This is one of the toughest questions screenwriters face. You spend 6-12 months writing a screenplay. You send it out to a few close friends, maybe a couple of industry contacts, and the initial feedback isn’t bad, but it isn’t great either. One thing is clear though. Your script isn’t the runaway hit you thought it was. No worries. You take that feedback, do some rewriting, address the major concerns, come back, send it out to those people again (if they agree to read it that is) and the response is… still a bit tepid. “Yeaaahhhh. This is a littttlllle better. But I don’t know. There’s something missing.”

All of a sudden, a terrifying prospect hits you. You may have just wasted an entire year of your life on a screenplay that nobody wants a part of. Do you ditch the script and move on to the next one? Or do you put in yet another rewrite in the hopes that you can elevate the script to the potential you know it has?

Before I help you answer that question, I want to say that making this choice is an imperfect process. A lot of it is based on feel. And I’ll give you a prime example of that. There was a script I reviewed a couple of weeks ago called “Final Journey.” You may remember it as the “Eskimo Hand Job” script.

I would later learn that the writer had written that script a decade ago. It placed well in some contests but nothing came of it so he moved on, writing a dozen other scripts over the years. Then he decided to dust the script off and enter it into a few contests. At Page, the script tapped out in the third round, but one of the judges was a respected manager who absolutely loved it. That love led to a signing, the manager blasting the script around town, and the script subsequently making the Black List.

The point is, all script success stories funnel back to an early champion, someone with notoriety who can bring attention to the script. And you never know who that person is going to be. However, there are ways if to gauge if your script is good enough to find a champion. The last person you want to be is the guy parading the same script around town year after year, insisting that its genius hasn’t been recognized yet.

So, here are some tips you can use to gauge whether you should keep pushing your script out there or move on to the next one.

Is this one of your first three scripts? – I’m not going to say it’s impossible to write a great script in your first three tries. But it’s hard. Those first three scripts are somewhat of an education period for screenwriters that help them become familiar with screenwriting’s unique format. This is not the determining factor in whether to move on or not. But it is a factor. If there’s little interest in your script despite a lot of reads and it happens to be one of your first three scripts? Consider moving on.

Have you done everything in your power to get your script out there? – I’ll never forget this one newbie writer who spent three years writing a fantasy script, then afterwards, sent it to the five industry contacts he’d accumulated in that time (all of them friends-of-friends-of-friends), and when all five of them came back with, “No thank you,” he packed up, said that Hollywood was a town run strictly by nepotism, and moved back home. I mean, come on! You have to understand that this is a town addicted to the word, “No.” Steven Spielberg gets told no. JJ Abrams gets told no. As a nobody, you’re going to get a lot of nos. The only way to combat this is to explore every avenue – contests, online services, Scriptshadow, friends of friends in the industry. If you haven’t gotten your script out to at least 10 people (and preferably a lot more), you have no idea if your script is worth continuing to pursue.

Identify honest feedback – Part of figuring out whether to stay in a script relationship or cut ties is gauging feedback. If the feedback’s good, stay. If it isn’t, go. Here’s the problem though. Not all feedback is honest. In fact, most feedback is given with kid’s gloves, so as not to hurt the writer’s feelings. For this reason, whatever a reader’s evaluation is, assume it’s worse. I’ll never forget one of my friends giving me nice polite feedback on a script once and thinking, “Wow! This script isn’t that far off!” Five years later I was out drunk with that same friend, and the script came up. He launched into this randomly angry monologue about how my script was nearly impossible to get through because of how bad it was. He ended with, “I’m so glad you moved on from that thing.” Yikes. I had no idea he hated the script that much. It was a reminder that people don’t want to hurt your feelings. With that in mind, there are a few things to look for during feedback. If feedback (written or oral) is polite, repressed, or apathetic, you’re in trouble. If there’s genuine excitement, an eagerness to recall favorite moments, or the reader wants to know what you’re going to do with the script next, that’s an indication it’s a script worth fighting for. (side note: always consider the source. If you send your comedy spec about a man who sleeps with 100 women in one weekend to a woman who identifies herself as “The Internet’s #1 SJW,” she’s probably going to hate your script no matter what)

How big are the script’s problems? – In trying to figure out if you should rewrite your script yet again, you need to identify how much work is involved. The more work, the more time. The more time, the more you should consider the script a sunken cost and move on. If you’re hearing feedback like, “The entire second act drags,” or, “I don’t understand your main character,” that’s major rewrite territory there. If it’s stuff like, “You need an extra scene to beef up the love story” or “I would combine 5th Most Important Character with 7th Most Important Character,” those changes can be made fairly quickly.

Be honest with yourself – Every script is a like a baby to a screenwriter. It doesn’t matter if he’s the ugliest baby in the city. He’s still YOUR baby. But the difference between an ugly baby and an ugly screenplay is that you don’t have to raise an ugly screenplay. So do me a favor. Step outside of your subjective reality – the 500 hours you’ve spent on the screenplay, the trailer you can’t wait to see in the theater for the first time, that brilliant devastating scene at the end that’s going to have the audience in tears – and look at the objective reality. Are the people reading your script feeling even a fraction of what you’re feeling? One of the biggest reasons writers stick with scripts that don’t deserve to be stuck with is that they’re not honest with themselves. Stop looking at your script through rose-colored glasses.

If this article has helped you realize it’s time to move on from your current screenplay, I have a couple of happy thoughts to leave you with. Every time you write a new screenplay, you become a better writer. So you should be excited about writing something new. Also, no screenplay is ever truly dead, as the Eskimo Handjob script reminds us. Once you sell a script, tons of people are going to want to read whatever else you’ve got. That’s when you bust out your old stash of screenplay gems.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: When the city’s worst cops are asked to run a simple errand for their Captain, they get mixed up with a dirty cop who’ll do anything to save her ass.

About: This spec sold earlier this year. It comes from the writing team of Jim Freeman, Brian Jarvis, and the actress/writer with the best name in show business, Fortune Feimster. Taking full advantage of the female-led comedy craze, the trio built their cop comedy around three female leads. The writing team has been making a name for themselves in television for years. This is their first big feature film.

Writers: Jim Freeman & Brian Jarvis & Fortune Feimster

Details: 105 pages

They’re calling it the death of the R-Rated Comedy.

With The House being dead at the craps table this weekend, and R-rated Baywatch tanking, and Rough Night, and Fist Fight, and Chips, Hollywood has officially announced that the R-rated comedy is dunzoes. It’s time to move back to lighter fare that carries the magical PG-13 rating which opens up films to a much bigger box office take anyway.

But is the R-rated comedy dead?? Is it?? Or were these simply five of the most unimaginative uninteresting ideas that could’ve possibly been dropped into the marketplace? Nobody wears a blue t-shirt to a Black Tie Event, do they? I have no idea what that means.

But what Hollywood’s really afraid of is the state of female-led comedy. That’s been their greenlight meal ticket for three years now. In a world where everyone loves to tell you ‘no,’ nobody wants the only surefire way left to get movies made closed down for good. You can’t take the baby out with the bathwater. I don’t know what that means either. At first glance, Bad Cop Bad Cop looks like it’s going to be the R-rated female-led comedy that SAVES THIS GENRE.

But is it? Is it?

28 year old Molly, a tough and pretty overweight cop, and her partner, 27 year old Devon, a jovial overweight cop, are both terrible cops. We meet the two in a parking lot as they walk past a car with a dog in it and all the windows rolled up. Determined to save the in-danger furball, Devon bashes the window open, scaring the dog, who runs to the other side. Molly bashes the other window open, sending the dog back to the first side, now in the front, forcing Devon to bash that window, and then Molly the other front window.

While the two are distracted by the arrival of the car’s owner, the dog jumps out of the sunroof and runs away, a sunroof that had been open the entire time.

Back at the precinct, their Liam Neeson like Captain reiterates to them that they’re the worst cops in America and that’s why they’re going to be on errand duty for the rest of their careers. In fact, he wants them to run an errand for him right now – go pick up his son from DJ College.

Meanwhile, we meet Frankie, a badass female cop who embodies everything the Captain wants a cop to be. Devon and Molly realize that if they could just be more like Frankie, they’d escape errand duty for good.

As fate would have it, they run into Frankie after picking up the Captain’s son. Frankie wants them to help her discipline a criminal, encouraging them to rough him up so he never breaks the law again. Molly and Devon think this feels an awful lot like harassment, but they really want to impress Frankie so they do everything they’re told (which includes making the man strip naked and shave off his pubes).

What they don’t know is that Frankie was recording the harassment on her dashcam, which she now uses to blackmail Devon and Molly into helping her take down a major drug dealer. You see, Frankie owes a gangster a quarter of a million dollars by the end of the day, and getting those drugs so she can sell them is the only way she comes out of this alive.

What Frankie will learn is that employing the WORST COPS EVER to get her out of this dilemma probably wasn’t the best idea.

Bad Cop Bad Cop isn’t bad. In fact, I think its two leads, Devon and Molly, are quite funny.

But it is plagued with a major problem.

It doesn’t know what its concept is.

At first I thought this was going to be about two terrible cops who try to get the job done and, against all odds, pull it off. Not the most original idea. But simple concepts like that, executed well, can work in comedy. That was basically the premise for The Other Guys.

Then Frankie is thrown into the mix and it becomes this sort of comedic Training Day but with women scenario. An innocent new female cop paired up with a dangerous veteran female cop who doesn’t play by the rules – I could see a movie in that. But things get confusing with it being the dirty cop paired up with our two bad cops.

So isn’t it then Bad Cop Bad Cop… Bad Cop?

Stuff like this may seem trivial to screenwriters but this is a big deal. Your concept in a comedy needs to be clear because 80% of the jokes will be based around that concept. Take a movie like Superbad. Two nerdy high school friends trying to get to a party in order to get laid. 80% of the jokes in that movie were built around the need to get to that party so our heroes could get laid. When the concept isn’t clear like that, it isn’t clear what kind of jokes you should write.

And that’s what this felt like. Our two dopey cops had their own brand of comedy going on. Then you had Frankie, who had her thing going on. And the two worlds just never came together.

Bad Cop Bad Cop is also a testament to how important it is to read screenplays. When you don’t read a lot, you don’t know what everyone else is writing. And if you don’t know what other people are writing, you’re likely to write the same things. Because we’re all drawing from the same continuous pop culture news cycle feed, which means that we’re mostly coming up with the same jokes and ideas. UNLESS you read a lot. When you read a lot, you say, “Oh, the last 3 scripts I read used a joke like this. Let’s come up with something else.”

I’ll give you an example. The Kosher Nostra, the comedy I just reviewed in the newsletter, had an Indian bad guy. This script also has an Indian bad guy. Now they’re used differently. And nobody has a monopoly on Indian bad guys. But the point is I read two comedies within one week that had Indian bad guys. When you know what’s out there, you can make a more informed decision. Often you’ll say, let’s dig deeper and find an option nobody else has used.

As for the rest of the script, the plot was shaky. Frankie is friends with the Captain. So it doesn’t make sense that Frankie kidnaps the Captain’s son during this whole ordeal. The son is clearly going to tell his father at the end of this what Frankie did, neutralizing the enormous amount of work she’s put into her plan.

I don’t get obsessed with plot holes in comedies. The genre is pretty forgiving when it comes to plot. But the glare of a plot hole becomes a lot brighter when it’s located smack dab in the center of the story. You’d rather have those plot cracks off to the side.

I believe the writers made a classic mistake. It’s one we talk about all the time. The premise is more complicated than it needs to be. If you kept this as Molly and Devon were supposed to pick up the Captain’s son only for bad guys to kidnap him, and they needed to find the son by the end of the day or they’d lose their jobs and badges forever, then in the process take down a major criminal organization and save the day – that’s all you need. Frankie was funny. But her arrival felt like a different movie. And it fractured a premise that should’ve been crystal clear.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Re-writing common phrases is a great way to come up with a title for your comedy. Turning “Good Cop Bad Cop” into “Bad Cop Bad Cop” was a stroke of genius and was, honestly, the main reason I wanted to read the script. As a fun exercise, I encourage you to rewrite a common phrase to come up with an instantly awesome sounding comedy title. Upvote your favorites! Curious to see who comes up with the best title.

Genre: Sci-Fi Drama?

Premise: (from Black List) An exploration of relationships as a man witnesses different types of love across the ages.

About: This one finished pretty high on last year’s Black List. This is Tom Dean’s breakthrough script.

Writer: Tom Dean

Details: 127 pages

I didn’t make it to Baby Driver this weekend. Maybe I’ll see it tomorrow and do that script-to-screen review for Wednesday. The movie’s doing quite well, which, despite my negative script review, I’m happy about. We need more filmmakers taking chances like Wright.

Speaking of a movie that didn’t take ANY chances, The House was decimated at the box office this weekend. I’m not surprised. It always felt like a lazy idea. Plus, marriage isn’t funny. If you look at the history of comedies, marriage has never been funny.

Then there’s the new Netflix show, GLOW. I don’t know what to make of that one. I’ve watched four episodes and the writing vacillates between really good and really sloppy. The majority of the scenes feel like they were filmed before anyone knew the cameras were rolling. And the main character, played by Alison Brie (the whole reason I tuned in), is inexplicably kept in the background the majority of the time. I haven’t given up on it yet. But episode 5 better be awesome.

Moving on to today’s script, I’m surprised I haven’t reviewed it yet. It’s on the Black List. It’s time-travel. Sounds right up my alley!

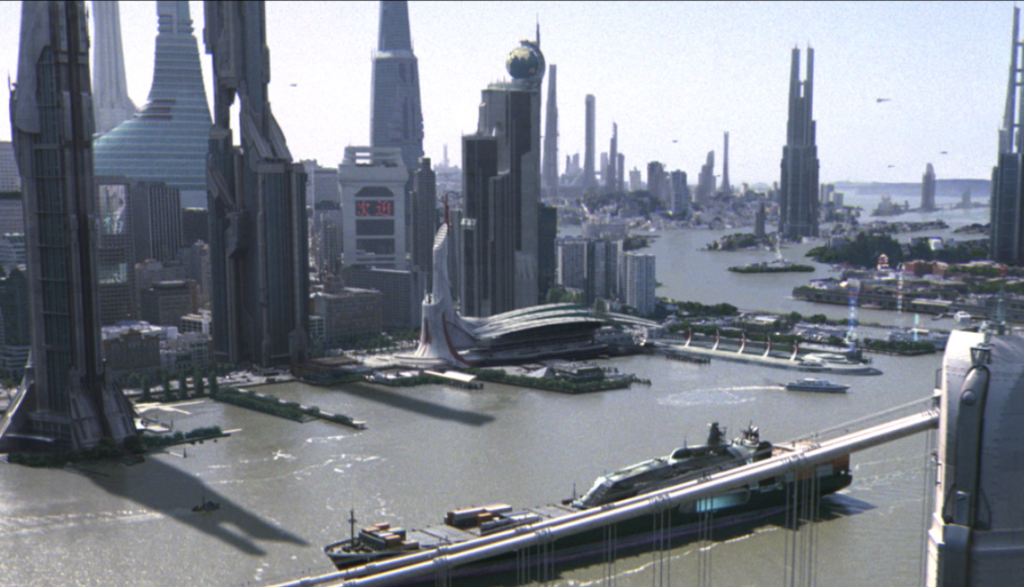

The year is 1960. Sort of. This is 1960 after the invention of time-travel. Which means there’s been some changes. Subtle changes. Like futuristic shit stitched in. But changes nonetheless. It’s here where our Narrator, who will take us through the many time periods in the story, introduces himself. He explains that it’s his job to keep lovers properly meeting each other in all the various time periods.

We first get to know Cecile and Sanjay, who live in Napa Valley circa 1820. But, once again, you have to remember that just because we’re in 1820, doesn’t mean that the characters were born in this era. Both Cecile and Sanjay are from different time periods in the future, or at least, some future after 1820. We watch both of them get in a huge fight, and then we cut to New York City, circa 2402.

It’s here where Sanjay is now a young assistant at a giant company. He’s told by his boss, Henri, to deliver a gift to Henri’s wife back at their condo. Once there, however, a 50 year-old Claire, Henri’s wife, discusses happiness and love with Sanjay before ultimately seducing him.

From there, we cut to Nice, France, circa 1930, where we meet Claire as a 25 year-old. She’s just moved here, and a young cop named Antoine knocks on her door to see if she knows anything about a murder that was committed outside. Antoine falls in love with Claire at first sight, but must use his fellow English-speaking cop to translate his love for Claire.

Cut to 40 years earlier, also in Nice, France, where Antoine is now older, or maybe younger, and is now an actor. Antoine is now in love with Roland, a 30 year-old transgender man. The two fight with each other about their future, specifically how Antoine cannot be with a transgender person.

That takes us to about page 70. And I could go on. But I think you get the idea.

The original paragraph that I was going to write here, I deleted. It was too personal, too negative. And I think Dean deserves credit for his ambition. Without ambition, we get Transformers 6. There’s something to be said for artists who stand up to movies like that.

However, I can’t get past how unnecessarily complicated this story is. There’s the time-travel mythology. There’s a complex narrative. There are tons of rules. There’s no true main character. Dialogue scenes go on forever. The fourth wall is broken. It’s over 120 pages. The characters we do get are all over the place.

For example, one character is a transgender man in one time period, and then a woman when we cut to earlier in his life. Except that he’s actually living in a later time period when he’s younger. It’s almost like the writing is done to specifically confuse us rather than entertain us.

At one point, in 1960, when our characters are going to a movie, they see this on the marquee: “George Clooney in ‘11th Avenue’ Directed by Howard Hawks. His first film after time travel.”

There are also a lot of lines like this: “If it happens you’re familiar with 1820’s Napa Valley, this version won’t look familiar at all. The architecture is limited to the style and technology of early 19th century, but it is very much lived in, developed, and flourishing.”

And then we get dialogue like this: “Okay. Well, when we travel through time, we regulate exactly what dimension it is we travel inside of. That’s why when you travel from 2500 to 1500, you don’t alter the past and create a paradox that would essentially change the course of events so that your parents would never meet and thus never have you and thus never afford you the opportunity to change the past in the first place.”

When you’re reading stuff like this while attempting to follow characters backwards through time, those characters sometimes getting older despite the year being before or getting younger despite the year being after, it gets to a point where you throw up your hands. You’re rooting for scripts that take chances. But if we’re not even sure what’s going on, how can you root?

To the screenplay’s credit, it starts to come together in the end. There was a moment where I thought, “Wow, this reminds me a lot of when I first read Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.” But whereas it was always clear in that screenplay what was going on, this one you’re in the dark the majority of the time.

The thing is, there’s a good idea in here somewhere – this concept of following love stories backwards in time. Going in reverse from each relationship to the characters’ previous relationships, and taking that further and further back until you get to the first person who started the chain. But instead we have this time travel stuff which you need Neil Degrasse Tyson next to you to explain.

So what’s the lesson here? I’m not sure. Shouldn’t new writers be taking chances like this? Isn’t ignorance, in a way, an advantage? Christopher McQuarrie stated that his best script, the one that got him an Oscar, The Usual Suspects, was written with barely any screenwriting knowledge. He said that he wouldn’t have done a lot of the inventive stuff he did had he known then what he knows now.

So why beat Dean up for that? This comes back to one of my weaknesses as an analyst, which is my defiance of experimentation. But I think my issue here is a valid one. Had their been one experimental choice, I would’ve been okay. My problem with La Ronde is that there were half-a-dozen experimental choices stacked on top of each other. And screenplays just aren’t built for that. You can get away with it in novels. Cloud Atlas comes to mind. But screenplays are limited in the types of stories you can tell with them. That’s why this didn’t work for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re going to write long scenes, make sure there’s enough tension to sustain them. If there isn’t, we won’t have enough patience to follow the scene through. So there’s a scene in La Ronde where Sanjay brings a gift to his boss’s wife, Claire. He is supposed to slip the gift in the condo and then leave. It is imperative he not get caught. But the extremely lonely Claire catches him, then asks him to have a drink with her. And they start talking. And then there’s more talking. And then there’s more talking. The talking goes on for a really long time. And because of all that talking that’s going nowhere, the scene loses steam. If you’re going to write long dialogue scenes like this, you need to look for ways to keep the tension. For example, what we could’ve done is had Sanjay’s boss tell him he had to be back within 30 minutes, which is barely enough time to complete the task. Then, when Claire catches him, she tells him, “Don’t worry, I won’t tell on you. If you have a drink with me.” Now Sanjay’s stuck between a rock and a hard place. He has to get back to his boss ASAP. And he has to somehow get Claire to let him leave without ratting on him. Without tension, long dialogue scenes die a sad pitiful death. If you watch any of the master’s long dialogue scenes (Tarantino) you’ll see that all of the best ones are laced with tension. And the few that aren’t, are tension-less.

No review today but not to worry. Any second now, you should be receiving a hot-off-the-presses Scriptshadow Newsletter in your Inbox! Today’s newsletter includes a script review of that spec that fooled Hollywood, some advice on what you should be writing, trivia for half-off a Scriptshadow Consultation and, oh yeah, an UPDATE ON THE SHORT SCRIPT CONTEST.

If you’re on my mailing list and didn’t receive the newsletter, make sure to check your SPAM and PROMOTIONS folders. It should be in there. If you don’t see it there, feel free to e-mail me at Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: “NEWSLETTER” and I’ll send it to you. If you’re not on my mailing list and want on, do the same. Send “NEWSLETTER” to the above e-mail. Enjoy the newsletter, guys. And enjoy the weekend!

A few weeks ago in Amateur Offerings, a Scriptshadow reader brought up that one of the entrants had such a clunky writing style, it was difficult to understand even his most basic sentences. While this is something that happens a lot at the beginner level, you’d be surprised how often I encounter this problem from writers 4, 5, 6 years into their journey.

It’s my belief that these mistakes are made because the writer isn’t aware that their writing is clunky. Usually it’s because that writer isn’t getting enough feedback. But even for the writers putting their work up here, it’s embarassing to tell someone that their writing is at an eighth grade level. It’s easier to focus on some other problem they need to fix. The writer, then, blissfully unaware, continues to write ugly clunky difficult-to-read screenplays.

So today I want to go over the formula for writing a smooth easy-to-read script. Now it’s important to note that the foundation for good writing comes from education. I’m not going to teach you what a noun or a verb is. But even if you aced your AP English class, you still want to keep this formula in mind. Here it is…

Simplicity + Clarity + Voice + Skill = Readability

Let’s go over each of these in detail.

SIMPLICITY

This is the basis for all easy-to-read writing. Keep your sentences simple. The way to do this is to start with a baseline. Whatever you’re trying to say, say it as simply as possible. Don’t phrase your sentence in a weird way. Don’t add a bunch of unnecessary gunk. Give us the action as if you were explaining it to a 3rd grader. So if you want to say that John Wick shoots and kills Frank, write out the most basic version of that sentence as it relates to the scene.

John grabs his gun off the counter and shoots Frank in the head.

This might not be the final sentence you go with. It may need more meat, more punch, more flash. But we’ll get to that. The idea here is to convey what’s happening to the reader as simply as possible. What you don’t want is something like this…

John grabs the jet black gun with authority, piercing Frank between the eyes with a bullet out of hell, who’s dead before he even knows what hit him.

This sentence is technically correct but there’s too much information and it’s a bit of an awkward read. The more words you’re adding, the more commas you’re adding, the more actions you’re adding, the more complex you’re making your sentence. If you keep things simple, you don’t have to worry about clunky sentences. If you want to read a script that embodies this approach, check out Vivien Hasn’t Been Herself Lately, which someone in the comments section should be able to point you towards.

CLARITY

If your writing isn’t clear, forget about us liking your script. We won’t even like your first page. Lack of clarity boils down to three things: poor word choice, awkward phrasing, and the absence of information. The objective of a sentence is to convey to the reader what’s happening. If you’re violating any of these rules, you’re not clearly stating what’s happening. So let’s go back to John shooting Frank. In this version, John’s gun will be in his belt.

John gesticulates his leg to get his gun loose…

This is a classic example of poor word choice. “Gesticulates.” Hmmm… I guess that kind of works? But is it really the best verb to use in this situation? As is the case with all of these examples, I can handle one or two mistakes like this. The issue with clunky writing is that it’s never a couple mistakes. It’s an entire script filled with them.

John gesticulates his leg to get his gun loose and pummels Frank with a bullet.

Here’s where we get to poor phrasing. “…pummels Frank with a bullet.” Once again, I suppose this technically makes sense. But since the average person associates “pummeling” with something other than shooting a man, it forces the reader to stop, reread the sentence, and confirm the action, which is a flow killer. You never want anyone having to reread anything you’ve written. It should be clear the first time around.

Finally, let’s talk about absence of information. This is a HUGE one because many writers (especially beginners) assume that they’re conveying more information than they are. By leaving out the slightest detail or action, a clear sentence can become confusing, or worse, confounding. Let’s say you’re writing a car chase – one of the most famous ever – the semi truck vs. motorbike scene in Terminator 2. Imagine reading a paragraph like this one…

Terminator and John look back at the semi-truck, closing in quickly. He lifts up the shotgun, aiming it squarely at the T-1000 and – BANG! – shoots!

Since you’ve all seen the movie, you know who lifts the shotgun. But imagine if this were at the script stage. A reader would see “He lifts up the shotgun,” and ask, “Who lifts up the shotgun? You’ve listed two people. It could be either one of them.” This mistake is due to absence of information and it happens ALL THE TIME. Make sure you’re reading each of your sentences from the reader’s point of view. Have you included every piece of information necessary to understand the action?

You’re probably saying, “Eh, Carson. Now you’re being picky.” Trust me. I’m not. Cause it’s never just one. Imagine a mistake like this on every page. Coupled with more misused words and more awkward phrasing. A promising script can turn into a 6:30pm drive home on the 405.

VOICE

Voice is the creative side of writing. And, in a way, it works at odds with with our last two elements. That’s because you can’t add creativity without compromising simplicity and clarity. So when it comes to voice, I want you to remember this rule: If it doesn’t make the read more enjoyable, don’t include it. Because that’s the point of voice – to take the words on the page and elevate them to a point where they’re more enjoyable to read.

So what is voice? Voice is the writer’s unique point of view conveyed via a clever phrase, the perfect description, a brilliant metaphor, mastery of vocabulary, an unexpected observation, an important detail, a funny analogy, and the overall style in which they write. Voice does not need to be flashy. It can be subtle. It can be casual. But to make it work, you must be comfortable with your voice. It has to be a natural extension of you. If you force it, the writing will reflect that, not unlike how a nerd looks when he tries to act cool.

Also – and I hope this is obvious – voice should never overwhelm the writing. Content should always be king. Voice is there to supplement the action, not supplant it. A lot of beginners will make this mistake. Let’s go to the master of voice for our next example. This is from Tarantino’s Hateful Eight…

Domergue, whose modus operandi is outrageous behavior and the disarming effect it has on opponents, can’t believe Marquis did what he did. She SCREAMS AT HIM…

When you look at this sentence, you see that it could’ve easily been: “Domergue can’t believe Marquis did what he did. She SCREAMS AT HIM.” But Tarantino loves to tell us about his characters. He loves to add detail wherever he can. So he gave us this minor segue about Domergue before getting back to business. If you were looking to add voice to our now infamous battle between John and Frank, it might read something like this…

John rips his gun off the counter and—

BANG!

Sends a round right between Frank’s eyes, so clean it takes a full three seconds for the blood to flow.

Not going to win an Oscar. But you can see it’s more creative than our original line: “John grabs his gun off the counter and shoots Frank in the head.” Also, note that there’s no end to voice. You can keep going if you want.

John rips his glock off the cheap laminate countertop and—

BANG!

Sends a round express delivery right between Frank’s digits, so clean the blood’s still trying to find its way out.

It’s up to you to decide how far you want to go. If you’re unsure how much is too much, I implore you to err on the side of Rule 1: Simplicity.

SKILL

This is where most writing falls apart. And no, I don’t mean you have to meet a certain skill level to write a good screenplay. But you must know your limitations. The cringiest scripts to read are the ones where the writer is at a level 5 and they’re attempting to write at level 10. Imagine a high school kid trying to write like Cormac McCarthy and you get the idea.

Here’s the good news. You don’t need to be a great writer to tell a great story. But you can ruin a great story by trying to be a great writer. If you’re not a wordsmith, if writing is difficult for you, if sentences read janky whenever you try and get fancy, stick with the first two principles of this formula: Simplicity and Clarity. Remember that the story is the star. If the story is good, you don’t need to dress up the writing too much. I just opened up Terminator 2 and it’s very basic writing. Cameron occasionally gets descriptive but, for the most part, he sticks to simplicity and clarity. So if you can pull those off, and your story’s awesome, you can write a great script.