Will the adult diaper in Pale Blue Dot become the next Wilson the Volleyball?

Genre: Drama (based on a true story)

Premise: When a female astronaut returns home after her first trip into space, she finds her family life unwinding due to the unique pressures of her job.

About: Pale Blue Dot is a rarity – a DRAMA spec sale. The script started gaining buzz early in the year and then when Reese Witherspoon hopped on, was summarily snatched up. The writing team of Brian C. Brown and Elliot DiGuiseppi are coming off the buzz of landing on last year’s Black List with their biopic, “Uncle Shelby,” about cartoonist Shel Silverstein.

Writers: Brian C. Brown and Elliot DiGuiseppi

Details: 121 pages (undated)

Well shit. I didn’t know this was the crazy astronaut diaper story!

The way they presented this in the trades it was some gloomy drama about an astronaut trying to re-adjust to life on earth. But this is the story of that crazy astronaut chick who wore a diaper on a cross-country road trip to go murder the lover of her lover.

Which means we’ve got ourselves a screenplay!

Or do we?

At its heart, Pale Blue Dot is a drama – and the drama genre is a dying player in the movie business (unless we’re talking about biopics). I suppose this is kind of a biopic. It’s a true story, at least. But Pale Blue Dot exemplifies why dramas are on life-support. They just don’t generate the kind of heat that today’s busy audiences require to stop their lives and come to the theater.

Laura Pepper has achieved what very few people in history have achieved, especially women. She’s an astronaut. After coming home from her first mission, Laura should be on top of the world. And yet, minutes after touching down, all she can think about is when she’ll go back up again. This is despite having a wonderful loving husband and three amazing children.

While Laura struggles with these selfish feelings, she meets one of NASA’s hotshot astronauts, Mark Goodwin. The cocksure Goodwin is everything her husband isn’t. He’s carefree, he’s cool, he’s dangerous. And Laura needs danger right now – anything to fill the void of not being up there.

The two begin an affair almost immediately and things go from fun to serious. Or at least they do on Laura’s end. Laura can’t go a day without needing Mark. She needs to touch him, feel him, be next to him.

But the two are both married and there are unwritten protocols at NASA that astronauts can’t get involved with one another. For now, they’ll have to hide their love. But Mark assures Laura that all of this is temporary. They’ll figure out a way to be together soon.

And then Erin comes along. Erin is the hot new recruit who immediately catches Mark’s eye. Laura notices something between the two but convinces herself it’s nothing.

Unfortunately, it turns out Mark isn’t exactly the committed affair type after all. And when Laura learns the two are meeting up in another state to bang, she jumps in her car, determined to stop them. What follows has become one of the most infamous stories to ever make the news, and destroyed the lives of all three astronauts involved.

Let’s start with the obvious. We’ve got a drama spec sale here (a rarity). But before you drama writers start crafting your battle cry, keep in mind that this script is based on a true story. There’s no doubt that that played a huge role in the sale. I don’t think this gets past the first reader if it’s fiction.

And that’s because Pale Blue Dot is a lot more interesting as a discussion piece than it is a screenplay. It blasts off into territory most screenwriting teachers would tell you to avoid, the most obvious being our unlikable female protagonist. One of the first pieces of advice I heard when I started writing screenplays was: Male protagonists can cheat, female protagonists can’t.

This is not some sexist creed scratched up by male studio heads. It was formed after hundreds of test screenings over the years. When the audience – both male and female – saw the female main character cheat on her husband, they hated her, and hated the rest of the movie as a result.

Well, Pale Blue Dot takes this to a whole new level. Laura isn’t just cheating on her boyfriend or her husband. She’s got three kids! She’s choosing cheap sex over an entire family. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen this attempted in a movie before (with the female as the main character). It flies in the face of everything they’ve told us audiences will accept, so it’s a really bold move by both the writers and Reese.

But I think the script has far bigger problems to worry about. Cheating lead character or not, there isn’t a whole lot that happens in the movie.

I recently watched an interview with Francis Ford Coppola and he conceded that when he was editing The Godfather (a movie he initially didn’t want to make), he was afraid audiences would think it would be some long boring drama.

And this is the problem with drama. It doesn’t have those devices that help you easily keep an audience’s attention. Fear, thrills, action. The only thing you have to keep your audience watching is, well, drama. And in a world where the average person’s attention span has been cut in half since the year 2000, it’s become debatable whether that’s enough.

I used to hate when scripts started with a wild opening sequence only to jump back to “1 month earlier” or “1 year earlier.” I thought it was a cheap lazy device. But I’m realizing that with drama, it’s the only device to use if you want a shot at keeping your reader’s attention.

Pale Blue Dot starts with our heroine, Laura, wearing a wig, carrying a gun, and changing her soiled adult diaper right there in the middle of a gas station. It’s an intriguing series of events that definitely caught my interest. But then we cut to “1 year earlier” and we have to endure 100 pages of a woman feeling sorry for herself because earth isn’t as cool as space.

I have to admit though that if Brown and DiGuiseppi didn’t write it that way (with that opening scene), I never would’ve made it past page 20. No matter how bored I got, I had to see what happened with that diaper! So as annoying as those opening scenes are, I have to admit this one worked.

What didn’t work was Pale Blue Dot’s second act. It’s a woman feeling sorry for herself (a terrible trait in any character), wishing she was back in space, building a relationship with another astronaut. Even the affair felt restrained.

I mean, had Laura actually killed this woman, this would be Academy Award bait all the way. But when you don’t have a dead body, and your star scene is a soiled adult diaper, you need to start questioning whether you have enough meat for a screenplay.

On top of all of this, Pale Blue Dot struggles to explain how this love triangle is different from any other love triangle. I mean couldn’t this have just as easily been salespeople at a car dealership, waiters and waitresses at a restaurant, attorneys at a law firm? Having your astronaut characters say things like, the rest of the world “doesn’t understand us,” doesn’t make this an astronaut-specific story. And if it’s not astronaut-specific, you’re not exploiting half your hook (the other half, of course, being adult diapers).

With that said, the writers achieved what everyone who visits this site is trying to achieve – they got a major attachment and sold their script. So if there’s any advice to come out of this, I’d say it’s when writing a drama, write a part that a major actor/actress would want to play.

Laura’s astronaut-turned-diaper-wearing-scorned-lover character is, without a doubt, the kind of mind an actress would want to jump into. And so if there’s a saving grace to Pale Blue Dot, that would be it.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Dead bodies change everything. Seriously, if you have a drama you’re struggling with right now, figure out a way to get a dead body in there. I guarantee your script becomes 100 times more interesting. Look at one of the most famous dramas of all time, American Beauty. The movie starts with a dead body. Our main character’s. – Pale Blue Dot’s Achilles’ heal is that nobody got hurt. Nothing bad actually happened. And that hangs over the story throughout, leaving the reader with a distinct feeling of, “That’s it?”

Does Damon Lindelof’s infatuation with mystery boxes doom Tomorrowland?

Genre: Sci-fi/Adventure

Premise: A teenage girl finds a pin that allows her to visit a secret world of tomorrow.

About: Tomorrowland, directed by Brad Bird (The Incredibles), came out this weekend and finished the Memorial Holiday weekend with 40 million bucks, considered very low for what is, usually, one of the biggest movie-going weekends of the summer. Remember when 2015 was shaping up to be the biggest summer in movie history? Star Wars 7. Batman vs. Superman. Now we have films like Spy and Tomorrowland. What happened???

Writer: Damon Lindelof

Details: 130 minutes.

Pssst.

Hey.

Hey you.

Do me favor.

Come a little closer.

I have a secret I need to tell you. But you have to keep it between us.

Promise?

Pardon my paranoia. I just don’t want anybody to hear.

Are you ready?

I’ve never been a fan of Brad Bird.

I actually thought The Iron Giant was extremely overrated.

And The Incredibles?

I felt that every choice in that movie could be seen from a mile away.

I’ve always been kind of confused as to the geek love he’s been given. He made two movies that were amazing if you were ten. But other than that? He felt about as exciting as a wooden roller coaster.

Then I read that book about Pixar, “Imagination Inc.”, and the author went on and on about how in awe all of the biggest minds at Pixar were about Bird. And I thought, maybe I need to give this guy another chance.

On the other end of the spectrum, while the world seems to have given up on Damon Lindelof, I remain firmly in his corner. The guy literally came out of nowhere to write an entirely new third act and save the shit out of World War Z, preventing it from becoming one of very zombies it was depicting.

But regardless of who wrote this and who directed it, one thing was for certain: I was desperate for it to be good. I don’t know if you knew this, but Tomorrowland is one of only three major Hollywood releases this summer that are original ideas. A failure with this film was one more reason for studios to never choose original scripts again.

So when I sat down, I sat down hoping for a movie miracle. Did I get it?

Not exactly.

The story follows teenager Casey, a genius who uses her unique skills to take down power plants that are harming the environment or something.

After going to jail for said plant attackage, Casey receives a strange pin that, when touched, transports her to a futuristic city.

The problem is that the pin has a battery life worse than an Apple laptop and eventually runs out of juice, forcing her to run to the internet to find out how to power it up again. This leads her on a strange adventure cross-country where she eventually crosses paths with Athena, a 12 year-old girl who’s actually a robot FROM this futuristic city (which we’ve now dubbed Tomorrowland).

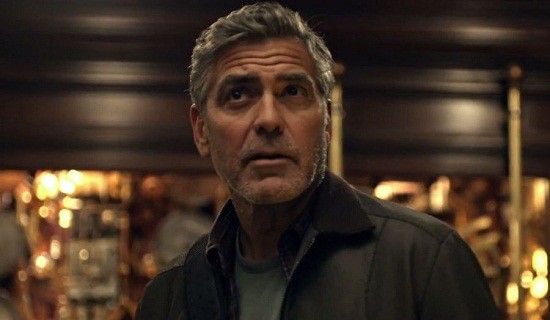

Athena takes Casey to Frank, a cranky old former inventor who, like Casey, visited Tomorrowland when he was young, and actually fell in love with Athena. The three of them have been assembled to save humanity, which, according to calculations, is going the way of the dodo birdy in 60 days. Only through the secrets of Tomorrowland will they be able to stop the apocalypse.

Oh man.

Where do I begin here?

I don’t know if I’d call Tomorrowland “bad.” But holy shit is it flawed.

I’ll start off with the strange decision to make this a tri-protagonist story. If you come to the site often, you know how I feel about this. Any scenario where it’s unclear who your protagonist is, is a “playing with fire” scenario. I’m not saying you’ll for sure get burned, but it’s a bit like heading to Egypt without sunscreen. You’re probably going to regret it.

Lindelof makes things really hard on himself as he creates a storyline that’s way more complicated than it needs to be, as Frank, Casey, and Athena take a good 70 minutes just to get to the point where they’re on their mission.

This essentially makes the 70-page mark the end of the first act (the beginning of the second act is well known as the moment our main character heads out on their journey).

Now Lindelof would probably argue that Casey goes off on HER mission around the traditional 25-minute First Act marker. But since that mission is really just the beginning of setting up two more characters (completing our tri-protagonist trio), we don’t get to the TRUE beginning of the journey until we meet Frank and he prepares the trip to Tomorrowland.

If you’re doubting my page 70 First Act turn assessment, I’d ask you how you were feeling 45 minutes into the movie. Bored right? Like we were spinning our wheels? Like we were moving from scene to scene, but nothing was really happening.

THIS IS BECAUSE we were still in the first act. We hadn’t officially gone on our journey yet.

Now this is where Lindelof is going to get some heat and he probably should. One of the big knocks on Lindelof is his and JJ’s “mystery box.” Critics say that he and Abrams are more interested in posing questions than offering answers, creating a sort of cinematic blue-ball effect.

This has caused some online to announce the death of the mystery box, which is the most absurd thing I’ve ever heard in my screenwriting life. It’s not mystery boxes that people don’t like. It’s badly executed mystery boxes.

It’s like that old screenwriting rule: never write a dialogue scene on the phone. Always have your characters talk in person instead. Well, yeah, that’s sort of true. But what audiences are really rebelling against are BADLY EXECUTED phone-call scenes. I don’t know anyone who had a problem with the Rod Tidwell phone scene in Jerry Maguire.

So anyway, I think Lindelof believed that his mystery boxes would keep us occupied inside those first 70 pages so that we wouldn’t notice he was writing the longest First Act in history.

There was only one problem. All the mystery boxes revolved around Tomorrowland, and we had already seen Tomorrowland twice. Once at the beginning with Frank and then once in the First Act with Casey. How do you create mystery around something we’re already familiar with?

There’s the whole “mysterious countdown” til earth blows up thing. But there’s a countdown in every Hollywood movie. You’re not going to keep us around with a standard countdown.

Your star mystery box was Tomorrowland and you blew that by throwing it into the very first scene. It was a baffling choice to say the least.

And as if to make things worse, when we finally get to Tomorrowland at the end, it’s a toned down lame version of Tomorrowland – the empty “unfun” version. So not only did you obliterate any curiosity about the place but when we finally see it, it doesn’t live up to our expectations.

The film’s message of “We can build a better tomorrow if we try” was given SO FREAKING MUCH ATTENTION that it appears Lindelof and Bird – two story-guys through and through – didn’t notice these flaws. Which is too bad. Because they really destroyed Tomorrowland. And made me happy I’m still back in Today.

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Tomorrowland is a great example of what can happen when you oversell your theme. When you’re repeating your message every two pages (“We’re ruining the planet!”), and characters are stopping the script for long monologues about the message of the film, the audience starts feeling manipulated. A great way to avoid this while still pushing your theme, is to move away from stating theme, and look for ways to show theme. So say your theme is about pushing forward in the face of adversity. You don’t want one of your characters to say, “We need to push forward in the face of adversity guys!” Which is essentially the tactic that Tomorrowland employs. Instead, show a bunch of situations where characters are faced with adversity. Show some stand up to it and the power they achieve through doing so. Then show others fail to stand up, along with the negative consequences their actions bring. This is much more effective.

A former Amateur Friday entrant comes back for more. And Carson proclaims that rules have rules. Have both these men gone insane?

NOTE: Scriptshadow will not be posting on Monday, which is Memorial Day here in the states, an entire holiday dedicated to improving our memory. So use that extra day to work on your Scriptshadow 250 Contest Entry!!!

Genre: Dark Comedy

Premise (from writer): In the final days of a yearlong deadline to either improve his life or end it, a sheltered mama’s boy, with nowhere else to turn, appoints a would-be criminal as his new life coach.

Why You Should Read (from writer): March 9, 2012, a day dubbed as “the Jai Brandon experiment,” Carson reviewed a script of mine titled, “The Telemarketer.” — When I originally wrote that screenplay, I thought “entertainment value” outweighed plot, structure, “rules,” or anything else you want to throw out there. I was a screenwriter with all of 18 months on the job and thought I had this craft figured out. I was confident in my ability to entertain, though I never made claims that The Telemarketer was “better than every script sale out there,” or “better than some of the classics that have graced our movie theaters for years.” I wasn’t ever that clueless. However, I did think the story could hold my readers’ interest throughout.

Boy was I wrong.

The most memorable feedback, to me, wasn’t even about the script. What stuck with me the most were comments along the lines of “I put this down at page XX.” Or “I bailed after page XX.” It sucked to fail at the very thing I thought I could accomplish. — Since that time, I’ve read tons of screenplays and penned another unconventional script that never went anywhere. Enough is enough. I wanted to prove to myself that I had the discipline to follow the rules. As a struggling actor, I also wanted to create a story that would be relatively easy to produce, with me as one of the leads. I decided to use the central idea behind The Telemarketer – as well as a couple of scenes from that script – and write a dark comedy called Three or Out. Hopefully this time I succeed in accomplishing what I failed to do earlier: hold my readers’ interest with a compelling and conventionally structured screenplay.

Writer: Jai Brandon

Details: 114 pages

It’s been a long time since I read Jai Brandon’s original Amateur Friday script, and I went back and forth on whether to reacquaint myself with that review. Ultimately I decided I wanted no baggage going into this one and to judge it on its merits alone.

Also, it seems that Jai has become quite humbled by that experience and I think that’s a good thing. As a screenwriter, you don’t want to ever get too high on yourself. In fact, you almost want to be the opposite. The more skeptical you are of your abilities, the higher you’ll set the bar for yourself.

This review is a bit long, so I don’t want to waste any more time prepping it. Let’s dig in.

Arlen, who’s barreling closer to the big 3-0, isn’t exactly kicking life’s ass. He still lives with his mom, who’s a major bitch and driving him crazy. He has a sucky telemarketer job that barely pays anything. And he doesn’t get no love from the ladies.

A year ago, Arlen told himself that if he didn’t fix these three things within a year, he would kill himself. Now, with only a week left on that deadline, it’s not looking good for Team Life.

However, after a pesky customer named Xavier gets pissed at Arlen for not offering him a job (not sure why you’d expect someone you don’t know to find you a job) the two run into each other at a convenience store, and Xavier takes the opportunity to shake Arlen down for money.

Arlen tells Xavier that he can have his money, but only if Xavier helps him achieve his three goals by the end of the week. The unlikely partners then set about getting Arlen’s life back on track, and in the process, saving it.

What good are my articles if we never reference them? Hence, I’m going to take today’s script and put it through yesterday’s Seven Questions ringer. Buyer beware, this is not the nice sweet cuddly version of “Does your script meet our requirements?” This is the mean Hollywood producer asshole version of “Don’t waste my time.” In other words, real life! :)

1) Is your idea high concept?

This is a movie about a guy who’s basically trying to get a new job. The suicide angle gives it a slight edge, but not enough to call this high concept.

2) Are you writing in one of the six marketable genres (horror, thriller, sci-fi, comedy, action, adventure)?

No. We’re going Dark Comedy here, which is a hard sell in the marketplace, although occasionally celebrated on the Black List. Still, this is two strikes.

3) Is your idea marketable?

I can’t think of any successful movies like this really so I’ll unfortunately have to say no.

4) Do you have a fascinating or extremely strong main character?

Our main character is a depressed guy who wants to be a little happier. Not exactly the kind of role actors are desperate to play. Xavier and the mother have a little more meat to them, but in a screenplay, we’re looking for GREAT MEMORABLE characters, not just “okay” ones.

5) Does it have a unique angle?

Since we aren’t sure what kind of movie this is (there isn’t really a “suicide” sub-genre) there’s no opportunity to create a new angle.

6) Is your script packed with conflict?

There is some conflict here. There’s conflict between Arlen and Xavier, Arlen and his mom, Arlen and himself. So we can say yes to this one.

7) Does your idea contain irony?

The saving grace for low-concept is irony. If you can add irony to your premise, you can really improve your script’s appeal. So this is about a guy who wants to commit suicide or make his life better. There’s unfortunately nothing ironic about that. Although this is a bit on the nose, the idea would be more ironic if our main character, who was suicidal, worked as an operator at a Suicide Prevention Hotline. Listening to Arlen provide a boatload of people with great reasons to stay alive while he was secretly planning to kill himself would’ve been a clever way to draw us into the story.

Which gives “Three and Out” a score of “1” on the 7-point scale. Does this mean the script is hopeless? No, American Beauty would’ve scored low on this test as well. But what it does mean is that the script has to be a thousand times better than the scripts that DO meet these requirements, since those scripts are going to be a thousand times easier to sell. The lower the score, the more amazing the writing has to be.

So was the writing amazing? While I think Jai’s writing has improved, you have to remember that following the rules comes with its own set of rules. And one of those rules is that your story must feel seamless, despite being structured.

Three or Out ran into trouble almost immediately due to its forced setup. How many times throughout history has a telemarketer ran into someone he was talking to on the phone just ten minutes earlier? That’s hard to buy into.

I understand what Jai was trying to do. He had Xavier point out, due to the “private number” on his caller ID, that Arlen must live locally, allowing us to buy into their later meeting. But the fact that Xavier had to bring that up is exactly what brought MORE attention to the artificiality of this conceit, not less.

The second I’m stopping to think about how weird or coincidental things are is the second the script enters Trouble Territory.

One of the skills professional screenwriters have is that they’ve learned to make their plotting SEAMLESS. You never see the gears grinding underneath their script. By that I mean, you don’t see the writer’s attempt at covering up the hugely coincidental moment that two characters run into each other. Professionals either hide the cover-up better, or come up with a situation that isn’t difficult to buy into in the first place.

For example, why not take the telemarketer stuff out altogether? With Arlen being suicidal, let’s put him into an even more desperate state. He’s collecting welfare. And he’s barely able to support his mom with the money, which is why he wants to go out there and get a job in the first place.

Then, have him meet Xavier when they’re both at the store and Xavier tries to rob it. There doesn’t have to be this big weird artificial coincidence that facilitates their meet-up. It can and should be simple.

Another problem with the setup is that it didn’t make a lot of sense. What was it, specifically, about Xavier that Arlen needed to achieve his goal? He needed Xavier to help him visit potential apartments? Really? He couldn’t have done that by himself??

It seems like Jai is following the “rules” approach too literally. He’s so set on having this conflict-fueled pair drive his story that he hasn’t really considered why our main character would need this criminal to help him in the first place. Arlen can barely scrape together 500 a month for rent, yet he’s paying Xavier four grand to act as a second opinion??

I could get into some other things but truth be told, the forced set-up was the moment I sub-consciously withdrew from the screenplay. I’ve been down this road too many times to know that if you can’t nail a seamless setup, then more issues are coming.

And that’s not to say there aren’t some good things here. This script is very easy to read. The writing is sparse and keeps the eyes moving down the page. I like that Arlen has a goal here and a ticking time bomb, even if it’s self-enforced. The dialogue is snappy. I liked the complicated relationship between Arlen and his mom.

But I think this comes down to me not being excited enough about this idea. If I’m Mr. Producer and this hits my desk, I’m having a tough time seeing how I could sell this movie. There’s no real hook, unless you argue that suicide in a week is a hook. And I’d probably fight you on that. And the stakes are kinda low since they’re self-enforced. If Arlen doesn’t meet his requirements, he doesn’t HAVE to die. He can just change his mind. So we never really feel that he’s in danger.

So I think Jai just needs to keep working on it. When you come over to this side (the rules side), there’s two halves to the process. The first is writing a script that follows the rules. And the second is writing a script that follows the rules but integrates them seamlessly, so that the audience isn’t aware of them. You’ve achieved part 1, but not yet part 2.

Get back in there and figure out part 2. I’ll be rooting for you.

Happy Memorial Day to everyone. I’ll see you Tuesday!

Script link: Three or Out

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This isn’t so much a “What I Learned” as an exercise. I want each one of you to try and come up with the best logline about suicide you can that uses IRONY. Understanding irony is the key to writing an indie movie that people will actually care about. Good luck!

ALERT ALERT!!! The SCRIPTSHADOW NEWSLETTER has been sent! Check your SPAM and PROMOTIONS folders if you did not receive the newsletter in your mailbox. You can add my e-mail to your ADDRESS LIST to make sure future newsletters go straight to your inbox. If you still can’t find the newsletter, e-mail me with the subject matter – NEWSLETTER. It’s a BIG one, with a review of what many consider to be one of the best scripts of the past five years. Sign up for the newsletter here.

So it happened again.

What’s that? You don’t know what I’m talking about?

Oh.

I had another meet-up with a writer.

Which resulted in another, “What the HELL are you thinking?????”

A sweet well-intentioned guy. Very nice.

But then it happened. He pitched me. Told me what he was working on.

I listened. I tried to be patient. But before I knew it, I was shaking my head. I asked him if he read my site. Because he said he was inspired by it. But if you’re inspired by my site, why are you doing the exact opposite of everything I talk about?

That may seem like a harsh reaction but I used to stay quiet in these situations. Nod my head and smile. But what good does that do anyone? Is it better for me to let this gentleman waste the next six months of his life or tell him right then and there that his ideas…well… suck.

What was the problem with this young gentleman’s ideas? None of them were movies! There wasn’t a single cinematic idea in the bunch. I’m not going to expose those ideas here for the world to laugh at. But let’s just say they were the equivalent of a man struggling through a job he didn’t like. Very basic, very “un movie like” premises.

Hearing him talk about these ideas, you could feel his passion. But passion without a good idea is about as useful as a slurpee without a cup. It’s going to spill all over your clothes, leave a stain, and result in a very angry Indian man yelling at you.

Okay, so it’s not exactly like a slurpee without a cup but the point is, this is amateur mistake numero uno. The thing that keeps 90% of aspiring screenwriters on the wrong side of the Hollywood wall. Their ideas are BORING! They don’t promise us anything exciting.

How does the saying go? A cat sitting on a blanket isn’t an idea. A cat sitting on a dog’s blanket is.

And there are a lot of things that go into it but basically you want to give the audience an idea that promises a lot of conflict. I mean look at the setup for Fury Road. A woman steals the most powerful man in the region’s five wives and tries to run away. We can see how that’s going to end up in a lot of conflict, a lot of problems, a lot of “shit going wrong.”

The reason I’m babbling on about this is because I’m tired of seeing writers waste their time on boring freaking ideas that will never go anywhere. I read them all the time in the Amateur Offerings’ submissions and I think, “What are you thinking??? How could you possibly think anyone would want to see this movie?”

For awhile I thought these were just hopeless writers who didn’t have the talent to come up with a good idea. But then I started thinking, maybe no one’s sat down and taught these people the difference between a good idea and a bad one.

So I came up with 7 questions to help these writers determine the value of their idea. If they can say yes to at least four of these questions, they probably have a story worth telling. Any less and they may want to go on to the next idea.

Now I’ve ranked these in order of importance. So the top questions are weighted higher than the bottom ones. In other words, it’s more important that you answer yes to the first few questions.

A couple of things to remember. The game changes if you’re going to direct your script yourself. That’s because when you direct, you give yourself another opportunity to differentiate your product. So if your script seems mundane on the page, but you plan on shooting it in a really unique or weird way, that still allows you to stand out. Like Gregory Go Boom. That script probably looked mundane on the page, but the director gave it a truly fresh feel on the screen.

Also, don’t try and defend your idea by putting it up against similar ideas that were a) book adaptations or b) director-driven projects. As a spec screenwriter, you will never get the benefit of the doubt a New York Times best seller does, nor will producers care when you plead with them, “I know not a lot happens but it’s going to be like a David Lynch film.” Since you’re the unknown spec writer, you have to be bigger and flashier to get noticed. So here are the seven questions you’ll hopefully answer “yes” to. Good luck!

1) Is your idea high concept?

I’d say that this is probably the most helpful thing you can do to get your script noticed. I read ARES, Michael Starbury’s script about a special division created to recover the extraordinary and supernatural. Truth be told, it wasn’t very good. But the idea was so big, so “you could totally see this as a movie,” that it sold for mid six figures. High concept is not synonymous with big budget either. A high concept could be a therapist who takes on a child patient who sees ghosts (The Sixth Sense). Or a couple who runs into their doppelgangers on their vacation (The One I Love).

2) Are you writing in one of the six marketable genres (horror, thriller, sci-fi, comedy, action, adventure)?

These are the genres that sell best on the spec market. Dramas don’t do well here. Westerns. Period pieces. Coming-of-age stories. If you’re not writing in one of these six, you should probably be worried about your spec’s chances.

3) Is your idea marketable?

This would appear to be the same question as number two, since the reason those genres are celebrated is because they’re marketable, but there are plenty of non-genre movies that can still be marketed. One of the ways you can figure this out is to find three movies (within the last decade) similar to yours that have done well at the box office (relative to their costs). The biopic is a good example of this right now. Studios have proven they can market these movies and people will show up.

4) Do you have a fascinating or extremely strong main character?

Actor bait can work as a sort of Hail Mary for smaller ideas. Think a meaty juicy role where an actor gets to do a lot of stuff. It could be anything from being a schizophrenic (A Beautiful Mind) to being bitter and having scars on your face (Cake, Vanilla Sky).

5) Does it have a unique angle?

We just talked about this the other day. Once you choose your idea, try to figure out what your unique angle is going to be. If you don’t have a unique angle, it’s likely your script is going to feel just like everything that came before it. Take one of the unexpected hits from a couple of years ago, “Now You See Me.” The writers decided to write a heist film. But everyone writes heist films. What was different about theirs? Well, they made the heisters magicians. That’s an angle we haven’t seen before.

6) Is your script thick with conflict?

A premise that promises a lot of head-butting between characters, a lot of tension, a lot of sides pulling at one another, a lot of uncomfortable interactions, is an idea that’ll likely make a good screenplay. A perfect example is Gone Girl. A woman disappears and we follow the husband, who everyone suspects killed her. Every situation this man steps into is going to result in some kind of conflict. Contrast that with, say, a movie about a man who’s grieving the loss of his life. I guess there’s some inner conflict in that idea, but it’s minimal, and we’ll grow tired of it quickly, meaning the idea is weak. A man who grieves the loss of his wife, only to find out she used to work for the CIA, and now people who were after her are now after him? Okay, you might have an idea there.

7) Does your idea contain irony?

If you’re writing what many would consider to be an “independent” movie, I consider an ironic premise almost essential. It’s really your last ditch effort to make your tiny movie stand out. A king who can’t speak must give the most important speech in history (The King’s Speech). When an older man meets a minor online, it turns out to be the minor who’s the predator (Hard Candy).

Don’t worry if you don’t get an affirmative on every one of these questions. That’s unlikely. But as long as you get more yes’s than no’s, you should be in good shape. Also, there’s a final component to all of this, and that’s your own creativity, your own voice. You have to add those creative flourishes and ideas that only you can bring to the table. For example, I could write a movie about a group of teenagers stuck in a town full of zombies that would get yes’s to most of these questions. But if I’m not bringing some creativity to the story, it’ll still be a dud. Nobody wants to be a dud. Be a stud. And never ever roll in mud.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A home invasion crew targets the richest family in town, only to get a lot more than they bargained for.

About: This script was just purchased a couple of months ago. Eric Bress actually sold ANOTHER script, American Drifter, a couple of weeks later. Bress is best known as the co-writer and co-director of The Butterfly Effect, a film that he’s remaking as we speak. Let’s all pray that Ashton Kutcher isn’t in it.

Writer: Eric Bress

Details: 85 pages

They say that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.

On Monday, I officially changed the definition of insanity to just: George Miller, after seeing how fucked up Fury Road was.

Well, I’m about to change the definition again. I’m going to give half of that definition to Eric Bress. Holy SHIT is this guy dark. I mean…. Lol… I’m sitting here still shaking my head. And I finished this script 20 minutes ago.

This is, like, disturbed shit on a whole other level.

But the great thing about art? Is that you can be disturbed as well as admired. And I admire the hell out of this screenplay. I mean, this was supposed to be a home invasion movie. How crazy could it get?

Here’s an answer for you: VERY FUCKING CRAZY.

The Schottenfelds are rich as hell. We notice that by their 20 acre property and huge mansion. We have the wiry, maybe even wimpy, father, David. The trophy wife who’s secretly a badass in Barbara. 17 year-old emo, Meredith. And the jock of the family, 12 year-old Lance.

Oh, and there’s one more family member. 18 year-old loner, James. Now, the way this script is written, we start with a home invasion and then jump back in time at various points to get to know the characters before the event.

And what we learn about James is that he’d purchased a Contra-sized arsenal of weapons and was planning on pulling off the biggest school shooting in history. Luckily for those students, his parents found out about it, and were about to send him off to a special program to make him better.

But James hasn’t left yet. And thank God for that.

On a seemingly normal evening, the family is getting ready to do what families do, when eight men barge into the house and demand, well, just about every cent this family has, including every bank account they’ve stashed money in across the world.

The group is led by one nasty motherfucker in Burke. Burke isn’t afraid to feel up Meridith, hang Lance over a 30 foot balcony, light David on fire, and beat the shit out of Barbara. This is just not a good dude in any sense of the word.

The problem is, while Burke seems to know way more than he should about this home, he doesn’t know that James hasn’t left yet. And that James has a stockade of weapons that could take down ISIS. What follows is the reversal of all reversals. Burke and his crew go from the hunters… to the hunted.

There is so much good about this script, I don’t know where to start. First of all, it’s not for the squeamish. There is some hardcore violence in here so if that’s not your thing, the charms of this screenplay will likely not work on you.

But if you were delighted by scripts like Fatties, then read on!

Let’s start with ANGLES. Remember that there are about 75 movie types out there. By that I mean, sub-genres within the main genres. So we have the teenage romantic comedy, the alien invasion movie, the body switch movie, the serial killer procedural, the trapped in a box with monsters flick, the buddy comedy, the revenge flick, the coming-of-age movie, etc., etc.

These are all proven movie types so they’re used over and over again. What your job is when you write one of these films is to find an ANGLE that makes them different. So take teenage romantic comedies (Clueless, The Breakfast Club, Mean Girls). If you’re going to write a teenage romantic comedy, you need to find a new angle, because if you give us a generic teenage rom-com or one that doesn’t offer anything new (example: the Freddie Prinze Jr. masterpiece, “Down To You”), we won’t feel any need to see it.

A recent example of Hollywood finding a new angle for this type of movie is The Fault In Our Stars. A teenage romantic comedy about cancer patients. Hadn’t been done before. It was risky as shit, but usually the angle you pick will be risky. In order to find a new angle, you’ll need to do something that’s never been done before. Which is, by definition, risky.

So here we have the home invasion movie. We’ve seen this film before with Panic Room and Firewall and The Purge. So what’s the new angle you’re going to bring to it? In American Hostage, it’s that the teenage son is a psychopathic murderer who’s a thousand times worse than any of the invaders. And instead of them hunting him, he hunts them. That’s the angle that makes this script different.

Now if that was all there was, it wouldn’t be enough. You can’t JUST be different. You have to execute. And boy does Bress execute. I usually know I’m in good hands when I read something in a script that I’ve never read before. That tells me the writer is creative and that he’s TRYING. That last part sounds like it should be a given. But 90% of writers out there aren’t trying hard enough to make their scripts great. So it’s a big deal when I notice this.

What’s the moment I’d never seen before?

James drives the invaders’ van up to the house with the head of one of the men he’s killed planted on top of the swaying antennae. Before he killed this poor guy, he made him record a message in his iphone to the other invaders (telling them to leave). So when the invaders come outside, the head bobs back and forth, the message playing from the iphone, making it sound like the severed head is really talking. It’s the creepiest fucking image I’ve read all year.

But what about the story, Carson! I mean is this just a series of gross gimmicks? No! This script is really good. And it works because we know that James is out there. And that he’s killing these guys one by one. So we’re driven to keep reading to see where he’s going to strike next. And since Bress did such a great job making us hate these guys (beating up the mom, groping the daughter, lighting the dad on fire), we can’t wait for that next attack.

Also, I really liked the jump-back structure here, with the invasion occasionally interrupted to go back a week and meet the characters in their everyday environments. This allowed us to get to know the characters on a deeper level so that we gave a shit when they were stabbed or hit or… lit on fire.

Usually in a script that jumps into the action right away, you don’t get that, so we don’t really know the people we’re supposed to care for. Bress found a way around that problem. And he didn’t do it with super-long flashbacks or anything. Each jump-back was one scene. Very tight and easy to digest.

The script also made me feel something I’ve never felt before. We learn, early on, that James planned on shooting up a school, one of the most horrific acts you can imagine. So the fact that you’re rooting for this guy gives you this complicated uneasy feeling inside. You know you shouldn’t love him. And yet you do. You can’t wait for him to dole out more pain to these assholes.

It’s pretty rare that a script will make you feel multiple things at once. So when you find one that does, you raise your cap. And then put it on a car antennae.

The only downside to this script is that it’s so violent that it won’t be for everyone. And that sucks, because there are people who won’t be able to appreciate how well-written American Hostage is. And it’s really well-written. This is a great example of how to write a memorable contained thriller.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Do yourself a favor and consider an UNEXPECTED HERO for your screenplay. Everyone knows Vin Diesel’s going to beat ass, that The Rock is going to take names, that Jason Statham is going to kick your teeth in. These characters are all very on-the-nose. So what if, instead, you went with the most unexpected choice for the ass-kicker (or hero) in your movie? A mentally unstable 18 year-old who was planning to shoot up a school. That’s about as unexpected as it gets.