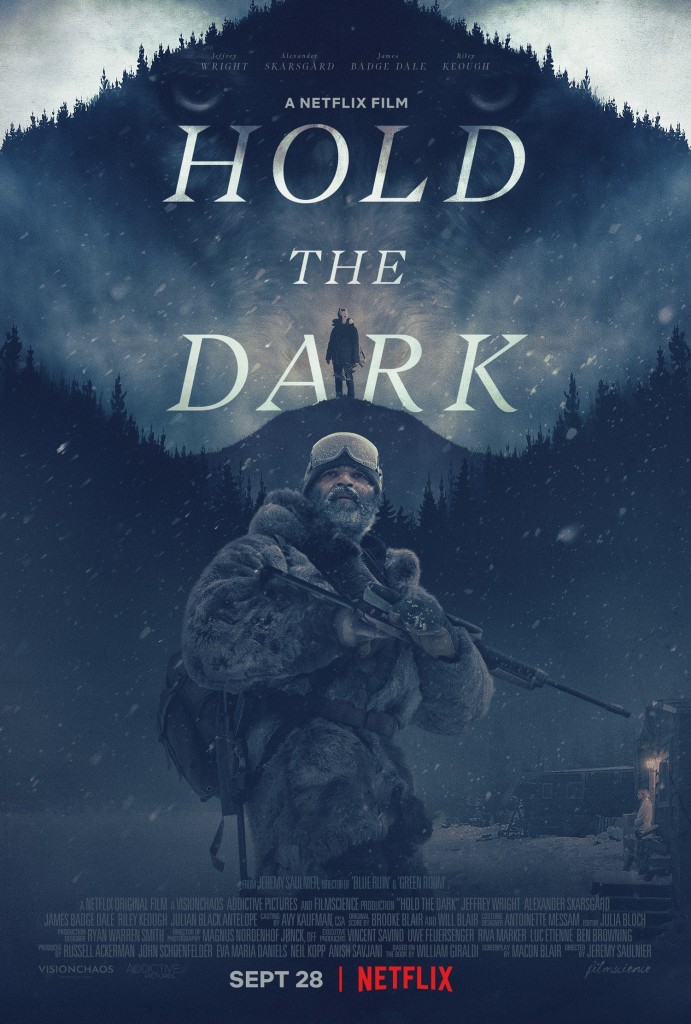

Genre: Drama

Premise: After a young child is taken and killed by a wolf, an Alaskan woman hires a wolf expert to find and terminate the offending wolf.

About: It’s the newest Netflix Original release. But don’t let that scare you off. This one is supposed to be good. It stars Big Little Lies standout, Alexander Skarsgård, and Westworld mainstay, Jeffrey Wright. It’s directed by Green Room director Jeremy Saunier and written by Macon Blair, an actor friend of Saunier’s who appeared in three of his films.

Writer: Macon Blair (based on the novel by William Giraldi)

Details: 125 minutes long

Some people consider Jeremy Saunier the best kept secret in Hollywood. His second movie, Blue Ruin, became an out-of-nowhere Rotten Tomatoes success with a 95% rating. The movie didn’t have a single known actor in it. The next film in his color-coded dualogy, Green Room, starring Anton Yelchin and Patrick Stewart, became a cult sensation, garnering similar critical praise. This adoration helped Saunier land a two-episode gig on the latest season of True Detective. And I’m sure it’s only a matter of time before Saunier gets offered a DC property, if he hasn’t already.

One of the reasons I was so eager to check Hold the Dark out was because the jury was still out for me on Saunier. I found Blue Ruin to be overly bleak. And Green Room, while interesting, was a genre mish-mash. I was never quite sure what I was watching. With that said, we need a strong new voice in the directing game. The ranks are getting stale. Not to mention, I’m excited by the fact that Netflix may have, for once, produced a good movie.

Writer, wolf-expert, and highly depressive Russell Core, flies to an isolated Alaskan town to meet a woman who claims that a wolf killed her child. She wants him to find and kill the wolf for which she’ll pay him handsomely. But Core gets the sense – along with us – that something’s off about the woman. She hasn’t even alerted her husband, who’s off fighting in Iraq, that their son is dead.

After hunting down the offending wolves (which amounts to a 5 minute walk to the nearby forest), Core gets cold feet and heads back to the mother’s house, where he learns she has fled. He heads downstairs into the basement, where he finds her dead son, rolled up in plastic. It turns out he wasn’t killed by wolves after all.

Meanwhile the boy’s father, Vernon, comes back from Iraq and is none too happy to find out his boy is dead, his wife is gone, and some big city wolf expert was staying at his place. So mad, in fact, that he shoots two local cops. The deaths are a precursor to a string of killings that include the coroner who dealt with the boy and the local witch doctor.

When the cops come asking Vernon’s best friend if he knows anything about the killings, the friend goes upstairs, rigs up a gatling gun, and starts gunning down everyone within a 2000 foot radius. Core is nearby, watching all of this go down. But if I’m being honest, I have no idea what his role in the story is at this point. Eventually they kill the friend in a dramatic shootout where he falls from his perch spread eagle in slow motion, a shot so poetic I’m convinced it’s the only reason they included the scene in the first place.

From there, we intercut between Core, the local sheriff, and Vernon, who seems to be on some side-mission to kill every friend of his. I think the rest of the movie is about Core and the sheriff looking for the missing mom, but you’d have to strap Saunier and Blair to a polygraph test to know for sure. The further on this disaster goes, the less sense it makes.

Oh man.

I’ve seen some brutally bad movies this year. But this is a special kind of bad. It’s the kind where the filmmaking and acting are so good that you can’t logically comprehend why the writing, then, is so awful.

What’s so funny to me is that 20 years ago, the big rah-rah talking point in Hollywood was, “Imagine how good movies would be if there was no studio interference. If those guys in the suits would just get their bean-counting hands away from the creative folk and let the writers do their jobs, we’d only have great movies from here til the end of time.”

Well now we’re seeing that exact scenario play out. This is how Netflix and Amazon are luring talent to the less glitzy world of streaming video. “We’ll let you do whatever you want. Not a single note.”

If you don’t have smart development people calling you on your shit, you’re going to create shit. And this script is full of shit. It’s a mish-mash of nonsense that never picks a lane. Is it a movie about revenge? Is it a murder investigation? Is it a character study? Is it a war movie? Is it a serial killer flick? Is it an action film? Is it about PTSD? Is is about a small town pushing away big city outsiders? Is it a horror flick?

Hold the Dark tries to be all of these things and becomes a giant bag of screenwriting compost in the process.

I’ll tell you exactly when I knew this script had no hope. It didn’t take long actually. In an early scene, Core is sleeping at the mother’s house. Why is he sleeping in a strange woman’s house when there’s a motel nearby? Who knows. Anyway, he wakes up in the middle of the night to see the woman, completely naked, standing in the middle of the room, wearing a mask. She then takes off the mask, slides next to him, makes him choke her for a minute, then goes to sleep.

My head fell, my eyes closed, I shook my head. This is the kind of garbage idea beginner writers pull all the time because they don’t know what drama is. They don’t know what suspense is. They don’t understand conflict. They don’t know that characters need logical motivations to dictate their actions. They don’t even know that a scene needs a plan. Why do the hard work when you can scrap together a flashy image that’ll look good for two seconds despite the fact that it has nothing to do with anything?

I was like, “Yup. Guaranteed the rest of this movie is going to be trash.” And it was. The main character keeps shifting (it’s Core, no it’s the local Sheriff, no it’s Vernon), which is fine if your name is Quentin Tarantino. Not so much if you’re Johnny First Screenplay. We’ve got classic beginner mistakes like random flashbacks thrown in at arbitrary intervals. We introduce brand new characters halfway into the script. And the plot – oh the plot. It was as if they let the location scout direct the film. They had all these places to shoot but no script to tie them together. So they said, “Let’s shoot them all and figure it out later!”

Also, the script is so steeped in bleakness that it becomes impossible for us to emotionally invest in what’s happening. Classic beginner mistake. If you only hit one emotional beat the whole time, your audience becomes numb. They need a range of emotions so they have something to compare and contrast said emotions to. There’s an old saying that you want to take your audience on an emotional roller coaster. If the same tone is hit every scene, you’re not on a roller coaster, you’re on a road.

So we’re right back where we started folks. I’m glad that Netflix is giving people jobs. I really am. It’s hard to find screenwriting money outside of television these days. But if these guys want to be taken seriously in the feature world, they need to revamp that entire department. This movie is garbage. There’s not a single thing about it that makes sense and, in large part, that’s due to the lack of oversight. And the reason I know there was no oversight is because even a first year script reader could’ve identified and helped clean up some of these mistakes.

[x] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the time

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The other day we talked about the importance of understanding the 3-Act Structure. Hold the Dark is an example of what happens when you don’t know what the 3-Act Structure is. This movie follows no outline. It has no plan. It goes wherever it wants whenever it wants. And the results of that writing style are here on display to study. Watch this. Feel the frustration. Let it inspire you to learn the proper way to tell a story.

Just a reminder that Halloween is fast approaching. That means we’ll be doing an all-horror Amateur Offerings the weekend of the 20th. Get those horror scripts prepared and have them in by October 18th!

If you haven’t played Amateur Offerings before, shame on you. A vote from you could mean the difference between a screenwriter starting his career and spending the rest of it in obscurity. So stop watching those lame Netflix C-movies over the weekend and read some damn screenplays! Afterwards, cast your vote for your favorite script in the comments section. Voting closes on Sunday night, 11:59pm Pacific Time. Winner gets a review next Friday. — If you’d like to submit your own script to compete in Amateur Offerings, send a PDF of your script to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the title, genre, logline, and why you think your script should get a shot.

Good luck everyone!

Title: Death Swap

Genre: Horror

Logline: Four friends must survive the night and each other when a cursed board game possesses their bodies with evil spirits.

Why You Should Read: Following the massive box-office success of ‘Truth or Dare’, I wanted to come up with another horror spin on a well known game. My brainstorming led me to this Jumanji meets Hellraiser mashup, where teens find a board game that swap their souls with evil voodoo spirits. It’s a pretty much contained horror that I hope has enough potential to get some feedback from the SS community. But honestly guys, I just want to get better as a writer. I am looking for brutal, honest feedback. If you think it’s a script worth pursuing, I would be grateful for any notes you can provide.

Title: The Fighting Girlfriend

Genre: WW2, Biopic

Logline: When her husband is killed by Germans in WW2, a widow propositions Stalin to be one of the first-ever female tank commanders. She becomes a symbol of hope for the Russian people as she aims to recapture her hometown, but also a target for a ruthless and elite Nazi tank commander…

Why You Should Read: It’s a WW2 version of UP but instead of a house with balloons, it’s a badass T-34 tank. We’re replacing the grumpy Carl with a 36-year-old woman hellbent on revenge whose crew is barely 18 years old and have never been in battle. She’s not heading to Paradise Falls, she’s clawing her way to Minsk, her hometown, and will partake in one of the largest (and bloodiest) tank battles of the entire war. I’ve been reading Scriptshadow since the Avatar film review and proud devotee of G.S.U. Thank you for the opportunity and I hope you enjoy.

Title: Truth or Consequences, New Mexico

Genre: True Crime/Thriller

Logline: After the arrest of David Parker Ray, one of the most sadistic men in US history, the consequences of his heinous crimes unfold through the eyes of different characters in search of countless missing victims.

Why You Should Read: I’ve been obsessed with this little-known true story ever since I read about it a year ago. Although it’s filled with shocking turns and twisted details, I wanted to focus on a theme more relevant to today: the search for truth in a world where there are as many versions of it as there are individuals. For those faint of heart, I can assure you, I didn’t want to write a cheap and gruesome horror movie, instead, this is something more human. I could’ve written this like a real-life version of Saw, but why bother turning it into a torture-porn movie when the investigation after his arrest became greater than anyone could have imagined. For anyone willing to give it a try, I would be eternally grateful and will obviously try my best to be part of any discussion.

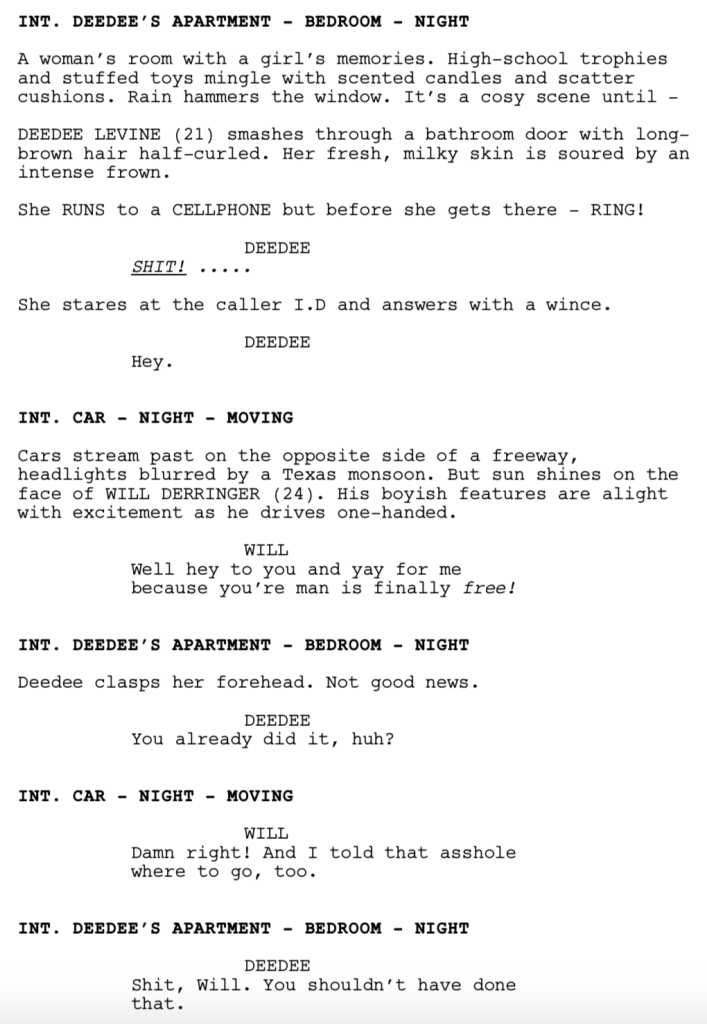

Title: Remorseless

Genre: Sci-Fi/Thriller

Logline: A PTSD-afflicted veteran joins a secret military program that promises to wipe his traumatic memories and give him a fresh start with his daughter, but discovers the only memories being erased are of the brutal missions meant to earn him his freedom.

Why You Should Read: Title, genre and logline, or I’ve not done my job… But for added support, a Black List review had this to say: “Hollywood loves a smart, sophisticated grounded sci-fi spec, and this script definitely delivers on that front. It’s easy to imagine this script making waves in the industry considering its bold concept and strong, complex leading man. Massaging the sequence of twists, as well as the way the story ends, could give it the extra shine it needs to stand out among the crowd and deservedly rise to the top.” I’d be interested in your – and the Scriptshadow community’s – take on how to help this script “rise to the top”

Title: DILATION

Genre: Thriller

Logline: A young woman terminating her pregnancy is kidnapped by a pro-life extremist with plans to terminate her once the baby is born.

Why You Should Read: This is a Nicholl semi-finalist. Since its placement, I’ve had feedback from producers/agents and refined it. It’s also had a logline consult from Carson. All this has been in preparation for the ultimate test. The scriptshadow community. — One important note. Although the antagonist is pro-life, and inspired by research into extremists, this is not a belief bashing exercise. It deals with big and divisive themes, but ultimately, it’s an imaginative thriller driven by carefully crafted characters with personal motivations. And it has a talking toy called Richard Dog. Please read and comment. I’d like to this to be all it can be.

The most tragic thing in the world is an abandoned screenplay. Okay, maybe that’s an exaggeration. But at least in the screenwriting world it’s true. There have been tens of millions of abandoned screenplays over the years. Maybe more. And the reason that’s a travesty is because we’ll never know if any of those would’ve been great movies. Jordan Peele almost quit writing Get Out fifteen times. Imagine for a moment if he would’ve given in just one of those times? He wouldn’t have an Oscar on his mantle.

So let’s talk about why writers give up on screenplays. The most common scenario is you come up with an idea you’re excited about and need to write it NOW! You rip open Final Draft, start typing away, and the pages are flying by! You get through the first act in a few days! Then, seemingly out of nowhere, everything sloooowwwws down. That magical inspiration has been replaced by a dogged hatred for film. You have no idea what happened. “Everything was so easy before!” you cry out to your dog. “What changed?”

What changed is that when we come up with ideas, we’re mainly thinking about the setup. Take Independence Day. When you come up with that idea, you’re not thinking about what the characters are discussing on page 70. You’re thinking about the alien ship hovering over the White House then blowing it up. When you finish writing those scenes, you’re left with… well, you’re left with THE REAL STORY. The stuff with the characters and the theme and the relationships. And you weren’t thinking about that. This is why most screenplays die in the early stages.

Also, a new idea can feel like the greatest movie in the world! Santa Clause kidnaps Jeff Beznos because Amazon is putting him out of business? Hell yeah, you say! I can see the opening now. Santa catches his elves ordering Christmas toys from Amazon. Except three weeks later you wake up and realize this is the dumbest idea ever and it has zero legs. Of course if became a screenplay casualty. So here’s my first piece of advice to you.

Tip #1: When you come up with an idea, sit on it for at least three months.

I know that sounds crazy. But I’d even extend it to six months if possible. Bad ideas disappear quickly. Good ideas stick around. So if you’re still thinking about an idea six months after you conceived it, chances are it’s worth exploring. Not only that. But by waiting, you can add notes and flesh out the story. I think of these notes as “script ammo.” The more script ammo you have going into a script, the more likely you are to finish that script.

Okay, let’s say you come up with an idea, you sit on the idea, six months later you still want to write the idea, in the interim you’ve come up with script ammo for your idea, so you start writing your script, onnnnn-ly to end up in the same predicament. You’ve gotten a LITTLE further than you would’ve had you started right away. But still, by page 60, your creativity has taken a vacation in the Bahamas. What’s going on? I’m going to tell you what’s going on. But it’s going to make some of you mad. So if you’re easily triggered by words that rhyme with “shoutshine,” please turn away.

Tip #2: The number 1 reason for getting stuck is that you didn’t outline.

There was a time when I thought outlining was the equivalent of throwing baby squirrels in a blender – pure evil. Since then, I’ve learned that nearly all anti-outliners are beginners or intermediates who believe that outlining destroys artistic expression. Meanwhile, 99% of professionals swear by outlining. So who do you think is right? The great thing about outlining is you’ve created a safety net for idea generation. You have a plan in place for any moment you run into trouble.

I’d always found this to be the end-all be-all solution to writer’s block. You can’t be blocked if you’ve written it all out beforehand. But a writer recently brought up a good point to me: “What if you run out of ideas in your outline?”

An outline is essentially a script, only abbreviated. Just because you’re writing in outline form doesn’t mean you magically have ideas for every stage of the story. It’s arguably harder to generate ideas in outline form because you’re not building ideas on a foundation. You’re building on conceptual fragments – “idea babies” if you will. So what happens if you can’t even finish an outline?

Tip #3: An outline is useless without a pre-existing understanding of story structure.

An outline isn’t some random sequence of ideas you cobble together. It must be built on the basic tenets of story structure. That means before you write anything down, you must understand that stories have a beginning (where you set up the main character’s journey) a middle (where that journey is put to the test) and an end (where you conclude that journey). Anti-structuralists will debate this but it’s the basis for all the best stories ever told so ignore them.

The beginning of a script (Act 1) will run you about 25 pages. The middle (Act 2) will have about 50 pages. The end (Act 3) will have about 25 pages. Why is it important to know this? Because one of the reasons we give up on screenplays is fear of a blank page we can’t fill. The less we plan, the sooner that page arrives. The goal then is to distill as many of those 100 pages into manageable chunks as possible. You don’t have to write 100 pages. You only have to write 25. And then you only have to write 50. And then you only have to write 25. Then you’re done!

But 25 is still a lot when the creative juices aren’t flowing. So let’s distill the script into even smaller chunks. I favor the 8-sequence method. Act 1 has two 12 page sequences. Act 2 has four 12 page sequences. Act 3 has two 12 page sequences. Now you don’t have to fill up 100 pages. You only have to fill up 12. Then you only have to fill up 12. Then you only have to fill up 12. You get the idea. For this approach to be effective, you have to know what to do within each of these sequences. If you bear with me, I’ll help with that.

Sequence 1 (page 1-12) is where you set up your hero’s normal everyday life and then throw a problem at them that interrupts their life. Upgrade – A guy with a nice life has it ripped apart when his girlfriend is killed by criminals and he’s paralyzed.

Sequence 2 (page 13-25) is where your hero will resist the journey before coming around and thrusting himself after the goal. There’s some leniency here. Sometimes this is a “calm before the storm” sequence where the machinations of the plot force the hero into action. Gone Girl is an example of this. After Nick finds out his wife is missing (Sequence 1), he’s dragged into the investigation whether he wants to be or not.

Sequence 3 (pages 26-38) This is where your hero will begin their pursuit of their goal. This is a very logical section. Whatever your hero is trying to get, you have them take the first steps towards getting there. In Game Night, it’s going to be leaving the house so they can find the “killer” in this game. In Jumanji, it’s traveling across the countryside to find the crystal that transports them out of the game.

Sequence 4 (pages 38-50) This is where your hero realizes things aren’t going to be easy. It’s also where you begin exploring the conflict within your relationships. This is what makes scripts fun, is that they aren’t just about physical obstacles. They’re about inter-personal obstacles (disagreements, old beef, differences in world-view, deep-seated issues characters have been avoiding for years). To use Jumanji as an example again, this is the sequence where The Rock and Kevin Hart get into a big fight about the deterioration of their friendship back in the real-world.

Sequence 5 (pages 51-62) Something significant should happen at your midpoint that throws things out of whack. Your characters are forced to react to this new challenge, which distracts them from the ultimate goal. In Juno, this is the scene where Juno comes over to Mark’s house and Vanessa isn’t home. The two spend the afternoon together, where things become dangerously close to inappropriate. It changes the entire dynamic of who Juno is leaving her child with.

Sequence 6 (pages 63-74) This is where your hero gets back on track and makes a push for the goal. However, things will end up imploding on both the plot side and the character side and your hero will end the sequence at their lowest point, so low that we’re convinced they’ve failed. In A Quiet Place (spoiler), this is where the dad dies.

Sequence 7 (pages 75-87) should see your character mope around a bit before apologizing or resolving issues with other key characters. This then reinvigorates them and they either run after the Ark or confront the villain or drive to the airport to STOP THAT PLANE.

Sequence 8 (pages 88-100) This sequence should be the easiest to write. It’s the final showdown. The big climax. Tom Cruise fights Henry Cavill to stop the nuclear bombs from exploding. Harry professes his love for Sally. Natalie Portman confronts the being inside the heart of the Shimmer in Annihilation. You’ll then have 1-3 prologue scenes and you’re done.

This is a VERY simplified breakdown of the 8-Sequence method, guys. The page numbers are not to be taken literally (some sequences may be longer, some shorter, depending on your story). You’ll want to throw a ton of obstacles at your heroes during sequences 3-6 (if your recruitment of a former girlfriend scene feels lame, throw a crazy Nazi into the mix – Raiders of the Lost Ark). I also skimmed over how important character development is. When you’re struggling to fill pages, it usually means you’re not exploring characters enough. You need characters with flaws so that you can build scenes that challenge those flaws. And you need unresolved conflict in every major relationship in the movie. That conflict will be worth 5-6 scenes in the script of just them trying to hash out their differences.

Feel free to play around with the format, especially if you’re writing scripts for practice. However, if you’re a newbie, it’s a good idea to learn how to write structured screenplays. Once you learn the rules, you’ll be more successful breaking them.

Now you understand structure which allows you to properly outline which allows you to write a script without getting stuck. All good in the hood, right? Yeah, we wish. Just because you plan ahead doesn’t mean you won’t encounter problems. You’ll often find that something you were convinced would work doesn’t. Or your main character is boring. Or you encounter a plot problem that doesn’t have a solution. I once wrote a time-travel script where I needed my main character to travel through time whenever he wanted, but all the other characters could only time-travel once. I never solved the problem and eventually gave up on the script.

If you’re still running into these blocks, here are some things you can do…

WRITE DOWN THE EXACT PROBLEM – Most writers can’t get unstuck because they haven’t identified what’s wrong. Why are you stuck? Is it because you don’t know how to get your hero from A to B? Is a scene boring and you don’t know why? (Add conflict somehow!) Do you not know what your hero should do next? (Add mini-goals!) The more specific your problem is, the easier it will be to find a solution to it. It takes me awhile to fall asleep so I like identifying problems then trying to solve them as I drift into Dreamland.

KEEP WRITING EVEN IF IT SUCKS! – Writing doesn’t cure all. But it cures more than not writing. I’ve found that if you write for long enough, you’ll eventually come up with a good idea, no matter how unlikely that seems in the moment.

BOUNCE IDEAS OFF SOMEONE ELSE – Talking out loud, even with a friend who knows nothing about screenwriting, can lead to ideas. Give them a bare-bones summary of your story, tell them why you’re stuck, then throw ideas back and forth at each other. No-Judgement Zone. Terrible ideas are fine because lots of good ideas are born out of bad ideas.

THERE’S GOLD ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THAT PROBLEM – The biggest breakthroughs in screenwriting tend to come from solving the biggest problems. Some of you may have experienced this. You thought there was no way to save your script. You spent weeks trying to fix the unfixable. Then when you finally came up with the solution, it helped you see the script with a defining clarity that, up until that point, didn’t exist. There’s something about defeating tough problems that elevates your understanding of a screenplay.

IF ALL ELSE FAILS, GET FEEDBACK – If you’re truly stuck and can afford it, get professional feedback. Most readers will read unfinished scrips for a discount. And I know with me, it helps if the writer tells me exactly what’s wrong. That way I can specifically troubleshoot the problem. If you can’t afford professional feedback, make your screenwriting friends read your script. You’d be shocked at what a new pair of eyes can see that you can’t.

Also, keep in mind that there’s a reason screenplays are rewritten so much. It takes awhile to find the best version of your story. So it’s okay if you can’t figure things out right away. Follow the 8-sequence formula, get AN ENTIRE SCREENPLAY WRITTEN, even if it’s not perfect, evaluate the script for problems, then start solving those problems. The great thing about screenwriting is that there’s always something to improve. So if you don’t know how to solve one problem, work on another. And what you’ll learn is that each solved problem generates ideas that solve other problems. If you truly believe in the screenplay, guys, don’t give up on it. Don’t be Alternate Universe Jordan Peele who didn’t win an Oscar because he gave up.

Genre: Romantic Comedy

Premise: A woman finds herself pregnant with twins from two different men, a rare real-life occurrence known as “superfecundation.”

About: Just a reminder. This is the script I talked about last week. It made the semifinals of the Nicholl, which, while admirable, rarely leads anywhere. Unless your name is Savion Einstein. Einstein would later go on to sell this script to Sony Screen Gems. Some of you might be wondering, “How come a sale-worthy script didn’t advance past the Nicholl semis?” Uh, have you guys been paying attention? Nicholl wants thematically dominated scripts that have a social or global agenda only. If you’re wondering why your otherwise well-received action or horror spec didn’t get far, you now know why.

Writer: Savion Einstein

Details: 116 pages (5/24/18 draft)

I was excited to read today’s script and I’ll tell you why.

It has a low burden of investment.

Burden of investment refers to the level of complexity in a screenplay. The more complexity you add, the more is required from the reader to keep up. A script with 8 characters has a lower burden of investment than a script with 30 characters. A script that covers a setup we know well (buddy cop comedy) has a lower burden of investment than a script that explores a 16th century war in China. A script with a clean setup, conflict, and resolution has a lower burden of investment than a script that’s told out of order.

I bring this up not to warn you away from writing scripts with a high burden of investment. Godfather 2 has a high burden of investment. That movie was pretty good. Only to remind you that unknown spec scripts are the lowest rung on the ladder, which means readers are less likely to invest in overly complicated scenarios.

Which is why a script like “Superfecundation” had a good chance, and ultimately succeeded, with readers. It’s a tried-and-true setup that’s easily understood. Readers don’t have to take copious amounts of notes to keep up. They’re not going to be mentally exhausted from trying to keep up with all the characters the writer is introducing. They can just read and enjoy.

After the high burden of investment of yesterday’s script, as well as a consultation script that had such a high burden of investment, I needed to break it up into three days just to process everything, it’s nice to read a script like this, where the read is effortless.

Ellie Kessler is 29, that awful age where you feel like you need to figure everything out NOW. Which is probably why she dumps her boyfriend, Ben, a video-gaming skateboarder who thinks pot is one of the five major food groups. Ben isn’t showing the commitment required for a woman who’s about to hit 30.

After the breakup, Ellie drowns her sorrows in a crazy drunken sexscapade with her rich ex-boyfriend from college, Owen. Ellie regrets the act (or series of acts) the next morning, leaves, and doesn’t call. Not initially at least. A month later, Ellie learns she’s pregnant with twins. And that one baby belongs to Owen while the other belongs to Ben.

Naturally, it’s hard for Ellie to break the news, particularly to Ben, who didn’t even know Ellie hooked up with Owen. And it only gets worse from there, as Ellie isn’t sure which guy she wants to be with. When the guys then use every opportunity the three are together to threaten each others’ lives, Ellie is forced to break up with both of them.

While Ellie deals with the prospect of raising twins by herself, Ben and Owen continue to bicker with one another. Except then a funny thing happens. They both realize that they like each other, start hanging out together, and eventually apologize to Ellie just in time for the birth. But being friendly is one thing. The real question is: What is everybody going to do when the babies are born?

I kinda felt like I was pregnant reading this.

Don’t your emotions sway wildly while pregnant? Sometimes I was patting my belly and cheering on this new rom-com take. Other times I was throwing up into my toilet and decrying the existence of this cliched genre.

Let’s refresh our memory. What’s the most formulaic genre in screenwriting?

If you said “the romantic comedy,” then DING-DING-DING, you win a prize. For this reason, it is imperative that rom-com writers come up with a situation that we haven’t seen before. If you do that, it will lead to a series of scenarios we haven’t before. That’s Superfecundation’s biggest accomplishment. You’ve never seen a situation quite like this.

Think about it. Ellie has a complicated choice with no easy answer. She can raise twins by herself. She can raise twins with only one of the guys, leaving the other. She can choose a guy and his baby while giving her other baby to the other guy. The more you think about it, the more you wonder what she’s gonna do. And when the script stays in that space of treating the situation truthfully, it’s at its best.

Unfortunately, as the script continues, it become less and less interested in exploring this dilemma honestly. For example, all three parties go to one of those “birthing prep” classes and, by the end of the session, both men have their shirts off and the teacher is electrically shocking them to simulate how painful pregnancy can be. It’s clumsy. It’s low-brow. But more importantly, it kills the suspension of disbelief. If the writer’s going to stop taking this situation seriously, then why would we continue to do so?

Another problem is the overly clean structure. The scenario is set up with the pinpoint precision of a game show. First Ellie tells one character they’re the father. Then she tells the other character they’re the father. Then she brings them together and explains how this process is going to work. You could feel the wheels and pulleys moving underneath the page. Remember that with any script, you want the plotting to be invisible. We didn’t have that here.

I was hoping, for example, that Ellie would lie to Ben initially. Not tell him that Owen was also the father. Then have Ben find out on his own, confront her, and then see where the bloody aftermath took things. It didn’t even need to be that plot point. I just wanted something that didn’t feel so clean and “screenwriterly.” Which I know is ironic considering I was arguing for just the opposite yesterday.

But the real killer here is the ending. And I have to get into spoilers to discuss this. You’ve been warned. As we’re moving towards the end, I got the sense that we were going in the direction where all three of them were going to end up together. And as this was happening, I was saying, out loud, “Please don’t all end up together. Please don’t all end up together. Please don’t all end up together.” And when they did, I almost threw my laptop across the room.

First of all, that’s not truthful. That would never happen in real life. It’s a total lie. And when you lie to your reader, your reader hates you. How do you know when you’re lying to your reader? When the answer is easy. If everything gets wrapped up in a bow for the hero without them having to do anything, you’re a storytelling liar. You’re always on a better track when your ending is difficult.

Imagine both suitors are equal. Then imagine Ellie picks one of them. The other gets screwed. That’s a much more difficult choice. But it’s more truthful. And it’s going to generate a lot more discussion afterwards. The choice to have them all end up together made me feel like I’d just wasted the last 90 minutes of my life. That’s how insulting it was.

Which is too bad. Because there’s some good stuff here. And the good news is, the development process isn’t over. Hopefully, someone at Sony will come to their senses and provide this script with a different ending. Or, even better, shoot several endings and let the audience decide. I have a strong feeling they’ll decide against this one.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Any solution in your story that’s easy should be treated with suspicion. It typically means you’re providing an “out” for your characters. It’s always more compelling when the characters have to make tough decisions, and those decisions have harsh consequences, even if, as was the case here, it’s the final decision of the story.

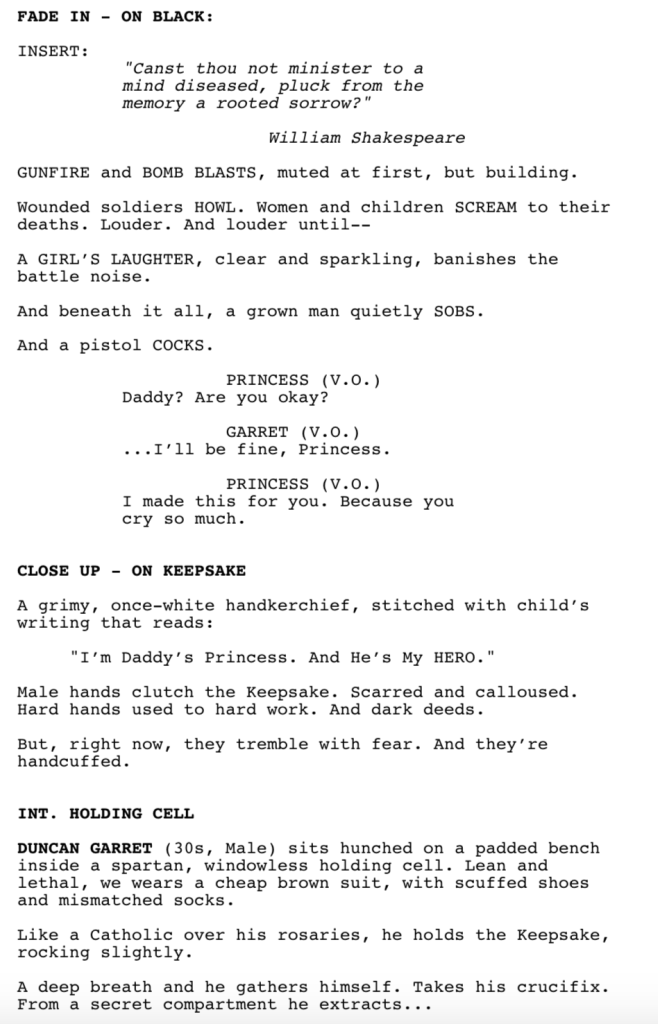

Genre: Drama/Crime

Premise: (from IMDB) When two overzealous cops get suspended from the force, they must delve into the criminal underworld to get their just due.

About: S. Craig Zahler is somewhat of a screenwriting legend. At one point he’d sold over a dozen [unproduced] screenplays. Since then, Zahler’s graduated into directing, and his newest project is the delicately titled, “Dragged Across Concrete.” Sounds like a biopic about safe spaces. Zahler will be bringing back the star of his previous film, Vince Vaughn, as well as adding Mel Gibson to the mix (who it was announced yesterday is directing a remake of The Wild Bunch). Concrete is already poured and is slated to come out later this year.

Writer: S. Craig Zahler

Details: 157 pages!

If you’re new to the site, take a look at the right panel where I’ve listed my Top 25 favorite scripts. You see number 3? That was written by this guy. S. Craig Zahler has one of the most powerful literary voices in the screenwriting community. When you’re reading a script by Zahler, you know it instantly. While that’s a big advantage in the spec world, it can be a roadblock in the “get movies made” world. Studios don’t really know how to pair up unique voices and directors. This is why most voice-y screenwriters direct their own material (Tarantino, Sophia Coppola, Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson). It took Zahler a long time to realize that. But once he did, his career trajectory shot up. He started with Bone Tomahawk, moved on to Brawl in Cell Block 99. And now he’s going to drag some poor soul across concrete. Let’s see how he did, at least on the writing end.

20-something Henry Johns has just got out of prison to find that his mother has taken up prostituting herself and using all the money to shoot heroin into her veins. Not a good look since she’s supposed to be taking care of Henry’s little brother. With no work prospects on the horizon, Henry knows that the only way he’s going to flip this situation around is by plunging back into the crime world.

Across town, cops and long-time partners Brett and Anthony are dealing with their own issues. Anthony’s thinking of proposing to his girlfriend despite suspicions that she’s not that into him. And Brett’s dealing with a wife who’s struggling with MS, and a daughter entering puberty, which has gotten the attention of all the boys in the yard, that yard being located in one of the worst neighborhoods in the city.

Things come to a head during a routine bust when Brett is videotaped roughing up a perp. The video goes viral and gets the both of them suspended for six weeks without pay. Sick and tired of his shitty life, Brett decides to do the unthinkable: Use a criminal contact to find out where the next big drug deal is going down. His plan is to come in when they least expect it, take the money, and head to greener pastures with his family. While Anthony isn’t as keen on the idea, he wants to help his friend.

So Brett and Anthony stake out the dealer’s home, and when the crew finally arrives, we notice that one of the dealers is Henry Johns. Our off-duty cops follow Henry and his crew to the exchange spot, except something is off. It turns out they’re not doing a drug deal. They’re robbing a bank. Brett thinks of calling an audible until he realizes that the payday is going to be 10x what he originally assumed.

Brett and Anthony wait for the thugs to finish the job before following them home. All parties end up at an abandoned gas station, where a wild showdown occurs. People start double-crossing each other while others are forced into temporary alliances. Despite Brett doing everything in his power to get that money, it becomes clear to us that the only person who’s going to make it out of here alive is Father Greed.

The first question you’re probably asking is, “How did you make it through 157 pages, Carson?”

It wasn’t easy.

For sometimes better and sometimes worse, Zahler likes to draw out his stories. You love it when he’s setting up rich characters with complex relationships. You hate it when he extends what should’ve been a 2-minute scene into 15 minutes of “well that could’ve been shorter.”

I mean the stakeout sequence is 10 pages long. You don’t need that. That’s not to say you can’t draw out certain scenes. But the degree to which you can stay with a scene is directly proportional to how interesting the situation is. A stakeout is boring. So of course we’re going to be bored if we sit around for 10 minutes.

On the flip side, the next scene, where they discreetly follow the criminals to their rendezvous point, felt perfect at 15 pages. Why? Because there’s an ongoing sense that they might be spotted. Because the characters we’re watching have a high-stakes goal. Because a mystery emerges about what the criminals are actually up to. Better situations can be extended out.

This was an issue I had with Brawl in Cell Block 99 as well. It was taking too long to get to the point of the movie. All the best stories (in any medium) become interesting once a problem arises. If I tell you a story about my drive through Death Valley and I never introduce a problem, you’re either going to tune me out or tell me to shut up. If I tell you a story about driving through Death Valley and then my car breaks down in the middle of nowhere on the hottest day of the year (a PROBLEM), you’re going to be captivated. Stories don’t start until there’s a problem.

The “problem” in this story, which I would argue is when Brett realizes he needs to get his family out of this neighborhood, doesn’t come up until 50 pages into the script. While I’ll never say that certain plot points need to happen by certain page numbers, every page after page 15 that you don’t introduce the central problem of your story is dramatically increasing the likelihood that the reader is going to tune out.

In my case, I knew this going in, because I know Zahler’s writing so well. That allowed me to stick with the script longer than I typically would. And once we get to the problem, the movie picks up considerably. Actually, you could make the argument that a lot of those scenes that seemed arbitrary at the time became essential anchoring points.

For example, we meet Sara, Brett’s 12 year old daughter, walking home from school in a shitty neighborhood. A few boys harass her, and we get the sense that just walking home for this girl is dangerous. It’s a good scene but all I could think was, “This is a long script. Can’t we cut this scene out?” However, later, when Brett’s wife makes the argument that things are only going to get worse for Sara if they stay in this neighborhood, us experiencing Sara’s harassment becomes critical in understanding why Brett makes the choice to steal money.

Not to mention, the climax makes all the setup feel worth it. It was a clever move by Zahler to introduce Henry Johns early, ignore him for the first half of the second act, then bring him back as a point man in the robbery. Creating complicated scenarios where we’re not sure who we’re rooting for – the good guys or the bad guys – isn’t easy to do. That legwork of setting up both Brett’s and Henry’s shitty lives – even if I was bored watching them at the time – paid off in that I wanted both of them to succeed, something I knew wasn’t going to happen, which is exactly why I was so drawn in.

Despite that being well-done, I still think Zahler’s too self-indulgent. Even five minutes in a movie is an eternity. You can get any point across in 5 minutes. But with Zahler, he’ll double that without a second thought. And while these endless scenes never derail the movie, they certainly wreak havoc on the pacing. I hear the director of The Outlaw King cut 20 minutes off his movie after the negative test screening at TIFF. I would suggest Zahler do the same. You don’t want to waste a movie with character work this strong.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The stronger the motivation, the more we’ll root for your hero. I love how we get Brett’s motivation in a single monologue. Anthony is pressing him and pressing him and pressing him on why he’s risking everything for this money. Brett finally cracks…

What I learned 2: Now some of you might say, “But Carson! Isn’t that on-the-nose dialogue!?” No! It isn’t. Don’t you guys remember last week’s dialogue article? Number 2? A character can reveal backstory (or other exposition-driven information) as long as he’s pushed into it.