Search Results for: James bond

It’s the LAST DAY of White Lotus Is Amazing Week. I know that some of you are going to go in a deep depression after this. Just know that there are outlets where you have support. White Lotus Discussion reddit threads. Youtube interviews with the cast and crew. I’ll be publicly recreating scenes from the show at Griffith Park this weekend for anyone who wants to stop by. Don’t worry, the Steve Zahn opeing shot will be censored. That was one of the first things the Los Angeles Public Parks Department demanded when I applied for the permit. But sadly, starting Tuesday, we’re going back to a White Lotus Free Zone. Feel free to pay your respects in the comments section.

Our final topic of discussion is going to be the intersection between plot and character.

One of the common criticisms I’ve been hearing from the WLHA (White Lotus Haterz Association) is that there’s nooooooo plooooootttttttt. Nothing happens! It’s just a bunch of characters walking around a beach doing nothing. What gives? How could anybody find that interesting?

It’s a good question. I agree that White Lotus doesn’t have a ton of plot. But I still think it’s exceptional. Why is that? And how can one write a show or a movie that’s light on plot and still good? I’ll answer that in a second. But first, let’s talk about what plot is because it’s often misunderstood.

Google defines plot as “the main events of a movie devised and presented by the writer as an interrelated sequence.” I’ve heard numerous variations of this definition, probably the most common being, “A series of connected events that happen one after another.”

But I don’t think that captures the full breadth of plot. When you’re talking about plot, there’s a creative component to the variables in the story that needs to be included. When George Lucas comes up with this idea that the Death Star is on its way to destroy the Rebel Base, there’s a lot of creativity that goes into that choice. The idea of a moon-sized base that can blow planets up may be more imagination than plotting. But the base has such an outsized influence on the story, dictating so many plot-threads, that it’s essentially part of the plotting.

I guess what I’m saying is, plot isn’t just the conveyor belt that moves the story along. It’s all the creative elements within the story that affect what’s happening.

I bring this up because, typically, if you’re writing something that’s character-based, it’s a good idea to throw in some creative plot elements to spike the story. Get Out is a good example. It’s a character piece but a lot of crazy things happen during the plot to spike it. Meanwhile, White Lotus doesn’t have many creative plot elements at all, which, I’m guessing, is why the WLHA are so underwhelmed.

They’re probably wondering why I like a show such as White Lotus when I’ve dinged so many screenplays before this for having little to no plot. A recent example is Dust, the script I reviewed last week about a woman stuck in her house during an extended dust storm. I hated that script mainly because NOTHING HAPPENED. So why does White Lotus get a pass and Dust doesn’t? Well, let’s find out.

When you write a character piece, you’re essentially wiping out the “EXTERNAL CONFLICT” portion of the plot (which I talked about yesterday). You’re taking out the killer tsunami. You’re eliminating the bank heist. Nobody’s asking you to jump into multi-verses to capture other versions of yourself. The big external conflict factor is eliminated in favor of internal and interpersonal conflict.

Our plot, then, is the unresolved conflicts *within* the characters as well as *between* the characters. Here’s how the formula works. The writer comes up with a group of characters. For each character, they make them either likable, sympathetic, or interesting. This is what “hooks” the reader. They either like, sympathize, or are intrigued by a character. They’re now invested in that character’s actions and want to see what happens to them.

From there, you figure out the internal conflict. Remember, the internal conflict in a character piece is going to become a plot thread. We don’t have Thanos threatening to kill anyone so the plot needs to come from the character. Mark (the father) learns from his uncle that *his* father, who died a long time ago, didn’t die from cancer like he was originally told, but rather from AIDS. Mark learns that his father was gay and used to sleep with men outside the marriage.

This becomes Mark’s internal struggle. Nothing about his childhood is real anymore. It’s all a lie. Which means Mark’s out of balance. He doesn’t know how to reconcile this new information. So this vacation is him trying to come to terms with this new information and figure out what it means for him as a father and as a husband.

Mark’s journey to find balance within himself is the PLOT of a character piece. As is Rachel’s (the young beautiful wife) journey to figure out if she wants to be a trophy wife for the rest of her life. As is Tanya’s (the older socialite) journey to move on from her mother’s death. As is Quinn’s (the 15 year old social anxiety-ridden son) journey to connect with the world for the first time, which is resolved when he joins the local rowing team.

Now, if you don’t like these characters, you’re not going to care whether they resolve these issues or not. You don’t have the flashy entertainment factor of a James Bond plot to fall back on. It’s just a bunch of unlikable people to you. That’s why you’re bored. But to those of us who like the characters, their journeys to either resolve or fail to resolve these issues is why we watch. We’re fascinated by these people so of course we want to know if they figure themselves out.

The second area where you create plot in a character piece is through unresolved relationships, which we talked about yesterday (interpersonal conflict). If you attempt to plot your movie solely through internal struggle, it’s not going to be enough. Even the most ardent cinephiles need something going on *outside* of the character to be interested. Which is why interpersonal conflicts become so important in a character piece. They’re your main plot engine.

Mike White knew this which is why he spent so much time on the relationships. Will Shane get the Pineapple Suite from Armond? Will Olivia and Paula get their drugs back from Armond? Will Rachel leave Shane? Will Mark and his son connect? Will Mark and Nicole fix their marriage? Will Belinda get the investment to start a new business from Tanya? What will Olivia do about Paula sneaking around behind her back?

To those of us who like these characters, we can’t wait to see how their conflicts are resolved. That’s what’s confusing to those who dislike the show. To them, they’re wondering, “Why do people like this? Nothing’s happening. There’s no plot.” Well, once we became hooked on these characters, their unresolved conflicts were enough of a plot for us. And that’s true for any story, which is why characters are so important. If you can create captivating characters, readers will follow them through weak plots, messy plots, plot-hole filled plots. Which is why I say characters are the most important element of any screenplay.

To summarize, if you create a character we’re interested in, give that character an internal unresolved struggle, then give them between 1-3 interpersonal unresolved conflicts with other characters, that can be enough to plot a story. You’re still on the hook to come up with twists and turns and interesting developments within the story – such as Shane’s mother showing up on the honeymoon – but if you get those three things right (character we like, compelling internal struggle, compelling interpersonal conflicts), you too can write a show as awesome as White Lotus.

And that concludes White Lotus Week. I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did. Monday is Labor Day so I’ll catch you back here on Tuesday!

UFOs, hermaphrodites, lizard monks, and just about anything else your mind can dream up appear in today’s screenplay, written by the co-writer of Raiders of the Lost Ark!

Genre: Adventure

Premise: When a movie exec goes missing in the mountains of Tibet, a British agent named Jimgrim teams up with the exec’s wife to find him.

About: Today’s script, written by the co-writer of Raiders of the Lost Ark, was based on a series of 1920s pulp novels by Talbot Mundy and is said to have inspired the character of Indiana Jones. Some even say Spielberg and Lucas – gasp – STOLE! – the idea. I don’t know if I’d go that far. But they were definitely inspired by the novels.

Writer: Philip Kaufman, based on the novel by Talbot Mundy

Details: written in the 80s, 134 pages

I’ll be honest. I chose this script for one reason and one reason only. The title! I like this title so much that if the script isn’t good, I suggest someone get the rights to the title and write their own version of it. Cause there aren’t too many titles that can imply an interesting story all by themselves.

Now, the timing behind Kaufman’s script is a little strange so let me explain. Indiana Jones came out in 1981. This script was written AFTER that. However, I suspect that after Raiders became a hit, Kaufman decided to use the original source material that inspired the idea to create a separate franchise. No idea if this is correct. If there are google sleuths out there who can clear this up, have at it.

Elmer Rait is a movie exec. Or, he once was. These days he spends his time traveling to remote places all over the world. He spends much of his time in Kathmandu, as he’s searching for a fabled group of people known as the “Nine Unknown.” We watch him trekking at the top of a mountain when he sees… A UFO! And then he passes out and wakes up in a cave with a bunch of monks, one of them a lizard man.

Cut to Erika showing up in Kathmandu. Erika is a movie director and Rait’s ex-wife. Rait used to send her movie ideas during his travels and told her about the nine unknown. She suspects that he may have found them, or died trying.

I guess you can’t just waltz up mountains in Tibet on your own so Erika is forced to hire a guide. And that guide is… you guessed it, Jimgrim! Jimgrim is a British agent and actually friends with Rait. So he should theoretically be helpful. OT: That’s how I think of myself, by the way. That I’m “theoretically helpful.”

After we spend way too much time in Kathmandu, Jimgrim discovers that Rait is in a secret town called Shambhala. Which is going to take them to India! How we went from Rait getting lost in Tibet to India, I have no idea. But, anyway, Jimgrim and Erika recruit seven other trekkers to help them. I don’t know if you do math, but that means there are NINE of them. Nine people searching for the Nine unknowns.

After a very long time (the margins on this script are VERY wide – I wouldn’t be surprised if its true page count is somewhere closer to 200) and a side journey to a town full of hermaphrodites, we find the secret city and Rait. There, Rait explains that he’s infiltrated the “nine unknown” and that their job is to recruit all the knowledge on the planet and use it to rule the world or something. Rait is hoping to take over the group and be the ultimate ruler. Which means Jimgrim and Erika will have to do the unthinkable – stop Rait. Even if it means killing him!

First off, let me say that there is DEFINITELY a movie in here somewhere. This world is exquisitely rich with character and place, moreso than 99% of the adventure scripts I read. I think these pulp novels are in the public domain now. Which means anyone can adapt them. But in order to do that correctly, they need to study how this script got it wrong. TimSlim gets so lost in all of its ideas that it isn’t clear what it wants to be.

Problem 1 occurs after the setup. The setup itself is a little long because there are a lot of characters. But I was intrigued enough to want to keep reading. Then, however, Erika shows up and we just chill out in Kathmandu for 45 freaking pages! That’s half a 90 page script. I mean for crying out loud. Move your story along. This is where the script died for me.

Story momentum is important. Once you lose it, it’s almost impossible to get it back. Especially when the setting and genre imply a movie that moves. This is an adventure movie! Why are we chilling out in rooms for 45 minutes?

The other problem is going to be harder to fix for future adapters. You probably shouldn’t put the name of your main character in the title if your main character is boring as f%$@#. Yes, Jimgrim is boring.

I’m actually excited to analyze this with you today because these novels inspired Indiana Jones, who is considered to be one of the top five movie heroes ever. So we can directly compare the two and, hopefully, learn how to construct a compelling hero in the process. A boring hero is a script killer. This is something you have to get right. So what happened here?

The answer is simple. Indiana Jones is a superhero. He’s a mild-mannered professor during the “day” and a reckless treasure hunter at “night.” We love the duality of the character, not to mention that he’s cool, funny, sarcastic, a rogue, a badass, and lots of other things audiences gravitate to. Meanwhile, Jimgrim is just a guy! He’s a British agent. There’s literally nothing more to him than that. THAT is how you create a boring character, folks.

That’s not to say an agent can’t be interesting. Last time I checked, the James Bond franchise is doing all right. But you have to infuse your hero with some other component if they’re going to be compelling. Bourne figured it out with the amnesia stuff. Which is kind of cliche but it’s better than nothing. The point is, you need to include SOMETHING. I would rank Jimgrim as the 4th or 5th most interesting character in this script. Even Erika is more interesting and she’s just some clueless chick.

Ultimately, this script falls victim to something a lot of big Hollywood adventure scripts fall victim to which is that they think they need to be huge, and in the process of trying to be huge, it becomes impossible to keep the story moving. They’re covering too many people, too many bases.

The beginning of this script had someone killing a man for a map (that Rait used to find the Nine). 80 pages later, that man returns and all I’m thinking to myself is, “Dude, why??” I’m trying to keep track of nine major characters right now. Why are you bringing this guy back? His story is over.

There’s something called SCRIPT MOMENTUM that you must monitor at all times. The more information that needs to be injected into your script, the more you’re impeding on your script’s momentum. Sometimes it’s worth it. Most times it isn’t. If we’re sitting around for too long or sticking with a stagnant plot point for too long, that is often where you’ll lose a reader. Keep things moving. Keep the characters’ eyes on the ball.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: 8 key characters. Assuming you introduce them all in memorable ways – 8 key characters is how many the average reader can remember without keeping notes. I would suggest staying under this number but I realize with some movie ideas, it’s not possible. In those cases, tread carefully. Know that every extra character you include makes it harder for the reader to remember everyone. So make sure those characters are a) necessary and b) extremely extremely memorable. Otherwise, it’s more trouble than it’s worth.

p.s. Notice how I said “if they’re all memorable.” We won’t remember a character introduced this way: JANE, 19, dirty blond, walks into the room.

Genre: Spy/Thriller

Premise: Two CIA operative former lovers meet for dinner and try to figure out what happened five years ago with a complicated hostage plane takeover in Vienna they were involved in.

About: Olen Steinhauer adapted this script from his own novel. The script just sold to Netflix with Chris Pine and Thandie Newton attached to star. Steinhauer has been writing novels since 2003. In 2011, he sold the rights to his “Tourist” novels to Sony.

Writer: Olen Steinhauer

Details: 124 pages

I knew absolutely nothing about this one other than when I saw “knives” in the title I wondered if Netflix was jumping on the Rian Johnson “Knives Out” trend. You know Netflix. They have all that behind-the-scenes algorithmining going on so it wouldn’t surprise me if they greenlit something based on the title’s similarity to another successful title.

More optimistically, I am a Chris Pine enthusiast. I love the guy. I think we would be best friends if we ever met. And check out this curiosity. Who would’ve thought, ten years after the Star Trek reboot, that it would be Pine with the big career and Zachary Quinto struggling?

Not me! I’ve heard some stuff about Quinto having an ego the size of the sun which he uses to club people he works with into submission so maybe that has something to do with it. It’s a reminder for when you hit it big to always be nice to people! Cause unless you’re kicking box office ass, Hollywood has no issue kicking you to the curb.

No idea what to expect from this, which is kinda exciting. Can Netflix totally redeem itself after The Devil Hates Your Pajamas? God, I hope so.

It’s 2009. We’re in a plane parked on a runway in Vienna. A raging lunatic Pakastani terrorist is taking a cell phone video demanding that prisoners from his country be freed. If they don’t, he’s going to kill the people behind him. Pan back to see an entire first class filled with children. The terrorists have brought them up here and told the adults back in coach that for every one of them who tries something funny, a child will be killed.

Cut to the American Embassy in Vienna where we meet Henry Pelham and Celia Harrison. They’re both horrified by the video of the terrorist they’re watching. But before we see the rest of this play out, we cut back a few days ago to see the two in bed together. They’re lovers. What they don’t know yet is that how this terrorist attack ends will split them apart forever.

Well, maybe forever is an exaggeration. More like five years (by the way, this script was written in 2014, so five years puts them in “present day”). Celia has since retired, marrying an older gentleman and spitting out two kids. Henry still works for the CIA and he’s looking to finally close the book on that attack. But first, he wants to ask Celia a couple of questions regarding what happened that have never been answered.

So the two meet at a restaurant near Celia’s home, in Carmel, California. There’s clearly still a spark between the two. But Henry isn’t here for sparks. Or, at least, he doesn’t think he is. There were a number of choices made that day that escalated a manageable situation into a catastrophe.

The main question is it’s suspected someone in that Embassy was feeding the terrorists information. Who might it have been? Where “All The Old Knives” gets interesting is that when each person talks about the past, we cut to the past and see it. However, what we see isn’t always what the two former lovers say to one another.

For example, we’ll see a flashback of Celia being told by one of her bosses that her handler that day, Bill, is selling secrets to the terrorists. But Celia doesn’t tell this to Henry at the table. This initiates a series of dual-but-opposing-clues that leave us wondering who’s telling the truth. Or why one of the parties is withholding the information that they are.

(spoiler) But things get real crusty when we realize these two didn’t come here to get back together. They came here to kill each other. Each of them believes that the other one is responsible for what happened that day. The only question left is which one of them is right. Oh, and will they be able to go on with their life knowing that there’s a chance, however slim, that their belief that the other did it is wrong?

This one did not start well. We begin with the dreaded bulk intro page (that’s when you introduce five or more characters on a single page – it’s literally impossible for a reader to remember who’s who) and followed that up with the triple time jump. 2009, now 2008, now 2014 – all within two pages!

But once I realized what the script was trying to do, I settled in and enjoyed myself.

That’s because Steinhauer makes the clever choice of using the dinner as a framing device around which everything else orbits. This decision grounds the story and makes, what is normally, a hard to follow spy narrative with lots of characters and reveals, a simple “Which one of them is lying?” plot.

All of a sudden jumping back in time worked great because we knew why we were jumping and that we were always coming back to that restaurant.

I love when sophisticated storylines like this one wrap things around a simple construct. Sure, we could run all over the world like a James Bond movie. But this is so much more interesting.

Another thing I loved was that, while it’s one long conversation between two people, the flashbacks keep injecting new information into that conversation. For example, we’ll flash back to Celia talking with her handler, Bill, who warns her about Henry, who is up to something.

Or Henry goes to the bathroom where we reveal that he’s secretly recording this conversation. Then, later still, we learn that Bill was the one communicating with the terrorists. This ensures that what is, basically, a two hour long dialogue scene, never gets tiring. Things are always changing.

It’s like this giant pot of dramatic irony soup. We know something about Henry that Celia doesn’t know. Then we know something about Celia that Henry doesn’t know.

And all of this is wrapped around two additional elements that keep the read really exciting. The first is that these two are clearly still in love with each other. So we have this additional layer of complexity running underneath their terrorist conversation.

Then, on top of that, Steinhauer makes a really good decision not to give away what happened on the plane til the very end. We know something terrible happened. But we don’t know what or how bad it was. So, of course, we want to read til the end to find out.

The only reason this doesn’t rate as an “impressive” is the final reveal. It *does work.*. The script holds together. But for all the secrets and double-crossing we experience, I was hoping for something a little craftier or a little more exciting.

That’s the danger with having any twisty narrative. It’s great to have all these twists in the moment because they keep the reader entertained. But, whether you know it or not, you’re setting up an expectation for an all-time great shocking final twist. And, of course, how many times in history have we had one of those? Ten? Fifteen? In other words, the odds are not in your favor that you’re going to win the twist ending lottery.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s dramatic irony – the act of telling us, the reader, something that our hero does not know. And then there’s dramatic irony with high stakes, which is a whole different ballgame. If we know that Celia cheated on Henry but he doesn’t, that’s fun dramatic irony. But fun dramatic irony doesn’t write memorable scenes. It’s just fun. But if we know that Celia plans to kill Henry and he doesn’t know this, now we have dramatic irony with some real stakes. That tends to lead to great scenes.

What I learned 2: This is, maybe, the best example of how influential information is to a conversation. A conversation where two people are having a straight-forward conversation with each other is boring 99% of the time. It’s the information the reader takes into each conversation that makes said conversation entertaining. You have control of that information so use it. Before Ray talks to Stan, tell us that Stan has owed Ray money for over a year that he still hasn’t paid back. You can then have them talk about anything you want and I guarantee you their conversation will be more interesting than had you not revealed that information to us.

Million dollar spec Tuesday! wooooooo-heeeeee!

Genre: Spy Thriller/Period

Premise: The origin story of MI:6, Britain’s secret intelligence service, that came about out of necessity after the horrors of World War 1.

About: I’d forgotten about this script, which sold for a million bucks back in 2013. I was reminded about it recently when I saw that the writer, Aaron Berg, was in the news for his Atlantis project that sold to Netflix and is teaming him up with Batman director, Matthew Reeves. The reason Section 6 hasn’t been made yet is said to be that the Bond franchise is prickly about the similarities between the project and its own famous spy character. The two were going to go to court over the matter but Bond got cold feet when they realized that, by going to court, they would have to define exactly what makes James Bond “James Bond,” potentially offering a blueprint for other studios to “write around” those tenets and create a bunch of James Bond clones. We’ll see what ultimately happens but with the movement on this other Berg project, expect Section 6 to gain new life.

Writer: Aaron Berg

Details: 122 pages

Scripts like Section 6 aren’t easy reads. They’re sort of like mini-novels with the more extensive world-building, lots of history, and longer descriptive paragraphs. Outside of readers who love the subject matter, these scripts are often met with a groan because the reader knows the read is going to take twice as long.

Why?

Well-written spec scripts have a lot of white space. A lot of dialogue. This means your eyes fly down the page. There’s nothing anyone who reads scripts for a living loves more than their eyes flying down the page.

So what do you do if you’re a writer who likes to write this sort of stuff? How do you overcome this reader bias? Six simple words: Make sure your script is good.

We open on the British Embassy in Russia in 1918. World War 1 has recently ended. It’s a different world we’re told by many a character in Section 6. Ain’t that the truth. A Russian officer charges into the British Embassy being trailed by a bunch of mean Russian soldiers. Those Russians not only kill the officer, they kill all the British workers as well!

Not long after this, a British spy named Thomas Hawthorne heads to the Embassy to retrieve a secret piece of paper that’s been hidden. As soon as he gets it, though, the lights come on and standing there is this meanie named Ivan Vostok. Ivan grabs him to take him back to his torture den to get him to decode the message on the secret coded piece of paper.

Back in Britain, we meet Mansfield Cumming, a former soldier (who now uses a cane) who directs MI-1, the British Foreign Intelligence Service. Cumming is informed by a then spry Winston Churchill that the secret piece of paper Russia now has is a list of Russian politicians to assassinate for Russian revolutionaries (that’s what the opening Russian soldier was running from – he’d just assassinated a high up Russian politician)! If they figure that out, Russia will most assuredly attack Britain.

Cumming’s job is to find someone to infiltrate the Russians and get that piece of paper back before they decode it! There’s only one problem. Britain’s spies at this time were all spineless rich wimps. They were good at hiding and sneakily exchanging information. But they couldn’t do the dirty work. Cumming needs someone who can do the dirty work.

Enter 23 year old Alec Duncan, a soldier who’d been smack dab in the middle of World War 1. If there’s anyone who saw dirty, it was this guy. Currently making his living pickpocketing pedestrians and cheating at poker, Cumming collects Duncan from jail after he’s caught by a local policeman.

You know what happens next. That’s right: training! Cumming helps Duncan ditch his soldier impulses and approach things like a spy would. You have to be sneakier. You have to be faster. You have to be strong under pressure. The only thing Cumming is worried about is whether Duncan, a brute at heart, can hang with high society types. So he sets up a test at a local upper crust function that ends with Duncan crashing two 1918 subway train cars. I’d say that’s a success, wouldn’t you?

After his training, Duncan is sent by boat to Helsinki (this is around page 72) where he meets up with another spy, a beautiful woman named Nightengale, and they sneak down into Russia, find a badly tortured Hawthorne, and get him out. But the Russians don’t give up easily, pursuing them all the way to the sea. Will our tiny team be caught resulting in World War 2? Or will Section 6 be born?

Section 6 is a solid script.

I’m not the biggest spy film fan. But when I do like spy films, it tends to be when they’re doing something differently. I like this angle of a time before spies could be spies. And this was the transition to get them from these polite hoity-toity wusses who got mad if they spilled wine on their shoesies to dudes with a license to kill.

This is always a good thing to keep in mind when it comes to concept creation. You don’t want to just look for subjects. You want to look for subjects in transition. For example, you could make a story about the train industry in the U.S.. Or you could make a story about the train industry during the birth of the American highway system. Because the highway system is going to make the train industry irrelevant, you’ve got a much more conflict-heavy playground to play in.

Disruptive forces are entertaining. Polite spies don’t work in the post World War 1 era where hundreds of thousands of soldiers’ lips have been seared off from exposure to chemical weapons. You need a dirtier spy, someone with a more varied, nastier, skillset.

The reason the script doesn’t get higher marks with me is because of the structure. We don’t send our hero out on his mission until page 72. This creates a second half of the script that feels rushed. For example, we’re meeting this primary character in Nightengale on page 75. Considering how well we know everyone else by this point, she feels paper thin and never quite makes sense for the mission.

Don’t get me wrong. I understand the writer’s dilemma. This is essentially an origin story. With origin stories, you need to lean into the whole learning process. When Spider-Man first gets his powers, you don’t send him after Octopus Guy five minutes later. Spider-Man must first learn how to use his powers, as well as balance out how these newfound abilities affect other parts of his life. That takes time.

I guess it comes down to if you’re an origin-story guy or not. Some people like getting into the nitty gritty of the origin. I just found it hard to reconcile that time was “of the essence” with the Russians getting closer and closer to cracking Hawthorne, and yet we’re taking weeks to train Duncan here. I understand it’s 1918 but still. The whole timing of the separate plotlines didn’t organically mesh.

I did like, however, that by making this a period piece, we got a more interesting McGuffin. These days, the spy film Mcguffins are all the same. They’re some variation of “the nuclear launch codes.” I liked that this was a list of assassinations to be made.

You have to understand, as a reader, we’re experiencing what you experience at the theaters, times 20. So every time you see “nuclear launch codes” in a movie, I’ll read 20 scripts with “nuclear launch codes.” Which means I’m easily turned off by any highly used trope. In contrast, I value writers who change these tropes up. And one of the easiest ways to change tropes is to do it at the concept level. Take us to places we don’t normally go. Naturally, when you do this, you’re going to find things you don’t normally find.

It’ll be interesting to see what happens with this because it’s one of the better scripts I’ve read in the genre in a while. But it does seem to have this giant hurdle to leap in the looming Bond Producer Brigade who are at the bridge, 24/7, shouting, “Though Shall Not Pass.”

And yes, I’m thinking the same thing all of you are thinking. Which is that I should’ve had Scott review this. :)

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Section 6 has one of the more interesting Save The Cat examples. It’s “Befriend the Cripple.” Duncan is friends with a fellow soldier who got half his face blown off in the war and now wears a Phantom of the Opera type mask. It’s a bit cheap. But the love Duncan has for him is very effective in making us like him, especially because he’s a pretty harsh guy that isn’t the easiest to root for.

I have one question for you before I get to today’s article. Is the key to getting an original script turned into a wide release movie one single shot? I know it’s a small sample size but after 1917 made a shocking 36 million this weekend (when was the last time a World War 1 movie made 36 million in a weekend???), we have to ask the question. Cause there was that OTHER original idea – a little movie called Gravity – that was a single-shot film (for the most part) and that became a surprise hit also. Coincidence?

I’m asking the question half-jokingly but it’s an intriguing discussion. It’s so hard to get any original movie released these days. So if you can find any trend out there, you run with it. Now both these movies were writer directors. But I think a spec writer could do an even better job because they wouldn’t be worried about pulling off certain shots and whether something would be too difficult or not. They could write whatever came to mind.

Why does the single shot movie work? Well, obviously, it’s hard to pull off so it’s easy to build buzz around a one-shot movie. But from a screenwriting perspective, if you’re doing something in one shot, you have to create a sense of urgency or else there’ll be a bunch of slow spots in the movie. So, in a way, it forces you to create a really tight exciting story. Might we now get a few single-shot spec scripts in The Last Great Screenwriting Contest? Maybe a single shot social horror thriller even? We’ll see!

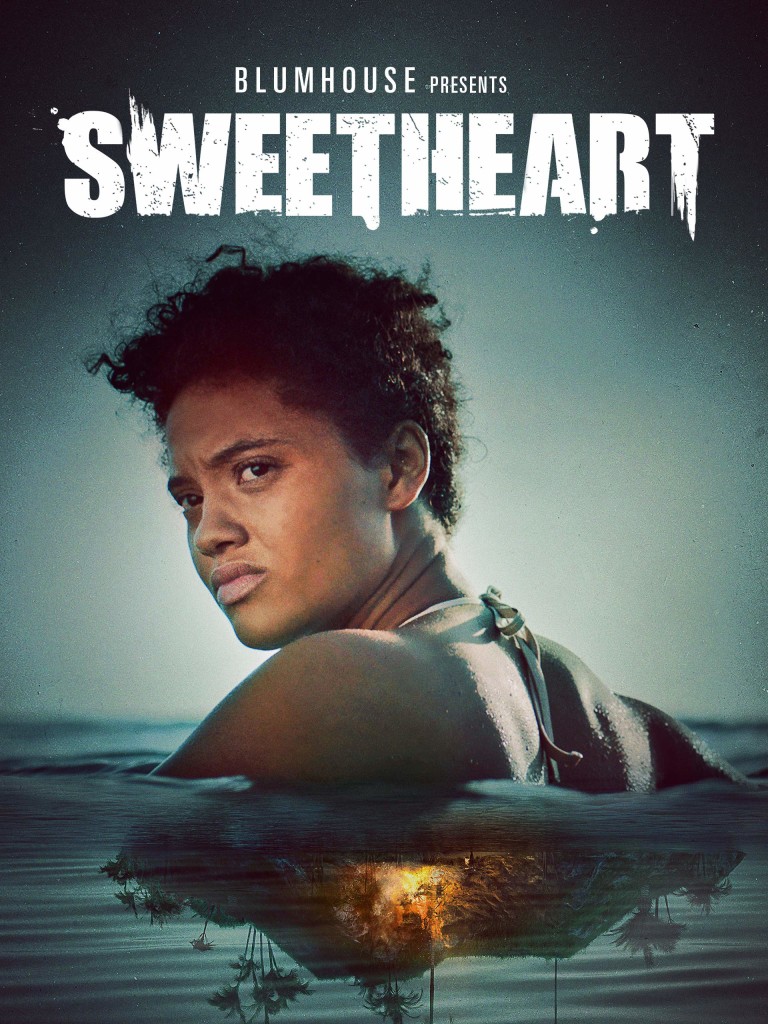

Moving on, I’m going to talk about producing today because that’s where my mind is at. This past week, I stumbled onto a movie called “Sweetheart” on Netflix. The film is about a shipwrecked girl who wakes up on an island only to learn that a monster lives on it as well. The movie follows her journey both trying to survive on an island and trying not to get killed by this monster.

The main reason I watched this movie is because it’s a movie I would’ve made. You’ve got a contained thriller. You’ve got a supernatural threat. That combination has been responsible for a lot of movies that have made a lot of money. You’ve also got a hot young director coming off a hit movie at Sundance. I would’ve seen all these elements and thought, “Slam dunk.”

Unfortunately, as I hit the 30 minute mark of the movie, I was struggling to stay invested. I kept asking myself, “Why? This is a movie you would make. Why isn’t it working!?” As if being able to answer the question would ensure that every future movie I made wouldn’t suffer the same fate. Gradually, after I was able to take my emotion out of it, I realized it came back to script problems. More specifically, it reminded me that contained thrillers are incredibly hard to pull off. And Sweetheart shows you why.

When we come with a contained idea, the first thing we think about is the cool moments. For example, in the big spec contained thriller, “Shut In,” you would think of the moment where the main character nailed the bad guy’s hand into the floor to keep him there. Or, with this movie, you might imagine the first time our heroine sees the monster. These moments are the moments that get us excited to write a script.

Here’s the problem though. There are only about four of five of these big exciting moments in your head when you’re putting an idea together. In the best case scenario, these moments take up fifteen minutes of screen time. In addition to this, you’re likely going to have a big climax, so we can add another 10-15 minutes of screen time on top of that. This means you have 30 minutes figured out. Which means you still have 70 MORE MINUTES TO FILL.

Now filling up 70 minutes in a Star Wars or James Bond movie isn’t that difficult. You just go to a new planet or a new country and throw in a car chase. But 70 minutes in a CONTAINED THRILLER??? Even screenwriting aces have trouble making those minutes interesting. Usually, all you have is a few characters and a small space. What do you do with 70 minutes of that?

That’s clearly where Sweetheart fell apart. It didn’t have a plan for those 70 minutes. It made the fatal mistake of assuming the concept alone was going to do the work for it. That we’d be so excited in the moments between the monster attacks to see it again that we’d wait through anything. Watching a character washed up on an island try to survive on page 10 is interesting. Not so much on page 60, when we’re bored of it.

It’s the writer’s job, then, to come up with plot beats that keep the story moving. And, to their credit, they try. For example, a couple of other shipwrecked characters (from her ship) show up about 50 minutes in. And that, at least, gives us some new scenarios, like characters being able to have a conversation. However, the plot beats were lazy. In fact, there’s another girl washed up on a deserted island with a monster spec that was written at the same time as Sweetheart. What happens at the 50 page mark of that script? A couple of shipwrecked characters show up. In other words, your story choice was so predictable that the only other person writing this idea came up with the same plot beat.

It is IMPERATIVE as a screenwriter to always check yourself on these things. When you come up with a plot development, one of the first things you should ask yourself is, “Would someone else come up with this as well?” And if the answer is yes, don’t write it. Come up with something else. The counter-argument to this is, “Well how many plot options are there in this scenario? Bringing in new characters is one of the only things you can do.” There’s never a situation where there’s only one thing to do. There are always options. It’s definitely harder to come up with the options that nobody’s thought of yet. But those are the ones that are going to make your script great.

Another issue was that there was no sense of danger in a script about a woman stuck on an island with a monster. She and the monster routinely see each other and nothing happens. She’s easily able to hide under a log or behind a tree. It gets to the point where you’re wondering if the monster is even interested in killing her. If the only person in your thriller script isn’t in danger, you don’t have a thriller.

In retrospect, I think I know why they did this. If the monster is too aggressive and powerful, the movie’s over in five minutes. The only way to make the movie last was to make him passive. But then where’s the movie? The last time I checked, the alien in “Alien” doesn’t occasionally walk by the characters, uninterested in them. It aggressively hunts them down one by one. And I’m not bashing Sweetheart for not living up to the greatest sci-fi horror film ever. I get that these are tough script problems to figure out. But if the audience isn’t feeling fear for your hero, we don’t have anything to work with.

I bring this up in the hopes that those of you writing contained thrillers for The Last Great Screenwriting Contest approach these dangerous 70 minutes strategically. You might want to watch Sweetheart and read Shut In back-to-back. In Shut In, we have two children in danger outside the room our hero is stuck in the entire movie. That alone adds a sense of urgency and tension that Sweetheart never had. It ensured that we were always rooting for our hero to escape the room so she could rescue her kids.

And that’s probably the best lesson to learn for a contained thriller – personal character-driven stories give you the best chance at surviving those big gaps of screen time where you don’t have a set-piece. I’m still on the edge of my seat for the Shut In heroine when all the noise died down because I still want her to save her kids. I’m not scared for the Sweetheart heroine at all because, from what I can tell, this monster isn’t interested in killing her.

Did you guys see Sweetheart? If so, what did you think?