Is “The Hangover” one of the best ideas in Hollywood history?

Is “The Hangover” one of the best ideas in Hollywood history?

Are you aware that 90% of all scripts are dead before the writer even writes the first word? Welcome to the “bad idea,” the quickest and most terrifying way to destroy a screenplay. The worst thing about the bad idea is that, after coming up with it, you are beholden to it for the next year, two, three, five. You could spend countless hours and endless rewrites on something that has no chance of success no matter how much you put into it.

Now some might argue that struggling through your bad ideas is part of the learning process. Your bad ideas are where you practice, where you fail, where you grow. You don’t have enough experience yet to know that the idea is weak, so you keep fighting the script, and in the process, learn how to write scenes and characters and dialogue.

But bad ideas are not exclusive to young writers. Anyone can have a bad idea. Animal Kingdom was one of my favorite movies a few years ago. It was raw and fresh and different. I recently watched the director’s newest effort, “The Rover.” As far as I can tell, it’s a dystopian tale about a man who wants his car back. Now we know David Michod can write and direct. We saw it in his previous film. But once he locked himself into that bad idea, there was nothing he could do. The idea wasn’t good enough to sustain a movie.

Now some of you may be saying, “Judging ideas is pointless.” “Whether an idea is good or not is subjective.” That’s sorta true. But I’d argue there are lots of ideas we can all agree on. Take, for example, these two that I just made up…

1) Payback – A famous White Supremacist Leader wakes up in the middle of a gang-infested African-American neighborhood.

2) The Tech – A well-known but reclusive tech blogger wakes up in the middle of Silicon Valley.

Which one of these ideas is better? I’m guessing that we’re all in the same boat here. The first idea knocks the second idea out of the park. Why? Let’s take a closer look at both ideas to find out.

The first thing you notice in Payback’s logline is CONFLICT. There’s a ton of it. A white supremacist in the middle of a predominantly black ghetto tells us there are going to be a number of confrontations, and they aren’t going to be pretty. Next we have stakes. There’s a good chance that our character’s life is in jeopardy. Finally, a good idea inspires the reader to ask questions. “Will he get out of this?” we ask. “What will they do if they catch him?” Questions put the reader in the story before they’ve even read it. If you can put readers in stories they haven’t read yet? You’re doing your job as a writer.

Now let’s check out The Tech. A reclusive tech blogger is dropped inside Silicon Valley. Doesn’t sound like there’s much conflict here, does there? If he’s a tech blogger, he probably knows a lot about Silicon Valley and should have an easy time getting out, right? Also, if he’s reclusive, will people even recognize him? And are those people even on the street? Probably not. This is sounding less and less interesting by the second. Actually, now that I think about it, does he even want to leave? As you can see, when there’s no problem, there’s no reason for the hero to act. So unlike our white supremacist, our blogger might decide to head to Starbucks and grab a coffee. Why not?

So the first lesson in writing a great idea is that there needs to be some sort of problem, and that problem needs to cause some ongoing conflict in the storyline. Stakes are important as well, and should come naturally if you have conflict in place. Alright, let’s see if this holds up with a few of the best ideas ever to grace the silver screen. Notice I’m not saying these are the best movies. Just the best ideas.

Jurassic Park – A group of people are trapped inside an island theme park for cloned dinosaurs.

The Hangover – Three groomsmen must retrace their steps after a black-out drunken night in Vegas to find the missing groom and get him back to his wedding on time.

Hancock – A depressed alcoholic super hero must fight off his inner demons in order to save his city from a rapidly growing crime wave.

Rear Window – A wheelchair bound photographer confined to his apartment starts watching his neighbors and becomes convinced that one of them has committed a murder.

Say what you want about these films. These are all quality movie ideas. And they all fall in line with our “good idea” requirements. A problem is introduced that creates conflict. The stakes are high (except for, arguably, Rear Window). And they get us asking questions (The Hangover and Rear Window, especially.) Now, here are a few amateur loglines I found on the internet for comparison.

Seven-Fourteen (drama) – A psychiatrist during the 1970s finds himself selling prescriptions to a vicious mob boss while being hunted down by an FBI agent.

The Quest For Triaba: Secrets of the Forbidden City – After Lucas and Alexa travel with Mattack to the Forbidden City, Zetra and Connor try to find their own way into the Forbidden City. Along the way, these different groups of survivors meet up with some of the Wasteland’s most hideous people. Can Zetra and Connor make it to the Forbidden City? Can Alexa and Lucas fight off the terrible Carga? What will happen?

Cold Snap (drama/thriller) – During Christmas season – three young, bored and jobless teens hatch a plan to rob a family man’s traditional takeaway shop.

A Mind Reader (Horror) – A serial killer who can read minds is terrorizing Las Vegas. Emma, a troubled young girl is receiving visits from the ghosts of his victims. She seeks solace with a group of young teenage psychics. For differing reasons, they decide to find the mind reader themselves. The only trouble is, it’s hard to stay a step ahead of someone who can read your mind.

Hmm, my theory for good ideas is crumbling as we speak. Three of these ideas do just as our professional loglines did – they introduced a problem. Seven-Fourteen has the FBI hunting our hero down. The Quest for Triaba has the terrible Carga wreaking havoc. A Mind Reader has a serial killer on the loose. The only one that doesn’t have a problem is Cold Snap.

And yet, it’s hard to argue that any of these ideas are any good. If I were pressed for the best idea, I’d probably say Seven-Fourteen. But it still feels weak. In order to figure out what’s not working here, we may need to dissect each idea individually. Maybe then we can add some more rules to our list.

Seven-Fourteen (drama) – Okay, so like I said above, the writer creates a problem here. A psychiatrist is being hunted by an FBI agent. But there’s something very bland about it. FBI agents are in every single movie. What’s so special about this one? Not only that, but the elements don’t come together in a cohesive manner. What do the 70s have to do with this idea? How would it be any different if he were selling prescriptions today? And why would the FBI hunt down a psychiatrist? Isn’t the way more important catch here the mob boss? This idea is missing both excitement and logic.

The Quest For Triaba: Secrets of the Forbidden City – At first glance, this appears to be more of a logline problem than an idea problem. But logline or not, the idea is unfocused. I mean the title is “The Quest for Triaba,” yet there isn’t a single mention of Triaba in the logline. How could that be if Triaba is the goal driving the story? It’s pretty clear to me what isn’t working about this idea. It’s unfocused and confusing.

Cold Snap (drama/thriller) – The problem with Cold Snap as an idea is that there’s no story problem. Our main characters decide to do something because they’re “bored.” Boredom is rarely a good starting point for a story. You want a character who’s in peril, who’s in trouble. That way their motivation is strong. They must act to solve a problem. Also, this idea, like Seven-Fourteen, is too plain. Look at a comparable idea done better, the Sidney Lumet film, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead. “When two brothers organize the ‘perfect crime,’ robbing their parents’ jewelry store, their mom is accidentally killed during the robbery, leading to the implosion of the family.”

A Mind Reader (Horror) – Surely an idea about serial killers who can read minds is good, right? Not really. Whenever you complement strong elements, you want to do so with irony. The Billy Bob Thorton Christmas movie isn’t called “Dolphin-Loving Santa.” It’s called “Bad Santa.” There’s no irony in a Santa who loves dolphins just as there’s no irony in a serial killer who can read minds. Here’s another serial killer idea – A serial killer who only kills serial killers. That’s the premise for Dexter, the HBO show. That’s an idea. “A Mind Reader” is a muddled beginning to an idea that hasn’t been explored enough. Also, once you add ghosts, the idea becomes too crowded.

Okay, so we’ve learned a few new things. An idea works best when it’s big or exciting (as opposed to bland). This seems obvious but I can’t express how often I see this mistake. The addition of irony always makes an idea better. It’s why Hancock was such a big spec sale and huge movie, despite the execution being so lackluster. The idea must be clear. The idea must be focused.

But wait a minute. Not every idea can be Jurassic Park, can it? What about movies that don’t sound good in idea form? Like The Skeleton Twins! Which I loved. The logline for that was, “Two siblings both try (and fail) to commit suicide on the same day, later coming together to try and resolve their complicated relationship.” The “problem” here is their “troubled relationship,” which is hardly the kind of big idea that drives people to theaters. And yet the movie turned out good. How can that happen if it’s not a good idea?

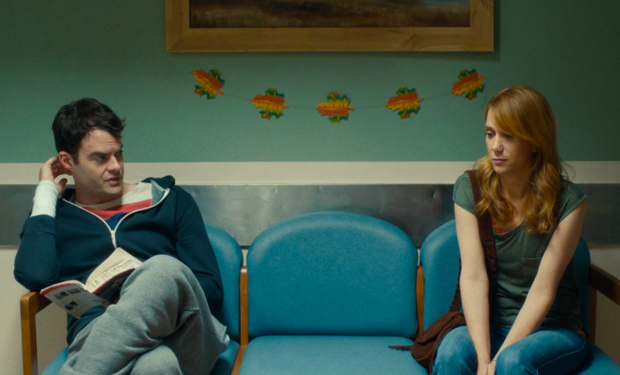

The Skeleton Twins, like a lot of indie movies, is an “execution-dependent” film, which is code for “character-driven.” These scripts are built less on ideas as they are on characters. Once you have strong characters in your script, you attract strong actors. The marketing of the film then focuses on those actors, as opposed to the concept itself. If you watch any publicity material for The Skeleton Twins, it’s all about Kristin Wiig and Bill Hader as opposed to the story. You’ll find that these scripts almost NEVER make it through the spec market because the ideas aren’t big enough. They have to be made on the indie circuit and are usually done by writer-directors.

That doesn’t mean you can’t write character-driven ideas. You just need to come up with good concepts for them. That way you get the best of both worlds. Like 2012’s Safety Not Guaranteed. A man puts an ad in the paper claiming he can time-travel and that he needs help. This is the starting point not for some Edge of Tomorrow knock-off, but an exploration of four characters and the problems holding them back in life.

All of this leads to the big question. What are the definitive traits that make up a good idea? We can never say for sure. But we’ve certainly seen crossover elements in the good ideas. Here are the big ones in list form. By no means must your idea include every item on the list, but it should definitely have a few.

1) There’s a big problem facing your hero(es) (the Nazis are trying to get the Ark of the Covenant to use as a weapon!).

2) There is lots of conflict inherent in the idea (The Walking Dead – everyone’s life is constantly in danger from both zombies and other humans).

3) There are high stakes (Jaws – if they shut down the beach because of the shark attacks, the town won’t make any money during tourist season).

4) There’s something unique/original about your idea (memory zapping in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind).

5) The idea feels big (A town and their fuel is in jeopardy from a rival band of raiders in Mad Max is a much bigger idea than a man who wants his car back in The Rover).

6) There is some irony in the idea (A king who must make an important speech has a catastrophic stuttering problem).

And let it be said that ONLY meeting the bare minimum of this criteria isn’t enough. I wouldn’t create a tiny problem to set your story in motion. I’d find something big. I wouldn’t be okay with a little bit of a conflict. I’d add a lot.

Does this article end the question of “What makes a good idea?” Of course not. Ideas are subjective creatures. What’s appealing to me isn’t always appealing to you. I thought the idea behind Dallas Buyers Club sounded melodramatic and outdated. But others liked it and that’s part of the subjectivity of this business.

With that said, you have a much better chance of creating a good idea if you follow today’s advice. What about you guys? What do you think makes a good idea? And to take that question a step further, how do you come up with your own ideas?

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A psychiatrist tasked with determining if death row inmates are mentally fit for execution encounters a strange inmate who somehow knows everything about her.

About: This appears to be one of those scripts that slipped through the awareness cracks. It did finish on the Black List last year, but near the bottom. The script sold to Lionsgate in a bidding war, and ended up with a mid-six figures price tag. The writer, Hernany Perla, had been working at Lionsgate as an exec.

Writer: Hernany Perla

Details: 111 pages

Michael Fassbender for Samuel?

Michael Fassbender for Samuel?

Now I know what a lot of you who read the “About” section are thinking. “OF COURSE HE SOLD THE SCRIPT! HE WORKED AT THE PLACE THAT BOUGHT IT!” Oh, if it were only that easy. Because only EVERYBODY in Hollywood, whether they work at a production house, a studio, an agency, or a management company, has a script they’re hawking. And while the sell rate is definitely better if you’re inside the system, I’m betting the odds are still pretty low. I’m guessing less than 1% of those working at studios sell their scripts.

The way I see it, there are two types of writers, no matter where those writers reside. Casual ones and serious ones. The casual writers think if they write ANY-thing, success will come. The serious writers do the work. They read, they study, and they write their asses off. I don’t know Hernany Perla, but judging by the quality of this screenplay? I can make a strong argument that he’s one of the latter.

The REAL advantage of working as an executive, and why these guys have a leg up on the competition, is because they read a lot of scripts. That’s their job. But it’s not just that. They’re tasked with figuring out what’s not working, then coming up with solutions to improve the script. That trouble-shooting muscle comes in handy when one’s writing own scripts.

“Revelations” follows Dr. Kayla “Kay” Margolis, a successful psychiatrist who’s been assigned to Death Row to decide if the current crop of inmates are mentally fit for execution. Of course, when these guys are facing down death and they know their only out is to plead insanity, they all try and plead insanity. Kay’s job is to cut through the bullshit.

Then Kay meets Samuel Desmet. Shaved head, looks like one of those hare krishna guys. Which is apropos, since he once led his own cult. Samuel’s on Death Row because he blew up a group of people.

Kay’s a little thrown by Samuel’s Hannibal Lecter-like charm, but she seems to have the situation under control. That is until Samuel mentions Kay’s boyfriend, Troy. There is no possible way that Samuel could’ve known Troy, and it freaks Kay the fuck out.

But that’s just the beginning. According to Samuel, he (Samuel), is a God, being reincarnated over and over again. He’s had this conversation with Kay a countless number of times already. And he needs her on his side if they’re going to stop what’s coming. “What’s coming?” Kay wants to know. “Winter.” He says with a whisper. Just kidding. He says the current Governor, who’s also a reincarnated God, is going to set in motion a series of events that will result in nuclear war. And Samuel’s the only one who can stop him.

Kay knows this is bullshit, but over the course of the next few days, Samuel keeps telling her things that he can’t possibly know. He even sends her to a library to check out a book that was written 100 years ago. It was a book HE wrote in a previous life for this very moment, to prove to her he’s real. In it, there’s a direct message to Kay. That she can no longer trust her boyfriend Troy, who’s cheating on her.

You’d think that would be enough evidence, but there’s always one thing that puts every proclamation of Sameul’s in question. With a little digging, for example, Kay finds out this 100 year old book was placed in the library a day ago. When she questions Samuel about this, he swears it’s Governor Cayman, who’s making him look like a liar so she won’t help him.

Kay only has a few more days left to figure it out, because at the end of the week, he’ll be executed. If she saves him, is she just another victim of a persuasive cult leader? Or could it be that she truly is saving humanity?

Ever since I read that Lee Child article, I’ve been obsessed with suspense. How a story’s success boils down to setting up questions and then stringing the audience along until those questions are answered. That’s pretty much “Revelations” in a nutshell. And it’s very effective. Samuel makes a statement that something’s going to happen in a few days (i.e. a security breach at a nuclear facility) And we furiously read on to see if, indeed, the event happens.

Even better, Hernany LAYERS these suspense plotlines so we always have more than one thing to look forward to. For example, Samuel says that Kay’s boyfriend can’t be trusted. He says that there’s going to be a book he wrote 100 years ago in the library. And he says there’s going to be that security breach, all before any of these answers come yet. It’s kind of like story crack. One suspenseful storyline is good. Three is great!

Another thing I liked here was that Hernany didn’t JUST rely on plot. That can happen when you write thrillers, especially thrillers like this. Everything’s about the twists and the turns and the suspense, and you can get so wrapped up in that that you forget you’re dealing with actual people here. No matter how Hollywood you’re getting with your script, you can never totally ignore character.

That’s why one of my favorite threads in the script was the cheating stuff. Once Samuel tells Kay that Troy is cheating on her, everything about their relationship is uncertain. When she comes home, she’s watching Troy closer. When he’s on the phone, she’s asking who he’s talking to. When they go to work functions and he talks to a woman, she’s wondering, “Could that be the one?” It added another dynamic to the story besides the ‘end of the world’ plot.

There was only one thing wrong with the script. When you started to scrutinize it, I’m not sure it all made sense. At first, Samuel wants to die, because he’ll be reincarnated more quickly than if he lives out the rest of his years in an institution. And once he’s reincarnated, he can try to stop Governor Cayman (another “God” who’s lived hundreds of lives). But if that’s the case, why is he saying all this gobbledy gook to Kay, making her think he’s crazy, if that’ll prevent the state from executing him?

Then later in the script, when it’s looking like he’ll escape death due to insanity, he goes to Kay and says he’s been conning her. Nothing he’s said to her has been true. This, she presumes, is to ensure the state kills him. So he can be reincarnated. That left me wondering, “Why the big show? Why not claim you’re a fraud right from the start if you want to be executed?” It just didn’t add up.

Usually, faulty logic like that will kill a script for me, but I was so insanely caught up in whether Samuel was telling the truth or not that I didn’t care. The genius of this script is you’re unsure about Samuel right up until the end. And that mystery dug its claws into me and never let go.

But the biggest reason I liked this script was that it was so damn FUN! It’s been awhile since I’ve had this much fun reading a script. There isn’t a slow page in the screenplay. Every single scene moves. It’s just good writing. This should’ve finished a lot higher on the Black List.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Never answer a question right away in a script. Every question is an opportunity to draw the answer out (for suspense). You can draw out the answer for 10 seconds. You can draw it out until the end of the script. It’s up to you. But you definitely want to draw it out.

What I learned 2: Layering suspense – Don’t just lay down one suspense thread. Layer them on top of each other so there’s always two or three unanswered questions going on at once.

Genre: Drama

Premise: A family who owns an upscale hotel in the Florida Keys sees their world turned upside-down with the re-emergence of their oldest son, the Black Sheep of the family.

About: We got another Netflix series here, this one from Damages creators Todd A. Kessler, Daniel Zelman, and Glenn Kessler. I never watched Damages cause it wasn’t my type of show. But I repeatedly heard about how well-written it was, which is why I decided to check this out. The show will star Friday Night Lights’ Kyle Chandler, as well as Chloe Sevigny and Steven Pasquale. The creators (Glenn and Todd are brothers) reportedly worked for an entire year on their pitch, which Netflix ate up. The Kessler brothers attended Harvard as well as went to film school at NYU. Not a bad pedigree.

Writers: Todd A. Kessler, Daniel Zelman, and Glenn Kessler

Details: 88 pages – First Writer’s Draft – 11/14/13

Kyle Chandler will star, presumably as Sheriff John Rayburn

Kyle Chandler will star, presumably as Sheriff John Rayburn

Here’s the problem when a business sector starts thriving. Everyone rushes into it. The excitement accompanied by this rush has the unintended effect of loosening quality control. Everyone figures there’s so much good going on, why stop it? Look no further than the boom of Reality TV. Do you remember when all you had to do to get a reality TV show was show up with a half-baked idea? Joe Millionaire! Who Wants to Marry a Millionaire? My Big Fat Obnoxious Fiance!

Okay, okay. So that’s not that far from where we are now. But you have to remember that back then there was one-tenth the number of outlets for those shows. Finally, someone realized, “Hey wait a minute. We need some quality control!”

I think there’s a little of that going on with the TV boom right now. People are so excited that TV is doing well that they’re getting kinda lazy. Take WGN’s Manhattan. What’s the point of this show??? We’re gonna diddle around with a bunch of science nerds until they blow up Japan? Do we really need 7 seasons of television to tell that story? I don’t think we do. But people are so eager to fill up these original TV slots that they say, hell, why not??

I bring this up because despite the glut of shows hitting the airwaves, we haven’t had a true breakout show in awhile. True Detective maybe? But that was more of a mini-series. The Blacklist? Ehhh… I feel like the only people who watch that are James Spader’s family. I’m wondering if that’s a result of this lack of quality control, or if we’ve just reached a point where there are more TV slots than there are good writers. Granted, I’ve read some good TV scripts this year. But writing a good TV script isn’t the same as making a good TV show. The only thing you have to go on is, have they done it before? And today’s writers have.

The Rayburn family pretty much owns one of the islands in the Florida Keys. They have a thriving upscale hotel business that has made them rich beyond their wildest dreams. Each member of the family has something good going for them. There’s John, who’s the town sheriff. There’s Kevin, who has a thriving business fixing boats. There’s Meg, who helps manage the hotel, and then there’s mom and dad, who own it. Each of them are beyond content with their lives.

And then there’s Danny. The black sheep. He’s the sibling who never follows through on his commitments. Who only shows up when he needs money. Who hangs out with the sketchy crew. And who always screws up even the most minor situations.

So when The Rayburn family has their annual Family/Hotel weekend-long party-thing, guess who’s the last one to show up (if you guess John you are a bad reader). Although I can’t say I blame Danny. The Rayburns idea of fun is holding family swimming contests and taking the canoe out for a morning paddle.

Things start to unravel at the ball-sized dinner when Danny purposefully shows up with a cheap townie in order to cause a scene. It’s revealed that Meg, meanwhile, is cheating on her boyfriend. And John is pulled away from the party where he learns that a second woman this month has been burned and drowned, this right before the big tourist season.

As is the case with all seemingly perfect families, we get the sense that this one isn’t as beautiful underneath as it is above. And this will play out in the worst way, when the family collectively makes the decision to do something unfathomable, something so terrible, that it will change their family…forever.

Chloe Sevigny will likely play sister, Meg.

Chloe Sevigny will likely play sister, Meg.

I’m going to be honest here. One of the reasons I never watched Damages was because it looked like it was written by… hmm, how do I say this? By entitled well-off, got-all-the-breaks in life Ivy League folk who write for like-minded people. It kind of had that “You’re not invited to the adult table” exclusivity feel to it. It just looked so serious and smart.

Now I admit I don’t know if it actually played that way, but the first half of KZK definitely backs this assumption up. You can feel the writers’ pedigree slithering up the page. I felt at times like I was Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network, sneaking into a Final Club where I didn’t belong. I mean where in life do people really worry about things like what table they’re assigned to for dinner. It’s dinner. Bring out the food and let’s eat!

For that reason, I couldn’t relate to any of these characters, which made it hard to care about anyone. Ironically, the only character I related to on any level was Danny, because he looked down on this elaborate lifestyle. The problem was, Danny was such an asshole that I still couldn’t root for the guy.

Luckily, as the script went on, it started to feel more like a story, particularly when the dead burned woman showed up. But it was really Danny who kept this pilot afloat. He was our only source of conflict. It was like dropping a piranha into a pool of goldfish. Everywhere he goes, he makes people uncomfortable, he changes the direction of the moment. Which was exciting to read.

A perfect example is the big dinner. Danny shows up at the table with some half-wit waitress from town and just lets her drink as much as possible. The family, who’s supposed to appear perfect to the crowd, now has this townie-bomb slurping up every apple-tini in sight, preparing to do who knows what to embarrass the hell out of them. And that certainly kept me reading.

I will put my foot down and say there’s a device I’m seeing a lot of in pilot writing that I don’t like. And I saw it here too. The writer writes a big flash-forward teaser, one that implies something bad will happen later, and then skates by the next 30 pages on the assumption that this has generated enough suspense that they can use those pages to set up characters in the most boring way possible.

The 30 pages after our teaser amount to people preparing for the party. The sequence was obviously inspired by 70s movies like The Godfather and The Deer Hunter, but (and I know this will drive Grendl crazy to hear) audiences don’t have the patience for that stuff anymore. Not unless you’re packing some plot into those pages, giving us other things to look forward to. If you go ten minutes without something happening, your viewer is checking their e-mail.

Now in an interview with the writers (something I went searching for when nothing happened for ten pages), they said this was going to be a show that no one had ever done before on TV. So I was looking for any elements to back this claim up. I could only find one. Danny keeps encountering some woman that he’s both terrified and intrigued by. She seems to show up and disappear at the oddest moments, and we begin to suspect (or at least I did) that she may have been someone Danny killed in the past. It was weird and definitely peaked my curiosity.

But then something beyond unexpected happened that made this development moot. And I’m going to get into major spoiler territory here so you might want to turn away. Here was this Danny guy – the only interesting thing about this pilot – some might say the key to this pilot working, and then at the end, the family fucking kills him! I read it three times to make sure I read it correctly. But yes, they actually kill off the best character in the script.

Now there are a couple of hints here that this could be one of those flashback-type shows. Where we’re jumping forward and backward in time a lot. Which means Danny may not be entirely gone. But I thought that was a pretty bold move from the writers, and it turned what was a slightly above average pilot into something ballsier. I like when shows show balls. In a world where so many writers stick on 17, it’s the guys that say “hit me” that win the big pot.

I remember the Game of Thrones pilot script doing something similar. After spending its first 60 pages doing nothing but setting up an endless list of characters, it wowed us with the incest/push the kid off the tower ending. So maybe this should be a new trend. The kill or maim a main character at the end of your pilot move?

I don’t know. But with the pedigree of these writers and the reports of how much Netflix loved this pitch, there should be a big push behind it. It’ll be interesting to see where it goes.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Drop a piranha into the pool. Instead of having to pull your pick axe out every time you want to dig for conflict, just create a “piranha” character, someone who IS conflict. Therefore, every scene you drop them into, the conflict writes itself. Danny was that character here.

Genre: Drama

Premise: When 30-something Milo tries to commit suicide, his estranged sister, Maggie, invites him into her home, where the two start the process of healing old wounds.

About: Writer/director Craig Johnson graduated from NYU film school a decade ago, where he originally conceived of this idea with fellow student Mark Heyman (who wrote Black Swan). The two eventually went their separate ways, coming back to the script only recently, where they re-focused it on its best asset, the brother-sister relationship. Johnson has one other movie under his belt, the little seen True Adolescents, which starred Mark Duplass. He’d been trying to get Skeleton Twins made for awhile with different packages, but it wasn’t until Kristin Wiig came on that he finally believed the movie would get made. And it did!

Writers: Mark Heyman and Craig Johnson

Details: 93 minute runtime

I actually saw two movies this weekend. The Skeleton Twins and The Maze Runner. For The Maze Runner, I tried to bring a little of that “opening day enthusiasm” typically reserved for movies like The Avengers and Star Wars. So I lugged in a big block of cheese. ‘Cause it was a maze? Like rats in a maze? The theater ushers didn’t understand the joke and told me I either needed to eat the cheese, throw it away, or not see the movie. I sighed and threw it away.

The cheese turned out to be relevant in a different way in that most of Maze Runner was cheesy as hell. Even worse, it employed the classic screenwriting mistake of making the main character ask 60 million questions: “What is this place?” “Where are those guys going?” “What happens in there?” “What’s a runner?” “What’s that noise?” “What happens if they don’t come back?” “What’s a Griever?” Word to the wise – if your main character is always asking questions, he doesn’t have any time to, actually, you know, do stuff.

The movie really wasn’t that bad. It was just generic. I hate giving that note to writers cause it sounds so vague but it’s so often the problem. Every choice feels like the first choice the writer came up with. A maze that changes. Seen it before. Spiders inside the maze? That must’ve taken a while to come up with. The lovable underdog fat kid. Oh, and let’s not forget the dialogue (Mopey character who thinks he’s going to die: “Take this [trinket] and give it to my parents when you get out of here.” Hero gives the trinket back to mopey character. “No. You’re going to give it to them yourself.”).

But the biggest faux pas is something you just can’t screw up as a screenwriter. You have to give them the promise of the premise. If you’re writing a script about a giant maze, that maze better be fucking a-maze-ing. And this one wasn’t. It basically amounted to tall ivy-covered walls with giant spiders running around in them. That’s it?? Your maze boils down to Wrigley Field meets Harry Potter?

Lucky for me, I also got my suicide on this weekend. But before I get to Skeleton Twins, I have to do some name-dropping. It was Friday night at the Arclight in Hollywood. As Miss Scriptshadow and I were heading to our theater we saw none other than KEVIN SMITH barge through the lobby (he was moving like a cannonball). I remembered that his movie Tusk was opening and figured he was going to watch his own movie. Which is kind of strange but also kind of cool at the same time.

The funniest part was as he walked through, every single person turned (around 100) and whispered, “That’s Kevin Smith. Hey, that’s Kevin Smith. That’s Kevin Smith.” I guess if there’s one place Kevin Smith is going to be a mega-celebrity, it would be at a cinema-loving theater like Arclight in Hollywood.

Anyway, we rode that excitement wave right into our suicide film, which I was only seeing because it got such a high score on Rotten Tomatoes (I’ll see anything above 90%). Usually I despise films like this. Depressed indie people being depressed, trying to commit suicide, then being more depressed. Count me out. But lo and behold, this ended up being one of my favorite films of the year!

30-something siblings Maggie and Milo haven’t seen each other for ten years. Coincidentally, on the exact same day, they both try to commit suicide. Maggie gets the call about Milo being at the hospital before she can off herself, so she goes there and asks Milo to come live with her and her husband, man-child but sincerely lovable Lance, until he feels better.

Over the next few weeks, Milo, who’s gay, reconnects with an older man whom we find out was his teacher in high school. In the meantime, we find out that Maggie, who’s trying to have a baby with Lance, is secretly taking birth control so she doesn’t have a child. She’s also banging her scuba instructor, which I guess makes the birth control a “kill two birds with one stone” type of deal.

We eventually learn that the siblings’ self-destructive ways stem from their own father jumping off a bridge when they were just kids. It seems, for all intents and purposes, that they’re just following the script, doing what daddy did. So the question becomes, can they put the past behind them and move forward? Or are they on a collision course with fate, one they have no control over?

First I lauded a script about two cancer-stricken teenagers earlier this year. Now I’m touting suicide entertainment. What’s wrong with me???

Not only was The Skeleton Twins good, but it succeeded where many other an indie film have failed. You see, when you don’t have a clear plot (like The Maze Runner – “Get out of the maze”), the story can easily get away from you. Without that big plot-centric protagonist goal, it’s not always clear where you’re supposed to take the story.

Well, in character-driven screenplays, like this one, the point shifts from achieving a goal to resolving relationships. That’s it. That is what’s going to drive the reader’s interest or not drive it. You create 3-5 unresolved relationships – characters with a big problem between them – and then you use your story to explore those problems. If the problems are interesting and you explore them in an interesting way, we’ll stick around to see what happens. Here are the four main relationships in The Skeleton Twins…

1) Maggie and Lance – she’s not sure if she wants to be with him.

2) Maggie and her scuba instructor – she’s trying to end the affair but can’t.

3) Milo and the old high school instructor – their relationship was cut off when they started it in high school. They have to figure out where it is now.

4) Milo and Maggie – they still have a few things from the past to resolve.

The other big thing you want to do with these non-plot-heavy indie movies is throw a lot of plot points at the story. Remember, we don’t have that big goal at the end to drive the film (Win the Hunger Games!), so you have to, sort of, distract us from that.

The Skeleton Twins does a great job of this. Maggie and Milo’s mom (whom they both hate) shows up unexpectedly. We find out Maggie’s hiding birth control. Maggie has an affair. We find out Milo had a relationship with his high school teacher. Lance finds out Maggie’s been on birth control this whole time they’ve been trying for a baby. Maggie ironically forgets to take the pill, discovers she’s late for that time of the month. I mean, for a tiny indie movie, there’s a lot of shit happening here. And that’s the way you have to do it with these indies.

I think lots of writers believe that because it’s an “indie” they need to show 20 minute shots of characters forlornly looking out at the sunrise set to an 8 minute Iron and Wine song set on repeat. There are a few of those shots in here, for sure. But the reason The Skeleton Twins succeeds where all these other indies fail is because it really packs a lot of plotting into its 90 page run time. There’s never something not happening.

On the non-screenwriting front, it was genius to cast comedians in these roles. This movie would’ve crumbled under the weight of two dramatic actors playing ultra-dramatic roles. The reason the film never falls too far into depression-ville is because of the dry offbeat humor Wiig and Hader keep slipping into their performances. Even Luke Wilson was great as the husband. Both funny and sympathetic.

This was a hell of good film. I should’ve saved my block of cheese for it.

THE MAZE RUNNER

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

SKELETON TWINS

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Small indie movies need a lot of PLOT POINTS. You need to keep throwing things at the characters or revealing secrets to keep the story moving and alive. Go too long without anything significant happening and your script gets pulled into that “indie boring void” that so often dooms an indie film. Don’t become another one of those indie films.

All this week, I’ve been putting one of YOUR dialogue scenes up against a pro’s. My job, and your job as readers of Scriptshadow, is to figure out why the dialogue in the pro scenes works better. The ultimate goal is to learn as much as we can about dialogue. It’s a tricky skill to master so hopefully these exercises can help demystify it. And now, for our last dialogue post of the week!

All I know about our first scene is that it’s an introduction to Charlie Lambda, who’s a major character, and Diane, who’s a minor character. It takes place in a bedroom after sex.

The room is cluttered with furniture and wrinkled clothing.

DIANE sprawls across the bed in her underwear, awake. Charlie LAMBDA stands at a dresser mirror, shirtless, buckling his jeans.

DIANE: Leaving so soon?

LAMBDA: Night waits for no one, my dear.

DIANE: Neither do I.

LAMBDA: You wanna leave? Suit yourself. I’ve got money to make.

DIANE: You got a night job?

LAMBDA: Best there is.

DIANE: You a pimp, Lambda?

LAMBDA: You know, most women try to figure people out before they sleep with them.

DIANE: I like mysteries. I like solving them, too.

Lambda grabs a shirt, buttons it up.

LAMBDA: You play cards, Diane?

DIANE: I play poker sometimes.

LAMBDA: You any good at it?

DIANE: I’ve got bad luck.

Lambda chuckles. From the dresser, he picks up a deck of cards. He shuffles them without looking, and they fly from hand to hand and around the deck like magic.

LAMBDA: Luck’s just a matter of stacking the odds in your favor.

DIANE: You still have to shuffle the deck. That’s luck.

LAMBDA: That’s what you think.

He brings the deck over to the bed and hands it to the woman, who sits up.

LAMBDA: Find the aces.

He walks back to the mirror, produces a comb, runs it through his hair. Diane sifts through the deck.

DIANE: So you’re a card shark.

LAMBDA: I’m a professional gambler.

DIANE: And you cheat.

LAMBDA: That’s what makes me a professional.

DIANE: I can’t find the aces.

Lambda goes to the bed, sits beside her, and pats her on the back.

DIANE: You’d take cards over an easy lay?

LAMBDA: It’s better than sex.

DIANE: Oh, really?

LAMBDA: You don’t understand. Playing cards ain’t a game. It’s a way of life. It’s zen. It’s jumping into a pool of sharks and seeing who’s got the coldest blood.

DIANE: And that’s you?

LAMBDA: Babe, Charlie Lambda’s the coolest guy around.

Diane tries to hand him the deck.

LAMBDA: Keep ’em. I’m going hunting.

He goes to the door and opens it.

LAMBDA: Go back to sleep, Diane.

DIANE: If you’re not here when I wake up, I’m gone.

LAMBDA: Wanna bet?

DIANE: Some odds you can’t sway.

Lambda smiles and closes the door behind him. Diane rolls over to go back to sleep– The four aces are stuck in her bra strap.

In this next scene from Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Joel is coming home on a train. Clementine enters the car and tries to find a place to sit. She eventually sits across the car, facing Joel. After awhile…

CLEMENTINE (calling over the rumble): Hi!

Joel looks over.

JOEL: I’m sorry?

CLEMENTINE: Why?

JOEL: Why what?

CLEMENTINE: Why are you sorry? I just said hi.

JOEL: No, I didn’t know if you were talking to me, so…

She looks around the empty car.

CLEMENTINE: Really?

JOEL (embarrassed) Well, I didn’t want to assume.

CLEMENTINE: Aw, c’mon, live dangerously. Take the leap and assume someone is talking to you in an otherwise empty car.

JOEL: Anyway. Sorry. Hi.

Clementine makes her way down the aisle toward Joel.

CLENTINE: It’s okay if I sit closer? So I don’t have to scream. Not that I don’t need to scream sometimes, believe me. (pause) But I don’t want to bug you if you’re trying to write or something.

JOEL: No, I mean, I don’t know. I can’t really think of much to say probably.

CLEMENTINE: Oh. So…

She hesitates in the middle of the car, looks back where she came from.

JOEL: I mean, it’s okay if you want to sit down here. I didn’t mean to—

CLEMENTINE: No, I don’t want to bother you if you’re trying to—

JOEL: It’s okay, really.

CLEMENTINE: Just, you know, to chat a little, maybe. I have a long trip ahead of me. (sits across aisle from Joel) How far are you going? On the train, I mean, of course.

JOEL: Rockville Center.

CLEMENTINE: Get out! Me too! What are the odds?

JOEL: The weirder part is I think actually I recognize you. I thought that earlier in the diner. That’s why I was looking at you. You work at Borders, right?

CLEMENTINE: Ucch, really? You’re kidding. God. Bizarre small world, huh? Yeah, that’s me: books slave there for, like, five years now.

JOEL: Really? Because—

CLEMENTINE: Jesus, is it five years? I gotta quit right now.

JOEL: — because I go there all the time. I don’t think I ever saw you before.

CLEMENTINE: Well, I’m there. I hide in the back as much as is humanly possible. You have a cell phone? I need to quit right this minute. I’ll call in dead.

JOEL: I don’t have one.

CLEMENTINE: I’ll go on the dole. Like my daddy before me.

JOEL: I noticed your hair. I guess it made an impression on me, that’s why I was pretty sure I recognized you.

CLEMENTINE: Ah, the hair. (studies a strand of hair) Blue, right? It’s called Blue Ruin. The color. Snappy name, huh?

JOEL: I like it.

CLEMENTINE: Blue ruin is cheap gin in case you were wondering.

JOEL: Yeah. Tom Waits says it in—

CLEMENTINE: Exactly. Tom Waits. Which son?

JOEL: I can’t remember.

CLEMENTINE: Anyway, this company makes a whole lie of colors with equally snappy names. Red Menace, Yellow Fever, Green Revolution. That’d be a job, coming up with those names. How do you get a job like that? That’s what I’ll do. Fuck the dole.

JOEL: I don’t really know how—

CLEMENTINE: Purple Haze, Pink Eraser.

JOEL: You think that could possibly be a full-time job? How many hair colors could there be?

CLEMENTINE (pissy): Someone’s got that job. (excited) Agent Orange! I came up with that one. Anyway, there are endless color possibilities and I’d be great at it.

JOEL: I’m sure you would.

CLEMENTINE: My writing career! Your hair written by Clementine Kruczynski. (thought) The Tom Waits album is Rain Dogs.

JOEL: You sure? That doesn’t sound –

CLEMENTINE: I think. Anyway, I’ve tried all their colors. More than once. I’m getting too old for this. But it keeps me from having to develop an actual personality. I apply my personality in a paste. You?

JOEL: Oh, I don’t think that’s the case.

CLEMENTNE: Well, you don’t know me, so… you don’t know, do you?

JOEL: Sorry. I was just trying to be nice.

CLEMENTINE: Yeah, I got it.

I chose these two scenes for a reason. In the first one, we’re looking at two strangers talking AFTER they’ve had sex. In the second, we’re looking at two strangers who’ve just met (before they’ve had sex).

Take note of the energy in each scene. In the first scene, the energy is relaxed, subdued, almost lazy. Which makes sense. They just banged. They’ve already reached the pinnacle of their coupling. Generally speaking, scenes where people are relaxed and happy are bad scenes. You’d rather seek out scenes where there’s tension, where there are problems that need to be addressed.

But in Eternal Sunshine, there’s still an entire world of possibility with these two characters because they haven’t consummated their relationship yet. As a result, their scene’s bursting with nervous energy. There’s excitement in the uncertainty of the moment. We feel tension. We feel hope. We want this to go right.

This is why, generally speaking, you don’t want to consummate the relationship until as deep into the script as possible. Once you do that, the dialogue between the characters loses something. The air will have seeped out of their “relationship balloon” so to speak.

But even if you took all this “consummation” talk away (I was told Diane wasn’t a major character, so maybe we shouldn’t hold her to that status), something’s still missing in that first scene. Let’s take a look at the first exchange. “Leaving so soon?” Diane asks. “Night waits for no one, my dear,” Lambda replies. “Night waits for no one, my dear?” That doesn’t sound like something real people say, does it?

That’s not necessarily a harbinger of doom, though. Some genres produce stylistic dialogue. Take the dialogue in “The Big Lebowski,” for example. Clearly, characters aren’t always talking the way real people talk in that film. The problem is, I’m not getting the sense that that’s what the writer intended here. I feel like this scene is supposed to be grounded. And in that case, lines like “Night waits for no one” come off as overly written, like the writer’s trying too hard.

This cuteness continues when the cards are introduced as a quasi-metaphor. Writing in metaphors (or analogies or clever explanations) is a very writerly thing to do. It gives the impression of depth and cleverness. And it allows you to talk about something by talking about something else. But if the only reason the analogy exists is to achieve this effect, it feels false. It reads as analogy for analogy’s sake.

Now I get the feeling that cards might play a larger role in this movie. If that’s the case, then the introduction of the cards isn’t as misguided. But I think the problem here is the same one we’ve encountered in most of the amateur entries this week. I don’t know what either of these characters wants in the scene! I don’t know if Lambda wants her out or if Diane wants to stay. There’s no clear objective, which means anything they say will appear as “babble” to the reader. It’s not that the dialogue is bad so much as we don’t know the point of it.

Looking at the Eternal Sunshine dialogue, there are two things that stick out. First, the dialogue is much more realistic. It’s short, it’s clipped, it ping-pongs back and forth uncertainly. But most importantly, it’s imperfect. It really feels like two people talking.

That’s a mistake we writers make often. We want our dialogue to be so beautiful, that we carve and mold each line into a perfect specimen of auditory delight. Put a bunch of these ultra-developed lines next to each other and the conversation starts feeling false. We don’t know why, but it does. It isn’t until we realize that no one would actually say any of these individual lines that we understand what’s wrong.

And we never see that problem in Eternal Sunshine. Words are flying by seemingly willy-nilly, with no rhyme or reason. It truly does feel like real life conversation.

Secondly, lots of writers get obsessed with balanced dialogue. Balanced dialogue is when there’s a perfect balance to the conversation. Each word, for the most part, is responded to with a word in kind. “Hey.” “Hiya.” “How’s it going?” “It’s going good. How bout you?” “Going good here.” And back and forth and back and forth in perfect balance.

Real dialogue is unbalanced. It’s often weighted to one side or the other, depending on the character or the situation. Read the bottom half of the Eternal Sunshine scene. Clementine is basically having a conversation with herself. Joel’s just there to hear it. That’s a big reason why this dialogue feels so authentic. Unbalanced dialogue is real life.

What about you? What stuck out to you about today’s scenes? The first one felt a little too “written” to me. But I can see some of you just as easily attacking the “rambling” quality of Eternal Sunshine. Share your thoughts!

What I learned: Balanced versus Unbalanced dialogue. There’s no such thing as perfectly balanced dialogue. Some characters are going to talk more than others. Some characters won’t always answer when asked something. No matter how many times you’ve rewritten your dialogue, it should always feel a little imperfect, a little unevenly weighted.