Scriptshadow 250 Contest Deadline – 85 days left!

Genre: Biopic

Premise: The story of Joy Mangano, the creator of the Miracle Mop, one of the most successful products in history.

About: The winning combo of David O’Russell and Jennifer Lawrence is back. And talk about a strange writing twist as Annie Mumolo, best known for co-writing the hit comedy, Bridesmaids, with Kristin Wiig, has taken on scripting duties. Joy will be hitting theaters later in the year, smack dab in the middle of Oscar season, and will secure Lawrence her second Oscar (yes, I’m calling it right now – this is a foregone conclusion).

Writer: Annie Mumolo

Details: 136 pages (First Studio Draft – May 17, 2013)

Chant it with me: Bi-o-pics! Bi-o-pics! Bi-o-pics!

Are biopics becoming the new indie superhero movie? Everywhere you look, here comes another one. I’m sure it’s only a matter of time before these indie studios find a way to create “universes” out of biopics. Like maybe Nikola Tesla can appear in a movie about River Phoenix. Or Erin Brokovich can cameo in The Imitation Game 2. Can somebody say “bank?”

In all seriousness, I’m shocked that no one’s made a story about Joy Mangano before. If everything I just read is true, this is one of the most amazing true stories ever. I’d go so far as to say if you want to enjoy this script (or the film), don’t read this review or research Joy. The joy (no pun intended) of this script comes from experiencing all the little twists and turns in Joy’s life as she pursues her dream.

However, seeing as this is a textbook example of how to write a great biopic, I would encourage anyone writing one themselves to seek the script out and study it. I’ll talk about why this is such a great script in a second. But first, here’s a quick breakdown of the story.

When Joy marries the perfect man in Tony Mangano, the Long Island native is floating on Cloud 9. After having three kids, you couldn’t draw up a better dream life than if you manufactured white picket fences for a living. But all that comes crashing down when Joy finds out Tony’s been cheating on her.

Most women would’ve swallowed their pride and kept their husbands after this news. But Joy is not “most women.” She divorces Tony and attempts to raise her three kids on her own. That proves tough, but luckily, Joy’s been working on an idea she’s come up with. A mop that magically picks up everything when you use it, the water AND the gunk.

Soon she’s selling these mops outside K-Marts before finally getting a shot to do a run on HSN. After some doofus screws up the pitch on the mop’s first run, Joy gets a shot to personally pitch the product. The result is shocking, with her selling out every single mop she’s produced.

With the help of her father, who secures a manufacturing deal in California, Joy soon has a fledging business. But when the manufacturing company suddenly raises her prices, she suspects something foul is afoot. Being Joy Magano, she personally flies there to find out what’s going on. What she finds out is shocking not just because she realizes everything about her business is a sham, but that it was her own family that did it to her.

This script is a testament to the power of the ACTIVE MAIN CHARACTER. We talk about that all the time. But you really see it in action here. An active main character GOES AFTER THINGS. And we like people who go after things.

For example, when Joy’s product gets picked up by HSN, they have some actor who doesn’t know the product demonstrate it. And he does it all wrong. Naturally, the mop doesn’t sell. So what does Joy do? She personally goes to the HSN headquarters and demands to speak to the president. That’s what I mean by ACTIVE.

Again, later, when Joy can’t get anyone from the manufacturing company on the phone as she’s trying to figure out why they’ve raised her prices, she FLIES TO CALIFORNIA to confront them. Again, that’s an ACTIVE character. Audiences LOVE watching characters do this. And it makes stories so much more exciting. Wouldn’t you rather watch someone who’s passionately purusing something than someone who’s sitting around letting life pass them by?

I suspect a lot will be made of how powerful a role this is for a woman, and they’re right. There should be more roles like this for women. But again, this kind of role needs to be written for EVERYBODY. There aren’t enough roles written with characters who are this active. That’s the main reason “Joy” works.

Speaking of the active stuff, there’s another great screenwriting tip buried in the “go to California” scene. I’m going to guess that, in real life, Joy didn’t go to California. I think she probably made a lot of phone calls and figured out they were screwing her over. However, as a storytelling device, phone calls are boring.

So instead, Mumolo had Joy go to California, and we get a much better scene as a result. While Joy is questioning the people at the company, her friend is outside and sees men sneaking Joy’s mop molds into a truck. Her and Joy then follow the truck, and eventually get an officer to stop it, and confront the man driving. This is way way way more entertaining than any scene you could’ve gotten on a phone call.

There’s other things about this script that make it stand out as well. Take Tony, the cheating husband. What are most writers going to do with this character? They’re going to vilify him, right? It’s the obvious thing to do so it must be the right choice. Well, instead, after their initial break-up, Tony actually becomes a supporter of Joy’s. He wants her to succeed.

This minor unexpected touch made the movie feel more like reality. Because if every character follows the typical movie blueprint, people become aware that they’re watching a movie. When characters act unexpectedly – outside of stereotypes or clichés – it tricks the viewer into thinking they’re watching real life.

And actually, I loved who the villain ended up being (major spoilers ahead). The villain was the father. He ended up deceiving Joy and stealing her patent in order to make a buck. And when you think about what you want out of a villain – which is to infuse frustration and anger into the audience – there’s really no better person to do that than family.

I mean, who the hell cares if Ultron screwed you over. You don’t even know the guy. But your own father?? The person who raised you?? The person who you trusted more than anything?? When it’s THAT person who deceived you, it’s going to hit on a 100x deeper level than any villain Marvel can come up with.

With that being said, the father is the only element here that needs further development. He only becomes a major player late in the movie. Before that, we saw bits and pieces of him as well as hearing about him peripherally (he divorced Joy’s mom so she always complained about him). We needed to see a couple of more scenes with him and Joy early so his deception at the end hits harder.

But other than that, this script is the bee’s kneecaps. And I have to give props to both Russell and Mumolo. Russell gets a lot of heat for his activities on set. But there isn’t a director out there right now who understands storytelling better than him. And I’m not going to lie. I totally pegged Annie Mumolo as a lightweight after Bridesmaids, someone who benefitted greatly from a friendship with Kristin Wiig. But this script proves she’s the real deal, and might even win her an Oscar.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive (Top 25!)

[ ] genius

What I learned: Montages are often boring and skipped over by readers. People aren’t interested in reading through a bunch of random shots. So I love what Mumolo does here. She NAMES her montages. This instantly gives the montage a theme and therefore strips away their randomness. So for example, on page 31 we get the “Joy Without Tony” montage, to signify her new daily routine after her divorce. Then later the “7000 Mops” montage, where she must somehow produce 7000 mops. It’s a small thing, but for someone who hates montages, I found it clever.

Genre: TV Pilot – Drama

Premise: Right now there is an oil boom going on in America, one that will change everything about the world, as well as everything about the town it inhabits.

About: We’ve got writers from two different worlds colliding on this one. Josh Pate has been writing for television for 20 years. His credits include shows like Falling Skies and Legends. Rodes Fishburne, on the other hand, is a novelist (Going to See The Elephant – about a man who moves to San Francisco) and journalist, who’s written for such publications as The New Yorker and The New York Times. Boom seems like one of ABC’s big guns this coming season, so we’ll likely be seeing it in the fall.

Writers: Josh Pate and Rodes Fishburne

Details: 60 pages (January 16th, 2015 – Second Network Revision)

When I first started reading Boom, I wasn’t sure if I was reading reality or science-fiction. The U.S. has found some previously unknown oil well in North Dakota that’s bigger than any other oil well in the world? When did this happen? Have I been so wrapped up in pointless entertainment news issues like whether Robert Downey Jr. likes independent movies or not that I’ve managed to overlook the most significant find in the history of the world?

Here are some facts I learned from Boom –

1) There will be a city the size of Dallas in North Dakota by the year 2030.

2) A new millionaire is made in North Dakota every day.

3) North Dakota’s unemployment rate is currently 0%.

Considering I always thought North Dakota was a lake that existed in either Canada or Poland, I find this all very hard to believe. But assuming it’s true, today’s writers might have stumbled on the subject matter of the decade to base a TV show on.

Billy LeFever’s a dreamer. Always has been. So persuasive are his dreams, he’s even roped his wife, Kelly, into them, convincing her to head to the growing oil-rich town of Williston, North Dakota to set up a chain of Laundromats there.

But as you all know, being screenwriters, dreamers can be a little blind. We can get a little ahead of ourselves and maybe not have a Plan B. This is exactly what dooms Billy, whose truck full of washers crashes just outside of Williston. His UNINSURED truck. All of a sudden, these two have to go back to square one.

Which is really what the Boom pilot is about. Billy gets a tip about a piece of property that’s over a previously unknown oil reserve and uses a series of shady investments to buy the place from the clueless owner. He’s doing this all on blind faith. I mean, he’s pretty sure the tip is good. But he’s not positive. Lucky for him, the bet pays off when the richest man in town, billionaire Hap Boyd, offers to buy the land from Billy for a cool million.

You’d think it’s happily ever after from there, but it turns out a lot more is going on in Williston. Hap’s hated first son starts a business siphoning oil from his pop’s reserves. And the Middle East even has spies in Boom Town, here to report back about their competition. Add a local Indian Tribe who’s about to find out they’re sitting on a billion dollar piece of land and you can imagine how crazy things are going to get. Sounds like lots of exciting times ahead for Williston, North Dakota.

Here’s the refreshing news about Boom. It’s not about superheroes. It’s not about cops, or lawyers, or doctors. It’s not about a morally ambiguous anti-hero doing something shady to make a living. Well, actually, it’s kind of about that. But still, there’s no doubt that one of Boom’s biggest strengths is that it’s DIFFERENT. And that’s hard to do right now, with every writer and their mother writing TV shows.

The script smartly centers on a pair of underdogs, Billy and Kelly (everybody loves underdogs!), nobodies who’ve put every cent they have on the line and then lose it all in a car crash the second they get here (ironically pushed off the road by an oil truck). Who’s not going to root for these two after that?

Stakes play a big part in why their plight works. Remember, the more you can put on the line for your hero(es), the better. These two haven’t just invested their own money, they’ve taken all their friends and families’ money as well. Then, when Billy needs to buy the land, he borrows more money, putting them even further in the hole. If his plan doesn’t work out, he’s really f*&ed. And that’s the way you want it. You need your character to be f*&ed if the plan fails.

Another cool thing about Boom is the cast. And this very well may be the show’s secret sauce. The way this boom is shaping up (I’m talking about in the real world), EVERYBODY is coming from EVERYWHERE to be a part of it. This allows Boom to have a really diverse cast of characters, from Caucasians to Mexicans to Native Americans to Middle Easterns to even Nigerians! Not only does this keep the show feeling fresh but networks love this. They want to have diverse casts. And if it’s organic to the story, like it is here, all the better.

If Boom has issues, it may be in its 3rd Act plotting (3rd Act in TV terminology, not feature terminology), where Billy goes from owing $100,000 to becoming a millionaire in the span of two days. This happens literally within 20 pages and while the plot points were plausible enough to buy on their own, it was hard to concede all of them falling in line together. I mean, who do you know that can raise 100k in 24 hours who doesn’t have the last name of Zuckerberg?

But if you get past that one flaw, it’s a fun ride. Like every TV show, it’s going to come down to how it’s directed. But I’m excited to see how it turns out. Even the cable channels are getting stale with their ideas. It’s time we put something different on the air.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It doesn’t matter how many times you use this one, it always works. Set up something really valuable that one of your main character’s owns, and then force them to have to sell it at some point. The more personal the item is to your character, and the more emotionally attached they are to it, the better. So here, Kelly owns an emerald necklace that literally came from her 3x great grandmother. It’s priceless. When Billy needs that last 25k to buy the land plot, Kelly offers up the emerald. We GASP at the thought, since the importance of the necklace was set up earlier. Not only does this get the reader screaming “No!” when it happens, but it raises the stakes of your story as well. Because now, if Billy’s plan fails, it’s not just money that’s gone, it’s an irreplaceable piece of history.

What I learned 2: A feature script must end on a solution. A TV pilot script must end on a problem.

Scriptshadow 250 Contest Deadline – 87 days left!

Genre: Superhero

Premise: When Tony Stark accidentally unleashes a villainous robot upon the world, it’s up the Avengers to send him back where he came from.

About: Avengers: Age of Ultron was supposed to break all box office records this weekend. However, Disney never could’ve predicted when they snagged the date two years ago that Floyd Mayweather would finally stop ducking Manny Pacquiao. And hence, the Saturday ticket sales for Avengers were way lower than expected. This meant that Avengers finished below one of the 37 Harry Potter movies for the single-weekend box office record, although analysts are still trying to figure out which Harry Potter movie it actually was (because of, you know, how many there were). Still, the film made 8 quatillion dollars so Disney’s not fretting too much. This completes Joss Whedon’s contribution to the series. The next two Avengers movies will be passed off to Captain America 2 directors Joe and Anthony Russo. After that, things become interesting. The Marvel Universe will likely choose to reboot everything (from the actors to the films themselves) which is a phase they haven’t had to deal with yet. Until then, though, viva la superheroes!

Writer: Joss Whedon (based on the comic book by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby)

Details: 141 minutes

In a recent Scriptshadow Newsletter I commented how we were moving away from the dark serious world of superheroes that Christopher Nolan initiated into more fun-filled fair. If Avengers: Age of Ultron is any indication of the kind of fun we’ll be getting, please bring back Nolan.

I purposefully avoided all details about this movie going in as I wanted to see it fresh. And I noticed something curious almost immediately. “Man,” I thought, “Joss Whedon sure did an aggressive director’s pass on this screenplay.” How did I know this? Well, because literally every fourth line of dialogue was a quip. So Iron Man would say something like, “Everybody needs to loosen up.” And Captain America would reply with something like, “Says the man encased in metal.”

This would’ve been fine had it happened, oh, I don’t know, three? Maybe four times? But when it happens SEVENTY-FIVE F***ING TIMES, it’s a little overboard, don’t you think? Screenwriters all have their go-to moves. For Tarantino, it’s his long dialogue scenes where the characters appear to be talking about nothing. For Woody Allen it’s a character who drones on about the meaninglessness of life. And with Joss Whedon, it’s quips.

Part of being a good screenwriter is restraining yourself so you don’t keep going back to the well. Cause if you start doing the same thing enough, the audience begins to notice it, and then you’ve done the worst thing a writer can do, which is break the suspension of disbelief.

After the film, I checked online to see that Whedon didn’t just do a director’s pass, he’s got sole screenwriting credit! Which explained this and so much more. And by “so much more,” I mean that Avengers was basically an extended episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Heck, he even found a way to sneak a witch into the plot!

“Ultron” centers on Tony Stark’s continued obsession with pushing the boundaries of technology. He’s created an artificially intelligent being inside his computer, which quickly finds itself an exterior robot body to jump into. This robot’s name is Ultron and he really hates Tony Stark and the Avengers because… okay, let’s just be real here, because they wouldn’t have a movie otherwise.

Ultron decides that he’s really into meteors for no reason and rigs the underside of a small Eastern European city to break away from the earth, fly up into the stratosphere, then shoot back down to earth like a meteor and – I guess – destroy half of earth in the process. Although it’s never made clear how this would actually destroy half of the earth.

Despite the Avengers having the strongest God in the universe, the strongest robot in the world, and the strongest monster in the world, they determine they can’t defeat Ultron alone, and so they create… something I can only describe as a dull-colored caped crusader. Despite a lot of the superheroes trying to explain what this man is (“He’s a biological extension of an A.I. program with Tony Stark’s virtual assistant’s voice?”), nobody knows for sure. What we do know is that he’s the strongest man ever. Which gives them a fighting chance to defeat Ultron.

Putting my quipping issues on hold for the time being, I noticed a few things about Avengers 2 that I hadn’t thought of going in. First, it LITERALLY has something for everybody. It has a great actor in Robert Downey Jr. to bring in the older crowd. It has Chris Hemsworth to bring in the swooning female Fifty Shades crowd. It has Scarlett Johannson to bring in the internet-distracted teenage boy crowd. It has superheroes to bring in the kid crowd.

There’s a reason this movie will make more money than any other movie this year (yes, probably more than even my beloved Star Wars). It’s the PERFECT STUDIO MOVIE. It gets every single demo into the theater. And it does so ORGANICALLY.

By that I mean it’s not adding these things to the film specifically to bring in certain demographics. Audiences can smell when studios do that from a mile away. The premise of a team of superheroes trying to save the world naturally hits every demo out there. Which is really rare.

And yet, as a standalone story, Avengers: Age of Ultron, fails. It wasn’t as bad as the Mayweather-Pacquiao fight, but it makes that classic mistake all superhero sequels make – that MORE must be better. More superheroes. More villains. More battles. More storylines. And that NEVER works. And I know that Joss Whedon knows this. I’ve heard him talk about it before.

Look at a movie like Captain America 2, which many consider to be the best Marvel film so far. It’s no coincidence that that film was one of the smallest in scope of all the Marvel movies. This forced them to be more creative and come up with better ideas (instead of bigger ones). Two of the most memorable sequences in that film took place in a) an elevator. And b) a stopped car! And both were FAR more compelling than Ultron’s giant city floating up into the clouds.

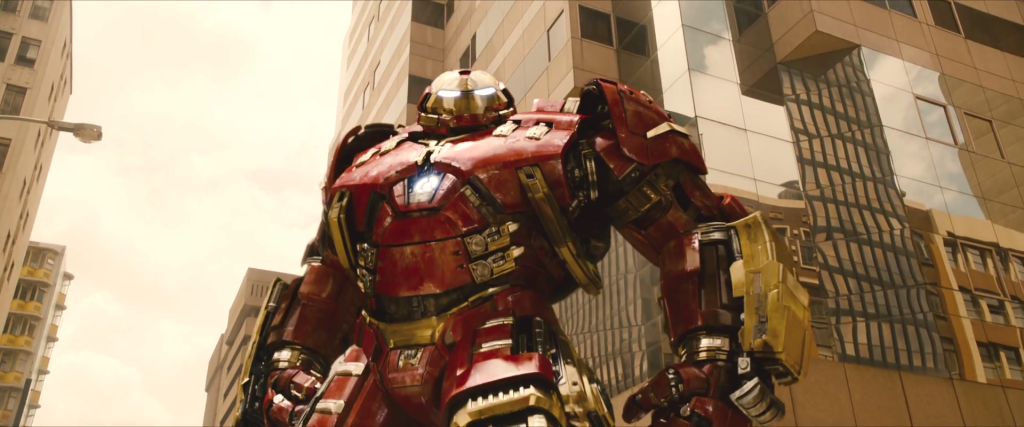

Or take Ultron’s best set-piece: Hulk vs. Iron Man. That was a cool fucking set piece! I loved this “Iron Man Emergency Pack” that shot down from a satellite and kept equipping Iron Man’s suit whenever the Hulk would bust it up. Genius idea there.

And yet I FELT NOTHING during the fight. Why? Because it had nothing to do with anything. There were no stakes attached (story or emotions-wise) at all. Let’s say Iron Man loses the fight. The Hulk then what? Kills 700 people instead of 500 before turning back into Bruce Banner? I didn’t even know what city they were in so why would I care about who died? It’s clear the sequence was put there for one reason and one reason only – because it was cool. And that’s the worst reason to put a set piece into your screenplay. You add something to your story first BECAUSE IT MATTERS. Then you figure out how to make it cool.

I’ve said this before – it’s very difficult to steer a screenplay for a movie this big into any sort of creative vision. You’re dealing with too much money and too many powerful forces wielding their influence over the final product. Still, I was hoping for something a little better than what I got. Here’s where I’d rank Ultron along with the rest of the Marvel films.

1) Iron Man

2) Guardians of the Galaxy

3) Captain America 2

4) Avengers

5) The Incredible Hulk

6) Captain America 1

7) Avengers 2

8) Thor

9) Iron Man 3

10) Iron Man 2

11) Thor 2

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Avoid using premonitions at all costs. They’re the sloppiest most hackneyed storytelling device there is, and are almost always used as a cheat. In screenwriting, you must constantly come up with REASONS for why your characters do things. And the clearest most powerful reasons are always the best. Indiana Jones needs to find the Ark because if he doesn’t, Hitler will. A premonition is the opposite of that. It’s a vague vision that holds no weight in reality. Maybe it will happen, maybe it won’t. So it doesn’t carry nearly the punch that REAL motivation does. Look at a couple of really bad movies that have used this device in the past. Matrix: Revolutions (Neo has a premonition that Trinity will die). Star Wars: Episode 3 (Annakin has a vision that Padme will die). And here in Ultron, we have Thor going off on some tangent adventure because he had a premonition. It’s no coincidence that that ended up being the most pointless thread of the entire movie. — The one genre premonitions can work in is horror films. But they must be intricately woven into the story. They can’t just be slapped in there to get your character to do something you’re too lazy to come up with a reason for otherwise.

Keep those Scriptshadow 250 entries coming. In the meantime, here’s another batch of scripts to check out. The amount of horror scripts sent in this week outranked all other genres 4 to 1. You guys really like horror! I was able to slip in a few non-horror scripts though, for those who don’t want to get their scare on. Make sure to give the writers feedback in the comments section!

Title: Vampires in Sunland

Genre: Horror

Logline: A young girl coming into adulthood must battle a motley group of vampires who have taken her boyfriend hostage.

Why you should read: I wanted to try my hand at something more commercial, for my scripts usually are not, and so “Vampires in Sunland” (Sunland, California) was the result. As a fan of the film Lost Boys, I wanted to bring a little of that flavor back into the vampire genre, but not without adding my own dash of spices. In this case a demonic element. I also wanted to play with gender roles, in this the female is the heroic action star and the male is the “mansel” in distress she must save. As well as a main villain who can change genders whenever it wants to best suit its victims.

Title: Ghostlight

Genre: Horror

Logline: When a series of strange murders occur during rehearsals for the school play, an awkward drama geek must find out who or what is behind the killings- or there will be no opening night!

Why You Should Read: I’ve been a drama teacher for the past ten years, and been in the theatre for over twenty- I know theatre, it’s superstitions and mystery. I also know teen agers, what they like and how the speak. I have had my students read the script, and across the board they love it and are begging me to get it made. Think “Cabin in the Woods” meets “Glee.”

Title: Inspired

Genre: Crime/Drama

Logline: During the hedonism of 90s Hollywood, a desperate writer’s career unexpectedly blows up when he starts writing about the crimes he’s committing, putting his Hollywood success on a collision course with the law.

Why you should read: My previous submission (Devil in You, Oct ’14) was relatively well received, “the minimum level of quality required to get made” is basically how it was described. So not outstanding, but still readable. — I believe I’ve progressed with this script. Hopefully I’ve been able to take on board some of the notes from yourself and the SS community about issues in my previous script in order to take ‘Inspired’ to the next level. — 1990s Hollywood was a crazy time, the town’s wealth was reflected in the insane ‘spec wars’, huge actors salaries, and notorious parties. I hope all of that and more is reflected in the script.

Title: The Big Decay

Genre: Film Noir/Horror

Logline: A private detective finds himself embroiled in a scandal that involves junkies with zombie-like behavior.

Why you should read: Some of my favorite films are classic film noirs such as Out Of The Past, Double Indemnity, and The Asphalt Jungle. My other favorite genre is horror movies. I thought to myself, “What if I combined these to create something unique?” With that as my basis, The Big Decay was born. I’m not sure if I’m considered a professional, or amateur. I’ve written and produced a straight to DVD horror film, and I’ve produced other feature films. Technically, I guess I’m a professional. However, I have no industry contacts, and no agent.

Title: Universal Love

Genre: Romantic Comedy

Logline: A female writer suffering from writer’s block develops a romantic bond with a man who she thinks is perfect, unaware that he is the alien from her story.

Why You Should Read: I am Kristopher M. Newcome. I enjoy writing and reading screenplays. The film’s logline took second in the Ultimate Logline contest. It won in March under the title, “Space, Time, and Beyond.” The category was female protagonists. I get to attend Scriptfest at the end of May. I get to listen to several speakers including Diablo Cody, and pitch my script to Twenty executives. I think it is really amazing what you do, and I hope you enjoy the script if you pick Universal Love to review.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Biopic

Premise (from writer): In 1964, writer Gene Roddenberry struggles to get his vision on television – a show called “Star Trek”.

Why You Should Read (from writer): Three reasons. One – unlike other biopics which give you the whole Wikipedia routine, my script focuses on a year-long period in a man’s life, during which he has a clear goal. Two, it could generate a discussion on the act of using licensed properties you do not own in a spec written as a sample. (Like “Wonka”, which I am certain will not be made unless Roald Dahl’s zombie corpse approaches a production office, gobstopper in hand, and signs off on it while offering casting notes: “Two words: Get Gosling.”). And, three, my script comes from the heart. My father passed on in ’91, when I was kid, and one of the things he instilled in me was a love of science fiction, particularly “Star Trek”.

Writer: Jack McAuley (based on the books, “Inside Star Trek” by Herbert F. Solow and Robert H. Justman, “Star Trek Creator” by David Alexander, and “Star Trek Memories” by William Shatner with Chris Kreski

Details: 106 pages

Man, there were some HARSH reactions to last week’s batch of amateur scripts. Let’s remember that we’re trying to be critical but supportive. The idea here is to help writers improve.

Because no single script won out in AO, I’ll be reviewing the most talked about entry, “To Boldly Go.”

I’ll start off by saying the Black List LOVES these scripts. In fact, if the Devil came to me and said, “If you don’t write a screenplay that makes the Black List this year, you’re coming down to hell with me,” the type of script I’d choose to write wouldn’t even be a contest. I’d write about a famous author’s early life and the influences it had on his greatest work. It’s like Black List crack that set-up.

And the scripts don’t even have to be that good! From the ones I’ve read, I’d say at least half are boring. It seems that the idea alone carries enough weight to overshadow the execution. It’s this secret formula that’s only talked about in basements between successful writers (“Can you believe how rich we are now? All we had to do was write about an author’s early life!”)

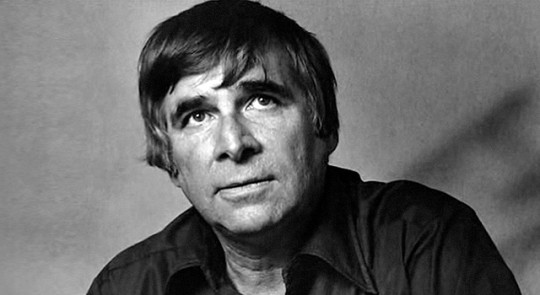

To Boldly Go starts off introducing us to a young Gene Roddenberry and his father, a police officer. The two are strolling through the neighborhood when the father makes a racist remark after spotting a young black boy. This is followed by a montage that covers Roddenberry’s service in World War 2 as a pilot and his eventual transition into commercial piloting.

After Gene nearly dies in two plane mishaps (one a crash), he decides to move into a job less suicidal: screenwriting (clearly, Roddenberry has never written before). He moves to Los Angeles and finagles his way onto some TV shows, until he comes up with an idea for his own show, a science fiction series where a space ship crew travels the galaxy. This was in 1964, at a time where nobody had attempted something of this scope on television.

The remainder of the story chronicles the making of the show, everything from finding a director to casting the part of Spock. When the studio doesn’t like what Roddenberry comes up with, they give him a second chance for some reason, and he recasts everyone (save Spock) and turns the show into more of an action-adventure. Although the show was cancelled after three seasons, it would later inspire five spin-off series and twelve feature films and become one of the most recognized science-fiction brands ever. It is the original “Universe” approach that every studio in town has adapted today.

One of the things I still have a hard time grasping in screenwriting is theme. Sometimes it feels so clear and other times wholly elusive. But today’s screenplay helped me understand theme about as well as I’ve ever understood it. And that’s because there wasn’t any. And that’s what kept To Boldly Go from working.

Instead of there being a unified message to keep going back to in To Boldly Go, we got a hodge-podge of events that happened to Roddenberry over the course of his lifetime – mostly in relation to Star Trek. Everything from Roddenberry’s infidelity to escaping a plane crash to looking for an associate producer. Put frankly, the message was all over the place.

I went back to the comments for Amateur Offerings, and someone brought up how interesting it was that Roddenberry’s father was a racist, and how that was an inspiration for him to create a racially diverse cast on Star Trek.

Now THAT to me is a story. THAT to me is a theme you can hang a movie on. And yet, it’s BARELY covered at all here.

Instead, we get the technical details of how the show came together (the hiring of the costume guy, the production designer, the music guy). There’s no drama in that (or at least there wasn’t any here). Even William Shatner, who it’s well known is one of the most difficult people ever in show business, is rosy and happy and agreeable in this.

If you know, going in, what your theme is – say it’s a man hellbent on changing the white-washing of television shows because his father was a racist – then it’s easy to figure out what does and doesn’t belong in your script. Take Roddenberry’s infidelity. Can infidelity lead to drama? Sure. But since it has no bearing whatsoever on a man trying to break down racial barriers in television, there’s no reason to include it.

Personally, I think that’s a great storyline to focus on – the race stuff. Because nobody knows that. Everybody knows that Spock has weird ears. With a biopic, you have to give us the stuff we don’t know and a young boy who was so affected by his father’s racism that he wanted to change the world with a multi-ethnic show – that’s a fucking movie right there. I’d go see that. What I wouldn’t go see is a highlight reel of kooky things that happened on the Star Trek set. There’s no depth to that.

This leads to my second problem with the script which was the lack of conflict. For a show that was so cutting edge and unlike anything that came before it, where was all the resistance? Where was that one executive who hated the idea and was constantly trying to kill it? There was no drama on that side of the story. It was, again, technical historical bullet points combined with occasional goofy memories (having to stop filming because pigeons were on the set).

For example, when the show’s pilot goes bad, they’re just offered another pilot on the spot. The characters don’t have to do anything, don’t have to earn anything. They simply get a call that says, “We didn’t like that. Try again.” The last thing you want to do in any script is magically solve problems for your characters. You need your characters to encounter obstacles and then to overcome them themselves, regardless of if that’s not the way it happened in real life.

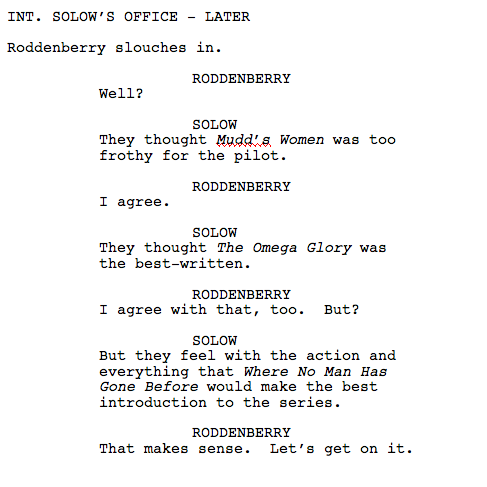

This scene, in particular, embodied the casual, “no problem’s really that bad” nature of the script. It comes after the network reads the three potential scripts for the new pilot.

As you can see, even when there are problems, they’re just solved instantly. All the characters have to do is listen.

There are some dialogue issues here as well. Mainly, the characters sound too stiff, technical, or robotic. Take this line from Roddenberry when he’s told he has to reshoot the pilot: “But they want me to get rid of Spock. I am therefore going to keep him, anyway.” I don’t know anybody who talks like that who isn’t sitting on a leather chair in front of a fireplace smoking a pipe. How bout, “They want me to lose Spock. They might as well tell me to lose space.” Relax the dialogue. Have a little more fun with it. Contractions, overlapping, less formal-speak. All those things will help.

I do think there’s more leniency in the industry when it comes to these scripts. A lot of people are just keen to go down memory lane. I remember that’s exactly how that Black List Chewbacca script played out two years ago. But for me? I need more. And I think writers should demand more of themselves as well. Give us a unifying theme. Give us more conflict. More drama. Little highlights here and there are fun. But they shouldn’t be the centerpiece of your script.

I hope these notes were helpful for Jack because I do think there’s a story here somewhere and with the industry falling over itself for these kinds of scripts, I think it’s worth figuring out.

What did you guys think?

Script link: To Boldly Go

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Unless it’s a conceit that’s built into the premise, repeating things in screenplays very rarely works. I lost a lot of interest when we went through this whole pilot only to be told that we would now participate in the exact same process for a second pilot. I suppose if the second run-through is significantly different from the first, it might work, but this one wasn’t. It felt like the same general issues (casting, figuring out the script) that we’d already dealt with. In a movie like “Edge of Tomorrow,” the repeating structure is an essential component of the premise. Here, it just feels like we’re doing the same thing over again.