Genre: Biopic/Comedy

Premise: (from Black List) Based on the confusing, sometimes offensive, borderline-insane memories of David Prowse, the irascible Englishman behind Darth Vader’s mask.

About: We just covered The Black List yesterday and this is the first NEW script I’m reviewing from the list. It’s written by two newcomers. Nicholas is a composer who worked in the music department for John Carter of Mars and Dalton is an actor. By the way, if you only came to the main Scriptshadow page yesterday, you did not see the full Black List post. For whatever reason, when I updated, it didn’t catch. So if you only saw the 5-line “Black List Holding Post” message, click here to get the full article.

Writers: Nicholas Jacobson-Larson & Dalton Leeb

Details: 117 pages

What’d you think I was going to choose for my first 2017 Black List review? It’s freaking Star Wars week, man. And by the time you read this, the review embargo for The Last Jedi will have been lifted. Which means we get reviews from people other than those looking to keep Disney happy so they continue to get pre-release access to their big films. Oh, Carson, you’re so cynical! I know. I hate it. However, I am hearing, from the few people brave enough to speak negatively about the film, that the big criticism is that it’s tooooo sloooooow. Hmm, I wonder who predicted that? Could it be the person who said 2 hours and 30 minutes is way too long for a Star Wars film? I wonder. :)

Not to worry. We’re going back in time to when Star Wars was pure. When studios could actually hide all of the negative stuff that was happening on their films. And one of the most infamous of those stories is that of David Prowse, the man who would play Darth Vader.

David Prowse’s career was looking up. He had a role in A Clockwork Orange, and was one of the only actors with the balls to stand up to Stanley Kubrick. At least that’s what Old David Prowse, now 80, is telling the journalist who’s come to interview him about why George Lucas banned him from representing Star Wars.

Prowse dives back into his life as a bullied kid who took up bodybuilding, grew to 6 foot 7, and became enamored with acting. He was in his 40s, with a wife and kids, when a young director named George Lucas wanted him to play the big baddie in his low-budget science-fiction film, Star Wars. Prowse leapt at the chance, especially because this finally seemed like his opportunity to show he could act.

Almost immediately, Prowse put people off on the Star Wars set. He was clumsy, always knocking down and breaking expensive props, and annoying, constantly assaulting George Lucas with pointless questions about his character. But even as the rest of the cast – especially Harrison Ford – turned on him, Prowse was driven by the promise to finally show off his acting skills.

So you can imagine his reaction when he went to the premiere only to find out his voice had been dubbed over by James Earl Jones. Prowse was furious, but encouraged when he learns in Empire that his mask will be coming off. At least now they’ll be able to SEE him. Except that doesn’t turn out the way he hopes either (they used another actor).

In a final grand act of defiance, Prowse informs the Daily Mail that Darth Vader dies in Return of the Jedi, spoiling the film well before its release. That’s the rumor anyway. Prowse claims he had nothing to do with the leak as our journalist wraps up the interview, not quite sure why he wasted the last 4 hours with this man. Did he really learn anything new? Was Prowse being truthful about anything? The only one who will ever know is Prowse himself.

Let me start by saying this. This script has a great final scene. It’s so damn powerful and moving that I was in tears. Unfortunately, the rest of the script doesn’t stack up to the ending, as it’s unsure of what tone it wants to strike and who it wants to portray David Prowse as. And it’s frustrating. Because there’s obviously a lot to work with here.

The script uses the interview framing device to tell its story. This is where an interviewer attempts to find some truth about the protagonist, and before the protagonist can give you that truth, he must tell you how he got there. And hence we have a reason to tell his life story. This device is most successful when the truth the interview is trying to get at carries with it high stakes. The golden example of this is Titanic. They interview Old Rose to find out where the 100 million dollar diamond they’re searching for might be. That’s stakes!

We don’t get stakes anywhere approaching that in Strongman, and this is one of the script’s primary weaknesses. The question that sends us into Prowse’s life is “Why do you think you were banned?” The stakes are so low with this question that within 20 pages, I’d forgotten what the question was. It wasn’t until the final ten pages, when we’re back in the interview room and the question is repeated that I remembered it.

This is a good double-tip for screenwriters using any plotting device. Make sure the goal has some stakes attached to it. And don’t be afraid to REMIND the audience what those stakes are. Even the most attentive audience member is going to have trouble remembering what the point of the movie is if you go 100 pages without mentioning said point.

However, this wasn’t a script killer. This script lives or dies on the depiction of Prowse. And that was a mixed bag. It’s strange. The script is told almost entirely as a comedy. We get lots of scenes like Prowse dressing up a mannequin like Obi-Wan with a mop and doing pretend lightsaber battles with him. There are a good 30 prat falls throughout the script. The goofy characters he played in previous films – like Frankenstein – start following him around in ghost form telling him what to do. And yet it wants you to take Prowse’s journey seriously. When he’s sad about being overlooked, it wants you to be sad too. And it’s hard to do that when Prowse is erroneously remembering Carrie Fisher saying stuff like, “I’m wetter than a Dogobah swamp right now.” (an admittedly funny line)

In fact, I could never tell whether the writers wanted us to laugh with Prowse or at him. But most of it plays like we’re laughing at him, and I don’t think you can do that with a biopic. We have to sympathize with the character, to believe he’s got a leg to stand on. And Prowse is mostly depicted as a clueless unpleasant asshole.

The script shines most in its final third when it begins to ditch its comedy aspirations and focuses more on a man’s struggle to be seen, to be taken seriously, to not have to hide behind masks for the rest of its life. It also covers the complicated fact that Prowse was taken advantage of and used every step of the way of the Star Wars trilogy, even if some of it was his fault. There’s a poignant moment late when Carrie Fisher comes to him and says, “David, maybe people would like you more if you were a little nicer.” And he doesn’t understand what she means. He sees himself as a good guy.

So I don’t know what to make of this. It’s a mixed bag. I will say this – on the comedy side, Harrison Ford is fucking hilarious. He has NO respect for Prowse whatsoever and constantly screws with him throughout the productions, his go-to move being to point his pretend laser at Prowse’s penis and say, “Pew pew pew!” which infuriates Prowse to no end.

And then that ending. You know what? Now that I think about it. That ending doesn’t work unless some of what came before it worked. So maybe I’m underselling this. But it’s a weird script. It’s good sometimes. Bad sometimes. And ultimately leaves you confused about what the point of it all was. Funny. That’s what I’m hearing about The Last Jedi as well. :)

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re a writer writing about an era before you were born, don’t insert phrases and language from the current era. I’m pretty sure nobody was saying, “What’s up, bitches?” in 1977, as Harrison Ford says in this script.

P.S. Please continue to share your thoughts about any Black List scripts you read in the comments. I love seeing what you guys think about these scripts. It also helps me determine what I should review.

You want female assassins with less than 24 hours to do their job? We’ve got female assassins with less than 24 hours to do their job! We’ve also got World War 2 stories. Terminally ill characters. A dozen true stories based on [insert famous person’s name here]. And let’s not forget a big bag of political scripts (equally balanced between left and right leaning, of course). That’s right, your 2017 Black List has arrived!

First thoughts? I’d say that Ruin (review here) is a worthy number 1 script, though I personally would’ve gone with Keeper of the Diary (review here). I’m pumped as all hell that Logan made the list with Meat (review here). Not just because his script deserves it, but because something unique actually made it onto a list that doesn’t celebrate “unique” the way it used to.

As for the scripts that have gotten me excited to read. “Hughes” sounds good. I’ve always wondered exactly that – why Hughes disappeared. Every article on him assumes the reason, but no one’s come out with anything definitive. I want to know the truth! Even if I can’t handle it.

“Valedictorian” has my interest. I’m a sucker for black humor high school stuff, like Election. This sounds like it’s up the same alley. I wouldn’t normally be interested in a true story about a blind musician, but “Key of Genius” made the list with no manager or agent! That’s hard to do! So the script must have something going for it.

“Gadabout” sounds weird and interesting, one of the few truly original sounding scripts on the list. Definitely want to check that out. Star Wars script “Strongman” is one I’ll open up for sure. I haaaaated that script “Chewie” from a few years ago on the Black List. It was the most copy-and-paste-events script I’ve ever read. But David Prowse, the guy behind Darth Vader, is supposed to have a notorious feud going with George Lucas that’s lasted 30 years. And he has good reason. Imagine you shoot an entire movie only to find out once you get to the premiere that they replaced your voice. Oh, and THAT CHARACTER GOES ON TO BECOME THE BEST VILLAIN OF ALL TIME. Yeah, I’d be pissed too.

Bios, about a guy who creates a robot to look after his dog sounds like a tear-jerker with an angle. Obviously influenced by The Dog Stars. And the biopic about the Dating Game serial killer is probably as fertile as you can get with serial killer subject matter. I’ll check that out. I like the idea behind cab-flick “Daddio.” It’s such a movie-specific idea. And very old-school spec-like. I’ll read that. Oh, and “Where I End” gets the highest concept on the list award. So you gotta give that a shot.

The JK Rowling script is probably worth a read if only because it’s the best writing-related rags-to-riches story in history. Might come in handy if you’re struggling to stay motivated on that rewrite. And, of course, there will be surprises, stuff that looks boring but turns out to be amazing. Like this one from two years ago.

Finally, we have some odd connections. There are two scripts covering subject matter that was seen here on Amateur Friday by other writers. One is covering that Jewish filmmaker who made the Nazi propaganda film (Wyler) and the other covering the origin story of Curious George’s author (George). Goes to show you that everybody’s chasing the same stuff.

If you read any of these scripts that haven’t been reviewed on the site, share your thoughts in any of the Comments sections. Together, we should be able to suss out who the real contenders are and who has really good agents.

THE 2017 BLACK LIST

68 votes – “Ruin” by Matthew Firpo, Ryan Firpo – A nameless ex-Nazi captain must navigate the ruins of post-WWII Germany to atone for his crimes during the war by hunting down and killing the surviving members of his former SS death squad.

42 votes – “Let Her Speak” by Mario Correa – The true story of Senator Wendy Davis and her 24-hour filibuster to save 75% of abortion clinics in Texas.

40 votes – “Daddio” by Christy Hall – A passenger and her cab driver reminisce about their relationships on the way from the airport to her apartment in New York.

32 votes – “Keeper of The Diary” by Samuel Franco & Evan Kilgore – Chronicles Otto Frank’s journey, with the help of a junior editor at Doubleday Press, to find a publisher for the diary his daughter Anne wrote during the Holocaust.

22 votes – “Where I End” by Imran Zaidi – In a world where your life can be saved, uploaded to a computer, and restarted in the case of your untimely demise, a husband returns from the dead, suspecting his wife may have been involved in his death.

20 votes – “When Lightning Strikes” by Anna Klaassen – The true story of 25-year-old Joanne Rowling as she weathers first loves, unexpected pregnancies, lost jobs, and depression on her journey to create Harry Potter.

19 votes – “Breaking News in Yuba County” by Amanda Idoko – After catching her husband in bed with a hooker, which causes him to die of a heart attack, Sue Bottom buries the body and takes advantage of the local celebrity status that comes from having a missing husband.

18 votes – “Sleep Well Tonight” by Freddie Skov – Behind the walls of a maximum security prison, a naive teenage inmate and a rookie correctional officer are forced into a drug- smuggling operation, while a looming conflict between rival gang members threatens to boil over.

17 votes – “The Great Nothing” by Cesar Vitale – A grieving thirteen-year-old girl hires a terminally ill, acerbic philosophy professor to prevent flunking the seventh grade. What begins as a homework assignment blossoms into an unlikely friendship and a new appreciation for life that neither will forget.

16 votes – “Trapline” by Brett Treacy & Dan Woodward – A captive boy’s lifestyle is upended when his abductor asks for his help kidnapping a second child.

16 votes – “When In Doubt, Seduce” by Allie Hagan – The true story of the early relationship between Elaine May and Mike Nichols.

15 votes – “The Expansion Project” by Leo Sardinian – A rookie Marine gets stranded on a hostile planet during humanity’s space colonization with nothing but her exo-suit that’s running out of fusion power.

15 votes – “Newsflash” by Ben Jacoby – On November 22nd, 1963, Walter Cronkite puts everything on the line to get the story right as a president is killed, a frightened nation weeps, and television comes of age.

14 votes – “V.I.N.” by Chiara Towne – As Alex Haley struggles to write the autobiography of Malcolm X, his editor at Playboy assigns him a new interview: George Lincoln Rockwell, head of the American Nazi Party.

13 votes – “Come As You Are” by Zach Baylin – An idealistic young woman’s life begins to unravel when her job in social media exposes her to the darkest corners of humanity, sending her on a violent mission to take down not just the web’s most vicious content, but its creators as well.

13 votes – “Hughes” by Andrew Rothschild – The story of writer/director John Hughes, whose emotionally honest high school movies helped to define American culture in the 1980s–but who, at the very height of his success, abruptly abandoned filmmaking for reasons that have never been fully explained.

13 votes – “The Mother” by Misha Green – A female assassin comes out of hiding to protect the pre-teen daughter she gave up years before.

13 votes – “One Thousand Paper Cranes” by Ben Bolea – The incredible true story of Sadako Sasaki, a young girl living in Hiroshima when the atomic bomb was dropped. Years later when she gets leukemia, she hears about the legend that if someone folds one thousand paper cranes, a wish will be granted. At the same time, aspiring writer Eleanor Coerr learns of Sadako’s story and becomes determined to bring her message of hope and peace to the world.

13 votes – “Ruthless” by John Swetnam – After she is diagnosed with terminal brain cancer, a former assassin must carry out one last assignment in order to ensure her daughter’s future.

12 votes – “Jellyfish Summer” by Sarah Jane Inwards – A young black girl’s family in 1960s Mississippi decides to harbor two human-looking refugees who have mysteriously fallen from the sky.

12 votes – “Mad, Bad, And Dangerous to Know” by Jade Bartlett – Based on the book trilogy Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Know by Chloe J. Esposito. An underdog identical twin accidentally kills her too-perfect sister only to discover murder suits her as she becomes compulsively embroiled in the life of a mafia assassin.

12 votes – “Valedictorian” by Cosmo Carlson – An obsessive type-A student vows to secure the valedictorian title before school ends by any means necessary, even murder.

11 votes – “Brosio” by Mattson Tomlin – Inspired by the work of artist John Brosio. When a man begins to lose all of the people close to him in a series of increasingly absurd natural disasters, he must find out why his world has been turned upside down.

11 votes – “Power” by Mattson Tomlin – When a young drug dealer is kidnapped by a man hellbent on finding his missing daughter, they must team up to get to the bottom of the mystery of the intense street drug known as Power.

10 votes – “Arc of Justice” by Max Borenstein & Rodney Barnes – Based on the book Arc of Justice: A Saga of Race, Civil Rights, and Murder in the Jazz Age written by Kevin Boyle. Chronicles the landmark civil rights trial of Dr. Ossian Sweet after he was charged with the murder of a white man.

10 votes – “Don’t Be Evil” by Gabriel Diani, Etta Devine & Evan Bates – Adapted from In the Plex by Steven Levy and I’m Feeling Lucky by Douglas Edwards. Google’s Larry Page, Sergey Brin, and Eric Schmidt struggle with their corporate motto, “Don’t Be Evil,” in the face of their meteoric rise to a multi-billion dollar valuation and a major Chinese hacking incident.

10 votes – “Escape from the North Pole” by Paul Laudiero & Ben Baker – A young girl partners up with an elf, a Russian explorer and a reindeer to rescue Santa Claus from a band of evil elves and save the North Pole.

10 votes – “Fubar” by Brent Hyman – An inept CIA psychologist is embedded on a globe-trotting mission with the agency’s most valuable operative who suffers from an extreme case of multiple personality disorder.

10 votes – “Infinite” by Ian Shorr – Based on the The Reincarnationist Papers written by D. Eric Maikranz. The hallucinations of a schizophrenic are revealed to be memories from past lives where he obtained talents that he still has to this day.

10 votes – “Kate” by Umair Aleem – When a veteran hitwoman is mysteriously poisoned on her last assignment in Tokyo, she has 24 hours to track down her killer before she dies.

10 votes – “Key of Genius” by Daniel Persitz & Devon Kliger – The true story of Derek Paravicini, a blind, severely autistic boy who needed an incredible teacher to help realize his world-class musical ability.

10 votes – “Kill Shelter” by Eric Beu and Greg Martin – A darkly comic crime thriller concerning three groups of people dealing with blackmail gone wrong.

10 votes – “The Man From Tomorrow” by Jordan Barel – The true story of visionary entrepreneur Elon Musk, who after being ousted from PayPal, guides SpaceX through it turbulent early years while simultaneously building Tesla.

10 votes – “Moxie” by Heather Quinn – To combat crime in near-future Los Angeles, the FBI creates supercops based on specific genetic sequences. To their shock, their best candidate is a vulgar stripper named Moxie.

9 votes – “Ballerina” (review here) by Shay Hatten – After her family is murdered, an assassin seeks revenge on the killers.

9 votes – “Escape” by JD Payne & Patrick McKay – When a wrongly accused man is shipped to an Australian penal colony for five years, he quickly realizes his only chance of seeing his family again is to escape the prison with a gang of colors and survive the deadly terrain that awaits on the outside.

9 votes – “Gadabout” by Ross Evans – In 1951, a manufacturing company stirs up controversy when they publish a user’s manual to a time machine called Gadabout TM-1050.

9 votes – “Heart of the Beast” by Cameron Alexander – A former Navy SEAL and his retired combat dog attempt to return to civilization after a catastrophic accident deep in the Alaskan wilderness.

9 votes – “Innocent Monsters” by Elaina Perpelitt – A writer struggling to crack her second novel starts to lose her sense of reality as the book bleeds into her life…and her life bleeds back.

9 votes – “The Kingbreaker” by Andrew Bozalis & Derek Mether – A CIA operative experienced in taking down kings and installing their replacements is brought in to take down a dictator he helped install a few years prior.

9 votes – “Liberation” by Darby Kealey – The true story of Nancy Wake, the most decorated servicewoman in World War II, who led resistance fighters in a series of dangerous missions in Nazi-occupied France.

9 votes – “The Other Lamb” by Catherine McMullen – A young female coming-of-age story set within an alternative religion.

9 votes – “This is Jane” by Daniel Loflin – Based on the book The Story of Jane: The Legendary Underground Feminist Abortion Service by Laura Kaplan. An ordinary group of women provide 11,000 safe, illegal abortions in Chicago from 1968 through 1973.

9 votes – “Wyler” by Michael Moskowitz – With Hitler laying waste to Europe and the United States refusing to answer the call to war, Jewish filmmaker William Wyler risks his career to make MRS. MINIVER, the most effective propaganda film of all time.

8 votes – “The Boxer” by Justine Juel Gillmer – A young Polish man escapes from a concentration camp in which he was forced by SS agents to box other Jews, travels to America to begin a successful career as a professional boxer, and reunites with the woman he lost.

8 votes – “George” by Jeremy Michael Cohen – The true story of the Reys, the husband and wife team who fell in love, created Curious George, and escaped the horrors of WWII in Europe together.

8 votes – “Hack” by Mike Schneider – Based on actual reports, a horrifying look inside the Democratic National Committee hack and the Russian manipulation of the 2016 election.

8 votes – “Lionhunters” by Will Beall – A rogue cop suffers a gunshot wound in 1987 and wakes from a coma thirty years later, where he is partnered with a mild- mannered progressive detective – his son.

8 votes – “The Saviors” by Travis Betz & Kevin Hamedani – A seemingly progressive suburban husband and wife renting their garage through AirBnB become suspicious of their Muslim guests. As they investigate their visitors, they unwittingly trigger events that will forever change the course of human history.

8 votes – “Strongman” by Nicholas Jacobson-Larson & Dalton Leeb – Based on the confusing, sometimes offensive, borderline-insane memories of David Prowse, the irascible Englishman behind Darth Vader’s mask.

7 votes – “Call Jane” by Hayley Schore & Roshan Sethi – Before Roe v. Wade in 1960s Chicago, a pregnant woman becomes a member of an underground group which provides abortions in a safe environment.

7 votes – “Dorothy Gale and Alice” by Justin Merz – Dorothy Gale and Alice meet in a home for those having nightmares and embark on a journey to save the imaginations of the world.

7 votes – “Greenland” by Chris Sparling – A disgraced father is determined to get his family to what, in four days, will be the only safe place on earth.

7 votes – “Jihotties” by Molly Prather – In an effort to fund their start-up, two women catfish ISIS and get more than they bargained for when the CIA recruits them as spies.

7 votes – “The Lodge” (review here) by Veronika Franz & Severin Fiala (Previous draft by Sergio Casci) – A supernatural evil haunts a woman and her stepchildren in a cabin on Christmas.

7 votes – “Meat” (review here) by Logan Martin – A misanthropic man notices bizarre changes in himself, his wife, and the animals inhabiting the territory around their homestead as they attempt to survive self-imposed isolation.

7 votes – “The Poison Squad” by Dreux Moreland & Joey DePaolo – Based on the true story of Harvey Wiley, an eccentric chemist who conducted the first experiment on human tolerance to poison, which catalyzed a movement resulting in the founding of the Food and Drug Administration.

7 votes – “The Prospect – Michael Jordan uses a year as a baseball prospect to find himself after his father’s death.

7 votes – “Rodney & Sheryl” by Ian MacAllister-McDonald – Based on the unbelievable true story of serial killer Rodney Alcala–detectives have estimated Alcala’s body count to be north of 130 victims. Despite being in the midst of a killing spree, Alcala appeared on and won a date with one of the contestants on THE DATING GAME.

7 votes – “Social Justice Warrior” by Emma Fletcher & Brett Weiner – When a liberal, white, college sophomore who knows exactly how to fix society accuses her equally liberal professor of hate speech, it throws the campus and both their lives into chaos as they wage war over the right way to stop discrimination.

7 votes – “The Thing About Jellyfish” by Molly Smith Metzler – After her best friend drowns, a seventh-grade girl is convinced the true cause of the tragedy was a rare jellyfish sting. Retreating into a silent world of imagination, she crafts a plan to prove her theory.

6 votes – “All My Life” by Todd Rosenberg – After discovering the groom has liver cancer, a couple move their wedding date up and get married before he passes away.

6 votes – “American Tabloid” by Adam Morrison – The true story of Generoso Pope, Jr., who with the help of the New York mob turned a small, local paper into the phenomenon that is The National Enquirer, laying the foundation for tabloid journalism as we know it today.

6 votes – “Bios” by Craig Luck & Ivor Powell – In a post-apocalyptic world, a man spends his dying days with the robot he created to look after his dog.

6 votes – “Cancer Inc.” by Marc Macaluso – The true story of the coporatization of cancer in the United States told through the eyes of a British Wall Street analyst who uncovers the corruption behind the approval of a drug intended to treat prostate cancer.

6 votes – “The Fifth Nixon” by Sharon Hoffman – Watergate as experienced through the eyes of President Richard Nixon’s personal secretary Rose Mary Woods.

6 votes – “The Grownup” by Natalie Krinsky – Based on the short story “The Grownup” (review here) by Gillian Flynn. A con woman who pretends to read auras is hired by a wealthy woman to banish an evil spirit from her house, but it is soon clear that the fake exorcist is in over her head.

6 votes – “Green Rush” by Matt Tente – A paroled ex-con agrees to help his daughter steal medical marijuana tax dollars from City Hall.

6 votes – “Health and Wellness” by Joe Epstein – A sociopath obsessed with self-improvement claws her way to the top of the fitness world, leaving a trail of broken bodies in her wake.

6 votes – “Little Boy” by Hayley Schore & Roshan Sethi – The true story of the man

who dropped the world’s first atomic bomb on Hiroshima and his unexpected journey back to ground zero.

6 votes – “On” by Ryan Jennifer Jones – In a slightly futuristic/hyper-efficient Manhattan, a newly-single book editor purchases a customizable sex android to assuage her broken heart. When her toy’s closed feedback loop starts to alter her personality, she must reevaluate the merits of a perfectly- compatible partner.

6 votes – “Panopticon” by Emily Jerome – A look at the criminal justice and private prison system, told from the perspectives of a new inmate, a correctional officer, and a Wall Street hotshot.

6 votes – “Queen Elizabeth” by Shatara Michelle Ford – An uptight high-achieving, black post-grad who becomes (increasingly) irreverent and (slightly) destructive when she realizes that the life she’s living is not the life she wants.

6 votes – “Skyward” by Joe Ballerini – The true story of two families who attempt to escape over the Berlin Wall using a hot air balloon in 1979.

6 votes – “The Sleepover” by Sarah Rothschild – When bad guys break into their home and kidnap their parents, siblings Kevin and Clancy are forced to confront the fact that there may be way more to their stay-at-home mom than meets the eye.

6 votes – “The White Devils” by Leon Hendrix III – Cassius raises his sons, Malcolm and Mandela, isolated and alone in the woods. They have never met another person in their entire lives. The boys have learned to survive and protect their fragile family at all cost. When they find a mysterious wounded white girl, June, alone and lost in their woods, prejudice, lies and love set them on a collision course with the real world that puts all their lives at risk.

Okay I can’t keep it in anymore!!!

I have to speak about The Last Jedi!!!

The newest Star Wars entry is having its premiere tonight. This will be followed by tons of positive social media reaction since Disney will stipulate that you can only tweet if you loved the movie, with Patton Oswalt and Kevin Smith leading the charge.

The film will make 200 million opening weekend solely because it has “Star Wars” in the title.

But then what?

But then what indeed.

While I have my reservations about the film, I love that it’s given us no shortage of things to talk about.

For starters, what nobody’s discussing is that an entire new trilogy is resting on the fate of this film. Everyone’s acting like that trilogy is a foregone conclusion. But mark my words, it won’t be if this movie doesn’t hit 500 million domestic (half of what Force Awakens made).

The magic of Star Wars films has always been in their re-watchability. If a Star Wars movie delivers, nerds like myself will keep going back again and again, pushing that domestic number up higher and higher. If a Star Wars movie doesn’t deliver, someone who was planning on going eight times only goes one. Do the math.

Here are some reasons why this Star Wars may not deliver.

First of all, this is the only Star Wars movie so far that Kathleen Kennedy didn’t clash with the director on. She even clashed with JJ, for goodness’ sake, the nicest guy on the planet. From all accounts, her and Rian Johnson became best friends on The Last Jedi. That may be great for future Christmas Card lists. Not so for creating a good movie. Good movies tend to be born out of conflict. The battles between sides tend to result in the best ideas winning. When everyone’s copacetic, there’s no stimulation to push yourself. The original Star Wars was famous for these battles. I remember reading about a producer – I think the guy who produced The Bridge on the River Kwai – who so believed conflict produced greatness on productions, that if a production was going too smoothly, he would deliberately stir shit up.

Second, the casting on this movie isn’t just bad, it’s uninspired. The three new faces we got are… Laura Dern, Benicio del Toro, and someone named Kelly Marie-Tran. Is the casting of any of these actors getting you excited to see this film? Think about how exciting the casting was for Awakens, particularly Adam Driver, who was a nobody when he got the role. Del Toro is the most interesting of the bunch. But he was just in another space opera movie. Guardians of the Galaxy. Usually, uninspired casting leads to uninspired movies. Not a single sexy casting choice. That seriously worries me.

Third, the running time. We’ve been told that this will be the longest running time of all the Star Wars movies at 2 hours and 30 minutes, which shows a decided lack of understanding of what makes a good Star Wars movie. The best Star Wars movies have tight running times (Star Wars, Empire). The worst have long running times (Phantom Menace, Revenge of The Sith). Long running times usually indicate a writer-director who’s undecided about where he wants to take the movie, so instead of making the hard decisions to focus the story, they instead leave everything in and let the audience make sense of it. This attitude is what led to Matrix 2 and 3, all three prequels, and numerous other bad films.

Is there anything that gives me hope? One thing and one thing only. The trailers are so decidedly average that I’m hoping a decision was made at the studio level to hide all of Last Jedi’s best parts until the movie came out. I imagine a conversation that went something like, “Empire, another second film of a trilogy, became what it was because of its surprises. Let’s do the same thing here.” So I’m hoping I walk into that theater and 90% of what I see is stuff that wasn’t in the marketing campaign. If that’s the case, not only will I be ecstatic, but I’ll give Johnson and Disney major props for doing something that not a single studio has had the guts to do in two decades.

Oh, and I want to see Luke and Kylo have an awesome lightsaber battle.

And I want to see Luke and Snoke have some sort of trippy Force-showdown. That would be cool, too.

Oh, and I want to see this thing kill someone.

Okay, I’m done now.

And a Yoda sighting would be nice, too.

Genre: Supernatural Action

Premise: When the love of his life is murdered by a group of demons, a legendary monster assassin sets out to exact revenge.

Why You Should Read: Because it’s a 90 pages micro script in the vein of “John Wick” with a supernatural twist. I poured into it my passion for the Gothic and macabre, my love of wildly imaginative action and my heart’s yearning for a magical world hidden within our own. Plus, you can play a game of spotting all the references to Edgar Allan Poe’s tales and poems…:)

Writer: Tal Gantz

Details: 90 pages

It’s a week away from the juggernaut that is Star Wars. I’m doing my best not to unleash my predictions on the film, and boy is it hard. Luckily, I have a couple of news items to distract me. One is that Taika Waititi (director of Thor: Ragnarok) is probably going to direct a Star Wars film. I think I speak for everyone – and by everyone I mean me – when I say, “YIPPPPPEEEEEEE!” and “MESSA SO HAPPY DOSEE-DAY!” and “[noise Salacious Crumb makes when he laughs].”

And then there’s this bizarre the-upside-down news that Quentin Tarantino is going to direct an R-Rated Star Trek film. I mean, what the heck is happening??? Star Trek has built its reputation on being squeaky clean. Now they’re going to turn everyone into Jules Winfield? This is most likely an indictment on how desperate poor Paramount is. Although I guess if you’re going to make desperate decisions, you could do worse than Tarantino directing an R-rated Star Trek. I’ve always wondered what Tarantino would do with sci-fi. Wish granted.

While today’s script isn’t sci-fi, it’s firmly based in the fantasy world. How bout that for a segue? Let’s check out the script that won, what infamous commenter 7 Against 7 dubbed, the “Wow Are They Bad” Offerings.

38 year-old James Milton may look like you or me. But don’t be fooled. He’s a monster. He has to be in order to do his job. You see, Milton is a monster assassin.

Badass.

After we see Milton take out a monster known as The Bloody Mummer, who can manifest weapons out of thin air just by imagining them (he mimes shooting an arrow and, voila, an arrow appears, heading straight for your heart), he heads home to the love of his life, Aisling, who surprises him with news that she’s pregnant.

The very next day, Cain, a demon, shows up, and kills Aisling AND the baby growing in her womb, right in front of Milton. Milton does a turbo-grieve before heading to the monster underworld to find out who ordered the hit on Aisling. Turns out it’s some gangster monster named Prospero.

When Prospero finds out Milton’s coming after him, he hires a relentless monster known as The Red Death. After sticking his nose in a few more places, Milton runs into Red Death, and the two have an epic showdown, which Milton comes out of on top. More like The Dead Death.

That means there’s no one left to interfere with his revenge haiku. Milton connects with two old friends, Valentine, a hopelessly romantic imp, and Azrael, a fallen angel, to get the lowdown on where to find and destroy Prospero. He learns he lives underground, in something called the Tunnels of the Dead. But when Milton engages in his final showdown, he’ll learn a devastating truth about the real reason Aisling was murdered.

Let’s start with the obvious. How awesome is the pitch, “John Wick with monsters.”

It’s so awesome I just tried to buy my ticket on Fandango.

And here’s the thing – John Wick’s one weakness – that its mythology and level of detail were lacking? Gantz addresses that weakness in Monster Assassin. Which surprised me. I wasn’t expecting something titled “Monster Assassin” to be so rich and specific.

Whenever I see a really high “high concept” I’m immediately looking for whether this is a lazy poser who came up with a cool idea yet knows nothing about the world he’s writing about or if the writer LOVES their universe so much they want to explore every little crevice of it.

Gantz falls into the latter category. The reason I can tell is because he creates this entire mythology with monsters and rules and potions and spells. I lost count of the sheer number of creatures in this. This isn’t the kind of thing you write off-the-cuff. A lot of thought went into this script. That’s a fact.

And for about 40 pages, I was all-in.

But a couple of things derailed my investment – one that wasn’t Gantz’s fault and one that was. The first issue is that I’m not into this subject matter. It’s the same reason I’m the one person who didn’t love Killing on Carnival Row. As hard as I try to give a shit about fairies, I can’t. I don’t care if an angel gets his wings back or fairy gets its dust back or a unicorn gets its golden snout back. I try. I really do. But I can’t do it.

The bigger issue, though, is that this is an achingly pedestrian investigation. It’s almost like it was plucked out of a “Noir 101” text book. You go to Place A. They tell you to check out Place B. Go to Place B. Bad Guy A shows up to battle you. You beat him but before you kill him, he tells you where Bad Guy B is. He’s at Place C. So you go to Place C. Wash, rinse, repeat. It was annoyingly simplistic and after awhile, I got bored. You put so much imagination into this universe. Why wouldn’t you use some for the investigation?

On top of this, there were too many references to other movies. The mirrors in Azrael’s place were obviously lifted from the paintings in Harry Potter. The Sanctuary, where monsters stay and can’t attack each other, was obviously taken from John Wick. We have the club scene from The Matrix. But the worst of them all was placing a hidden area at a train station. I mean, come on. I saw one Harry Potter movie ten years ago and I know that reference.

If you’re going to take the time to build this extensive mythology, you should take the extra time to build your own original scenes. You’ve put too much into this to look lazy.

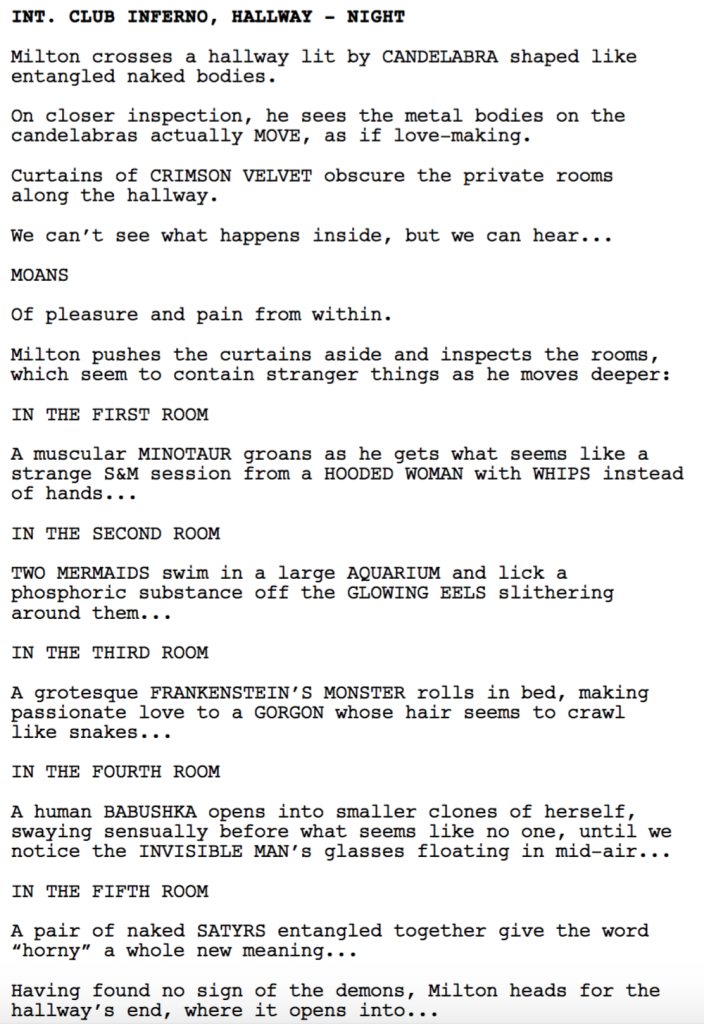

My final knock against Monster Assassin is that HOLY SH#T is it expensive. How expensive?

This shot alone would cost a couple of million dollars.

I don’t usually get on writers for money. A story is what it is. You can’t make a movie called Jurassic World and have the entire thing take place in a basement. People are coming to that movie to see dinosaurs. So I get that we needed monsters here. But there is “monsters” and there is a blatant disregard for financial reality.

Netflix’s upcoming “Bright” uses, arguably, bad prosthetic make-up to create its one major monster-type. AND THAT MOVIE COST 90 MILLION DOLLARS! Going off that number, Monster Assassin would cost three times that at least.

Remember that the similarly budgeted Killing on Carnival Row STILL hasn’t been made and that script has “the best unproduced script in Hollywood” tag going for it.

I hate limiting imagination but the rule here is one that plays across the board in moviemaking. Ask yourself, “Do I really need this shot/scene/character/set-piece?” If the answer is a definite yes, include it, regardless of how much it costs. If not, look for a cheaper way to do it. And remember that cheaper usually forces you to be more creative and come up with a better option.

But yeah, the last thing you want is producers doing a spit take as they read your 40 million dollar version of Hulk vs. Iron Man on page 17. You have to show that you somewhat understand the financial limitations of the business.

That wasn’t the biggest problem though. That was more of a teachable moment. My big problem with this script is the snore-worthy investigation. Do more with that. Be unexpected. Be brave. Try out new things. You can’t use a 50 year old plot template on a movie called Monster Assassin. You gotta be more creative.

Script link: Monster Assassin

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s a neat moment in this script where Milton gets into a fight with someone next to an exotic fish tank. The tank crashes, Milton grabs an eel off the floor, stuffs it in the other guy’s face, and it electrocutes him. — I find that moments like this work best WHEN YOU’VE SET UP THE EEL AHEAD OF TIME. You show the character walk in to the location, you establish the eel in the tank. The owner gives you some history on the plight of the eel. We see the eel use its electricity to stun a fish. Then, ten minutes later, when the fight happens, the tank breaks, and the eel is pulled into the battle, it plays WAAAAY better because we’ve spent so much time setting the eel up. — In Monster Assassin, the time between when we learn about the eel and when it’s used as a weapon is 5 seconds. So it doesn’t have enough time to create an impact.

I was going through the Talkback of last weekend’s Amateur Offerings, and I came upon this comment which unabashedly ripped into the entries. I don’t necessarily like comments like this. I prefer feedback to be more constructive. But if I sense a raw truth to the comment, like the commenter really feels this way and isn’t just trying to stir shit up, I think that’s worth discussing. The truth is, some of the things 7 Against 7 says here, are true. And maybe by talking through them in a calmer more productive fashion, I can help some of you improve the types of ideas you come up with and the scripts you write. So I’m going to go through 7 Against 7’s entire comment, piece by piece, and give you my thoughts along the way. Some of this might be hard to hear. Prepare to be triggered. But hopefully, we’ll all be better writers in the end.

I’ve often wondered why writers couldn’t make a career out of selling spec scripts. These amateur offerings have shown me why.

If a production company had 50 million dollars to spare and wanted to spawn a successful film and possible franchise, these offerings would make them cringe. I imagine these offerings are akin to what’s circulating around Hollywood, and wow, are they bad.

7 Against 7 makes a great point here that writers often forget. If someone has 50 million dollars to spend, and every line of Hollywood box office data suggests that buying a pre-existing property is a better investment than buying an original spec script, why the hell would they buy your spec script? You need to imagine you’re in a room with a big time Hollywood executive and he’s asked you that exact question. Why your script? You better have an answer. The only three answers I know of that hold weight are… 1) You’ve come up with a kick-ass concept that everyone agrees is good. 2) You’ve hit on a current trend, finding an angle just unique enough to separate your script from the pack. 3) You’re an awesome fucking writer who can execute any story, no matter how mundane it sounds. Sadly, if you’re a nobody, people might not even read your script to find out if you’re 3. Logan Martin told me that before Meat landed on Scriptshadow, only 1 guy on Reddit would read his script because the logline wasn’t anything special. So it’s best, even if you are a great writer, to nail number 1 or 2. Increase your reads. Increase your odds.

1) Title: Plummet

Genre: Horror/Thriller/True Story

Logline: Lured by a sadistic killer, a young woman fights for survival in Central Park during the dead of winter. Based on true events.

Based on true events doesn’t negate the fact that it’s the same often retreaded story of a woman being stalked by most likely a male killer.

In this age of Hollywood revelations about stalkers and rapist terrorizing women at work, home and in hotel rooms; this story will motivate no one to go to a theater. Especially not with it taking place in Central Park, NY where there has been many women raped while jogging and walking. Why even write something like this?

“Because this is a contained thriller that really happened about a real serial killer you’ve never heard of?”

I want escapism when viewing movies, not a bludgeoning from reality.

All the complaints about “lack of originality” that ring out from writers whenever Landis makes a sale; yet every week the amateur offerings on this site are terribly unoriginal and uninspiring.

You say “Plummet,” terrible title by the way, is about a woman being stalked by a serial killer. I say it’s just another crumby slasher pick. And I’d rather watch the original “Texas Chainsaw Massacre” or “Friday the 13th” or “Halloween,” or “Sleepaway Camp,” or “Black Christmas” or “Fear,” or “Scream,” or “P2,” etc.

If you’re writing contained thrillers why not tweak the genre like “Get Out,” and “Split” did? If you had an idea like one of the aforementioned, it would be easier to sale; because it’s what producers, managers and agents are looking for right now.

I’m not sure I agree with everything 7 Against 7 is saying here. There is an audience for this kind of movie. There’s something primal about survival and overcoming evil that will never go away in cinema. And something as simple as seeing the girl get away from the killer can be exhilarating. But I agree that the specific concept shaping this getaway isn’t that original. And I like the movies he’s suggesting you look to instead. Get Out and Split. Be a little more creative. A girl running around a park… I suppose that could be okay if it’s executed realllllly well. But the ho-hum setting mentioned in the premise implies that the decisions being made in the script will also be ho-hum. I can’t know for sure. But that’s where my mind goes after reading a logline like this.

By the way, I agree with him about Max Landis. Guys – NEVER use Max Landis or anything he sells as a reason for why your like-minded script should sell. Max Landis is an enigma. There’s never been anyone like him. He posts insane videos on Youtube that go viral. He has a following. He openly trashes major blockbusters then gets hired by the studios that released those blockbusters. He wrote scripts for something like 10 years before he sold anything. There are too many factors going into his success that you can’t quantify or replicate. Don’t worry about Max Landis. Worry about becoming the best writer you can be.

2) Title: MONSTER ASSASSIN

Genre: Supernatural Action

Logline: When the love of his life is murdered by a group of demons, a legendary monster assassin sets out to exact revenge.

There are no stakes, and I can’t figure out who the main character supposed to be exacting revenge against. Some random group of demons? Who is their leader and did they do this for a specific reason? If so, that needs to be mentioned in the logline; otherwise it seems like this will be a pastiche of action scenes with no clear goal and tons of flashbacks divulging backstory. Typical amateur stuff.

Also, demons and angel as warriors has yet to translate well into boxoffice success, religious people don’t like seeing their religion displayed in such a manner. And none religious people think of angels and demon combat as being silly.

“Constantine,” “Dogma,” “Legion” “Ghost Rider,” and “End of Days” all flopped.

I don’t see how any producer or production company could get excited about an idea like yours; which would be better compared to “Constantine” than any of the aforementioned. And that failed as a movie and tv show.

“I poured into it my passion for the Gothic and macabre, my love of wildly imaginative action and my heart’s yearning for a magical world hidden within our own.”

Cool, but what about stakes? Conflict? Conflict resolution? Irony? An antagonist with an coherent goal? Urgency? Set ups and payoffs?

This feels unnaturally harsh, like me reviewing a Rian Johnson film, even though I still don’t understand why the Cinephile community gave this guy a pass for using Photoshop 6 to digitally alter his actor’s faces in Looper. I can only imagine what weirdness he’s going to employ in The Last Jedi. But I digress. 7 Against 7 is right that the logline here is a bit general. I like specificity in loglines because it’s what identifies your script as unique. Still, I understood the problem and goal just fine. Kill the demons. And something about this feels more fun than the failed movies 7 Against 7 listed. “Fun” means a broader audience. Not sure what he means about no conflict. What’s more conflict-filled than taking on demons?

3) Title: Righteous Anger

Genre: Thriller/Drama

Logline: A 17-year-old Syrian refugee becomes entwined in a dangerous world of deceit and human trafficking in his Atlanta community.

Hey kids; let’s skip that live action version of the Lion King and go see this rousing movie about a Syrian refuge and women forced to be sex slaves…it’s in 3d!

Why would I pay to be shown fictional misery, when I can walk down the street and see it in reality? Movies about human trafficking have a terrible track record of not only being snubbed by the Globes and Oscars, but poor box office returns. Which production company would dip into their hard earned coffers to fund this knowing it will neither win awards or be boxoffice hit?

I have to admit I snickered at the idea of choosing between Lion King and a Syrian refugee movie. And 7 Against 7’s sentiment is correct here. This sounds really fucking depressing. However, we have to remember that not every script is vying for a 4000 theater release. If you want to make a more serious movie, you just have to make it cheap. With that said, you have to understand that these types of “heavy subject matter” scripts don’t do well on the spec market unless they’re tapping into an existing hot button topic. Almost everyone who writes this kind of stuff has to raise the money and shoot it themselves. On top of that, Righteous Anger’s logline trails off into obscurity instead of telling us what the script is about. It would be like, if I was writing the Raiders logline, I wrote, “An archeologist who searches the world for rare artifacts goes off and encounters a wild adventure…” You have to give us a more definitive goal, not summarize the general “feeling” of your script.

4) Title: Two-Time

Genre: Crime Drama

Logline: After allegations of game fixing derail his career, an ex-college football star is recruited by a disgraced university booster to steal the three National Championship trophies they helped win.

Why is it called “Two-Time,” if there are three titles being sought-after?

There are no stakes. What happens if they don’t get the trophies back? Nothing, I presume. So they’re willing to be arrested, and have their reputations further ruined, just to get trophies that have no true value?

This idea makes no sense.

Seven Against Seven is right on this one. It’s a script that I resisted posting for a long time for the very reasons he brings up. The story doesn’t make sense. What if he doesn’t get the trophies back? Nothing. He’s in the exact same spot as before. That’s stakes guys. If your character ends up in the same place whether he succeeds or fails, that means there are no stakes. Not to mention, what’s the point of getting these trophies back? You can’t make money off trophies. The only thing they’re good for is displaying. And you can’t do that since it would prove that you stole them back. The more you dig into this idea, the less it makes sense. But at least there’s a story with a goal. And that’s more than a lot of entries offered. So I gave the script a shot.

5) Title: …’Scape The Lightning Bolt!

Genre: Dark Comedy

Logline: Henry has the purest intentions. All he wants is to see his sister happy, but when he accidentally sets her up with a violent psychopath with a peculiar motto (‘Scape the Lightning Bolt)… his life takes an unexpected turn for the worse.

Did you write an entire screenplay around a phrase?

Bazinga! the movie.

What is the main character’s goal? Weather the storm? Kill the psychopath? Couldn’t he just tell her the guy’s a crazy person, show her some footage, and be done with it? I mean, the psychopath isn’t married to his sister.

Now if the guy found out that his sister’s longtime husband was a psychopath that would be more interesting. There would be more attachment and a harder goal of breaking them up. But, as is, your logline is weak and confusing.

Harsh critique but he’s right. Producers would pick this up and think the same thing 7 Against 7 did. The screenplay is about a phrase? How did that end up for Waboom Guy on The Bachelorette? The bigger problem, however, is that you’ve built a movie around the phrase, then don’t tell us what the phrase means. At the very least you’ve got to give us that. But I’ll tell you why I picked this anyway. It sounded different. And sometimes, that’s enough. Readers see so much of the same day in and day out, that something unique will catch their eye. So even with the concept’s limitations, I thought, “Why not?”

Reeves man, stop wasting your time and effort reviewing amateur offerings that aren’t market ready, or saleable. You’re not doing yourself any favors. Find another “Disciple Program,” and get yourself some production credits or something. ‘Cuz this crop of script here, are disheartening.

Just last month Amateur Offerings led to the beginning of a writer’s career. And I’d say we’re consistently finding better material on Amateur Offerings than at any other time. It’s still the best place on the net to discover new talent, in my humble opinion. :)

7 Against 7 is also forgetting something – the power of execution. If a writer has a strong sense of craft or a really unique voice, you can’t always see that in logline form. Also, there’s a bit of a secret involved in logline creation that’s never talked about. When you become a professional, you no longer have to write loglines. The funny thing is that it usually takes the same amount of time to get good at writing loglines as it does to get good at writing screenplays. So by the time we finally have a writer who can write a good logline, they no longer need to. Which is why all the loglines we see in the amateur world are, for the most part, flawed. It’s because they’re not ready yet. They’re still learning.

I think what 7 Against 7 is really railing against here are the ideas. They’re not exciting enough. They’re not the kind of idea where you go, “Oh my god, I have to read that.” Granted, that’s not easy to do. But that should be what you’re aiming for. Also, it’s a hell of a lot easier to write a good logline when you have a good idea. You do that by coming up with a fresh concept that we haven’t quite seen before. Add an interesting main character who encounters a compelling problem. This leads to the primary goal that will drive the story. Then just throw a lot of shit at them to make it hard. There ya go. Now let’s see some kick-ass Amateur Offerings entries!

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. I highly recommend not writing a script unless it gets a 7 or above. All logline consultations come with an 8 hour turnaround. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!