Genre: Supernatural Action

Premise: When the love of his life is murdered by a group of demons, a legendary monster assassin sets out to exact revenge.

Why You Should Read: Because it’s a 90 pages micro script in the vein of “John Wick” with a supernatural twist. I poured into it my passion for the Gothic and macabre, my love of wildly imaginative action and my heart’s yearning for a magical world hidden within our own. Plus, you can play a game of spotting all the references to Edgar Allan Poe’s tales and poems…:)

Writer: Tal Gantz

Details: 90 pages

It’s a week away from the juggernaut that is Star Wars. I’m doing my best not to unleash my predictions on the film, and boy is it hard. Luckily, I have a couple of news items to distract me. One is that Taika Waititi (director of Thor: Ragnarok) is probably going to direct a Star Wars film. I think I speak for everyone – and by everyone I mean me – when I say, “YIPPPPPEEEEEEE!” and “MESSA SO HAPPY DOSEE-DAY!” and “[noise Salacious Crumb makes when he laughs].”

And then there’s this bizarre the-upside-down news that Quentin Tarantino is going to direct an R-Rated Star Trek film. I mean, what the heck is happening??? Star Trek has built its reputation on being squeaky clean. Now they’re going to turn everyone into Jules Winfield? This is most likely an indictment on how desperate poor Paramount is. Although I guess if you’re going to make desperate decisions, you could do worse than Tarantino directing an R-rated Star Trek. I’ve always wondered what Tarantino would do with sci-fi. Wish granted.

While today’s script isn’t sci-fi, it’s firmly based in the fantasy world. How bout that for a segue? Let’s check out the script that won, what infamous commenter 7 Against 7 dubbed, the “Wow Are They Bad” Offerings.

38 year-old James Milton may look like you or me. But don’t be fooled. He’s a monster. He has to be in order to do his job. You see, Milton is a monster assassin.

Badass.

After we see Milton take out a monster known as The Bloody Mummer, who can manifest weapons out of thin air just by imagining them (he mimes shooting an arrow and, voila, an arrow appears, heading straight for your heart), he heads home to the love of his life, Aisling, who surprises him with news that she’s pregnant.

The very next day, Cain, a demon, shows up, and kills Aisling AND the baby growing in her womb, right in front of Milton. Milton does a turbo-grieve before heading to the monster underworld to find out who ordered the hit on Aisling. Turns out it’s some gangster monster named Prospero.

When Prospero finds out Milton’s coming after him, he hires a relentless monster known as The Red Death. After sticking his nose in a few more places, Milton runs into Red Death, and the two have an epic showdown, which Milton comes out of on top. More like The Dead Death.

That means there’s no one left to interfere with his revenge haiku. Milton connects with two old friends, Valentine, a hopelessly romantic imp, and Azrael, a fallen angel, to get the lowdown on where to find and destroy Prospero. He learns he lives underground, in something called the Tunnels of the Dead. But when Milton engages in his final showdown, he’ll learn a devastating truth about the real reason Aisling was murdered.

Let’s start with the obvious. How awesome is the pitch, “John Wick with monsters.”

It’s so awesome I just tried to buy my ticket on Fandango.

And here’s the thing – John Wick’s one weakness – that its mythology and level of detail were lacking? Gantz addresses that weakness in Monster Assassin. Which surprised me. I wasn’t expecting something titled “Monster Assassin” to be so rich and specific.

Whenever I see a really high “high concept” I’m immediately looking for whether this is a lazy poser who came up with a cool idea yet knows nothing about the world he’s writing about or if the writer LOVES their universe so much they want to explore every little crevice of it.

Gantz falls into the latter category. The reason I can tell is because he creates this entire mythology with monsters and rules and potions and spells. I lost count of the sheer number of creatures in this. This isn’t the kind of thing you write off-the-cuff. A lot of thought went into this script. That’s a fact.

And for about 40 pages, I was all-in.

But a couple of things derailed my investment – one that wasn’t Gantz’s fault and one that was. The first issue is that I’m not into this subject matter. It’s the same reason I’m the one person who didn’t love Killing on Carnival Row. As hard as I try to give a shit about fairies, I can’t. I don’t care if an angel gets his wings back or fairy gets its dust back or a unicorn gets its golden snout back. I try. I really do. But I can’t do it.

The bigger issue, though, is that this is an achingly pedestrian investigation. It’s almost like it was plucked out of a “Noir 101” text book. You go to Place A. They tell you to check out Place B. Go to Place B. Bad Guy A shows up to battle you. You beat him but before you kill him, he tells you where Bad Guy B is. He’s at Place C. So you go to Place C. Wash, rinse, repeat. It was annoyingly simplistic and after awhile, I got bored. You put so much imagination into this universe. Why wouldn’t you use some for the investigation?

On top of this, there were too many references to other movies. The mirrors in Azrael’s place were obviously lifted from the paintings in Harry Potter. The Sanctuary, where monsters stay and can’t attack each other, was obviously taken from John Wick. We have the club scene from The Matrix. But the worst of them all was placing a hidden area at a train station. I mean, come on. I saw one Harry Potter movie ten years ago and I know that reference.

If you’re going to take the time to build this extensive mythology, you should take the extra time to build your own original scenes. You’ve put too much into this to look lazy.

My final knock against Monster Assassin is that HOLY SH#T is it expensive. How expensive?

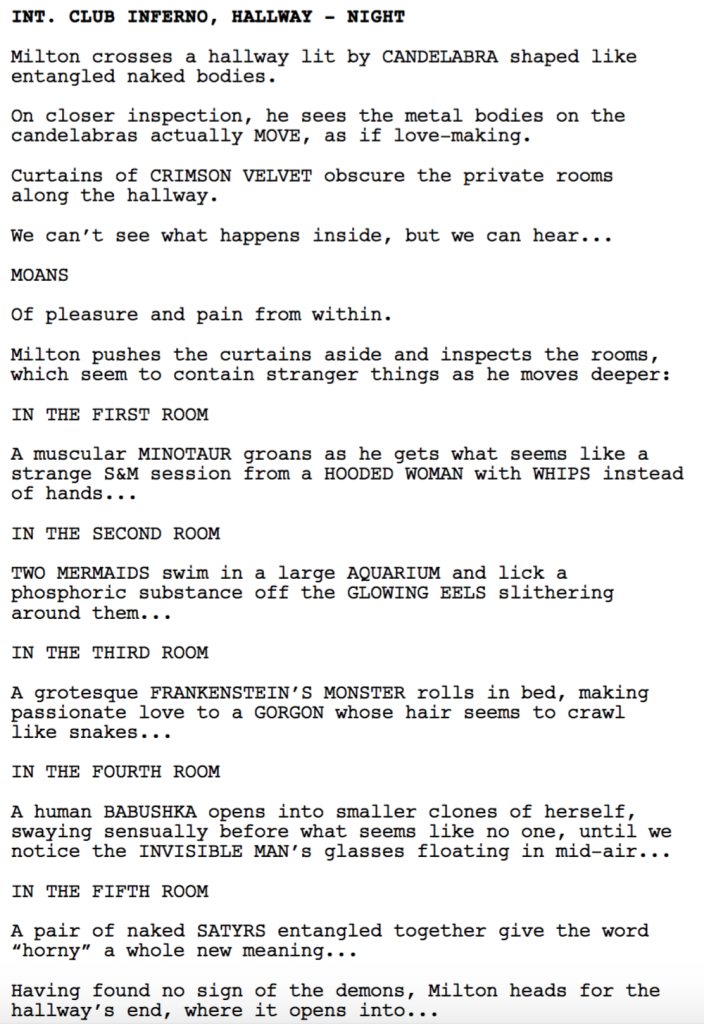

This shot alone would cost a couple of million dollars.

I don’t usually get on writers for money. A story is what it is. You can’t make a movie called Jurassic World and have the entire thing take place in a basement. People are coming to that movie to see dinosaurs. So I get that we needed monsters here. But there is “monsters” and there is a blatant disregard for financial reality.

Netflix’s upcoming “Bright” uses, arguably, bad prosthetic make-up to create its one major monster-type. AND THAT MOVIE COST 90 MILLION DOLLARS! Going off that number, Monster Assassin would cost three times that at least.

Remember that the similarly budgeted Killing on Carnival Row STILL hasn’t been made and that script has “the best unproduced script in Hollywood” tag going for it.

I hate limiting imagination but the rule here is one that plays across the board in moviemaking. Ask yourself, “Do I really need this shot/scene/character/set-piece?” If the answer is a definite yes, include it, regardless of how much it costs. If not, look for a cheaper way to do it. And remember that cheaper usually forces you to be more creative and come up with a better option.

But yeah, the last thing you want is producers doing a spit take as they read your 40 million dollar version of Hulk vs. Iron Man on page 17. You have to show that you somewhat understand the financial limitations of the business.

That wasn’t the biggest problem though. That was more of a teachable moment. My big problem with this script is the snore-worthy investigation. Do more with that. Be unexpected. Be brave. Try out new things. You can’t use a 50 year old plot template on a movie called Monster Assassin. You gotta be more creative.

Script link: Monster Assassin

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s a neat moment in this script where Milton gets into a fight with someone next to an exotic fish tank. The tank crashes, Milton grabs an eel off the floor, stuffs it in the other guy’s face, and it electrocutes him. — I find that moments like this work best WHEN YOU’VE SET UP THE EEL AHEAD OF TIME. You show the character walk in to the location, you establish the eel in the tank. The owner gives you some history on the plight of the eel. We see the eel use its electricity to stun a fish. Then, ten minutes later, when the fight happens, the tank breaks, and the eel is pulled into the battle, it plays WAAAAY better because we’ve spent so much time setting the eel up. — In Monster Assassin, the time between when we learn about the eel and when it’s used as a weapon is 5 seconds. So it doesn’t have enough time to create an impact.

I was going through the Talkback of last weekend’s Amateur Offerings, and I came upon this comment which unabashedly ripped into the entries. I don’t necessarily like comments like this. I prefer feedback to be more constructive. But if I sense a raw truth to the comment, like the commenter really feels this way and isn’t just trying to stir shit up, I think that’s worth discussing. The truth is, some of the things 7 Against 7 says here, are true. And maybe by talking through them in a calmer more productive fashion, I can help some of you improve the types of ideas you come up with and the scripts you write. So I’m going to go through 7 Against 7’s entire comment, piece by piece, and give you my thoughts along the way. Some of this might be hard to hear. Prepare to be triggered. But hopefully, we’ll all be better writers in the end.

I’ve often wondered why writers couldn’t make a career out of selling spec scripts. These amateur offerings have shown me why.

If a production company had 50 million dollars to spare and wanted to spawn a successful film and possible franchise, these offerings would make them cringe. I imagine these offerings are akin to what’s circulating around Hollywood, and wow, are they bad.

7 Against 7 makes a great point here that writers often forget. If someone has 50 million dollars to spend, and every line of Hollywood box office data suggests that buying a pre-existing property is a better investment than buying an original spec script, why the hell would they buy your spec script? You need to imagine you’re in a room with a big time Hollywood executive and he’s asked you that exact question. Why your script? You better have an answer. The only three answers I know of that hold weight are… 1) You’ve come up with a kick-ass concept that everyone agrees is good. 2) You’ve hit on a current trend, finding an angle just unique enough to separate your script from the pack. 3) You’re an awesome fucking writer who can execute any story, no matter how mundane it sounds. Sadly, if you’re a nobody, people might not even read your script to find out if you’re 3. Logan Martin told me that before Meat landed on Scriptshadow, only 1 guy on Reddit would read his script because the logline wasn’t anything special. So it’s best, even if you are a great writer, to nail number 1 or 2. Increase your reads. Increase your odds.

1) Title: Plummet

Genre: Horror/Thriller/True Story

Logline: Lured by a sadistic killer, a young woman fights for survival in Central Park during the dead of winter. Based on true events.

Based on true events doesn’t negate the fact that it’s the same often retreaded story of a woman being stalked by most likely a male killer.

In this age of Hollywood revelations about stalkers and rapist terrorizing women at work, home and in hotel rooms; this story will motivate no one to go to a theater. Especially not with it taking place in Central Park, NY where there has been many women raped while jogging and walking. Why even write something like this?

“Because this is a contained thriller that really happened about a real serial killer you’ve never heard of?”

I want escapism when viewing movies, not a bludgeoning from reality.

All the complaints about “lack of originality” that ring out from writers whenever Landis makes a sale; yet every week the amateur offerings on this site are terribly unoriginal and uninspiring.

You say “Plummet,” terrible title by the way, is about a woman being stalked by a serial killer. I say it’s just another crumby slasher pick. And I’d rather watch the original “Texas Chainsaw Massacre” or “Friday the 13th” or “Halloween,” or “Sleepaway Camp,” or “Black Christmas” or “Fear,” or “Scream,” or “P2,” etc.

If you’re writing contained thrillers why not tweak the genre like “Get Out,” and “Split” did? If you had an idea like one of the aforementioned, it would be easier to sale; because it’s what producers, managers and agents are looking for right now.

I’m not sure I agree with everything 7 Against 7 is saying here. There is an audience for this kind of movie. There’s something primal about survival and overcoming evil that will never go away in cinema. And something as simple as seeing the girl get away from the killer can be exhilarating. But I agree that the specific concept shaping this getaway isn’t that original. And I like the movies he’s suggesting you look to instead. Get Out and Split. Be a little more creative. A girl running around a park… I suppose that could be okay if it’s executed realllllly well. But the ho-hum setting mentioned in the premise implies that the decisions being made in the script will also be ho-hum. I can’t know for sure. But that’s where my mind goes after reading a logline like this.

By the way, I agree with him about Max Landis. Guys – NEVER use Max Landis or anything he sells as a reason for why your like-minded script should sell. Max Landis is an enigma. There’s never been anyone like him. He posts insane videos on Youtube that go viral. He has a following. He openly trashes major blockbusters then gets hired by the studios that released those blockbusters. He wrote scripts for something like 10 years before he sold anything. There are too many factors going into his success that you can’t quantify or replicate. Don’t worry about Max Landis. Worry about becoming the best writer you can be.

2) Title: MONSTER ASSASSIN

Genre: Supernatural Action

Logline: When the love of his life is murdered by a group of demons, a legendary monster assassin sets out to exact revenge.

There are no stakes, and I can’t figure out who the main character supposed to be exacting revenge against. Some random group of demons? Who is their leader and did they do this for a specific reason? If so, that needs to be mentioned in the logline; otherwise it seems like this will be a pastiche of action scenes with no clear goal and tons of flashbacks divulging backstory. Typical amateur stuff.

Also, demons and angel as warriors has yet to translate well into boxoffice success, religious people don’t like seeing their religion displayed in such a manner. And none religious people think of angels and demon combat as being silly.

“Constantine,” “Dogma,” “Legion” “Ghost Rider,” and “End of Days” all flopped.

I don’t see how any producer or production company could get excited about an idea like yours; which would be better compared to “Constantine” than any of the aforementioned. And that failed as a movie and tv show.

“I poured into it my passion for the Gothic and macabre, my love of wildly imaginative action and my heart’s yearning for a magical world hidden within our own.”

Cool, but what about stakes? Conflict? Conflict resolution? Irony? An antagonist with an coherent goal? Urgency? Set ups and payoffs?

This feels unnaturally harsh, like me reviewing a Rian Johnson film, even though I still don’t understand why the Cinephile community gave this guy a pass for using Photoshop 6 to digitally alter his actor’s faces in Looper. I can only imagine what weirdness he’s going to employ in The Last Jedi. But I digress. 7 Against 7 is right that the logline here is a bit general. I like specificity in loglines because it’s what identifies your script as unique. Still, I understood the problem and goal just fine. Kill the demons. And something about this feels more fun than the failed movies 7 Against 7 listed. “Fun” means a broader audience. Not sure what he means about no conflict. What’s more conflict-filled than taking on demons?

3) Title: Righteous Anger

Genre: Thriller/Drama

Logline: A 17-year-old Syrian refugee becomes entwined in a dangerous world of deceit and human trafficking in his Atlanta community.

Hey kids; let’s skip that live action version of the Lion King and go see this rousing movie about a Syrian refuge and women forced to be sex slaves…it’s in 3d!

Why would I pay to be shown fictional misery, when I can walk down the street and see it in reality? Movies about human trafficking have a terrible track record of not only being snubbed by the Globes and Oscars, but poor box office returns. Which production company would dip into their hard earned coffers to fund this knowing it will neither win awards or be boxoffice hit?

I have to admit I snickered at the idea of choosing between Lion King and a Syrian refugee movie. And 7 Against 7’s sentiment is correct here. This sounds really fucking depressing. However, we have to remember that not every script is vying for a 4000 theater release. If you want to make a more serious movie, you just have to make it cheap. With that said, you have to understand that these types of “heavy subject matter” scripts don’t do well on the spec market unless they’re tapping into an existing hot button topic. Almost everyone who writes this kind of stuff has to raise the money and shoot it themselves. On top of that, Righteous Anger’s logline trails off into obscurity instead of telling us what the script is about. It would be like, if I was writing the Raiders logline, I wrote, “An archeologist who searches the world for rare artifacts goes off and encounters a wild adventure…” You have to give us a more definitive goal, not summarize the general “feeling” of your script.

4) Title: Two-Time

Genre: Crime Drama

Logline: After allegations of game fixing derail his career, an ex-college football star is recruited by a disgraced university booster to steal the three National Championship trophies they helped win.

Why is it called “Two-Time,” if there are three titles being sought-after?

There are no stakes. What happens if they don’t get the trophies back? Nothing, I presume. So they’re willing to be arrested, and have their reputations further ruined, just to get trophies that have no true value?

This idea makes no sense.

Seven Against Seven is right on this one. It’s a script that I resisted posting for a long time for the very reasons he brings up. The story doesn’t make sense. What if he doesn’t get the trophies back? Nothing. He’s in the exact same spot as before. That’s stakes guys. If your character ends up in the same place whether he succeeds or fails, that means there are no stakes. Not to mention, what’s the point of getting these trophies back? You can’t make money off trophies. The only thing they’re good for is displaying. And you can’t do that since it would prove that you stole them back. The more you dig into this idea, the less it makes sense. But at least there’s a story with a goal. And that’s more than a lot of entries offered. So I gave the script a shot.

5) Title: …’Scape The Lightning Bolt!

Genre: Dark Comedy

Logline: Henry has the purest intentions. All he wants is to see his sister happy, but when he accidentally sets her up with a violent psychopath with a peculiar motto (‘Scape the Lightning Bolt)… his life takes an unexpected turn for the worse.

Did you write an entire screenplay around a phrase?

Bazinga! the movie.

What is the main character’s goal? Weather the storm? Kill the psychopath? Couldn’t he just tell her the guy’s a crazy person, show her some footage, and be done with it? I mean, the psychopath isn’t married to his sister.

Now if the guy found out that his sister’s longtime husband was a psychopath that would be more interesting. There would be more attachment and a harder goal of breaking them up. But, as is, your logline is weak and confusing.

Harsh critique but he’s right. Producers would pick this up and think the same thing 7 Against 7 did. The screenplay is about a phrase? How did that end up for Waboom Guy on The Bachelorette? The bigger problem, however, is that you’ve built a movie around the phrase, then don’t tell us what the phrase means. At the very least you’ve got to give us that. But I’ll tell you why I picked this anyway. It sounded different. And sometimes, that’s enough. Readers see so much of the same day in and day out, that something unique will catch their eye. So even with the concept’s limitations, I thought, “Why not?”

Reeves man, stop wasting your time and effort reviewing amateur offerings that aren’t market ready, or saleable. You’re not doing yourself any favors. Find another “Disciple Program,” and get yourself some production credits or something. ‘Cuz this crop of script here, are disheartening.

Just last month Amateur Offerings led to the beginning of a writer’s career. And I’d say we’re consistently finding better material on Amateur Offerings than at any other time. It’s still the best place on the net to discover new talent, in my humble opinion. :)

7 Against 7 is also forgetting something – the power of execution. If a writer has a strong sense of craft or a really unique voice, you can’t always see that in logline form. Also, there’s a bit of a secret involved in logline creation that’s never talked about. When you become a professional, you no longer have to write loglines. The funny thing is that it usually takes the same amount of time to get good at writing loglines as it does to get good at writing screenplays. So by the time we finally have a writer who can write a good logline, they no longer need to. Which is why all the loglines we see in the amateur world are, for the most part, flawed. It’s because they’re not ready yet. They’re still learning.

I think what 7 Against 7 is really railing against here are the ideas. They’re not exciting enough. They’re not the kind of idea where you go, “Oh my god, I have to read that.” Granted, that’s not easy to do. But that should be what you’re aiming for. Also, it’s a hell of a lot easier to write a good logline when you have a good idea. You do that by coming up with a fresh concept that we haven’t quite seen before. Add an interesting main character who encounters a compelling problem. This leads to the primary goal that will drive the story. Then just throw a lot of shit at them to make it hard. There ya go. Now let’s see some kick-ass Amateur Offerings entries!

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. I highly recommend not writing a script unless it gets a 7 or above. All logline consultations come with an 8 hour turnaround. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Genre: Period

Premise: A priest is brought in to be the puppet Bishop for the Emperor of Rome. But when he sees the suffering that the Roman people are going through, he dares to disrupt the status quo.

About: Leo Sardarian used to work in casting and broke onto the scene in 2013 with this script, which made the Black List. He just sold another script yesterday, that one about a rookie female marine who gets stranded on a hostile planet during earth’s attempt at colonization. Is it even possible to sell a script with a male lead anymore?? Inquiring minds want to know.

Writer: Leo Sardarian

Details: 112 pages

Yesterday’s kick-ass script got me all riled up for some period piece action, baby! This time, however, it’s back in the time machine 1600 years to Rome! Rome’s always good for some spicy conflict and sassy drama. They practically invented entertainment (killing people for sport? uhhh, geeee-nius). Also, it’s been a while since we’ve had a Roman swords and sandals pic. So you know one is coming soon. It’s either going to be Nicholas or it’s going to be something one of you guys write. Let’s check out your competition.

A note before I start. I’m probably going to get some things wrong here. This script attempts to cover so much ground that you spend the majority of your reading time trying to keep up.

We’re in Rome in the 3rd century. We’re quickly told, via voice over, that Rome is in a state of flux. Things aren’t going well. One of the biggest problems is religion, specifically Christianity. Diocletian, the Emperor of Rome, hates the religion, and routinely plucks Christians out to be sacrificed in the gladiator ring.

But Christianity is growing, and more and more people are standing up to Diocletian’s harassment. So Diocletian hires some nobody Christian named Nicholas and appoints him to be the Bishop of Rome. The plan is to make Nicholas a puppet, have him calm down the Christians whenever they get out of line.

But Nicholas isn’t as passive as Diocletian assumed. In one of the Gladiator matches where some Christian thieves are being slaughtered for sport, Nicholas leaps into the ring and reveals himself to be a seasoned warrior, killing all of the Gladiators easily. This surprise only makes Diocletian more wary of Nicholas.

So one night while Nicholas is out, Diocletian sends a group of orphans Nicholas has been taking care of to Crete, where they’ll be sold into slavery. Nicholas goes after them and Diocletian celebrates the victory of no longer having to deal with this disruption.

However, Rome continues to clash from within, and it feels like only a matter of time before the Christians rise up. An unexpected Nicholas team-up with one of the most famous figures in Roman history, Constantine, fortifies an army that actually has a shot against Diocletian. Rome. Get ready.

I’ll give Sardarian this. He’s done his homework. This is one of the best-researched scripts about Rome I’ve ever read. Every single page is dripping with detail about the famous city.

But it was far from an easy read. In fact, Nicholas was one of those reads where you looked up expecting to be on page 60, only to learn you were on page 15.

Not all stories need to be fast. But if you’re writing something this complex, something that requires tons of exposition and dudes in rooms talking, you need a plan counteract the pace.

Overwriting was a key problem. The script would often lose itself in its desire to write the perfect line. “He divests his breast plate and stakes his sword into the mud. His blue eyes gaze west — where the lands beyond the mountains are awash in golden sun-rays… The sublime beauty slightly breaching the darkness that’s clouded his eyes.” That was par for the course. Lines like “Moonlight BEAMS through the oculus of the coffered rotunda…” were common.

The reason this is a problem is because the writer is trying to impress rather than convey. As readers, all we want is to understand what we’re seeing, understand what’s happening. And if we have to read every fourth sentence twice because the writer was trying to win the Pulitzer with it, it’s very easy to lose patience. And loss of patience is the final step before boredom.

Overwriting is a common beginner mistake and should be avoided if possible. No, we don’t want our stories told in cave man vocabulary. But over-vocabularizing is just as odious…err… I mean bad.

This wasn’t the biggest problem with Nicholas, however. The main problem is that the script is trying to do too much. One of the first screenwriting tips that really resonated with me was: ZOOM IN.

Tell a SPECIFIC STORY. Don’t try to cover too much ground. For example, if you want to cover terrorism, write Die Hard. Don’t write about the five biggest terrorist countries in the world, jumping back and forth between each one, introducing us to dozens of characters and a similar amount of plotlines.

I know what you’re going to say. “Tell a serious story about terrorism with a movie like Die Hard? You crazy Carson??” I’m not talking about the tone. I’m saying it’s much easier to explore terrorism through the tight lens of a single terrorist than it is trying to cover five terrorists. You use specifics to make a bigger statement about the world.

Can that intricately woven five terrorist movie be written? It can. But only the best screenwriters in the world – those who have seen every kind of story and understand what they need to do to counteract and rein in that that narrative will be able to pull it off. And even then, it will be a writing nightmare. There will be a bigger chance that they fail than succeed.

And that’s because movies were meant for tight narratives. If your idea doesn’t fit into a tight narrative, go write a TV show or a novel. Those mediums are built for that stuff.

There was this moment in “Nicholas” where the title character sails into Rome and Sardarian details the elaborate harbor of this ancient city. Capable of docking 1200 ships. Half the ships are out of business because times are so tough. So there are criminals and barterers. It’s its own little crazy city.

And I thought: THIS IS A MOVIE! This here! I’ve never seen a film about Rome’s harbor before. That’s how you ZOOM IN. But therein lies the problem with “Nicholas” as a script. There are so many lovely details like this that get lost due to its novelesque narrative.

As much as I tried to stay invested in Nicholas, the story was too sprawling, too unfocused, and too overwritten, to keep me around. It’s a script that tests your patience. Which is unfortunate, because there are obviously many stories within this setting worth being told.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “The endless montage.” Guys, don’t write long montages. What you’re trying to do with a screenplay is DRAMATIZE EVENTS. That’s why we tune in! To be entertained by your dramatization. A montage is a list. ANYBODY CAN MAKE A LIST. Lists are the OPPOSITE of dramatization. I advise never using them outside of comedies. But if you are going to use them, keep them short. There’s a montage in this script with, like, 20 events. That’s a huge no-no.

**Alert to all major Hollywood studios – Your next war movie is here!**

Genre: War

Premise: A reluctant Sergeant in World War 2 must guide a ragtag group of soldiers to a small French town, encountering all of war’s glorious randomness along the way.

About: Man, I can’t find ANYTHING on this project. It seems to have fallen through the cracks. The script is written by Terminator 2 co-writer, William Wisher. I only read it because I was looking through my script folder and saw, “Wisher” in the file title. I said, “Hmm, I wonder if that’s William Wisher.” I then assumed it couldn’t possibly be any good or else I would’ve heard about it. I turned out to be way wrong on that one. This script is awesome.

Writer: William Wisher

Details: 114 pages

Over Thanksgiving, I took a break from the kitchen to catch some football, only to end up stumbling upon Terminator 2. As many of you know, Terminator 2 is the most impossible movie to accidentally stumble upon and not watch the whole thing. So while I kept saying I was going to watch “one more scene,” I ended up watching the entire film.

Most everyone gives the credit of that film to James Cameron. And why wouldn’t they? He’s James Cameron. However, there was always that other credit on the poster – William Wisher. Who was this guy? How come I knew nothing about him other than hearing his name associated with this movie? I figured he must be one of those lucky dopes who caught the coattails of a famous director in rare form and whose contributions to the screenplay were limited to slugline maintenance and character re-naming.

Boy was I wrong. “Combat” proves that not only is William Wisher a good writer, but that the Hollywood establishment missed one. This movie should’ve been made. And the powers that be still have the ability to right that wrong.

When we meet Private Charles Saunders, he’s in one of those gutted soldier-boat things they use to storm beaches. Which, coincidentally, happens to be exactly what they’re doing. They’re prepping to storm Omaha Beach, and when they get there, all fucking hell breaks loose. Everyone else on Saunders’s boat is killed. But he somehow survives.

Once he’s able to find cover, he’s told by a superior that he’s been upgraded to Sergeant, something Saunders is none too happy about since he has no idea what he’s doing. Before he can even find a gun, he’s got his first order: Find some other stragglers who’ve lost their platoons and cobble together a Survivors Team.

Saunders does as told, accumulating a handful of dudes you wouldn’t trust in your living room, much less trust your life to. There’s Littlejohn, a cook who barely knows how to operate a gun. There’s Cajun, an engineer from New Orleans. There’s Nelson, an intelligent guy cursed by cowardice. And a few others.

Saunders is given orders to head to a small town in France which they’ll be turning into a makeshift hospital for a battle to take place nearby. Their job is to secure the town and start preparing it. It seems like a relatively simple order. They get to travel outside the war zone and aren’t predicted to encounter any fighting. Of course, nothing goes according to plan in war.

The Germans are throwing everything at the Allies, including children and old men, who are fighting with a desperation that makes them scarier than even Germany’s best-trained soldiers. The Communists are also rolling in, and are said to be leaving a trail of destruction of their own. Let’s not forget the French Resistance, a rag-tag group of soldiers who are so filled with rage, they’re determined that everyone suffer their wrath. And finally, watch out for exploding cows. We’ve got those too. Nobody is safe during war, as all the glories and horrors of combat will be highlighted in one giant smörgåsbord of chaos.

If I haven’t been clear enough, I loved this script. Here’s why.

I was talking to a writer recently who’s writing a war movie of his own and having trouble with the soldiers’ dialogue. You see, when you write soldier dialogue, the temptation is to write a bunch of tough-guy-speak where all that matters is crude jokes and machismo. However, that’s not how the real world works. Not completely, anyway.

People speak because they want something. They speak to persuade others. They speak to try and impress someone. They speak because they’re nervous and want to fill in the silence. Take the one of the most common character archetypes. The Jokester. The Jokester’s not railing off jokes because this is a movie and it’s his character’s job to “be the funny one.” He’s doing it because he wants people to like him. The laughs validate him, make him feel good about himself. That’s why he jokes. The lesson being, as long as there’s a reason to speak, your dialogue will feel natural. And that’s the feeling I got here. There was none of this “try-hard” forced tough-guy dialogue. The soldiers all spoke like genuine human beings.

There are also a lot of powerful moments in the script – stuff that gave you insight into characters that the average writer wouldn’t have even thought about. One of my favorite moments is when Saunders tells his superior, Hanley, “I’m not cut out to be a Sergeant. I don’t even know what I’m doing.” Saunders’ flaw is that he doesn’t believe in himself. Hanley calmly guides Saunders’ attention to his team. “Do you think he should be in charge?” He points to the young scared kid. “No.” “What about him?” He points to the crazy guy. “No.” “What about him?” He points to the scatterbrain. “Well, no.” And Saunders finally comes to the realization that… wow, he’s right. I am the best man for the job.

I bring this scene up because most writers don’t go through the trouble of exploring a feeling. They have the character continue to say shit like, “I’m no good at this,” in subtle variations throughout the movie. By creating this moment that highlights the problem and attacks it head-on, it becomes concrete as opposed to abstract.

But that was just the little stuff. Combat has these brilliant sequences that highlight the randomness of war. I’m going to get into spoilers here and since I’m going to link to the script at the end of the review, I suggest you read it before you read this.

There’s this sequence where the soldiers, who are tired and hungry, walking through the countryside, come upon a… COW. The cow is just standing there like cows do. And the group tries to decide whether they should kill the thing and eat it, since they’re so damn hungry.

All of a sudden, the cow fucking EXPLODES! And they realize they’re in the middle of a mine field. At this moment, a German plane starts flying around and dropping bombs on them. They have to avoid the bombs while also not stepping on any mines. THAT’S A FUCKING SET PIECE!

This leads to a scene where they come upon a French house, see that the parents and the daughter have been gutted and hanged, discover a surviving 17 year old girl (the other daughter) hiding in the barn. She explains that the Communists – who, according to her, are far worse than the Germans – did this. The soldiers are devastated for the young girl. They then have her guide them to the town they’re looking for. But on the way, they’re attacked by Germans, who are in turn attacked by the French Resistance, who help the Americans defeat the German contingent.

The French Resistance leader, a woman, then comes over and casually shoots the 17 year-old girl in the head! The Americans all stare at her, gobsmacked. The leader explains that the girl’s family sold secrets to the Germans resulting in dozens of Jews being sent to concentration camps, all for money and land.

Take a moment and think about how complex this moment is. We saw this girl’s family not just murdered, but tortured and gutted. We feel terrible for this girl and want to do anything for her. Now, however, we’re wondering if she led us into a trap. Then this French woman kills her in cold blood. She tells us her family sold secrets to the Germans for money. But the girl was still 17. I doubt she was involved in any of those decisions. Does she deserve to be killed? And how do we even know this French woman is telling the truth??

That moment is what made the script for me. It siphoned all of the craziness into one moment that proved just how complex war is.

I mean, wow.

I know what some people are going to say. There’s some crossover here with Saving Private Ryan. In fact, that’s the only explanation I can think of for why this wasn’t made. That the script came out at around the same time as Saving Private Ryan’s (I don’t know if that’s true since the script’s undated). But here’s the thing. This script is a lot better than Saving Private Ryan from the 20 minute mark on. And a director with a unique vision could easily differentiate the film.

I want to see this movie. Who’s going to claim it?

Script link: Combat

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Combat” taught me that you can make subject matter the concept. It’s risky. Because “subject matter” is general and I typically encourage specificity in concept-creation. But that’s literally what Wisher does. He built a story around the subject matter of “combat.” The challenges of it, the unpredictability, the randomness, the fear involved. There isn’t a huge plot here. It’s about combat during war.

Genre: Dramedy

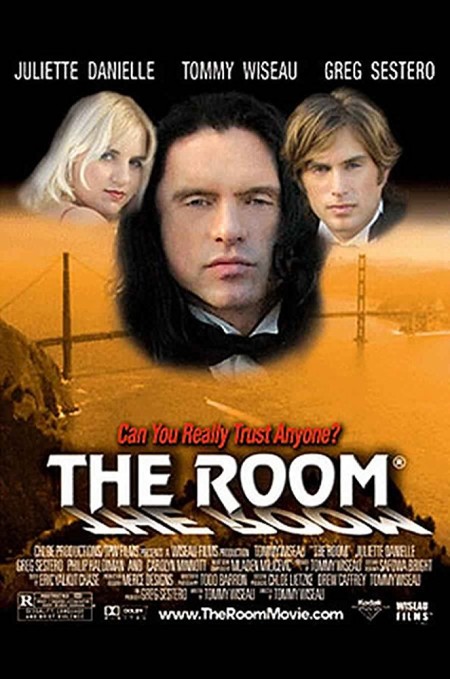

Premise: Based on the true story. The Disaster Artist chronicles the making of the worst movie of all time… The Room.

About: Been looking forward to this one for a long time! Franco’s getting the best reviews of his career (95% on Rotten Tomatoes). Franco directed and acted in the film, along with his brother, Dave Franco, his buddy Seth Rogen, Alison Brie, and Josh Hutcherson.

Writers: Scott Neustadter & Michael H. Weber (based on the book The Disaster Artist by Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell)

Details: 105 minutes

Hollywood’s got it all wrong.

They’ve concocted this ludicrously complex formula for making money, which includes coming up with a film idea that can be expanded into multiple product lines such as toys, music, and theme parks, when all along it was Tommy Wiseau who had the real vision.

Here’s his formula. Take note:

Overpay to make a movie so bad, barely anyone shows up for it, but just enough people to tell other people that it was the worst movie ever, which in turn drives their curiosity and gets them into the theater, who in turn bring their friends to show them how bad the movie is, a process that gradually builds and turns the film into a cult classic.

After six years of this, have one of the stars of the film, and the director’s supposed best friend, write a book that throws the filmmaker under the bus to such a degree and in such entertaining fashion, that the book itself becomes a best seller. Then wait for a Hollywood star to read said book, fall in love with it, buy the rights, then make a movie about the book about the making of the movie, finally bringing the story of the film to the masses, who now have no choice but to go rent the original film that this film was based on, turning said terrible film into a financial success.

That, my friends, is how you do it.

The Disaster Artist (here’s my old review of the book) is one of the most complex pieces of entertainment I’ve ever encountered. There are so many stories within stories here, so much inside baseball, all packed onto a story whose structural oddities make it a screenwriting nightmare, that there’s virtually no way to make it work. A recent test screening showed that the average audience member didn’t even know this was based on a real story. They just thought it was another wacky James Franco Seth Rogen comedy.

The Room was a movie made by an eccentric weirdo named Tommy Wiseau, a secretive wannabe actor who believed people would buy him as the next great American movie star. He befriended a shy 19 year old actor, Greg Sistero, who had Brad Pitt looks but Rob Schneider talent. The movie they made was so bad, it became a cult hit that many dubbed “the worst movie ever made.” This film is about the friendship between Greg and Tommy while making that movie.

Let’s be clear here. Franco deserves all the acclaim for this film. He wears all the hats. But screenwriters Scott Neustadter and Michael Weber aren’t far behind. They did some amazing things with this. Give Franco credit. He could’ve hired some Rogen-Franco inner-circle assistants to write this film. But they spent the money to get it right.

How tricky was the script?

For starters, it takes place over a number of years. Movies work best with tight time frames (2 weeks or less is ideal). The main exception to this rule is period pieces (by that I mean hundreds of years ago, not the 90s). The reason long time-frames are bad is because it’s harder to sustain tension in a story if you’re always stopping and starting. An 8 month time jump is a momentum killer. I’m not saying it can’t be done. But trust me, it’s a huge challenge to make jumps like that seamless. And these guys did it.

Then there’s the movie-within-the-movie aspect, always a challenge to pull off because you’re figuring out how to divide time between the “real life” stuff and the making of the movie. Also, movies about Hollywood are always terrible. So you’re diving into those shark-infested waters.

The biggest challenge, however, is the tone. I can only imagine what the meetings were like discussing this. People who love The Room are coming into this film hoping for a lot of that goofy “so bad it’s good” comedy. However, The Disaster Artist can’t be that movie. It’s not The Room. So how do you appease those expectations? On the other side you have people who’ve never seen The Room. They’ll make up the majority of the audience. What movie are you giving them? Because it has to be a different movie than the one you’re giving Room lovers.

How did Neustadter and Weber solve this problem?

The answer is why these guys are making 7 figures a job and you’re not.

They anchored everything in the friendship between Tommy and Greg.

Here’s why that matters. This movie can’t possibly appease everyone. But the thing that EVERY audience member relates to is friendship. The struggles and complications of friendship are universal. This is why I tell you guys that while the plot is important, you gotta get the relationships right. That’s what’s going to hold your story together.

But this was one of the most complicated friendships I’ve ever seen. You have Tommy, who’s so socially unaware that he clings to anyone who gives him even a modicum of attention. And you have Greg, who you always get the impression doesn’t respect Tommy. I mean in real life the guy wrote a book exposing Tommy as a giant idiot.

So how do you make us believe that these guys are actually friends? The whole movie depends on it so you have to make that believable.

This is where lesser writers would’ve crumbled. Neustadter and Weber knew that the way to do this was with an early scene, preferably the first or second scene between the characters. If we convincingly establish this friendship early, we’ll believe it for the rest of the film. That’s how screenwriting works.

And they write this really clever scene in an acting class where Greg struggles to emote. He struggles to leg go. That’s why he’s a bad actor. Tommy, on the other hand, doesn’t give a shit. He emotes from the top of the Empire State Building. Sure, it’s uncalibrated and awkward. But that freedom is what Greg’s missing.

So Greg asks Tommy to do a scene with him to see if he can tap into that freedom, and Tommy challenges him, as they’re eating dinner later, to do the scene right there, in front of the restaurant. Greg is terrified. But Tommy pushes him, and as Greg does the scene, we see him free up and finally, for the first time in his life, let go. It results in a euphoria he’s never felt before. And that’s it. After that scene, we know why Greg will follow this man to the moon and back.

The film does hit some of those LA side-street speed bumps though. Franco’s Tommy impression is laugh out loud funny for the first half-hour, but loses its luster later on. Once those laughs were gone, the movie lost a step. The second half of the film becomes a lot more serious than I expected and I’m not sure that was the right choice. I was hoping for more funny moments of them making the movie. But the infamous, “Oh, hi Mark” scene was pretty much all we got.

This is what I meant when I said that the tone is tricky. You want to keep the audience emotionally invested, but not at the expense of the comedy. And you want to keep them laughing, but not at the expense of emotional investment. If there’s one knock against this film, it might be that it never established a genre. When you don’t have a genre, then when you run into problems, you don’t have a roadmap for where to go. Like, if you’re a comedy and you’re getting towards the end and you’re wondering, “Should this scene be funny or dramatic?” Well, it’s a comedy so it should be funny. This film didn’t have that clear answer and you could feel it at times.

But again, this goes back to the high-powered writing of Neustadter and Weber. They knew that if they got that relationship right, the movie would be able to survive these tonal miscalculations. And we see that in the final scene which is all about Greg convincing Tommy that while he may not have made the film he set out to make, he made something that affected people, and maybe that’s enough. And when Tommy then takes the stage after the screening and says he couldn’t have made the movie without his best friend, I got a little teary-eyed.

That moment alone let me know that this movie was a success.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A compelling relationship at the center of a film can anchor a story to such a degree that the story itself can sustain an adequate amount of messiness and still recover. It’s a great way to hedge your bets if you’re writing one of those films that doesn’t fall into an obvious formula.