Genre: Thriller

Premise: A newly married couple move back to the husband’s home town, where they run into his old high school classmate, a strange man who used to be known as “Weirdo.”

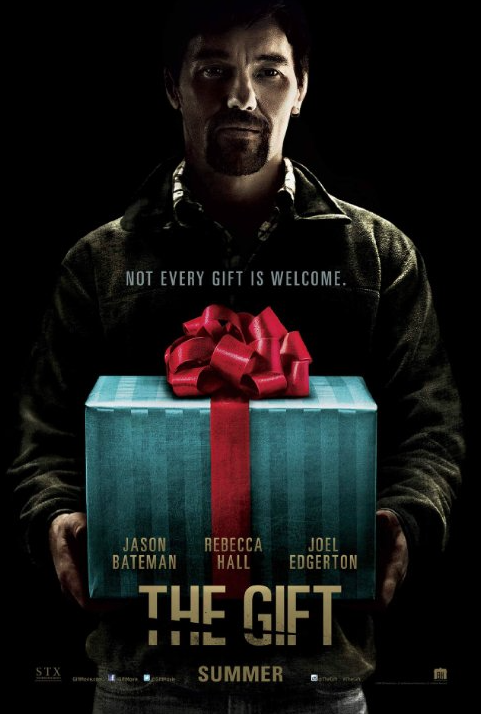

About: Australian actor Joel Edgerton clearly has bigger plans for his career than just preening for the camera. Edgerton wrote, directed, and starred in today’s script, which hits theaters in a couple of weeks. Because this is a contained low-budget thriller (and sort of horror), it is of course produced by Jason Blum. If you want to know how to get Blum to buy YOUR script, well, I can’t give you a definitive answer. But I can tell you why he responded to this script: “I was very compelled by this notion of, you slight someone in the past and you think they’ve forgotten—and they haven’t. And I really like the idea that the way that person may, or may not, be getting revenge is by giving you a series of gifts that start off nice and grow meaner and meaner and meaner. I thought those were very relatable things.” Notice how Blum’s responding to the “concept” nature of the pitch. The “gift” part. That’s how he realized he could market this. Which is why, not surprisingly, he had the title changed from “Weirdo” to “The Gift.”

Writer: Joel Edgerton

Details: 115 pages (May 2014 draft)

They just don’t make these films anymore, do they? It used to be that a good thriller would fetch an A-list star and ensure a 2000 screen release. But now, unless the idea is incredibly clever (Gone Girl) or somehow fetches a great director (Gone Girl), these films go straight to Digital. Like the 2014 film, The Guest. Solid movie. But went straight to Itunes.

And it’s too bad. Because I miss these films. They’re a nice vacation from Fancy Capes McGuillicuty and his band of merry freak friends releases (Avengers 1&2).

And I have a theory why they’re disappearing which I’ll share with you after the plot breakdown but the good news is, it looks like “The Gift” (“Weirdo”) is one of those rare thrillers that’s getting a wide release. Or, at least, I just saw a giant billboard promoting it, which would suggest it’s getting a wide release. So there must be something special going on here, right?

“Weirdo” begins when recently married couple Simon and Robyn move into a new home back in Simon’s old town. While the two are out furniture shopping, they bump into Gordo, an old classmate of Simon’s from high school.

Gordo seems excited to see Simon but something in Simon’s reserved reaction tells us there’s more to this story. In the following weeks, Gordo keeps finding reasons to stop by, and while Robyn finds it endearing, Simon is pissed. Especially when Gordo starts stopping by when he’s at work.

It isn’t long before Simon’s had enough, and tells Gordo that they don’t want him around anymore. But his absence only seems to create more stress. Robyn becomes convinced that, because they upset Gordo, he’s going to do something bad.

Eventually, Robyn learns that Simon’s not telling her everything about what happened back in high school. Apparently, Gordo was caught having sex in a car with an older man, and the fallout led to everyone making fun of him and him having to leave school.

At least, that’s the story told at first. The more Robyn looks into this, the more she realizes it may not be Gordo she should fear. It may be the man she shares her home with.

So here’s the conversation I’ve been having with a lot of writers lately – writers who are trying to figure out what to write about. Movies are becoming more and more about “moving” than they ever have before.

The barrier for entry on your average weekend film is getting larger and larger. Films need to look more impressive than ever before. They have to look bigger than they have in the past. They have to be flashier.

And the key ingredient to creating all of these things? – MOVEMENT.

We need to see a lot of movement on screen. Moving from location to location. Characters moving from one place to another. Moving in cars. Moving in action scenes. There has to be a sense of movement on the screen. And this is always how movies have looked best. But you used to be able to get by with more stillness in film. Nowadays, it’s tough.

If you have a trailer where shot after shot is people standing around, it looks like not a lot is happening. And many people equate that with boredom. Some trigger goes off in their head that says, “Movie I’d rent. But not go see in the theater.”

The lone exception to this seems to be the horror film. And the reason the horror film can survive in this environment is because the writer has the power of fear on his side. He can create fear – one of the most powerful emotions an audience can have – in the smallest and stillest of venues. And actually, it seems like the smaller the room, the scarier things get. In that way, the stillness, the limited locations, actually aid the movie.

But the contained (or low-budget) thriller isn’t exactly horror. It’s a form of horror, but it lacks those big scares that only a horror film can provide. And that’s why these films are getting marginalized. That’s why they’re getting sent straight to video. The Gift seems to be one of the few films who have maneuvered around this pitfall.

So how was it? Well, the danger when you’re writing a script like this is: Is there enough in the tank? Do you just have a scary guy coming around and being scary and that’s it? Because if that’s the case, we’re going to be bored by the midpoint.

You need to find an extra gear – one more big plot point – to get an idea like this to the finish line. And while Weirdo’s plot point isn’t a slam dunk, it’s good enough to finish the race.

What is that plot point? We need to get into spoilers to broach it so avert your eyes if you don’t want to know. The coup of this script is that Edgerton makes us start questioning who the real “weirdo” is.

About 3/5 of the way into the story, Robyn begins to realize that her husband isn’t telling her the whole story about what happened to Gordo. And this does two things from a storytelling standpoint. First, it creates a mystery we want the answer to. We want to know what happened to Gordo. And second, it makes us start questioning Simon. Is he the real danger here?

So it’s kind of cool because the first half of the script creates this “impending sense of doom” around the character of Gordo. And the second half creates an “impending sense of doom” around Simon. If they only would’ve stayed with the first of these characters, I don’t think the script could’ve lasted. Trying to ride one single fear through an entire movie is hard to do.

This is actually the problem The Guest had. Cause it was kind of the same situation. A guy moves in with this family who we feel is dangerous. And that’s really cool on page 15. But it gets kind of stale by page 85. He was just more crazy than he was earlier.

So while Weirdo wasn’t perfect, that story choice made it a movie. It’ll be interesting to see how the film does because it truly is a “still” type movie. And without that straight-horror tag, that’s going to be a hard sell. We’ll have to see.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Always pay attention when an actor writes a role for him/herself. It gives you direct insight into what kinds of characters actors want to play. Which here is someone scary, unpredictable, and a little bit crazy – all things that allow an actor to display their acting chops.

What I learned 2: For British and Australian writers, there are no “queues” in the United States. Only lines! I bring this up only because I see it a lot. And I don’t mind it if the movie is set in Australia or Britain. But if you’re going to set it in the U.S., make sure it’s a line!

Ant-Man is the riskiest studio bet of the year. Did its rocky development process ultimately doom it? Or did the little superhero film that could pull off a cinematic miracle?

Genre: Action/Heist/Super-hero

Premise: A high-profile burglar is recruited by a famous scientist to break into his old company utilizing a cutting-edge shrinking technology.

About: When newly-formed Marvel Studios came up with their game plan (create an interconnected universe of movies just like they’d done with their comic books), Hollywood laughed. And why wouldn’t they? The town is infamous for ignoring any model outside of the ones they’ve carefully cultivated themselves. Boy were they thrown when the prodco then rode their model to become the most successful in the business. But even the biggest Marvel supporters did a double George Takei when the caped company announced they’d be making a film about Ant-Man. The character seemed to embody the opposite of what made super-hero characters so cool (being big, strong, having powers, not talking to ants). So putting 130 million dollars into a super-hero version of “Honey, I Shrunk the Kids,” seemed about as smart as casting Rick Moranis as Thor. Complicating the matter even further, geek superstar director Edgar Wright (Shaun of the Dead, Scott Pilgrim vs. The World), who had been developing the movie for ten years, was axed by Marvel Don, Kevin Feige, at the last second. Rumors were that Wright’s vision of the story was too weird and wouldn’t fit into the Marvel universe. He was replaced by a director with only slightly more notoriety than your average craft services table – Payton Reed. This coincided with comedy writer Adam McKay (Step-Brothers, Anchorman) coming in to rewrite the script with the star of the film, Paul Rudd. All of a sudden, the industry wondered whether Will Ferrell would be playing the film’s villain, More Cowbell. While the movie didn’t do typical Marvel-like numbers, it made a respectable 57 million dollars this weekend, and introduced the world to one of the more unique super-heroes in Marvel’s antsenal.

Writers: Edgar Wright & Joe Cornish and Adam McKay & Paul Rudd. Story by Edgar Wright & Joe Cornish. Based on the comic book character created by Stan Lee & Larry Lieber & Jack Kirby

Details: 110 minutes

Ant-Man may seem like a tiny movie in the grand scheme of things, but there’s actually a lot to learn from the film and its much-publicized development. The biggest thing I took away from it was how hard it is to do something different in this business.

As I’ve been saying for awhile now, if superhero movies are going to survive, they’ll need to evolve. We’re getting to the point where a new super-hero film is coming out every month. It’s only a matter of time before the Marvel methane bubble bursts.

That’s why Feige is introducing a character like Ant-Man. It’s why DC decided to make Suicide Squad. It’s why we’re getting a foul-mouthed vigilante super-hero in Deadpool. It’s why Warners feels they need to put both of their prime-time super-heroes in the same movie. “Different” may be the only way to survive in this oversaturated market.

But watching the delusional development of Ant-Man go down proves just how terrified Hollywood is of “different.” They said to themselves, “We already have a super-hero who’s different. Do we want a director who’s different too? Wouldn’t that make things… too different?” So they got rid of Edgar Wright and brought in the most vanilla director this side of an oversized teaspoon.

What was the result? Well, a pretty vanilla movie. A lot of safe choices. A lot of film school 101 shots (oh, here comes that establishing crane shot that starts 1 story high then cranes down to street level just as the car door opens and our hero gets out!).

But what’s interesting about Ant-Man is that it still contains echoes of Wright’s original vision. So we get these moments of divine inspiration that seem like they belong in a different movie. And that’s because they’re from a different movie – the movie the previous director wrote. I mean, I’d be very surprised if Reed had anything to do with the kid’s train set action piece in the film’s climax.

So what’s Ant-Man about? Glad you asked. An old scientist named Hank Pym, who used to run one of the biggest companies in the world, becomes concerned when his successor, the potentially crazy Darren Cross, shifts all the company resources into creating shrunk-down super-soldiers who can infiltrate enemy lines without being noticed.

Little does Cross know, Pym figured out how to do this 50 years ago, and already has one of these super-soldier suits, which allows whoever wears it to shrink down to the size of an ant. Fearing Cross will use the technology for evil, Pym recruits local burglar Scott Lang to wear his suit, sneak into his old company, and steal Cross’s prototype suit, a jacked-up version of the Ant-Man suit code-named “Yellow-Jacket.”

Lang trains with Pym and his hot daughter, Hope, who happens to work with Cross. There’s some sexual tension there. We learn that Pym and his daughter have a strained relationship. Oh, and let’s not forget that Lang learns how to work with and control different species of ants to aid him in his heist. In the end, Cross catches on to what’s happening, hops into the Yellow Jacket suit, and the two micro-battle their way to a sub-atomic climax, which is the same way most of my sexual exploits end.

While the execution is freakishly vanilla-extract throughout the bake sale that is Ant-Man, there are a few lessons to learn here. For starters, in the blockbuster world, you want to try and find ideas that allow you to do things that haven’t been done before.

Having super-hero battles take place on a living room rug is a very unique set-up. We haven’t seen that before and it allows you to try things that haven’t been done in this genre. This doesn’t apply exclusively to super-hero movies either. You should be looking to do this with any movie idea.

And often that opportunity is right under your nose. That’s because people see genres the way they’ve always been, not the way they could be. When I say “super-hero movie,” you probably think capes and large city battles, right? Why? Why can’t a super hero battle take place inside the hard drive of a desktop computer?

Your job, as a writer, is to look to the future, not the past. Find the angle that makes a well-established genre fresh. People were making the same freaking Godzilla movie for 40 years until someone decided to tell the story from a hand-held camera POV (Cloverfield). That fresh new angle is there for the taking. Take it!

Next up, super-hero movies don’t have an official format outside of maybe “origin movie.” But origin stories have become so standard, audiences are bored with them. For this reason, you want to look for a genre within the genre.

Ant-Man’s smartest decision was becoming a heist film (one of Wright’s ideas). Once you have a genre, you can go back through all the other movies that have operated in that genre, see how they did it, and use their structure as a blueprint for your own movie.

This is the same thing the insanely popular “Captain America: Winter Soldier” did. They made that movie a conspiracy thriller. This allowed them to go back to movies like “Three Days of The Condor,” see how they made them work, then use the same principles to make their film work.

If you don’t have a genre to guide your movie, you’re flying blind. You’re making up shit as go along and hoping it works. Every once in a long while, someone pulls off a miracle, but usually if you don’t have that blueprint to guide you, you crash and burn.

Finally, commit. It doesn’t matter what kind of story you’re telling. If you don’t commit to it 100%, it’s not going to work. Ant-Man is, in a lot of ways, a ridiculous idea. I mean, Scott Lang chums it up with ants and trains them to help him execute a heist. But you know what? That’s the story you chose to tell. If you’re scared to tell that story? If you dance around it? The script will never work. So you gotta commit. And they did.

And that goes for ANY idea. When I read “Bubbles,” the script about Michael Jackson told through the eyes of his chimpanzee – that script doesn’t work if the writer thinks his idea is too weird and decides, midway through, to switch the point of view over to Jackson. This is your premise. Embrace it 100%. That’s the only way a weird idea works.

And you know what? That commitment is what led to Ant-Man’s best scene, the showdown between Ant-Man and Yellow-Jacket in a child’s bedroom. A writer who was scared of this idea surely would’ve looked for a “cooler” place for Ant-Man and Yellow-Jacket to fight. Maybe in one of those industrial warehouses we never ever see in action movies (note to all: this is sarcasm. There is nothing Carson hates more than action movies that end in industrial warehouse locations). So despite many of Ant-Man’s faults, I have to give them credit for fully committing to the idea.

To sum up, I’m really torn on this movie. On the one hand, I’m so happy that Marvel took a chance and tried something different. On the other, I’m disappointed they neutralized that choice by going with such a vanilla director. I mean, this appeared to be shot with the same lens package and character blocking that gave us Reed’s, “The Break-Up.” And I’m not saying Wright would’ve saved this. In reality, he probably would’ve made it too weird. But this movie needed a director (and writers) better than the ones it got. It was okay. But it could’ve been so much better.

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of a matinee ticket

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Embrace the movie you’re trying to write no matter how strange it is. If you’re scared of it, if you try and give us the sanitized version of it, the audience will feel let down. Imagine Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind without the beach house crumbling around our characters. Life of PI without the tiger on the boat. Inside Out is a wonderful example of how to do a weird/unique idea right. It committed to an extremely complicated working model of the mind that included physical embodiments of feelings, memory balls, islands of happiness. I mean they went ALL IN. In general, when you’re writing something weird, anytime you put something down on the page that could be considered “safe,” press delete, go back, and give us the more daring version.

I haven’t slept in three days. But that’s not going to stop me from offering some amateur screenplays! Rhyme alert. This is the section of the paragraph where I usually write something witty or funny. I will leave that up to you though. Write something funny for me in the comments and I’ll insert the best sentence. huhuh. “Insert.” We’ve got some good scripts this week, too. It should be an entertaining battle. Read, vote, critique!

Title: ENDWAR

Genre: Action-Thriller

Logline: When every major city across the United States is attacked by an overwhelming paramilitary force, a Special Ops team has less than 24 hours to breach the war zone of New York City in a last chance attempt to retrieve a device that could turn the tide of war, before the US government takes drastic action and initiates the ‘Endwar’ protocol.

Why You Should Read: Hey everyone! I was recently inspired by a similar type of script that was recently featured on Amateur Friday with it’s use of artwork, so I’ve decided to do a similar thing myself, featuring the images on standalone pages, rather than behind/beside the text (so don’t freak out at the page count, it’s not as long as it might look). I have long had a fascination with war stories, but where this is different is that it takes place on American soil (something only very few films have explored in the past). The script was kind of an experiment in going big, unlike my previous scripts which were much smaller in scope. I want to take this script to the next level, with your notes Carson, and with the notes of the SS community. Thank you to everyone who can help.

Title: Kill Order

Genre: Action thriller

Logline: A retired CIA hitwoman is given 72 hours to assassinate a heavily-guarded African despot before her own husband and daughter are executed.

Why you should read: Kill Order is a marketable action thriller with a clear GSU and a kick ass female protagonist (studio bait right now) capable of leading a Taken-style franchise. The script has been optioned twice in recent years but I’m hoping that this latest draft will take it to the next level. Any comments / suggestions from the Scriptshadow readers would be greatly appreciated!

Title: God Dammit!

Genre: Action/Comedy

Logline: After discovering that her oven is a portal to the afterlife, a grieving loser teams up with her psychotic friend to rescue her dead brother from heaven.

Why You Should Read: I’ve been writing for awhile now, and it’s very rare that I write something where I think, “This is actually good.” But, I really feel good about this. And, I know every writer thinks their script is the best thing ever written. But, I really feel good about this one. It’s a big, broad comedy with real characters, real emotions, and real ideas behind it. And, it’s got a fight with a dead Jimi Hendrix if that’s any incentive.

At the very least, I need to know if it sucks.

Title: Virulence

Genre: Action, Horror, Sci-Fi

Logline: After a mysterious virus ravages Los Angeles, a father and daughter trapped in the evacuated city attempt to escape from a horde of infected canines.

Why you should read: I moved to Los Angeles to pursue acting and creative writing. This is my attempt at a feature-length screenplay. The premise is World War Z meets Cujo. Here’s a tagline for the movie: “Welcome to the dog days of summer.”

Title: The Medusa Room

Genre: Contained Thriller

Logline: After an accident exposes him to an unknown contagion that leaves its victims permanently “inert” rather than dead, a once-renowned doctor must use the limited resources at his disposal to solve a mysterious outbreak and prevent a worldwide plague- all while trapped inside the world’s most advanced quarantine chamber.

Why you should read: I knew I had a killer concept, and wanted to make sure I was making the absolute most of it. As such, I purchased coverage from Carson to look at what amounted to my first serious draft (from Carson: you can learn more about consultations here). His feedback was by far the best education I’ve ever received in the art of screenwriting, and that feedback in turn led to a page one rewrite. After some positive reception to that version from fellow writers, I decided to hit the cold query circuit. Within eleven (!) minutes I had my first of several read requests…

And that’s when the real work started. Those read requests came from some of the best managers in town, but resulted in passes of both the silent and vocal (but polite) nature. Still, though, I refused to give up, and went looking for further feedback from fellow writers/readers- feedback I’ve used to hone the screenplay accordingly.

I know that some of the most beloved scripts required years of rewrites (see Future, Back to the) before they landed on solid ground, but I feel this one is worth the effort. It’s a high concept that balances really cool tech with really tight character development inside of a tense, ticking-clock scenario, and it’s a movie I’d watch in an instant. I think a larger audience would, too, and I’m open to any suggestions on how I can maximize the potential of my idea.

This has been one of the busiest weeks for me that I can remember. I was going to rush a read of amateur script, Leadbelly, and put a review up, but I don’t think that would be fair to the writer. I just wouldn’t be able to give it the time and attention it needs. So as hard as this is to say, there will be no amateur review this week (I’ll put up Leadbelly next Friday).

The silver lining here is you have MORE TIME to work on your Scriptshadow 250 entries. The deadline is now 13 days away. If I were you, I’d catch one of the new flicks this weekend, Ant-Man, or Trainwreck – both look good, then write yourself into submission. It’ll all be worth it when we’re planning what you’re going to wear to the premiere of your movie next year.

Make sure to check out yesterday’s article about slow burns. It might be the final piece of the puzzle for your screenplay. I will try and post amateur offerings for tomorrow morning but no promises. I’ve barely been able to come up for a non-work breath of air over the last 96 hours.

One of the big complaints with last Friday’s amateur screenplay was that it started too slow. In response to this criticism, the writers, Greg and David, turned it around on the readers. In their opinion, it was the reader’s fault for being so impatient. They were going with a “slow burn” and if people couldn’t handle that, they weren’t reading the script properly.

I’ve encountered this reaction from a lot of writers over the years. If I point out that something’s too slow, they say they’re going for a “slow burn,” as if that phrase is a magical suit of armor that allows anything that’s slow or boring a free pass. It’s as if they believe they’ve earned some right (maybe because they’ve been at this screenwriting game for a while?) to drag us through forty minutes of plot and character set-up before they get to the “good stuff.”

Unfortunately, that’s not how a “slow-burn” works. Slow-burn is a technique. Its purpose is to build a slow and steady interest, using each scene to pull the reader further into the story. As opposed to, say, Raiders of the Lost Ark, which yanks you in right from the start, a slow-burn is more like a seduction. You’re not even aware it’s happening until you’re abolustely infatuated with the person.

So what’s the key to a good slow-burn? It’s pretty simple actually. SUSPENSE. If you can imply or outright tell the reader that something intriguing is coming down the pipeline, they’ll stick around to find out what it is, regardless of how slow your script is. If there are no hints at an exciting future at all – if you’re, once again, just setting up characters and only covering the present moment of your story, your reader is likely to get bored.

Suspense is sort of like making a promise. You tell your reader, “I’ve got something cool coming around the corner. Stick around to find out what it is.” And this is where, probably, the biggest mistake is made in terms of writing a slow burn. You see, in order for that promise to work, THAT PROMISE HAS TO BE GOOD.

For example, if my mom said to my friends and I, “Okay, everyone, if you’re patient until I finish my work, you all get an apple,” that’s not exactly an exciting promise. I’ll be easily distracted, looking for ways to get into trouble. But if she says, “If everyone waits until mommy finishes work, I’ll take you all out for ice cream,” that’s a promise that resonates. I fucking like ice cream.

So let’s go back to last Friday’s script. My guess is that Greg and David would’ve pointed out that the early scene where their political figure being murdered and replaced by a doppleganger was their “promise” – that’s the suspenseful story point that allowed them to take their time going forward. They’re right in saying it was a promise. But the promise was more of an apple than it was ice cream. We didn’t know this political figure. The act itself was kind of cliché (we’d seen this sort of thing happen in Mission Impossible movies and the like hundreds of times before). Just like any screenwriting technique, a slow burn must be pulled off originally, creatively, and with imagination. If your promise is an uninspired one, you can expect an uninspired reaction.

And this extends beyond the world of slow burns to choices in general. If your choice is standard or cliché or not nearly as exciting as you think it is, it’s going to land with a thud. And worse, a bad choice causes the elements around it to fall apart as well. It creates a domino effect. For example, we talk about conflict a lot. You want to inject some form of conflict into every scene to give it life. But let’s say, 30 pages previous to that conflict-laden scene, you created a cliché unlikable main character. Well, 30 pages later, putting that character in a conflict-heavy scene won’t matter, no matter how well the conflict is written. Because we already don’t like this character. We don’t care about their journey. Therefore, everything around that character crumbles as well.

And I think this is one of the biggest learning curves in screenwriting. Is finding out what’s a compelling choice and what isn’t. If something feels too familiar, too cliché, too unimaginative, it doesn’t matter what device you’re using to try and keep the reader’s attention. It probably won’t work. That’s why people who stick with screenwriting tend to be better than people just starting out. Their bar is higher. They’ve already tried all those boring choices. They learned what doesn’t work. Therefore, when they write a script now, they challenge themselves to come up with fresher more interesting ideas.

Getting back to slow burns, one of the most famous slow burns is The Sixth Sense. Some might even argue that the entire movie was a slow burn. The film never really accelerates its pace. But it worked because the elements included in the burn were compelling ones – namely the mystery behind this child. That was a cool promise. This kid could see ghosts that no one else could. Was he seeing things? Were they real? Could this man help him? The promise (as well as the elements SURROUNDING the promise – like good characters) was very compelling.

Another thing with slow burns is you want to hedge your bets. Try not to give us just one promise (unless that promise is gigantic), but rather a handful of them. And suspense shouldn’t be the only tool you use. You can also, for example, use something called “leading.” This is where you literally tell us something is coming down the pipeline. This creates a natural desire in the audience to stick around until we get there.

So let’s say you’re writing a small town drama and want to start with a slow burn. You might “lead” the audience by mentioning an upcoming fair. Just have your characters talk about “the big fair” that’s coming up this weekend. It doesn’t have to be a mystery or some huge plot point. But just the fact that we know the fair is coming is going to create a desire to get there. This is preferable to implying that nothing is coming. Because then there’s nothing for the reader to look forward to.

And you can use multiple leads, small and large, to create little checkpoints the audience will want to get to. For example, if your script starts with a married couple who clearly aren’t happy with each other, you could lead by having the wife call the husband at work and say she needs to talk to him about something important tonight. This is a conversation that sounds like it’ll be interesting, so we’ll want to stick around until it happens. And again, a lead doesn’t have to be singular. Who’s to say you can’t have the fair lead and the “we need to talk” lead in the same screenplay?

Another way to make a slow-burn work is mystery. A murder has been committed. A child has gone missing. The power has gone out in town. Every dog in town has run away. Someone comes home to find that their bedroom has been ransacked. Mysteries are one of the most powerful tools (and another type of PROMISE) in keeping the reader’s interest. Much like leading, they create a desire to find out what’s going to happen. If you’re going to have a really slow burn for the first 40 pages of your script, starting out with a good mystery can go a long way.

Another good “slow burn” tool is a looming sense of dread. If we get the feeling that something bad is just over the horizon, we’re likely to stick around. This approach actually works hand-in-hand with a slow burn – since the very nature of “looming” is deliberate. Once horror sensation “It Follows,” establishes the rules of its universe, it rests very comfortably on the “looming sense of dread” approach. Anybody anywhere could be one of these demons. So we fear it’s only a matter of time before one of them comes along. Most people who watch that film will tell you it was slow. But they still loved it. Why? Because the entire story was built around this looming sense of dread.

Now that we have a sense of what TO do to create a good slow burn, let’s talk about what not to do. When I first started reading scripts, I was shocked by just how SLOW most of them were. And so I was giving readers a lot of this note: CUT OUT ALL THESE USELES SCENES! GET TO THE STORY FASTER! And on a certain level, that’s good advice. Screenwriting is about cutting out the unnecessary – getting to the meat as soon as possible.

But a lot of times, that note wasn’t addressing the underlying problem. It wasn’t so much that we were taking too long to get to the story. It was that the writer wasn’t doing anything to make the lead-up to the story interesting. Again, the writer was just setting characters up, setting plot up, conveying exposition. All of these things are necessary, of course. But what’s required (which most writers don’t do) is to do all that IN AN ENTERTAINING WAY.

So they weren’t setting up mysteries, they weren’t leading, there was no impending sense of doom, there was no suspense, no promises. Or if there were any of these things, they were cliché or obvious versions of them, which, while better than nothing, still ineffective. So it’s important to recognize that when someone says your script is “too slow” or not getting to the story fast enough, it might not be the actual number of pages that’s the problem. It may be HOW YOU’RE WRITING THOSE PAGES. It may be the fact that you haven’t used any tools to give us a reason to keep reading.

Another common ineffective solution to a slow script is the classic, “Start with a big flashy action scene.” Writers think that if they blow us away with some super-awesome action scene to start off, it will allow them to take their time for the next 30-40 pages and slowly set up their story.

This is faulty logic for a couple of reasons. First, a big action scene can be just as boring as a small talky scene. In fact, action scenes can be some of the most boring to read in the entire script. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve read, “And then the car CRASHES into the pole, spins, then REVS up again, NEARLY GETTING CLIPPED by a TRAILING COP CAR, before RACING OFF.” You know how boring it is to read 10 pages of that?! So don’t think of these scenes as magic beans by any stretch of the imagination.

And second, it still doesn’t solve the underlying problem. Let’s say you have a slow burn where you aren’t leading, setting up mysteries, creating any suspense, or injecting an impending sense of doom. That doesn’t just magically get fixed because you placed an action scene before it. You still need to address the real problem – which is offering the reader a series of promises. Letting them know that good things are coming around the corner.

I guess the final question here is: When does the slow burn end and the story begin? And I think the answer to that question is: WHEN THE GOAL OF THE MAIN CHARACTER IS INTRODUCED. Once you give us that goal, you’ve shifted over from “slow burn setup” to “full-fledged story.” Take the recent hot spec sale, Collateral Beauty. We start by seeing this CEO who mopes around his office all day building giant domino trails. That’s the first mystery to keep us hooked during the slow-burn phase (Why is he doing this? What happened to this man?). Then we learn that his employees are going to try and oust him so they can sell the company. That becomes the MAIN GOAL that drives the story. We’re no longer in “slow burn” phase from that moment on.

I know this is a lot to take in so let me just finish with this. In order for a slow burn to work, THERE HAS TO BE A BURN. Too many writers – especially writers just starting out – only give us the “slow.” And that’s where they run into trouble. Slow-burns are actually one of the most nuanced forms of storytelling there is. It takes a lot of skill to pull them off. Start by mastering the basics first (introduce a strong goal for your main character quickly) and once you’ve figured that out, you can play with suspending that main story and adding some slow-burn elements before we get there. It can be done. It just takes practice. Good luck!