A quote doesn’t always become part of the screenwriting lexicon because it deserves to. A lot of times, a quote becomes famous simply because it sounds good. And there’s nobody better at creating sexy-sounding quotes than writers. I mean, that’s their job, right? So today I wanted to sift through some of the sexiest writing quotes throughout the years and determine which advice is actually good, and which you should ball up and toss in the wastebasket.

“If you want to send a message, go to Western Union.” – This was uttered by a famous studio head in the Golden Age of Hollywood in response to screenwriters who argued that their stories should be about more than surface-level entertainment, that their movies should actually contain a theme, or “message.” Here’s the thing about this piece of advice. I think what the studio head was referring to wasn’t themes in screenplays. He was responding to bad writers clumsily executing over-the-top themes in screenplays. Of course your script should be about something. But if you’re on-the-nose and clumsy with the way that theme is executed, people aren’t going to respond well. As is the case with most aspects of screenwriting, you must integrate the component invisibly.

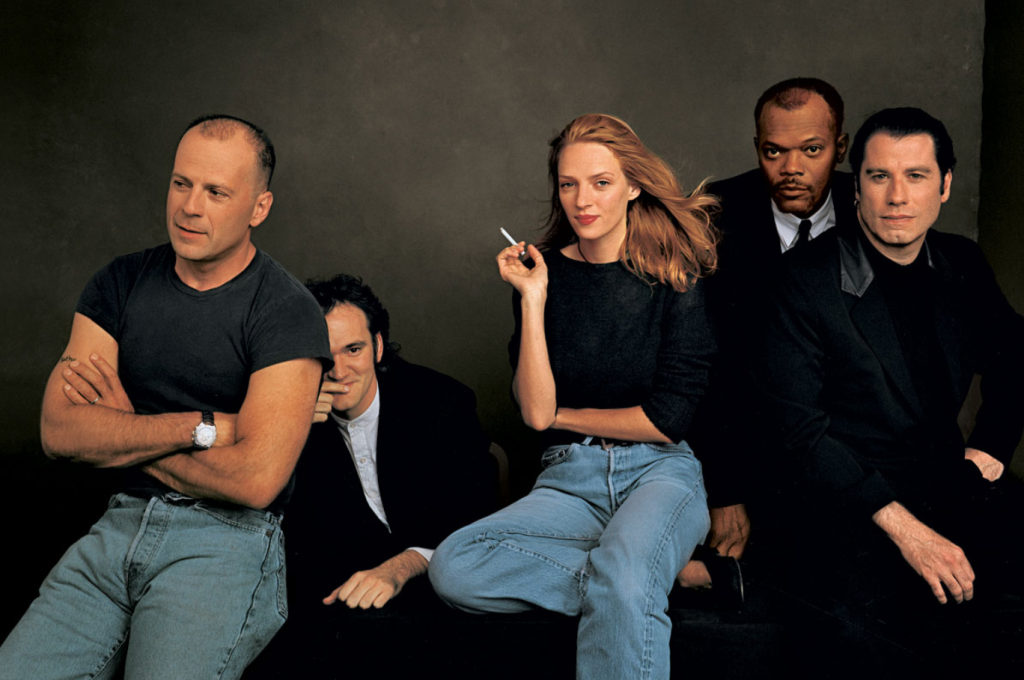

“Every story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. But not necessarily in that order.” – This was one of the most famous screenwriting quotes to come out of the 90s, and it was born out of the success of Quentin Tarantino, specifically Pulp Fiction. The advice itself is fine. But it set a bad precedent to aspiring screenwriters, encouraging them to write these wild out-of-sequence narratives before they knew how to tell a simple story. Who cared about a narrative spine, stakes or compelling characters when you could rapidly cut back and forth between disparate storylines? As such, I would be wary of this advice. Learn to tell simple stories first and then move on to more complex narratives like Pulp Fiction.

“Kill your babies” – This popular piece of advice has been around for half a century, and the idea behind it is simple. Writers – especially beginner screenwriters – believe that every thing they write down on the page is gold. As in, once it’s there, it cannot be erased. Ever. To be a great screenwriter, you must be willing to eliminate that character, that scene, that subplot, that dialogue exchange, if it doesn’t keep the story moving forward. This is the essence of “Kill your babies.” You have to be a harsh editor. This advice was relevant when screenwriting was invented, and it will be relevant for as long as screenwriting is around.

“A professional writer is an amateur who didn’t quit.” – I remember when I first heard this quote and it kind of blew my mind. You can’t fail if you never give up. Death is literally the only thing that can stop you. But I do think the quote is dangerous. There are people who are 15 years into their pursuit of screenwriting (or whatever artistic endeavor they’re pursuing) who aren’t living productive lives. You have to be smart about it. As you get older and “adult” responsibilities creep in, you shouldn’t be hedging every aspect of your life on selling that big screenplay. It’s cute at 25. Not at 35. However, the awesome thing about writing is that it’s the cheapest of all the artistic pursuits. So make sure you’re giving the rest of your life ample attention and squeeze in time to write after those duties are over. As long as you love to write, there’s no reason to stop.

“Always ask yourself, what’s the worst thing I can do to my hero right now? Then do that.” – There are a lot of variations of this quote. Another comes from Kurt Vonnegut: “Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them—in order that the reader may see what they are made of.” One of the biggest mistakes young writers make is that they’re too kind to their protagonists. Every aspect of their journey is too easy. You gotta put your protagonist through the wringer, man! For the exact reason that Vonnegut points out. We only find out who a person truly is when they’re faced with adversity.

“If there’s a problem in the third act, it’s because of an issue in your first act.” Of all the famous pieces of screenwriting advice out there, this is one of the ones I like the least, mainly because it’s vague. And there’s no quicker way to confuse a newbie screenwriter than to give them vague advice. I think what the advice is trying to say is that if something isn’t working in your third act, it means you didn’t set it up properly. For example, if your hero kills the dragon with some potion he randomly found two seconds prior, that would’ve worked better had you set the potion up earlier. But it doesn’t mean you needed to set it up in the first act. You could’ve just as easily set it up in the second act. So the advice here is more, “If something isn’t working in your climax, you need to set it up better somewhere.” Of course, that doesn’t sound as flashy, which is one of the problems with famous quotes.

“If you show a gun at any point in your story, it must be used later.” – I agree with this one. And note that “gun” is a stand-in for any weapon. Crossbow, hunting knife, bomb. And this is mostly due to the way we’ve been conditioned by cinema. It’s happened so many times in movies before, that if you DO show a weapon and don’t use it, it’s confusing to the audience. I remember reading a script once where the writer went to great lengths to highlight this sword on a wall. He described every crevice of the thing. I was convinced it would be used later to decapitate someone. Nope. It was never mentioned again. Drove me crazy.

“If I have anything to say to young writers, it’s stop thinking of writing as art. Think of it as work.” This one comes from Paddy Chayefsky and it’s something I’ve come to appreciate more as I’ve grown older. Screenplays only reach their potential during rewrites. And, unfortunately, when you’re on your 7th draft and nothing about your story is fresh or fun to you anymore, busting the computer open isn’t as easy as it was during that stream-of-conscious rollercoaster ride of a first draft. The good writers buckle down and they get the work done, even when it’s not fun. So I totally agree with Paddy here.

“Write drunk, edit sober.” – I don’t know who said this (was it Hemingway?) but this is the very definition of what’s wrong with famous quotes. This is such a sexy quote and so fun to say but it’s terrible advice. While writing drunk is fine to do every so often, you do not want it to become a crutch. You’ll be convinced that the only way you write good stuff is to get wasted, and that’s not sustainable. However, I do like the cousin of this quote, as it captures the spirit of it in a much healthier way: “Write from your heart; rewrite from your head.” Be non-judgmental when you write. Let yourself feel things without right-braining them to death. Then, when it’s time to rewrite, bring a more logical assessment to the writing.

“Grab’em by the throat and never let them go.” – This comes from Billy Wilder and I think it’s one of the most important pieces of screenwriting advice you’ll ever hear. Too many writers put the burden of investment on the reader. “You owe me,” is how they look at writing. No no no no no. Readers don’t owe you anything. It’s up to you to keep them invested. And the second you drop that ball, whether it’s on page 1 or page 50? They’re gone. They’re done with your script and they have that right. You want to grab your reader with the very first page and then every subsequent page, ask yourself, “Do I still have them?” If you don’t think you do, rewrite the scene until the answer is yes. That doesn’t your script should be one long action set-piece. You can use mystery, suspense, foreshadowing, conflict, dramatic irony, confrontation, anticipation, an intriguing new character, and, sure, a kick-ass action scene we’ve never seen before. You have hundreds of tools available to yourself. You are in control of whether your scenes are good or boring. Never take that for granted.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. I highly recommend not writing a script unless it gets a 7 or above. All logline consultations come with an 8 hour turnaround. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Genre: Horror/Action

Premise: When a discarded top secret military weapon resurfaces on a research ship, the crew must fight for their lives to survive the bizarre technology.

About: Cary and Chad Hayes have become Hollywood’s go-to A-List Horror writers, scripting both The Conjuring and The Conjuring 2. But that success didn’t come overnight. The brothers wrote in television for a dozen years before getting their first shot at the feature world (2005’s House of Wax) and then went almost an entire decade before they had their first major breakout hit in The Conjuring.

Writers: Cary and Chad Hayes

Details: 104 pages – 2011 draft

I’ve always wondered, how do you make a blob scary? It’s a blob, the goofiest monster ever. It doesn’t even have a personality. It’s a blob.

I like reading these scripts, though, because I’m always curious what writers pitched to win these “no-win” assignments.

For those of you who will be lucky enough to break into this business, you’ll be asked to pitch no-win takes on assignments all the time. You could say that the writers who last the longest in Hollywood are the ones who consistently come up with solid takes on bad ideas.

Remember, it was Charlie Kaufman who, tasked with adapting a book about flowers, came out the other end with Adaptation.

I personally don’t believe it’s possible to write a good Blob movie. But I’m ready to be proven wrong. Let’s see if the Hayes brothers pulled it off.

Shannon Cole is a member of a research team on the high-tech vessel, “Indigo.” Besides researching ocean life, Shannon also likes researching her hot Navy boyfriend, Colin Hawthorn, who she’s constantly trying to sneak Skype sessions with whenever possible. The two discuss how it’s only a matter of time before they can be together, sans ocean in the way.

And then a plane crashes next to the Indigo. And not just any plane, but a military plane. Members of Shannon’s team are able to save the sole survivor, a dude named Steve Walker, but they sense something is off right from the start. Especially when Steve hightails it off the ship. As in, he leaps off and starts swimming away. What in the world would cause a man to swim into an endless ocean as opposed to stay on a ship?

Answers start coming in the form of the NAVY, who radio Indigo to tell them to watch out for this Walker fellow. Oh, and to avoid any gelatinous masses that happen to have snuck on the ship. Oops, too late for that. The secret weapon that Walker stole, and which was responsible for the crash, has made its way onto the Indigo.

Once Shannon and her crew spot this thing, they begin attacking it. But it’s pointless. There’s no way to actually destroy gelatin. It just eats up their bullets, their weapons, and eventually, their bodies.

Shannon calls for help from her nearby NAVY boyfriend, but he tells her this call is above his pay grade. The military is so terrified of this blob weapon that they’re going to let it do its damage and, hopefully, disappear forever afterwards. That means Shannon and her crew will have to figure out how to defeat this thing on their own. A task they’re realizing may be impossible.

Okay, let’s approach The Blob the way any screenwriter tasked with adapting this idea would. You’ve only been given one quota: A “blob.” You can do anything you want with that, as long as there’s a blob. What do you do?

The Hayes’ brothers opted to place the blob on a ship. On the plus side, you’ve created a classic horror scenario. A monster. A contained location. A bunch of people stuck in that location.

But the first thing I asked was, “Is a research ship really the most interesting location for this concept?” Not really. You’re limited, pretty much, to your blob squirming around the hallways of a ship. I’m not sure if you’re getting the most out of the idea there. Had the Indigo been researching something that could’ve conflicted with the blob in some way, that might’ve been cool. But it didn’t. In fact, I was never clear on what this ship was researching.

Specificity guys. You have to think in terms of specifics, not generalities. Because there was nothing unique on this ship, nearly every scene was identical. People hiding in rooms. The blob banging on the door. Sometimes getting in. A battle would occur, they’d go to another room. Variety isn’t only the spice of life. It’s the spice of screenwriting. You have to differentiate your scenes. And because all the elements here were so generic, there wan’t much opportunity to change things up.

Also, the one advantage you have with a villain as unique as a blob is that you can look for things that only this specific “monster” can do, and play around with that. Take Freddy Kruger. He can haunt your dreams. So you can write a lot of cool scenes where Freddy is stalking you in your dreams, where you’re not sure if you’re asleep or awake, where he’s luring you to sleep – the kind of things that ONLY THAT CHARACTER offers to the story. That’s part of the fun of screenwriting, is finding those unique avenues that only your specific concept can provide.

But the blob never gave me that. There was one moment early where a character gets swallowed up by the blob and we watch him see the world through his POV as he’s being digested. But that was pretty much it. Otherwise it was just a blob banging away on doors and eating folks. Any monster can do that.

The best opportunity for a memorable scene came when the crew gets stuck in the shark lab. A tank full of sharks? A blob. Your team can’t leave the lab? The possibilities are endless, right? What if the blob keeps banging on the door and the shark tank starts cracking. Bang. Crack. Bang. Crack. The group realizes that either they stay in here and get eaten by sharks or they take their chances with the blob.

OR maybe the blob eats the sharks, which are swimming around in its gelatinous mass, some of their shark heads sticking out, chomping like crazy to get away, and our team now not only has to deal with a killer blob, but a killer blob of crazed sharks!

No, we don’t get any of that. Our team simply looks up after a moment and notices that all the sharks are gone. The blob has eaten them. And that’s the end of our shark lab scene.

I don’t think you can write a blob movie that isn’t a comedy. This is something you have to build a goofy premise around and then really have fun with it. I could see, for example, a group of people getting caught inside a 50s movie universe. They come to some deserted town, where they’re attacked by things like the Fog and the Blob. And you just get goofy. I could see the Blob swallowing people up, but then releasing them out later, and they become these slime-soaked blob marionette zombie things that do the blob’s bidding. Shit like that.

Trying to turn a blob into a serious action movie? I don’t see any audiences being interested in that. Feel free to offer your own blob takes in the comments section. I’m curious if anyone can actually pitch a good idea off of this.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I learned that if you have a weird starting point – like a blob – you need to embrace that weirdness and get weird with it. To try and take a weird concept like this into straight territory is a bad idea.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from Blood List) A monster-obsessed kid witnesses a murder in his neighborhood and must defend his house when it comes under siege by the killers.

About: Today’s script finished #2 on the 2017 Blood List, Kailey Marsh’s list of best unproduced horror, thriller, and sci-fi screenplays. A familiar script to Scriptshadow readers finished at the top – MEAT. Nightlight sold to Sony earlier this year.

Writers: Chris Lee Hill & Tyler MacIntyre

Details: 92 pages

Hollywood’s confused right now.

After September unleashed a record-breaking box office, October’s done the opposite. Nobody’s going to see anything this month.

This is proof-positive that there isn’t some overall declining interest in movie-going, as some doomsday sayers have attempted to propagate. But rather – if you come out with movies that look good (September), we’ll go and see them. If you come out with movies that look bad (October), we won’t. I mean, who’s going to see a movie called “Suburbicon?” Is that, like, what happens when a suburb transforms into a robot?

A more accurate box office analysis may be the one that’s most recently making the rounds – the Rotten Tomatoes Theory. Under this theory, Rotten Tomatoes scores drive the majority of moviegoers’ decision-making. This would line up with my above hypothesis that people go to see good movies and skip bad ones.

Who knows what the ultimate truth is? I just like tweaking Hollywood every once in awhile. Despite all of their research and models, they still can’t find that elusive sure proof formula.

So would today’s script, Nightlight, land in the September of the October category of movie? Let’s find out.

It’s 1989. 10 year-old Stanley is a bit of a misfit. He’s got a stutter. He spends all his time looking up the Lochness Monster and Bigfoot. Everyone thinks he’s a weirdo. To pour salt on the wound, Stanley’s parents are recently divorced and he’s still learning how to live alone with his mom and sister.

One night Stanley sees, what looks like, his female neighbor getting attacked by men in her home. The curious Stanley creeps across the street to check it out, only to watch as, indeed, a couple of men kill the woman. He’s spotted by one of the prowlers, who sees him run back to his house across the street.

When Stanley tries to tell his mom what happened, she thinks it’s all a result of his overactive imagination. The family then gets a call from the police, who inform Stanley’s mom that her daughter’s troublemaker boyfriend has been picked up, and that he was hoping she and Stanley’s sister could come pick him up.

This is a ploy by the prowler, of course, who moves in to the house the second the mom and sister leave. However, the prowler soon learns that Stanley is craftier than he looks. Stanley’s able to move around inside the house’s many hiding spaces (laundry chutes and such) to avoid the intruder.

Stanley’s plan is to play this game of hide and seek until his mom and sister get back. But when the prowler becomes desperate to tie up this loop, Stanley will have to use all of his craftiness to get out of this nightmare alive.

I should preface my breakdown by saying I’d sped through the logline and thought I was reading something different. I assumed this was going to be Home Alone but with monsters trying to get into the house. I thought that was a really cool idea. When I realized it was just one guy trying to get in, I was disappointed, and that definitely colored my reaction.

Regardless of that issue, this was a weird read. There were many moments where I’d come across a scene and say, “Wait, what?” For example, Stanley’s mother sends him up to clean leaves out of the roof gutters. As in, on a ladder.

Wait, what??

This would be dangerous even for an adult to do. Yet Stanley’s mom is sending her ten year-old – a boy we’ve established is frail and weak no less – to clean out gutters on the roof?

Or there was the moment where the “police” call to have Stanley’s mom come pick up his sister’s boyfriend. Not only were we never informed that Stanley’s sister had a boyfriend in the first place. But why would it be up to the unrelated mother of a boyfriend to pick this guy up? There was a lot of this, leaving me constantly scratching my head.

There were lots of missed opportunities, as well. For example, at a certain point, the prowler makes it clear to Stanley that when his mom and sister get home, he’s going to kill them. This added a new wrinkle to the problem. Up until that point, Stanley could just keep hiding. However, knowing his mom and sister would be in danger when they got home, this meant hiding was no longer an option. He’d have to take this guy on. I thought that was a great choice.

However, it’s negated the second we find out that the mother and sister are coming home with a police escort. So they’re actually in no danger at all.

But the biggest missed opportunity was in how Stanley fends off the attacker. It’s all with basic generic tricks like clever hiding places and such.

When you write a story like this, it’s the perfect opportunity to use WHAT’S UNIQUE ABOUT YOUR HERO to help him survive. Stanley is set up as this monster expert at the beginning of the movie. It’s the reason everyone thinks he’s so weird. So what better better way to save your life than with the knowledge that, up until this point, everyone’s used to make fun of you?

What would the Loch Ness do? What would Big Foot do? Their unique abilities could have inspired Stanley to keep outwitting the intruder.

Something that could really help this script is more attention to setups and payoffs. Things like the sister having a boyfriend come out of nowhere instead of being properly set up ahead of time. And because these moments are major pillars in the advancement of the plot, it’s too easy to question them. Ditto the ending, which I won’t get into, since it’s a spoiler. But a character we’d never met until that point has a huge influence on the climax.

Now some of you may ask, “Well, Carson, why did this sell when my script is stuck in Nobody Gives a Shit Land?” Here’s the thing. Despite the problems I’ve listed above, we still have a MOVIE here. What I mean by that is we still have a clear situation with high stakes and lots of conflict, and an easy-to-market concept. Those things matter.

Whenever people complain to me that bad scripts sell while their great scripts are stuck on the shelf and I actually read those scripts? They’re not even at a level where you can compare them. They might be obscure tone poems. They might have second acts that deviate completely from the setup. They might not have a single marketable component to them. At least Nightlight is a movie, flaws and all.

It was an interesting reading experience nonetheless, even if it wasn’t my cup of hot cocoa.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the easiest ways to strengthen a shaky plot point is to set it up earlier. For example, all we needed to do to strengthen the forced plot point where the fake police lure Stanley’s mom and sister out of the house was to SET UP an earlier fight between the sister and her boyfriend. Now we’ve seen the boyfriend’s volatility. Now we KNOW the boyfriend. This way, when we learn the boyfriend is in jail, we’re like, “Oh, of course he is. That guy was crazy.”

Are the Duffer Brothers trolling Netflix and the rest of us?

I want you to put your Scriptshadow Imagination Cap on. Not the big one. Just the regular-sized one. This won’t require much of a leap. Got it on snug? Okay, I want you to visualize something for me. I want you to imagine a movie about four guys living in Los Angeles. Let’s call it: The Reservoir Club. Our main character – we’ll call him DAVE – likes this girl who works down at a 50s soda shop on the corner. Every weekend, the two compete in the shop’s dance competition. The place is called Dirty Mack Tim’s.

Dave’s roommate, JOHNNY, has had it rough. He lost his memory in a car accident. In fact. He can only remember things for 36 minutes at a time. So he’s started keeping tattoos on his body to remind him of the things he’s forgotten. NICK, who lives down the hall from the two, has this really fucking cool business idea. He wants to use human fat to create the single greatest shampoo in the world. He thinks it will make bank.

Oh, and let’s not forget LESTER. He’s a gimp. Walks funny. And the cops think he knows something about a recent murder. A gun-runner named Shawn Joze.

Now imagine if we lived in a world where all of this was packed into a single movie, and nobody actually complained that all of these things are giant plot points from famous 1990s movies, but rather they heaped praise on the film as a wonderful reminder of how good that period of movies was.

This is the dilemma I’m posed with when people ask me if I like Stranger Things.

Objectively speaking, the hit Netflix show does a lot of things right. The casting is top notch. The production value is great. The directing is strong. Even the writing is good. I particularly liked what they did with the plotting in the first season. They wrote 8 shows instead of the traditional streaming trend of 10. This allowed them to lay their season out like a feature screenplay, which has 8 sequences (2 in Act 1, 4 in Act 2, and 2 in Act 3). Episodes 1 and 2 became setup, Episodes 3-6 conflict, and Episodes 7 and 8 the resolution. And it works. The season never drags.

But, I mean, come on. Is there ANYTHING in this show that’s actually original?? Like even a single shot? Watching Stranger Things is like watching Steven Spielberg and Stephen King hang out and talk movies.

“Oh, that’s my shot from Close Encounters.” “Hey, they based 11 on Drew Barrymore from Firestarter. Neat!” “Didn’t I direct that exact same scene in E.T.” “Pretty sure there are about 50 scenes in here stolen from E.T. Steve old buddy.” “Cooool! Gremlins. But with a lizard!” “OMG, it’s literally like I’m rewatching Stand By Me.”

The other day, I saw an article titled, “11 Movies that Inspired Stranger Things.” I’m sorry. But if you have ELEVEN movies that inspired your movie/show, you’re doing something wrong. I don’t know about you guys. But when I release something, I want people saying, “I’ve never seen anything like this before.”

Still, the show is a hit. People love it. There’s no doubt about that. And that leads us to the question of the day: What can we learn from Stranger Things that can help us write our own hit TV show?

Well, each TV show is its own ecosystem. It’s a hit for its own reasons. But we may be able to steal a few tips from the show. I’m sure the Duffer Brothers won’t mind.

For starters, they integrated a conceptual trope that’s as rock solid as tropes get in hooking viewers – a missing kid or missing woman. There isn’t a person on this earth who doesn’t feel something when a helpless human being goes missing. So this usually gets people on board right away. At least for a couple of episodes.

That means you’ve got about 90 minutes to convince the viewers to stay with you once the missing person novelty wears off. Which means you have to use those 90 minutes judiciously. What should you focus on?

If you answered THE CHARACTERS you win a Scriptshadow cookie, which you can order with extra GSU if you so please.

Those 90 pages (or 2 episodes) need to be used to create AT LEAST half a dozen characters we fall in love with. Maybe because they’re brave. Maybe because they’re flawed. Maybe because they’re mysterious. Maybe because they’re funny. Maybe because they’re in love with a girl at school and we just HAVE to keep tuning in to see if they’re going to get her. Every time you create a character you should be asking yourself, “Why would an audience care about this person?” If you don’t have a good answer, keep working on that character.

Simultaneously, you should be establishing CONFLICT inside of the characters’ relationships. A mother and son who never get along. A sibling rivalry. Two girlfriends who both like the same guy. A marriage on the rocks. A patient (11) who’s sick of doing everything the scientist tells her to do. A military vet who doesn’t trust ANYONE in town. It doesn’t mean everyone should hate each other. Storytelling necessitates that some relationships start out strong. But if you aren’t exploring fractures in relationships, it’s one less reason for us to check back in.

To demonstrate the importance of this, think about an old friend you occasionally meet with. Imagine sitting down with that person over coffee and asking how things are going. “How’s your family?” “Great!” “How’s your work?” “Can’t complain. We just won a big case at the firm” “Last time we talked, you and your boyfriend were having trouble. How are you now?” “Oh, we’re wonderful. We communicate a lot better and I’ve learned to give him his space when he needs it, which has dissolved almost all the tension in our relationship.” And so on and so forth for 45 minutes.

How bored would you be in that conversation? Life is struggle. It’s conflict. It’s obstacles. Yes there are good times, but there are always tough times mixed in. Drama should be a reflection of that. If everybody’s happy with each other in your show, I guarantee you we’ll be bored as shit.

And remember not all conflict needs to be black and white. There just has to be an unresolved nature to it. One of the most-talked about characters in the first season of Stranger Things was Barb, the awkward best friend of Nancy Wheeler. When Nancy starts getting attention from popular bad boy, Steve Harrington, Barb tries to be supportive but senses that, if Nancy and Steve hit it off, her friendship with Nancy may be in danger. So Barb warns Nancy (“He just wants to have sex with you”) and attempts to guide her away from the “dangerous” Steve. But let’s be honest. It’s not that she feels Steve is dangerous. It’s that she feels she might lose her best friend.

As viewers, it’s in our nature to want to see conflict resolved. So we’ll stick around until that happens. As old conflicts get resolved, you’ll be weaving in new conflicts. And when those conflicts get resolved, you’ll be introducing new characters, which will allow you to create conflicts in new relationships (this is what they did this season with the red-haired girl and her Karate Kid villain brother).

However, while character and relationship conflict will be a major priority, you can’t completely abandon plot. Plot, you have to remember, GIVES YOUR CHARACTERS PURPOSE. A character who must figure out how to find a missing boy will always be more interesting than the same character who doesn’t have to do anything. So you’ve got to keep introducing new plot points to get your characters out there doing things.

Stranger Things does a pretty good job with this. For those of us who’ve seen all the 80s movies, these plot points may not be all that original. But to people who haven’t, they must seem beyond cool. Eleven is cool. The Upside-Down is cool. The secret lab stuff is cool. I’m not going to fault the Duffer Brothers for using old tricks on new dogs. I’ll never forget how devastated I was when I watched Escape from Alcatraz many years after seeing the mind-blowing Shawshank Redemption and realizing that Shawshank stole the “hide the tool in the bible” trick. The Duffer Brothers are just doing the same thing on a mass scale.

There are probably other things at play behind Stranger Things’ success. It was one of the first genre streaming projects to use the television format to create one giant movie. Imagine if Stephen Spielberg was able to make a 5 hour version of Close Encounters? I think that would’ve been pretty awesome.

Stranger Things is also distinctive in that it’s probably the most charming show I’ve seen all decade. There’s something so warm and cute about it that no matter how hard you try, you can’t stop smiling. And maybe that’s enough.

Genre: Horror

Premise: A man’s life starts to unravel when he undergoes an experimental form of hypnosis to recall what he saw during a near-death experience.

Why You Should Read: The concept of this script is very loosely based on a true story. I actually knew someone who survived a near-death experience and he hasn’t been the same since. When I asked him about it he told me he didn’t remember what he saw but I had the strange feeling he actually did and was holding back for reasons I don’t know. Since the incident he’s left his family, quit his job and went off the grid. I honestly don’t know where he is now. — I’m a huge fan of horror movies and I believe “dread” is key component is some of the best of them. Any writer can throw in some good scares here and there but building up real dread for the characters and the story on a whole seems to be overlooked in many scripts I read these days. I feel like I’ve been able encompass this with BLACK BOX without losing the pace of the story. It’s a fast entertaining read with some big scares wrapped inside an intriguing mystery. I hope you’ll take the time to check it out and look forward to your honest feedback.

Writer: Stephen Herman

Details: 100 pages

I don’t know what’s the bigger horror film on the docket this weekend, Jigsaw or Suburbicon. Bada-BUM! No, but seriously. I don’t know what’s scarier. Pennywise or George Clooney thinking he can direct satire. BADA-BUM! I’ll be here all night. Try the veal.

No, but seriously. I’ve been looking forward to today all week! Black Box bowled down the competition in last week’s Amateur Offerings, so much so that it looked like we had another Amateur Offerings success story on our hands – an event that’s becoming more and more frequent, thanks in big part to you guys.

I was only worried about one thing going into the script – the dream aspect (the hypnosis). Putting dreams in the hands of an amateur writer is a bit like putting the recipe for a Gino’s East deep dish pizza in the hands of a line cook. It’s not like that cook won’t one day become a great chef. But it’s hard to bake the most luscious crust in the world when you’re still learning where the pans are located.

One of the biggest challenges for amateur writers is narrative structure – for their script to stay focused and purposeful all the way through. Dreams are anti-structure and therefore encourage the writer to move away from purpose. As a result, they’re the script’s undoing. The narrative becomes a loosely connected series of tripped-out scenes sewn around shaky logic. Let’s hope that didn’t happen with Black Box!

40 year-old Nolan Wright is recovering from a recent car crash that killed his wife. The crash, which left Nolan dead for six minutes, resulted in brain damage so severe that it’s gradually stripping away Nolan’s memories. Lucky for Nolan, he still has his beautiful young daughter, Ava, by his side. She’s the one thing keeping him going.

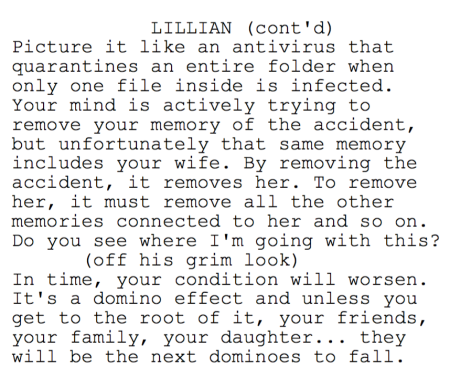

However, Nolan gets word that if he doesn’t do something soon about the brain damage, the world will start slipping away from him, including Ava herself. This forces Nolan to seek out Dr. Lillian Grey, an experimental doctor who’s on the cutting edge of memory recall. Lillian believes that if Nolan can remember everything that happened during those six minutes he was dead, he can permanently heal the brain and eliminate his amnesia.

This becomes increasingly important when Nolan loses his journalist job and the Department of Children and Family Services start sniffing around, trying to decide if Nolan is a fit enough parent to take care of Ava.

Lillian’s therapy involves a literal black box that you plug yourself up to. The box helps you go into the deepest levels of your subconscious, and this is where Nolan relives his crash. On that first trip, he finds footsteps near his crash, which he follows into the woods. It’s there that he sees a dead man hanging from a tree who quickly drops and starts walking towards Nolan backwards.

Nolan’s so freaked out that he pulls himself out of the hypnosis and says he’s never coming back. But in order to keep his daughter, he has to come back, and in a series of hypno-trips, Nolan will learn that this journey extends beyond him, and to a number of people who also cheated death.

Man, I can see why everyone voted for this.

The first act is AWESOME. There was an assuredness in the writing that I wasn’t prepared for. Assuredness is a key trait of professional writing because professionals are better at knowing where their story is going. When you know where your story is going, you write with confidence. I mean, listen to how clear, dominant, and assured the character of Lillian is when she brings Nolan in.

With amateurs, there’s more of what I call the “shiny object” approach to writing. They’re often trying to figure things out on the page. Every once in awhile they’ll see something that’s interesting (a “shiny object”) and it’s like, “Ooh I’ll follow this for awhile.” Black Box didn’t have that.

Well, at least at first.

Once we got 15 pages into the second act, the tight narrative began to unravel. I could feel Stephen being tempted more and more by the shiny object, until it got to the point where it was the only thing left. The biggest problem was in explaining what was going on with Nolan.

I see this a lot. Whenever we come up with a high concept idea, there’s this pressure to construct a big flashy reason for what’s going on. So in Black Box, we find out that there are other people who also had near death experiences, and then there’s somebody who’s using these people to take their bodies and live in them… or something, because once you’ve gone through death, it’s easier to take your body?

To be honest, I barely understood it. And that’s the thing. When you try and get too big, you come up with a convoluted rule-set that’s hard to understand. And because we don’t understand it, we stop investing, we stop caring, and by the end, we don’t really know what’s happened. I know I didn’t.

Honestly, the issues in Black Box take us right back to yesterday. This shouldn’t have been about a flashy serial-body-stealing near-death-experience conspiracy. It should’ve been about characters. And this is my plea to amateur writers out there: stop trying to write the most-blowing mind-bending script ever. Just focus on the characters!

There are some good characters here. Nolan is great. The stuff with the car crash all felt honest and authentic. Ava is great. Lillian is great (minus her turn at the end). Gary is okay but could also work. The social worker who cares “a little too much” is great. Yet they get lost in this silly weird plot that doesn’t make any sense.

I mean at one point we have an ancient shaman killing a dog and becoming part of its soul. This isn’t what I signed up for.

I would strongly recommend dialing back all of the weird shit and focus more on the real-life character journeys. Keep the hypnosis scenes grounded. Have a simple and clear set of rules for what happens inside each hypnosis. Keep the mystery itself simple. Something that happened around the car crash. Don’t bring in people who died 50 years ago halfway across the world. We don’t care about them.

I know I sound like a broken record, guys. But simplify simplify simplify simplify simplify simplify simplify simplify blah blah blah a million more times.

Every time you overcomplicate things, you’re destroying your story.

Script link: Black Box

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I love it when HUGE stakes can be conveyed simply and powerfully. Here, it takes just a single line to set up the stakes for the entire movie. It occurs when Lillian explains why this therapy is so crucial for Nolan: “In time, your condition will worsen. It’s a domino effect and unless you get to the root of it, your friends, your family, your daughter… they will be the next dominoes to fall.”