Easily the best TV or MOVIE concept I’ve seen all year. But might it be the best concept I’ve seen all decade??

Genre: TV Pilot – 1 Hour Drama

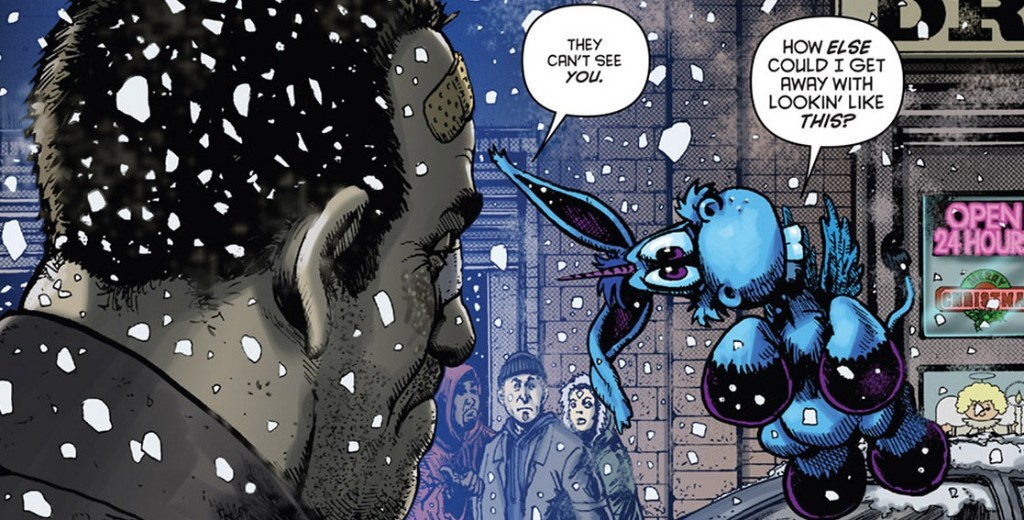

Premise: After a hitman is injured during a job, he wakes up to find a tiny blue horse named “Happy” floating over him, claiming that they’re now a team.

About: Pitched by some as “The Bad Lieutenant meets The Care Bears,” Happy was a four-episode comic by Grant Morrison and Darick Robertson that’s now been adapted for the SyFy Channel. Morrison has brought in Brian Taylor, who’s best known for writing the Jason Statham actioner, Crank, to help him realize his vision.

Writers: Grant Morrison & Brian Taylor (based on the comic with art by Darick Robertson)

Details: 61 pages (Network 2nd Revision – July 27, 2016)

After the depressingly formulaic Rampage, I needed something that was out there, man. I haven’t seen many writers taking chances on the feature end. But there’s plenty of chance-taking on the TV side.

Due to the enormous level of output in TV at the moment, there are two ways to stand out. The first is to buy up a well-known property. Basically, the movie model. And the other is to write something really unique. Today’s script falls into the latter category.

And, actually, today’s script probably has the best screenwriting lesson I’ve discovered in awhile. Because this hook is insanely clever. You see, I read a ton – a TON – of imaginary friend based concepts. It’s the idea every writer goes to when they think they’re writing something original. But today’s script is the right way to do imaginary friends, and the secret to finding a truly original idea.

I’m sure you’re eager to hear more, so let’s jump into it.

“Happy” begins with a creepy teaser. A mother is taking her little girl, Hailey, to see one of those Teletubby-type performances at the local mall. However, with Christmas right around the corner, every family within a 20 mile radius is there as well. That’s how the ultimate parent nightmare occurs. The mother gets distracted for one second… and Hailey is gone.

Cut to a different part of town. Nick Sax is a hitman, and a very un-HAPPY one. We’re told from the drop that this is a man who’s lost everything and has no reason to keep going. But he does. Nick’s just been offered a job to kill the Fratelli brothers, three annoying low-level mobsters.

Sax completes the job, but gets injured in the process. Before he passes out from the injury, a dying Fratelli brother shares with him a password for a drive that contains every single mobster in this city’s secrets.

Sax wakes up in the hospital, but with a new friend. A tiny little blue pony/horse with a unicorn. This is Happy. And Happy is so… HAPPY! He’s excited that Nick’s finally awake. He starts singing to him. He can’t wait for the two to go on adventures together. Nick assumes this is some drug-induced hallucination and waits for it to go away.

Meanwhile, the guy who ordered Sax to kill the Fratellis has ordered someone else to come and kill Sax. But not before he gets that password. Sax is helped by a local female cop, or at least he thinks he is. Not everybody is who they seem, here. And the cop may be working for the guy who’s trying to kill him. Or maybe not!

When the drugs finally wear off, Sax is dismayed to see that Happy the Horse is still around. Sax starts arguing with him, telling him he isn’t into the whole imaginary friend team-up thing. “I never had any imaginary friends anyway,” he tells Happy. Happy chuckles. And that’s when he reveals a bombshell. “I’m not your imaginary friend, Nick. I’m Hailey’s. And I came to you because you’re the only one who can help save her.”

Okay, so let’s break down the genius of this concept. Because if you’re cynical like me, you originally saw the Happy Horse thing and thought, “Zoinks! An imaginary blue horse teams up with a hitman because… COMIC BOOK!”

When that bombshell was revealed that Happy wasn’t Sax’s imaginary friend, but the little girl’s who had been kidnapped in the opening, I was like BSSHSHSHEGGSH! Mind blown. Not just because it was a great idea. But because there was a story-related motivation for Happy to exist.

But let’s get back to the lesson of the day here, specifically the point I originally brought up.

Everybody thinks they’re being creative when they come up with the imaginary friend concept. The problem is, they’re not creative at all. I see tons of them. And they almost always take the same form. An adult is visited by their old imaginary friend from when they were a kid.

Whenever you have an often-used idea, your job is to twist it or elevate it somehow, so that it’s different from everything else out there. The problem is, everybody goes about twisting it the wrong way. They think two-dimensionally when they should be thinking THREE-DIMENSIONALLY.

Two-dimensional thinking is the obvious “next step.” So if you have your “Grown up imaginary friend” setup, a two-dimensional thought might be to make the imaginary friend EVEN CRAZIER! So if the childhood imaginary friend was a bunny, you’d make the bunny a sex-crazed gun-toting wild card! Sounds good, right? But you haven’t really elevated the concept. You’ve just made the imaginary friend a little more interesting.

Three-dimensional thought is when you think beyond what’s right in front of you. You approach the idea from several angles. This is not easy, guys. It’s the quantum computing of idea generation. But that’s why when it works, it results in a killer concept. And that’s what they did here.

This concept is NOTHING if Happy was Nick Sax’s imaginary friend as a child. It’s literally NOTHING. It’s a gimmick. It’s tired. It’s an excuse to get some cool comic book art in. By thinking outside the constraints of that tired setup – what if you were visited by SOMEONE ELSE’S imaginary friend – the idea comes alive. And that’s what happened. And it wasn’t just that it was someone else’s imaginary friend. It’s a little girl’s imaginary friend who’s missing and who needs Sax’s help. Which is why Happy came to him!

I can’t get enough of this idea. I just can’t. This is everything you’re supposed to do with a concept. It’s so damn clever.

And the funny thing about all this is that we don’t get Happy’s reveal until 45 pages in. And before that, I was like, “Eh, this pilot isn’t bad, I guess.” I wasn’t really into it. This is classic noir that, outside of the imaginary friend angle, embraces all the noir tropes a little too eagerly. Which sucks because on concept alone, I’d give this a genius.

So those of you seeing me rave the whole review then only giving this a [xx] worth the read, that’s why. I think this project needs people better than Syfy, no offense. But Syfy has embraced cheese as their curator and this has the potential to be one of the buzziest shows on television with the right people behind it. So I’ll hope that Syfy passes and a Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, or maybe even HBO picks it up. That would be fucking awesome.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Three-dimensional thinking is hard to define. But the basics work like this. When trying to improve an idea, don’t think “bigger, better, flashier.” Instead, take an omniscient view and look at the idea from all sides to see if there’s a hidden angle you can exploit. They do this in the tech world all the time. Uber is an example. People come in and they say, “How do we make a taxi service that’s better than all the other taxi services out there?” Two-dimensional thinking is: Well, we add TV in the back and we make the cars cleaner and we only hire drivers that are nice and courteous. All that stuff is fine but it doesn’t change the game. Three-dimensional thinking is: Eliminate the taxi altogether.

If all is right with the world, you should be receiving a Scriptshadow Newsletter with a brand-spanking new top secret sci-fi project script review by tomorrow morning. If you want to sign up for the Scriptshadow Newsletter, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “Newsletter” and I’ll add you on.

Genre: Sci-Fi Adventure

Premise: Based on the sorta-famous 1980s video game, Rampage, three animals are infected with a virus that makes them grow exponentially larger and stronger.

About: Rampage is one of the more improbable projects out there. Based on an arcade game that only true arcade geeks remember, the project somehow got the biggest movie star in the world, The Rock, to sign onto it. I’m guessing by offering him an unheard of amount of money. The original script assignment went to Ryan Engle, who wrote Non-Stop (Liam Neeson). Current revisions were done by Adam Sztykiel, who penned the Robert Downey Jr. and Zach Galifianakis road trip comedy, Due Date, as well as 2015’s Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Road Chip. The film is directed by Brad Peyton (San Andreas), and will be a big 2018 summer release.

Writers: Ryan Engle and Adam Sztykiel

Details: 116 pages

Here’s a little industry trick.

If you want to make a giant movie that’s similar to a major property, simply find an obscure property in the IP universe that’s in a similar vein, option it, and make that movie instead.

How do you make Godzilla or King Kong if you don’t have the rights to Godzilla or King Kong? You option little known 80s arcade game, Rampage! That’s how.

I’ll be honest. I was a BIG Rampage fan back in the day. Giant animals climbing buildings and destroying shit? How could you NOT be into that.

But how do you make a movie based on that? How do you create a mythology to make the animals big in the first place? And once you have them, how do you get them into the city? And once they’re in the city, how do you get all three of them climbing buildings? Why would giant animals all of a sudden be like, “Yo dude, let’s climb these buildings!” And how do you make it all believable? At least in relative movie terms? That was the challenge today’s writers had. Let’s see how they did.

Davis Ridley works at the San Diego Zoo as a gorilla wrangler, and there’s nothing he loves more. That’s because Davis gets along with animals better than he does humans. “You always know where you stand with animals,” is Davis’s mantra.

Meanwhile, up on the space station, because of course there would be a space station, a top secret project has gone haywire, killing all the scientists inside and sending the station spiraling into earth’s atmosphere. The station breaks into three pieces, crashing in three separate areas of the U.S.

One of those pieces lands near the San Diego zoo, where Davis’s favorite gorilla, a silverback named George, gets a hold of it. A few hours later, he’s leapt over the 20 foot high enclosure, found a bear, and mauled it to death. Davis is worried.

Soon after, Dr. Kate Caldwell shows up. Kate used to work for the space station company before getting fired last year. Kate is one of the few people who knows what’s going on. Any animal that gets a whiff of her secret virus will start growing infinitely bigger and stronger. And if you guessed that Kate and Davis don’t get along yet their interactions include a steamy romantic subtext, you’d be right.

Meanwhile, back at the Sears Tower in Chicago, the brother-sister CEOs of the space station enact a protocol-beacon of sorts that trigger the infected animals to come to them. I’m not sure what their ultimate plan is once these monsters show up in the middle of one of the biggest cities in America, but who cares! It means giant animals climbing buildings, baby!

Along with George the Silverback Gorilla, there’s a giant-ass wolf and a giant-ass crocodile also coming to join the fun. Will they make it to Chi-Town? And if so, how much building-climbing will they get in before the visual fx budget runs out? And how does The Rock fit into all this? You’ll have to wait until 2018 to find out, cause no way am I spoiling the rampage!

It was really interesting reading Rampage after the sci-fi script I review in the newsletter. One is the very definition of “taking chances,” while the other, Rampage, is the essence of formulaic. And I’m not saying that’s a terrible thing. 200 million dollar movies are going to be more formulaic than not. But therein lies the challenge. You have to take chances and be original SOMEWHERE. Or else there’s nothing to distinguish your movie, nothing to make it stand out or memorable.

Rampage was painfully predictable. It’s got the overcooked character flaw for its protagonist (he likes animals more than humans). It’s got the forced sexual conflict with its leads, Davis and Dr. Kate. All the plot beats, such as the inciting incident and act turns and relevant twists come exactly where they’re supposed to.

I struggled to find even ONE thing about this script that was a unique choice. I eventually came up with the CEOs of the space station company. The writers could’ve gone with the cliche mustache-twirling villain, but made it a brother-sister team instead. So at least there’s something original in the script.

Look, I’m not going to pretend that writing these scripts is easy. When you’re sending drafts into producers, they’re not coming back at you with, “Less Jurassic Park and more David Lowrey’s ‘A Ghost Story.’”

So the question becomes, how DO you make these scripts original?

I think it’s those little choices, like the brother-sister CEO team. If you can make a bunch of little original choices like that, they accumulate and the film starts to feel like something of its own.

But you also have to get the characters right. A huge problem writers run into with these movies is they just accept generic archetypes. When they’re writing Davis’s scenes, they’re not thinking, ‘What has this person been through in their life?’ They’re thinking, “What cool one-liner could The Rock say here?” And I admit, that’s fun to do. But I’d argue that understanding a character’s backstory and biography in a 200 million dollar movie is more important than in some Oscar-bound indie flick.

In the indie flick, the gritty dark palette of the screenplay leads us to give the characters the benefit of the doubt. In contrast, you have to actually work to convince us that the main character in a giant sci-fi adventure film is a real person. And if you don’t do that work? The character feels fake. And by association, everything he engages in feels fake.

Davis’s “Me like animal more than human” m.o. is a dime-store flaw. It’s the very definition of movie logic and doesn’t take into account how a real human being could’ve gotten to this place in their life, or if he should even be there at all.

I don’t know. Maybe I’m digging too deep. Maybe they’re just trying to make the Godzilla/King-Kong version of Tremors. A goofy fun silly adventure where nobody takes what’s happening too seriously. I just think it’s dangerous to do that. Whenever you move away from truth and real life, you get empty movies. Which is why I probably won’t see Rampage unless it has the best trailer ever.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The forced “we don’t like each other because this is a movie” relationship between Davis and Dr. Kate really annoyed me. Remember guys, CONFLICT is not a reason for a character’s action. People don’t engage in conflict because they want to engage in conflict. In real life, there’s always a REASON behind the way people act towards one another. In Seinfeld, there was this super annoying character named “Bana,” a terrible comic who Jerry despised and never wanted to talk to. The Seinfeld casting directors scoured the acting ranks to find Bana. The direction they kept giving during auditions was, “He’s really annoying.” So hundreds of actors came in and they tried to be REALLY ANNOYING. The problem was, that’s all they were trying to be. Annoying. There was no reason behind their annoyingness. It was just to meet the character requirements. When the actor who eventually got the Bana part came in, he recognized that this lack of reason behind the annoyingness was a problem. So he asked, “WHY is he annoying?” And he came up with this little adjustment where Bana just really wanted to be Jerry’s friend. THAT’S why he was annoying. The casting directors were instantly on the floor laughing at the interpretation and the actor became one of Jerry’s favorites. Jerry would continue to find as many ways as possible to fit Bana into episodes. The point is, characters don’t just do things cause: SCRIPT. You have to find reasons behind why characters are acting the way they do. Then, and only then, will they come alive.

What is anchoring and why is it important?

Let me start off by saying that anchoring is an advanced writing technique that beginners shouldn’t worry about yet. If you’re a beginner, worry about structure, keeping your descriptions succinct, getting your scenes down to a manageable length (under 2 and a half pages), not writing on-the-nose dialogue, arcing your characters. Anchoring is not going to help you if your fundamentals are so bad that your script is unreadable.

But once you’ve got all that down, anchoring can help you take your screenwriting to the next level. What is anchoring?

Anchoring is the process by which you anchor characters, plot points, story beats, and other story choices to REAL LIFE EXPERIENCE.

A common critique you hear a lot of writing teachers use is that there’s no “TRUTH” to a character (or to a moment). What they mean by this is that the character feels “written,” they don’t feel “true-to-life.” And that’s because, most likely, you completely made them up.

“But Carson, isn’t that the point of writing? To make stuff up?”

Yes and no. You want to make things up that give the reader a great reading experience. But that doesn’t work unless the reader BELIEVES what’s happening on the page. And to make them believe, your story must feel as real as possible (relative to the genre and movie type you’ve written).

This is where anchoring comes in. Let’s say you’re writing a comedy script. Your main character is the straight guy and you want to add a “zany best friend character.” If you construct that character completely out of thin air, he’s not going to work. He’ll feel made-up, cliche, thin, you name it. However, if you had, say, a crazy roommate in college, and you based your zany best friend on that roommate, now that character is going to carry a truth, a “realness” to him or her. Why? Because they’re based on a real person! This is anchoring.

Anchoring isn’t limited to character creation. Anchoring applies to any situation you write into your script. For example, if your characters have to go to a big company event, but you yourself have never been to a company event, you need to find a way to anchor that. Maybe you once attended a giant wedding. Weddings tend to have crossover with corporate events as both include a meal, socializing, music, drinking, etc.

What you’re looking for is specific stuff you can pull from the wedding to use at the company event. For example, maybe you remembered an annoying mariachi band that kept coming around and playing when no one wanted them to. Or maybe you ordered a drink at the bar only to learn that you had to pay for it. Maybe the planners messed up and didn’t include enough tables, forcing you to eat dinner while standing up.

Specificity sells realism and anchoring is a great way to add specificity.

I’ve discovered that there are five main levels to anchoring. Preferably, everything you anchor should be a level 1. But if that’s not available, you’ll have to go further down the list. Just know that for every level you go down, the less realistic your characters or situations will be. So proceed through these lower levels with caution.

LEVEL 1 ANCHORING – PERSONAL LIFE

This shouldn’t be surprising. Ideally, you’d like to anchor as much as you can to your own personal experiences. These are the things that will come off as the most truthful. People will read your stuff and give you compliments like, “It just all seemed so real.” That’s because it was real. A good example of this is Garden State. There was a scene in that movie where Zach’s character is about to get into his car the morning after a long night of partying and sees a ripped-off gas nozzle sticking out of the tank – you don’t just make that stuff up. That either happened to him or someone he knew. Which leads us nicely into Level 2.

LEVEL 2 ANCHORING – FRIENDS AND FAMILY

While not as good as anchoring something to your own life, anchoring stuff to your friends and family’s lives is the next best thing. If you want your hero to work in an office but you’ve never worked an office job in your life, anchor the job to your best friend who works at an office. You may not live their life, but you’re around them enough and heard about their experiences enough that you can craft a pretty solid approximation of the job. Likewise, if you need to write a sex addict into your script and have a friend who’s an alcoholic, you can anchor a lot of your character’s behaviors to your friend’s. That’s an important thing to note about anchoring. It doesn’t have to be exact. If you need to write a teenaged bully into your high school comedy, there’s no law that states you can’t anchor that bully to the Starbucks barista with an attitude you deal with every morning when you buy your coffee.

LEVEL 3 ANCHORING – SECOND HAND STORIES

We’re getting further away from the truth, which means you want to think twice about using this in your script. But occasionally you’ll hear friends, family members, or coworkers tell stories about someone they know or an experience they had, that was interesting in some way. Since you’re a writer, you’ll naturally want to include some of these moments in a screenplay. The problem is these stories are far enough away from personal experience that they contain a dream-like quality to them. They lack the specificity to make them believable. For example, I knew a guy through a friend who used to play on the professional tennis circuit. One night he told me this elaborate story about getting cheated by an umpire at the French Open. It was a great story. And I tried to anchor the essence of the story into a baseball script (with the home plate umpire committing the same sin on a player). But it never quite worked because I didn’t know all the details. I wasn’t there to smell the red clay, to endure the impatient booing of the crowd, to feel the pressure that, if I lost that match, I didn’t have enough money to get a plane back to the U.S. Second hand story anchoring can work. But it’s never going to feel as realistic as Level 1 or 2 anchoring.

LEVEL 4 ANCHORING – MOVIES AND TELEVISION SHOWS

This is where the majority of beginner and intermediate writers anchor their writing – to stuff they’ve seen. Need a villain? Hans from Die Hard worked. I’ll just create another version of him! Need a good chase scene? I loved that chase scene in Fast and the Furious 4. I’ll change the cars from Corvettes to Maseratis and nobody will be the wiser! This is literally the WORST thing you can do when you’re writing a script. It’s why so many amateur screenplays are so bad. The writers are just rewriting what someone else wrote. With that said, anchoring off of other movies can still work if you follow a couple of simple rules. Rule #1 is to twist whatever you’re cribbing enough so that nobody will be able to tie it back to the anchoring source. For example, if you made your “Hans” character a woman and had her use sexuality as a weapon, nobody’s going to be saying, “This is just like Hans from Die Hard!” Rule #2 is to favor movies that are old or unpopular. Quentin Tarantino built much of his career around this. Anchor characters and situations to barely-seen movies and nobody will call you out except for extreme cinephiles.

LEVEL 5 ANCHORING – YOUR IMAGINATION

If you try and craft a character strictly out of your imagination and don’t base them on anything or anyone you know or your friends and family know or who you’ve heard about second-hand or who you’ve seen in other movies, it’s 99.9999% likely that that character is going to feel written. For example, a flea-market furniture maker who fought in Vietnam before becoming a pacifist sounds like a really interesting character on paper. But if you’ve never been to a flea market and you don’t know anyone who’s sold self-made furniture or fought in a war or who’s a pacifist, it’s highly likely that character is going to read as total bullshit. BUT! Maybe you knew a hippy when you first moved to Los Angeles who made and sold jewelry on the Venice Beach strip and maybe your dad’s friend who used to come by for dinner twice a year fought in Vietnam and so if you could somehow combine those characters into one, there’s a shot at making that character work. That’s the power of anchoring.

A couple of final points I want to make. Where non-anchoring hurts you most is when you write a big character or include a big plotline that a lot of people are familiar with, but you know very little about. This makes for a lot of people who can call you on your shit. And they will. For example, if neither you nor anyone you know has kids to parent, yet your movie has a large parenting component, you’re going to get called on it. If you write a cop and the only thing you know about cops is what you’ve seen in movies – called on it. If a 60 year old who doesn’t even know what Instagram is tries to write a teenager – called on it.

When dealing with these issues, the solution may be to ditch the storyline or character you know so little about. Or re-write them into something you know well.

Finally, I’ll address something a lot of you are probably wondering. “What about if you’re writing in a completely imaginary world? Like Star Wars or Harry Potter?” When you’re writing inside of imaginary worlds, the big focus will be on anchoring characters. If they’re believable, everything surrounding them will be as well. For example, you may not know anyone who owns a floating city like Lando Calresian. So how do you write a character like that? Well, maybe you have this one uncle who showed up to every family reunion who was soooooo charming. Yet, if you talked to anyone behind closed doors, they told you he was involved in some shady shit. That’s how you create Lando Calresian. You base him on someone you know. And once we believe in that character, we’ll believe in that big floating city he runs.

I hope this is helpful. Feel free to share your own anchoring experiences in the comments section.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. All logline consultations come with an 8 hour turnaround. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Genre: TV pilot (comedy)

Premise: A low-level hitman heads to LA for his latest job, only to inadvertently befriend his target, an aspiring actor.

About: Today’s script was written by SNL vet, Bill Hader, and Silicon Valley producer, Alec Berg. Whereas Netflix has embraced the “throw a bunch of shit at the wall and see what sticks” strategy, HBO still has to slot shows into a proper schedule, and is therefore more discerning about what they air. It’s for this reason that they still have the edge over Netflix. It’s also why, when something gets an official commitment from the network, you know it’s beaten out a ton of other quality material (last I heard, HBO had something like 100 projects in active development).

Writers: Alec Berg & Bill Hader

Details: 36 pages (Third Draft)

Since yesterday’s script was the antithesis of funny, I spent the last 24 hours on a comedy script hunt, a laugh-quest, if you will. After traversing many of Los Angeles’ landmarks – Randy’s Donuts, Rodeo Drive, the Capital Records building, I met a sinewy little fellow who called himself “Maurice Bubblestilskin the III.” “Psst,” he said to me, while I tried to hail a Lyft. “Psssssst!” he said again. And from under his cape, he passed me this, “Barry.” ‘Best project HBO’s got going for it,” he assured me, before slipping back into his tent and screaming at himself for 5 minutes. And that’s how I came across Barry.

Hitman-Comedy is a sub-genre with a lot of history behind it, and that’s because, like all good comedy, it’s built on top of some heavy irony – A comedy… about killing people. I’m surprised we don’t yet have the definitive hitman comedy. Could there be some flaw in the concept that keeps these scripts from being great? I’m sure we’ll find out. Grab my hand and hop in my Scriptshadow canoe while I paddle you through Barry’s plot.

Barry is lonely. But WAY worse than that, he lives in Cleveland. If there is a more hideous fate than being lonely in Cleveland, I don’t know what it is. The only time Barry has anything to do is when he’s on the job. Barry is a hitman, you see. He’s paid to kill people.

Barry has a Charlie’s Angel’s disembodied boss named Fuches who calls Barry whenever he’s got a job for him. And Fuches has a new target in Los Angeles. If Cleveland is our idea of hell, Los Angeles is Barry’s. Barry begrudgingly flies to LA, where he’s introduced to a medium-grade Chechen crime boss named Goran Pazer. Pazer is pissed because some trainer named Ryan Madison is fucking his wife.

Pazer has hired Barry because he can’t have his fingerprints on the murder. And it’s a fairly simple job. Ryan is a nobody trainer. So, theoretically, all Barry has to do is wait until he gets home and put a bullet in his head. But Barry makes the mistake of following Ryan to an acting class (yup, it’s LA, so Ryan is also an actor!). And after being lured into the class by a beautiful young actress, Barry bumps into Ryan, who assumes he’s a fellow actor, and asks Barry to do a scene with him.

Barry does the scene with Ryan, likes it, and is then pulled out for drinks with the acting class. Being such a lonely guy, this is an exhilarating experience for Barry. But now he has a dilemma. He has to decide if he’s going to kill his new buddy, Ryan, or wiggle out of his contract and pursue his new dream – ACTING! Unfortunately, Barry’s hand is forced when the Chechens step in and take care of Ryan on their own. The plan is to kill Barry next, but Barry kills them first. And that’s how Barry finds himself an aspiring actor in LA… with the Chechen mob after him.

I want to take this opportunity to reiterate a great screenwriting device that works every time you do it. It’s mostly a comedy thing but you can use it in any genre. It’s called the “Mid-Scene Twist,” and the structure behind it is quite simple. You make the audience believe the scene is one way. Then, at the midpoint, you reveal that it’s something completely different.

We open on Barry, washing up in his bathroom, getting ready for the day. He looks at himself in one of those, “What the hell am I doing with my life?” ways. He plucks a gray hair, frowns, straightens up, then walks out. As he walks through his apartment, we notice… GUN HOLES IN THE WINDOW? Oh, and then there’s a murdered dude on the floor. This isn’t Barry’s apartment. No, Barry is a hitman, and he’s just finished a job.

In this case, the mid-scene twist was subtle. But it’s a lot more interesting than say, showing the hit. We’ve seen hits before. Hell, I think every single movie in history has a hit. So to start with a mid-scene twist was a much stronger choice.

A more aggressive form of the Mid-Scene Twist came at the beginning of an, unfortunately, terrible movie – Snatched (that Amy Schumer Goldie Hawn jungle flick). But it was a good scene!

In it, Amy’s character is at a clothing store, picking up dresses to try on, excitedly telling the employee helping her about the amazing vacation she’s about to go on with her fiancee. The employee seems a bit overwhelmed as Amy continues to grab new articles of clothing and gab away.

Finally, when the employee can get a word in edgewise, she says, “So are you going to set me up with a fitting room?” And we realize that it’s actually AMY who is the employee, and the other girl the customer. Amy then becomes defensive, frustrated that this woman isn’t appreciating her upcoming vacation, and the two eventually go their separate ways. It’s a simple premise, the mid-scene twist, but very effective when done well.

Start us off one way. Twist it into something else. Usually the opposite of what we assumed.

As for the rest of Barry, it was good. It was a little different. More importantly, it was unexpected. And this is where all the amateur writers screw it up. Because I know the amateur version of this script. I’ve read it a million times. Barry has to kill a guy. He goes over to the house. But, oh no, ZOINKS, the guy shows up with the wife he’s fucking! And the only place for Barry to hide is… ZOINKS!… UNDER THE BED! So he has to hide under the bed while the two have sex! Oh the shenanigans! Oh how the hilarity is ensuing!

No.

NO NO NONO ONONONOONNOONONOON

If you write that version of the script, you are a failure as a writer. I’m not kidding. Your job as a screenwriter IS TO GIVE US THE UNEXPECTED. If you give us what we expect, why would anyone pay you? If they want the version everyone expects, they write it themselves. They pay you to come up with unexpected complications and obstacles that keep the story fresh.

And that’s exactly what happens here. I never thought in a million years that Barry would get drawn into an acting class, and start to like acting, and start to like a girl in class, and wonder if he wants to move to LA, and kill the guys who hired him instead of the guy he was supposed to kill. I didn’t expect any of that. And so, even if I don’t like what the writer did with the story, I acknowledge that he gave me something unique.

Now, as it so happens, I did like what the writers did here. My only issue is with “Barry” is Barry himself. He’s such a quiet character. Quiet characters are hard to make interesting. And to build an entire show around a quiet character is more challenging than they may be anticipating. But I was still intrigued by what Barry would do next. That’s a sign that I’m connecting with the character.

We’ll see what happens once this hits the air. Im predicting, at the very least, a multiple-season pick-up.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When writing TV shows, think about character advancement. Where are they in their career now and is there opportunity for them to move up over time? Because that’s where you’re going to find your Season 2, Season 3, Season 4, is in the character advancing in their career. Breaking Bad is the most obvious example of this. He’s a small time drug dealer at the beginning. Then, by the end, he becomes a major force in the meth business. Here, Barry is a low-level hitman. So there’s lots of room for him to move up the ladder.

Genre: Family Comedy

Premise: The former lead singer for an Alt-Rock band must take his kids on the road with him when the band reunites for one of the biggest music festivals in the world.

About: Mega-writer Drew Pearce (Iron Man 3, Sherlock Holmes 3) teamed up with Jason Segal (The Muppets, Sex Tape) to sell this pitch for north of a million dollars a few years back. The scribes then went to work, but nothing ever came of the project. Today, we’re going to find out why!

Writers: Drew Pearce & Jason Segel (loosely based on the doc, “The Other F Word”)

Details: 106 pages (5/6/14 draft)

The aging rock star concept is one I see a lot. I think it’s because the rock star is the quintessential embodiment of Peter Pan syndrome. People enjoy the irony of seeing an aging rock star forced to grow up. But it’s also a sub-genre that’s never quite been nailed.

Are Drew Pearce and Jason Segel the writers to finally nail it?

Jim Stent is 35 and father to 14 year-old Tara and 8 year-old David. To people who grew up with normal lives, getting to be a dad to two wonderful kids might be the pinnacle of their lives. But Jimbo used to be a rock star! Well, that’s putting it strongly. But he was the lead singer of a fairly well-known alt-rock band in the 90s called Delinquents (no “The!”). And once you’ve had thousands of fans screaming your name, you’re not exactly pining to pack lunches on Monday morning.

To add insult to injury, Jim’s wife, Suzanne, is becoming the next Stephanie Meyer. Her werewolf books have gotten so popular that when you google Jim Stent’s name, his band doesn’t even come up anymore. He gets, “Suzanne Stent’s husband” instead! Jim is feeling more irrelevant every second.

So when his old guitarist, Richard, stops by and says that the 6th biggest rock fest in the world wants Delinquents to reunite, Jim is intrigued. But with Suzanne about to go on a book promotion tour, Jim’s stuck on daddy duty! That’s when Jim comes up with a plan. He’ll tell Suzanne that he and the kids are going on a camping trip instead, then go on tour.

Jim and Richard get the rest of the band back together (crazy Gene Biscuits, and mute bassist, and the lone female in the band, Blue). The plan is to play four small venues so they’ll be ready for the festival. Off on tour they go. But with kids!

The mini-tour is an ongoing balancing act as Jim tries to protect his kids from the unseemly aspects of rock glory. But in doing so, is unable to channel his inner rock star, leaving his performances devoid of energy and coolness.

Gene Biscuits finally has to step in, telling Jim that he’s become a lame dad. And that if Delinquents return is going to be successful, he’s going to have to leave the “dad” behind and let loose! But therein lies the question. Can Jim leave the dad behind? Or is that who he’s become?

Whoa.

I mean.

Whoa.

I’ll be honest. I don’t like this genre. Personally, I think family comedy is where screenwriters go to die, the last leg of the tour, if you will. But there’s a way to make these movies work. It’s not like by deciding you’re writing a family comedy, the movie will automatically suck. School of Rock was a family comedy and it was good.

Here’s my operating thesis on what went wrong here. Family comedy works best when you define the line of what’s “too far” for a family comedy and you spend the entire script going right up to that line, even inching past it. Because that’s what makes people laugh. They don’t laugh at the safe obvious stuff. They laugh at stuff that’s gone a little too far, the stuff they’re not sure they’re allowed to laugh at.

School of Rock is actually a good example of this. Jack Black’s character perfectly walked that line of liking the kids but also making fun of them when a good joke presented itself.

Delinquents never gets anywhere CLOSE to that line.

The main joke in the movie is Jim rewriting “kid-safe” swear words that all of the band must use. You can’t say, “Motherfucker.” You must say, “Motherfrogger.” There might have been a version of this joke that was funny if the substitutions were funny. But they were all lame. And, jesus, swear jokes have been beaten to death in this genre. As far as I’m concerned, you get one “EARMUFFS!” zoinks swear joke in a family comedy and that’s it. Go challenge yourself and find some new jokes.

The rest of the script is similarly lazy.

A few weeks ago, we talked about the power of saying “no” to your characters. The more you say “no” to them, the more they’re forced to fight for what they want. And that’s the most entertaining thing about watching a movie – seeing your hero work hard to get what he wants.

But I want to talk about a bad type of “no.” The “fake no.” The “fake no” is when you say “no” to your character when it doesn’t make sense. The only reason you’re doing it is because Scriptshadow told you to. So in the first few pages, we establish that Jim is miserable and misses his former life as a rock star.

Then Richard shows up and says, “Hey, do you want to get the band back together?” Now, in real life, what does Jim say here? He says yes! This is exactly what he’s been waiting for! But because they needed conflict, they had Jim say no for NO OTHER REASON than this was a screenplay.

This leads to a big scene where the families get together for dinner and Jim “feels out” what people think about a reunion, the idea being that if it’s a positive reaction, he might be up for it. But the scene is lifeless because the device that got us here (the “fake no”) was so transparent.

And while the average viewer isn’t going to understand any of the terms I’m using above. Believe me. They subconsciously know when something’s off. You can’t bullshit audiences. They’re smarter than you think.

This script just needed to be more dangerous. It needed to take more chances. And I’ll give you an example of one of the first chances they should’ve taken.

The script starts in the present, with us getting to know Jim, the lead singer, and Richard, the lead guitarist. We also meet Suzanne, Jim’s wife. We then learn that the reason the band died was because Jim got Suzanne pregnant 15 years ago. He had no choice but to quit. He had to start a family.

Quickly after this present-day setup, we flash back to 15 years ago, when the band was on top of the world. Backstage, after a big concert, a 20 year old Suzanne walks into the room. She walks right up to Jim and gives him a big kiss. A few minutes later, she reveals that she’s pregnant, and we cut back to the present.

First of all, we didn’t need this scene. This was exposition that was already hinted at and could’ve easily been handled inside of one present-day line of dialogue.

Regardless of that, one of your jobs as a writer is to do the unexpected. Seeing a man with a wife in the present and then cutting back 15 years and showing the two of them together again – what’s the point of that? If you’re going to flash back, you need to give us NEW INFORMATION.

What they SHOULD’VE done is have Suzanne walk into the room, look like she’s going to walk up to Jim, but she walks right past him and gives a kiss to… Richard. It’s there we learn that Suzanne used to be Richard’s girlfriend. We would eventually learn that she was sleeping with Jim while she was with Richard, and that’s the reason the band broke up.

Now, not only does that scene have a reason to exist. But you have some MAJOR CONFLICT to settle in the present-day storyline, and you build that darker edgier comedy out of that conflict, instead of going to the kid’s swear-joke well.

I’m probably being hard on this because I really don’t like family comedy. But I still think this could’ve been a lot better.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t say “no” to your characters just because a screenwriting website told you to. Every “no” you insert should be believably motivated by the characters and the situation.