First off, an update on the Super Breakdown. A lot of submissions. I haven’t decided when I’m going to do it yet. Probably in the new year in the 2nd or 3rd week of January. But just know that I’m looking through all of the entries to try and find one. I don’t really know what the criteria will be. I’m not actually looking for a great script. I’m looking for something that sounds interesting and that I feel has the potential to learn from.

Moving on… Lol. Guys. To be clear. I’m JOKING about the micro-script craze. I don’t consider it to be a thing. A story should be as long as it needs to be. If you have 1 character in a coffin for the entire movie, that script’s probably going to be short. If you have a sweeping epic that covers three families over 100 years, that script’s probably going to be long. But don’t think everything has to be 80 pages.

Okay, on to this weekend’s offerings! Here’s how to play: Read as much of each script as you can and submit your winning vote in the comments section. Votes will be counted through Sunday, 11:59pm Pacific Time. Winner gets a script review next Friday!

For those who want to play in future Amateur Offerings, send me a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and why you think people should read it (your chance to really pitch your story). All submissions should be sent to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com.

Script: Plummet

Genre: Horror/Thriller/True Story

Logline: Lured by a sadistic killer, a young woman fights for survival in Central Park during the dead of winter. Based on true events.

Why You Should Read: Because this is a contained thriller that really happened about a real serial killer you’ve never heard of. It also takes place in one of the most original “contained” places imaginable. To say more would spoil the reveal. Thanks for considering.

Title: MONSTER ASSASSIN

Genre: Supernatural Action

Logline: When the love of his life is murdered by a group of demons, a legendary monster assassin sets out to exact revenge.

Why You Should Read: Because it’s a 90 pages micro script in the vein of “John Wick” with a supernatural twist. I poured into it my passion for the Gothic and macabre, my love of wildly imaginative action and my heart’s yearning for a magical world hidden within our own. Plus, you can play a game of spotting all the references to Edgar Allan Poe’s tales and poems…:)

Title: Righteous Anger

Genre: Thriller/Drama

Logline: A 17-year-old Syrian refugee becomes entwined in a dangerous world of deceit and human trafficking in his Atlanta community.

Why You Should Read: Atlanta is a hot market for filmmaking right now. It’s also home to one of the most diverse refugee communities in the nation — oh, and home to some of the worst human trafficking incidents in the country. All these ingredients combine to make a tense, difficult experience for our hero, Sammi, a newly arrived Syrian refugee. — As a team we spent weeks ensuring this story had movement, depth, and a topic that would hook today’s audience. You go in thinking your going to get a political diatribe, but you leave getting a tightly wound story following a young man’s experience with the criminal underbelly of a large US city. It goes from PBS to “Prisoners” real quick.

Title: Two-Time

Genre: Crime Drama

Logline: After allegations of game fixing derail his career, an ex-college football star is recruited by a disgraced university booster to steal the three National Championship trophies they helped win.

Why You Should Read: If the last decade’s taught us anything, it’s that crime and football go together like spaghetti and meatballs. It’s in this relationship that “TWO-TIME” lives, not as a cliche feel good sports story but a gritty breakdown of life after the money and pussy. This script plows head-on into a world lost in the arena-focused sports film, packaging a timely thematic take down of amateur athletics in a digestible crime narrative… “BLUE CHIPS” meets “HELL OR HIGH WATER.” — I hope that, beneath all of the cynicism in this script, you find a deep love of college football and all that encompasses it… Good and bad. — Thank you for giving “TWO-TIME” even a moment of consideration and I appreciate any and all feedback.

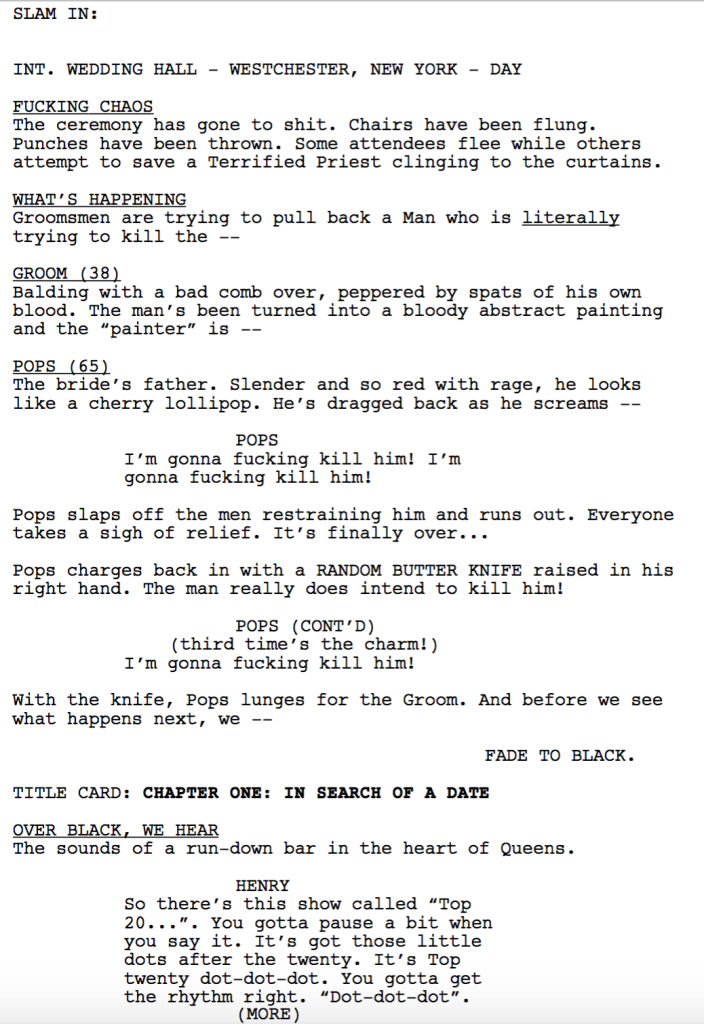

Title: …’Scape The Lightning Bolt!

Genre: Dark Comedy

Logline: Henry has the purest intentions. All he wants is to see his sister happy, but when he accidentally sets her up with a violent psychopath with a peculiar motto (‘Scape the Lightning Bolt)… his life takes an unexpected turn for the worse.

Why You Should Read: So a few years back you held a dialogue contest. A scene of mine was by far the unanimous favorite. You compared it with a famous scene from one of your favorite movies (Silver Linings Playbook) and said that my scene held up well. It was a big morale booster for me and I’ve never forgot it. So here’s the thing: I was young and, instead of making my script the best it could be, I gave into the pressures of people saying I needed to convert my story into a visual, action extravaganza (something that it was inherently not). You can’t make a cow bark and soon I grew frustrated with endless rewrites leading to nowhere. I ended up focusing on other literary mediums. But never could I purge this story from my mind. So that’s why I’m here now with a shiny new draft that finally leans into my strengths. I guess what I’m saying is that instead of trying to bark, I’m mooing really loud and you should check it out, cause it’s really fucking good.

Genre: Action/Thriller

Premise: As an ex-soldier interviews for a cushy corporate gig, the unstable Security Chief she’s there to replace seizes control of the high-tech industrial complex.

Why You Should Read: Hollywood’s overstuffed with Jane Wick specs, it’s time for Jane McClane to get her shot. In his recent article, “How to Jump Start the Spec Market”, Carson claims that a fresh spin on real world action can fire up the film industry. I believe a contained modestly budgeted female driven take on the original Die Hard hits that bullseye. Part of that fresh spin includes modernizing the setting. I chose the baffling Agile Scrum anti-privacy open space office design that’s been made popular by Apple and Google. I hope it achieves the same effect of an old school cop feeling out of sorts inside a high-tech skyscraper.

Writer: Brett Martin

Details: 90 pages

Excited to read Brett Martin’s latest. He always has a great attitude and is very professional. For those who read his script two weeks ago, note that this is a new draft he sent me where he incorporated your notes. So if I bring something up that you don’t remember, that’s probably why.

Also, before I get into the review, I encourage all of you to watch The Disaster Artist this weekend. I’ll be reviewing it on Monday. I CAN’T WAIT to see it!

20-something Naomi has just learned that she’s pregnant. Which sucks. Because she doesn’t want to have kids. That’s despite loving her boyfriend, Marcus, with all her heart. This is also the worst time to learn she’s pregnant, since she has a big job interview at a company called Poly Vac, which has figured out a way to airdrop portable surgery packs that allow doctors in isolated areas to perform complex surgeries.

But Naomi senses something is off the second she gets there. There are a bunch of soldiers in the waiting room, presumably up for the same job, and no one will tell her anything about the fired guy whose job she’d be replacing.

A former computer tech in the army, Noami stays professional, going to each and every station in the company to get interviewed by the company heads. But as she’s finishing up, the entire building is locked down, and everyone is locked in.

This is when we meet Griffin (well, sort of – more on that later), the disgruntled former employee no one would speak of. Griffin wants a pound of the CEO’s flesh, several million pounds of his money, and he’s not afraid to kill anyone to get it.

Oh, and those soldiers who were “up for the job?” Yeah, they’re on Griffin’s pay roll. Griffin then steals the CEO’s laptop and does one of those “money transfer from offshore accounts” downloads, which unfortunately takes awhile. This leaves time for people to act up.

When people start dying, Naomi has no choice but to get involved and fight back. She’s able to steal the laptop and isolate herself in another part of the building, temporarily preventing the money transfer. So Griffin sends his goons after her with next to zero success. It’s looking like Naomi will come away the victor until her boyfriend shows up to pick her up from the “interview.” Once Griffin gets his hands on him, the leverage pendulum swings back in his favor. And that means Naomi, as well as everyone else in the company she’s been protecting, is dead meat.

Let’s start with the good.

This is a very competent screenplay. It’s professionally written. It’s tight. It moves quickly. There’s a “writer who knows what he’s doing” sheen on the script. This isn’t someone who picked up screenwriting last week.

However, there were issues, some small and some big. On the small side, the script starts oddly. We have this weird opening scene where our villain, Griffin, basically tells another character what he’s going to do. It was difficult to understand the reason for this. It would be like in Die Hard if Hans Gruber showed up a week early, strolled up to the front desk, and said, “Watch out. Next week? I’m going to hold this building hostage. Here’s my resume, by the way. In case you want to know more about me.”

This was followed by Naomi’s job interview, which I spent half the time re-reading because I didn’t understand what was happening. Why are a dozen soldiers hanging out in the CEO’s office? Oh, wait. They’re job applicants? But… why are they dressed in their soldier uniforms? If that’s a requirement, shouldn’t Naomi be dressed in her military uniform as well? But again. This isn’t a military company. It’s about doctors and airdrops right? So what’s with the whole military job applicant theme? It was confusing to say the least. I got over it. I just hate when things are unnecessarily confusing, espcially early on in a script.

After that, the script gained clarity. But then it ran into its big problem. And I want to frame this in a way where it helps Brett. Because I know Brett wants to get good at this. But here’s the issue: There aren’t any original ideas in this script. It was almost shocking how by-the-numbers everything was. And I say that because Brett reads this site all the time and one of the dead horses I’m constantly beating is to ask yourself, “What’s new that I’m bringing to this concept?” “What’s new that I’m bringing to these characters?” “What’s new that I’m bringing to this scene?” To this set-piece, to this plot choice, to this dialogue, to this genre? And I can’t imagine any scenario where you’d evaluate this idea and say, “I’m bringing something new to this.”

If this were a court case, I suppose you could argue that some of the plastic-making rooms were original. And they were. But a couple of fun action scenes in unique rooms isn’t enough to save a script where everything else was so predictable. It was so straight-forward I actually thought I was being set up for a monster twist that was going to turn everything on its head. But it never came.

Contained location

Ex-military protagonist

Learns she’s pregnant

Angry ex-employee

Motivation is lots of money

Offshore accounts

The infamous “downloading” bar

Mindless minions with guns going after our hero

You gotta take chances. You gotta try new things. You can’t be too formulaic. One of the things I say here is that you find greatness through how you break the rules. This script never once stepped outside the lines and if you don’t do that, the reader gets ahead of you. They’re waiting for you to catch up to them. Cause they already know what you’re going to do 30 pages down the road. Your lack of surprises has guaranteed that no surprises are coming later either. The reader knew, for example, the boyfriend was going to come back and get mixed up in this.

One of your big jobs as a writer is to place yourself in the mind of the reader and ask, at every step, “What does the reader think I’m going to do right now.” And every once in awhile, you HAVE to give them something different from what they expected. And that never happened here. Which is surprising since Brett has been reading the site for so long.

So I’d like to ask Brett that question for the comments. Is that something you didn’t consider? Or did you think you had made original choices? And if you did, what were those choices? I know you said the rooms were different. But did you think that was the only difference you needed?

Maybe the community and myself can help you recalibrate what constitutes a unique choice. Because there isn’t enough imagination here. And that’s it really. I could go into more detail but everything from the concept to the execution was too formulaic. If that issue isn’t fixed in this or future scripts, you’re going to get a lot of the dreaded “polite no’s.”

I can’t stress this enough for ALL aspiring screenwriters. You need to write something THAT GETS PEOPLE EXCITED. The kind of thing that makes them want to leap out of their seat and go tell someone, anyone, what they just read. A by-the-numbers contained action thriller isn’t going to do that. You need a new angle, as well as a more adventurous approach to the plot.

Screenplay Link: Wrongful Termination

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you want to get noticed in Hollywood as an amateur screenwriter, probably one of the top 5 ways, if not top 3, is to consistently make original choices. It doesn’t seem that way because of the formulaic movies Hollywood puts out. But that’s not how new writers are judged. They’re not judged by their ability to also make formulaic choices. Producers are looking for writers who bring something new to the table as they represent the only opportunity to write stuff that stands out from the pack.

Yesterday’s script review reminded me how rare it is that a script actually recovers from a bad second act. I know this because when I first started giving notes, I came up with an idea I thought would revolutionize the notes process. It was my belief that the reason so few writers improved their screenwriting skills was because they didn’t know what the reader was thinking when they were reading their script. Most feedback a writer receives is general. “I didn’t like the main character.” “I got bored in the middle.” “I was hoping to laugh more.” “The dialogue was only okay.” That doesn’t help a writer improve.

What if you could be INSIDE THE READER’S HEAD as he was reading your screenplay? You would know exactly what was wrong, when it went wrong, why the reader checked out, the action that made them dislike your hero. It was the ideal teaching tool! So I came up with this idea of creating “Real Time Notes.” The idea behind them was this. I would create a graph charting all 110 pages of the script, and at the end of each 10 pages of the graph, I would give that section a 1-10 rating (1 being the worst, 10 being the best), as well as explain the rating.

So a typical section might look like this: 7 out of 10. “Good introduction of your main character. He seems like an adequate badass. A more original entry scene into the story would’ve scored higher points. I’m digging the mystery behind this secret facility he’s been recruited to visit….” and so on and so forth.

I was convinced I’d revolutionized the process of screenplay analysis.

Then I began implementing it. And what I found was that the script sections didn’t vary as much as I thought they would. The first ten pages wouldn’t get a “3,” then the next ten a “9,” then the next ten a “5.” It turned out that nearly every script (90%) followed the same formula. They would start out decent-to-good. The first ten pages might get a 6 or a 7. This was due to the newness of the story and a general excitement of being dropped into a new universe. Similar to what Jerry Seinfeld says about stand-up. “The first 5 minutes they’ll laugh at anything. Then you have to be funny.”

The second ten pages would get a bump, as this was where the INCITING INCIDENT took place – the main character’s “problem” being introduced. Buzz Lightyear arriving as a present in Toy Story, for example. The inciting incident is often the “plot-starter,” and therefore a naturally exciting moment in the story.

It was inside the third ten pages that the cracks would begin to show. And they’d show quickly, splintering out with increasing intensity after every page. Without the newness camouflaging flaws and without the excitement of the inciting incident, the writer would actually have to start writing. And if they didn’t know how, they couldn’t hide from it. Have you given us a main character we like? Have you introduced an intriguing mystery? Do all your scenes have a point? Are we clearly moving towards a goal or trying to answer a question? Are the stakes high? And are you coming at all of this in a way that’s fresh and unexpected? Typically, these third ten pages result in a 2 to 3 point dip.

Then we get to the fourth ten pages. Now we’re officially in the second act. And for someone who didn’t know what to do in those previous ten pages, holy shit do they not know what to do in this fourth set. You can feel them grasping at straws, trying to think of what to do next, rather than introducing another piece of the puzzle with confidence and conviction. The fifth, sixth, and seventh sets continue to get lower scores. The “mildly decent” scripts manage to stay at a 3 or a 4 rating. But most will dip to a 2.

Almost all scripts gain back a couple points in the last couple of sections, as the third act forces the writer to focus. Having to wrap things up ironically gives them no choice but to add goals and clarity, things that were lacking in the second act. This bumps up the interest a tad. But not much. It’s too hard when you’ve bored a reader for that long to make them excited again.

So almost all of the scripts looked like this, with only minor variances…

6…7…4…3…3…2…2…2…2…3…4

And, honestly? That “4” at the end? Was partially because I was so happy the script was over.

I continued with my real-time analysis for a few months, but ultimately decided it wasn’t helpful. It’s depressing looking at your script get a bunch of “2’s.” And writers are depressed enough already. I wanted my notes to focus more on helping the script get better, not pointing out how bad it was.

But it was a huge learning experience for me. Because it gave me a mathematical representation of what the reading experience is for the majority of screenplays out there. Almost all of them follow the same pattern. And from it I learned two huge lessons.

The first is that if you don’t properly set up the foundation of your story in that first act, your second and third acts don’t stand a chance. And by “properly set up” I don’t mean getting polite 6s and 7s because you’ve managed not to screw up the easiest section of the story. You need 8s and 9s. Grab us by the balls and set up a cool ass journey that we want to be taken on.

The most common example of failing that first act test is introducing a boring main character. When you do that, it doesn’t matter what’s going on with your plot in the second act. We’ve already decided we’re not interested in this person’s journey. Or, if you’ve given us a strong protagonist, not introducing interesting enough problems for that protagonist to overcome, or interesting enough mysteries or goals for them to pursue. If you didn’t set up some compelling plot problem in that first act, it’s only a matter of time before we get bored.

The second is that very few writers understand how to construct a second act. They think it’s a matter of organically figuring things out along the way, not understanding that when you do that the reader feels it. They sense your lack of conviction, something that becomes exponentially apparent the further into the act you go, as your plot choices more readily exemplify a writer running out of ideas. When people tell you to outline a script, what they’re really telling you is to outline your second act. Everybody knows how to start. Everybody knows how to finish. What happens along the way is where writers get lost.

The reason, then, those second act sections get such low scores (3s and 2s) is because they’re compounding two problems. One, that they didn’t properly set up a great hero and exciting story in the first act, ensuring the middle 60 pages will be boring. But on TOP of that, they don’t know how to write a second act anyway! Even if they’re one of the few who build a strong foundation, they don’t know the secrets to crafting a good second act (a strong goal driving the hero, constant conflict, unresolved relationships, arcing the hero’s inner journey, obstacles, a plot that builds, a steady stream of fresh and unexpected plot developments).

And that’s the advice I’d give all you aspiring screenwriters fighting the good fight. Make sure you have that awesome foundation in your first act. And outline that second act so you know where you’re going. And if the things I listed above about a good second act don’t make sense to you, you need to put in some educational hours and learn what they mean. Because when a second act doesn’t have those things? It falls apart quickly. But at least now you know where the pitfalls lie. And if you know that, you’re one step ahead of everyone else pursuing this crazy medium. Good luck!

Genre: Horror

Premise: During their annual trip to an isolated cabin for Christmas, a family begins to suspect a supernatural force may be haunting them.

About: This script finished high on this year’s Blood List and comes from the writing-directing duo best known for giving us that creepy image of a mom with her face all bandaged up in the 2014 Austrian film, Goodnight Mommy.

Writer: Sergio Casci (current revisions by Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala)

Details: 78 pages

Yeah baby.

The micro-screenplay is baaaaack!! 78 pages! Join the revolution. 78 is the new 100.

Truth be told, I watched this duo’s previous film after seeing that creepy ass trailer that played all over the indie circuit, but came away asking, “Did I just watch a movie or a David Lynch fever dream?” It’s the blessing and curse of foreign films. You’re thankful to see something outside of the American movie system. But by the halfway point you’re always saying, “This writer sure could’ve benefitted from learning inside the American movie system.”

A recent example is Personal Shopper. That movie felt like one of those goofy writing experiments where one writer writes the first 20 pages, passes it on to another writer for the next 20 pages, who passes it on to a third writer who writes another 20 pages, and so on and so forth til the end. The movie LITERALLY starts out as a ghost movie and ends up a murder mystery. For some reason, the word “focus” seems to get diluted whenever it crosses the Atlantic.

So I don’t know what to expect from The Lodge. But let’s check it out.

10 year-old Mia and her brother, 15 year-old Aiden, are prepping to stay with their dad, Richard, for the weekend. While they get ready, you can sense that their newly separated mother, Laura, isn’t happy with the arrangement. And when she gets to Richard’s, he drops a bomb on her. The woman he’s seeing? Grace? They’re getting married.

Laura casually drives home, retrieves a gun, puts it in her mouth, and pulls the trigger.

Cut to a few weeks later where Richard proposes something to the grieving kids. They’ll go stay at their holiday home in the snowy wilderness of Silver Lake and get to know his new fiance, Grace! Oh, Mia and Aiden are just soooooo excited about that! Especially since Richard plans to head out to work for the week, leaving the kids alone with Grace to bond.

Mia and Aiden have good reason to be skeptical of Grace. Richard is a psychiatrist, and Grace was one of his patients. I don’t know what that doctor-patient thing is called. The Hippocratic Oath? Whatever it is, banging one of your patients is definitely not one of the tenants.

Oh, but it gets better. The whole reason Grace needs psychiatric help in the first place is she grew up in some creepy cult where they had you stab people and pour their blood on you during dinner and kill animals and all those other neat culty things. You get the feeling this woman probably isn’t the most stable domino in the row.

After Richard leaves, Grace tries to bond with the kids, but only pushes them further away. Her creepy sleepwalking isn’t helping matters. But where it really falls apart is when everyone wakes up one day to find everything gone. No clothes. No food. No power. No firewood. Grace blames the kids, but as the days pass, it seems like something more sinister is at play. Could the trio have died? Have they all turned into… ghosts?

Man, I loved this script at first. Then hated it. Then loved it again.

Let me explain.

The Lodge had a kickass setup. The mom killing herself was a shocker. Didn’t see that coming. Learning that Richard was a psychiatrist and Grace was one of his patients? Juicy. Grace having that cult past? Loved it. The kids being forced to stay in this remote house with this woman to get to know her? Conflict written all over that setup.

But then the movie got dumb. It became clear that the writers hadn’t thought about this relationship nearly as much as I thought they did. Richard is a non-factor. He leaves the kids here and is no longer a part of the movie – a plot piece so plastic, he should’ve had his own casing. The cult stuff started out cool, but was never expanded on. It felt very generic and vague, the kind of cult activities you would find in any Cult 101 Storytelling Manual.

And Grace was thinner than that 4k TV you bought on Black Friday. Outside of her cult backstory, we know NOTHING about her. The writers make the mistake of not allowing us to get to know the “real” Grace before she goes crazy at the lodge. For that reason, the “crazy” Grace was our normal. And that didn’t work. It would be like if in The Shining, Jack Torrance started off as “Here’s Johnny!” Jack Torrance.

Overall, there was a decided lack of detail in the details. Bathroom mirror scenes where someone has traced crosses in the fog, for example. The “crazy” horror character who’s no longer taking her crazy pills. Little kids speaking to people who aren’t there in the dark. Lots of spooky nightmares assumed to be prophetic. It wasn’t the cheapest form of horror storytelling there is (that would be jump scares), but it was whatever resides just above that level.

However, once the characters began to suspect they were dead, the story found its way back home. It was an interesting story choice. What if the characters in The Others found out they were dead at the mid-point of the movie instead of the end? What would they do? Naturally, you start to go insane, as you suspect that you may be stuck in this house forever. And that’s when this became more than your average haunted house flick.

But it was the subsequent twist and the ending that really placed this in the “must see” category. There are two great scenes at the end, one that involves a woman who believes she’s already dead playing chicken with a fireplace fire, and the other a shocking turn of events when the entire family is brought back together again. A great ending can deodorize so much shitty writing in a script. And that’s what happened here. The ending made me completely forget about all those earlier problems. And solidified The Lodge as a creepy flick that should do a proper job haunting you next October.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Your horror script needs ‘TALK ABOUT’ scenes – scenes that are creepy, weird, odd, unsettling, shocking – the kind of stuff people WILL TALK ABOUT after the movie. If you don’t have those scenes, you don’t have a horror film. You have a compilation of copycat scares from previous horror movies. The Laura suicide scene was unsettling. But it was the fireplace scene, where a Grace who thinks she’s already dead picks up a burning log, stands there with it, and allows it to burn her face, while we cut to the kids upstairs, and hear a screaming Grace slowly burning alive, that really freaks us out. Seriously, one of the first questions you should ask yourself after your horror script (and really after any script), is “What scene will everyone be talking about after this movie?”

Genre: Western

Premise: At the turn of the 20th century, a convict who’s slowly dying from a bullet in his heart escapes prison to find and be with his family again.

About: Westerns are picking up steam as long as they’re not too expensive. Something to keep in mind if you love the genre but have been hesitant to spec a Western out. Today’s script comes from a screenwriter who many believe is a genius despite not being well-known outside of tight 1970s Hollywood circles. Rudy Wurlitzer wrote 1971’s Two-Lane Blacktop and Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid. But his contribution to screenwriting goes well beyond that, as this script in particular, while never made, is said to have been an inspiration to tons of screenwriters. Wurlitzer plays modest when you try and throw the genius tag on him, but there’s no doubt he was a writer to be reckoned with. You can learn more about him in this Vice article.

Writer: Rudy Wurlitzer

Details: 95 pages (undated)

As we move into the age of unlimited content – enough movies and TV shows to keep your eyeballs occupied for 43 lifetimes – it becomes harder and harder to stand out. I distinctly remember a time when you could read a weird story on the back page of a newspaper – a planet that enters our solar system once every 200 years, a freak-house whose oddball occupants never stop building – and feel like you’d struck gold. You had the beginning of a movie idea that nobody else had heard of.

Nowadays, when you run across an idea, you quickly find out there’s been a special about it on the History Channel, it’s been covered in an episode of “Mythbusters,” and it has an entire subreddit dedicated to it with over 170,000 subscribers. With original concepts becoming harder and harder to come by, how in the world does one stand out?

The answer is VOICE. Ideas have been democratized, but you still have a monopoly on your point of view. If you can tell a story in a way that it hasn’t been told before, YOU become the concept.

Zebulon is said to be one of the most influential scripts ever written in Hollywood, with many writers claiming it as an inspiration. The story goes it never got made because so many other writers stole from it. I’d heard very little about Wurlitzer before being told of Zebulon, so I was curious to see how juicy and unique his voice was. Time to put my ear close to the paper.

It’s the beginning of the 20th century and mountain men are being phased out. It used to be you could set up a bunch of traps in the mountain, get yerself some furs, sell’em up at the Trading Post, and be set for the winter. Not so this year, Zebulon Pike learns. When he and his Pops go up to the Trading Post, they’re told to suck it, and Pops don’t take it so well. A gunfight ensues, Pops dies, a Post worker is shot, and Zebulon is sent to prison for a couple of decades.

Zebulon spends seven of those years trying to escape so he can get back to his family, but fails every time. When he finally breaks out during road construction duty, he takes a bullet in the chest, and is told by a doctor that it’s wedged into his heart. They won’t be able to take it out, so the bullet will slowly kill him. At most, Zebulon’s got weeks to live.

That’s enough time to get back to his wife and son, so off Zebulon rides, back home. Meanwhile, the Captain of the prison, a former army general who was stationed to the prison after an act of cowardice in battle, teams up with an overzealous alcoholic two-bit novelist named Stebbins, who believes this story of tracking and capturing an escaped outlaw is his ticket to the big-time.

Zebulon is able to stay one step ahead of his pursuers and make it back to his wife, only to learn she’s remarried. With only days left to live, he convinces her to take one last journey with him to find their son, who’s since flown the coop and, rumor has it, is covering up a big secret. Will they make it to him in time? Or will the bullet… or the Captain… get to him first?

Only in my line of work do you get to read about a prison in the year 2100 one day and a prison in the year 1900 the next. Pretty damn cool!

Back to that voice conversation. Here’s the thing. After reading this script, I’ve determined that it’s not the version that everyone fell in love with. The version everyone fell in love with was about a man who gets shot and wanders the world between the living and the dead.

Indeed, that sounds way trippier and cooler than what I read here. And it reveals a conversation that never goes away in Hollywood. Everyone says they want “voice.” But the closer a project gets towards production, the more people in charge want to normalize it. That seems to have been the case here, turning Zebulon into a decidedly straight-forward endeavor.

And the thing was, you could feel its potential bursting at the seams. I can only imagine what an unrestrained Wurlitzer would’ve done with Stebbins, the novelist, who was hilarious even in a restrained role. I loved how, when Zebulon shot and killed a single man to escape, Stebbins turned him into six men for his story. Or when the group was attacked by a single Indian while sleeping one night, Stebbins began counting the money as he transformed the Indian into an entire tribe. This didn’t even begin to explore the strange particulars of Stebbins’ personal life, such as he and his bizarre wife’s plan for her to have sex with the Captain.

Outside of Stebbins, though, this draft of Zebulon is about as straight-forward as it gets. A guy goes to be with his wife before he dies. There was a GOAL (get to the wife) and URGENCY (he’s going to die any day now) but no STAKES. He and his wife’s relationship hadn’t been set up well before the Trading Post skirmish, so I didn’t give a damn whether he got to her or not. Knowing what I know now about the original draft, I can see that the goal, stakes, and urgency were never meant to drive the script in the first place. It was the weirdness of slipping in and out of the living and the dead world that was Zebulon’s “strange attractor.” Once you take that away, it’s just a “Get from Point A to Point B” movie.

Those looking to see that original draft, though, can still get a taste of it in Jim Jarmasch’s “Dead Man,” which is basically a ripoff of Zebulon. I can now say that I’ve read another script that, in retrospect, was majorly influenced by Zebulon. That infamous Gladiator 2 script I reviewed by Nick Cave.

If there’s anything I learned about voice from this later draft of Zebulon, it’s that Wurlitzer seemed to be ahead of the curve with his style. He writes with a clarity and succinctness that most writers didn’t begin using until the 90s (this script was written in 84). In the Vice article I linked above, someone points out that Wurlizter is able to convey big ideas in a down-to-earth way, and I agree. The script was very accessible and easy to read.

I do wish I’d read the original draft of Zebulon though. It seems like it was more fun. Even if this was a serviceable approximation.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is another TRANSITION PERIOD script, which means the writer focuses on a time when things were changing in the world. Mountain Men, who used to be able to live off the land, were now being phased out. Transition periods are great to build stories around because transition means change and change means conflict. Conflict is the lifeblood of entertainment, so if you can infuse conflict into your story before it even begins, your story’s going to start with a bang. And that’s exactly what happened here. When the Trading Post wouldn’t pay him for his furs like they always had, a standoff ensued, people were killed, resulting in our hero being thrown into prison.