Today’s review includes one of my favorite little-known storytelling devices. So read on to add a new screenwriting weapon to your arsenal!

Genre: Horror

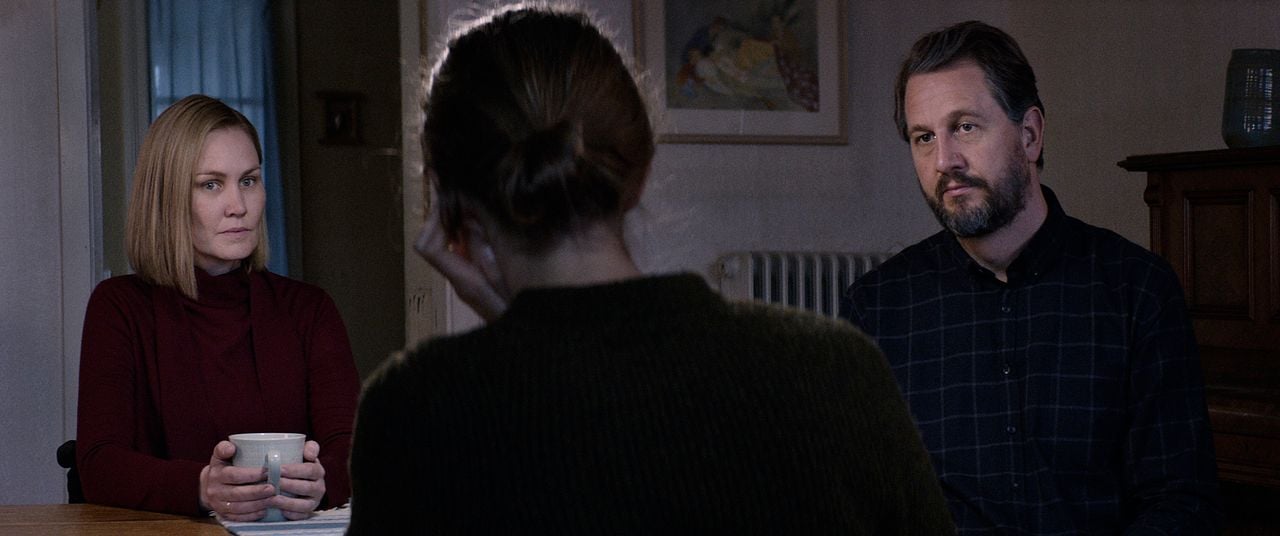

Premise: A young woman with a history of mysterious behavior falls in love with a classmate during her first year at university to devastating results.

About: Take note of this name – Joachim Trier – because I’m laying down money he’ll soon be announced as the director for one of Marvel’s upcoming movies. My guess is it’ll be Black Widow. While the Norwegian filmmaker has been directing movies for over a decade, Thelma is receiving international acclaim, unexpectedly crossing over into all sorts of markets. Trier seems to be enjoying the film’s success with a sense of humor, embracing the “artsy-fartsiness” of Thelma. And so I present to you, the world’s very first lesbian coming-of-age superhero fairy tale.

Writer: Eskil Vogt and Joachim Trier

Details: 116 minutes

Man, this weekend’s box office shows just how difficult it is to survive if you aren’t positioned squarely within one of the big genres. Trying to do something even a little bit different – Den of Thieves and 12 Strong – has resulted in some bloody box office results. It’s also evidence that Hollywood still hasn’t figured out conservative America. 12 Strong was aiming for some of that American Sniper money and got a head shot instead.

Since I wasn’t spending any of my hard-earned money on those options, I decided to take a chance on Thelma, a movie I’d been hearing good things about. And after seeing this clip of the opening scene, I knew I was in. There’s something about those Nordics and their cold creepy perspective on life that I’m ALL FOR. :)

WARNING: SPOILERS FOLLOW

“Thelma” follows the titular character as she goes off to college for her first year. This is a big deal as, up until this point, Thelma’s lived a sheltered life, a life with two extremely religious parents, particularly her father, whose intense calm seems to be hiding an inner rage that could emerge at any moment.

Thelma is ill-equipped to handle the social side of university, so she spends all of her time on her own, until she meets the intriguing androgynous beauty that is Anja. Thelma needs education on even the most basic of social functions, such as friending somebody on Facebook, but once her friendship with Anja ramps up, a whole world of fun follows.

But it turns out all of this social contact is too much for Anja, as she starts having seizures not even doctors can explain. Anja tries to help her through it, and as the two grow closer, Anja takes their friendship into the romantic arena, something Thelma is both drawn to and ashamed of.

She repents as much as possible, asking God for forgiveness, but can’t shake these feelings. It’s around this time, through a series of flashbacks, that we begin to see another side of Thelma, a mysterious dangerous side that hints at the impossible. Thelma, her family fears, has the power to hurt others through thought.

When Thelma and Anja’s relationship goes sexual, Thelma’s had enough, and begs her subconscious to eliminate these feelings. Her subconscious obliges… by erasing Anja from existence. When Thelma goes to their favorite coffee shops, their classes, their hangout spots, Anja is gone. What’s happened to her? Has Thelma really erased her best friend? Or might the answer be tied to her controlling father, who hasn’t told Thelma everything about her childhood?

Place a heavily religious character in a situation where they’re tempted by “sin” and you’re usually going to come up with something good. It gets even better if there’s real danger attached to the sin. This is the secret sauce that drives the middle of Thelma. We’ve set up that the father is a powder keg (the “danger”), then introduced the storyline that could ignite him (the lesbian relationship, the “sin”).

This is a great tip for those of you struggling with seconds acts. Second acts are more about characters dealing with internal and interpersonal conflict than they are pushing the plot forward. So if you establish that your main character must adhere to a certain path, then throw a juicier path in front of them, conflict naturally arises as the character is pulled between the two.

That’s the bulk of what Thelma is. She chooses the sinful path then must battle the conflict within herself to resolve the choice.

There are actually lots of great screenwriting nuggets in Thelma. One of the things Vogt does exceptionally well is build anticipation. Anticipation is one of those things that, if you can master it, you can easily keep a reader glued to your script for 10-15 pages at a time.

For example, in an early conversation between Thelma and Anja, Thelma admits that she tells her father evvveerrrrything. Anja thinks this is a little weird but to Thelma it’s normal. She’s always been close to her parents. In addition to this, we establish how religious Thelma’s father is when Thelma wrestles with whether to tell him she drank a beer. Just the thought of having to admit such a sin brings her to tears.

So when Thelma engages in a lesbian romance: WE KNOW THAT THE TALK WITH HER FATHER IS COMING. This results in… ANTICIPATION. This is a guy who we were afraid of over a beer. We can only imagine what he’s going to say once she admits to having a homosexual relationship. So from the moment the romance commences until Thelma makes that phone call, we’re in anticipatory mode, dreading it.

But let’s get to what I promised you in the header. What’s my favorite unknown storytelling device? Are you ready for this? It’s “Out-of-order flashbacks.” I LOOOOOOVE out-of-order flashbacks! They’re my fave. It’s a wonderful way to fuck with the reader. And Thelma kills it in this area.

We open up the movie with that scene I linked to above. The dad takes 6 year old Thelma hunting. When they see a deer, he raises the gun to shoot it, then, with Thelma standing a bit ahead of him so she can’t see what he’s doing, he slowly points the gun at the head of his daughter. We’re thinking to ourselves – EVVVVILLLL DAD!! I hate this guy!!

However, 30 minutes later after we’re ecstatic that Thelma has finally escaped her father and is at college, we engage in another flashback, also when Thelma is a little girl. Except in this flashback, which takes place before that day, the family has a newborn baby boy. Uh-oh. There ain’t no newborn in the present. What happened to him? As the newborn cries away in its crib, becoming more and more irritating, Thelma closes her eyes, thinks real hard, and the baby is… gone. The parents come in, confused. Where’s the baby? It’s only after looking around that we find him under the couch.

All of a sudden, we’re not so sure the dad is the problem here. Maybe Thelma is the problem and the dad was right to consider killing her. This is why playing with out-of-order flashbacks is so fun. You can change the entire lens from which your audience sees your characters in an instant, forcing them to revisit every scene from a new perspective.

Keep in mind that you don’t have to limit the flashbacks to two. You can continue to use out-of-order flashbacks throughout the script. Maybe, for example, on the third flashback, you switch things around to make it look like Thelma is the good guy again. Then in the fourth, Thelma’s bad again. You can keep the audience guessing all the way til the end.

Even beyond the screenwriting, this is a great movie. The direction is awesome. Lots of wide beautifully composed shots. The acting is incredible. The main girl is amazing. The casting is great. There isn’t a weak link in the film. That dad, man. Whoa. It’s dark. So if you’re not in the mood for that kind of film, don’t watch it. But if you’re up for a great creepy atmospheric movie with shades of It Follows and Let The Right One In, Thelma needs to be your next film.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This script reminded me that, when done well, a character with strong religious ties being tempted by “sin” is one of the more compelling inner conflict battles a character can go through.

What I learned (turbo-charged): Take note that you have two options as to how to present sin. You can present sin in the context of what’s objectively wrong. And you can present sin in the context of what’s subjectively wrong. The latter plays better onscreen. For example, if a religious person is tempted by drugs, everyone agrees drugs are bad. So the character dealing with that is a bit on the nose. But if a religious person is tempted by homosexuality, as is the case here, many people don’t see that as a sin, and therefore view the hero as a victim of their own religion. Because of this, they connect with and root for the character more, which was the case with Thelma.

Genre: Gothic Drama

Premise: A psychiatrist becomes involved with a disturbed young woman, but falls foul of those responsible for her condition — a former Nazi doctor and mysterious Reverend Sister.

Why You Should Read: Played against the rainy altitude of the Austrian Tyrol in 1975, FROM THE CONVALESCENCE OF CHRISTIANNE ZELMAN is both love story and Nazi fairy-tale. The role of Christianne is tailor-made for an Oscar-bound actress while the script itself resurrects an all but forgotten genre — one that allowed me to showcase character and dialogue inside a heightened storyworld. Indeed, I tried to write something that owes as much to golden-age melodrama as it does to the likes of Tennessee Williams and Rainer Fassbinder. In short, I’m convinced this script is like nothing else around at the moment!

Writer: Levres de Sang

Details: 99 pages

What I admire about Levres is that he seems to understand he’s pushing a story that’s not the most accessible. He knows this isn’t straight horror and that Blumhouse isn’t about to come knocking on his door after reading it. But my question to Levres would then be, what is the goal here? If you write something that’s far outside a noted genre, what can you expect other than for it to be an interesting experiment? I say this because I think Convalescence has the bones of what could be a movie if it was written as a horror-style thriller. I don’t know if Levres is interested in exploring that route, though.

Let’s get to the plot. And I apologize in advance for the vagueness of some of the story beats as I wasn’t always clear what was going on, something I’ll be talking about in the analysis.

It’s 1975. Austria. Dr. Michael Reinhardt, a married psychiatrist, is being called away to evaluate Christianne Zelman, a young woman of 29 recovering from an illness. Reinhardt, I think, is being given the order to classify Christianne as insane so she can be institutionalized.

So Michael travels to Christianne’s home where her mother, Luise, is taking care of her. Christianne also has a young son, Emil. And every night the family goes through an elaborate routine whereby Luise makes warm milk and has Emil takes it to her mother.

Christianne’s a weirdo. She keeps a dressed-up mannequin next to her bedside and will occasionally take on the personality of another woman. When Michael shows up, Christianne isn’t quiet about the fact that she loves him immediately. Michael, despite knowing his patient is unwell, can’t deny he’s intrigued by her too.

The story seems to center on Christianne recounting her past institutionalization, where she was a patient for a mysterious doctor named Rupert Oberweis. It’s through her recounting of this past that we learn a lot of interesting things, such as the fact that Christianne was born on the exact same day Hitler died. And that she was part of a drug program that got everyone in the institution addicted except for her.

As Christianne falls more in love with Michael, he will have to sort through his own growing feelings to figure out what happened to Christianne in that facility and why it is that everyone seems so nervous by Christianne taking a liking to him.

Let’s start with the writing here because I had a tough time with it. There is a pervasive fuzziness, both in the way characters were introduced and the way plot points were unveiled that often left me unsure of exactly what was going on.

My guess is that this is a component of the genre Levres is shooting for? I noticed Levres and a few others in the comments talking about this as a some form of 70s dream sub-genre? Which would mean the fuzziness is deliberate? Which is cool if that’s the way the genre works. But I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t frustrating to sort through.

I mean we can start right at the title. I didn’t know what “Convalescence” meant. It’s not a word that has come up in any conversation or reading of mine for the past 30 years. And I believe it’s the writer’s job not to assume that any non-basic word is a given. It’d be nice if a character explained what was going on with Christianne without using that word.

I suppose this leads to a deeper line of questioning in regards to the expectations Levres sets for this story, namely, “If you don’t know what convalescence means, you’re not my audience anyway.” And is that approach invoked throughout the screenplay, where it’s kind of like, “If you can’t keep up, sorry not sorry.”

But I had real problems sorting out what was going on because SO MUCH was fuzzy. I’ll give you an example. About midway through the script, the characters find three dead women who were creepily embalmed. I don’t know any situation by which you find three young women dead and embalmed where there aren’t 30 policeman swarming the place within an hour and the media swooping in going crazy. But for the characters in Convalescence it was like, “Whoa, that’s weird,” and they just keep going on like it was no big deal.

That kind of thing would happen a lot where you’d say, “Wait a minute. Why are people acting this way?” Or “Why is this happening?” “Why isn’t that happening?” And I was never entirely sure. At a certain point, around page 70, I lost the will to search for logic. I figured if I couldn’t take anything at face value, what was the point in trying to make sense of things?

Again, I don’t know if this is a specific sub-genre where this kind of thing is encouraged. If it is, then I’m not the audience. But if we’re judging this strictly as a screenplay, I would’ve liked for everything to be clearer. I would’ve liked to know exactly who each character was when they were introduced. When plot points were hit, I would’ve liked for them to be hit hard and clear. For example, another WW2 film, Indiana Jones. Two guys sat Indiana down and said, “This is what you need to do, and this is why you need to do it.” And they went into extreme detail. This may seem like pandering to some. But this is the setup for your entire movie. You want your audience crystal clear on what the hero’s goal is.

I never truly knew what Michael was there for. I think he was there to diagnose Christianne to possibly re-institutionalize her? But I was never clear on why that needed to be done. I also wasn’t clear on what this previous institution Christianne was a part of was. What she was doing there. No character ever explained it satisfactorily (or clearly). And this added to the pervasive fuzziness of, basically, every plot point and character in the story.

I don’t know. It’s frustrating because I like a lot of the elements here. Mysterious woman. A past filled with secrets. Top secret medical experiments. Nazis. Hitler. All of that stuff is right up my alley. I SHOULD be the audience for this. And yet all of those plot points were buried inside of developments I only partially understood.

I would like to see Levres attempt to tell a more traditional horror story with more traditional horror beats. Even this one, but stripped away of all the wishy-washy elements and with all the plot points hit hard.

1) Michael’s bosses are mysteriously strong-arming him: We need you to go classify that this girl is insane, whether she is or not.

2) Meet the girl. She’s weird and intriguing. Something terrible happened to her. Michael wants to know what.

3) There are hints that she may have been involved in Nazi experiments.

4) There are hints that she may even be tied to Hitler himself.

5) The residents of the small town start to strong-arm Michael when Christianne reveals too much.

6) Michael is in danger. He has to get out alive. But he’s resigned to find out the truth first.

What’s wrong with a simple horror story like that? You’ve got the atmospheric writing down. You just need to write more clearly – clarifying characters and motivations and major plot points. There’s a fogginess to the writing and this story that’s obstructing what could be really cool. Then again, maybe that’s not what Levres is interested in.

Script link (updated version): From the Convalescence of Christianne Zelman

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s a big misconception out there that you should be writing for yourself. Make yourself happy and you’ll write something great. Of course you should be writing stuff that interests you, but never forget that you’re writing for the reader. You’re writing to give them an entertaining experience. I think Levres was focused more on writing for himself here, and that got in the way of creating something a reader could engage in.

One of the things that separates professional writers from amateurs is character work. Their characters are deeper, more compelling, and overall more memorable. Unfortunately, it’s difficult for the amateur writer to understand WHY their characters lack these qualities. All they hear is, “The characters lacked depth,” or “The characters weren’t three-dimensional.” What the hell does that mean? How do I fix it? Even if you asked the person who gave you the note, they probably wouldn’t know. Creating rich compelling characters is the hardest thing to do in writing.

Luckily, you’re talking to the guy who’s read every script on the planet. And if there’s one thing I’ve discovered, it’s that when a character goes bad, it’s because the writer doesn’t understand the basics of character creation. They may have added a flaw, some inner conflict, a vice, and yet they keep getting the note that the characters don’t work. The writer points to his script: “But look! The proof is right there! I’ve added all the things I’m supposed to add. You’re wrong!” Sorry, just because you have bread, beef, and thousand island in your fridge doesn’t mean you know how to make a Big Mac.

I’m not going to give you ALL the ingredients to creating a great character. There’s too much. An extensive backstory. Approaching the character truthfully. Creating the kind of person who says interesting things and talks in an interesting way (which leads to good dialogue). And yes, strong flaws, some inner conflict, and a well-explored vice help as well. All of that takes years to master. But what I can give you is the base from which to start. If you can get that base right, all of the other stuff will come. How do you find this base? You ask a simple question: What’s their thing?

A character’s “thing” is the component that defines them within the construct of the story. Strip away the bullshit. Get to the core. What is the thing that defines them? Bobby Riggs’ “thing” in Battle of the Sexes is that he can’t handle being out of the spotlight. He’ll do anything to stay in the public eye. Liam Neeson’s “thing” in Taken is that he wants to make up for all the lost time with his daughter and is willing to do anything to get back in her life. Tommy Wiseau’s “thing” in The Disaster Artist is that he just wants a friend.

If you understand that beyond the bullshit, all that confusing flaw/conflict/vice shit, that a character is just looking for a friend, it becomes so much easier to write the screenplay because the majority of the scenes will involve challenging this premise. An example from The Disaster Artist would be when Tommy comes home after a long day and finds Greg in their apartment with his girlfriend, watching a movie. You can see the jealousy dripping off Tommy’s brow, and while he pretends to be okay with everything, there’s a sting to his words, a fear of betrayal. This man’s thing is that he just wants a friend. Here he is potentially about to lose one to this girl. That’s what makes a good movie scene.

If you don’t know your character’s thing, you can’t write a scene like this. I’ll give you an example, and it’s from my least favorite movie of last year, Beatriz at Dinner. The movie was about a poor masseuse/healer who gets stuck at her rich client’s home during an important dinner. The writer tried to get too cute and give the character too much going on. As a result, we had no idea who she was. And the choices that the story made were, predictably, directionless as well. At first Beatriz was a voice for the poor and overlooked. But then they introduced this thing about her loving animals and being upset that animals were being abused (what the fuck???). And then she becomes suicidal, which contradicted everything that had been set up about her. The character was a complete mess and it’s because they tried to do too much. They should’ve asked, “What’s her thing?” and stuck with that thing!

This is a huge problem with screenwriting in general is that writers think they have to get too complex. The solution is almost ALWAYS to simplify, not complexify.

To help you further understand this tool, here are 15 characters and their “thing.” A couple of points I want you to notice. First, take note of how SIMPLE they are. And second, remember how the majority of the scenes in the movie put that thing to the test. So with Mikey in Swingers, every scene either mentions Mikey’s ex or, if it doesn’t, deals with it indirectly. Mikey losing at blackjack is only made worse by the fact that he has no one to emotionally support him anymore. Okay, let’s take a look…

Peter Parker – Wants to save the world despite the fact that he’s not ready.

Mikey (Swingers) – He can’t get over his ex-girlfriend.

Jordan Belforte (The Wolf of Wall Street) – Craves excess. Always wants more.

Deadpool – Wants revenge.

Rick Blaine (Casablanca) – Doesn’t stick his neck out for nobody.

Luke Skywalker (Star Wars) – He dreams of making a difference and going off to do bigger better things.

Ferris Bueller – Just wants to have fun now, embrace the moment.

Furiosa (Fury Road) – Get these women to safety.

Harry (When Harry Met Sally) – Doesn’t believe men and women can be friends.

Officer Hopps (Zootopia) – Prove that anybody can do anything if they put their mind to it.

Mila Kunis (Bad Moms) – Sick of being perfect.

Robert Pattinson (Good time) – Will do anything for his brother.

Anne Hathaway (Colossal) – Can’t get her shit together.

Matt Damon (The Martian) – Methodically solve each and every problem one at a time.

Tommy (Dunkirk) – Survive by any means possible.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. I highly recommend not writing a script unless it gets a 7 or above. All logline consultations come with an 8 hour turnaround. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Genre: Biopic

Premise: (from Black List) The story of writer/director John Hughes, whose emotionally honest high school movies helped to define American culture in the 1980s–but who, at the very height of his success, abruptly abandoned filmmaking for reasons that have never been fully explained.

About: It’s back to the most recent Black List with today’s script, Hughes, written by Andrew Rothschild. Rothschild has been working his way up the ladder, writing a lot of short films and most recently developed the series “Zac and Mia,” about two cancer patient who fall for one another that streams on Verizon’s streaming service, Go90. Hughes received 13 votes on the 2017 Black List.

Writer: Andrew Rothschild

Details: 119 pages

Today’s script is about John Hughes, the legendary 80s writer-director who disappeared from Hollywood without so much as a goodbye note. How big of a deal was Hughes? I’ll let the title card at the opening of the script tell you…

“In the 1980s, John Hughes wrote, produced, and/or directed nine films, including Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club, Pretty in Pink, and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Together, those films comprise one of the most successful single-decade bodies of work in cinema history.”

As tired as I am of writer biopics, I’ll never tire of John Hughes. I think his story is fascinating. I love how he built his screenwriting model on advertising. Obscenely simple premises that are easy to market. I love how he moved teen flicks out of the ridiculous (Porky’s) and into reality. I loved how much fun he had with dialogue. And I’m as curious as anyone why he threw it all away. Or ran away.

Today’s script attempts to answer that question and does so controversially. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill writer biopic. It’s at times surprising, weird, even uncomfortable. However you want to categorize it, it’s different. And “different” is a dying art when it comes to this genre.

It’s 2001 and John Hughes is being interviewed by Elliot Gibbs, an eccentric Southerner who’s doing a profile in Premiere magazine on John’s son’s first film. Hughes thinks this will be a fluff interview where he can shower his son with compliments. But Gibbs has an ulterior motive. He wants to know why Hughes left Hollywood.

Hughes catches on quickly and tells Gibbs to leave. But Gibbs drops a bomb on him. He’s doing an unauthorized biography on Hughes. He threatens Hughes to either tell his story or let it be told for him. Hughes threatens to sue for slander but learns Gibbs has a legit shadow source. Hughes sets out to find who that source is.

We hop back in time to when John was 16 in the 60s and when he fell in love with a popular red-headed girl named Tiffany. Unfortunately, John was a geek, so while the two experienced a couple of great nights together, she eventually moved back to her own kind, leaving John broken.

Flashforward a couple of decades and John is a hot writer who wants to make his first movie, Sixteen Candles. One of the first things we learn about John is that he was intensely difficult to work with. The studio wanted to cast a star in the lead role. But John wanted a nobody actress who he’d never even seen act (he’d only seen her headshot). That actress was a teenaged Molly Ringwald. We see Molly come in to audition only for John to hand her the role to not just that movie, but “the next five movies” John was doing. A confused Molly agrees, but even at that young age knows something is off. Who gives five movies to an actress he’s never seen act??

Turns out John was less interested in making movies than he was hanging out with his actors and having fun. His sets were long drawn out improv sessions filled with goofs and gaffs. In addition to this, John was drawn to Molly. And the crux of Gibbs’ book seems to imply that there was more that meets the eye when it came to their relationship. Once John realizes that it’s this salacious story Gibbs is after, he curses him out, claiming none of it is true. But that’s not what Gibbs’s source says.

Which leads us to our third act, where John finally figures out who’s been feeding Gibbs this information. It is a stunning betrayal, but not an unexpected one. The revelation forces John to face his biggest flaw, the fact that he never wanted to grow up, and that once Hollywood made him, there was no reason left to stay.

Whenever you write a biopic that starts in the present day, you need to identify a framing device. A framing device is the story that sends you back into the past to tell your protagonists’s story. One of the most popular framing devices occurs in The Princess Bride, where to get to the story, a grandfather must read his grandson a book.

Most writers don’t think the framing device is important. But I think the more clever the framing device, the more horsepower your story will have. And this one is clever. A mysterious source close to our hero is selling secrets and Hughes has to figure out who it is. This had me just as interested in the present-day storyline as Hughes’ past. And that’s the way you want it. If all your framing device is doing is providing exposition, those sections will be snore chores.

As for the rest of this script, I don’t know what to make of it. I’m glad it didn’t go the way I expected it to (Ferris Bueller isn’t riding shotgun with Old John Hughes wherever he goes, giving him life advice). But it’s a bit of a “be careful what you wish for” scenario. I got my darkness. I got to peak under the hood of Cameron’s Ferrari 250 GT SWB California Spider. But maybe I didn’t like what I saw.

The story uses John Hughes’ obsession with Molly Ringwald to drive home his Peter Pan syndrome. His movie productions were basically an opportunity to experience all the fun he never got to experience in high school. The relationship between Hughes and Ringwald gets uncomfortable at times. The script always walks a tightrope with it, never committing to the idea that anything happened, but regularly implying it could have. And while that implication made for some solid dramatic conflict within the movie-making sequences, there was this innate feeling that you wished it wasn’t there.

Also, the pervasive thought with John Hughes leaving Hollywood is that Hollywood was too tough for him. That it beat him up and spit him out. But “Hughes” flips that idea on its head and says that maybe it was the other way around. According to Rothschild, Hughes could be a tyrant, taking advantage of his power to play by his own set of rules. It wasn’t uncommon for him to do 50 takes, carelessly burning studio money, simply because he was having fun hanging out with his actors. And we all know that once those number 1 box office weekends stop, studios are a lot less tolerant of that behavior.

Look, I don’t know how much of this is true. The script starts out by saying, “What follows is speculation.” So I’m not going to treat it as gospel. But from a storytelling point-of-view, this unexpected take on a Hollywood legend kept me interested.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I still think the John Hughes model can work in 2018. Find a high school concept and create a very simple container for it. With The Breakfast Club, it was one day in detention. With Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, it was one day ditching school. There’s something about a tight time frame coupled with the unique potency of being a teenager that will always work as long as you don’t screw it up. Man, this is making me want to go write one of these scripts right now!

Genre: Cop Drama

Premise: Two rookie Chicago cops find themselves embroiled in a multi-gang heroin war.

About: This script finished in the middle of the pack on the 2009 Black List. The writer, Justin Britt-Gibson, has written on some high profile shows, including “The Strain,” “Banshee,” and “Into the Badlands.”

Writer: Justin Britt-Gibson

Details: 110 pages

If you take anything from today’s review, let it be ELEVATION.

More than EVER you need to elevate your ideas. You’re no longer competing with E.T. and The Mask. You’re competing with superhero movies that all have 200-300 million dollar budgets. So if you’re not elevating your ideas to bring something new to the table, you’re going to get swallowed up.

Don’t write a drama about the difficulties of a two-race relationship. Write Get Out.

Stay too close to the template of a genre and I’m telling you, you’re toast. You have to add something more.

William Finley is a fresh-faced African-American cop on the Chicago police force, and on his first day of duty, he’s teamed up with fellow rookie James McCoy, an alcoholic dick who’s been sent here by his rich father as punishment for being such a fuck up in life. The two are tasked with escorting a medium-level thug named “Q” across town.

Meanwhile, a wild card crime boss named Hanson steals millions of dollars worth of heroin from former kingpin Frank Russo. I say “former” because Hanson kills him. Hanson then pulls a Joker, recruiting all the big gangs in Chicago, and tells them that he’s now the top drug dealer and all of them have to buy from him.

Finley and McCoy are so incompetent, Q escapes, which means they have to go looking for him. They eventually find him dead, shot execution style, and tab Raymond Priest, Nu Country Gang Leader and just released from prison, as the likely killer. So the guys go looking for Priest, who turns out to be connected to Hanson.

But that’s when the cops discover the capper. Hanson is connected to the cops. Which means it’s the CHICAGO PD who really took that heroin and are selling it. Poor Chicago. Can’t seem to shed that corruption label ever since Capone. Anyway, once Finley and McCoy know the truth, they’re targeted by their own, and must not only survive, but figure out a way to take out the snake inside the organization they work for.

The reason I read Streets on Fire was because it was set in Chicago and I thought it’d be fun to read something about where I’m from. Fail.

Here’s the thing, guys. If you’re going to write in a 100 year old genre – Cops and Robbers – you better think long and hard about how you’re going to bring something new to that world. And if you can’t? Don’t write it. Because nobody wants to read a generic cops chasing bad guys movie.

One of the only ways you can still write in this genre is to world-build. Treat your cop movie like Star Wars. Or Harry Potter. I don’t mean make it a fantasy. I mean wherever it’s set, build that world up so that we FEEEEEEL the mythology of this place you’re telling us about. The Godfather is a great example. There’s no other movie in history that gave me a better feel for the Italian mafia than The Godfather. Sicario is a solid example, too. That one didn’t get AS MUCH into the mythology of border patrol as Godfather did the mafia. But it did enough so that I felt like I was in a unique world learning new things.

I grew up in Chicago. And there wasn’t anything in here that reminded me of the city. The fast food. The crazy weather. The racism between white cops and the black populace. How every single street is filled with potholes. How much the town loves its sports. In other words, this could’ve been set anywhere. And once that happens, you’re writing a generic cop drama. And this isn’t 1983 anymore. Those don’t sell. You need to give us more.

And, to be honest, mythology and world-building should be your last option. You should be looking to elevate the genre in some way. Or go with more of a high-concept hook, like Safe House or The Equalizer. You can also get way with cop period pieces, which gives the genre an, ironically, fresh feel.

After I finished this, I thought to myself, why would anyone write this? Even in 2009, this genre was dead. And then the genius of this spec hit me. This is the PERFECT spec to write if you want to work in TV. The majority of TV is built around the procedural format. So if you can write a good cop flick, you’ll be in high-demand on the TV market. And that’s exactly what happened with Britt-Gibson. He’s worked steadily on some high-profile TV shows.

And maybe that’s the big lesson for today. Selling a script is hard in these times. So play the long game. Make your script a resume for whatever you want to write in. Whether it’s television or a certain movie genre, whatever. If you can execute an idea well, you can get work writing similar ideas.

But yeah, this kind of thing is so not for me. It actually pains me when I have to read stuff that’s this generic. It’s writing, guys! Your job is to ELEVATE! Give us something bigger than the norm.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whatever qualities you give your characters, you have to then figure out WHY they have these qualities. You can’t just make a character an asshole “because.” McCoy is the best thing about this script. He’s the character who sticks out the most. Also, he’s entitled and a dick. So you have to explain, at some point in the movie, WHY he’s entitled and a dick. Britt-Gibson eventually reveals that McCoy’s dad always bailed him out of trouble, he was a star athlete, he’s lived a charmed life, never had any responsibility. Of course he’s a dick. When you do that extra work, your character feels MORE TRUTHFUL because his behaviors are based on a real past as opposed to a couple of adjectives.