Genre: Action

Premise: When the United States’ most prominent aircraft carrier is infected by a deadly North Korean biological virus, they must figure out how to stave off both the virus and the North Koreans themselves.

About: This script comes from producer Arnold Kopelson, who was, at one point, one of the top five producers in Hollywood. He gave us such movies as Seven, The Fugitive, Platoon, and The Devil’s Advocate. But nothing is forever in Tinseltown, and Kopelson’s last feature credit was the 2004 Ashley Judd thriller, Twisted. Airborne was supposed to be a comeback project for him. However, the aircraft carrier element might’ve doomed the project, since it was competing, at that time, against the 200 million dollar juggernaut that was Battleship. With the North Korean threat reaching a fever pitch in the news recently, maybe this project gets new legs.

Writer: Jonn Moore

Details: 140 pages – 2008 draft

I wouldn’t call what I’m about to discuss an epidemic. But it’s a big enough problem that I run into it frequently.

That problem is dated writing.

Dated writing is when you write with concepts, characters, plots, and ideas that are tonally consistent with a bygone era.

When someone reads your script, it feels like they’re reading a script from 20 or 30 years ago. Now on some level, it makes sense why this happens. If you’re pursuing screenwriting, the movies that originally made you fall in love with this medium are going to be old, and those movies are always going to influence your writing.

However, if you try and write movies like that today, your scripts, by and large, will feel out of touch.

For example, imagine trying to write E.T. today. Or Richard Donner’s idealistic Superman. Or Pretty Woman. Producers would look at you like you were crazy.

See, this is the big lie writers tell themselves. “Hollywood doesn’t want anything new.” That’s actually ALL Hollywood wants, is the next big new thing. The reason why writers get this wrong is because they don’t understand how Hollywood defines “new.” Hollywood defines new as “a fresh take on an established idea.”

Jordan Peele finding a fresh take on the horror film in Get Out. Wonder Woman’s WW1 setting brought a fresh take to the superhero film. Dunkirk’s dialogue-scarce time-jumping storytelling was a fresh take on the war film. Baby Driver’s musically influenced set-piece style was a fresh take on the heist flick.

This is what Hollywood wants from you. They want you to take what they know, and twist it in a way only you can. On the flip side, if you try to write a 2017 version of Die Hard without some twist? Or a 2017 version of Jaws without a twist? If you try and write Face Off or Trading Places or Under Siege or City Slickers or Speed? Those types of movies are dead and gone UNLESS you’ve got a new spin on them (and NO, that doesn’t mean just turn the characters into women!).

And that’s the big problem with Airborne. It feels like a movie from another era.

Will Dixon (I mean come on – even the hero’s name is from a bygone era) is a commander on the USS Ronald Reagan, the stud of the U.S. military’s aircraft carrier fleet. After enjoying a quick break off shore from his duties, he’s told to suit up because something big and bad just happened in North Korea.

After they sail over to the NK, Dixon’s informed that a mysterious weapon has been tested and they need to gather intel on it. So they send a couple of SEAL teams in, who discover a thousand dead bodies who’ve been melted down into one long heap of flesh.

When they get back to the ship to report what’s up, it turns out one of the SEALS contracted whatever virus was used on the heap, and now the virus is spreading through the ship. Not only that, but the kill-rate is 100%. This is a SERIOUS bio-agent.

After the captain of the Reagan dies from the virus, the president reluctantly promotes the inexperienced Dixon to captain, where he will need to solve two problems. First, he must find a way to stop this fast-spreading virus from killing his entire crew. And second, he must decide whether to declare war on North Korea, who is preparing to attack the Reagan. I could go on, but I’m fairly sure you know what happens from here on out.

And isn’t that last sentence the most telling? That I’ve set up the first half of the movie for you, yet you don’t need me to detail a single page of the second half to know exactly what happens?

That’s one of the reasons Airborne feels like a script from a bygone era. It embraces that late 80s, early 90s, mentality of a simplistic plot setup with black and white heroes fighting black and white enemies. It’s action for action’s sake. There is NOTHING new.

And if there’s nothing new, you’re not doing your job as a writer. Because without “new,” there’s nothing to create a sense of wonder in the audience, a sense of, “I haven’t been here before therefore I don’t know what’s going to come next.”

I don’t want it to seem like this script was a total bust. I admired the attention to detail. All of the call signs and the language the crew members spoke seemed authentic, which helped sell the realism of the event. As I’ve said before: specificity breeds authenticity. And except for a few questionable calls (why are nurses who just worked on infected victims allowed to mingle in the mess hall??), there was a lot of detail and specificity to Airborne.

Another thing with these movies is the allure to resort to simplistic inner and outer character conflicts. It seems like in every one of these military scripts, the main character is battling some belief in themselves as well as battling a family member who’s also in the army. For example, Will Dixon’s father works back at the White House, and he doesn’t think Will has the chops to captain this ship. So Will’s trying to prove himself to his father the whole movie.

Look, I’m not against integrating cliche conflicts. The reality is, you only have so many options to work with. But we’re so influenced by screenwriting books and sites like this one, where I’ve written articles about how to institute flaws and conflict between family members, that we think it’s a requirement. But all it is is an option. You don’t HAVE to do it. And the truth is, most of the time, the writers who institute these flaws/conflicts, do so less to explore them, than to get that screenwriting coverage box checked.

And that never works.

The exploration of a character flaw or a family division or a character vice like alcoholism – those things only work if you’re genuinely interested in exploring them. For example, Will’s issues with his father back in Washington. Here in this script, it reads empty because it’s just checking a screenwriting box. But had the author anchored that relationship to his own troubled relationship with his father, and really dug deep into that, there’s a good chance we would’ve bought into it.

And that’s true with everything you write. If it’s not authentic, it probably won’t work. In the case of the movie Flight, with Denzel Washington, I wasn’t too keen when I read the first draft of the script. But when I saw the movie, the first thing I noticed was how much deeper they went into Denzel’s character’s alcoholism in the rewrites. The alcoholism wasn’t “checking a box.” They really explored what that disease does to a person. And I’d be surprised if screenwriter John Gatins didn’t anchor that alcoholism to something in his own life.

Anyway, let’s wrap up. One of your jobs a screenwriter is to find the fresh new thing, is to find stories that haven’t been told before or stories that have been told, but tell them from a fresh perspective. They don’t make movies like they did in your childhood anymore because those movies ran their course. If you want to steer those movies back into the mainstream conscious, you’ll have to do so with a new twist.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t box-check write. Box-check writing is when you’re more interested in getting the “I included what the screenwriting book told me to do” box checked than authentically exploring that element of your story. Screenwriters giving their characters vices like drug addiction or alcoholism are the worst examples of this. But it extends to everything, such as the father-son relationship here with Will Dixon and his dad. If you’re not willing to go all in on that and explore it from a truthful place, a better option might be to not include it at all.

Let’s talk about character descriptions for a minute, shall we?

You ever see that show “Botched,” about botched plastic surgeries? They need to make a show about botched character descriptions. Because I see them in nearly every script I read. For whatever reason, character descriptions trip a lot of screenwriters up. Luckily, you’ve got the guy who’s seen it all. Who’s read over 7000 screenplays. And he’s going to tell you what kind of descriptions work best. So, let’s jump into it.

There are four descriptions you’ll be working with.

1) Your hero.

2) Main characters.

3) Secondary characters.

4) Bit players.

Your hero gets the all-star treatment and can command anywhere from one to three sentences of description. This isn’t just to fully describe your hero. The long description is a visual indicator to your reader that this is the most important character in the script.

Sometimes, for story purposes, you’ll need to introduce other characters before your hero. This can lead to confusion, since typically, the reader assumes that the first character introduced is the hero. If you keep those pre-hero descriptions short then give us a big juicy description when your hero arrives, we’ll immediately know, “This is our star.”

Your main characters (the love interest, the villain) will get one to two full sentences of description. Secondary characters (the weird co-worker, the neighbor) will get one-sentence descriptions. And the bit players (a thug) will usually get a single adjective.

Descriptions are sort of like loglines. You’re trying to give us the highlights of that character without getting too specific. And here’s the important part. It’s more about the ESSENCE of the character, as opposed to the baseline visual facts of the character. I want you to read that sentence again because it’s where everybody screws up. Here, I’ll give you an example.

TOBY HANSON, late 30s, is tall with brown thinning hair, brown eyes, and glasses.

Everything I just told you there were facts. It doesn’t tell you anything about the character. Here’s the real description of Toby Hanson, the main character from the script, “Hell or High Water,” by Taylor Sheridan.

TOBY HANSON, late 30’s, a kind face marked by years of sun and disappointment, rides shotgun. It’s not the face of a thief, it is the face of a farmer.

Notice how we barely get any facts here. It’s more about the essence of the character, with the key phrase being, “a kind face marked by years of sun and disappointment.” Wow, that tells us so much! It tells us that this is a nice man who’s had a rough life, all in just 10 words! That’s how you pull off a description.

Moving on to main characters, here’s a description of Carolyn Burnham from Alan Ball’s Oscar-winning screenplay, American Beauty…

CAROLYN BURNHAM tends her rose bushes in front of the Burnham house. A very well-put together woman of forty, she wears color-coordinated gardening togs and has lots of useful and expensive tools.

That main character description is actually a little longer than the description for Sheridan’s hero. But that’s partly because Ball introduces Carolyn in action, tending her rose bushes. He needs to get through that first sentence before he can fully describe her. And, again, this description is bleeding with essence. She’s “a very well-put together woman.” She “wears color-coordinated gardening togs,” and has lots of “expensive tools.” Tell me you don’t know this character after reading that description.

Another description trick is to focus on how a character chooses to present himself/herself to tell us more about him/her.

For example, if I tell you that Jake has blond hair, you have no sense of who Jake is. But if I tell you Jake’s blond hair is always meticulously combed, never a hair out of place, you have a much better feel for Jake. He obviously cares about how he looks. If I tell you Carl wears jeans and a t-shirt, that tells you little. If I tell you Carl wears “skinny jeans and one of those overpriced vintage rock t-shirts that only celebrities can afford,” that tells you a lot more, doesn’t it? And all of this falls under the same umbrella. You’re trying to convey the ESSENCE of the character. Let’s see how we can use what we just learned to describe a secondary character.

LOGAN, 25, sports a boring navy blazer and boring khaki pants, the same outfit he wears every day of the week.

Finally, when you’re describing a character with a name but who’s only going to be in the script for a few scenes (a bit character), try to find that one adjective or phrase that captures them then move on. We don’t want to confuse the reader with some long description, making them think this is going to be some main character, then we don’t see them again for 60 pages.

PARKER, 40, always bitter about something, approaches the group.

In the end, screenwriting is still an art form and therefore the way you describe your characters is up to you. The above suggestions are merely guidelines based on reading a ton of scripts and seeing what works best. I’m actually pretty lenient when it comes to description length as long as the description is good. So you can play with the length if you want. But one thing I won’t budge on is the essence. A description is meant to convey the essence of a character. Always favor that over a perfect physical description, although preferably, you would do both.

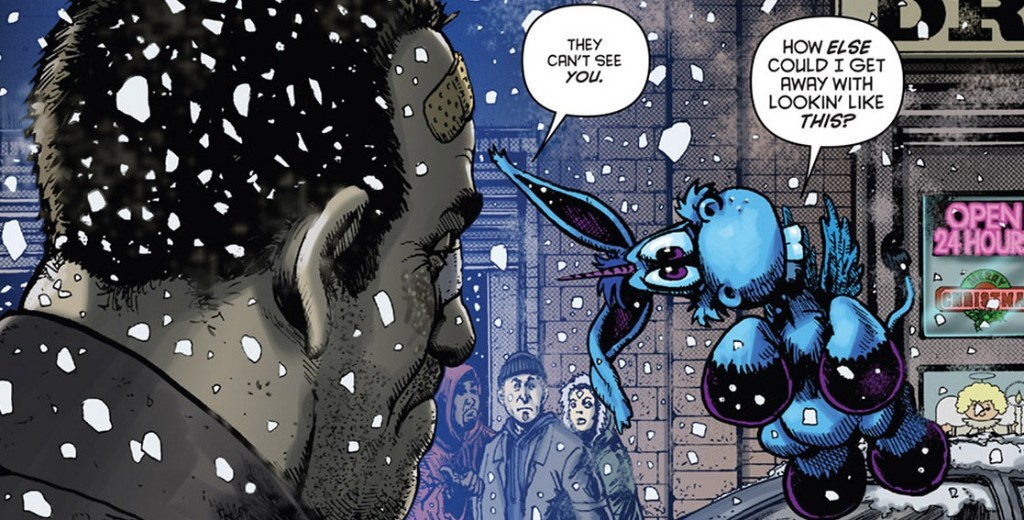

Just to show you that you still have plenty of creative leeway when describing characters, here’s a rule-breaking description of Nick Sax from Tuesday’s review of “Happy.”

NICK SAX is projectile vomiting into a urinal. Oh, what fun!

He steadies himself, wipes his mouth with a sleeve. Look at this guy: 40s. A 6’2” locomotive wreck in a worn out trenchcoat —

He steadies himself in the mirror… this is the face of a man who’s lost it all. Skin flaking with eczema; dead-eyed – but with something volcanic smoldering down deep behind them –

Genre: Action/Comedy/Crime

Premise: When a Brooklyn gun-for-hire is marked for death, he must find the man contracted to kill him first, the utterly elusive Black Phantom.

About: Jamie Foxx and Kevin Hart have wanted to work together forever and this was supposed to be the project that finally did it. The script, which was originally written in 2009, was supposed to be a vehicle for Samuel L. Jackson. Rumors that he shot the film between Avengers’ takes have since been debunked. The project was smartly pitched as a no hold’s barred non-p.c. smashmouth comedy team-up flick. But just like so many projects in town, it got lost in a sea of actor scheduling hell. Something tells me this movie will end up getting made though. It sounds too fun not to.

Writers: Dave Lease & Megan Hinds

Details: 116 pages – April 20, 2009 draft

One of the things I talked about in my newsletter was that, when you’re trying to sell specs to Hollywood, you want to write in one of two lanes. The first lane is whatever’s trending. Female-led action thrillers and compelling true stories are two of the most prominent at the moment. The other lane is movies that Hollywood has been buying and making forever.

The comedic two-hander lands squarely in that second lane.

We just saw it these past two weeks with The Hitman’s Bodyguard finishing at the top of the box office. The brilliance of this sub-genre is that the execution doesn’t have to be perfect. It’s more about writing two fun characters who are the last people who’d want to be stuck together.

Now, when you write a comedic two-hander, you have three options. You can team your characters up on the right side of the law (two cops – Rush Hour), you can team your characters up on the wrong side of the law (two criminals – 2 Guns). Or you can team your characters up from both sides of the law (Midnight Run). I suppose there are additional options I’m not thinking of but those are your main three.

Of these three, I think option 1 is the least interesting. It’s just that we’ve seen SO MANY wanna-be Lethal Weapons over the years. Unless you’ve found a fresh way into the cop team-up genre (Netflix’s “Bright”), I’d avoid it. There’s still plenty of originality to be found in the other two categories, though. So it’s smart that Black Phantom went the two criminals route.

And I love the way it’s pitched. As this “No boundaries” let’s throw politically correct out the window setup. We need movies that make fun of our new ultra-sensitive generation. So let’s see if The Black Phantom delivers on that promise!

Benny Bonnema is a pint-sized contract killer who doesn’t like the fact that his partner, a big brute known as “The Russian,” gets all the recognition. Benny considers himself to be the brains of the operation. So why does this big lug have a price-tag on his head five times higher than Benny’s??

Anyway, there are two main crime leaders jockeying for position in the Bronx. There’s the Armenian, Kadakian. And there’s the Italian, Pascalli. Benny and The Russian are hired by Kadakian to kill a group of upstarts who just stole a cocaine shipment from him.

This is a cakewalk for someone like Benny. And he does the job barely breaking a sweat. But then a mysterious man comes out of nowhere and kills The Russian! Benny runs from this psycho, barely getting away. Later, when he queries his contact list, he finds out that the man who tried to kill him, and who will continue to try and kill him, is known as…. The Black Phantom.

Nobody knows who this guy is or where he came from. But Benny realizes that if he’s going to stay alive, he needs to find answers to those questions. Give Benny credit. He’s a smart dude. He’s able to track down The Black Phantom and, after a chat, learn he was hired by Pascalli to kill him.

Since Benny got the drop on Phantom, he gives him a new option. Help him kill the Pascalli crew. Truth be told, Phantom doesn’t have a choice. Benny’s putting Phantom’s wife and kid in a 36 hour chamber that will stop pumping oxygen in if Phantom decides to kill Benny. And so the two team up to take down the Italian mob!

Man. For a script built on ‘anything goes,’ not enough went.

This is actually a great script for beginners to read in terms of learning how a series of small technical mistakes can kill a script.

Let’s start with The Black Phantom himself. This is the title of the script. This dude is elusive. This dude is a badass. This guy is supposed to be the creme de la creme of contract killers.

Except our hero easily finds him then quickly turns him into a little bitch. Because Benny’s got his family locked up, Black Phantom has to nod his head and do whatever Benny says. You’ve just mitigated your entire concept. The cool mysterious badass main character cannot be cool, mysterious, or badass. That right there was a Game Over mistake.

And there were more where that came from.

When you’re writing a fun light-hearted comedy team-up film, you don’t have one of the guys on the team lock the other’s wife and young kid up in a 36 hour oxygen chamber while they’re on their mission. That kind of takes the wind out of any potential witty banter, don’t you think?

I understand what happened here. You had to find a motivation for Black Phantom to work with Benny. So you locked up his wife and kid. But people, you can’t just throw anything in there to get a plot hole filled up. It has to make sense within the context of the story AND it has to fit inside the genre itself. This is a comedy. Not a Hannibal Lecter prequel.

Also, choices like that make your hero hateable. We’re not going to root for or laugh with a guy who’s suffocating little children.

It was little mistakes too. For example, when Benny tells Black Phantom he wants to kill the Pascalli gang, Black Phantom responds with – “Oh yeah, let’s just go kill the entire Italian mafia.” Benny comes back with: “Italian mafia? Oh man! You watched too much television in Charlotte, Phantom. The Lucky Luciano, Carlo Gambino, John Gotti days are over, man. Pascalli’s got like eight fucking guys. He’s a glorified crew at best.”

Nooooooo!

When you set up a task for your heroes, you want it to be impossible! You want it to sound like the most impossible task ever. That’s why we watch! Cause we’re wondering, “How are they going to kill the entire Italian mafia??” With this one statement (“They’re just a tiny outfit”), you instantly destroy half the movie’s drama. Jesus. You don’t want to make things EASIER for your heroes. Make them harder! Again, major beginner mistake here.

Look, I like this setup. I can see this trailer. But going off of the script, I can see why this project hasn’t picked up steam. Actors have to read a script and be excited. This doesn’t even obtain a fraction of the fun this premise promised.

For starters, you need to make sure that the Black Phantom is badass all the way through. You can’t have his balls ripped out 45 minutes into the movie. That fix alone makes this script a thousand times better. From there, don’t make weird choices like oxygen chambers keeping family members alive. Just give The Black Phantom an equally big reason to want to kill the Pascallis.

Sheesh.

This project has potential but we need some veteran comedy writers on it that know what they’re doing.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t fill your plot holes with cheap concrete. They’ll just go right back to being plot holes. Every plot hole should be filled with a solution THAT MAKES SENSE and THAT FITS INTO THE GENRE you’re writing in.

Easily the best TV or MOVIE concept I’ve seen all year. But might it be the best concept I’ve seen all decade??

Genre: TV Pilot – 1 Hour Drama

Premise: After a hitman is injured during a job, he wakes up to find a tiny blue horse named “Happy” floating over him, claiming that they’re now a team.

About: Pitched by some as “The Bad Lieutenant meets The Care Bears,” Happy was a four-episode comic by Grant Morrison and Darick Robertson that’s now been adapted for the SyFy Channel. Morrison has brought in Brian Taylor, who’s best known for writing the Jason Statham actioner, Crank, to help him realize his vision.

Writers: Grant Morrison & Brian Taylor (based on the comic with art by Darick Robertson)

Details: 61 pages (Network 2nd Revision – July 27, 2016)

After the depressingly formulaic Rampage, I needed something that was out there, man. I haven’t seen many writers taking chances on the feature end. But there’s plenty of chance-taking on the TV side.

Due to the enormous level of output in TV at the moment, there are two ways to stand out. The first is to buy up a well-known property. Basically, the movie model. And the other is to write something really unique. Today’s script falls into the latter category.

And, actually, today’s script probably has the best screenwriting lesson I’ve discovered in awhile. Because this hook is insanely clever. You see, I read a ton – a TON – of imaginary friend based concepts. It’s the idea every writer goes to when they think they’re writing something original. But today’s script is the right way to do imaginary friends, and the secret to finding a truly original idea.

I’m sure you’re eager to hear more, so let’s jump into it.

“Happy” begins with a creepy teaser. A mother is taking her little girl, Hailey, to see one of those Teletubby-type performances at the local mall. However, with Christmas right around the corner, every family within a 20 mile radius is there as well. That’s how the ultimate parent nightmare occurs. The mother gets distracted for one second… and Hailey is gone.

Cut to a different part of town. Nick Sax is a hitman, and a very un-HAPPY one. We’re told from the drop that this is a man who’s lost everything and has no reason to keep going. But he does. Nick’s just been offered a job to kill the Fratelli brothers, three annoying low-level mobsters.

Sax completes the job, but gets injured in the process. Before he passes out from the injury, a dying Fratelli brother shares with him a password for a drive that contains every single mobster in this city’s secrets.

Sax wakes up in the hospital, but with a new friend. A tiny little blue pony/horse with a unicorn. This is Happy. And Happy is so… HAPPY! He’s excited that Nick’s finally awake. He starts singing to him. He can’t wait for the two to go on adventures together. Nick assumes this is some drug-induced hallucination and waits for it to go away.

Meanwhile, the guy who ordered Sax to kill the Fratellis has ordered someone else to come and kill Sax. But not before he gets that password. Sax is helped by a local female cop, or at least he thinks he is. Not everybody is who they seem, here. And the cop may be working for the guy who’s trying to kill him. Or maybe not!

When the drugs finally wear off, Sax is dismayed to see that Happy the Horse is still around. Sax starts arguing with him, telling him he isn’t into the whole imaginary friend team-up thing. “I never had any imaginary friends anyway,” he tells Happy. Happy chuckles. And that’s when he reveals a bombshell. “I’m not your imaginary friend, Nick. I’m Hailey’s. And I came to you because you’re the only one who can help save her.”

Okay, so let’s break down the genius of this concept. Because if you’re cynical like me, you originally saw the Happy Horse thing and thought, “Zoinks! An imaginary blue horse teams up with a hitman because… COMIC BOOK!”

When that bombshell was revealed that Happy wasn’t Sax’s imaginary friend, but the little girl’s who had been kidnapped in the opening, I was like BSSHSHSHEGGSH! Mind blown. Not just because it was a great idea. But because there was a story-related motivation for Happy to exist.

But let’s get back to the lesson of the day here, specifically the point I originally brought up.

Everybody thinks they’re being creative when they come up with the imaginary friend concept. The problem is, they’re not creative at all. I see tons of them. And they almost always take the same form. An adult is visited by their old imaginary friend from when they were a kid.

Whenever you have an often-used idea, your job is to twist it or elevate it somehow, so that it’s different from everything else out there. The problem is, everybody goes about twisting it the wrong way. They think two-dimensionally when they should be thinking THREE-DIMENSIONALLY.

Two-dimensional thinking is the obvious “next step.” So if you have your “Grown up imaginary friend” setup, a two-dimensional thought might be to make the imaginary friend EVEN CRAZIER! So if the childhood imaginary friend was a bunny, you’d make the bunny a sex-crazed gun-toting wild card! Sounds good, right? But you haven’t really elevated the concept. You’ve just made the imaginary friend a little more interesting.

Three-dimensional thought is when you think beyond what’s right in front of you. You approach the idea from several angles. This is not easy, guys. It’s the quantum computing of idea generation. But that’s why when it works, it results in a killer concept. And that’s what they did here.

This concept is NOTHING if Happy was Nick Sax’s imaginary friend as a child. It’s literally NOTHING. It’s a gimmick. It’s tired. It’s an excuse to get some cool comic book art in. By thinking outside the constraints of that tired setup – what if you were visited by SOMEONE ELSE’S imaginary friend – the idea comes alive. And that’s what happened. And it wasn’t just that it was someone else’s imaginary friend. It’s a little girl’s imaginary friend who’s missing and who needs Sax’s help. Which is why Happy came to him!

I can’t get enough of this idea. I just can’t. This is everything you’re supposed to do with a concept. It’s so damn clever.

And the funny thing about all this is that we don’t get Happy’s reveal until 45 pages in. And before that, I was like, “Eh, this pilot isn’t bad, I guess.” I wasn’t really into it. This is classic noir that, outside of the imaginary friend angle, embraces all the noir tropes a little too eagerly. Which sucks because on concept alone, I’d give this a genius.

So those of you seeing me rave the whole review then only giving this a [xx] worth the read, that’s why. I think this project needs people better than Syfy, no offense. But Syfy has embraced cheese as their curator and this has the potential to be one of the buzziest shows on television with the right people behind it. So I’ll hope that Syfy passes and a Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, or maybe even HBO picks it up. That would be fucking awesome.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Three-dimensional thinking is hard to define. But the basics work like this. When trying to improve an idea, don’t think “bigger, better, flashier.” Instead, take an omniscient view and look at the idea from all sides to see if there’s a hidden angle you can exploit. They do this in the tech world all the time. Uber is an example. People come in and they say, “How do we make a taxi service that’s better than all the other taxi services out there?” Two-dimensional thinking is: Well, we add TV in the back and we make the cars cleaner and we only hire drivers that are nice and courteous. All that stuff is fine but it doesn’t change the game. Three-dimensional thinking is: Eliminate the taxi altogether.

If all is right with the world, you should be receiving a Scriptshadow Newsletter with a brand-spanking new top secret sci-fi project script review by tomorrow morning. If you want to sign up for the Scriptshadow Newsletter, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “Newsletter” and I’ll add you on.

Genre: Sci-Fi Adventure

Premise: Based on the sorta-famous 1980s video game, Rampage, three animals are infected with a virus that makes them grow exponentially larger and stronger.

About: Rampage is one of the more improbable projects out there. Based on an arcade game that only true arcade geeks remember, the project somehow got the biggest movie star in the world, The Rock, to sign onto it. I’m guessing by offering him an unheard of amount of money. The original script assignment went to Ryan Engle, who wrote Non-Stop (Liam Neeson). Current revisions were done by Adam Sztykiel, who penned the Robert Downey Jr. and Zach Galifianakis road trip comedy, Due Date, as well as 2015’s Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Road Chip. The film is directed by Brad Peyton (San Andreas), and will be a big 2018 summer release.

Writers: Ryan Engle and Adam Sztykiel

Details: 116 pages

Here’s a little industry trick.

If you want to make a giant movie that’s similar to a major property, simply find an obscure property in the IP universe that’s in a similar vein, option it, and make that movie instead.

How do you make Godzilla or King Kong if you don’t have the rights to Godzilla or King Kong? You option little known 80s arcade game, Rampage! That’s how.

I’ll be honest. I was a BIG Rampage fan back in the day. Giant animals climbing buildings and destroying shit? How could you NOT be into that.

But how do you make a movie based on that? How do you create a mythology to make the animals big in the first place? And once you have them, how do you get them into the city? And once they’re in the city, how do you get all three of them climbing buildings? Why would giant animals all of a sudden be like, “Yo dude, let’s climb these buildings!” And how do you make it all believable? At least in relative movie terms? That was the challenge today’s writers had. Let’s see how they did.

Davis Ridley works at the San Diego Zoo as a gorilla wrangler, and there’s nothing he loves more. That’s because Davis gets along with animals better than he does humans. “You always know where you stand with animals,” is Davis’s mantra.

Meanwhile, up on the space station, because of course there would be a space station, a top secret project has gone haywire, killing all the scientists inside and sending the station spiraling into earth’s atmosphere. The station breaks into three pieces, crashing in three separate areas of the U.S.

One of those pieces lands near the San Diego zoo, where Davis’s favorite gorilla, a silverback named George, gets a hold of it. A few hours later, he’s leapt over the 20 foot high enclosure, found a bear, and mauled it to death. Davis is worried.

Soon after, Dr. Kate Caldwell shows up. Kate used to work for the space station company before getting fired last year. Kate is one of the few people who knows what’s going on. Any animal that gets a whiff of her secret virus will start growing infinitely bigger and stronger. And if you guessed that Kate and Davis don’t get along yet their interactions include a steamy romantic subtext, you’d be right.

Meanwhile, back at the Sears Tower in Chicago, the brother-sister CEOs of the space station enact a protocol-beacon of sorts that trigger the infected animals to come to them. I’m not sure what their ultimate plan is once these monsters show up in the middle of one of the biggest cities in America, but who cares! It means giant animals climbing buildings, baby!

Along with George the Silverback Gorilla, there’s a giant-ass wolf and a giant-ass crocodile also coming to join the fun. Will they make it to Chi-Town? And if so, how much building-climbing will they get in before the visual fx budget runs out? And how does The Rock fit into all this? You’ll have to wait until 2018 to find out, cause no way am I spoiling the rampage!

It was really interesting reading Rampage after the sci-fi script I review in the newsletter. One is the very definition of “taking chances,” while the other, Rampage, is the essence of formulaic. And I’m not saying that’s a terrible thing. 200 million dollar movies are going to be more formulaic than not. But therein lies the challenge. You have to take chances and be original SOMEWHERE. Or else there’s nothing to distinguish your movie, nothing to make it stand out or memorable.

Rampage was painfully predictable. It’s got the overcooked character flaw for its protagonist (he likes animals more than humans). It’s got the forced sexual conflict with its leads, Davis and Dr. Kate. All the plot beats, such as the inciting incident and act turns and relevant twists come exactly where they’re supposed to.

I struggled to find even ONE thing about this script that was a unique choice. I eventually came up with the CEOs of the space station company. The writers could’ve gone with the cliche mustache-twirling villain, but made it a brother-sister team instead. So at least there’s something original in the script.

Look, I’m not going to pretend that writing these scripts is easy. When you’re sending drafts into producers, they’re not coming back at you with, “Less Jurassic Park and more David Lowrey’s ‘A Ghost Story.’”

So the question becomes, how DO you make these scripts original?

I think it’s those little choices, like the brother-sister CEO team. If you can make a bunch of little original choices like that, they accumulate and the film starts to feel like something of its own.

But you also have to get the characters right. A huge problem writers run into with these movies is they just accept generic archetypes. When they’re writing Davis’s scenes, they’re not thinking, ‘What has this person been through in their life?’ They’re thinking, “What cool one-liner could The Rock say here?” And I admit, that’s fun to do. But I’d argue that understanding a character’s backstory and biography in a 200 million dollar movie is more important than in some Oscar-bound indie flick.

In the indie flick, the gritty dark palette of the screenplay leads us to give the characters the benefit of the doubt. In contrast, you have to actually work to convince us that the main character in a giant sci-fi adventure film is a real person. And if you don’t do that work? The character feels fake. And by association, everything he engages in feels fake.

Davis’s “Me like animal more than human” m.o. is a dime-store flaw. It’s the very definition of movie logic and doesn’t take into account how a real human being could’ve gotten to this place in their life, or if he should even be there at all.

I don’t know. Maybe I’m digging too deep. Maybe they’re just trying to make the Godzilla/King-Kong version of Tremors. A goofy fun silly adventure where nobody takes what’s happening too seriously. I just think it’s dangerous to do that. Whenever you move away from truth and real life, you get empty movies. Which is why I probably won’t see Rampage unless it has the best trailer ever.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The forced “we don’t like each other because this is a movie” relationship between Davis and Dr. Kate really annoyed me. Remember guys, CONFLICT is not a reason for a character’s action. People don’t engage in conflict because they want to engage in conflict. In real life, there’s always a REASON behind the way people act towards one another. In Seinfeld, there was this super annoying character named “Bana,” a terrible comic who Jerry despised and never wanted to talk to. The Seinfeld casting directors scoured the acting ranks to find Bana. The direction they kept giving during auditions was, “He’s really annoying.” So hundreds of actors came in and they tried to be REALLY ANNOYING. The problem was, that’s all they were trying to be. Annoying. There was no reason behind their annoyingness. It was just to meet the character requirements. When the actor who eventually got the Bana part came in, he recognized that this lack of reason behind the annoyingness was a problem. So he asked, “WHY is he annoying?” And he came up with this little adjustment where Bana just really wanted to be Jerry’s friend. THAT’S why he was annoying. The casting directors were instantly on the floor laughing at the interpretation and the actor became one of Jerry’s favorites. Jerry would continue to find as many ways as possible to fit Bana into episodes. The point is, characters don’t just do things cause: SCRIPT. You have to find reasons behind why characters are acting the way they do. Then, and only then, will they come alive.