I was in the process of reading a screenplay for a consultation a few days ago when the writer e-mailed me with a new draft that contained a couple of minor scene changes. If I hadn’t already started reading his screenplay, he asked, could I please read this new version instead?

This happens a lot. Whether it’s for notes or Amateur Offerings submissions, writers are constantly sending me scripts with a minor update here or a scene tweak there. I’ve always found the practice a curious one. Do these writers really believe that by moving the location of Scene 37 to a bowling alley from a Starbucks, that it will dramatically influence the way their story reads?

And yet, a part of me understands it. Writers want nothing less than the best version of their script read. So even if they come up with five better lines of dialogue in that argument on page 53, they want you reading that script, not the one with the slightly lamer dialogue, which they can’t believe they’d settled on in the first place.

But look at it from a reader’s perspective. Is that really going to affect the way we see the script? Are those five lines really going to be the game-changer that turns your script from “What the hell did I just read” to “Genius?” The truth is, the only way to make a script read markedly better is to make wholesale changes – eliminate some characters, combine others, clarify the goal, tighten up your second act, add more conflict, up the stakes, strengthen your hero’s character arc. A big impact requires big change.

However, this practice got me thinking. What if there WAS a quick change you could make to your script that would make it markedly better? Say you only had 30 minutes. Could you dramatically improve your script in that time? Or, to focus in the question, what’s the fastest change you can make that has the biggest impact on your screenplay?

I didn’t hesitate before I knew the answer.

It’s how you introduce your protagonist. That initial scene where we meet your hero is the most important scene in the movie. Why? Because it doesn’t just affect that scene. It affects how we perceive your hero in every other scene they’re in. Therefore, if you nail that scene, your script becomes markedly better.

Think about some of the great character introductions of all time. Indiana Jones. Hannibal Lecter. Deadpool. Hans Landa. Or even some of the “second tier” great introductions. Juno. Columbus (Zombieland). Thanos. Driver (Drive). Trinity (The Matrix). All of them have the same thing in common. After those scenes, we knew exactly who those characters were, and we wanted to spend as much time with them as possible.

Now that you know how important this scene is, how do you write it? Start by finding a scenario that gives your hero the most potential to shine. For example, let’s say I’ve written a suburban father character. There are so many times during this character’s day that I can introduce him. I can introduce him working in his office. I can introduce him getting lunch. I can introduce him picking up his dry cleaning. I can introduce him making dinner for the family. But do any of those scenes have the potential to make our dad shine? To come off as memorable? Probably not.

But let’s say there’s an important presentation at work today. A 10 million dollar account is on the line. And our suburban dad is giving the presentation. And right before the presentation, his computer conks out. He doesn’t have his notes. But he’s still got to pull the presentation off. It’s not exactly outrunning a boulder in a Mayan temple. But that scene’s going to be way more interesting than any of the others I mentioned.

What you’re ideally looking for is a scene that displays your protagonist’s unique set of skills (or lack of skills!). What makes them worthy of our attention. That’s why the Indiana Jones opening is considered the best introduction of all time. It’s basically a resume of what makes Indiana Jones so great. He susses out traps. He outsmarts tricks. He calmly wipes away problems (deadly spiders). When the worst of circumstances are thrown at him, he finds a way out. Imagine if every character could be introduced this way.

But you don’t have to throw your character into a big action scene to get our attention. One of the best ways to introduce a character is to give them a difficult choice. The Ritual is a great example of this. The main character is given the harrowing choice of either saving his friend, who’s being brutally attacked, or remaining hidden, so he stays safe. Imagine that same character if we never saw this scene. If we only heard about it via backstory. What if the writer had, instead, introduced this character saying goodbye to his wife and kids for the day, like I’ve seen in so many other screenplays? Your perception of who that character was and how interested in him you would be is completely changed. That introduction was everything. (note: this is actually a delayed intro, which I’ll explain in a second)

Getting more specific, there are numerous things you can do in an introductory scene to make your hero impactful. Have them get bullied. The primal desire to sympathize with those who are being unfairly attacked gets us on board with them right away. Outsmart someone. We LOVE characters who can outsmart, outwit, out-clever, someone. Just make sure they’re LEGITIMATELY outsmarting someone and not “movie-logic” outsmarting them. Solo tried to do this by having Han Solo throw a rock at a window to shine light on his light-sensitive alien-captor. We didn’t even know the rules of this room in advance (that the alien was light-sensitive), so Han’s “outsmarting” was lost on us. You can place your protagonist in some kind of peril. It’s better to meet our hero walking the plank than swabbing the deck. You can place your character in any sort of emotionally charged situation and we’ll be drawn in. We meet Natalie Portman’s character in Annihilation in a quarantined debriefing as the lone survivor of an expedition into a disease-ridden anomaly. It’s an intense scene. Show your character being risky, daring, reckless even. We meet Jack as he puts everything he owns on a poker hand for a ticket on the Titanic. And if you can’t think of anything, there’s the old standby – show your character being brave. We love bravery.

Sometimes, the script’s narrative doesn’t allow for the perfect introduction. Take the introduction of Han Solo in the original Star Wars. His introduction is kind of lame. We cut to him already sitting at a table. The movie had to do this because Lucas wanted to keep the story moving. Obi-Wan and Luke needed a pilot. This guy’s a pilot. Let’s intro him quickly and get to the negotiation.

In these cases, you can go for a delayed “secondary intro.” After this scene, they have the famous scene between Han and Greedo. This is everything a good intro scene should be. Han is trapped. He’s got to use his wits to stall the alien. All so that he can blast him to smithereens before the same thing happens to him. After this scene, we’re all in with Han.

If that’s not on the table – if your intro is still lame – ask yourself if you HAVE to introduce your hero where you’re introducing them. It’s important to remember that YOU decide when and where we meet your hero. With a little ingenuity, you can do anything. If they’d began Annihilation traditionally – with Natalie Portman back at home doing her daily chores, waiting for news on her missing husband, we would’ve formed a very different opinion of her. Instead, director Alex Garland manipulated the timeline so that we started in the future, where Portman’s character had already come back from the Shimmer, and was now being interrogated in a quarantined room, complete with contamination suits. A much more interesting way to meet her. So don’t convince yourself that you can’t move things around when you are the writer. You are God. You can do anything. Take advantage of that.

So to summarize – if for any reason you’re trying to improve your script as much as possible and you only have a little bit of time. Don’t focus on altering the dialogue on page 74. I guarantee you that will have zero influence on how the reader receives your script. Instead, ask yourself if there’s a stronger more interesting way to introduce your hero. And if you’ve got that down, ask if there’s a stronger more interesting way to introduce your love interest, or your villain. That’s because the effects of these changes aren’t limited to these scenes. But, rather, they influence how readers experience every scene from here on out.

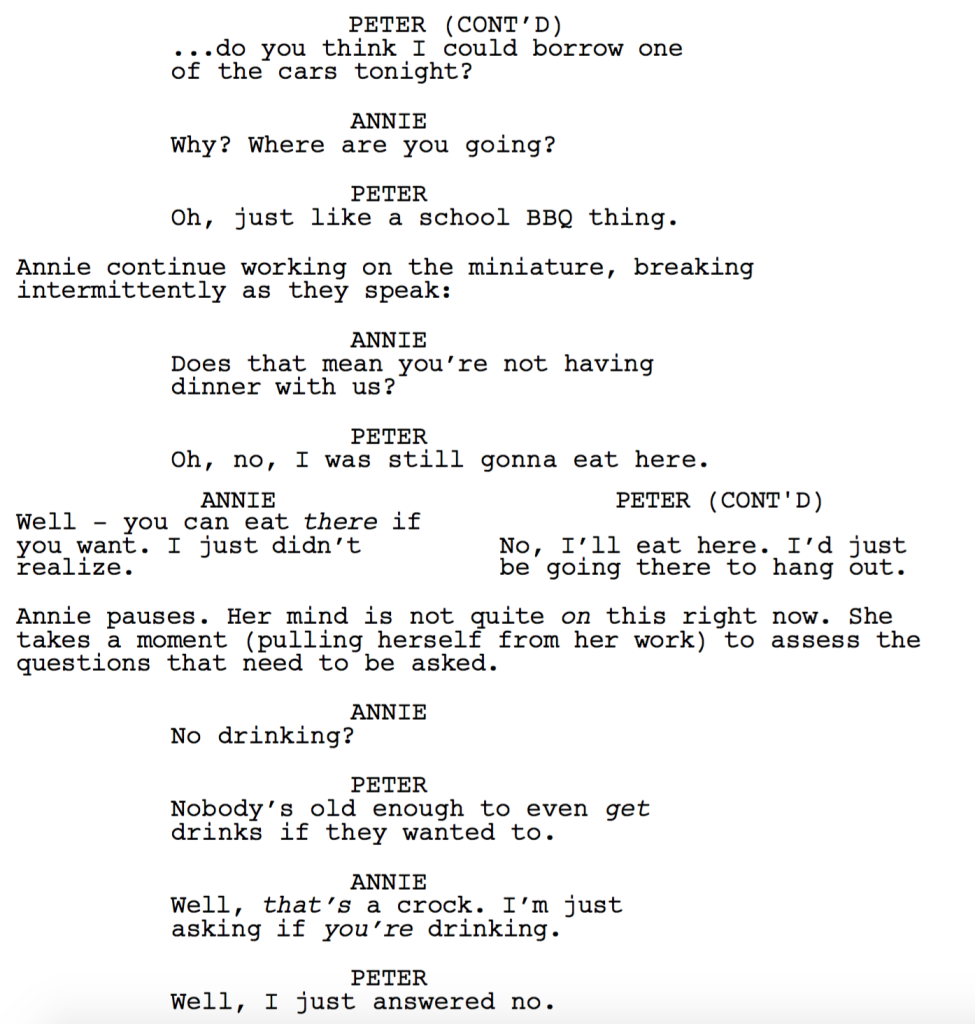

Genre: Horror

Premise: When Ellen, the matriarch of the Graham family, passes away, her daughter’s family begins to unravel cryptic and increasingly terrifying secrets about their ancestry.

About: Billed “The scariest movie of the year!” Hereditary comes out this weekend. It made waves after a few festival screenings, with many coming away saying that we’d found our next great director. That director, Ari Aster, is also the writer.

Writer: Ari Aster

Details: 118 pages (for a horror script?!?)

I’d been hearing a lot of good things about this movie. It’s the scariest movie ever. It killed at all the festivals. It’s taking A24 to the next level. It unleashes a new visionary director.

I will concede that AS A MOVIE these things may be true. I don’t know. I haven’t seen it. But as a screenplay? This is one of the worst horror scripts I’ve read in a long time. I am talking that if this script competed on Amateur Offerings, it wouldn’t have even beaten out the other four scripts that week. It’d be the 2-3 vote script a few kind-hearted souls offered the writer encouragement on. “Keep working at it. Writing takes time!”

This goes to show the power of being a writer-director. You can get a piece of shit script straight through the system cause you’re directing it yourself. So congrats to Aster. Cause if he wasn’t directing this script, it would’ve ended up in the digital cemetery.

Wife and mother, Annie, husband and father, Steve, teenage son, Peter, and teenage daughter, Charlie, are all reeling after the death of Annie’s mother, who had dementia and lived in the house up until her passing.

But truth be told, this family was fucked up long before that. Weirdo outcast Charlie cuts off the heads of dead animals and keeps them in a shoebox that she hides in the treehouse she sleeps in, even though it’s winter and she nearly dies of pneumonia every night.

Peter hates his crazy mom because, as we learn from one of the many random monologues she spews, he woke up one night covered in paint thinner with Annie standing over him with a match.

Charlie has a nut allergy. The surest way to identify a newbie screenwriter (besides naming a female character with a male name) is the old nut allergy trope! And we get a LOT of reminders of that nut allergy. Hmm, I wonder why. Could it be that, at some point, Charlie is going to accidentally eat something with nuts in it?

Hold your horses, folks. Cause this is the nut allergy scene to end all nut allergy scenes. Peter brings outcast Charlie to a party because, yeah, teenage boys desperate to fit in with the cool crowd always take their weirdo animal-head-loving younger sisters who are often mistaken for a guy to parties. Totally sounds like real life to me.

But we need that nut allergy scene! So she’s coming with.

Charlie, who normally talks to nobody, is so taken by the chocolate cake being baked in the kitchen (cause, you know, teenagers always bake cakes at high school parties), scarfs several pieces down, only to find out afterwards that the cake had nuts in it!

A freaked out Peter throws her in the car and tries to rush her to the hospital, during which Charlie sticks her head out the window to enjoy the wind – since that’s what you do when you’re dying, enjoy a nice breeze – only for Peter to see a deer, swerve out of the way, and for Charlie’s head to hit a telephone poll and DECAPITATE.

I’m not lying. This happens.

Oh, this is the good part. Peter ignores this, drives home, parks the car, and goes to sleep. Because… well because this situation WAS RIPPED OFF FROM A REAL LIFE STORY THAT HAPPENED A DECADE AGO AND MADE NATIONAL HEADLINES. So I guess we’re just randomly ripping off real life fantastical events to get our shock on.

It only gets worse, folks.

The script has NO POINT. NO DESTINATION. The writer has no concept of how to craft a story. So we just follow the characters as they wander about their lives until the writer comes up with something he thinks may be scary. Seances are scary, right?! Let’s do one of those then! So it’s time for a seance where Annie talks like Charlie.

Hey, what happened to the grandmother? The one we’re told is the reason this story exists? Ehhh… not relevant. But we’ve got sleepwalking! Lots of people sleepwalk in this movie. Why? Cause sleepwalking is scary! That’s the only determinant for inclusion in Hereditary. Something scary? Include it. Something that crafts compelling characters or a story with a purpose? Throw it out.

I suppose the driving force of the story is the growing animosity between Peter and his mother. We’re supposed to want to see how that’s going to end? But I never bought it. Not for a second. Why? Because there wasn’t a single honest beat between this family. They talked like they’d all met each other a week before the movie started.

And everything is manipulated. Nobody talks TO each other. The dialogue is used solely as a means to justify an improbable moment or reveal relevant backstory. For example, Peter, who has never once in the movie expressed any interest in talking to his mom or seeing how she feels, out of nowhere starts yelling at Annie to tell him what she “really feels.” This allows Annie to monologue an admission that she hates her son and never wanted him in the first place. When you make characters do things that they wouldn’t normally do in order to make something happen that you need to happen, you are CHEATING. You are LYING. You are undermining the reality of your characters.

But I kept on.

There were so many things that irritated me in this script. Like when we cut to the decapitated head of Charlie the next day, it has ants all over it.

Ants?

IT’S BEEN WINTER THE WHOLE MOVIE!!!

Are these winter ants??? Are you creating new species of ants?????

This may seem like a nitpick but it embodies everything that is wrong with this script. The writer liked the image of ants on the head so much that he was willing to disregard everything he’d set up beforehand. Style over substance.

The only thing that saves this from being the worst horror script in existence is the last 20 pages, where we finally get some unique imagery, like a possessed Peter being ripped around by a demon in his classroom. But it’s still a sham. It’s still style over screenplay. Every moment is looked at through the lens of, “What’s the most shocking image I can come up with right now?” Not, “How can I explore these characters in an interesting way?” or “How can I mine my concept to create an interesting story?”

This script, with its lack of originality, with its shock-first mindset, with its inauthentic family relationship, with its wandering second act, with its blatant transperency, made me physically angry. It’s everything I preach not to do. I shouldn’t be surprised. This is the same company that made “It Comes at Night” and “The Witch,” two pretty to look at auteur-driven movies with horrible screenplays. A24, at least when it comes to horror, might want to hire a few more producers who understand screenwriting.

[x] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The BIGGEST horror screenplay sin is prioritizing imagery over story. That’s the blueprint for writing a terrible horror film. A blueprint this writer followed from page 1 to page 118.

Genre: Buddy Cop?

Premise: (from Black List) A rogue cop suffers a gunshot wound in 1987 and wakes from a coma thirty years later, where he is partnered with a mild- mannered progressive detective – his son.

About: Former real-life cop Will Beall burst onto the scene in 2009 with the highly touted spec, “L.A. Rex.” A screenwriting neophyte, Beall didn’t even know that dialogue was supposed to take place vertically. So all the dialogue was side by side. He would eventually write Gangster Squad, create the Training Day TV series, work on the upcoming Venom, and has sole screenwriting credit on the upcoming Aquaman. So I’d say life’s going well for Mr. Beall. This spec of Beall’s finished with 8 votes on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Will Beall

Details: 131 pages

If you possess the urge to overwrite, the push to pontificate, the desire to scribble endlessly between the margins, my friends, I have found your champion. Will Beall is on a mission to write the ultimate ‘fuck you’ page – one without a single square inch of white space on it.

If I’m being honest, I don’t think Will Beall has ever read a script. If he had, he’d surely know how annoying it is to consume jurassic sized paragraph after jurassic sized paragraph. It’s exhausting. And it’s self-defeating. Once paragraphs start getting too long, readers just skim them. So why write that way if no one’s going to read it?

27 year old Sam Braden is the best (and wildest) cop in 1987 Los Angeles. And he loves his job. There’s nowhere he’d rather be than some titty bar busting a high-profile coke deal. It has some residual effects on his family life. He’s not around all the time. But what can he do? The cop life is too addictive.

That addiction ends up being Sam’s undoing. After answering a routine call, a man in a mask kills his partner and shoots Sam in the head. Cut to present day. Sam’s recently come out of a 30 year coma and has severe brain trauma. That is until they try an experimental procedure on him that magically cures everything.

Sam meets his now 27 year old son, Sean, who’s a cop himself. Unlike the wild Sam, however, Sean is a calm and calculated lawman. And he’s pissed that Sam wasn’t around more when he was growing up.

Sam can’t stand being on the sidelines so he reapplies for his cop license and within a week, he’s teamed up with is reluctant son to fight crime.

Naturally, Sam is all ‘shoot first and ask questions later’ while Sean is all, ‘ask questions, check the manual, and don’t shoot at all.’ The two stumble across some high grade guns that have made their way into the gang ranks, and try to find the source.

(spoilers) They learn that these guns are connected to a plan by their police chief to turn the LA police force into a military style mercenary outfit that, for some reason, first involves blowing up half of LA. It’ll be up to our father and son team to stop them. But can their styles mesh long enough to pull it off?

Holy Bonkersville.

This script is freaking ALL OVER THE PLACE! I don’t know where to start. First of all, Beall does know that this is a comedic premise, right? So then why is it a drama?? Straight out of the gate you’re going to piss off your audience who think they’re coming in to see something else.

And the plot steps all over the premise. With a concept like this, you want to create a bunch of scenarios that juxtopose the styles of a loose-cannon 1987 cop and a by-the-rules 2018 cop. We only get a couple of those scenes and the rest of the script focuses on an unrealistic plot to destroy half of LA in order to militarize the police force.

The odd choices don’t stop there. We get a futuristic military drone that’s based on the Terminator flying robotic killing machines. Um, what?? It’s enough to make me wonder how Beall is getting all this high profile work. Not only is the plot all over the place. But the script is really hard to read. Each page is so dense it feels like a homework assignment due tomorrow morning in first period. I thought reading was supposed to be fun.

I suppose there are a few reasons for Beall’s success. First of all, he understands the world of cops better than any other writer working in Hollywood right now. And that’s worth something. Most writers do their cop writing based on the Die Hard franchise. That’s never an issue with Beall. Here’s Sean rolling up on a clueless bank robber:

“You really don’t know what the hell you’re doing, do you? You don’t lay your hostages down on the floor. You stand them up, so the SWAT snipers will have to shoot through them to get at you.”

I mean, who the fuck knows this besides a real cop?

He’s also good with dialogue in general. I would suspect that’s the main reason he gets hired.

“The fuck are you, a doctor?” “Right now, I’m the difference between five years with good behavior and a lethal injection. And I just bought you about ninety seconds to make up your mind before this guy bleeds out and you’re a slam-dunk death penalty for a DA who’s up for reelection.”

But everything else here feels like it was vomited onto the page, a series of tonally mismatched sequences in search of a movie. I mean, the opening scene, which takes place in a room with a giant aquarium, has a shootout with sharks attacking our cops. Then we get this ultra-serious “scientifically accurate” depiction of how Sean recovers from his coma, which is later followed by a goofy one-on-one battle between Sean and a state-of-the-art military drone which is later followed by a serious investigation into how gangs are getting their hands on military grade weapons.

Is this a comedy or isn’t it?

Beall should’ve kept the plot bare-bones and focused on the differences between the cops. There’s a ton to mine from there. In the last 3 years alone, there have been insane changes to how cops operate. Imagine having 30 years of changes to play with. You could do so much.

I have a theory about how this script came together. I think Beall had two different scripts, one about a 1980’s cop who wakes up in the present day. And another about a military takeover of the LA police force. He didn’t feel like either of them worked on their own. So he combined them.

I’ve seen the “idea-combining” strategy before and it rarely works. The reason is that you don’t want ideas competing against each other in a screenplay. All of your ideas should be working together. Even if Beall rewrote this to death to fuse the concepts into something more harmonious, I don’t see it working. These are separate concepts that require their own screenplays.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Read more scripts. This SHOULD be obvious advice on a site like this, but I get the feeling aspiring screenwriters don’t read enough. The reason you read scripts isn’t only to figure out what works, it’s to figure out what drives you crazy so that you don’t do it yourself. A lot of writers will say stuff like, “The 3-line max paragraph rule is dumb” or “A 130 page script is fine if that’s how much time the story needs.” Read a hundred scripts and tell me how you feel about these opinions then.

What I learned 2: Make adjustments to names if needed. The two main characters here are Sam and Sean. Can you imagine reading 500 dialogue entries starting with two names that are so easy to mix up? So Beall referred to Sam by his last name, “Braden,” and Sean by his first.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: After a young woman is left for dead in the desert by three men, she hunts them down one by one.

About: Writer-director Coralie Fargeat’s surprising first film is generating a lot of conversation. Is it a “synthesis of exploitation and feminism,” like New York Times film critic A.O. Scott labels it? Or is it the embodiment of poor taste? The film is out now on video-on-demand so you can decide for yourself.

Writer: Coralie Fargeat

Details: 108 minutes

Today I tackle the ultimate screenwriting question, the one that will determine whether you toil away in amateur screenwriting obscurity for the rest of your life or become one of the lucky few to ascend into the Hollywood ranks.

How do you take a premise that has been done so many times before and make it fresh?

Because let’s be honest. Every story has already been told. Which means whatever script you’re working on, it’s going to be something audiences have seen dozens, if not hundreds, of times before. Your ability to find a fresh angle on these stale ideas is the key to your success.

There’s no setup that’s been around longer than the revenge thriller. Bad guy does something horrible to hero or people hero knows. Hero enacts revenge. If there is ever an idea that embodies “been there, done that,” it’s this one.

So before I turned on “Revenge,” I queued up several Youtube videos I’d been meaning to get to. Based on prior experience, this flick would be lucky if I didn’t turn it off by the 20 minute mark. But the only thing that got turned off was my skepticism. “Revenge” is one of the best revenge films of the 21st century. So much so that I didn’t look at the time once during the film. Afterwards, I sat there in a daze. How was it that a writer could create something so exciting out of an idea so unoriginal?

The plot follows a French millionaire, Richard, who whisks his American girlfriend, Jen, away to his trendy desert oasis for the weekend, where the two plan a wild 48 hours of romance.

Their plans are interrupted, however, when Richard’s creepy hunting friends, Stan and Dimitri, stop by a few days before their annual hunting trip. Stan and Dimitri are surprised to see that Richard is keeping female company considering the fact that he’s married with children. The four of them end up having a fun night, though, drinking and dancing until they pass out.

The next morning, while Richard is off taking care of some hunting license issues, Stan attempts to seduce Jen, and when she refuses, rapes her. When Richard comes back, Stan cops to the crime.

But instead of beating the life out of his supposed best friend like we expect, Richard worries that Jen might say something once back in the states. Fearing that his wife would find out, he decides to kill Jen. Jen catches wind of this plan early enough to make a run for it, but the guys catch up to her, cornering her at a cliff. She falls and lands squarely on an exposed spike-tree, the top of which impales her stomach.

Richard constructs a plan. Go hunting over the next couple of days like they normally do so as to have a cover story, and then they’ll clean up the Jen mess afterwards. However, when they later arrive at the tree that impaled Jen, she’s no longer there. Over the next 24 hours, Jen will hunt these men down, one by one, to enact her revenge.

Let’s get back to my original question: How do you take a premise that’s been done so many times before and make it fresh?

The answer is simple. You color as many of the elements differently as you can.

Each screenplay is a combination of individual elements: characters, set pieces, circumstances, locations, dialogue, plot points, themes, twists. The more of these elements you can color with a different shade, the more original your take on the premise will be.

Take the location. I’ve seen revenge thrillers that have taken place in cities. I’ve seen revenge thrillers that have taken place in forests. Until this film, I’ve never seen a revenge thriller that takes place in a desert.

That one choice immediately separates Revenge from its predecessors. Not just visually. But there’s nowhere to hide in a desert. And since these movies are all about hiding, it forces the writer to find unique ways to frame the kills.

The setup to this film was also a different shade. I was assuming one of two things would happen. Either we’d learn that all three men had planned to bring Jen out here to rape and kill her. Or that after Stan raped her, he would also kill Richard to prevent retaliation.

These are the kinds of blunt choices most screenwriters make.

The reveal that Richard is married changes everything. After Stan assaults Jen, Richard is furious with him, but not enough to jeopardize his marriage and family. This puts him in a mindset where Jen is now a liability. He doesn’t want to get rid of her. But circumstances dictate that he must.

The problem with so many revenge thrillers is that they’re painted with this blunt brush. “I must kill you because me bad guy.” Creating a more complicated situation, one that involves a little more nuance, helps make the story feel more realistic. The fact that Richard is doing this to protect something that it’s his fault he jeopardized in the first place makes him so much more sinister.

In addition to shading the elements differently, the script aces the basics as well. In any revenge thriller, you need great villains. If we don’t hate the villains with every fiber of our being, we’re not going to be invested in the revenge. The act of what was done to Jen combined with the betrayal of someone she trusted was what makes us hate these guys so much. They are true villains. So of course we’re going to watch with baited breath as Jen hunts them down one by one.

But making Jen the ultimate underdog was the best choice of all. Not only is she a city girl who doesn’t know the first thing about killing. Not only is she injured beyond comprehension. But she’s going up against three HUNTERS. Three men with top-of-the-line hunting equipment and experience killing living things.

In screenwriting, the magic trick is to create the belief that there’s no way your hero can win. The odds are stacked too highly against her. That’s what keeps us turning the pages. We want to see if Jen can beat these odds. Fargeat does an amazing job of this.

I also like that it isn’t that Jen WANTS to kill these men. It’s that she HAS TO kill these men. That’s an important distinction. “Want” is fine. It drives most revenge films. The hero won’t feel complete unless the bad guy pays for what he’s done. The problem with “want” is that there’s a sadness to it. They kill the guy but what’s really been accomplished? William Monahan wrote this Mel Gibson revenge flick 8 years ago called “Edge of Darkness” that exemplifies this problem. Gibson hunts down and successfully kills the people who killed his daughter, but we don’t feel any better at the end. The daughter is still dead.

The reason that “has to” is so great is because the revenge has a purpose. Our hero doesn’t survive UNLESS she kills the villains. And that ultimately makes the kills more satisfying. “Revenge” accomplishes this rare feat of making a revenge film feel good when it’s all said and done.

Probably the biggest takeaway here is the reminder that what you do in the first act – particularly with the characters – is the key to making the rest of the story work. The last 60% of this movie is pure pursuit. Very little dialogue. Just Jen hunting the men and the men hunting her. But we don’t get bored because Fargeat nailed that first act. She made us love the hero. She made us hate the villains. She constructed a scenario that was just unique enough so that we feel like we’re watching something original. And from there, all we care about is Jen winning.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Something we talked about with Black Panther was making the dynamic between protagonist (T’Challa) and antagonist (Killmonger) personal. That helped separate Black Panther from so many other comic book movies. Same deal here. If these were random men who assaulted Jen, we wouldn’t care as much. It’s that it was a man she trusted and cared about that’s doing this to her that makes us so angry. That makes the revenge so sweet.

By the way, Black Panther is another great example of painting familiar scenarios with different colors to create an overall original experience.

DIALOGUE WEEK IS HERE! – All this week, I’ve been breaking down dialogue scenes from the movies you love. Monday’s Dialogue Post is here. Tuesday’s post is here. And yesterday’s post is here.

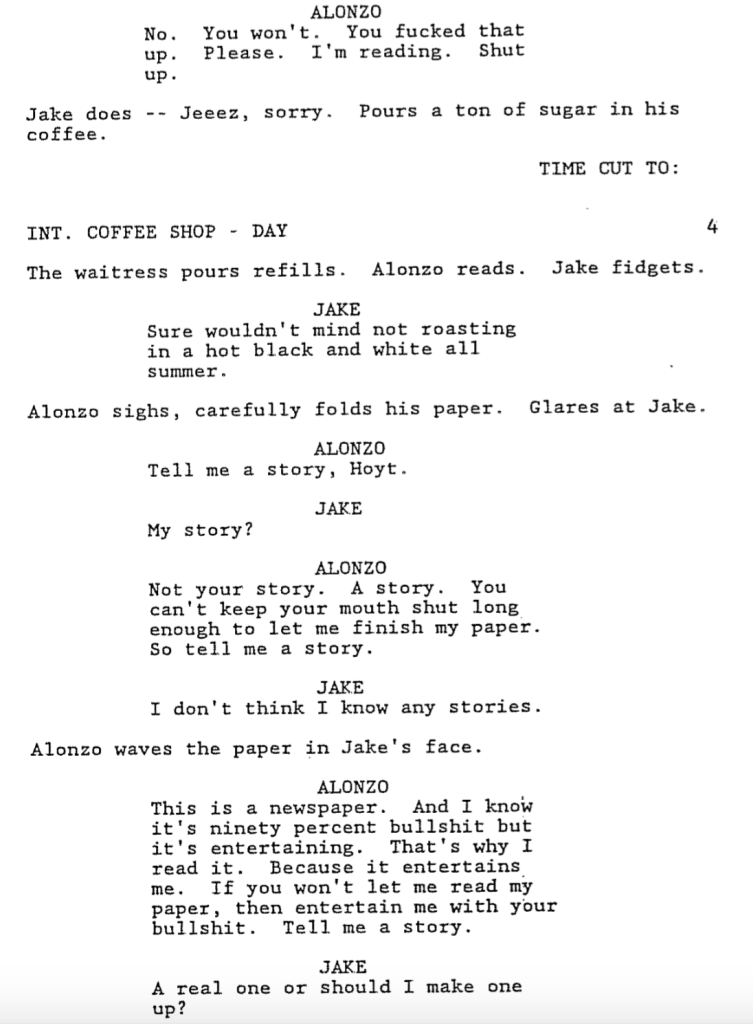

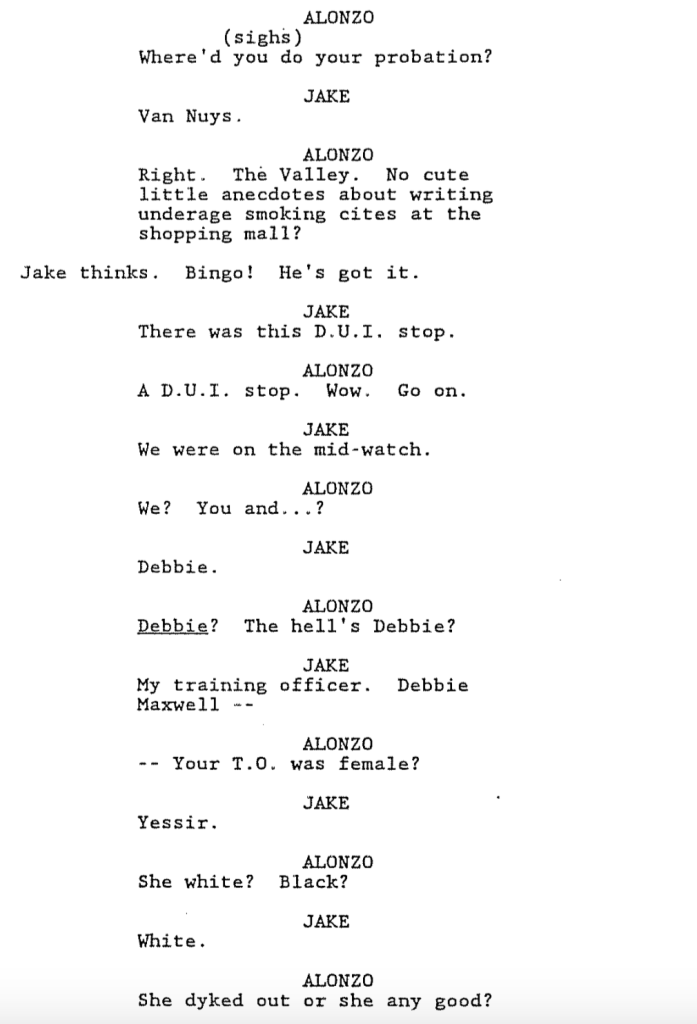

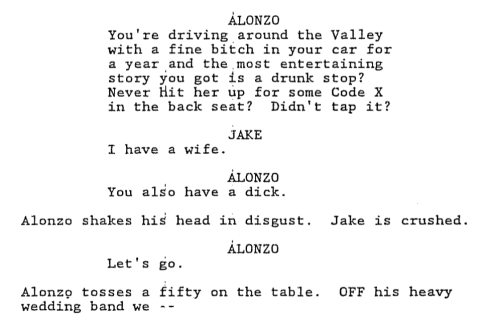

If you want to go to dialogue school, check out Training Day. It’s basically a 120 minute dialogue scene. Which brings us to our first lesson. Don’t focus on writing great individual dialogue scenes. Focus on creating great characters who can then write the dialogue for you. Alonzo is the ultimate dialogue-friendly character. And Jake is the ultimate straight man. Put those characters together and you have dozens of scenes where the dialogue writes itself. Let’s check out their famous first meeting together. For those who haven’t seen the movie, it’s about a young cop’s first training day with a veteran narcotics officer.

Okay, let’s jump into the easiest way to write a good dialogue scene. Are you ready? Give us one character who doesn’t want to talk and one character who does. That’s it! Boom! You do that, you will write good dialogue. I promise you. And that’s the whole premise of this scene. Jake wants to talk. Alonzo doesn’t.

I could stop there and you’d be halfway towards dialogue mastery. But I want to revisit this week’s theme. Which is that the best dialogue comes from what you’ve done BEOFRE the scene. Not during. We’ve built this entire movie around a dialogue-friendly character in Alonzo. He’s opinionated. He’s brash. He’s colorful. He’s un-p.c. He says the things you’re not supposed to say.

We then placed him across from a straight man. Dialogue-friendly characters work best with straight men. Two dialogue-friendly characters is like having two chefs in the kitchen. With that said, 2 DF characters can work. In Silver Linings Playbook, Pat and Tiffany were both dialogue-friendly and their scenes were great. But generally speaking, the rhythm of good dialogue follows a dominant and submissive pattern.

Which segues nicely into our next topic: power dynamic. Power dynamic is HUGE when it comes to dialogue. The very nature of somebody being “in charge” creates an imbalance. And that’s where the tension is. Tension is conflict. Conflict is drama. Drama is entertainment. In this scene, the power dynamic is obvious. It’s built into their job descriptions. But there’s a power dynamic to every conversation. Yesterday, the power dynamic was with the parents. They were in charge of the conversation. Chris was merely trying not to fuck up. In The Big Lebowski scene, Walter was on top of the power ladder, The Dude was in the middle, and Donny was on the bottom.

In this scene Alonzo’s power is SO MUCH HIGHER than Jake’s that Jake’s walking on eggshells the whole scene, which is what makes the conversation so fun. You can see Jake trying to say something – ANYTHING – to get Alonzo’s approval. If Jake and Alonzo are on the same power level, this scene doesn’t work.

It shouldn’t need to be said that dialogue reveals character. Which means you should be looking for opportunities to tell us about your character through the lines they deliver. Especially early in the screenplay, when we don’t know them yet. It just so happens there are a couple of prominent character revealing lines in this scene.

Alonzo is fed up that Jake won’t stop talking to him, so he demands that Jake tell him a story. Jake mumbles out that he does’t know any stories and Alonzo doubles down. Tell me a fucking story. “A real one or should I make one up?” Jake replies. I love this line because not only is it unexpected. But it reveals how indecisive and eager to please Jake is. I know everything I need to know about this character after this line.

Ditto Alonzo with his response to Jake’s story. Alonzo has no issues with telling Jake that his story sucked (he’s mean). And that getting laid is more important than preventing murder (seriously warped moral compass). In one sentence, we know just how screwed up and ruthless this man is. That’s good writing.

Let’s get into some minutiae. I love how Ayers says that Alonzo never stops looking at his paper during the conversation. It creates this literal barrier for Jake to bang up against for the first half of the scene. A lot of amateur writers assume you need to create the perfect circumstances for a conversation. It’s the opposite. You’re trying to find the angle that creates the most un-ideal circumstances for conversing. By forcing Jake to talk to a wall, it injects one more layer of conflict into a situation that’s already drowning in it.

Another example of this would be two people who meet at a loud club. They can’t hear each other. They have to keep saying, “What??” They misunderstand words, which leads to strange conversation tangents. That’s always going to be more fun than if they meet in a quiet room with no distractions.

I also love this exchange. “Have some chow before we hit the office. Go ahead. It’s my dollar.” “No, thank you, sir. I ate.” “Fine. Don’t.” Alonzo could’ve questioned what’s wrong with Jake here (“Who doesn’t eat at a diner?”). He could’ve challenged him (“You knew you were meeting me for breakfast and you already ate?”). Instead, he uses two words. “Fine. Don’t.” It’s savage. I actually shivered when I read those words. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the fewer words you use, the better. You don’t always have to craft a wonder-line.

Speaking of wonder-lines, there’s one flashy line in this scene. The newspaper line. And that’s appropriate. You shouldn’t be trying to win the lottery with every line. The very act of limiting yourself to one killer line ensures it will stand out. “This is a newspaper. And I know it’s ninety percent bullshit but it’s entertaining. That’s why I read it. Because it entertains me. If you won’t let me read my paper, then entertain me with your bullshit. Tell me a story.”

How do you write a line like this? Because I read a lot of amateur versions of this line. They come out more like, “Now you done fucked up. I can’t focus no more. All because you think you’re more entertaining than a newspaper. So if that’s what you think, then go ahead. Entertain me.” It’s clunky, not as clean. And doesn’t end with the same decisive POP that Ayers line does.

This is a case of a writer paying attention to his environment. You have this newspaper here. It’s already a major part of the scene. Let’s keep using it. But how can we use it to craft a great line? Start by asking questions. “What is a newspaper?” (It’s mostly bullshit) “Why is my character interested in this newspaper?” (it’s his calm before the storm) “What’s in here that he needs so badly?” (nothing really. But it’s one of the few things that entertains him. And since not many things entertain him, he values it).

You now have some PIECES you can use to form a line.

The answers to those questions pretty much form the basis of the first 75% of the line. Ayers then gives the line extra pop at the end by adding some wordplay. Entertainment and bullshit were featured words at the beginning of the line, so he brings them back at the end (“If you won’t let me read my paper, then entertain me with your bullshit”). There’s no science to this stuff but that’s one way of arriving at the line. Of course, for some writers, this stuff just comes naturally. Lucky bastards.

Finally, what I love so much about this scene is that while Denzel got a ton of credit for his performance, the truth is, it’s all there on the page. I don’t see that often. A lot of writers are wishy-washy and it opens the scene up for lots of interpretation. There’s no interpretation here. Any actor reads that beat of Alonzo keeping that newspaper up between him and Jake, and they know exactly who this character is and how to play him.

What I learned: Don’t over-describe pointless actions during heavy dialogue scenes. The less action you write, the more we can focus on what the characters are saying. Ayers writes barely any action here, and when he does, he keeps it to one line, except for a couple of times when it reaches one line and a quarter.

Now that you’ve read the scene, check out the finished product.