Search Results for: scriptshadow 250

IMPORTANT NOTE: THE SCRIPTSHADOW 250 CONTEST DEADLINE IS NOW 3 ½ MONTHS AWAY!

On a lark I decided to catch the Bates Motel TV show recently. I mean how bad could it be? It had Carlton Cuse as the showrunner, who did Lost. And the cast looked strong.

I’ve been pleasantly surprised so far. I mean, you have to come to terms with the fact that the show takes place in the present (Was Norman Bates cloned?) but once you do, it’s entertaining television.

I bring this up because I’ve been watching a lot of television lately – trying to crack the TV code – and I’ve come to the realization that writing for television REALLY HELPS when it comes to writing character.

That’s because you’re forced to know a lot more about your characters in TV than what’s happening in the here and now. You’re thinking three episodes down the road. Six episodes. Even twelve.

As someone who reads a lot of features – features that leave me feeling zero emotional attachment to the characters – this is a revelation. Taking a long-form approach to character forces you to know your characters in a way you never would on the feature front.

Which brings us back to Bates Motel. There’s a moment early on in the second season where Norma Bates’s brother comes to town. And it turns out he and Norma share a dark secret. Normally, this is something a feature writer wouldn’t know, especially if the brother never appeared in the movie. But here, the writers had to know because his entrance into the story needed to be built up.

So as an exercise, I’d like you to approach your feature characters with a TV mindset. Get to know them beyond the 110 minutes that take place in your story. This simple change is going to add a depth and dimension to your characters that you never knew was possible.

To get a little more specific, we’re going to call this the 3-D Method. Those three “Ds” represent the PAST, the PRESENT, and the FUTURE of your character. I guess in a way you can look at me as the ghost of screenwriting. But the budget’s cheap so I’m going to have to play all three parts. Let’s get started.

1-D) PAST

The “PAST” component of character creation is almost exclusively reserved for backstory. It means figuring out as much about your character’s life, up until when your movie begins, as you can. We can actually break this down into two sub-sections. “Relevant to Plot” and “Non-relevant to Plot.” When you’re figuring out backstory that’s non-relevant to your plot, it’s more for you than the audience. A lot of this stuff will never make it into the script, but it will inform your choices about the character. For instance, if your character was raped when she was 15 by a close family friend, she’s probably going to have a problem trusting men. Therefore, you can add a little distance to the character’s personality when she’s around men she doesn’t know. She’s the kind of girl who hangs back and needs to get to know the person before she opens up.

“Relevant to plot” backstory is much different. This is backstory that will directly play into the plot at some point in your movie. So say your main character had an old girlfriend he was never able to get over. Now he’s happily in a new relationship. Near the midpoint of your movie, then, that ex pops back up and has your character second-guessing his current relationship. Obviously, relevant backstory should take precedence. But backstory that isn’t directly related to plot is still mucho importento. The writers who stand out are the ones who add specificity to their writing. And you achieve this by knowing as much about your character’s past as possible. I mean Batman is just a guy in a mask if he never had that experience with the bats. The more you know about your character’s past, the more real they’re going to appear on the page.

2-D) PRESENT

The present is really about your character’s IMMEDIATE MINDSET. What’s going on in that head of his within the two-hour lifetime that is your movie? There are a few things you want to explore here. First, know what your character wants RIGHT NOW, as in IN THIS STORY. They might want a promotion. They might want an engagement ring from their boyfriend. They might want to kill the bad guy. Know what’s driving them. Next, know what mental block is holding them back from achieving that. Maybe they doubt they’re strong enough to make a difference (The Matrix). Maybe they put work/country over family (American Sniper/Interstellar). Maybe they’re afraid of becoming old and boring (Neighbors). Get in your character’s headspace and understand what their issue is RIGHT NOW.

Finally, understand the key issues in your character’s current relationships. Maybe one character believes we need to seize the day while another believes we need to focus on the future (Jack and Rose in Titanic or Ferris and Cameron in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off). Maybe your character struggles with opening up to others (Skeleton Twins). You can’t explore characters in any meaningful way unless you have unresolved issues in those characters’ relationships. There will be some crossover between the past and the present depending on if the characters knew each other before the movie started. So with Skeleton Twins, about a brother and a sister, they’ve known each other their whole lives so this is as much a past issue as it is a present one. With Titanic, the issue is purely in the present since the characters meet for the first time on the boat.

3-D) FUTURE

This is where the TV approach really kicks in. In TV, you need to have a plan for the show’s future. You can’t just make shit up on the fly or the show will fall apart (see “Prison Break” or “Heroes”). For example, you might know that a friend of the main character dies a year down the line. This knowledge allows you to build stuff into the present storyline that will make that future storyline stronger. So you might build a deeper friendship between the two characters so that when the character DOES die, it’ll hit the audience harder. Now, obviously, with features, knowing if a character dies a year down the road isn’t as relevant since it won’t affect the current movie. But there are aspects of the future you do want to think about. For example, where do you see your character five years from now? Are they happy? Successful? Or are they unfocused, self-destructive, no better off than they are today? Probably the most important question you want to ask is, what’s your character’s goal in life? Where do they want end up? Do they want a family? Do they want to still be partying at the nightclubs 7 days a week? Or maybe they want to follow their dream of writing a novel. Answering that question will give you loads of insight into who your character is. You can really get into the psychology of a person by knowing what they want out of life.

Once you know someone’s past, present, and future, you essentially know their entire life. One of the easiest ways for me to spot a newbie is that their knowledge of their characters is limited to the amount of time their story takes place. They don’t know where their characters have been and they definitely don’t know where their characters are going. The 3-D Approach insures that you know every aspect of your character – present, past, and future. And while I can’t promise you that using 3-D will help you create superb characters every time out, I can promise you that it’ll make your characters way better than if you did nothing at all. So let’s write some kick-ass characters this weekend. And feel free to share some character-creating secrets of your own in the comments section. :)

Note: FOUR MONTHS LEFT UNTIL THE SCRIPTSHADOW 250 DEADLINE!!!

So over the past few weeks, I’ve had some discussions with writers gearing up to write their next screenplay. Some of these were new writers with only a few screenplays under their belt. Others have been trying to break in for 10+ years. The discussions universally gravitated towards, what’s wrong? Why haven’t my screenplays sold or gotten me an agent, or even gotten my best friend to read them?

95% of the time it comes down to that the concept isn’t any good. And the fascinating thing I’ve found over time is that the writer actually knows this. They’ll actually say to me, “I know that the concept isn’t very good but this isn’t about the concept. This is about the characters and their journey they go through and blah blah blah…”

Hold up, hold up, wait a minute, hold on.

What did you just say?

Did you really just say you knew the concept wasn’t any good? And you still wrote the script?? Believe it or not, this answer is so pervasive in the amateur writing ranks, that I don’t know why it still surprises me. The only explanation I can come up with for why they do it is that they believe they’re different in some way. That they’re special. And the rules don’t apply to them.

Unfortunately, that’s not how this business works. This business IS a concept-driven business. Not only because the script has no chance of getting made unless the concept is good. But because Hollywood is a numbers game. Everyone says no to everything – EVEN GOOD CONCEPTS. A yes only comes along every once in awhile. Therefore, you have to spread the widest net and get the most reads in order to get that yes. If you have a lame (or boring, or uninspired) concept, you’re not going to get the number of reads necessary for the odds to pay off. A good concept gets 50, 100, 200 times the number of reads a boring concept does. Imagine how much better your chances are of breaking in with those kinds of odds.

So how can we ensure we have a good concept? Aren’t those hard to come up with? I mean, if it were easy, everyone would be doing it, right? Well, before we get to how to write a good concept, let’s start with how to avoid writing a bad one.

A new phrase I want you to add to your screenwriting vocabulary is: “The Potential of Boring.” If your idea sounds like it has the potential to be boring, don’t write it. This is not to be confused with the script itself. The script (or the movie) may in fact be the greatest movie ever. But if it SOUNDS like it has the potential to be boring, don’t write it. Because, chances are, nobody’s going to read it. One of my favorite movies of the last two years is Philomena. I loved it. I would never, in a million years, however, allow an amateur writer to write that spec. Why? Because it’s about an old woman who goes searching for her son. The average person hears that and they think, “That has a strong potential to be boring.” Ideas that sound like they have the potential to be boring will not get read.

Another good way to know if you’ve got a boring concept is to play the elevator game. Pretend you’re stuck in an elevator with a Hollywood producer and he asks you to pitch your movie. Go, do it right now. Pitch your movie to Imaginary Producer in Elevator Guy. It should become clear very quickly whether you have a good concept on your hands. If you’re sitting there going, “… and she goes on this road trip of self-discovery and meets this guy. And he’s a drug-addict and then she remembers that what really brought her happiness was her poetry so she starts writing poetry, going from town to town, performing on the street…” That script’s not going to get read. “A young family excited to start their life together finds the perfect home, only for the college’s biggest fraternity to move in next door.” That’s going to get you a read.

As far as how to come up with a good concept, there isn’t any one way. There are clever ideas (like Neighbors, which I just noted), there are ironic ideas (like The King’s Speech, about a man who can’t speak who must give the most important speech in history), but if you’re still stuck trying to find that big idea, start by thinking “LARGER THAN LIFE.” Focus on a scenario that’s bigger than what happens in your everyday life. Going to pick up groceries then coming home to have a fight with your wife isn’t a movie idea. Going to pick up groceries, coming home to find your wife spread out on the floor dead, and the cops think you did it so you have to go on the run. That’s a movie idea. But I’m going to take this one step further. The larger than life your idea is, the more likely it is that it’s a movie idea. The Hunger Games, Guardians of the Galaxy, Captain America, The Hobbit, Transformers, Maleficent, X-Men, Big Hero 6. These ideas take place in different worlds, different universes in some cases. They’re larger than everything.

Let’s see how this can be applied to a basic idea. Say you want to write a movie about sex. So you write about normal people obsessed with sex. The movie is called Nymphomaniac. It makes 10 dollars at the box office. Why? Because there’s no “larger than life” angle to it. In comes Fifty Shades of Grey, currently the highest grossing movie of the year. Let’s now make one of the characters a billionaire. How many billionaires do you know in your everyday life? I’m guessing none. This aspect gives it a “larger than life” feel.

That might not be the best example, you can always skew the numbers in your favor when making these arguments, and there will always be exceptions to the rule. But I’m telling you. By and far, over the last 30 years of this business, this is the formula that wins out for writers trying to break into the industry.

Now there’s one writer I was talking to in particular who had been writing for about seven years. He was a good writer too, and he was frustrated that he still hadn’t broken in. I pointed out to him that none of his scripts really satisfied the “larger than life” criteria. There were a few you could argue were close. But like I said, the MORE larger than life it is, the better your chances are. And he tended to keep his stories more grounded, more based in reality. Which is exactly what he said to me. “But Carson, what if I just don’t like to write those kinds of movies?”

And I realized that some people just want to write about real human conflict, real human drama, without all the hoopla of a flashy concept. They’re more interested in reality. To these people I would start off by saying, “Understand that by taking that stance, you’re making your chances of success infinitely harder.” Once you’ve accepted that, we can go to the next piece of advice. And the next piece of advice would be this: “Stop bullshitting yourself.” It is completely possible to write a human drama wrapped inside a big concept. I’ll give you an example.

A couple of years ago, a writer broke through with one of the hottest scripts in town. It was called “Maggie,” and it was about a young girl who was turning into a zombie. Except in this take on the mythology, it took six months to turn into a zombie. I thought the script was okay, but that’s not the point. The writer was a genius. He wanted to write a story about cancer. But if he wrote a story about cancer, he knew no one would read it (keep in mind, this was before Fault in our Stars). So he placed the allegory inside of a marketable genre that made the story more high-concept. He told it as a zombie tale. And just like that, the concept is larger than life.

You can explore the human condition inside of ANY idea. So don’t fool yourself into thinking you have to write about a small town family who struggles to make ends meet after the dad loses his job in order to explore people. There was a script on the Black List a couple of years ago that did a wonderful job exploring a family amidst an alien invasion. Guess which one of those scripts is getting read? And they’re both doing the same thing – exploring the human condition. It’s just that one writer was smarter – he gave his story a wrapper that would make people interested. Hopefully, you can learn from him.

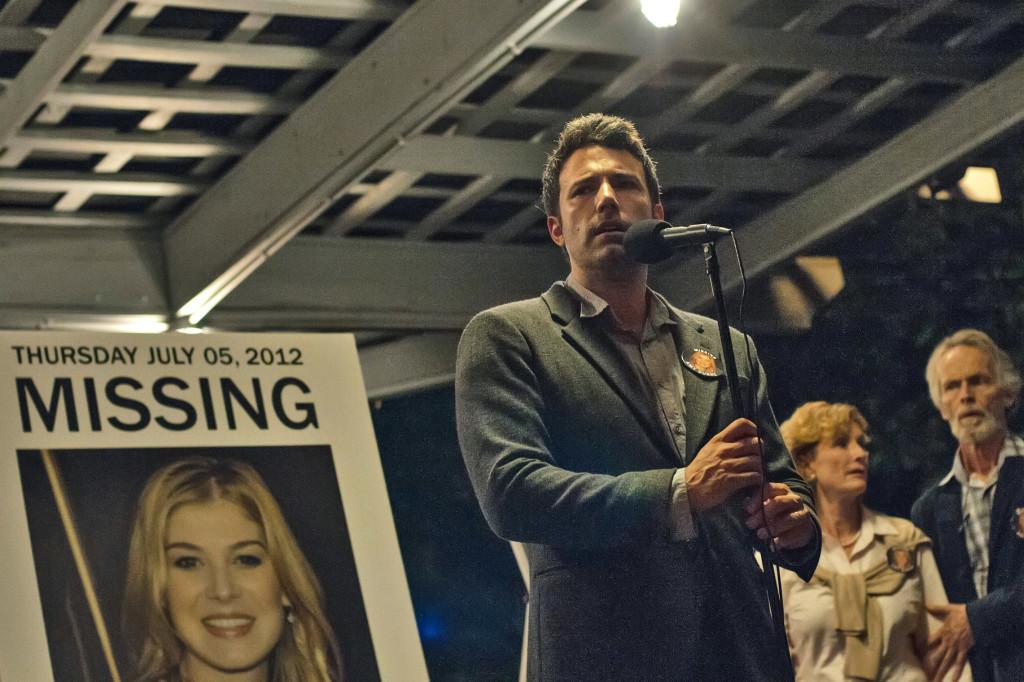

Gone Girl had a really exciting second act.

Gone Girl had a really exciting second act.

So the other day, a writer told me he’d been excited about entering the Scriptshadow 250, but lately, he didn’t know if he’d be able to finish his script on time. “You’ve got over three months,” I told him. “What don’t you have time to do?” “I just can’t seem to figure out second acts,” he confided. “I can make it through about 15 pages, but then I have no idea what to do next.”

Getting lost in the second act is not a new problem for screenwriters. In fact, on the list of screenwriting fears, it’s usually up there with writer’s block. But just like any problem in screenwriting, the solution presents itself once you break down the issue. And what I’ve found is that the writers who have problems with second acts are the same writers who never learned how to tell a story properly in the first place. So let’s start there.

Most stories are told by introducing a problem into a person’s life. That problem becomes the impetus for that person to ACT. This is obvious when you think about it. If you encounter a problem, you only have two options. Do something or do nothing. Most people will do something. That something becomes their GOAL. And the unresolved nature of that goal (will he or won’t he achieve it?) pulls the reader along until, at the end of the story, our person either succeeds or fails. So, to summarize:

THE GOAL IS ALWAYS TO SOLVE THE PROBLEM.

Look at almost any movie and this sentence holds true. (Problem) Hitler is looking for the most powerful religious artifact in history and plans to use it to take over the world. (Goal) Therefore, Indiana Jones must find that artifact first. (Problem) A giant monster has emerged from the bottom of the ocean and threatens to destroy the world. (Goal) The military must stop it. (Problem) In the popular film, Gone Girl, a wife has disappeared and the husband is suspected of her murder. (Goal) The husband must find out what happened to his wife.

Once you understand this basic principle, you have all the tools you need to tackle your second act. Because while a story starts out as a problem a character must solve, it becomes, in its second act, a series of conflicts that put our main character’s success in doubt. Let’s see if we can summarize that:

THE SECOND ACT IS WHERE YOUR MAIN CHARACTER ENCOUNTERS CONFLICT

This is a very simplistic assessment of the second act, but as you’ll see, it holds true in just about every movie you’ve ever seen. During those middle 60 minutes, nothing seems to be going right for the hero. He always appears to be running into trouble. This “plot conflict” is the first of two planes you need to master in the second act.

As we’ve already discussed, your character’s goal is to solve a problem. The second act, then, must make solving that problem the most difficult thing your character has ever had to do. You achieve this by placing OBSTACLES in front of the character’s goal.

For example, in Gone Girl, Nick needs to find out where Amy is so he doesn’t get sent to prison for the rest of his life. That’s his goal. The second act, then, is a series of obstacles thrown at Nick to make his job difficult. One of those obstacles is that his affair with another woman is exposed. If Nick is having an affair, it’s all the more reason for him to get rid of his wife. Later, another obstacle is introduced in the form of Amy’s journal. In the journal, Amy talks about how Nick is “dangerous,” how she’s scared of him, and how she thinks he might harm her. Yet another obstacle that makes his goal more difficult.

True, not any old obstacles will work. You need to be imaginative. And the obstacles themselves must hold weight. But if you continue to come up with good ones, it’s not hard to keep the reader’s interest.

But plot obstacles are only half of the second act battle. You also need to explore your hero’s relationships. When screenwriters give up on screenwriting, it’s usually right before they figure this part out. Because before you figure this tool out, your second acts are just plot. They’re robotic efficient story movers. But they lack emotion, lack soul, lack heart. In order to bring that feeling into the story, you need to master the art of inter-character conflict.

Inter-character conflict works like this. For every relationship between your main character and someone else, you need a SPECIFIC UNRESOLVED CONFLICT between them. Don’t be vague about this. Write it down somewhere. I’m going to make this very clear. Understanding the specific issue/problem/conflict in each of the key relationships in your screenplay allows you to explore your characters on an EMOTIONAL LEVEL so that your story isn’t just a robotic plot mover, but rather a living breathing exploration of the human condition. And that’s what makes a second act work. Here are a few unresolved conflicts between characters from well-known movies.

Silver Linings Playbook

Pat and Tiffany – She loves him, but he’s still in love with his ex-wife.

Frozen

Anna and Elsa – Elsa avoids a loving relationship with her sister in fear that she will hurt her.

Gone Girl

Nick and Detective Rhonda Boney – Despite wanting to believe him, she suspects that Nick killed his wife.

Neighbors

Mac and Teddy – Mac just wants to raise a family. Teddy just wants to have fun.

The Social Network

Mark and Eduardo – Mark is more interested in their company. Eduardo is more interested in their friendship.

Now I’m highlighting the main relationship in all of these movies, but your hero should have 2-5 key relationships in the script, and you should have a conflict for each of them. Once you have that conflict written down, every scene between those characters will, in some way, explore that issue. This is why we, as an audience, watch. We want to see if these characters are ever going to resolve their conflict!

When writers don’t inject problems/issues/conflicts into their relationships, the scenes between the characters are often lifeless. And why wouldn’t they be? If you don’t have anything to hash out, anything making your relationship difficult, it’s nearly impossible to draw drama out of the relationship.

Take a look at yesterday’s script, Huntsville. The key relationship in that story was 40 year old Hank and his friendship with 17 year old Josie. So I ask you – what’s the problem (or conflict) in this relationship? It’s pretty obvious, isn’t it? Hank wants Josie but can’t have her. It’s illegal. Therefore, every scene they’re in together is laced with that unresolved conflict. Will Hank make a move? Will the relationship go to the next level? The idea is to create a circumstance where the reader asks the question: “How is this going to be resolved?” If that question doesn’t come up, you’re not doing your job.

Take another recent script review: The Founder. What was the main problem between Ray Kroc and Mac McDonald? Ray wanted to expand the business. Mac was fine with the way the business was. Every phone call between the two in that second act revolved around this unresolved issue. These contentious discussions upped the conflict, which upped the entertainment value. The Founder doesn’t work if there isn’t any problem between Ray Kroc and Mac McDonald.

When seeking out conflicts to explore in relationships, two great places to look are your own life and (yup, I’m being totally serious here) reality TV. One of my friends has a testy relationship with her mom because her mom thinks she needs to get married now when she’s still young and pretty. My friend, however, isn’t in any rush. There isn’t a phone call that goes by between the two where this isn’t discussed outright, passive aggressively, or through subtext. Someone else I know disavowed his best friend because that friend is now dating his ex-girlfriend. You should see what happens when those two are in the same room. I once knew a guy who was in a three-year relationship with a woman he loved dearly, but that woman was an alcoholic and refused to quit drinking. Every day for him was a struggle.

Reality TV does this in a more on-the-nose way, but they’re still good at it. Most reality shows these days depend more on character than plot, so they put a ton of emphasis on relationship conflict, which is the same thing I’m asking you to do. It’s why you always find the religious nut and the gay marriage advocate on the same show. Or why two exes who never quite got over one another are brought back together. Or why a father is featured on the show of a man who’s never been able to achieve his dad’s approval. I’d argue that almost every reality TV show these days is about relationship resolution. So don’t be ashamed to study them.

That’s pretty much the basics for how to handle your second act. Plot obstacles and relationship conflict. And actually, when you think about it, it’s all conflict. Obstacles create conflict for the plot. Unresolved issues create conflict between characters. Are there other things to focus on in the second act? Of course (your main character battling his flaw for one). But if you master these two things, you should be able to write some kick-ass second acts. Which you’ll need to if you’re going to win the Scriptshadow 250! ☺

It’s a busy day here at Scriptshadow. I’ve been checking out the Scriptshadow 250 entries as well as finishing up some consultations, so I don’t know how long this article is going to be. What I can say is that I’ve already started to spot some common mistakes in the entries and I want to make sure they don’t keep happening. So today, I’m giving you three tips that should help improve your Scriptshadow 250 entry as well as make you a better overall writer. As always, I offer this reminder. Be mindful. With great power comes great responsibility.

ALWAYS FIND FRESH TAKES ON OLD TROPES

There are certain tropes in screenwriting that are unavoidable. They seem to go hand-in-hand with the genre they’re written in and there isn’t anything wrong with that. What is wrong, however, is giving the reader the same old version of the trope. It’s your job to find a fresh take on it, something that makes it feel new and exciting, and not business as usual. Take the well-worn cliché of a down-on-his luck gambler whose bookie sends his thugs in to demand a payment. This scene often takes place at a bar, or maybe just outside of the character’s apartment as he’s leaving. The bookie slams him up against a wall and says, “You’ve got 1 one week to find the 50 grand. Or else you’re dead.” Sound familiar? Yeah, if you knew how many times I had to read this scene, you’d never write it again.

The thing about the “fresh take” approach is that it requires NO EXTRA SKILL on your part. You don’t have to be more talented or more experienced. The only thing it requires is time and effort. For that reason, there should be no excuse. I read a script once where our main character was at a school function, watching his child run around and play with the other kids, and the bookie arrived, dressed just like any other parent (his tattoos still peeking out of his shirt though). He very quietly and calmly stood next to our main character, and, while watching the children, proceeded to tell him that he was going to kill him in 5 days if he didn’t come up with the money. The irony of a bookie demanding money juxtaposed against the innocence of kids playing was exactly the fresh take the doctor ordered. If there’s any trope you come across – any plot beat that you’ve seen in a lot of films – it’s your screenwriting DUTY to do something fresh with it.

WRITE YOURSELF INTO CORNERS

I’ve been reading a lot of scenes, lately, where the writer writes his hero into a “tough” situation that isn’t tough at all. Therefore, when the character makes his incredible “escape,” it’s as exciting as watching reruns of Two and a Half Men. What’s happening here is that the writer’s scared to make things too difficult for their hero, lest they not be able to figure out a way to get him out of trouble. What the writer doesn’t realize is that the reader always feels this. They know you’re playing it safe. Which is why the character’s escape lacks suspense.

From this point forward, be bold. When your character is facing a bad situation, make it as bad as it can possibly be, even if, at first, you don’t how you’re going to get them out of it. It’ll be scary, but that’s exactly what you want. If you’re unsure, the reader will be unsure. Then, like a detective, write down a list of the ways the character might get out of the situation. It won’t be easy, and it shouldn’t be. If the solution comes to you right away, the situation wasn’t dangerous enough. But eventually you’ll figure it out. Recently I read a script where the co-pilot of a small plane planned to kill his captain. The co-pilot sabotaged the plane, grabbed a parachute, and jumped out. The captain, while admittedly having to hurry up before the plane plunged into a field, merely had to find the other parachute and jump to safety. I told the writer to have the co-pilot tie the captain up before jumping. And I told him to have there only be one parachute, the one the co-pilot took. Do I have any idea how the pilot’s going to get out of that situation? No. Which is exactly why I’m a lot more interested in what happens next.

FLIP THE SCRIPT IN A SCENE

You may have heard me mention that I’ve been watching House of Cards recently. Watching the episodes one after another has allowed me to catch a few of their tricks. One of the moves I notice a lot is the “flip-the-script” scene. This is where it looks like one character is in control of a scene, only for a “twist” to occur at the scene’s midpoint that results in us realizing the other character was in control the whole time.

For example, there’s a (non-spoiler) scene where a reporter from the Washington Post is at a bar, and this beautiful woman starts flirting with him. For the first half of the scene, she’s completely in control, manipulating our helpless reporter with her looks and sexuality. Then, just as it’s looking like he’ll succumb, he casually pulls out a picture of a girl he’s been looking for and places it in front of the woman. He asks her if she’s seen her. It turns out our bar woman was an escort who walked in the same circles as the girl our reporter was looking for. All along, he was playing her. The simple truth is that if every scene goes according to plan, you might as well put a “nap” tag on your script. “Flip-the-script” scenes send a jolt into the scene, and by association, the story, letting the reader know that not everything will go according to plan.

Driver waiting for his opening scene!

Driver waiting for his opening scene!

I cannot WAIT to read your Scriptshadow 250 submission. But if you’re going to have any shot at winning this thing, you’re going to need to bring it. I don’t think that’s a surprise. To help you, I went back down memory lane to try and identify the simplest way to tab a script good or bad. It didn’t take long to find my answer. In about 95% of the screenplays I read, I can tell if the writer has the goods in the VERY FIRST SCENE. And I’m guessing it’s the same for most readers.

You see, the opening scene is the reader’s introduction to both YOU and YOUR SCREENPLAY. Much like a real-life introduction, the other person is sizing every detail of you up to decide whether they like you or not. Are you dressed well? Do you have good hygiene? Do you have good posture? Do you look them in the eye? Are you arrogant or humble? Do you speak clearly or mumble? Do you smile or have resting bitch face? All these clues help this person determine whether you’re someone they want to get to know better.

The exact same thing is happening during your opening scene. That’s because you’re giving off tons of hints about if you know what you’re doing or not. The first thing I typically look for in a scene is: Is anything HAPPENING? Then, is the writing crisp and to the point? And finally, is it clear what’s going on? If the writer’s passed this test, congratulations. He’s done exactly what’s expected of him. But all this gets him is an extended evaluation period.

Guess what? I don’t want you to write “extended evaluation period” first scenes. I want you to write GREAT first scenes that IMMEDIATELY GRAB THE READER and announce that you’re a writer who knows how to entertain. A lot of writers never get past this point. They don’t realize there’s a difference between showing that you know what you’re doing, and actually PULLING A READER INTO A STORY. You need to master the latter.

So what do you do to pull the reader in with your opening scene? YOU TELL A STORY WITH THE SCENE. Repeat that back to me.

What does that mean? It means using storytelling devices that make the reader want to continue reading. Most writers do the opposite of this. They think they’ve earned some divine right which states that you, the reader, must afford them your full concentration for the entire script no matter how boring it is because of how much work they’ve put into the script. They can take their time, dammit. Because wait til you get to that whopper of an ending!

No. Nada. A reader OWES YOU NOTHING. It’s you who owes them. You owe them entertainment from the very first page and if you don’t give it to them, they have every right to check out, even if it’s on page 3.

What are these mythical storytelling devices I’m referring to? They include but are not limited to: Conflict, tension, suspense, dramatic irony, a sense of foreboding, mystery, surprise, a difficult choice, a twist, dropping us into the middle of some action, and so on. Do one or a combination of these things in your opening scene and, as long as the scene is somewhat original (or at least a fresh spin on a common scene) you should pull the reader in.

Let’s look at two examples – the wrong way and the right way. The scene we’ll use is one I’ve read a million times before. It’s the scene where the main character, often a 30-something man-child, wakes up in his bedroom, which we notice is a complete shit-hole, with dirty clothes and empty beer bottles piled everywhere. The extent of the writer adding a “story component” often entails the hero checking his clock, realizing he’s late for work, and running out of the room.

That’s what I call a terrible opening scene. Nothing is happening. There’s no story to the scene. It’s unoriginal. It announces to the reader that you are putting the least amount of effort into your opening as possible. And that conveys to the reader that you will continue to do so throughout the screenplay. I mean if you couldn’t even get excited enough to write a fun original FIRST SCENE??? Of course you’re not going to try for the other 59 scenes.

Let’s look at the second example. This is a scene that was in a screenplay I read a long time ago, but I’m forgetting the title. In it, we have the same 30-something man-child character waking up, hung over. But this character wakes up in a child’s bedroom. He’s actually in a little girl’s bed, naked under the covers. The shelves are packed with dolls. Next to him is a crib. We can tell he has no memory of how he ended up here. The scene then follows how he figures out where he is and how he gets out of the house.

The big difference in this second example is that the writer has added MYSTERY to the scene. He’s shown the ability to think forward – to dangle a question in front of the reader so that he’ll want to keep reading – namely “How did this character get here?” This is an oversimplification of the difference between a good and bad opening scene, but the point is, the second example tells a story while the first version is just character set up – and boring character set up at that.

Let’s look at another example. Say you’re writing a cop drama (or even a cop comedy). I want you to imagine who your main character might be, and then try to come up with an opening scene for him. It’s not easy. You literally have an unlimited number of choices. The funny thing is, the beginner writer will always take the path of least resistance. So they’ll often go with whatever comes to mind. Maybe the cop shows up at a murder scene where he’s briefed by the Captain on what they know about the victim.

Hmm. Haven’t seen that scene before, have we?

So ask yourself – how can I turn this same scene into a story? Well, instead of your cop showing up last, after everyone else has already done the work, what if he shows up first? Then, as he’s observing the crime scene, he encounters a clue that implies the killer is still on the premises. Now we have danger, suspense, mystery. You can even add some dramatic irony if we cut to the hiding killer, who isn’t yet aware that our hero is onto him.

Yeah yeah, we’ve seen this scene before, too. But it’s still a much more entertaining scene than the first one, and way more likely to pull a reader in.

Now all of this sounds great in a vacuum. But over time, I’ve come to learn that every script is unique. Each story has its own requirements, and those requirements sometimes work against you doing the things you want to do. One of the hardest things to balance is setting up your main character AND writing an entertaining opening scene at the same time.

Take The Equalizer. In that screenplay, Richard Wenk needs to establish that Robert McCall lives a very simple reserved lifestyle. As you can imagine, there aren’t many exciting ways to convey “simple” and “reserved.” So the opening scene is McCall tidying up his sparse spotless apartment. It sets up the character perfectly, but makes for a weak opening scene.

Contrast this with Drive, in which Driver (Ryan Gosling) is an ice-cold brave-as-shit getaway driver. That more naturally lends itself to a strong opening scene – which is exactly what we get. Driver expertly evades a group of cops while driving his two accomplices to safety.

So yeah, we have to work with what we have. But I want to go back to that Equalizer scene for a second. It is a boring opening scene. But Wenk clearly knows that. So he uses sparse description and only highlights a few brief things in order to get McCall out of the apartment and into the world as quickly as possible. As a reader, I may not be wowed, but the writing is so minimal and the actions so clear that I’m willing to reserve judgment until after a few more scenes. Had the writer kept McCall in his apartment for three more pages and described a bunch of needless things, I would’ve known immediately that the script was doomed.

So does that mean sometimes we HAVE to open with a boring scene and just do the best we can? This is the way I look at it. You’re a spec writer. You’re not writing on assignment (like Wenk on The Equalizer). You’re not writing for some producer who already knows all the story beats because he pitched the idea to you. The moment your script hits someone’s eyes will be the first time they’ve seen it. For that reason, you should always go for the gold. Find a way to give us a great opening scene that TELLS A STORY – limitations be damned. If you do that, you not only start your script off right, but you instill trust in the reader that you’re here to entertain them.