The winner of last week’s heated Amateur Offerings showdown finally gets its moment in the sun. But as every great tennis playing chimp knows, the sun gets awful hot without sunscreen.

Genre: Monkey Tennis

Premise: After a tragic tennis accident, a failed tennis pro seeks redemption by coaching a talented chimp and entering him in to Wimbledon disguised in a man-suit.

Why You Should Read: This is the greatest monkey tennis story ever told. It’s an ironic homage, a pastiche if you will – a spoof if you must – of the great animal-based comedies of the 90s like Beethoven, Flipper, and Dunston Checks In, each one of them an iconic work which has stood the test of time.

Writers: Chris Grezo & Rupert Knowles

Details: 110 pages

Das.

Chimp.

Chimp.

Das.

By themselves, the above words mean nothing. Invisible food-coloring, if you will.

But together? They represent one of the most powerful phrases in the English language.

Das Chimp.

Don’t believe me? Have you ever had a single passionate thought about the word “Das” before last Friday?

Me neither.

But look at how much controversy that same word created once combined with “chimp.” We had a fellow competitor questioning the sanity of each and every member of the Scriptshadow community when his script was defeated by Das Chimp.

Let us call a spade a spade. “Das Chimp” is the single greatest title to ever grace the pixelbytes of Scriptshadow. It is both simple, yet oh so complex.

And therein lies Das Chimp’s biggest hurdle. Could a title promise something so great, that it was impossible for the story to live up to it?

My friends, I’m ready to find out if you are.

So please, grab a beer, grab a racket, grab your favorite stuffed animal, and join me… for Das Chimp.

It’s never a good day when you kill your doubles partner. That’s what happened to John Protagonist, who lost his nerve when his tennis match got tight, accidentally hitting the chair umpire with a serve, causing a chain reaction of Center Court implosion, leading to a giant light landing on poor Hamish.

Adds a whole new meaning to the term, drop shot.

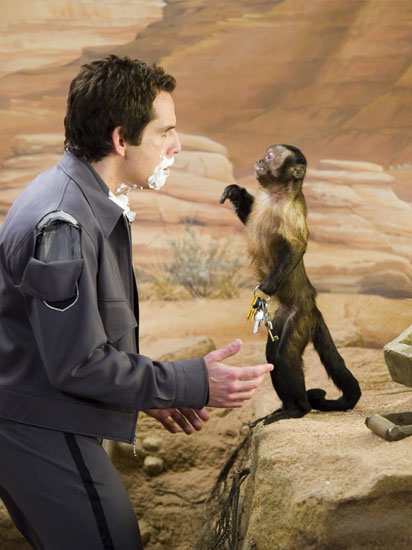

Fast forward 10 years and John faces each day with the regret of what he did to a man who didn’t deserve his demise. John heads to the zoo to share a beer with his custodian best friend, Duncan, when he sees a chimp effortlessly hitting a tennis ball against the wall.

John approaches the chimp’s handler, the excessively weird but beautiful zookeeper, Lily, and asks if he can teach the chimp (Pierre) tennis. Lily is game, but to do this, they’ll need to make sure no one realizes Pierre is gone. John comes up with an idea and puts Duncan in a monkey suit where he’ll stand in for Pierre.

Once John gets Pierre out on the court, he’s even better than he thought, so he starts entering Pierre in tournaments. The scrappy Pierre keeps winning, and actually earns a birth into Wimbledon! There’s only one problem. Monkeys aren’t allowed to play Wimbledon! Who would’ve thought?

So John gets another one of his genius ideas. He’ll dress Pierre up in a human suit. No one will know the difference. Meanwhile, John is dealing with some unexpected issues. Pierre is in love with Lily. And the reason Lily is so weird is because she was raised my meerkats. She has no clue how human interaction works.

But John’s biggest challenge comes when Britain’s #1 Doubles team is mauled by a wild boar. Britain comes to John and asks if he’ll team up with upstart Pierre to represent the country again. John is reluctant, but dons the headband once more, this time to play with a chimp… a chimp wearing a human suit.

Elephant shit.

Oh, I’m sorry. That’s not my assessment of the script.

I’m just noting that when you can include an elephant shit joke in your movie? And it’s FUNNY? By gosh you’ve already succeeded my friend.

But Das Chimp is no flash in the pan one-elephant-shit-joke wonder. Believe it or not, the majority of this script is funny. And not just funny, but well structured!

There’s an easy way to distinguish between “I don’t know how to write a screenplay” broad comedy and “I actually know what I’m doing here” broad comedy. Setups and payoffs. When I see lots of setups and payoffs in a broad comedy script, I know the writer has thought the script through, and, at the very least, completed a few rewrites. You can’t include too many payoffs without going through the script and figuring out where to set up them up.

For example, the crazed always angry Zoo owner lets out one of his wild boars at night to take care of people sneaking into the zoo after closing. 50 pages later, that same boar is responsible for sending John back into competition, after it mauls the other British doubles team.

And Lily is an entire compilation of setups. She acts beyond bizarre, to the point where you wonder if she’s retarded. Then we learn why she acts that way. She was abandoned by her parents as a kid and raised by meerkats. She would then get a job at the zoo because animals were the only world she understood.

But the best thing about Das Chimp is that Grezo and Knowles rarely make a lazy choice. Everything that happens here is either bizarre or the result of something bizarre.

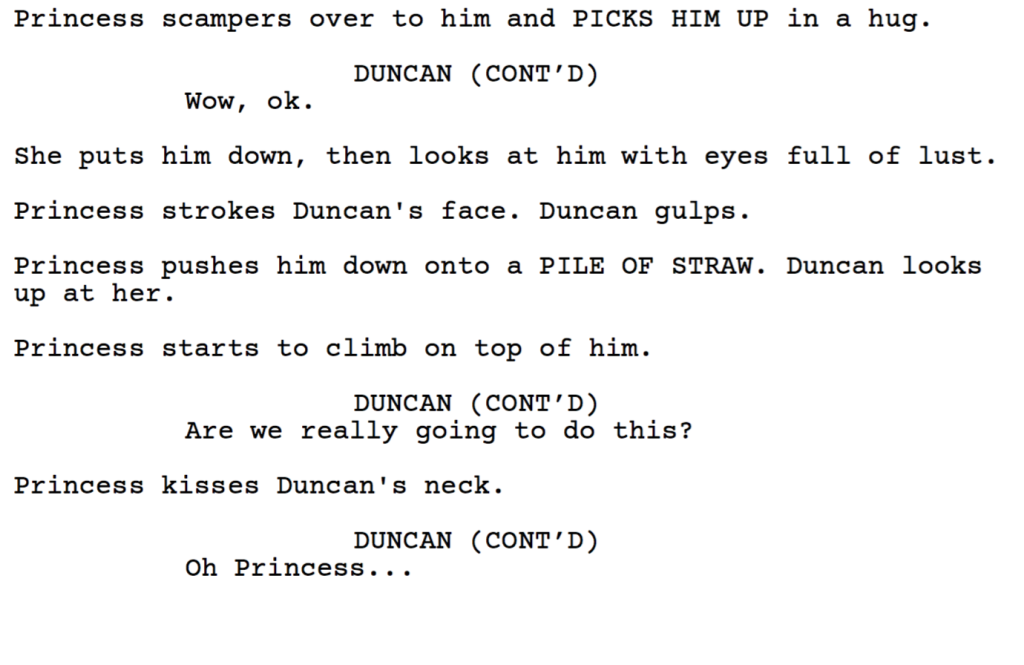

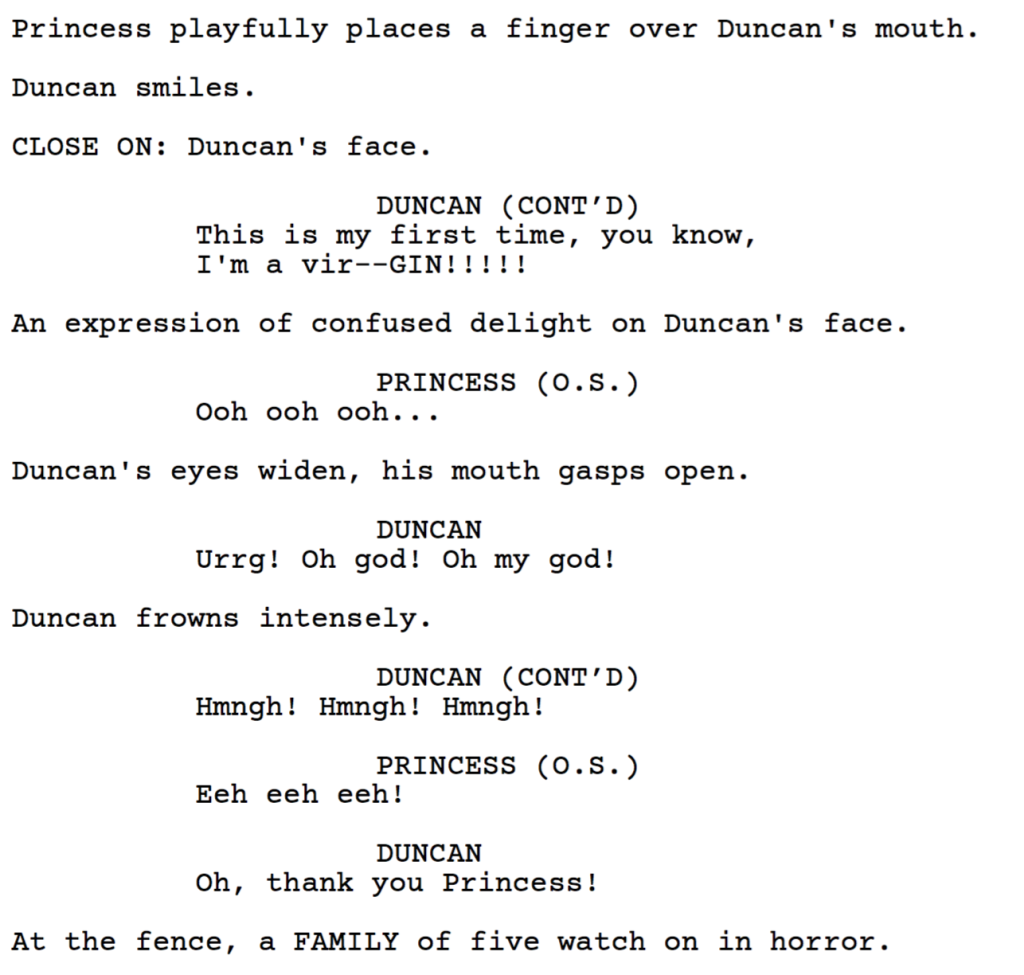

I have no doubt that a less talented writer would’ve made Duncan (John’s friend) some corporate type, so as to properly contrast the friends’ lives (like the screenwriting books tell you to do). Instead, they make Duncan an animal shit-shoveler over at the zoo. And thank God they did. Duncan’s storyline – while in chimp costume, he falls in love with a real chimp, Princess – was my favorite of the script, and led to the biggest laugh.

In this scene, Duncan comes to talk to Princess. I dare you to read what happens next.

If I have a beef with the script, it’s that the setup could be sharper. Pierre’s ascent from chimp who likes to hit against the wall to rising tennis star is way too fast. I understand that we have to get to the story, but I never understand why it was so important that Pierre start playing tournaments. John’s motivation seems more tied to using Pierre as an excuse to be around Lily. He didn’t need to enter Pierre in tournaments to do that.

This may seem like nitpicking. But the script ends up taking its plot surprisingly seriously later on, retroactively sending me back to this first act, where the only reason things seem to be happening is because they need to for the script to exist.

Another area that could’ve been better is the Pierre tennis matches, which were too repetitive. A lot of Pierre running around for balls it doesn’t look like he’s going to get to… and then he gets to them! I speak from experience as I’ve written several tennis scripts myself. I’ve learned you need to limit the repetitive actions of the sport and focus instead on individualized non-playing situations.

For example, instead of writing an entire page of, “… and then Pierre runs over to get the ball, barely reaching it – BAM! – he hits it back…” you might focus on the fact that a ballboy suspects that Pierre isn’t human, and write in a series of moments where the ballboy is trying to figure it out.

Obviously, you have to include SOME points to build the drama in the match. But the strange thing about screenwriting and sports is you want to include as little actual playing of the sport as you can get away with. The exception would be if you’re focusing on something unique within the game. For example, if John’s racket cracks during a point and he doesn’t have a backup, so John needs to play a point WITHOUT A RACKET. We’re going to be more interested in that point because it’s unique. It’s not another, “…he reaches for the ball with all his might…”

Das Chimp isn’t perfect. But these two writers are DEFINITELY funny. I believe it’s a script worth perfecting. So I’d encourage anyone here that if they can think of more funny scenes for Das Chimp, to share them with the writers. The more laughs we can pack into this script, the better shot it has.

Script link: Das Chimp

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Give friends and family jobs that keep them closer to the story as opposed to further away. So you don’t want to make Duncan an architect or a stock trader. You give him a position at the zoo, where we can keep him close to the story without having to force it.

So the other day I FINALLY decided to watch “Atlanta,” the show from Community alum Donald Glover that had gone on to win a Golden Globe for Best Television Show, a Writers Guild Award for best Comedy Series, and was nominated for an Emmy in writing. Personally, I thought it looked pretentious and unfocused, so I never got around to watching it. Until now.

Before I get into my thoughts on the series, I have to share something with you. I hate Donald Glover. There’s something about the guy that rubs me like a bad batch of poison ivy. Discounting the fact that he’s an egomaniac who must prove he can act, direct, write, produce, rap, and do stand-up comedy, all under the guise of an “aw-shucks-I’m-just-trying-to-work” persona. Discounting the fact that there are articles being written about him that tell everyone to “underestimate Donald Glover at your own peril” (Gag me with an Instagram like). There are things even beyond those issues that I despise.

Mainly, that his writing is just okay. His dialogue is decent at times. But his storytelling leaves a lot to be desired. And his acting vacillates between mini mumbling monologues and looking like he’s so stoned that he might fall asleep at any moment.

Worst of all, it’s impossible not to know you’re watching Donald Glover whenever he’s onscreen. The Martian basically stopped for 5 minutes mid-film so that they could include a random “Donald Glover Short Film” Scene. I thought an actor’s job was to disappear into a role. Glover goes in the opposite direction, always wearing the same hipster clothes, always sporting the same trendy haircut, always giving the camera the same Donald Glover hangdog expression.

Which makes it all the more perplexing that the man is one of Hollywood’s fastest rising stars. And it really bothers me. Not because I don’t get the love for the dude. But because every time a writer or an actor or a director (or in Donald’s case, an actor/writer/director/producer/rapper/caterer/surgeon) rises up, Hollywood is telling you something: THIS IS WHAT WE WANT. Which means you, the aspiring multi-hyphenate, must understand why this person is ascending so that you can take some lessons from it and use them to further your own career.

Yet here I stood with Glover, unable to figure out how he’d separated himself from the pack.

I’m sure Glover’s old fellow staff writers on 30 Rock (where he started) are asking the same thing. Why is this guy blowing up while we’re still trying to get staff writing jobs on The Goldbergs?

Powering down my television after that decidedly average pilot episode of Atlanta, I finally figured it out.

Do you want to know what it is?

Voice.

What Donald Glover has that all those other staff writers and bottom feeder feature assignment writers and aspiring amateur screenwriters don’t have is a VOICE. It’s undeniable. Glover is bringing something unique to the table that nobody else out there is doing. I don’t know what it is, exactly. But I do know that when I watch his shows or listen to the dialogue he’s written? It’s different. And the reason this is so important is that VOICE is the equivalent of GOLD in the artistic community – the most valuable commodity there is – to the point where it can propel someone like Glover to stardom.

Think about it. How many people in this business truly have a unique voice? Very few. The majority of Hollywood’s army are cogs in a machine, regurgitating or helping to regurgitate the same old movies and TV shows over and over and over again.

When someone emerges from that glut of sameness to give us something unique, they stand out like a punch at a cuddle party. In fact, the very reason I hate this guy is tied to his voice. That’s what voice does. Its unique point-of-view incites passion one way or another. In my case, it’s “or another” but for a ton of people, it’s “one way.” He’s got something unique.

As artists, there is no bigger fear than being bland. Wondering whether we’re one of those also-rans who doesn’t have anything original to say keeps us up at night. Don’t get me wrong. You can still work in Hollywood without a voice. If you can perfect form and technique and craft and understand how the storytelling and character creation mechanisms work, you can work in this town. But you’ll never be special. You’ll never stand out like Donald Glover.

So today, I’m going to help you find your inner voice. The bad news is, voice isn’t something you can construct through pure force of will. Your voice is who you are at your core and therefore emerges naturally. When you look at someone like Bill Murray, his unique persona isn’t calculated. It’s just him. On the flip side, there are clearly celebrities who enhance their voice in a calculated manner. Lady Gaga, for example, does a lot of calculated things in order to enhance her “voice.”

With that in mind, here are seven things you can do to find your voice so you can be more like Donald Glover and less like those journeyman staff writers on The Goldbergs.

1) Identify what your world view is – What is the operating thesis by which you see the world? Is it John Lennon-esque, that everyone should put aside their differences, hold hands, and find peace with one another? Or is it Machiavellian, where everyone’s backstabbing each other and looking out for number 1? Is it idealistic, like Spielberg? Or is it fatalistic, like Kubrick? One of the key reasons for a writer lacking voice is that they don’t explore underlying themes in their work. Without a point-of-view, a lot of what we write is empty.

2) Write stories that exploit that world view – A big mistake writers make is not writing the scripts that explore the world view they’re so passionate about! For example, if you have a Kubrickian world view, but you’re writing Das Chimp, you’re not taking advantage of your voice. Every script you write where you’re not exploring your world view is going to feel lacking in some way.

3) Break rules – Following the rules allows you to write something good. But breaking the rules is how you write something great. Writers with voice don’t make sure their inciting incident happens on page 12. They’re too busy telling a unique and unexpected story. There’s a balancing act here. You can’t ignore rules completely. They’re what keep your story focused. But if you come across a rule in regards to your script that, by breaking, makes the story come alive in some way? That’s a sign that the rule is worth breaking. In “Room,” the Screenwriting Rule Nazi would’ve encouraged the writer to either get them out of the room at the end of the first act, giving them enough time to build a storyline post-Room, or in the third act, crafting the escape as the climax (like you’d see in a traditional thriller). Instead they placed the escape at the midpoint, allowing them to explore a devastating question: Where was life better? In the room? Or out?

4) Be raw and honest – To have a voice, you have to let us into your soul. It’s the only way we’re going to get to know the true you. And the deeper down you take us, the more ‘you’ we’re getting. The majority of writers write as fanboys. They re-write their favorite horror movies, reshape their favorite action set-pieces, mimic their favorite dialogue writers. They think that’s writing. That’s not writing. Writing is baring your soul through your characters. Be truthful. Be honest. Get into the nitty gritty of how you endure the human experience. This is why everybody 30 years later is STILL trying to write John Hughes movies and failing. They don’t realize that those movies don’t work because of the fun parts. They work because of the darkness, because of the way Hughes explored human psychology during one of the most confusing times in a person’s life – adolescence.

5) Be brave – Tarantino, one of the most voice-y writers ever, once said (paraphrasing) “You should always be a little nervous to let someone read your stuff because of how fucked up some of it is.” That’s not to say everyone should include a Gimp-Rape scene in their script, especially if you’ve been hired to write The Nut-Job 3 (on second thought…..). But a good writer explores those messy areas in life and in human interaction that aren’t usually talked about openly. Embracing those awkward moments brings truth and originality to your work.

6) Evolve The Genre – We all have our favorite genres to write in. So I’m going to give you advice that’ll place you ahead of 90% of aspiring screenwriters out there. Before you write your script, ask yourself, “How do I plan to update this genre?” If you’re writing a horror film, maybe you’re infusing race into it (Get Out). If you’re writing a heist film, maybe you’re infusing time manipulation into it (Inception). If you’re writing a Western, maybe you’re bringing a level of violence to the proceedings that has never been seen before (Bone Tomahawk). I consider this tip, more than any other, a ‘cheat code’ in the game of voice, because without much work up front, you can make a script feel totally unique.

7) Make sure there’s at least one character in your script who’s unlike anything we’ve ever seen before – Audiences rarely remember the plot to a movie years later. But they always remember the characters. I’ve found that voice-y scripts always have at least one character who’s totally and completely different. Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver. Miles in Sideways. Wade in Deadpool. Juno in Juno. Unique characters go hand in hand with voice. So don’t write your script without one.

8) BONUS! – A non-traditional narrative – I went back and forth on whether to include this tip because there’s nothing more that I hate than a rambling narrative, a vague plot, or unclean structure. But the proof is in the pudding. The artists with the strongest voices tend to sacrifice plot and structure for character and situation. Woody Allen, Quentin Tarantino, Sophia Coppola, Aaron Sorkin, Christopher Nolan. I’m not a fan of this tip. But I can’t deny its presence when it comes to writers with voice.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. All logline consultations come with an 8 hour turnaround. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Hey guys, I’m out of the office today.

But I wanted to leave you with a tip that you can apply to any script on your hard drive RIGHT NOW.

The tip came about after reading a few amateur scripts this week and noticing a number of bad dialogue scenes where the writers were making the same mistake.

One of the things screenwriting books tell you to do is “have more going on in your scene than just dialogue.” So instead of having two characters sit across from each other and talk at the kitchen table, have them talking to each other while they’re doing the dishes. The idea being that now they’re actually “doing something.”

Or move the scene somewhere else entirely – say, to a yoga class! This change in scenery coupled with a few yoga poses will bring the formally boring-ass dialogue to life.

Unfortunately, this is bad advice. All this does – regardless of the fact that yoga pants are the greatest invention of the 21st century – is make the scene more visually interesting. It doesn’t change that your characters are still just talking to each other.

What you want to do instead is create a reason for why the characters are doing something, and for that reason to have some stakes attached to it. By adding importance to the action, a scene with the exact same dialogue actually does come to life.

For example, let’s go back to that kitchen scene. What if we established that our heroine, JANE, has a nasty husband who goes apeshit if the house isn’t sparkling clean when he gets home from work? And he’s going to be home soon. Now, cleaning those dishes takes on a whole new meaning, right? If they’re not clean by the time Psycho Hubby gets back, there will be hell to pay. There are actual stakes attached to getting those dishes done.

Or let’s put Jane back in that yoga class with her friend, KERRY. This time, instead of using yoga as a location to spout off some boring dialogue you’re trying to get in, make it so Jane likes one of the guys in class. And Jane and Kerry map out a plan ahead of time to get his attention. These newfound stakes (trying to get this guy’s attention) give a formally directionless scene purpose.

The cool thing about this device is it improves the dialogue without you even having to change it. Let’s say that kitchen dialogue scene had Jane and Kerry discussing the difficulties of motherhood. Without Pyscho Hubby coming home, the conversation is just that, a conversation. With Psycho Hubby, the same conversation feels like it’s being used to fill in the silence and help alleviate the anxiety both women feel from that looming arrival.

The lesson here is to never have your characters performing random actions or going to random locations in the hopes that that will improve the scene. Create a purpose to the scene that includes stakes so that what the characters do actually matters. Only then will the dialogue come to life.

Genre: Buddy Cop Comedy

Premise: When a reckless cop who made his mark in the drug-fueled 80s is paired with a timid C.S.I. detective who prefers to hide behind his tools, the two must put aside their differences to take down a mysterious Scandinavian drug kingpin.

About: Colin Trevorrow has gone on record as saying this is the most fun he’s ever had writing a script. He and his writing partner on Cocked & Loaded, Derek Connolly, met as interns on SNL ten years prior, and sold the project as a pitch. While the two would each go on to their own solo careers, they continue to collaborate, most recently on the final chapter in the new Star Wars trilogy, Star Wars Episode IX: The Return of Maz Kanata.

Writers: Colin Trevorrow & Derek Connolly

Details: 102 pages (2009 draft)

The buddy cop genre will NEVER DIE!

So stop entertaining those false-ass notions!

This is good news, script homies. Like the rom-com, the zombie flick, and the body swap comedy, there is always an opportunity for someone to come in and find an original take on these sub-genres. Mind you, this is one of the biggest things that separates seasoned writers from beginners. The beginner ALWAYS writes the same versions of these movies that we’ve already seen. The veteran knows the script has NO SHOT unless they find a fresh angle.

For example, a beginner might say, “Female-driven comedies are big right now. What if I do a buddy cop comedy where one female character is white and the other is black!”

Sorry. That’s exactly why you’re still trying to get people to respond to your logline e-mails. That’s only an eensy-teensy-bitsy more original than, say, The Heat. You have to be a lot more original if you want to stand out.

Now, there’s something that happens in this industry that makes the above advice confusing. Every once in awhile, a producer will say, “What if we paired Amy Schumer and Leslie Jones in a buddy cop movie?” And everyone at the studio is like, “Oh my god, great idea! That would be so funny.” The producer then gets a writer, spits out a buddy cop script with a white partner and black partner, recruits Amy and Leslie with offers from the studio, and by the end of the year, they’re shooting.

“I thought you said that idea wasn’t original enough, Carson! Looks like you were wrong!”

First of all, I’m never wrong. Second of all, that situation is not your situation. That situation is a producer with the power to put a movie into production. Your situation is needing to stand out amongst thousands of other screenplays. That’s why your take on an established sub-genre needs to be unique. You’re trying to stand out amongst a sea of people.

Cocked & Loaded begins in the 80s, when cops were men, dammit. 20-something John Brock is living the dream. Not only is he a cop, but he’s partnered with Nick Angelano, the Dirty Harry of 1985. The two are mowing down a bunch of casino thugs, living the cop-thug life, when all of a sudden – BLAM! – Nick Angelano’s head explodes.

Behind it… the hairless Scandinavian known as Veli Verkko. Veli laughs at a stunned Brock before disappearing into the shadows. Brock screams up into the sky, noooooooooooo!

Cut to the present and Brock is still haunted by the loss of his partner. Bitter, hate-filled, repugnant, all Brock cares about is kicking ass and drinking whiskey. Which means he hasn’t changed much.

Across town we meet Glen Choder, crime scene investigator, who’s mapping out the murder of an old woman. Glen is a new breed of cop. Dresses well. Polite as fuck. And not too good with a gun. Which is why he sticks to mapping blood splatter.

I think you know where this is going. When a wealthy lobbyist is murdered, Brock and Choder are paired up to find out who did it! The lobbyist’s murder is a strange one, as it looks like he was injured out on the town, then came back to his hotel room where he bled out.

Choder finds some horse hair on the man and runs it by a local zoologist, who reveals that the hair comes from a rare horse you can’t even find in the United States. When further clues lead our partners to a VIP sex party that our victim used to frequent, things start to get really weird.

And wouldn’t you know it, all those animals and sex lead back to one person: Veli Verkko. With revenge finally within grasp, Brock locks and loads. But he’ll need to get past one last person to avenge his old partner – his new one.

So here’s the deal.

And I want you to write this down if you plan to write a comedy. Hell, write it down regardless of what genre you write in.

Generic concepts LEAD TO generic situations LEAD TO generic jokes.

If you find yourself struggling to write original scenes (or characters or dialogue), a lot of times it has less to do with the actual scenes, and more to do with the concept itself.

You see, when you start with a generic concept, you are laying the groundwork for a bunch of empty bland situations. This happens a lot in comedy sub-genres. You pair up two opposites to play the cops, and you think that’s all you need. The rest will write itself.

But because you’re starting with a base that’s so bland, there’s no soil to generate original ideas. This is why you want to START with as original a concept as you can. The more original it is, the more original the situtions and scenarios will be. You guys have all heard the saying: “It practically wrote itself.” The scripts that do this are scripts that are born out of original ideas.

Look at a script like Das Chimp. For those who missed Amateur Offerings, here’s the logline for the comedy: After a tragic tennis accident, a failed tennis pro seeks redemption by coaching a talented chimp and entering him in to Wimbledon disguised in a man-suit.

Whether you like that idea or not, you can see that because the concept is so original, it can be exploited for a ton of original scenes – scenes that could only exist in Das Chimp. In the opening scene, our protagonist’s doubles’ partner is killed in a tennis accident. You can’t write that scene into your average comedy. It’s specific to Das Chimp.

For me, that’s the primary way I judge comedy. Because when I’m not laughing, I’ve found that it’s often not about the jokes. It’s that the jokes could exist anywhere. They’re not specific to this idea.

Where does that leave Cocked and Loaded?

Well, that’s a good question. The script started off in bland buddy-cop territory. The investigation felt random (a horse hair?) and we’d find ourselves in set-pieces that seemingly had nothing to do with the story (a VIP sex party).

But then the clues started coming together, and we eventually find out (I need you to take a deep breath for this – don’t say I didn’t warn you) that our lobbyist was one of a group of rich men who pay to have rare animals shipped into the United States to have sex with (our victim died of horse-penis insertion). I have to admit, I had not seen that in a script before, so I had to give these guys points for originality.

My problem was more with the lead-up. Despite the plot being original, that’s not the most important thing in a comedy. The most important thing are the characters and the laughs. And this was light on both. Both our heroes were constructed too rigidly out of the Screenwriting 101 mould. They each had these big flaws. And they were both perfect opposites.

And because I didn’t buy into them as real people, I didn’t laugh much at what they said. And if I’m not laughing a lot in a comedy, it’s kinda hard to endorse it.

Maybe I’ll be laughing more this Friday… when I review Das Chimp.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When coming up with a comedy set piece, don’t approach it like, “Ooh, I bet I could find a lot of laughs in this scenario.” Approach it like, “What set-piece could I include that could only happen in this movie?” You’re bound to get a funnier scene out of it. Because, yeah, there are going to be laughs to be had in randomly crazy scenarios (like a sex party). But I promise the laughs will be bigger if the set-pieces are specific to your concept.

Genre: True Story

Premise: When a lawyer is able to defeat Chevron in Ecuadorian court to the tune of 19 billion dollars, Chevron hires the most lethal and dirtiest lawyer money can buy to get the verdict thrown out.

About: This script made last year’s Black List. I believe both Jay Carson and Matt Bai are political correspondents and that this is their first foray into the screenwriting world. They obtained the rights to the 2012 New Yorker article “Reversal of Fortune” by Patrick Radden Keefe, in order to write the script.

Writers: Jay Carson & Matt Bai

Details: 131 pages

It’s important to remember that there was a time in Hollywood when Eddie Murphy was making movies in fat suits that had characters communicating in fart-speak.

I’m sure during those dark hours that every development exec in Hollywood feared the next spec script to land on their desk. Who knows what kind of fat/bodily-function combination they might have to read that day. A talking fat dragon that spoke vomit? A fat grandma who spoke in burps? An insanely obese brain surgeon who spoke in that flapping-your-hand-in-your-underarm noise?

And yet, those days eventually passed.

I have to remind myself of this when I look down at my pile of scripts and see: True story, true story, true story, true story, true story, true story, true story. Sooner or later, Hollywood audiences will get bored of the true-story biopic combo and we’ll be able to read stuff that has some actual, you know, IMAGINATION.

Until then, true stories make up 8 out of the 10 scripts out there. It’s so hard to get excited to review these things cause they’re all the damn same. And that’s the writer’s fault. You guys should know that Hollywood is inundated with these things so if you’re going to write your own true story, it better damn well be different than all the others.

Let’s find out if Donziger is different from all the others.

Steven Donziger has just done the impossible. The 50-something legal ace went down to Ecuador and won the country a 19 billion dollar settlement against Chevron, after the oil giant spent the last 30 years turning the country into a chemical dump.

Donziger heads back home with plans to celebrate. But what he doesn’t know is that David O’Reilly, the CEO of Chevron, has zero plans to pay this dude. He goes out and hires Randy Mastro, a sick-ass laywer with a lethal history of doing whatever it takes to get the job done. O’Reilly wants Mastro to reverse the whole damn judgement.

Mastro shows why he’s nasty right off the bat. Whereas every other Chevron lawyer wants to exploit the impossible-to-prove technicalities of the case (was Chevron ever “really” in Ecuador?), Mastro wants to go after the man himself. If he can convince a judge that Donziger pulled off some bad things during the trial, he could get that verdict reversed.

Mastro keys in on a documentary that Donziger was shooting during the trial and is able to get his hands on all the footage, essentially giving him a behind-the-scenes look at every single thing Donziger did during the trial.

Mastro notices that a mysterious man keeps popping up – a dude named Carlos Bernstain – who may have been a liaison to Donziger pulling some back-door bribes with the Ecuadorian judge. Mastro uses that tidbit to get a judge to enact a Gestapo-esque raid of Donziger’s home, where every one of his family’s computers is taken.

Meanwhile, Donziger refuses to give in. He uses some legal tricks of his own, convincing every country in the world who works with Chevron that, if it meant taking their cash, Chevron would not respect their laws. This causes Chevron stock to plunge and the race for that 19 billion is on. But can Donziger keep it up? Can anyone really defeat a 200 billion dollar company? My man Donny Z’s about to find out.

Make no mistake. This is a documentary. I mean, it’s an article. But it’s really a documentary.

And only certain documentaries can be turned into movies. This is not one of those documentaries. There’s too much legal mumbo-jumbo. There’s too much backstory. The story plays out over too long of a time. These are huge red flags when you’re thinking about adapting an idea into a feature.

I’ll give you an example. We learn the lawsuit is only half against Chevron. The other half is against Texaco, who was the original company that destroyed Ecuador. Chevron only came in later, buying up Texaco, and is being sued for not cleaning up Texaco’s mess. There are a ton of boring details like this that the script is forced to cover.

Since documentaries are, basically, one continuous stream of exposition, nuanced details like the above work great in them. But in feature films, exposition is the enemy. In an ideal script, exposition would be less than 5%. Here, it’s like 30-40% And it’s hard for a movie to gain any momentum when the exposition takes up that amount of time.

Truth be told, exposition is one of the things I hate most about these stories. So much needs to be conveyed before we can start dramatizing the story (that’s a fancy way of saying: before the story can actually be entertaining). And, indeed, I was half-asleep during the first 40 pages of this. It was maddeningly boring.

The script doesn’t pick up until Mastro arrives. It’s strange because the script is titled, “Donziger,” but it should really be titled “Mastro.” He’s the only interesting thing about this. His nasty tactics to reverse this settlement were the only fun the script had. You always wanted to see how nasty he was going to get next.

Also, I’m a big fan of holier than though villains, guys who do terrible things but market it like they’re angels doing the world a favor. I loved how Mastro was destroying a man who was trying to help a country recover from being turned into a cancer-breeding chemical dump, yet he could go on about how his actions were not only moral, but essential to keeping the sanctity of law in tact. At one point he makes an argument that what Donziger did was actually worse than what Chevron did (for those keeping count, Chevron killed thousands of people in Ecuador and left many more with cancer).

Unfortunately, Donziger the character doesn’t become interesting until the last third of the screenplay, when his secrets start to be exposed, and he begins to lose his family due to putting the case before them. I found all of that to be quite good, but giving me a vanilla character for 90 pages and turning him chocolate for the last 40 isn’t going to cut it.

Ultimately, Donziger the script has some good stuff going for it. It explores the moral ground between good and bad and reminds us that gray will always be where the majority of us reside. But I have to give the script a “wasn’t for me.” It’s probably closer to “worth the read” but there are so many scripts in this genre right now that if you can’t give me a true story that stands out in some way, it’s hard to endorse it, well-written or not. One of your jobs as a screenwriter is to be original. Unfortunately, Donziger fails that test badly.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I always love when characters make a point via a good analogy. It’s just a fun way to convey what would otherwise be boring dialogue. So in one of Mastro’s first scenes, he needs to convince O’Reilly to do things his way. This is what he says…

MASTRO: You know why the Yankees win so much?

O’REILLY: Money. Everyone knows that.

MASTRO: It’s what they do with the money. They buy left handed hitting and left handed pitchers. Why?

O’REILLY: Well, that stadium—

MASTRO: Has a short porch in right field. Exactly. They build their team around that field. Always have. Babe Ruth. Reggie Jackson. Whitey Ford.

O’REILLY: OK

MASTRO: When you go into Yankee Stadium, the game is rigged. You think you’re playing the same game as the Yankees, but you’re not. It’s their field and they always have the advantage.

O’REILLY: So you need some lefties of your own, right?

MASTRO: (shaking his head) It’s impractical. You’ll never build as good a team for that ballpark as they have. You want to beat the Yankees, your best shot is to get them in another venue… say Fenway where right field goes on forever.

O’Reilly nods — he gets it.