I’m always on the lookout for the next big thing.

What’s coming around the corner that has the potential to be a new outlet for screenwriters?

Lots of people have been talking about virtual reality as the next big thing. I think that’s – pardon the language, but – bullshit. We’re 25 years out from those first rudimentary VR demonstrations and many of the same problems exist.

Here’s what I think the next potential REALISTIC avenue for screenwriters is: PODCASTS

I’m not talking about podcasts ABOUT screenwriting. I’m talking about using podcasts as a fictional storytelling medium. Because here’s the biggest problem facing screenwriters as I see it: IT’S HARD TO GET NOTICED. You somehow have to convince somebody that your words on a page – WORDS ON A PAGE! – are good enough to buy, to invest tens of millions of dollars in, to spend the next five years of your life with. This is why everyone chooses intellectual property over words on a page. Seeing that something has worked in a previous medium is a nice insurance package in a business which is, at its heart, a gamble.

This is why I tell screenwriters that if you’re at all interested in directing, direct your own script. It is, bar none, the fastest way to establish yourself in this business. You don’t have to wait for person after person to approve your script until it gets to the last guy on the chain, two years after you started sending it out in the first place, to get that, “Sure, yeah, okay.”

Instead, you become your own personal greenlight. No yeses required.

Unfortunately, the barrier for entry in filmmaking is high. It’s expensive as hell to make a film. Even if you wanted to direct your own stuff, you’d have to raise the money to do so. Seeing stories like this guy’s doesn’t exactly instill confidence in the process.

That’s what I like about this podcasting idea. The barrier for entry is INSANELY LOW. All you need is a script, a microphone, a few actors, and you’re in.

But what I really like about podcasting is that nobody has cracked the fiction space yet. There hasn’t been a “Serial.” And Serial should be great motivation. While everyone else in the podcast space was interviewing D-list celebrities, Serial came up with something that wasn’t just unique, it inspired an entire genre on the format. You can’t kick a stone these days without hitting a true crime podcast.

This means that whoever cracks fictional podcasting first? Becomes a sensation. You get all the press. All the adulation. Everyone loves the pioneer, the guy or gal who managed to open the pickle jar. And because of this, I guarantee. GUARANTEE. That whoever creates that first breakout hit, gets a movie deal out of it. That’s something to keep in mind. Everyone in Hollywood wants stuff based on IP.

Well, once you produce your podcast, you’ve got your IP.

Don’t get me wrong, there have been some attempts at fictional podcasts. High profile even. Believe it or not, there’s a fictional podcast out there with Oscar Isaac playing one of the leads. It’s called Homecoming. Unfortunately, it’s bad. And I’m not surprised. This is a new medium, which means there are going to have to be some stumbles before somebody learns how to sprint. But to show you how desperate people are for this medium to produce something, even that show managed to get an Amazon order for its next season.

The question then becomes, how do you write for a fictional podcast? Well, I think we can look at the failure of Homecoming to see how NOT to write one. Homecoming is billed as a “conspiracy thriller” and formats itself similar to a TV show you might find on AMC. And therein lies the problem. Podcasts are not TV. Whenever you’re writing for a medium, you have to ask, “What are the strengths and weaknesses of this medium?” In writing a play, for example, you have a limited number of characters and a limited number of locations. So a lot of emphasis is placed on dialogue. In film, however, which is a more visual medium, you try and convey things through what the audience can see as opposed to hear.

Since nobody’s written a great fictional podcast show yet, we don’t know the answer to what works and what doesn’t. But that’s the exciting part. You can be creative. You can try things. You can, for example, set up a “faux interview-type podcast” that, on the surface, feels like every other podcast out there, then spin it into a horror film when something goes wrong during a recording session. Ironically, your best bet may be to go back to the old radio days to find inspiration. Remember that one of the most famous figures in Hollywood history, Orson Welles, became famous for his radio telecast of the War of the Worlds. And that was just a guy talking.

By the way, I’m not saying you can’t tell a traditional story on a podcast. Good stories will work on any medium. I’m just thinking that to get that media buzz, the first breakthrough fictional podcast will need to be inventive in some way. Maybe each podcast is a series of interviews from old tapes found in a psychiatric ward. No context given. Each conversation gets progressively freakier. That’s off the top of my head and probably too obvious of an idea. But hopefully it gets the creative juices flowing.

My point is that you could have something WRITTEN and PRODUCED for the world to experience in… less than a week. That’s how low the barrier for entry is here. So, if this interests you, start kicking around some ideas in the comments section. Brainstorm. Maybe a few of you can work together to create something awesome. I’d rather it be a Scriptshadow reader who makes the big podcast breakthrough than some rando. Let’s get to it!

Genre: Drama

Premise: A former Navy SEAL and his retired combat dog attempt to return to civilization after a catastrophic accident deep in the Alaskan wilderness.

About: Today’s script comes from Cameron Alexander. It finished on last year’s Black List with 9 votes. The script sold to the producer of Beasts of No Nation, who, I guess, is cornering the market on scripts with ‘beast’ in the title. This is not Alexander’s first sale. He also sold a sci-fi spec back in 2013 called Omega Point. Alexander used to hang out on these boards before his success. Great motivation for those of you wondering when your shot is coming. :)

Writer: Cameron Alexander

Details: 100 pages

If you’re having trouble keeping your writing lean, stop what you’re doing right now and read this script. It’s a great example of lean to-the-point writing that isn’t SO lean that it lacks substance.

One of you brought up in the comments section the other day that producers only wanted to read super-lean screenplays, scripts they could shoot through in 30 minutes. I don’t think that’s true. One look at the Black List and you’ll see that there’s all sorts of writing.

Also, a good writer can make a dense story read lightning fast while a bad writer can make a balls-to-the-wall thriller read like molasses. In the end, it’s the writer’s skill that matters most.

With that said, when it comes to screenwriting, you should always err on the side of less, not more. And today’s script is perfect for getting you into that mindset. Let’s take a look.

James is a former Navy SEAL who’s had such a rough go of it that all he wants to do is get away. So he straps his combat dog, Odin, into his Cessna, and flies off to the last place in America totally free of people – Alaska.

These two frazzled vets can’t knock the military out of them. They still look around every corner as if it’s a potential threat. But, for the most part, they’re happy. They catch a couple of salmon, drink a couple of beers (well, James does anyway) and celebrate the last great frontier.

The next morning, after they hop in the Cessna and lift off, James starts feeling a pain in his arm. The pain gets more intense until he realizes what it is – A HEART ATTACK. James does his best to fight through it before falling on the yoke, sending the plane down.

The plane crashes into a lake, Odin is thrown into the forest, and James only barely makes it out alive. Convinced Odin is dead, James is ecstatic to find that he’s hanging on. James knows that he must quickly build shelter from the cold or the two will die, a task complicated by the fact that if he works too intensely, he’ll have another heart attack.

The two make it through the night. But now the real shit begins. James looks at his Alaska map to find that they’re 50+ miles from the nearest highway. They will need to traverse difficult terrain on limited rations, both in sub-optimal health, if they’re going to see anything other than pine trees and mountain tops again. Let the journey begin.

As a writer, I’m terrified of these premises. When all you have is one person and a basic survival story, there aren’t a whole lot of things to draw from that the average audience member hasn’t seen before. In Cast Away, you had the added hook of a deserted island and the help of the FedEx boxes. In The Martian, you had Mars. Here, you have trees and bears. Not to mention, you’re competing against movies with 50 superheroes in them.

So how do you combat that? Well, you start by asking what you can give the audience that movies like The Avengers can’t. You don’t have gimmicks. But you do have universal themes. Love. Survival. Never giving up. So you lean into those. There’s never going to be a moment as heartfelt in Avengers: Infinity War, for example, as the moment James realizes Odin is still alive after the plane crash.

Here’s a screenwriting trick that everyone should keep in the back of their mind. We’re always going to root more for somebody if there’s another character who loves them. The reason for this is that we see the character through that second character’s eyes. So we don’t just see James. We see James through the eyes of this dog who loves him more than anything. And vice versa. If either one of these two die, it’s not that we ourselves will be sad. We’ve only known these characters for 80 minutes. It’s that we’ll be sad for the character who lost them, since they’ve known them their whole life.

With that said, as I was reading through Heart of the Beast, I kept saying to myself, “This isn’t enough. This isn’t enough.” Audiences these days have so many options. How is a movie about a guy and a dog walking through Alaska going to compete?

And then I read the ending.

Holy. Shit.

Wow. Right after I read it, I knew: OHHHHH! THIS is why this sold.

It was no longer even a question.

If you’re interested in what that ending is, I beg of you not to jump right to it. It’s NOT a fancy twist ending. It’s just an intense one. And it only works if you’ve read the script all the way through. Which isn’t a chore at all. This script is one of the faster reads you’ll read this year.

Check it out and share your thoughts in the comments.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In any sort of survival story, you want to CONSTANTLY THROW OBSTACLES in your hero’s way and CONTINUALLY REINFORCE THAT THE JOURNEY IS IMPOSSIBLE. If you nail those two things, we’ll stay riveted.

Genre: TV Pilot – Period

Premise: At the beginning of the 17th century, an English sailor washes up on the shores of Japan, which is on the verge of civil war.

About: Shogun was written in 1970 and was turned into a mini-series in 1980. A new version of the show has been off and on in development since 2010. More recently, after the success of Game of Thrones, FX has decided to take a crack at it. Today’s screenwriter, Ronan Bennett, has a bit of a controversial past. He’s endured two stints in prison for participating in a Republican Army bank robbery, although it was ultimately decided that he was wrongly convicted.

Writer: Ronan Bennett (based on the novel by James Clavell)

Details: 60 pages, April 26, 2017 draft

I’ve tried to read this book several times as it’s one of the highest rated books ever on Amazon. All in all, I’ve foraged through about 200 pages. It’s hard to give those pages a rating. The book’s biggest strength is also its biggest weakness: its obsession with detail.

A good story makes you believe you’re in that time and place, and the level of detail here achieves that, providing a richness and authenticity that even the best historical fiction writers would struggle to match. But the more detail you add, the slower your plot moves, and that was why I could never finish the book. I needed more to happen.

With that said, it’s fertile ground for a TV adaptation. The focus on detail as opposed to plot gives any writer wanting to tackle the material an endless trove of information to build a story around.

And while the lack of fantasy elements may prevent FX from creating what they really want out of Shogun, which is their own Game of Thrones, there are still some cool toys to play with. I mean, who doesn’t like samurais?

So I’m hopeful that a show can be cobbled together out of this. Let’s see if I’m right.

The year is 1600. Englishman John Blackthorne, the pilot of a trade ship, has just washed up on a mysterious foreign shore. Clinging to life, he’s rescued by the locals, who nurse him back to health at a nearby village. When he wakes up, he learns where he is: The Japans.

Blackthorne is shocked. You see, the 1600s were some really rudimentary times in the seafaring trade. Deep sea navigation was near impossible unless you were traveling popular routes like England to France. The Japans were like Atlantis to European sailors. Only a few had ever found it. And even those who had were unconvinced they could find it again.

As soon as Blackthorne can get up, he sets out to find his crew, but learns that this strange land has a set of customs unlike any in Europe. The psychotic leader of the village, Omi, beheads one of his own men right in front of Blackthorne for not bowing low enough. Hmmm, maybe Blackthorne should play it cool until he figures this place out.

Meanwhile, we jump inland where the emperor of Japan, or “The Taiko,” is dying. There are 5 main provinces in Japan at the time, all led by different men. It’s well-known that the Taiko’s death will provoke a war between these provinces to become the next Taiko, so the Taiko invites all these leaders together in the hopes of finding a leader before that happens.

Back at the village, Blackthorne demands to see his crew, who he learns are being held captive in a pit. When he rejoins them, he’s told by the locals that one of them will be killed tonight, and that the group must decide who that’s going to be. There seems to be a complicated past between Blackthorne and his crew built upon this most recent mission. So that conversation is far from a happy one.

While at first we’re rooting for Blackthorne and his crew to escape these strange savage people, we begin to sense that they’re not exactly angels themselves. This leaves us wondering who we should align ourselves with. And where, exactly, all of this is headed.

For bigger pilots, the Shogun formula is a good one. Part of the pilot should focus on the smaller picture and part of it the big picture. There are two main storylines here. The first is Blackthorne and his crew. He’s got to get his crew and get the hell out of this place. The second is the impending death of the Taiko. This entire country is on the verge of war.

Without the bigger picture (the Taiko), you don’t feel like the smaller picture matters as much. Not only that, but the big picture lets us know there’s tons of ground to cover, that this is an actual SHOW. I read too many pilots so small in scope that you wonder how they’re going to get past episode 5. I mean, we meet the leaders of all five provinces in Shogun. The places we can potentially go and people we can potentially meet in those provinces is endless.

Shogun also institutes another popular format for shows like these. A leader is about to die. Who’s going to take his place? This is the perfect starting point for a TV show for a number of reasons, the most obvious of which is that we know “shit is about to get ugly.” And since human beings can’t look away from ugly, you’re probably going to get lots of people tuning back in to see the ugly. And this isn’t limited to period pieces. This is what they did with Fox’s Empire.

So what about the nuts and bolts? What’s good here?

I liked the uncertainty of how dangerous this culture was. It added an extra level of tension to every scene. Once Blackthorne sees that you can be killed on the spot for something as trivial as an improper bow, he knows that every interaction going forward will be a tightrope walk. And that’s a dream scenario for a screenwriter. You’re always looking to infuse scenes with tension and conflict beyond the obvious. And that’s exactly what this does.

I also liked the mystery behind Blackthorne’s crew. I don’t remember how they handled this in the book. But here they set it up that Blackthorne presents himself as a trader, but the truth is he may be a pirate. We get these quick flashbacks where his crew is pillaging a wedding. This makes us wonder who these guys really are. And you need a few big questions like that leaving the pilot. If we feel like we’ve already got all our answers, why do we need to tune in for more?

This is the big difference between feature and TV writing. You need to leave threads open and those threads need to be wrapped in mysteries that are actually intriguing.

What Shogun will have to fight against is its incredibly complex mythology. I didn’t count, but I think there were something like 40 people introduced in this pilot. That’s a little less than 1 character per page. Ouch. And while I did my best to summarize the Taiko situation above, the truth is it was so complicated that I could only bastardize the summary. Will audiences be patient enough to sit through all that? Or will they find it to be too specific?

As producer-ish as this note sounds, I’d focus more on samurais and violence, at least early on. Pull people in AND THEN hit them with the intricacies of your mythology. Bore then early and often and they may not stick around for the good stuff.

I liked this pilot. It’s slow. But you can tell there’s many avenues to explore. With that said, I’m wondering if it has the WOW-factor. There are plenty of shows that succeed without the WOW-factor. But it sure makes things easier when you’ve got it. And I’m not convinced Shogun does. We’ll have to see.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The “choose who dies” scene. This scene ALWAYS WORKS. Always. Every time. You put your characters in a situation where they have to choose between themselves which of them must die and it’s always interesting. In this case, the crew must choose someone to be handed to the Japanese for sacrifice.

It’s been months. But a new script has joined the Scriptshadow Top 25!!!

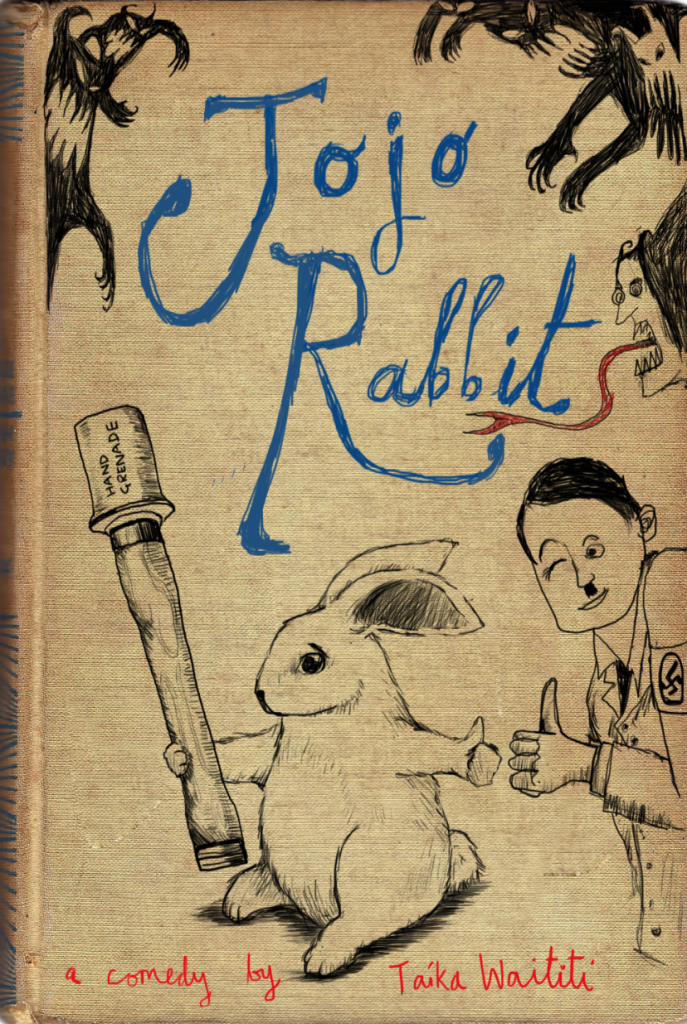

Genre: Comedy

Premise: In 1944, a 10-year old Hitler fanatic whose only goal in life is to become the best Nazi he can possibly be, discovers a secret in his home that will challenge everything he was brought up to believe.

About: Taika Waititi is using the buzz from his Thor film to make his passion project, a comedy about Hitler.

Writer: Taika Waititi

Details: 114 pages

I was hoping Taika was going to join the Star Wars ranks and make a Yoda movie. But after reading this script, I’m glad he’s not. Well, I still want him to make a Yoda movie. But when you’ve got a script that has the potential to become an all-time classic, you put everything else aside.

And we should thank the success of Thor for allowing this to happen. I’m guessing securing funding for a comedic Hitler period piece was tough before having an 850 million dollar grossing film on your resume.

I’ve been hyping this script for the past 12 hours. Let’s find out what it’s about.

The year is 1944 and 10 year-old German, Jojo, has just joined the Hitler Youth. There’s no one who wants to kill Jews more than this guy, who lets that be known to everyone who’ll listen. It’s actually starting to freak people out. One day in Nazi class, Jojo is presented with his first chance to kill something – a rabbit – but he chickens out, which leads to him losing the respect of his classmates.

Luckily for Jojo, he’s got Hitler. Or, a 10 year old’s imaginary friend version of Hitler, a goofy jovial man who wants nothing more than for Jojo to succeed. He encourages Jojo to make an impression in his next class to show that he’s no wimp. Jojo does just that, grabbing a grenade during weapons training and throwing it at a pretend Jewish adversary. The grenade bounces off a tree, lands several feet from him, and blows up.

After Jojo’s loving and awesome mother nurses him back to health, Jojo’s bummed out to learn that he has a permanently scarred face and limp. That’s okay though, because Jojo hobbles back to Hitler Youth the second he can crawl out of bed, determined to become the best Jew-killing machine a 10 year old can be.

(spoilers) Then one day everything changes. Jojo comes home early and hears something upstairs. He runs into his sister’s old room (who died years ago from influenza) and discovers a hidden door in the wall. He opens it up to find Elsa, a 15 year old Jewish girl who, it turns out, his mother has been hiding here.

Jojo’s world is rocked. He considers telling his instructors, but learns that if anyone is found harboring Jews, they will be killed. Jojo consults Hitler about the matter and decides that this is a rare opportunity to learn about Jews. Maybe, if he can learn enough, he can pass that intel on to his instructors, win a medal, and maybe even meet the Fuhrer himself.

Elsa isn’t an easy case study though. As Jojo asks her details about the things he learned in school (Why do Jews suck blood? Where is their hive?) she sarcastically messes with him, confirming some ridiculous assumptions, exaggerating others. It’s only after awhile that he realizes she’s playing with him. And while he really really wants to to make her pay, the truth is that he’s falling in love with her.

Meanwhile, the war is coming to an end. Yet even with the threat of Germany losing, Jojo is determined to stand tall and be the best Nazi he can possibly be. That is until something unthinkable happens, something that will leave Elsa as the only person he can trust in the world. But can Jojo do that? Can he trust his life to the very person he’s dedicated his life to killing?

When we talk about scripts that REALLY stand out, they tend to meet two criteria.

1) The writer has an original voice.

2) The writer takes chances.

Which is exactly what you see in JoJo Rabbit.

“Voice,” remember, is how one sees the world. A writer with a unique voice sees things a little differently than everyone else. They’re showing us the same things we all see. They’re just doing it through a different lens. I mean, we’ve got 10 year old kids exchanging lines like, “Hey, Jews sound scary, huh?” “Yeah, I didn’t know they stole the white skins of Aryans so they could blend in. Savages!”

If Waititi would’ve depended solely on his voice, he’d still have a great script. But he takes a big chance as well. He makes Hitler a character. And not just any Hitler. An “imaginary friend” goofball version of Hitler. I’ve never seen anything like this. And it’s something that could’ve gone very wrong very fast. This is why most writers avoid taking these types of risks. They’re wild-cards that, if played a shade too light or a shade too dark, can end up being disastrous, laughable even.

Jojo Rabbit also includes a longstanding tip I harp on all the time – irony. This is a COMEDY about Nazis. No, it’s not the first time that’s been done. But that contrast – that battle going on between two things that aren’t supposed to go together – creates conflict on the page, leading to an energy you don’t get in most scripts.

It helps that the story is anchored by such a likable main character. And that wasn’t a given. Jojo says some pretty terrible things throughout this movie. But Waititi offsets that by going Screenwriter Old School and including a Save The Cat moment with the rabbit. We know when Jojo refuses to kill that cute little furry animal that he’s a good guy at heart. He’s just been brainwashed.

Then there’s Elsa. You could’ve gone so many ways with this character. Most writers would’ve made her a victim. Sad. Complaining about her miserable life. A downer. Not only is that on-the-nose, but just thinking about that version of the character makes me want to kill myself. That’s a tool more writers need to utilize. When you’re coming up with a character, ask, “How does this character make me feel?” If you’re annoyed, depressed by, or hate them, you probably shouldn’t write the character that way. Making Elsa sarcastic, having her mess with Jojo, stayed true to the spirit of the situation, but also made the character fun.

Halfway into this script, I knew that I was going to give it an “impressive.” But then came the scene that elevated it into the Top 25. **MAJOR SPOILER** If you’re going to write a Top 25 script, you need a scene that makes the reader cry. Or at the very least a moment that profoundly moves the reader. That moment came here when Jojo’s mom is not just killed. But hanged. And the reason we don’t expect it is because the entire movie has been funny. Waititi lured everyone into a sense of security. So when it happened, it hit us like a ton bricks. It was devastating. Seriously. They’re going to need to pass out kleenex boxes before the film and say, “For the 1 hour 20 minute mark.”

But here’s something important to remember for aspiring screenwriters. This shocking moment DIDN’T COME OUT OF NOWHERE. In fact, as soon as it happened, I remembered five separate SET-UPS for this payoff. That’s the thing about shocking twists. You can’t just throw them in out of nowhere or it feels like a cheat. You have to slyly set them up. And the bigger the twist is – killing off a mother late in a comedy is a humongous twist – the more you have to set it up.

Finally, I would encourage all of you to seek this script out for the dialogue alone. The dialogue is creative. The larger-than-life characters are all dialogue-friendly (particularly Hitler). There’s inherent conflict between the key characters (JoJo and Elsa) which always leads to good dialogue. The dialogue pushes the envelope at times, which is important for comedic dialogue. It’s really good stuff.

The ONLY thing that keeps this script from becoming legendary is the ending-ending. I felt like it could have had a bit more punch. Hopefully Waititi shoots a couple of endings here to see what plays best. But whatever happens, this is the kind of screenwriting we should all aspire to.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive ****TOP 25 SCRIPT****

[ ] genius

What I learned: Sarcasm is one of the easiest ways to add life to dialogue. Without it, you have a literal conversation. And being literal is almost always boring. For example, here’s a scene where Elsa “lets Jojo in” on Jewish secrets.

ELSA

Anyway, these days we live among normal humans but often we will take over a house and hang from the ceiling when we sleep, like bats. Oh, one interesting thing is that we can read each others’ minds.

JOJO

Everyone’s minds? What about German minds?

ELSA

No, they are too thick for us to penetrate. We can only read Jewish thoughts.

JOJO

So you’re weaker when you’re separated from your hive…

ELSA

Exactly.

That’s so much better than:

ELSA

You don’t believe this stuff do you?

JOJO

Of course. They taught it to us in school.

ELSA

Do you really think they’re going to tell you the truth about us?

JOJO

Why wouldn’t they?

ELSA

Because they want you to hate us.

It’s fine but literal dialogue is so much drier. You can’t argue that the sarcasm livens things up.

Genre: Action/Thriller

Premise: On a safari trip, a family are driven off-road by rhino poachers and forced to survive a harrowing night in the bush.

Why You Should Read: In 2017, a reported 1,028 rhinos were poached in South Africa. At this current rate, wildlife experts warn that rhinos may become extinct as early as 2020. About me, I’ve been a dedicated screenwriter for over six years and like the majority on this site are determined to move to the next level. “Night of Game” is a unique concept with high stakes, emotional conflict, and bloodthirsty action within an urgent timeline. It’s a movie that will spread awareness of the barbaric act of poaching horn to sell to China and Vietnam. I’m truly passionate about the cause and hope that Carson and the scriptshadow faithful can help this scripts journey to the silver screen.

Writer: It’s a Mystery

Details: 113 pages

Ava DuVernay gets a DC movie nobody’s ever heard of and the INTERNET EXPLODES. While everyone else debates whether film geeks are racist, here’s the question I want answered. Why did Disney let DuVernay go? If you like someone and what they’re doing, you wrap them up. You keep them in the company fold. For Disney to let her flee says loads.

You may think the answer is Wrinkle’s box office. But these deals take time. This DC thing was put together awhile ago. Which implies Disney knew they were dealing with a stinker and were more than happy to let Ava exit. DC, meanwhile, probably signed DuVernay during that 1 month “Ava DuVernay is the greatest filmmaker of our generation” tour. So will DC now have buyer’s remorse? Will box office hindsight lead to a text break-up? This is more dramatic that anything in a Wrinkle in Time so I can’t wait to see what happens next.

On to today’s AMATEUR OFFERINGS WINNER…. Night of Game! No, this is not a sequel to Game Night.

First impressions after reading the logline? This could be a movie. That’s the first question you need to ask with every concept: Is this an actual movie idea? And I believe it is. Sort of a real-life version of Jurassic Park.

But skimming through the comments section, I saw a lot of, “The writing’s not very good here.” The writing’s not very good yet it won Amateur Offerings in a landslide?? What’s going on? I must find out.

20-something Miles Abbot is on vacation in South Africa with his family. He’s with his mother, Lori, his cute 11 year old sister, Caitlyn, and I think his dad. Though that’s up for debate for reasons I’ll get into later.

The three (four?) of them decide to take a safari ride to see all the wild animals. They meet up with a group of tourists which include the hot Anna, her dick boyfriend, Logan, an older couple, and Barry, their driver.

The safari seems to be going well until they’re attacked by an elephant. Luckily, they get away. But moments later, they’re attacked by the most dangerous animal of all – PEOPLE. Poachers to be exact. Miles’s father is shot and killed, even though I was never clear he was with them in the first place, and soon after, Miles gets split up from Caitlyn and Lori.

It turns out the poachers are trying to slaughter a group of rare white rhinos. It just so happens that on the night of their big poach, these tourists got in the way.

While Miles tries to avoid getting eaten by lions, tigers, and bears, he eventually teams up with his crush, Anna, who was somewhere else for some reason. He recruits her to help him find his mother and sister and she’s game. But in the meantime, THEY’RE GAME – as in game for the poachers who can’t leave any witnesses behind.

This script should’ve worked. The core elements are sound. Characters have to survive a night in the bush with deadly animals all around them. AND we have a Taken-like goal of saving a mother and a sister.

So where does it go wrong?

Well, first of all, I had no idea who this family was. I didn’t know why they were in South Africa. I didn’t know what their normal lives were like. I didn’t know why there was this random 14 year gap between siblings. You don’t just throw that in there and not explain it. The most I could gather was that they were a rich entitled bored family with houses on multiple continents. Why am I rooting for people like that exactly?

That’s not to say audiences can’t root for rich people. But you need to then give us a reason to root for them if the first image you give us is that they don’t have a care in the world.

But there’s a bigger issue here. How you set up your core group of characters will determine EVERYTHING that happens after. Cause if we don’t know the characters, understand the characters, sympathize with them on some level, like them on some level, then we won’t care what happens to them on page 40, or 60, or 80.

Therefore it doesn’t matter how dire of a situation you place them in. We never gave a shit about them in the first place. So the first change that needs to be made is an entire backstory needs to be written for this family. We need way more information about them and why they’re here. Also, add some texture to the family dynamic. Right now, it’s so generic.

Off the top of my head, maybe the mom died recently. The dad took the kids here to get their minds off their mom. Miles suggests to Caitlyn, who’s taking mom’s death really hard, that they go on the safari. She’s reluctant but agrees. It’s a chance to heal. At least now you have some history with the family – something they have to overcome.

This leads us to the bizarrely over-complicated plot. You had these poachers who wanted the white rhinos. You had a break within the ranks of the rhino poachers. You had a random local female getting kidnapped. You had a rival tribe warring with the poachers. What the heck is going on here?? I thought this was supposed to be about a family. Instead, it’s about these poachers.

The lesson here is KEEP THINGS SIMPLE. You hear me talk about it all the time on the site yet writers continue to make the mistake. There are some seasoned PRO-FES-SIONAL screenwriters who can pull off complex plots. But if you’re not yet a professional, keep it simple. All we needed was good guys and bad guys here. We didn’t need Rhino Poaching meets The Godfather. Staying in line with that, I like ONE PERSON being kidnapped. Not two. The sister should be kidnapped. That’s all.

Finally, the writing here was EXTREMELY taxing to read. Every paragraph was 3 lines long. And while I’ve said before that you should limit your paragraphs to no more than 3 lines, that doesn’t mean that every page should be twenty 3-line paragraphs. That’s just a sneaky way of writing one 60-line paragraph.

Vary your paragraph lengths. 2 lines here. 1 line there. 3 lines occasionally. You don’t want to get too predictable or monotonous. But the bigger tip here is to ask if you really need three lines in the first place. In screenwriting, you’re trying to say as much as possible in as few words as possible. Constantly be asking yourself, “Do I really need to include that detail?” Don’t get sloppy and always write the long version.

Here’s an example (this paragraph is three and a half lines long in courier font)

Miles watches Logan act like a monkey, swinging on the tire, then swooping down to give Anna a kiss. Trying to act disapprovingly, she pushes him away. A half-smile appears on her face. He pulls her in close.

You could’ve said this…

Miles watches Logan act like a monkey, swinging on the tire, then swooping down to give Anna a kiss. She playfully pushes him away.

This is the tip of the iceberg. We’ve got Screenwriting 101 problems, such as the writer not even writing in the active voice (in the above example, you’d change the tense of the sentence so that “swinging” would be “swings,” “swooping” would be “swoops”). The script needs a lot of work. But if I could give the writer one piece of advice, it would be to stop making the story so complicated. 3-5 tourists stuck in the bush all night is enough. Stop jumping around to so many locations. Miles has to survive the local animals and get to his sister. That’s what we came to see. We’re not interested in poaching politics.

Script link: Night of Game

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The Wall of Text Loophole – Most of you know that readers hate “walls of texts,” pages full of 6-7 line paragraphs with little-to-no dialogue. They’re script killers. But the loophole to this isn’t to write a page full of 3-4 line paragraphs. It’s still going to look like a wall of text. You should be mixing in 1-2 line paragraphs. And unless you’re writing a silent movie, there should be a good amount of dialogue to even it out.