Search Results for: the wall

With the arrival of today’s spec, we must ask the question, is the real-time war film going to become its own genre??

Genre: Action/War

Premise: Near the tail end of World War 2, an American POW escapes certain death at a concentration camp and makes a run for the southern Allied border, but is pursued by a determined Nazi soldier.

About: Today’s screenplay comes from an interesting writer named Henry Dunham. You might recognize the name because I reviewed a previous script of his called, “Militia,” which was a clever take on the contained thriller genre where a rural militia are forced into a local warehouse to figure out who’s responsible for a rapidly growing series of domestic terrorist attacks. The film was too dark for most to handle but I never forgot the writer. Well, he’s back and he’s teamed up with Thunder Road, who are responsible for John Wick, Sicario, and The Town. It looks like Dunham will be directing his script as well.

Writer: Henry Dunham

Details: 96 pages

This is one of the best sub-genres to get into right now. The fast-paced (or high-concept) simplistic major war sub-genre. We just saw this with 1917. We saw it with Black List script, “Helldiver,” about American and Japanese war pilots stuck in the middle of the ocean on one of their shot down planes. We saw it with the number one Black List script of 2017, Ruin, about a former SS Captain and a Jewish woman who travel through war-torn Germany to find and kill a Nazi officer.

Not many possess the skill required to create rich nuanced screenplays about complicated wars. But that’s okay. You can still come up with a simple easy-to-understand concept that plays within World War 1 or World War 2 and knock our socks off. And that’s what we get today.

It’s winter. American soldier Alfred Bergen is in some sort of Danish concentration camp near the end of World War 2. When we meet him, he’s being rounded up with the rest of his POWs by a hurried German army. They’re ditching this camp, and therefore everyone needs to be killed. They take the Americans, line them up, and shoot them all dead.

Alfred wakes up in a mass grave. He survived somehow. And, as luck would have it, the Germans are gone. So he squeezes out, grabs some food in one of the buildings, and finds a map on the wall. 50 miles down is the Allied line, in Luxembourg. If he can get there, he’s golden.

But first Alfred must grab warmer clothes and dog tags from his dead friends. While he’s doing this, new Germans roll up. Alfred makes a run for it into the endless Southern forest, but a perceptive Nazi soldier named Otto Ziegler notices the footsteps in the snow and goes after him. Alfred has a few hours head start but Otto has a horse.

Alfred survives the night but then runs into another German unit. Germans in front, Germans behind! Alfred discovers a nearby clearing where an Allied unit has been slaughtered. So he sneaks over and plays dead amongst the soldiers. Except there’s a problem. The clearing isn’t land. It’s a frozen over lake. So when Otto discovers him and starts shooting, it’s cracking the ice. Alfred goes under, swims underneath the ice to the southern shore, and is back on the run.

He eventually makes it to a farm where a young Danish woman is living. She doesn’t believe he’s who he says he is and tells him to leave. He explains if he does that, the evil Nazi following him will surely come here and kill her for aiding him. Their only shot at surviving is to stand their ground in the house and kill Otto. So they prep. Otto will be here soon and they need to be ready. Little do they know, this mano a mano battle is far from over.

So here’s the thing.

When you’re writing something that’s action based – something that doesn’t have a lot of dialogue, you need to write in a stripped-down minimal format that’s as fast to read as possible. The reason for this is that readers like dialogue. Why do they like dialogue? Cause they’re big fans of the artistry of conversation? No. Because dialogue reads three times as fast as action.

So when all you have is action, the read is much longer. Which means the reader hates you. Not literally but kind of, yes, they do. Your script might be your baby but to them it’s time taken. You are taking time from them. Readers are fine with this when you respect their time. But if you try and write some all action all description script and don’t keep the action lines short, the reader will want to kill you.

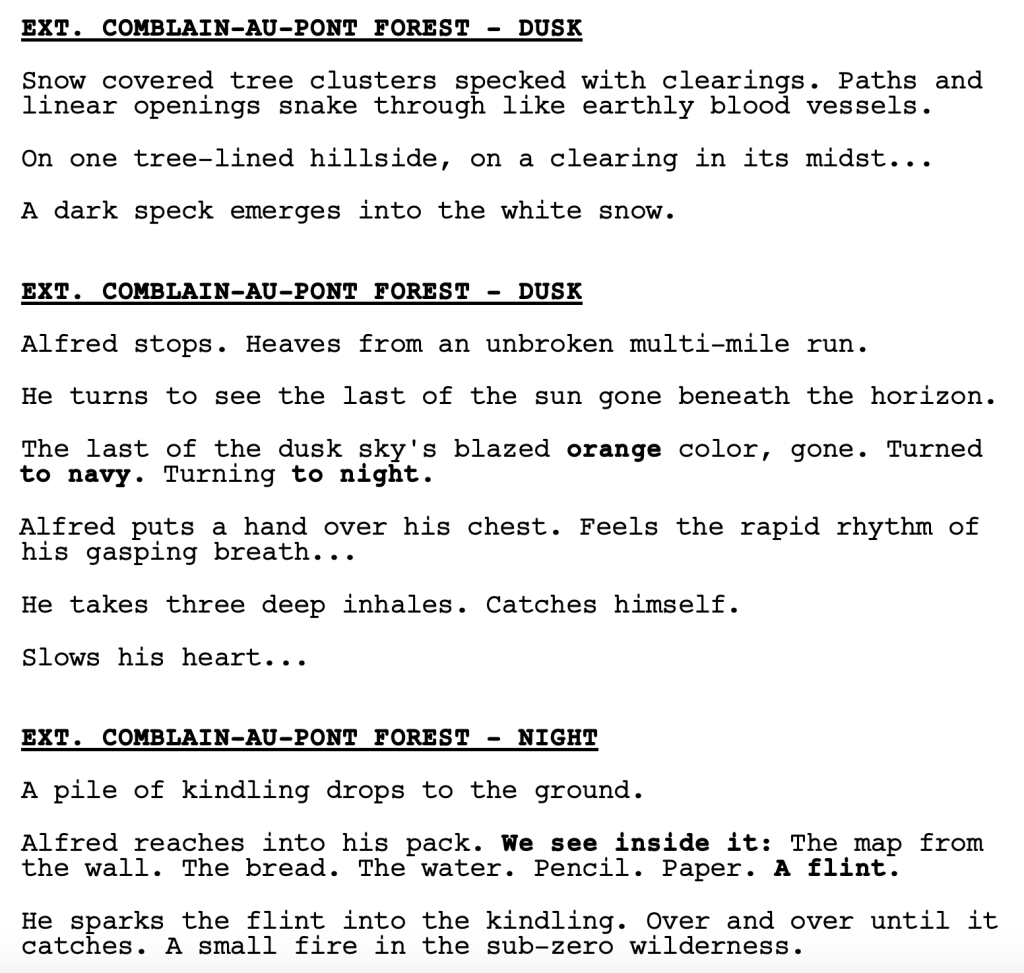

I don’t think there’s a single paragraph in “Perdition” that’s over two lines. And while that might seem like overkill, that’s how you should be thinking when you have minimal dialogue.

Speaking of dialogue, our first scene with dialogue doesn’t happen until page 35. It took me a moment to figure it out but I realized that this scene was pulling double-duty. It wasn’t just providing a conflict-filled scenario between our hero and a skeptical home-owner. It was answering a few big questions we had.

The first one was why Alfred was so obsessed with these freaking dog-tags he was carrying around. You’d think they were newborn puppies he was so protective of them. The second was why the heck is this man chasing you? Doesn’t he have better things to do than follow a random American trying to find safety?

I bring this up because this is one of the most common challenges you’ll face in screenwriting. You’re trying to make a scene look like it’s only there for entertainment value when, in reality, you’re using it to slip in relevant exposition. The writers who do the latter but make it look like the former are the ones who are usually the most successful.

Luckily for Dunham, this is a naturally entertaining scenario. You’ve just snuck into someone’s house. They found you. They have a gun trained on you. They know they must doubt everything in order to survive. So when the woman, Louise, starts interrogating him, it’s only natural that she asks him the same questions we’ve been wanting answers for. Why the heck do you care about a bunch of pieces of metal? Why would some psychopathic soldier follow you all the way across the country? Hence, we don’t realize that exposition is being given. But that’s the catch. You need to create scenarios that hide exposition within entertainment. As long as we’re more focused on the tension or the intrigue of the moment, we won’t catch your sleight-of-hand exposition drops.

So what rating do I give this script?

I believe when a script poses a premise to the audience, it must deliver on two promises. The first one is to deliver on the promise of the premise. If you tell us your movie is about dinosaurs on an island, don’t give us a political story about land rights.

The second promise is to deliver something above and beyond what we expect. If you only give us what we’ve imagined in our heads, why did we need you? We could’ve imagined that ourselves. A professional writer must go above and beyond the call to give us MORE. More could mean a major plot twist we weren’t expecting or it could mean amazing characters that were authentic and interesting and made us feel something.

“Perdition” definitely delivered on the first. And it just barely delivered on the second. There were enough strong moments that I found myself excitedly turning the pages. I loved, for example, that our hero finds safety in a sea of dead soldiers. But that the safety is an illusion. He’s on a frozen lake. And with every gun shot that comes his way, that ice is cracking. Stuff like that put this over the ‘worth the read’ edge for me into ‘double’ territory.

I also like that the ending here is NOT what you’d expect at all. AT ALL. Yet it’s somehow immensely satisfying. I don’t want to spoil it but it’s got “movie moment” written all over it.

I could see this being marketed as the WW2 version of 1917 and making a lot of money.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: We had three different stories this week. A horror movie. A heist film. And a World War 2 flick. Coincidentally, all three of them had soldier stories. I used to think anything involving soldiers (especially backstory) was cliche. Everyone uses it. But I came around to it when I realized there are no higher stakes than war. War is where every moment is life or death. So if you can tap into the most extreme component of humanity – survival – why wouldn’t you? You still have to come up with scenarios that feel specific and authentic for your soldier story to resonate. But when it’s done well, it most certainly feels bigger than your average character drama.

DEADLINE FOR THE LAST GREAT SCREENPLAY CONTEST IS JULY 4TH!!! JUST 10 DAYS AWAY!!!

This is the 3rd in my line of “How to Win The Last Great Screenplay Contest” articles. You can read the first one, on dialogue, here. Last week’s, on character, here. Today we’re going to talk about the second most important part of your screenplay: the ending. Or, to be more specific, the third act.

Why is this the “second” most important part? Because the first 10 pages are the most important part. If the reader doesn’t like those, it doesn’t matter what your ending looks like, cause they’ll never read it.

The reason I’m talking about the third act with just 10 days to go is that it is probably the section you’ll be spending the most time on. The first act of a screenplay gets the lion’s share of a screenwriter’s time. I’d guesstimate writers put 50% of their efforts into the first act, leaving only 50% for the second and third acts!

The third act, being at the very end of the screenplay, often gets neglected. And since it’s critical that your script go out with a bang, you should be spending a lot of your time in the lead up to our deadline making that ending great. For that reason, let’s discuss what you should be doing with your third act.

As a reminder, the end of your second act – which will take place around page 75 of a 100 page script, 82 of a 110 page script, and 90 of a 120 page script – needs to be the lowest point for your hero in his journey. What does this mean? It means that whatever your hero is trying to accomplish, this is the moment where it seems like all hope is lost. If it helps, there’s usually a death involved, if not directly then symbolically.

With Star Wars, it’s Obi-Wan dying. In Toy Story 4, it’s when the antique store doll, Gabby, is rejected by her ideal owner, Harmony. In JoJo Rabbit (major spoiler – WATCH THE MOVIE FIRST!), it’s when JoJo finds his mother hanging in the town square. In E.T., it’s when E.T. dies. In Deadpool, it’s when Ajax kidnaps Vanessa. It’s important in this moment that everything feel helpless, that it feel like there’s no chance our heroes will succeed.

For those of you who think these pre-mandated moments in a script are hogwash, let me explain why you’re doing this. Every movie should be an emotional roller-coaster. You want to bring the audience up, bring them back down, make them laugh, make them cry, make them angry, make them happy. This vacillation of emotion is highly addictive. It’s the same reason people get infatuated with lovers. It’s the ups and the downs and this constant intense emotional flow that you can’t get enough of. The idea with your ending is that you’re going to bring the audience up as high as you possibly can. So it only makes sense that, before you do that, you bring them as low as you can. That is what allows for the largest leap in emotion. The bigger the leap, the more memorable the experience will be.

A lot of people don’t know what to do after the “lowest point.” Well I’ve got good news for you. It’s simple. You give your hero 2-3 scenes to stew in their sadness, to feel sorry for themselves, and then they have a REBIRTH. The rebirth is them realizing that, even though the situation is impossible, they still have to try. They still have to go after the girl, even if she’s leaving for Australia in 20 minutes. They still must fight the bad guy, even if he’s effortlessly beat them five previous times. You still must try and destroy the Death Star, even if it requires a one in a million shot.

From there, what to do should be fairly clear. Your final twenty pages is going to be a mini-movie. You should have a clear goal (save Vanessa), clear stakes (if you don’t, she dies), and urgency (you only have until the end of the day). And, just like your script is divided into three acts, your ending will be divided into three acts.

We need a setup (this is where we set up the hero’s plan), the conflict (this is where the antagonist will try everything in his power to prevent the hero from succeeding), and the resolution (our hero either succeeds or fails).

A couple of additional pieces of advice. Your third act is where you’re going to pay off all your setups. So if you set up your hero as a guitar player and, at the end of the movie, the guitar player at the high school prom breaks his finger and can’t play but the band needs to play the song in order for your mom and dad to dance so that they can kiss on the dance floor, fall in love, get married, and you’re born (Back to the Future), well, this is the moment to pay that off. Marty was set up in act 1 as wanting to be a guitar player so he can stand in for the guitar player in this final scene.

Go crazy with setups and payoffs. As I’ve said here before, the biggest bang-for-your-buck screenwriting tool is the setup and payoff. Unless you completely botch them, they always work.

And, also, just like your script had a “lowest point,” your ending should have a “lowest point.” There needs to be a moment in the final battle, or car chase, or race to get the girl, where your hero fails. And it looks like the movie is over. That should be your goal. To make it look like YOUR HERO HAS LOST. This is the one final EMOTIONAL LOW you’re going to put your audience through so that when they leap up and defeat the villain, we get that goosebumps feeling that you can only get while watching a great movie.

I also want to point out that the more non-traditional your movie is, the harder it will be to institute this formula. This is why so many indie movies run into trouble with their endings. There was never a real character goal. And if there’s no character goal, it’s hard to know what your character should do at the end. The whole point of creating a character goal is to create a clear final ending where they either achieve the goal or don’t. So if you don’t have that, it can get complicated.

That’s not to say it’s impossible. Just that it’s harder. My advice to you would be to institute this formula as well as you can. And for the parts that don’t fit, follow the emotion. What you’re looking for in a great ending isn’t beating the bad guy. Sure, that’s all well and good. But the true magic of a great ending comes from an emotional beat, usually a character finally overcoming their flaw, or two characters who’ve been at odds with each other the entire movie finally coming together.

A good example of this is JoJo Rabbit. I would implore anybody here who hasn’t seen the movie to go watch it first due to spoilerage. It was my favorite movie of last year (I saw it after I made my 2019 Best Movies List, so it’s not on there). And a big reason for that was the ending, which, it turns out, is non-traditional.

JoJo Rabbit does not have a character goal that drives the film. He’s just living his life, which has been interrupted by the Jewish girl his mother has helped hide in the walls of the house. So a lot of the movie is about the conflict between those two characters.

What JoJo Rabbit did that was smart was it used the end of the war as a framing device to create its ending. Taika still used the “lowest point,” by killing off Jojo’s mother. And then he throws in Hitler’s suicide and the Americans rushing into the city to take out the Germans. This provides our big exciting ending even if our hero doesn’t have a goal to achieve.

And to provide the emotional catharsis that all good endings have, Taika creates two unanswered questions. One with Imaginary Hitler. What will JoJo do now that Imaginary Hitler is insisting he take out the Jewish girl living in his house. And two, what happens with Elsa (the Jewish girl)?

The final scene is JoJo going back to his house and letting her know she’s free. It’s an amazing scene because throughout the whole movie, her life was dependent on him. Now, he’s all alone. He has no parents. Nowhere to go. His life is dependent on her. She’s all he has left. Will she leave him? Or will they go off together?

I’m not going to pretend like endings are easy. But hopefully this has given you some framework to work with so that you can ace your ending. Good luck!

Next week, we’ll talk about what you can realistically achieve in a script with three days before a deadline!

For those not up to date, I’ve moved The Last Great Screenplay Contest deadline to July 4th. That gives us FOUR Thursday articles to get your script into shape so you can win the contest and we can get your movie made and take over Hollywood. Each of these four articles will deal with a major screenwriting component and why not start with everybody’s favorite screenwriting topic: DIALOGUE.

Now we’ve gone over dialogue every which way on this site. I’m not sure I can add anything new. But what I *can* do is talk about some of these things in a more abstract sense. Because let’s be honest. The pursuit of great dialogue has an undefinable abstract quality to it. Nobody’s able to nail down definitive rules that lead to great dialogue. I’m hoping that by exploring some of the topics that influence dialogue, we can get a stronger sense of how to master this elusive part of screenwriting. Let’s get to it.

1) Keep it clean – Yesterday’s script, The Swells, didn’t have the greatest dialogue. But the dialogue was very easy to read. And the thing I noticed was that the writer put as little description between dialogue lines as possible. This ensured that the dialogue flowed effortlessly. When a writer starts interjecting what the characters are doing or how they’re reacting inside a dialogue scene, it slows things down A LOT. This is one of the easiest ways to make your dialogue stronger. Keep your excessive description to yourself.

2) Excavation of Exposition – Exposition is a dialogue killer. And, depending on how excessive your plot is, you could get stuck writing tons of it. So how do you make the dialogue fun to read when you have all this technical plot stuff you have to convey? The answer to this could be its own article. But here’s what I endorse. Do a first draft of the scene with all your exposition in there. Then, every time you rewrite the scene, take away AS MUCH EXPOSITION AS YOU CAN and replace it with natural conversation. Make it sound more and more like people talking to each other as opposed to characters giving readers information. You’d be surprised at how far you can take it. A page-long monologue about what it’s going to take to steal the money might end up being as simple is, “We get in there by sunset, we’ve got eight minutes, then we’re out.” If it feels like there’s even a little bit of talky exposition in a scene, do everything in your power to squash it.

3) Turn off your inner grammar Nazi – A telltale sign of weak dialogue is grammatically correct dialogue. Dialogue that doesn’t have any of the messy linguistic flow of a real-life conversation. The most basic example of this is if a character says, “What is up?” Instead of “What’s up?” This mistake permeates logic-based writers who don’t have an appreciation for how loose and fun language can be. Instead of saying, “Did you and Mary finally make it to your date night reservation on time?” you might want to go with something like, “Lemme guess. Another Taco Tuesday disaster?” Yes, there will be robotic characters who speak in grammatically correct sentences. But if you don’t have one of those, loosen up, dude.

4) Don’t overwrite dialogue – Dialogue is the opposite of description. Description is something you can keep perfecting with each draft and it’ll continue to get better. But when you do this with dialogue, it reaches a point where it starts to feel too perfect. The answers are too clever. The responses are more intelligent than the character who’s saying them. It’s this “crossing the rubicon” moment where the dialogue is so honed that it no longer sounds like the messy splattered world of real-life conversation. You can approach this problem in two ways. The first is to be aware of when you’re doing it. It usually picks up around the 5th or 6th draft. Check yourself. Ask, “Does this sound too perfect?” A second more radical approach is, once you’ve perfected the dialogue of a scene over 5 to 6 drafts, erase the scene altogether and write the dialogue from scratch. The reason this works is because you know the scene so well that you’re much better able to navigate the conversation. And yet, the dialogue still has that messy real-life feel to it since you’ve rewritten it from scratch.

5) Boring dialogue comes from boring characters – Think about it. When has a really interesting character ever spouted out a bunch of boring dialogue? It doesn’t happen. So if you’re struggling with bad dialogue in your script, look at your characters and ask if they’re interesting – if they’re unique and have strong personalities. One of the hardest things to do is to make a bland character an interesting conversationalist. Do a character check. Add personality to the ones who aren’t interesting and you’re going to find that your dialogue becomes a lot better.

6) Pump up the pressure – The things we say usually become more interesting when more pressure is added to the situation. So if you put two characters in a room who have nothing to do but talk, you have zero pressure in the scene. Which is a recipe for bland dialogue. Find a pressure point, push, and your dialogue is going to come alive. Pressure can come from anywhere. It could be the pressure of the walls closing in in the trash compactor scene in Star Wars. It could come from characters being chained to the wall like in the original Saw. It could come from one character needing something important from the other character, which is why interrogation scenes work so well. It could come from the deadly sun constantly being on their tail in Into The Night. Find a pressure point, or two, or three, press in on the scene, and your dialogue is going to start popping.

7) Embrace indirectness – Dialogue is worst when what the characters are saying is exactly what they’re thinking. The trick with dialogue is to look for ways AROUND saying the thing they’re saying. For example, if a wife wants to know where her husband was last night, she could say, “Where were you last night?” Or she could say, “You came home late.” The second one is going to lead to a much more interesting conversation because it’s indirect. Likewise, the husband could respond, “I know I stayed out too late. I’m sorry. I won’t do it again.” Or he could respond, “So this is how you want to start the day?” While there are scenes in movies where characters will have straight-forward conversations, most conversations contain an element of shifting around the information that’s being exchanged. This is what makes conversation interesting, is the human element. It’s the dance. It’s the playful way in which we slither around the topic.

8) Have fun when it’s appropriate – You hear it over and over again. Erase all dialogue that doesn’t move the scene forward. I don’t believe in that. As long as your characters are moving towards something (as opposed to sitting around doing nothing) you can create little pockets of “pointless” dialogue because they’re not pointless if they’re informing us about the characters. I’m reminded of the famous Jules and Vincent scene from Pulp Fiction where they go up to kill a guy. Tarantino could’ve cut to them walking into the room. Instead, he showed us these two shooting the shit before they get to the room. And the reason it worked was because there was no plot to expose. It was just a funny scene of two dudes talking. And we didn’t mind because the characters were MOVING TOWARDS SOMETHING. The mistake all these Tarantino wannabe writers made after Pulp Fiction was they would write scenes like this with characters sitting around doing nothing. The audience is more likely to accept these “pointless” dialogue exchanges when the characters are moving towards some goal.

9) The people in your script are real – This is more of a mindset shift than anything. But if you think of your characters as characters in a story, they will speak like characters in a story. If you think of them as real people, they’re more likely to speak like real people. Let’s say your hero, Nathan, needs to ask his friend, Hank, for money. If you’re thinking of this as a story, you’re going to overthink how Nathan would say the correct lines that both inform the reader what’s going on while keeping the dialogue short and to the point in order to move the scene along as quickly as possible. But if you’re thinking of this as two real life friends, everything that they’d say changes. Hank might sit down and start babbling about the guy at his office who lost his entire paycheck on a pyramid scheme. Their conversation is going to be more free-flowing and realistic, and therefore more reflective of real life. Eventually, you’ll have to cut some of the extraneous “real-life” stuff out to keep the scene focused. But, chances are, you’ll retain enough of these real-life thoughts that the conversation is going to feel more realistic.

10) The way you say it is rarely the most interesting way to say it – That big splashy “we need to hire this writer for a dialogue polish” type of dialogue breaks down to finding creative ways to say common things. Normal is boring. Different is refreshing. In the Black List script, “Get Home Safe,” writer Christy Hall has a Skype scene between her main character, Skylar, and Skylar’s mom. In the scene, the mom asks Skylar if it’s okay to post a link to her band. Skylar says of course, you should’ve done that already. Her mom replies, “But you get mad at me when I post stuff without telling you.” Skylar then clarifies what things her mom posts that make her mad. For this, I want all of you to go in the comments section and write out Skylar’s frustrated dialogue response to her mom that explains the things she gets upset about that her mom posts to social media. Then, I want you to come back here and read what Christy Hall wrote. Because it’s going to show you the difference between weak and strong dialogue. Here’s Skylar’s reply in the script: “I only get mad when you post a photo of me deep-throating a burger on the Fourth of July, when I’m on my period, in a bikini, and looking like a friggin’ house, Mom, there’s a huuuuuuge difference.” There’s a ton to get into as to why this is such a strong line of dialogue. First, “deep-throating” is a way more interesting way to say “eating.” So already, she’s separated herself from the screenwriter pack. Next, we get the very specific DETAILED response of Skylar not liking period bikini pictures. That’s a place a lot of writers would be scared to go or not even think of. It feels specific. It feels unique. Skylar does not say “fucking.” She says “friggin.” It’s a small difference, but it’s one more slightly unique element that helps the line stand out. Finally, she doesn’t use proper sentence structure at the end. “There’s a huge difference” should be its own sentence. But by using a comma instead of period, it conveys the “all said in one breath” nature of the response, which mimics how it would sound in real life. Even the detail of using “huuuuuuuge” as opposed to “huge,” adds flavor to the line that further differentiates it from your average line of dialogue. This is an A+ level dialogue line. You achieve this by looking for different ways to say common things. You’ve got to tap into that creative spot of your brain to find this stuff and level up your dialogue.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A young woman invites people up to her remote lake house to murder them. But when a back-stabbing ex-friend apologizes for her past transgressions, our murderess changes her mind, to unexpected results.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List with 8 votes. Rachel James recently graduated from Columbia University School of the Arts. Her previous script, Big Bad Wolves, was a semifinalist in the Nicholl contest.

Writer: Rachel James

Details: 99 pages

Today’s script attempts to pull off that rare feat of dividing its narrative into two completely different parts. In terms of screenwriting, it’s as big of a gamble as you can take.

But if it pays off, terms like “genius” are thrown around. People respect writers who take big chances, who try different things. So did Rachel James pull it off? Let’s find out together.

30-something Lola is up at her remote New Jersey lake house with her father, Don. We’re told that both of them are inherently angry people. Although they seem to be having a nice enough time together.

That all changes when Lola starts hearing a sardonic “sawing” noise which seems to be egging her on to do something. Lola asks her dad about a friend of his who used to babysit her. The implication is that he did something bad to Lola. The next thing we know, Lola has killed her father off-screen.

Lola then invites up an old boyfriend, Art. After they have sex, she kills him too. She seems to have some sort of homicidal bucket list. Which is why, after Art, she invites up her meanie ex-friend from college, Michelle, who stole her high school boyfriend, Chase.

Lola is all set to kill Michelle but then Michelle, ignorant to Lola’s plan, profusely apologizes for stealing her man and marrying him. Lola then decides that she’s not going to kill Michelle, and the two begin a long weekend together where they play question games like, “Who would you murder if you could?”

As Michelle becomes hip to the fact that Lola isn’t being honest with her, she hurries the defense off the field so the offense can play. Not only that, but Michelle inserts herself as QB, and the call is to kill Lola. Or, at least, I think that’s the call. Because the next thing we see is Michelle back at her bougie New York apartment with Chase. This happens at, roughly, the midpoint.

From then on, we follow Michelle, who starts hearing the same “sawing” noise that Lola heard. During a house party that includes a group of people who hold up Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop as the definitive accomplishment of the Western world, Michelle loses it, goes home, and starts draping the walls in her own blood.

When Chase finally comes home, Michelle invites him into the den, turns on some hard metal, and stabs him to death. As this is happening, the name “Michelle” occasionally is replaced with “Lola,” leaving us to wonder if that was a mistake or intentional. Many Black Swan vibes here. Is Michelle Lola? Is Lola Michelle? Was there ever a Lola? I have a feeling that nobody will agree on the answer. Which is either why you’re going to love The Swells or hate it.

What about me? Did I love it or hate it?

I’m not sure what I think.

It’s definitely different.

I admire the bold choice to perform the Split In Half Screenplay. I’m a proponent of making the second half of your script different from the first so that it doesn’t repeat itself. I don’t necessarily endorse this extreme of a narrative shift. But it did ensure that the story stayed fresh.

I liked how quickly the screenplay read, especially after yesterday’s script, which felt like I was back in Chicago walking to school after 18 inches of snowfall. Trudge. Trudge. Trudge. Stop and catch your breath. Trudge. Trudge. Trudge.

This script was more “spec-y” and respectful of the reader. Small character count. Tons of dialogue. Easy to read. The script moved FAST.

Where it ran in trouble was in how little it told us.

I barely learned anything about Lola. She used to paint. I know that. Her dad’s a meanie. I know that. But everything else was vague. Lola’s past with her mother was an important part of the story but I couldn’t tell you anything about her mom or why things went bad with her. Everything is inferred but never explained.

This is a challenge every screenwriter faces. How much do you tell the audience and how much do you keep from the audience? If you err on the wrong side of either (too much or too little) it’s the difference between a confusing mess and an on-the-nose snore-fest.

I feel like The Swells didn’t give us enough information. And information is important in a script like this because people are dying. And for readers to care about those people, they have to know those people. I mean, I still don’t know what Lola’s dad did to make her want to kill him. She mentions an old friend who may have abused her but I’m filling in the abuse part myself. That was never mentioned. I’m just guessing.

If you force your reader to guess too many times, the story becomes an unfocused blob in their heads. A series of feint images connected by cobweb-thin lines. You sort of understand what’s going on, but not enough to truly be invested.

A great example of a similar script that did this well was fellow Black List screenplay, Resurrection, about a single mother in New York City who begins seeing a mysterious older man from her past and becomes convinced he’s come back to kill her daughter. That script, too, plays with mystery and its main character losing her mind. But the difference was the writer set up the main character in a very detailed way so that we felt like we knew her.

I never felt like I understood Lola. And while we get a lot more information on Michelle, since we get to see her life back in New York, even with her I don’t know what she did for work. How she spends 8 hours of her day.

That’s something I ranted about the other week because you can’t separate a person from their job. So I always get suspicious when the writer doesn’t tell me anything about that enormous part of their life. Now that I think about it, I don’t know what Lola did for a living either.

With that said, the scene writing is good enough to keep you reading. There was always an aggressive level of dramatic irony or conflict in each scene, which meant that literally every interaction had a level of subtext to it. Either Lola’s planning to kill Michelle while they’re harmlessly chatting rowing a boat on a lake, or Michelle’s prying for info on why Lola invited her here during drinks and a card game.

It was weird because, on the whole, I never knew where the script was going, leaving me frustrated. But each individual scene had an undeniable energy to it. I never wanted to give up on the script because the scenes themselves were fun.

The Swells feels to me like a promising writer who’s still trying to figure out the weird format that is screenwriting. I don’t think you can yank people around this much without giving them some concrete pedestals to grab onto. If this was a little less smoke and mirrors, I could see it working. Right now it comes off as a foggier version of Black Swan and that movie played it as close to the line of “Is this happening or isn’t it” as you’re allowed to get.

I like the writer, though. Will definitely keep an eye out for any future material she writes.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The essence of a well-developed movie character is that there’s something deep within them that is unresolved. For those who liked this script, I’m guessing that’s what they were attracted to. Both these characters have deep unresolved issues within them. And when you have that, you have a character who’s constantly fighting themselves, which is more dramatically interesting than watching someone who has it all figured out.

You’re going to kill me but I need to push today’s Amateur Showdown review to next Friday. I’ve got too much stuff on my plate. But, in the meantime, I wanted to share this short film with you and I wanted to do so for a few reasons.

I’ve had tons of discussions over the years about what makes a good short film because if you can make a great short film, you can start your career in this industry. What’s so unique about the success of this film is that it does two things that I tell short film writers never to do.

First, keep your short under five minutes. I’m adamant about the fact that people have no time these days. Not only that, but there are so many Youtube videos available that if someone gets bored, they’re moving onto the next video FAST. I’m talking within 30 seconds. Yet here we have a short film that’s twenty minutes long.

The second thing I tell writers never to do is write “two people in a room” short films. “Two people in a room” shorts are the most common shorts out there because they’re the easiest to make. All you need is an apartment and two people. For that reason, they immediately scream out, “Amateur” and “Film School.” It’s hard to do much with two people in a room that we haven’t seen before. Yet here we have a short that has two people in a room.

The film does a THIRD thing I tell short film writers never to do which is to write a drama. It’s so hard to catch people’s interest with only characters saying things to each other. The dialogue has to be great. The actors have to be great. The margin for error is as thin as paper.

Yet here this film does all three of these things and it’s great. Why?

For starters, they’re using professional actors. I’ve seen the wife in this short in multiple recurring TV roles. This wouldn’t have worked if you were using Sara your local librarian who was in a play once in high school. If you’re going to do drama, you BETTER have professional actors or else you have no chance. I can guarantee you that.

But I think the main reason the short works is that it takes the “two people in a room” conceit and adds a little twist to by creating this whole second apartment across the street. By doing this it opens the story up beyond your typical “short that was shot for no money.” It feels bigger. It feels more like a production. And that’s the thing you have to get right in short films. It can’t look like you just shot in your 1932 Franklin Boulevard 3rd story cracks in the wall studio apartment. There needs to be some production value and you see production value all over this short.

Then, as a story, it takes some twists and turns you don’t expect. And THIS I think is essential for short films. You have to throw some curveballs at the viewer to keep them invested. It isn’t just two people crying about a car crash for twenty minutes (I literally watched a short film once where that was the plot). When you’re writing drama, it shouldn’t just be about emotions and monologues and tears and deep thoughts. You have to have some story in there and that’s why The Neighbors’ Window separates itself from all the other drama shorts. It has a story. There are several big plot developments. There is a beginning, middle, and it doesn’t all go as expected.

Curious what you guys think about this little film. I thought it was great.