Genre: Superhero

Premise: When a man goes rock climbing with his friend, he’s abducted by aliens and inexplicably turned into a giant rock creature.

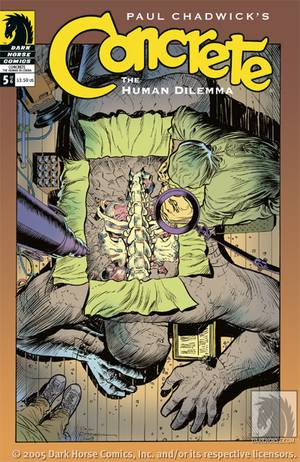

About: Concrete was a cult comic book in the late 1980s, birthed out of the Dark Horse comic book label. The creator, Paul Chadwick, has worked in comics forever and, in 2005, became a key creative force behind The Matrix Online, a multiplayer game set up by the Wachowskis to continue the Matrix storyline. I knew nothing about this comic but became interested when I looked at the comic’s art, which has a haunting quality to it.

Writer: Paul Chadwick (writer of the screenplay and creator of the comic)

Details: 107 pages (undated – but somewhere in the 1990s)

I have an intriguing question for you. How would you rank individual superhero properties at this moment? Batman used to have a stranglehold on the top position. But I don’t think he does anymore after these DC disasterfest flicks. You could argue that Batman might not even be in the Top 5 anymore. Deadpool. Wonder Woman. Iron Man. Spider-Man. Captain America. Who do you think owns the sandbox?

The question has me wondering what makes a comic book movie stand out these days. There are SO MANY that simply having a dude with a gruff voice and a bat-mask isn’t enough anymore. Either you have to find a comic that explores the genre in a unique way (Deadpool) or, if you already have an established property, you have to find a director who’s going to add a stylistic flourish that gives that property a fresh feel (Thor: Ragnarok).

The Concrete art has me hoping we’ll get a little of both here. Let’s take a look.

I know a script is in trouble when the writer doesn’t make clear what the main character’s job is. When we meet Ronald Lithgow, he’s in a senator’s office writing down notes as the Senator speaks. Does this make him his assistant? A co-worker? Someone who works alongside the Senator and is merely keeping notes for himself? We’re not given a clear answer, and this becomes an issue throughout the script.

And, actually, it’s a problem a lot of new screenwriters have. It’s not that they don’t tell you what the main character’s job is. It’s that unclear details become a pattern throughout the script, leaving the screenplay feeling like you’re squinting at it through a set of foggy glasses.

Anyway, so Ron goes on a vacation with his good buddy, Michael, to do some hardcore rock-climbing. However, when their curiosity gets the best of them and they explore a cave, they find some terrifying rock creature aliens waiting for them, who knock Ron and Michael out, and then when they wake up, they’re in an alien rock cave lab, having been turned into giant rock creatures themselves.

Michael is killed – RIP Michael – but Ron escapes, and when a local town reports a Sasquatch-like creature hopping around the premises, the NSA swoops in, and an evil dick named Joe Stamberg, brings Ron to an NSA lab so he can study him. It’s there where Ron meets the beautiful Maureen, a scientist who has a jonezing for rock men. Ron seems perfectly fine with being treated like a guinea pig for some reason, but breaks out when it’s revealed that Maureen has been removed from the project.

Once out and spotted, Ron becomes an instant celebrity, and that’s when Stamberg realizes he can make some money off this thing. So he pulls a George Lucas and and sells Concrete’s rights to comic book and toy companies everywhere. Concrete starts making appearances on news shows. Everyyyyyybody loves Concrete.

But Stamberg wants to take things further, and when there’s an incident at a mine where dozens of miners are trapped, he sends Concrete there to save them. Pump up his celebrity even more. But Concrete screws up the dig and, as a result, men die. Is the Concrete love now over? Will the world turn against him? And if so, what else is there left for a man trapped in a 12 foot tall body made of rock?

Right, so, I’m not going to mince words. This was a mess. I’m guessing that while Chadwick was an accomplished comic book writer, this was an early foray into screenwriting. There were too many Screenwriting 101 problems.

For starters, the celebrity sequence – where Concrete becomes a worldwide celebrity – it lasts 30 pages! I mean, I can see a 7 page montage TOPS. But it just went on and on and on. And this isn’t what screenplays are made for, giant 30 page sections with good vibes and zero conflict. You can’t be that friendly for that long without the audience getting bored. This comes down to a basic understanding of how screenplays are paced. It’s okay for good things to happen for a scene or two. Maybe even three. But then you got to start throwing conflict at the main character.

And that was another problem. Ron had zero issues with being imprisoned by the NSA. His attitude was, “Yeah, whatever you need.” And since that section ALSO went on for a long time, that was another area that got boring.

Then there was Ron himself. For such a cool looking character, there’s nothing going on with him. One of the things you need to do early on in a script is establish who your main character is BEFORE THE TERRIBLE THING BEFALLS HIM. If we don’t know who he is, then what happens to him feels empty.

I’ll give you an example. If we’d been shown, early on, that Ron was always getting overlooked, that he wanted more attention, that he was invisible at work, NOW when he becomes this huge celebrity, it has more weight. Because it’s tied to something that we’ve established he wanted. Then you can go into a “be careful what you wish for” story.

And I’m not saying you had to go that route. I’m saying you had to go SOME route. And this script gave us no route early on. By not establishing who the hero was… EVER… we never knew what the main character’s journey was supposed to be.

The problems don’t stop there. Concrete doesn’t encounter his first opportunity at heroism – saving people in the mine – until page 80!!! This is a superhero movie. The first big heroic act should not be occurring 80 pages into the story. Sure, if this is a more cerebral character-based superhero movie, I’d understand the lack of big set pieces. But we just established there’s nothing going on with this character. I don’t have any idea what I’m supposed to be thinking about him. As far as I can tell, he’s a guy who’s relatively happy to have been turned into a giant rock man. Which is a leap you have to explain to the reader. But we never get any explanation.

To be fair, an entire superhero renaissance occurred between the time this script was written and today. The bar has been raised considerably. If they’re going to still develop this project, I would go 100% away from the celebrity stuff and focus more on the turmoil of what it’s like for this man to live like this. Those are the most arresting images from the comics and the far more interesting theme. This long drawn out rise to fame is the last thing that’s going to interest people about a rock dude.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whatever big themes you’re exploring in your movie, you have to build a bridge between those themes and your character. There’s no reason to make celebrity a giant theme in your story if your main character doesn’t have opinions or conflict about celebrity. A big component of Iron Man, for example, is his ego. So when he makes the decision to tell the world he’s Iron Man and become this celebrity, that decision is tied to his character in a clear way.

No Amateur Offerings this weekend, guys and gals. I’m going to review Levres 2nd Place script next Friday. If you want to be included in NEXT WEEK’S batch of Amateur Offerings and compete for that review on the site, send me a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and why you think people should read it (your chance to really pitch your story). All submissions should be sent to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com.

In the meantime, use this thread to keep yourselves accountable for the year. Remember, you should be shooting for 15-30 hours of writing a week depending on how busy your schedule is. The idea here is to be truthful about the amount of work you’re putting in. Also, be supportive and encouraging to others. Writing is a lonely endeavor and it’s nice to know people are there for you. Basically, these accountability posts are meant as big buckets of motivation. If you guys continue to find these posts helpful, I’ll keep posting them. Happy writing!

Genre: Mystery

Premise: (from writer) The host of a popular skeptic/debunking radio show works alongside a reluctant psychic in a last ditch attempt to find his missing daughter.

Why You Should Read: I was ecstatic when I found out an earlier draft of this script placed top 10 in the 2017 Launch Pad Feature Competition. From there, the contest organizer sent the script to a producer looking for material and after the producer read it, he sent it to a manager he knew. The manager got back to him within 24 hours to say he loved the story as well and wanted to meet me. Momentum, momentum, momentum! I owe that manager and producer a ton of credit, because together we shaped the story into a project we felt the industry would consider. — My manager had a plan to keep the reads exclusive, targeting select production companies, so why am I making the script public, submitting to AOW in hopes of getting a review? After the screenplay was sent up to the owner of a fairly well known production company and interest expressed, my manager vanished. This was in late July and to this day I have no idea what happened, I hope it wasn’t something catastrophic. In the meantime, it’s back to square one for me and I’m proceeding as though I’m unrepresented. I’d love to know what the Scriptshadow community thinks of the story – and more importantly – if they’d pay to see the actual film. Also, I can’t lie… having struck out in two previous AF attempts, the competitor in me seeks to earn that elusive “worth a read” my first ever submission – The Telemarketer – failed to produce.

Writer: Jai Brandon

Details: 119 pages

We have a variety of formulas that result in success in the movie business. Superheroes. Underdogs. Biopics. Monster-in-a-box. In the novel world, there’s one. MISSING GIRL! Hell, even if all you do is include the word “girl” in your title, you’ll sell 10,000 copies. And, for the most part, when this formula is transferred into the movie world, it works as well.

Gone Girl. The Girl on the Train. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

It makes perfect sense when you think about it. We are hard-wired to worry about helpless people placed in dangerous situations. And after we hear about one of these scenarios, we don’t feel at peace until we find out that the missing girl is okay. Even if it’s just a made up story!

There is a significant trick involved in getting these stories right, though. And I’m going to share that with you…. after the synopsis.

40-something Chace Clay is popular radio host at a local news station. But while he’s got his professional career on point, his personal life is a mess. He’s got an ex-wife, Lori, he’s always bickering with. He’s got a current girlfriend, Reesa, who’s a tinder box ready to explode. Luckily he has his beautiful little girl, Emily, to add some balance to his existence.

However, that balance is rocked when Chace’s babysitter loses Emily. Chace races home and soon cops are swarming the premises, trying to figure out how a young girl can just disappear. When they can’t find her, the community sets up a search in the local woods, and it’s there where Chase meets the mysterious Amari, a local African-American janitor with a psychic gift. Now’s the time I should tell you that Chace hates psychics. In fact, he lost his entire childhood with his brother when a psychic convinced their family that his missing brother was dead. 15 years later, the adult brother showed up at their door. It turns out a local creep had kept him locked in his basement for a decade. So, yeah. It’s safe to say that Chace doesn’t trust this guy.

However, it’s not like Chase has any leads. All the people closest to him passed their polygraph test. So he needs to think outside the box. Amari joins Chace, who suspects another psychic may be involved that he recently humiliated on his show. Chace thinks she may want revenge. The lead does bring them to the woman’s adult daughter, who claims she saw Emily earlier in the day.

This sends Chace and Amari on a deep dive into everyone Chace knows. But when the investigation turns around and points the finger at his current girlfriend, Reesa, everything gets thrown out the window. At a certain point he realizes he’s too close to judge anything objectively, which means he’ll have to lean on the one person he trusts the least, Amari.

We’re going to start at the beginning here. And I send this advice out with love, of course. I know how hard Jai works and I know how long he’s been at this. A title page in a unique font tends to be a red flag. NOT ALWAYS. But seasoned Hollywood readers will treat it as such. Also, 120 pages tends to be a red flag. NOT ALWAYS. But seasoned Hollywood readers will treat it as such. Especially when you’re writing in a genre where it’s easy to keep the page count down. This isn’t Legends of the Fall. It’s a mystery thiller. So right away, you’re raising two red flags. And I’m fine if a writer says, “You know what? I don’t care. I’m going to stand by that.” I just like to remind writers that in a profession where you don’t want to tweak the person determining your fate in any way, it’s best to control the variables that you can control.

Onto the story.

Whispers from the Watchtower is a mostly competent mystery-thriller. Both Chace and the daughter are set up well, which is the most important thing to get right, since that’s the emotional through-line of the movie. As long as we want to see Chace save his daughter, the plot is going to work.

I also like how the only way Chace can accomplish his goal is to team up with someone whose profession he fundamentally rejects. We’ve got that built in conflict there, which ensures that there’s going to be tension whenever these two are together. That’s important guys. If you don’t add story components that add tension to scenes, you’re going to have a lot of flat scenes. This is why teaming up two people who dislike each other is such a popular movie trope.

As for the plot, I found it to be above average. The challenge with these missing girl plots is that they’re so common. So the audience is way ahead of you unless you’re throwing something out there they’ve never seen before. And that’s my first beef with “Whispers.” The “strange attractor” to the story – the thing that’s supposed to make it different – is the psychic angle. However, the psychic stuff didn’t play into the story that much. By the end I was convinced Chace would’ve found his daughter without Amari, which left me wondering what the point was of adding a psychic to begin with.

That leads to the “significant trick” I promised you before the synopsis. In order to make any common movie scenario work, you need to add something fresh. The common scenario here is a missing girl. So what are you adding to that that’s new? With Gone Girl, they used an unreliable narrator that resulted in a huge twist. With Prisoners, they focused on false imprisonment and torture of the person our hero THOUGHT was the kidnapper. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo was insanely original with its unique setting, weird titular character, and Nazi connections. Even The Girl on the Train (great book, bad movie) did a deep dive on alcoholism and how it turned its hero into a narrator even she couldn’t trust.

Whispers From the Watchtower adds this in the form of the psychic element, which I was excited about. But it doesn’t deliver on the promise of that premise. Amari’s skill set kicked in when it was necessary for the plot, and was pushed aside when it wasn’t. I don’t know how to describe it. I guess I felt that Jai never committed to Amari’s “power.” Amari could have easily been a really good detective and I’m certain these two would’ve solved the case in the same amount of time.

The script also has some clarity problems up top. Chace’s personal life was unnecessarily complicated. In an early scene, he charges into a motel room where he’s yelling at, I think, a pimp, who’s got this, I think, hooker with him, Reesa. I didn’t know who Reesa was at the moment. But later on she shows up to take care of Emily and I’m thinking, “What the hell is going on here? He’s letting hooker girl take care of his daughter?” Then later, we learn they’re sort of together, but going through a rocky period. Or something?

Then we learn there’s another woman in the movie, Lori, who’s either his wife or ex-wife depending on which part of the script you’re reading. At one point Chace promises Reesa that he’s going to get divorced from Lori (which would make Lori still the wife). However, later, when Reesa is brought to the hospital, the doctors are referring to her as Chace’s wife.

I went back to the earlier scene when Chace tells Reesa he’s getting a divorce and I thought, “Oh, maybe he’s telling Reesa he’s going to divorce HER.” But to be honest, I’m still not sure. The thing is, this is the kind of stuff in a script that a reader should never have to think about. This is the “given” stuff. If I’m easily confused about relationships or who characters are to one another, the script is in major trouble. Professional writers don’t make these mistakes.

I think Jai could add some simplicity to his writing, particularly in the first act, where a lot of information is coming at the reader and it’s therefore easy to get confused. And I’d ask if he could go deeper with the psychic stuff. That’s your strange-attractor so if you’re only half-committed to it, I don’t think it’s going to fly. Still, this genre is a tough sell. I don’t want to send Jai down another lengthy rewrite when I know they don’t make these movies anymore unless they’re high profile novel IP. A sale can happen if the execution is amazing. But even the professionals have trouble with “amazing.” So I don’t know. I don’t want to see a writer pushing something with issues instead of working on something new and exciting with the additional knowledge they’ve taken from this experience.

Script link: Whispers from the Watchtower

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This might seem like a silly thing to highlight. But I liked that when someone on the television spoke, Jai simply put (TV) next to their name. I’m so used to “proper” screenwriting techniques, such as the debate of whether to put “V.O.” or “O.S.” in situations like these, that I didn’t realize a WAY clearer option is to simply put (TV) there.

NEWS ANCHOR (TV)

…Earlier today an Amber Report went out…

You may not like it. But box office is still the main criteria for determining whether people like a movie or not. WITH TWO CAVEATS.

RELATIVITY and EXPECTATION.

Each film’s success is based on the box office receipts relative to the production and marketing budgets. Also, each movie’s success is the final box office number contrasted against what the studio was expecting. This is why Star Wars: The Last Jedi has become the single most difficult movie to pinpoint as a success or failure in film history.

Upon first glance, the film is a juggernaut, taking in $575 million dollars domestically and 1.2 billion worldwide. But is that a success IN DISNEY’S EYES? Before the movie came out, I looked at The Force Awakens 930 million dollar domestic box office and Rogue One’s 530 million dollar domestic box office and said that Disney was probably hoping to AT LEAST split the difference between the two and hit 730 million. The Last Jedi isn’t going to make it that far and will be lucky to hit 630 million. Is that a success or is it a letdown? A cynicist would say it only made 100 million more than a Star Wars movie without a single known Star Wars character in it. An optimist would say that The Force Awakens was an outlier, an impossible to reach milestone, and that The Last Jedi held its own.

Something Disney wasn’t expecting was the out-of-nowhere success of Jumanji. And the reason that Jumanji being a hit, in particular, was a problem for Disney, was that it was aiming for the exact same demo Star Wars was. The reason Jumanji took such a big bite out of The Last Jedi’s numbers was one the pompous mouse house never could’ve predicted. Whereas The Last Jedi aimed to be a crowd pleaser, Jumanji ACTUALLY WAS a crowd-pleaser. And it used a little Scriptshadow trick to get there. What have I always told you guys? Write something that allows actors to play something that they never get to play and good actors will flock to your project. Once you’ve got good actors, you’ve got a shot at making something good. And the team up of The Rock, Kevin Hart, and Jack Black, all playing characters who are NOTHING like themselves, was too irresistible.

Jumanji has another thing going for it that some are arguing has reclaimed the trophy as the the premiere weapon in the battle for box office – word-of-mouth. If you get into a conversation with any random group of people who have seen these movies, you’ll find that both generate conversation. However, The Last Jedi conversation is more volatile. The people who hate it REALLY HATE IT. And so if you’re someone who was thinking about seeing the film, you’re probably leaving those conversations thinking, “Ehh, maybe I’ll wait for digital.” But everyone I’ve talked to who’s seen Jumanji has said, “I was surprised but it’s really good. It’s really funny.” You get nothing but good vibes leaving those conversations, which is why the film’s staying power is so high for a big performer (it’s racing towards $300 million at the moment). I LOVE the fact that word-of-mouth actually means something again because that means studios HAVE TO WRITE GOOD SCRIPTS. They can’t fake it. Anything that gives more power to the screenwriters in Hollywood, I’m all about.

Another film that embodies the power of word-of-mouth is The Greatest Showman. The film had the unfortunate challenge of marketing itself against the juggernaut that is Star Wars. A 250 million dollar marketing machine vs. a puny 40 million dollar campaign. Gee, I wonder who’s going to win the awareness battle there. When the film opened up on Christmas weekend, it made a paltry 8 million dollars and was immediately branded a bomb. Except something funny happened. People liked it. And they told other people that they liked it. And the following weekend, the film saw a 76% jump in ticket sales. And then this most recent weekend, it fell a paltry 11.3%. Usually when there’s blood in the water, a film dies out quickly. This one has not only survived, but thrived, and is currently up to 80 million bucks, off an 8 million dollar opening weekend! It was so off my radar that I didn’t even watch the trailer until I saw all this good box office news. And I loved it. It’s a very strong trailer and looks to be an awesome movie. It also follows two other Scriptshadow tips. First, write about an underdog. There’s nothing like a great underdog story. P.T. Barnum was a poor tailor’s boy before turning into a name everyone around the world still recognizes today. Also, whatever the trend is, find a fresh angle. These biopics have become a dime a dozen. So The Greatest Showman turned its biopic into a musical.

As we move into this new era where audience response is tracked via specific numerical data (as opposed to asking 20 first-weekend once-a-year moviegoers right after they see a film what grade they would give it), it will become more and more important for studios to GET THE SCREENPLAY RIGHT. And that doesn’t mean what you think it means. It doesn’t mean that studios will try to further course-correct their “blockbuster movie” mathematical formula. Quite the opposite actually. What they’ll find is that risk is a key component in driving audience reaction. And you see that with all three of the movies highlighted in today’s article. I don’t know anyone who was asking for a P.T. Barnum musical. That was a huge risk. I don’t know anybody who’d seen the original Jumanji and said, “Yeah, the reboot needs to be turned into a video game.” If anything, on the surface, that sounds like a horrible idea. And for all the crap I’ve given The Last Jedi, that film embodied storytelling risk. They were risks that failed. But you need studios willing to take those chances if you’re going to get those big surprise hits that get audience word-of-mouth going. And that’s great news for screenwriters and creativity in general.

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: (from Black List) A rookie Marine gets stranded on a hostile planet during humanity’s space colonization with nothing but her exo-suit that’s running out of fusion power.

About: Who said the spec sale isn’t alive!? The Expansion Project was preemptively purchased by Warner Brothers for Brad Peyton (Rampage) to direct. The script finished with 15 votes on the 2017 Black List. Leo Sardarian most recently worked as a story editor on the Crackle series, “Start Up.”

Writer: Leo Sardarian

Details: 98 pages

I had only one criteria with The Expansion Project. Don’t be generic. That’s all I cared about. I’ve read sooooooooooo many of these scripts I’ve lost count. The biggest issue with them by far is that they give you nothing beyond the logline. So I was hoping for some surprises or for the script to zig in places where you expected it to zag. Maybe not Kill Snoke zag. But the Vulture is your prom date’s father zag. Let’s see!

An opening title screen alerts us that humanity is colonizing a section of deep space known as the “Frontier.” Elite marines are commissioned to clear new planets for civilized colonization and, if necessary, “quell the rise of profiteering rebels.”

Atlas is one of those marines. She’s getting ready for a drop over giant tree and snow-capped planet GR39. We don’t know much about Atlas other than it isn’t her first choice to be here. Too bad! After putting on her cool exo-suit, she leaps out of the ship orbiting the planet with a group of other marines. Their job is kill some local rebels then rendezvous at the pick-up point.

Within seconds of their jump, they’re being attacked by drones. Atlas is shot up, loses control, and ends up crashing on top of a snowy mountain. Due to high amounts of carbon in the environment, Atlas must keep her helmet on at all times. And her English AI assistant, Gibson, informs her that due to her plasma supply being hit, she only has 22 hours to get to safety before her oxygen runs out.

To add salt to the wound, her leg is semi-broken and GPS is kaput. She’s walking blind. Then, on the way down the mountain, she runs into some damn rebels, who start chasing and shooting her. Remember, Atlas is a marine. And her suit is built for shit like this. The problem is, any sort of help it gives her (helping her run faster or shoot at her enemies) depletes her plasma source even faster, leaving her with less oxygen.

After somehow surviving an avalanche, Atlas powers her way to the rebel outpost, realizing that her only shot may be to charge in, guns blazing, and take everyone out. If she can do that, maybe she can buy more time and find that rendezvous point. She achieves this barely in tact, only to get to the rendezvous point and find out… the ship’s been shot down! There is no rendezvous point! With only 2% plasma left, it’s looking very bad for our esteemed protagonist. Will she find a way out of this? Or will it be Game Over?

Reading The Expansion Project was a reminder of just how different each of the storytelling mediums (novels, movies, video games, plays) are. Sure, there are elements that work across all platforms. I’m yet to find a medium where suspense doesn’t work. But it’s imperative that you understand why each writing medium is different so you don’t stumble into their various pitfalls.

The Expansion Project is so similar to a video game, I kept looking around my couch for a controller. On the surface, this is a good thing. Video games and movies share many of the same qualities. They’re cinematic, fast-paced, and goal-oriented. But there’s one major difference. In a video game YOU ARE THE MAIN CHARACTER. Because you are controlling the hero, you feel like the hero.

The reason this is important is because the first step in any story is connecting the reader to the hero. If you can establish that connection, the reader/viewer will be engaged, because the hero’s plight is now their plight. This is the “hack” that allows video games to keep players so engaged without offering much in the way of character development. The player will play for hours on end, even if all they’re doing is shooting at things and trying to get the next checkpoint, because THEY ARE THE HERO. They are physically controlling their own fate.

It’s for this reason that when you try to move the video game format over to movies, it rarely works. Because the viewer is no longer physically controlling the hero, they’re not as invested. Which means you need to find a different way to get them to invest. Traditional storytelling methods require you to build a backstory into the character, give them flaws, add fears, and inject some personality into the person to build a connection with the viewer THAT WAY. If a video game writer doesn’t understand this, they risk bringing a character into the fold who feels empty. If they then ALSO give us a simplistic video game plotline, it won’t be as effective.

That’s the battle The Expansion Project is waging against itself throughout its running time. Its video game roots are blatantly evident. But it needs to connect us to the hero, Atlas. And it tries a couple of times – there’s a nice moment where Atlas is buried underneath an avalanche and tells her AI about why she joined the marines – but it’s never enough so that we really know this character. And so while I read though The Expansion Project with a certain amount of admiration for the writing, I was never emotionally invested.

There’s only one other way I’ve found that you can make a video game premise with a thin hero work. And that’s to put us in a setting WE’VE NEVER SEEN BEFORE. I’d argue that this is why Gravity worked. That movie also had next-to-zero character development. It also had a video-game like setup (get from checkpoint to checkpoint with time always running out). But nobody had ever seen a movie like that before. And that helped people overlook the problems I’m mentioning here.

So you’re probably asking the question, well then Carson, why did this make the Black List? It made the Black List because the writing was extremely tight and descriptive, and the plot clean and simple. This is about as well as you can write a video-game like premise with a thin hero.

And it makes some good writing decisions along the way. I liked that Atlas’s time limit was not fixed, but that the plasma which was powering her suit was responsible for everything else as well. So when she’s being attacked by enemies and she has to decide whether to use her cannon against them, she must make that decision knowing it also depletes 20 more minutes from her survival time. I love it when characters have to make difficult decisions. And Atlas runs up against that problem constantly here, to the point where you’re saying, “No, dammit! You’re almost out! Don’t do it!”

I’d venture to say that if you liked Gravity or The Martian, you’ll dig this. Personally, I found it to be too familiar. Then again, I read everything. So I’m judging these things on a steeper curve. Check it out for yourself and let me know what you think.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: EMOTIONAL INVESTMENT. It is SO HARD to make a script work if the reader isn’t EMOTIONALLY INVESTED in the hero. You achieve this through a compelling backstory. By adding flaws. By exploring internal conflict. You achieve it with unresolved relationship conflict. You do it with the hero’s actions and choices. — But if all you’re doing is placing a blank canvas in a tough situation and saying, “Care about this,” we probably won’t.