean Hanff Korelitz

Details:350 pages

Since we’re talking about the power of concept today – coming up with that big juicy movie idea – I wanted to remind you guys that I do a “Power Pack” logline consultation for 75 bucks. You send me 5 loglines. I give you analysis, rate them on a 1-10 scale (don’t write a script that gets less than a 7!) I rewrite each logline, and I rank them from best to worst. This is great for writers trying to figure out what script to write next.

I also do a la cart logline analysis. It’s $25. Use my expertise of having been pitched over 20,000 loglines to know if your idea is truly worth writing. Just e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com

Okay, on to today’s review. We’re going to talk about a lesser-known sub-genre in the storytelling universe called the “walls are closing in” narrative. Now, the “walls are closing in” narrative has a couple of advantages and one distinct disadvantage.

What it offers is this impending feeling of doom as the truth begins to close in on our hero. You’ll see this in movies where the main character has killed someone and the cops come sniffing around. As the story goes on, we can almost physically feel all avenues of escape shrinking. The walls come from around, above, and below, squeeeeeeezing until they’ve entrapped our protagonist.

It’s a fun narrative because we’re hoping that the protagonist somehow figures out a way to escape.

But there’s a second advantage to these movies that not a lot of writers are aware of. Which is that the main characters are a lot more interesting than your average main character. They’ve obviously done something bad in order to be placed in such a situation. That life-changing mistake creates this internal battle that the character must fight off throughout the story. You know you’ve written good characters when the story stops and we still want to watch those characters. The main reason we’ll want to do this is because they’re going through some major internal struggle, which is exactly what the “walls are closing in” narrative provides.

But that leads us to the downside of these narratives, which is that the characters leading them are passive. Often times, with “walls are closing in” narratives, the main character is waiting around. They’re hoping they don’t get caught. At best, the characters are running around, defensively protecting themselves from being discovered.

As you may know, the best stories are almost always stories where the main character is active. He’s going after something. Let’s see how The Plot addresses this.

Jacob Finch Bonner was once a prodigy. His book, “The Invention of Wonder” was critically acclaimed and became a New York Times best-seller. But it’s been a decade and, two books later, Bonner is seen as an also-ran, one of many famed authors who fell off a cliff.

It’s gotten so bad that Jacob was forced to accept a teaching position at a writer’s summit in a small college called Ripley. Dozens of writers paid to come and learn writing from real authors for a month and then went off and tried to apply their newfound knowledge to their own novels.

While there, Jacob meets the most pompous writer ever, a handsome kid named Evan Parker, who has the gall to tell Jacob that he doesn’t need any writing help. He already knows he’s a great writer. He just needs contacts for when he finishes his book, a book, he claims, that will be one of the best books ever.

Jacob internally laughs this off but then, in a private meeting after class, he asks Evan to tell him about the book and Evan does. Jacob is shocked to learn, as Evan goes through the plot, that it, indeed, will be one of the best books ever written. There’s no hesitation in that analysis. The story, which includes a whopper of a twist, is *that* good.

The summit ends, everyone goes their separate ways, and three years later, out of curiosity, Jacob looks up Evan Parker. He’s confused why he hasn’t seen Evan’s book get published. As it turns out, Evan is dead. He died of an overdose.

It doesn’t take Jacob long to decide what he’s going to do. He’s going to write Evan’s book. And he does. Cut to three years later and Jacob is back on top of the publishing world. But “Crib’s” success dwarfs anything he experienced with The Invention of Wonder. Even Oprah wants to interview him.

Evan even gets a wife out of it! A producer on a Seattle radio show named Anna first falls in love with the book, then with the man who wrote it. And Evan is living every writer’s dream. Until one day, on his website, someone leaves a comment: “You are a thief.” From that point on, Jacob’s dream becomes a nightmare.

Not because anyone is trying to kill him. Because now every minute of Jacob’s life is a minute lived in fear. Will today be the day he’s exposed? At first, the comments come every couple of months. But the mystery person gets on Twitter and starts telling anyone who will listen, that Jacob stole “Crib.”

It gets to the point where the publisher finds out and now they want to know what’s up. Jacob, of course, tells them it’s a lie. But it’s getting bad enough that he can’t just wait around anymore. So Jacob heads back to Ripley College, the area where Evan Parker lived, to see if he can learn anything about who Evan was close with, in the hopes of finding the troll. What he learns is that he already knows the answers to his questions. Because the answers are written in his book.

“The Plot” is a great example of how to come up with a low-key high-concept idea. When you think of high concept, you usually think of something involving dinosaurs, time travel, switching faces. But there’s this whole other range of options below the high-profile versions of high concept that can give you a more affordable great idea.

Some low-key high concept movies that come to mind are Double Jeopardy, Her, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Groundhog Day, Memento, Limitless, and Yesterday.

A writer who steals a concept from a dead writer only to learn, after his outsized success, that someone knows his secret, is indeed, a juicy setup for a movie (or, these days, a show) that isn’t going to break the bank. Which is why everyone on this site should familiarize themselves with low-key high-concept. Still, to this day, it’s one of the best ways to skip the Hollywood line.

And like I said at the outset, the idea lends itself to a fun “walls closing in” narrative, which I think the writer executes well. That first message Jacob gets (“You are a thief”) reminded me of that famous 90s horror thriller line: “I know what you did last summer.” I was scared for Jacob. Because it’s a unique threat in that there’s nothing you can do about it. At least not yet. All you can do is wait and hope that it somehow goes away, even though you know it won’t.

But what impressed me about The Plot is the thing that I keep telling every writer to do. Find a familiar concept/format/genre/plot and put a spin on it. The Plot is a “whodunnit”….. EXCEPT THERE’S NO MURDER. That’s what makes it unique. Once Jacob decides to do something about this troll, he becomes an investigator. He travels to Evan’s old town to learn about him and, hopefully, figure out who’s sending him these messages.

By the way, that’s how the book handles the “walls are closing in” weakness. It gives its main character a goal of finding out who’s posting these comments. That makes him active. So he’s not standing around the whole show.

Ironically, it isn’t the plot that puts this book on top. It’s the thing that the author claims to be least interested in: character. Because what this story is really about is the struggle of being a fraud. It’s a lot like “Yesterday” in that sense. You have everything you’ve ever wanted. But do you really have it if you ripped off the idea from someone else?

And that’s where The Plot becomes its most interesting, at least for fellow writers. Because it gets into a nuanced discussion about what constitutes “stealing.” Jacob wrote every word of this book. He didn’t use a single line of Evan’s work. So did he really steal? Evan had this plot. And he had this amazing twist. But Jacob wrote it. And that’s what he’s holding onto to keep his sanity. He keeps reminding himself that he wrote everything. But is he just doing that to feel better about what he’s done?

The big weakness in the book is the excerpts from the novel, “Crib,” that Jacob wrote. It’s supposed to be this amazing novel (it basically follows a toxic mother-daughter relationship) but nothing in Crib is as good as anything in the novel we’re reading, “The Plot.”

With that said, “Crib” starts to get juicier towards the end when we realize that the characters in “Crib” were Evan’s mother and sister. Now, if someone tells the world what happened to Evan’s mother and sister, it will clearly expose Jacob as having stolen the story from someone else.

I’m back and forth on whether this should be a series or a movie. Ideally, it would be something between the two. That’s always been the problem with novel adaptations. They’re always too big to be a movie and too small to be a TV show. So if you’re going to make a TV show, you need really good writers who can expand on the detail within the novel to keep the story moving during episodes 3, 4, and 5, where a lot of these bad 1-season TV shows die out.

But I think it’s going to work. Ali is great casting because he looks trustworthy. And I could see him depending on that to gain trust from family, friends, fans. Whereas, internally, he’s the biggest fraud in the world, something you’re typically not expecting with that actor. Remember everyone, one of the best ways to create great character is to make what’s happening inside of them and outside of them as opposite as possible. Success, fame, recognition outside. Shame, fear, feel like a fraud inside. That’s what’s going to make this show work.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is a major spoiler WIL. You’ve been warned. Whoever your “killer” is needs to be treated like every other character throughout the novel/script. Anna, Jacob’s wife, is treated so oddly throughout this story. She’s never around. Whenever she is around, she’s a wallflower. Whenever she talks, she’s very non-specific, vague. Meanwhile, every other character gets a super-detailed life. Anna is treated so differently that we know something is up with her. And, of course, she turns out to be Evan’s sister. She’s the one who’s been threatening him. Whenever you have a twist ending, you want to put yourself in the reader’s shoes and ask, “Who would they think the killer is?” Then make sure, whoever they’d think it is, NOT TO MAKE THAT CHARACTER THE KILLER. Not enough writers realistically evaluate readers when they do this.

What I learned 2: What you want to do instead is let Anna (or whoever your version of Anna is) be the disco ball. She’s the pretty shiny thing we’re all looking at over here so you can shock us at the end with that guy/gal we weren’t expecting at all.

Does anyone here know what a “screenplay movie” is?

A “screenplay movie” is a movie that actually resonates because of the screenplay.

Most of the movies at the top of the box office in the IP era are *not* screenplay movies. They’re Hollywood movies.

They’re designed to sell tickets and merchandise. Their impact is based more on the filmmaking – the big set pieces, the flashy production value, the huge star power – than anything that’s written on the page.

It’s not that writing these movies is easy. Far from it. Hollywood movies have their own set of challenges brought on by managing multiple points-of-view (the studio, the director, the actors, 20 different producers), many of which conflict.

Imagine receiving a note from the lead actor to make their character funnier then an hour later receiving a note from the head producer to make the lead character more serious. That kind of conflicting feedback is not uncommon.

But the bulk of Hollywood movies are about laying out a clear three-act structure and managing exposition so that the audience can clearly follow what’s going on. You are solving issues that are more technical than artistic, which is why these movies are less rewarding to work on and less rewarding to watch.

“Screenplay movies” put more thought into the characters, take more risks inside the plot, have more to say through their themes, and generally make you think and feel a lot more. They are designed to connect with you rather than whack you across the head.

Here is a list of the top 10 movies at the global box office in 2023:

1) Super Mario Bros — $1.36B

2) Barbie — $1.34B

3) GotGVol3 — $845M

4) Oppenheimer — $777M

5) Fast X — $705M

6) Across The SpiderVerse — $688M

7) The Little Mermaid — $568M

8) Mission Impossible7 — $552M

9) Ant-Man3 — $476M

10) Elemental — $468.6M

Surprisingly, five of them are screenplay movies and five of them are Hollywood movies. I say “surprisingly” because, usually, the top 10 is dominated by Hollywood movies. Do you know which ones are the screenplay movies? I’ll give you a second to make your picks.

The Hollywood movies on the list are…

Super Mario Brothers

Fast X

The Little Mermaid

Mission Impossible 7

Ant-Man 3

The screenplay movies are…

Barbie

Guardians of the Galaxy 3

Oppenheimer

Across The Spider-verse

Elemental

I know a lot of people loved Super Mario Brothers but let’s be real. It’s positioned as a product above all else. I wouldn’t be surprised if AI is writing all the Fast & Furious scripts at this point, the writing has become so insignificant. Did anybody even write The Little Mermaid? Aren’t they just using the same script as last time? Mission Impossible 7 isn’t as bad as Fast X in the writing department. But that franchise clearly prioritizes stunts over everything else. And then Ant-Man 3 is part of the Marvel machine. They probably have a studio exec leaning over a poor screenwriter’s shoulder saying, ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘rewrite that part,’ after every sentence.

With the screenplay movies, we’ve got Elemental, which I’m guessing is a screenplay movie because Disney puts a lot of thought into their screenplays for their original films, a valuable lesson they learned from Pixar. I haven’t seen Spider-verse but everybody tells me it’s got a great screenplay. I almost put Oppenheimer on the Hollywood list because Nolan prioritizes directing over writing. He’s more about his vision than getting the screenplay right. But he cares so much about these characters, and characters are the most important screenplay ingredient of all, that I decided to give him the benefit of the doubt. James Gunn has always been a screenplay-first guy. And you can tell he wants to move people with Guardians of the Galaxy. He doesn’t just want spectacle.

And then you have Barbie.

Barbie is an anomaly. It is a screenplay movie in a Hollywood movie body. Which is why, even though I didn’t agree with its message, I commend the writers for what they accomplished. Cause what they accomplished is amazing. They made a billion-dollar movie that actually makes you think, that actually gets people talking.

I told you, when I went on my recent family reunion, everybody in my family had an opinion about Barbie. That’s so rare these days. But it’s because the movie is a “screenplay first” concept that it’s resonating. It’s trying to say something rather than trying to draw audiences in. It just happened to be a product that everyone wanted to see. Which is how they used to make movies. They’d make gambles like this.

And for those of you who are saying, “Carson… blah blah blah… it’s Barbie. It’s international IP. Everyone was going to see this no matter what.” I don’t agree with that. I think if they went with the Hollywood version of this, it would’ve looked flat. It would’ve looked uninteresting. It would’ve still made money. But it would not have come anywhere close to 1.3 billion.

“Barbie” should be encouraging to every screenwriter out there. It shows you that when a good writer has a strong vision, they’re better at this than all the studio heads combined. The artist is the only one in the equation who wants to take risks. The studio and the producers hate risks. Which is why the movies they spearhead feel so average. They never hit you on an emotional level.

Here is this latest weekend’s Top 10 along with their categorization…

1) Gran Turismo – 17.3 mil/17.3 mil – Hollywood

2) Barbie – 17.1 mil/594 mil – Screenplay

3) Blue Beetle – 13 mil/46 mil – Hollywood

4) Oppenheimer – 9 mil/300 mil – Screenplay

5) Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem – 6 mil/98 mil – Hollywood

6) Meg 2: The Trench – 5 mil/74 mil – Hollywood

7) Strays – 4 mil/16 mil – Hollywood

8) Retribution – 3.3 mil/3.3 mil – Hollywood

9) The Hill – 2.5 mil/2.5 mil – Screenplay

10) Haunted Mansion – 2 mil/62 mil – Hollywood

I was rooting for Gran Turismo and happy for its first-place finish. Even though it’s a subdued winner, it should get director Neil Blomkamp another directing project. Whether that’s a good or a bad thing, we’ll find out. But a part of me still roots for him, at least until we get District 10. The movie just couldn’t overcome its benchwarmers status. The cast (Orlando Bloom?) makes you think that someone at Netflix made a mistake and accidentally put the movie in theaters instead of on the service.

Poor Blue Beetle. These DC movies can’t overcome their association with the former era of DC. Who wants to see a superhero movie that they know has no future? But even if that wasn’t the case, the CGI on this Blue Beetle guy screamed “cheese factor 700 thousand.” It just didn’t work. It was an ill-conceived superhero project from the outset.

The movie I was most intrigued by on this list was Strays. Not because I wanted to see it. But because it’s a physical manifestation of how confused Hollywood is right now. It used to be that if you pitched a movie like this in a room, the response would be: “A movie with real dogs that’s raunchy and R-rated? So you can’t bring kids, cause it’s too raunchy. And you can’t bring in adults because adults don’t want to see a movie about dogs on an adventure. Who’s going to show up to this movie???” The pitch would die before the writers could ask if the studio preferred two brads or three on their drafts.

But, these days, nobody knows what’s going to do well or not so they throw stuff at the wall. On some level, I admire it. It’s a bold move. But, in the end, it turned out the old school thought process was correct. This concept actively discourages both ends of the audience spectrum from seeing the film.

I’m just glad that, after looking the box office up and down this week that screenwriting still matters! I don’t know why I thought it didn’t matter at the top of the box office. I guess I assumed that the top 10 movies were always going to be machines that placed screenwriting at the bottom of the priority list. But it’s clear from Barbie’s success (as well as some of these other giant films) that if you want to really connect with audiences, giving screenwriters a concept and “getting the f**k out of the way,” a la Michael Jordan circa 1989 in Cleveland, is the best way to go. :)

One of the more controversial new screenwriters on the scene comes at us with yet another one of his high concept ideas

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: (from Black List) When her domineering director makes her film the same scene 148 times on the final night of an exhausting shoot, actress Annie Long must fight to keep her own sanity as she tries to decipher what is real, and what is part of his twisted game.

About: Screenwriter Collin Bannon routinely makes the Black List. He’s done it again here, as this script finished with 12 votes on last year’s list, the unofficial compilation of the “best screenplays in Hollywood.”

Writer: Collin Bannon

Details: 109 pages

Scarjo for Annie?

Scarjo for Annie?

All right, now that we’ve got all of that conflict out, let’s take things down a notch and review a screenplay about going crazy!

I remember reading these stories about Stanley Kubrick forcing Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman to do a million takes on Eyes Wide Shut and how Kidman, in particular, almost went insane.

Then later, probably because he was inspired by Kubrick, David Fincher did the same thing to his actors. I remember Edward Norton being particularly thrown by the first scene he shot for Fight Club. Norton thought he did a pretty good job on take one. But Fincher ended up making him do 20 more. And not just doing the takes, but not giving any direction. I got the feeling from Norton that it was a bit of a mind f—k.

I think the idea of tons of takes is to strip the acting away from the actors. And just have them “be.” I’m not convinced it works. I guess if a scene requires you to look emotionally spent it might work. But it’s hard to give when you’ve been told you’ve failed 27 times in a row.

So I thought building a movie around this concept was cool. It’s also a unique way into a loop narrative. Whenever you can exploit a trend in a way that doesn’t feel like the trend, I always give writers props for that.

It’s 1981 and we’re filming an elevated horror movie (Think The Exorcist, not Friday the 13th) in the middle of some eastern European country. At the start of the script, Annie, our hero, is at her wit’s end. They’ve filmed the entire incredibly intense movie. There’s only one scene left. And Annie is desperate to finish so she can get home for her cancer-stricken mother’s surgery.

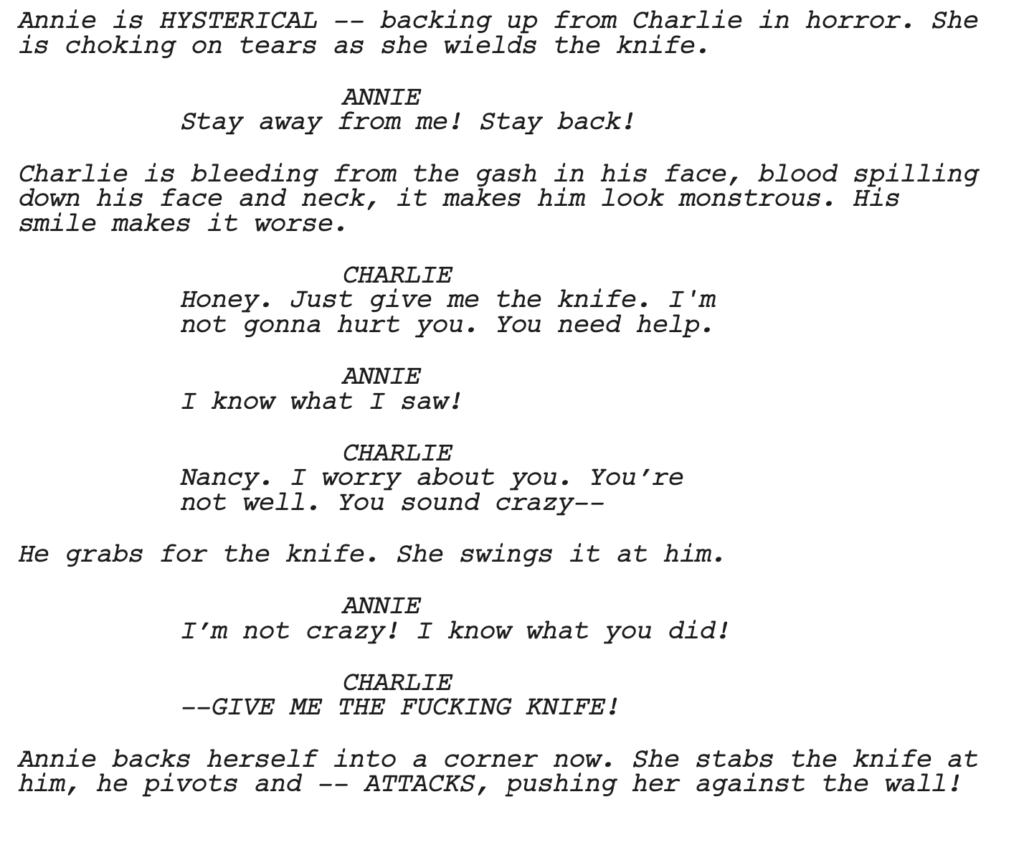

There’s one man in the way, though. Howard Bloch. I could get detailed about who Bloch is but just think: Stanley Kubrick. The final scene in question has Annie’s character fighting with her husband in their bedroom, who she seems to suspect did something terrible – maybe even murdered someone. Annie is screaming at him that she’s not crazy, she knows what he did, which leads to a physical altercation.

Every time they shoot the scene, Bloch says, “Let’s go again.” Annie asks what changes he wants but he never answers her. He just says, “Let’s go again.” That alone would drive a person crazy. But to make matters worse, everyone on set seems to hate Annie, who, by the way, is the only woman on the entire production (this is 1981 remember). So she feels super isolated outside of her assigned personal assistant, Laszlo, who’s a sweetheart.

As the night turns into day, and 1 take turns into 20, then 50, then 70, Annie really starts to lose it. She’s convinced the eye-patch that the DP wears has switched eyes. She thinks the wallpaper in the bedroom has changed color. The photo on the wall of her character and her co-star’s character turns into a photo of her and her mom. She repeatedly sees her mom in the back of the set. She thinks one of the stunt doubles wants to assault her.

Then the worst imaginable thing happens. The hospital calls and lets Annie know that her mom passed away unexpectedly. Bloch apologizes profusely. He tells Annie that he’ll get her on a flight home immediately. But now Annie is determined. She asks Bloch if he got the take. Bloch confesses he did not. “Then let’s go again,” she says. It’s clear that nobody’s leaving until they GET THIS TAKE RIGHT.

The byline of this post is, “yet another high concept idea.”

Since I know “high concept” can be confusing, I want to explain why this idea is high concept. The best way to do so is by showing you what the “low concept” version of this idea looks like.

The low concept version of this is the aftermath of an actress who’s had a long day after trying to film a scene that wasn’t working. We see her depressed and struggling and maybe her boyfriend has to build her back up again for the next day. Another version would be an actress trying to make it through a tough production in general. Every day is a challenge and she’s beaten down by the process.

In other words, straight-forward boring explorations of what it’s like to be an actress on a difficult shoot.

The second you make it 150 takes, the whole concept takes on an elevated feel. It feels bigger. It’s more intriguing. This is what makes the concept “high,” is the clever elevation of the common interpretation of an idea.

But what about the execution?

I’m, self-admittedly, not a fan of descent-into-madness screenplays for one simple reason. The screenwriter never gets the line right between keeping the script understandable and the story crazy. They always bring the craziness and messiness into the writing itself so we’re not sure what’s going on. These scripts have to be understandable even if what’s going on in the story isn’t supposed to be understood.

That’s a hard balance for even experienced writers to master.

While Bannon’s tackling of the problem isn’t perfect, he does a pretty good job. He definitely captures this character’s insanity but I still, usually, understood what was going on. I think the reason he was able to do this was because he kept the story simple.

Literally, we’re on the same set filming the same scene over and over again. So when there are crazy elements like, say, a mysterious woman that nobody else can see walking around in the background, we’re able to identify that as the lone variable that has changed and therefore an extension of Annie’s psychosis.

Plus, Bannon added some smart elements to his screenplay that exploited the idea. For example, at one point, Annie’s P.A. accidentally lets out that Howard has been telling everyone on set to be mean and isolating to Annie so he can get the performance he wants out of her.

There’s also mystery elements. The hospital calls to inform Annie that her mother passed away. But we’re immediately questioning, did that really happen or did Bloch make that up in order to get a better performance out of her? So now we have this carrot dangling in front of us, pushing us to keep walking, cause we want to know if her mom really is dead or not.

In other words, it isn’t just about doing the scene over and over again. There are other unresolved threads. Thank God for that because the movie would not have worked if that was the only thing propelling the narrative. Lots of newbie writers would make that mistake, by the way. They’d only focus on what’s in the logline – the bare-bones interpretation of the concept. But movies are too long for that. You need to keep feeding the beast – the beast being the reader – new meals every ten pages or so to keep them interested.

The irony about this script is that if it was ever tuned into a real movie, it would have the exact same effect on the real actress who took the part. She would be shooting 300-400 takes of the same scene. Cause she’s shooting multiple takes to get each of the takes right within the story itself. You’d have to be crazy to volunteer for that. But maybe that’s the point.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Your most clever dialogue lines are going to stem from YOUR CONCEPT. Your concept is the primary generator of all that is unique within your script. So if you want to write clever lines, lean into the concept. For example, early on, the hair and makeup guy comes up to Annie before she’s about to shoot her scene and he says, referring to her exhausted face, “Are those dark circles mine or yours?” Annie responds, “I think they’re mine.” “You make my job easier every day.” So, why is this a clever line? Cause the obvious line is, “You look like s—t. We need to get you back in makeup pronto.” That line contains the exact same sentiment, but is on-the-nose and, therefore, boring. A compliment that’s actually an insult delivered in a way to make the heroine feel bad about herself – that’s good writing.

Tomorrow is the deadline for logline entries in March’s LOGLINE SHOWDOWN! We’ve already found one great script through Logline Showdown. Let’s find some more! Submission details are inside this linked post.

Genre: Horror

Premise: A promising first-round draft pick is invited to train at the private compound of the team’s legendary but aging quarterback. Over one week, the rising star witnesses the horrific lengths his hero will go to to stay at the top of his game.

About: This script finished number 13 on last year’s Black List. The writers wrote a successful podcast called Limetown, which they were able to parlay into a TV production for Facebook. That show would star Jessica Biel.

Writer: Zack Akers & Skip Bronkie

Details: 119 pages

Jake G. for Connor??

Jake G. for Connor??

I had my eye on this script as soon as I saw the logline on the Black List because I find sports mortality to be an interesting subject. In order to be a professional athlete these days, you have to start playing at the age of 5 and train 3+ hours a day for the next 30 years of your life. In other words, it isn’t just part of your life. It *IS* your life.

And then one day, the train stops rolling. You’re 35, 36, 37. You still have your ENTIRE life in front of you yet you have no context for how to live it. The only thing you’ve ever known is to practice and play. It’s the reason Tom Brady retires then unretires immediately afterwards. It’s the reason Michael Jordan played for the Washington Wizards. They realize that this is the last time they’re going to get a chance to do this.

So to build a story around a character like that immediately gives you a compelling character study. Which is one of the key components that needs to be there in order to write any movie under 100 million bucks. Stories should be about struggle. Not just the external struggle. But the INTERNAL struggle. You want your characters fighting something inside of themselves. If they’re not, there’s a good chance they’ll come off as bland.

The real question here though is, can a movie in the sports genre be a straight-up horror film? That’s what I’m going to try and answer by the end of the review.

Connor Dane is 44 years old and has won six Super Bowls for the Dallas Cowboys. And he doesn’t seem to be slowing down. But the Cowboys are realistic. At some point, there’s going to need to be a change at the quarterback position. And they don’t want to get caught with their tight little football pants down. So they draft the guy everyone thinks is going to be the next Connor, Benny Mathis.

Everyone’s shocked when the Cowboys trade up for Benny. But what’s even more shocking is that Connor calls. He tells Benny that he wants him to come work out with him for five days at his Vegas home. Benny’s handlers think it’s some kind of trap. But what’s Benny going to do? Say no to the greatest quarterback ever and his new teammate?

Benny arrives at the giant compound in the middle of the desert and is alarmed with what he sees. Connor lives in one of those Kardashian type homes. The ones with excessively sparse surroundings. How sparse? Connor doesn’t even have doors! There are doorways. But no doors!

After an intense first day of workouts, Benny hears wild screaming in the middle of the night. He also finds a sheep hanging around outside his bedroom window. Oh, and his bathroom sink is also filled with blood for some reason. When Benny shares these things with Connor, Connor seems aloof. He says not to worry. His handlers will take care of it.

After Connor leaps out of his swimming pool in a single bound, Benny starts sensing something is up. He goes on a trek into the desert and finds a shrine in an old church that has both all of Connors’ achievements pasted to the walls and HIS OWN achievements.

The caretaker pleads with Benny to ask for a night off from Connor and then takes him into the city. At a dance club, he tells Benny that he needs to get out of here. Then Benny sees Connor in the crowd dancing! But it’s not Connor. It’s 20-years-younger-Connor! What the heck is going on??? We eventually learn that Connor may be calling on forces more powerful than our own to achieve the amazing career he’s had. And that he wants to pass that power on… to Benny.

I think it’s cool when writers mash up genres that don’t normally go together. Cause you’re guaranteed to get something different. With that said, there is a risk in making untested creative choices. Because, usually, if you’ve never come across something in the creative world, it’s because it’s been tried and failed badly.

This is probably the case with combining horror and sports. I’m just not seeing any evidence that these two genres can harmoniously co-exist. The biggest problem is that the people who come to these genres come to have a very specific experience. If you’re a sports nut, you want to see that great sports movie. If you’re a horror guy or gal, you want to be scared.

That means every time a scare happens, the sports people are angry and every time competition happens, the horror people are angry.

But the problems in GOAT go deeper. The entire movie is one giant setup for something that we pretty much figure out by page 20. We don’t know exactly what’s going on with Connor. But through the process of elimination, we know there’s some supernatural reason he’s been able to stay good for so long. He probably made a deal with the devil. And, lo and behold, that’s what happened.

I’m not kidding when I say that every single scene in the movie has Connor doing something weird, the subtext being: “Connor’s not normal! There’s something not normal about this guy!” Giving us 30 different variations of that message does not pique our curiosity. Cause we’ve already figured the reveal out. Now we’re just waiting for the writer to catch up with us.

That’s the worst place you can be as a writer. That the reader is waiting for you to catch up with him. You should always be ahead of the reader UNLESS you’re deliberately trying to trick them, in which case you let them THINK they’re ahead of you, only to pull the rug out from under them, which is one of the more fun things you can do in storytelling.

In other words, you would have all these setups towards Connor having made a deal with the devil, and then you’d throw a 180 at us and give us a payoff that we missed because we were following those deliberate bread crumbs pointing us towards the devil deal.

I also wanted more out of the scenes themselves. Every scene felt “first-choicy.” What does that mean? It means that if 100 people wrote this script, 95 of them would’ve also chosen the same scene you wrote. So if you have a scene – like this script did – of Benny lifting heavy weights and Connor being his spotter. That’s a scene 95 out of 100 writers would’ve chosen. It’s low-hanging fruit.

That’s not to say “don’t do it.” The scene has potential. Connor literally holds Benny’s life in his hands if he chooses to move away from the bar at an inopportune moment. But at least try to find some spin on the scene so it doesn’t go exactly as expected. This script wasn’t doing that. It was always giving me the version of the scene I expected.

The script has its charms, though. I love the spec-y nature of it. Contained time frame. Low character count. Organic heavy conflict between the leads. Urgency. And the genre element makes it easier to sell. I was into all that. But the execution felt too basic and repetitive. Very repetitive. For that reason, I can’t recommend the script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the mistakes writers make is assuming that just because the reader doesn’t know EXACTLY what the big reveal of their script is going to be, but still has a pretty good idea, that they’ll be eager to keep reading. We don’t need to know your twist ahead of time to get bored. We only need to have a good idea of what it’s going to be. That’s the mistake this script made. It put everything on the reveal then proceeded to use every scene to tell us what that reveal was likely to be. There needed to be way less repetition here. And there needed to be more misdirection. This script could’ve benefited from moving the “deal with the devil” reveal up to the midpoint. Because that way, we have no idea where your script is headed. Which would’ve made things a lot more interesting.

From the creator of Deadpool comes a 2 million dollar spec sale from the 90s that was supposed to be the next huge Will Smith franchise. What happened??

Genre: Action/Adventure/Supernatural

Premise: A mild-mannered campaign worker receives “the mark,” a special ancient marking that gives him all sorts of special powers.

About: This was supposed to be a huge one. The script was purchased in the 90s for 2 million bucks. It was going to star Will Smith. None other than Steven Spielberg was going to direct. Smith’s Independence Day producers, Devlin and Emmerich, were set to produce. And, oh yeah, it was written by the co-creator of Deadpool, Rob Liefeld. Scripts don’t come with much more pedigree than that. According to Liefeld, the project fell apart because of merchandising and producing points. Although something tells me it fell apart after someone read this draft.

Writer: Rob Liefeld

Details: 1997 draft

The Matrix.

Wanted.

National Treasure.

Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The Devil’s Advocate

The script has it all.

In many ways, this project was the pinnacle of the 90s Hollywood deal. You had this sexy high concept idea. You had mega-star Will Smith. You had Spielberg joining you in the pitch room. Let’s be honest. They could’ve pitched “Bathroom Boy: The Tale of the Lost Toilet Paper” and sold it in the room that day.

But instead they sold The Mark.

And we’re all left to wonder if this was the final nail in the coffin for giant script sales. Cause this script is awful.

We start in Nazi Germany during World War 2 cause of course we do. Some evil German commander named Gates is storming into a Jewish apartment building to find the Jewish man who holds “the mark” on his hand – a special tattooed stamp that means you have powers!

The elder owner of the mark passes it down to his son, Jacob, who then leaps across buildings in a single bound, escaping the evil Nazis, as well as escaping the boring scene.

Cut to modern day and you bet your bottom dollar we got a New York apartment that’s got dirty clothes on the floor, that’s got beer cans on the side table, and, woudln’t you know it, when the alarm clock goes off, a hand shoots into frame and throws against the wall.

Apparently Chat GPT time-traveled back to 1997 and answered the question, “How do I write the most cliched character introduction ever?” And that’s what it came up with before traveling back to the future.

The cliched hand belongs to Mike Collins, who gets a knock on the door soon afterwards and do I even need to tell you who it is? Cause if you don’t know, you’ve never seen a movie before. It’s the landlord! And she wants her money. Cause Mike is late with the rent.

Mike makes an excuse then meets his elder friend, Jacob, by the news stand – yes, Jacob is the same Jacob from before. Jacob tells Mike to bet on the Bulls against the Knicks if he wants to make some money. Mike heads to his campaign job where the mayor is going to be running for president soon. At the end of the day, the Bulls beat the Knicks.

Mike goes to thank Jacob except Mike finds Jacob shooting balls of energy out of his hands at two dudes in the alley. Jacob gets hit by a enemy energy ball and, as he lays dying, PASSES THE MARK TO MIKE! Mike runs away, realizing, in the moment, that he has super speed. And then he also has super strength.

He’s terrified of all this new power and he tries to hide. But he’s soon visited by this chick named Falkon. Falkon then takes Mike to her secret hideout which is in…. Wait for it, the Statue of Liberty. Falkon explains to Mike that he now bears the “mark” and, therefore he’s “the one” and that the evil Jonathan Gates (from the opening) is going to do everything in his power to get that mark because the planets are aligning soon and he needs to have it do destroy the world or something. Yada yada yada. The end.

The Mark may be one of the most blatant examples of how influenced we are by the time that we’re writing in. This was written squarely in 1997 when everyone was writing these scripts.

You’ve got the nobody everyman protagonist. You’ve got the special power that’s passed on from generation to generation. Our character is known as “The One” (although, in the writer’s defense, Matrix hadn’t been released yet). You’ve got Nazis. You’ve got the “learn your powers” fun-and-games section.

I love reading scripts like this for this very reason – to remind you not to write the same stuff that everybody else is writing at that time. You have to be able to step out of your body, travel 20 years into the future, and look back at your current script through that lens of, “Does my script read like every other movie that was being released at that time?” And if the answer is yes, your script either needs a major overhaul or to be thrown in the trash.

I always say that a screenwriter becomes a screenwriter when they watch other movies and don’t think, “Ooh, that’s cool, I’m going to include that in my script,” but rather, “Ooh, that’s cool, now I can’t use that in my script.” You learn to actively avoid the things that everybody else is doing.

But let’s play a different game for this review. Which is, if I read this in 1997, would I like it? And the answer to that would be no. I’ll tell you why. Because the secret base is in the Statue of Liberty. Let me repeat that: THE SECRET BASE IS IN THE STATUE OF LIBERTY!!!

I have seen many a questionable writing choice in my day. I’ve seen scripts written entirely on one’s cell phone. I’ve endured twenty-minute scenes of characters watching The Shining… IN SPACE. I’ve read not one, not two, but THREE Mattson Tomlin scripts, which, combined, exhibited the thoughtfulness and sophistication equivalent to a fifteen minute visit to the bathroom.

But giving your characters a secret base in the Statue of Liberty in a non-comedy is up there with the dumbest creative choices I’ve come across. I’m not even sure Mattson Tomlin would do something this dumb. I mean, are you even trying at that point?

As soon as that happened, I was out. The script was trending downwards before that. That brought it into “bottom of the ocean” territory.

Another problem is that Liefeld adheres to formula so rigidly that it strangles the story’s ability to live. This is a debate that’s raged on for years in the industry and this script shows you why. Because every single beat of this script is lined up with the Blake Snyder beat sheet and, as a result, there’s no life to it.

It’s just a screenplay beat sheet. It’s not a real thing that happened.

Which is what you’re trying to achieve, by the way. You’re trying to make your movie feel like something that really happened. The second we don’t feel that, we start seeing your movie as a produced fake product rather than an experience to get emotionally wrapped up in.

I think structure is good. But it has to be invisible. You can’t be so clunky in your construction of it that all your plot pillars are visible. You have to hide it, like exposition. Which basically means that your characters are dictating what happens as opposed to the writer dictating what happens.

When the Terminator walks naked into a bar and finds a biker his size and tells him to give him his clothes, we feel that as a genuine moment because the Terminator needs to blend in to society. And he can’t blend in without clothes. It’s imperative that he do this to succeed at his mission.

Conversely, when Captain Marvel steals a guy’s jacket and motorcycle who tells her to smile, that moment is 100% created by the writer. It doesn’t need to happen for the story. It’s just the writer wanting to get this thing in there they want to say.

Structure works the same way. If we feel like, “Oh, now we get the scene where the guy gets a tour of the secret base,” and, “Oh, now we get the scene of him practicing his new powers,” and “Oh, now we get the scene where the love interest pops in,” then we start falling asleep.

A script dies the second the reader knows what’s going to happen three minutes from now. Once they can always tell what’s going to happen in three minutes? Your script is dead to the world cause it’s terrible.

You’ll never be able to perfectly hide everything, of course. But you have to be good enough to hide most of it.

To be fair to Liefeld, this doesn’t feel as cliched if we’re reading it in 1997. But it doesn’t matter because there is literally nothing to offset the cliches. Every single choice, from the main character to the love interest to the powers to the rules, are so insanely bland that I don’t know how he was okay with others seeing these pages.

Try.

At the very least, try.

That’s all I ask from writers. Let me see that you’re trying and, even if you write a bad script, I will respect you for giving it your all.

This script had zero try-factor.

And you can read it yourself! – The Mark

[x] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s a famous moment in the movie National Treasure where Nicolas Cage’s character has to use the Constitution, which is encased in bullet proof glass, to deflect some bullets. The reason this moment is so famous is because it’s ironic. It’s clever. That you’re using this 300 year old document to defend yourself. Having a secret base in the Statue of Liberty is not ironic. And because of that, it comes off as lazy and dumb. So, if you’re tasked with coming up with something and you don’t know if it’s cool or stupid, do the irony test. If there’s some irony there, it’s probably cool.