Okay so it can be a little hard to get these posts up while reading Scriptshadow 250 scripts, hence the delays in posting and the no official post today. With that said, I did get a chance to see ROOM last night and wanted to share my thoughts with you. In short, holy shit, this might be the best film of the year.

Usually when you have a film that only deals in emotions, and specifically one that deals in negative emotions, the movie can feel like a melodramatic mess. But ROOM avoids this due to some amazing acting and some crafty screenwriting.

For those who know nothing about the film but plan to see it, I’d suggest not reading this review, as I do go into spoilers. But, to be honest, this movie isn’t about spoilers at all. It’s about relationships, particularly the relationship between a mother and her son.

It follows Joy, a young women who was kidnapped by a man pretending to have a sick dog seven years ago. She’s since been stuck in this small secure room that’s impossible to get out of. Her captor has raped her every day, and five years ago, she had a little boy, Jack. The unique thing about the story is that we experience a lot of the world through Jack’s eyes. And this room is all he knows. He has no idea what the real world is really like.

This leads to one of the most harrowing dramatic scenes you’ll see all year. Joy’s had enough and is ready to escape. But to do so, she has to sacrifice her son. After setting up an extended fake illness to make her captor believe Jack is dying, she teaches Jack to pretend to be dead, then rolls him up in a rug and, the next time her captor comes, convinces him that Jack is dead and needs to be buried.

Of course, Jack is really alive, and he’s been taught to jump out of the flat bed of Captor’s pick-up truck and run for help when the truck stops. What makes the scene so amazing is that Jack HAS NEVER EXPERIENCED THE REAL WORLD BEFORE. Imagine that all you know is a 10 foot by 10 foot room and then having ONE SHOT to save yourself and your mother’s life, and you have to do it an endless world you’ve never seen before.

I don’t think my heart has ever beaten so fast.

But Room is captivating for so many other reasons, one of which is the screenplay itself. The script is divided into two halves. The first half occurs in “Room” and the second half in the real world as they try and adjust to this new completely different life. You have Joy, who thought once she escaped she’d be happy, but is instead traumatized by the event and therefore miserable. And then you have Jack, who’s trying to learn to live in a strange world with an infinite set of new rules.

One of the most heartbreaking moments is when Jack asks his mom if they can go back to Room. That’s all he knows. And because Joy protected him so well while they were in that room (pretended that all was okay), he actually liked it there.

Here’s where things get interesting though. As a screenwriter, all I kept thinking was, “This movie is going to die once they get out of Room.” Because think about it. When they’re in Room, the goal is clear – get out of Room. Escape. But once you’re out, where is the narrative engine? What are the characters trying to get to now?

Indeed, the second of the script is not as structured, but by God somehow they make it work. We’re obviously going to go along with the characters for a few scenes once they get into the real world. We’re curious to see Joy reconnect with her parents and Jack make sense of this alien universe.

But what then? How do you keep the audience engaged?

They pull this off by doing something really clever. Joy has a mental breakdown and has to go get extended treatment. This leaves Jack alone at the house with his grandparents. The narrative thrust, then, comes from something really odd. We want Jack and Joy to be together again. We spent 60 minutes with these two inside a small room together where the two were each other’s world. Something feels unfinished if they’re apart. So there really is no “goal” per se from this point on. We just need to see the two back together again.

And when Joy finally does come back and we get that satisfaction, they add one last piece of narrative thrust. Jack needs to see Room again. And it totally makes sense. This was this kid’s entire life. He has an incredibly strong attachment to it. So he needs to go back. And so does Joy, in a way. They need that closure. And man is it intense when they do go.

This is a small movie that doesn’t have anything other than acting and writing driving it. But it does such an amazing job on those two fronts that I would recommend all of you go see it. It’s top-notch stuff.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[xx] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m all about character goals driving the narrative, as you know. The second half of Room has made me reconsider some things. Maybe it’s okay just to have something unfinished driving the story. Two characters seeing each other again. If we love those characters enough, then we don’t need goals. We just need that closure of seeing the two with each other once more.

TV Pilot Tuesday is back. And with it comes the buzzy phrase, “the strange attractor.” What is this strange attractor? Why do people in the comments section talk about it so much? And does Quarry contain it? Read on, my friends, read on.

Genre: TV Pilot – Drama

Premise: A Vietnam vet comes back from the war and when he can’t find a job, is forced to become a hitman.

About: This one comes from show creators Graham Gordy and Michael D. Fuller. The show will play on Cinemax and become one of the underrated network’s steadily growing group of gritty shows it hopes will turn it into the next AMC. In fact, listening to Gordy and Fuller talk, you can practically hear the influences of Breaking Bad and Mad Men, as they want to use their hard-boiled main character to define the 70s, and see how he eventually responds when the polar-opposite 80s arrive.

Writers: Graham Gordy & Michael D. Fuller (based on the novels by Max Allan Collins)

Details: 61 pages

You know, it’s funny. As I was reading this, I kept thinking to myself, “This feels really familiar.” There was a show on Sundance called “Rectify” about a tortured quiet individual who’d just been released from prison after serving a sentence for murder. We watch him as he tries to integrate back into a changed society and a community that doesn’t trust him.

So what’s Quarry about? It’s about a man coming back from war trying to integrate back into a changed society dealing with a community that doesn’t trust him. So I check IMDB. What do you know? It’s the SAME writers. Truth be told, I liked the first couple of episodes of Rectify. But it became too slow for me, too contemplative, with one too many “tortured hero looks off in silence for 30 seconds” shots.

I was hoping Quarry would be different. Let’s find out if it is.

32 year-old Quarry has just gotten back from Vietnam with his buddy, Artie. The two seem to be doing all right. No limbs missing. No scars that stretch from one end of their faces to the other. These guys just want to get home to their wives and start living a normal life again.

But that’s not going to be easy. As we find out from the screaming protestors just outside the airport, everyone’s up in arms about a mass child massacre that took place back in Nam that our two soldiers may have taken part in. Quarry must look at giant pictures of dead children thrust into his face as he tries to get to his car.

But all of that fades away when Quarry gets home and sees his wife, Joni. As Gordy and Fuller put it, “If you have to fight a war, she’s the woman you fight it for.” The two make love like it’s going out of style and that begins Quarry’s new war – finding a job.

The problem is two-fold. There aren’t a lot of jobs to have, and everyone’s so pissed off about this Quan Thang massacre that even the jobs that are available aren’t available to HIM. Little does Quarry know, he’s been trailed ever since he got home. And he’s finally approached by the trailing gentleman, a guy who likes to refer to himself as, “The Broker” (for whatever reason, I kept thinking of “The Prospector” from Toy Story 2 whenever he came around).

So the Prospetor, err, I mean The Broker, offers Quarry a lifeline. Tells him he’ll give him 50 grand if he’ll start killing for him. Not good people, he assures him, bad people (aren’t they always?). As he points out, it won’t be any different from what you did over there, except this time you’ll be doing it to people who actually deserve it.

Quarry Refusal-of-the-Calls that shit, but when Artie takes the position he rejected, he’s forced to hop in and help. Without getting into spoilers, let’s just say that Artie’s hit doesn’t go too well. This brings Quarry into the situation on a more personal level. When he agrees to kill ONE person just to get back on his feet, he’s offered his first mission. That mission will be a shocking one – as the man he follows takes him right back to his very home, where his wife opens the door, and lets the man inside, a man, Quarry sees, who is now kissing his wife.

There’s been a lot of talk in the comments of late about the “strange attractor.” It’s something I don’t talk about a lot but maybe I should. I suppose I always considered the strange attractor to be a given, but I must remember that there are no givens in screenwriting.

The “strange attractor” is basically what makes your idea unique. A couple of brothers going to a remote island to connect with their estranged aunt? No strange attractor there. A couple of brothers going to an island of dinosaurs to connect with their estranged aunt, who runs the place? Now you have your strange attractor.

Take the time travel out of Back to the Future, the superheroes out of Avengers, the “stuck alone on Mars” out of The Martian, and you’ve lost all of their strange attractors. Now you might say, “Well duh, Carson. You don’t have a movie if you take those things away. They’re the entire film!”

Yeah but see here’s the thing. I READ all those scripts that have those things taken away. I’ve read that indie script about a guy who tries to reconnect with his parents. That is, essentially, Back to the Future without its strange attractor. I’ve read that boring script where a group of friends get into shenanigans in their middle-of-nowhere town. That is, essentially, The Avengers without its strange attractor.

Getting back to Quarry, I was looking for a strange attractor, and I had trouble finding one. Everything here is familiar. Guy comes back from war. World isn’t welcoming. He needs to find a job. We’ve seen all that before, right?

The most thrilling aspect of the concept is the hitman stuff, but is that a strange attractor? Haven’t there been so many hitman movies/shows at this point that there’s nothing “strange” about it?

To be honest, there was only one SPECIFIC component to the script, which was the Quan Thang Massacre. That’s the only thing you couldn’t see from watching any other show. And I struggled with whether that was enough.

Because the thing is, the writing here is strong. The character work is strong. You feel like you know these people. You relate to these people. And there’s something to be said for that. In fact, one of the things I struggle with is the balance between the strange and the familiar. Sure, you want that strange weird “we can’t get this anywhere else” component to your story. But if the characters are all weird, inaccessible, or boring, it doesn’t matter. We need to understand and relate to the people in your story if we’re going to care.

I’m sure everyone here has experienced that awkward feeling of walking back into a world that used to be your entire life, and now has completely changed. Shit, I used to feel it every time I flew back home for Thanksgiving or Christmas. And on that front, Quarry does an excellent job. It captures that feeling, just like Rectify did.

I’m just wondering if this is another Rectify situation where the first two episodes are good, but then we’re just treading water since there IS NO strange attractor – nothing that sets it apart from anything else. I liked the way the story unfolded. I loved how Quarry’s first hit turned out to be banging his wife. It made the script worth reading. But does this show have legs? I guess that’s something we’ll only find out with time.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A nice way to add a little spice to a fight is to give both parties something they’re after during the fight. Because when you think about it, a basic fight is pretty boring. Two people swinging away in an obviously choreographed ballet. But if they’re fighting to GET to something, now the fight has a little extra kick. The classic example of this is in any Jackie Chan film, where a gun has gotten away and both guys are fighting to get it. But be creative. It doesn’t have to be a gun. It can be whatever object is important in that moment of the movie.

Genre: Horror

Premise: (from Blood List) Having moved into a “clean house” to treat his auto-immune disorder, 11-year-old Eli begins to believe that the house is haunted. Unable to leave, Eli soon realizes that the house, and the doctor who runs it, are more sinister than they appear.

About: This was the NUMBER 1 SCRIPT on this year’s just released Blood List, a list of the best horror/thriller scripts of the year, and the annual kick-off for screenplay lists. Today’s script was written by David Chirchirillo, who does have a few produced credits, but none you can come back to your hometown to and proudly use as way to say “fuck you” to all the people who never believed in you, which is, as we all know, the only reason we write. Quick side fact about The Blood List. It included a script that was posted here for Amateur Offerings just last July (Unlawful, by Carver Grey). Just goes to show – if you write a script and it gets a good reception on the site, good things can happen to you! So keep those submissions coming (details at the top of the review I just linked).

Writer: David Chirchirillo

Details: 98 pages (undated)

Note to all. For your future sanity, do not ever, and I mean EVER, drive anywhere at 1 am in Los Angeles on Halloween. Not only are there 3 million drunk hipsters stumbling around in the middle of the road, but since everyone knows someone who knows a make-up artist here, everybody actually looks like the character they’re portraying, which results in a particularly trippy experience.

Here are some of the people I ran into who could’ve easily been mistaken for the real thing: The Hulk, Homer Simpson, Elsa from Frozen (but with a short skirt), Netflix and Chill (A guy with a shirt that said “Netflix” and then a bag of ice), an Ipad, an entire flash mob of Donald Trumps, the naked white Prometheus alien, Groot, Kylo Ren, a somehow working E.T. doll/man, and a guy who was dressed up as half Jake Gyllenhaal from Nightcrawler and half Jake Gyllenhaal from Southpaw.

I bring this all up because I was traumatized by the experience and realized the only way I could move past it was to review ONE LAST HORROR SCREENPLAY. Call it script therapy, but I needed this.

11 year-old Eli has a serious auto-immune disorder, the kind that places him a few dust pans short of Bubble Boy. But lucky for him, his parents have found a unique place that treats this disorder.

So Mom and Dad join him inside a home that has the most advanced clean-air filtering system in the world. The home is run by a woman named Dr. Isabella Horn, who looks a little bit like a polygamist’s wife, and claims to know how to cure Eli.

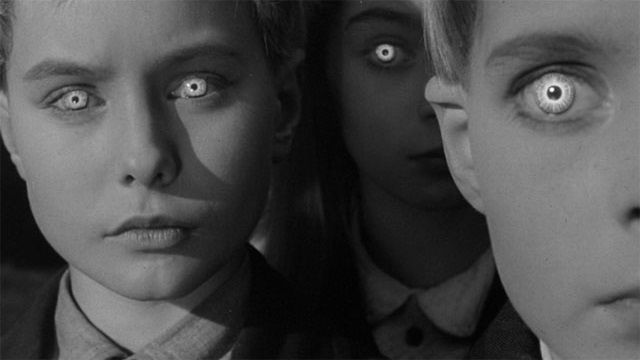

Eli likes the place at first. Being able to run around sure beats putting on a hazmut suit and eating your cereal through saran-wrap, but then he starts seeing strange shit around the home. Like a kid his age wandering around. An older woman who always seems to be screaming, and some creepy pale dude who needs a serious trip to the tanning salon.

The ghosts eventually orchestrate the age-old ghost custom of “charades talk,” which leads Eli to a hidden room that tells him that everything about this place is a lie. But the real shocker is what happens next. Eli learns that it isn’t just this house that is a façade, but his entire life. Can Eli escape from this hell-hole? After learning the truth, does he even want to? These are just a couple of the questions posed in…. Eli!

“Eli” is a script that shows promise. But it ends with a payoff so out-of-left-field, I’m not sure even the Kansas City Royals could’ve caught it.

I can’t discuss what that ending is without getting into spoilers, but I admit having an ending this weird will get readers talking and that puts your script well above the competition. The majority of horror scripts are by-the-numbers retreads with the requisite number of spooky components (1.5 characters crab walking backwards through hallways, 7.8 jump scares) and not much else. When you go bold with your ending, at the very LEAST, you’re going to get people talking.

Speaking of “retread,” here’s the big lesson I learned from today. Your goal with a horror script – and really any script – is to find fresh ways into proven ideas. That last part is key. PROVEN IDEA. Because that’s the part the studio requires in order to purchase your script. They need a formula that’s been proven (and thus can be marketed).

The “fresh” part is what allows you, the writer, to explore things within that proven formula that haven’t been explored yet. This is where you get to show off YOUR talents, your originality, your imagination. This fresh angle can come from story, from setting, or from character. Eli does it with setting. We’ve seen haunted house movies before. But we’ve never seen one inside an air-sealed germ-centric home. This small twist gave David the ability to explore things that haven’t been explored before in this genre.

And that’s what kept me engaged. I was unfamiliar with the setting and wanted to know more. Think about that. I’ve been inside a billion haunted houses in the movies. But not one with these kinds of rules. That makes me want to learn the rules. That makes me curious. That makes me intrigued to see how this particular set of rules is going to impact the story.

This seems like a minor point but it may be one of the most important you’ll read on the site. If a reader has been down a road before, all they’re thinking about is getting home. But if you take them someplace they’ve never been, they want to stick around and explore.

Character-wise, “Eli” was good but not great. Friday we discussed how the main character was impossible to root for. Eli is the opposite. He’s a kid (innocent children are easy to root for) who has a disease that’s robbed him of his childhood. Who’s not going to root for that guy?

Where “Eli” drops the ball is with the parents. First of all, I didn’t like that the parents joined Eli in the house. The whole idea with horror is to make things as isolated and hopeless and scary as possible for your protagonist. Here we give Eli two strong adults who love him and protect him throughout the script. For that reason, when things start to get scary, I wasn’t worried for Eli.

On top of that, the parents were on the same page with everything. So there was no conflict or issues between them. In most horror movies about children, either one parent is out of the picture or the child is adopted (creating a coldness between him and the parents). You saw this in recent horror films, It Follows, The Babadook, and The Final Girls. And can even see it as far back as The Exorcist. Something about two parents screams “safety,” and that’s the last thing you want your audience to feel when they’re watching a horror film.

Now later, I found out why Chirchirillo had to include the parents. And I suppose I’m inclined to agree that they were necessary. But I still would’ve created some sort of conflict there so there was at least SOME instability in that relationship. Again, the more stability you have in a horror film, the more boring that horror film probably is.

I’ll give “Eli” this. It holds your interest until the very end. I’m still not sure I liked the ending. But I wanted to find out what happened. And if a script achieves that, at the very least it’s worth checking out.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re writing a horror film about a child, it’s best to give them only one parent, and preferably, you want to make that parent the mother. A big adult male screams “safety” to your audience, and that’s the last thing you want your audience to feel. Of course, you can play with this trope (just like you can play with any trope in screenwriting). For example, you can give your child protagonist a single father and place him in a wheelchair (maybe give him MS?) so he appears weak to the audience and incapable of protection. But yeah, if you want to scare us, don’t make your young hero’s father Vin Diesel. Chances are, we won’t be too worried about him.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Horror/Slasher

Premise (from writer): Deep in the twisted and lawless labyrinth of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, a hip sociologist named Vega and her dirty gutterpunk friends are viciously hunted by the Lurkers, a pack of deranged, homicidal hobos — or maybe something even worse.

Why You Should Read (from writer): It’s always a lucky day when an idea picks you. Here, I had no desire to draft a horror screenplay, but frequent walks through San Francisco’s parks got me obsessed with what goes on there after dark. I mean, if the City streets are this sketchy during the day, then the nighttime park must be a fucking murder zone. And so the Lurkers were born, and now I’m half convinced they’re real. Definitely dirty business. — I’m more than a little over the current state of horror movies, so this is my effort to take it old school, with a focus on characters and a slow build. But for the shots of San Francisco it would cost little to make, so I hope I can convince an edgy director to take a chance. — Thanks again for all your hard work, Carson, it’s a real inspiration.

Writer: Todd Scott

Details: 87 page

Finding a horror idea isn’t that difficult. You simply identity something that scares you and build a story around it. I don’t think there’s anyone who hasn’t walked down that dark street late at night, saw that homeless person sitting or standing there, and thought to yourselves, “What if this man just went crazy and tried to kill me?” So I completely understand the appeal of building a story around that idea.

Here’s the problem though. Lrkrz is stuck in genre no-man’s land. Is it a zombie movie? Not really. Is it a slasher movie? Kind of. And that’s an issue. When a movie gets stuck between the cracks, it can slip through them. We saw it just a few weeks ago with Crimson Peak. A horror movie? Maybe? A ghost story? Possibly? A box office bomb? Definitely.

That had me wondering if Lrkrz could survive the same night its characters got stuck in. But here’s the good news. If you write something great, it transcends genre. People don’t care because they’re just happy to see a good movie. Let’s find out if Lrkrz was able to achieve that rare feat.

Vega is a beautiful 20-something latina who lives in San Francisco. She writes for a local paper, and has been working hard on a story about San Francisco’s “traveller” community, which is a politically correct way of saying, their “gutterpunks.” For those of you who’ve never been to San Francisco, it’s one of the most beautiful cities in the world. But it has one drawback – its rampant teenage homeless problem. These dirty aggressive vagrants, who aren’t afraid to use the very sidewalks you walk on as their toilets, are a stain on your memory of the city that cannot be erased.

The gang we hang with here have names like Mama Kat, Yahtzee, Shine, and Dusk. And their community is an open one, which makes them more than happy to give Vega access to their group. They honestly believe they’re part of a “movement” (being lazy is a movement?) that will change the way people live in the future. So they take Vega into their favorite parks, get drunk, get high, and tell her all about the wonderful lifestyle they live.

But something strange is a-brewin. Certain homeless men are walking around with blackened eyes. These men can move faster than Neo, are stronger than The Rock, and are set on crushing and killing any living being in their path, particularly – it seems – these gutterpunks.

It just so happens that it’s the vagrants’ big night to show Vega their lifestyle when these “lrkrz” go crazy. It’s the gutterpunks unbridled belief that the entire world is their playground that gets them in trouble. It starts when they start coupling up and heading off to screw. That’s when the Lrkrz attack. And when I say “attack,” I mean “attack.” Like one guy gets his head smashed in like a watermelon.

Because our group is so high and drunk, it takes longer than usual for them to realize what’s going on. And when they do, their goal becomes simple: Get the fuck out of this park! But it seems like wherever they go, more and more of these lrkrz appear. And that means they’re probably screwed. As Vega espouses when the chips are down: “I’m going to die in a Forever 21 sweater.” I don’t know if Vega’s going to die. But I can guarantee that a lot of these people are going to die. And I think the question that bothered me most as I finished Lrkrz was, “Is that a bad thing?”

I can see why Lrkrz won the weekend. As someone pointed out in the comments, it’s the only script with a voice. Todd’s the only one who bothered to infuse some actual personality into his writing (“VEGA looks like shit. She’s a beautiful twenty-something latina woman, but in the elevator mirror all she can see is last night’s make-up, clothes from off the floor, jizz stain on her skirt.”). There’s nothing worse than boring by-the-numbers writing. So Lurkrz gets an A+ in that department.

But despite personality bursting from every page, Lrkrz starts to display a critical problem. There was no one to root for! You’ve got the gutterpunks themselves, who are so dirty and annoying and lazy, you can’t possibly like any of them. That leaves us with Vega herself. And as you can see from her intro, she doesn’t exactly ooze Tom Hanks-level likability. She rails against her subjects the second they turn their back. And her life is just as lurid and directionless as theirs (she drinks, gets high, parties, fucks randoms). That choice might have been on purpose, a commentary on the hypocrisy of her stance on these kids. But I just didn’t like the woman. And that left me with no one to root for.

It’s an important question to ask when you write a screenplay. Who is it that the audience is going to root for here? It doesn’t always have to be the protagonist. But it has to be somebody. And that means considering how you’re going to make that character – gasp – LIKABLE. If you’re not at least considering that question, you’re not doing your full homework as a screenwriter.

Lrkrz’ big strength also turned out to be its biggest weakness. What pops about this script is the authentic realistic bickering between all its characters. I definitely felt the personality of each and every character come out (even if I didn’t like them). But that wandering authentic babbling came at a price. The story started to wander as well. There are only so many scenes I can listen to of these kids’ random opinions. That may work in real life. It doesn’t work on the page when we need some sort to structure to guide us, to remind us where all of this is going.

I mean, what are we looking forward to once they realize they have to escape the park outside of escaping the park? Yesterday we had the reveal of a 200 year-old wellness center to try and figure out. Tuesday we had the revelation of how a little boy became a doll. In Lrkrz, there is no mythology. It’s just people trying to run out of a park. And that’s fine. Not every movie needs to have some deep-set mythology. But if your genre-piece DOESN’T have mythology, it needs to have strong characters we’re rooting for. And that was the thing. I didn’t like any of these characters so I didn’t care whether they got out of the situation alive or not.

I think, moving forward, Todd should work on BALANCE. Instead of making every single character a fast-talking hard-partying trainwreck, look to build more variation into everyone. And always consider the “root for” question. Nobody’s going to root for a character just because you created them. You must GIVE THEM A REASON to root for that character. And Todd didn’t give me a reason to root for anybody. That’s what doomed Lrkrz. And that’s what I’m hoping he’ll learn for the next script. I wish him luck cause he’s very talented.

Script link: Lrkrz

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Today’s “What I Learned” actually comes from BellBlaq, a former professional reader who gave some great notes to all the entries last week. I read the opening of his notes for Lrkrz and couldn’t agree more: “Reads to me like all of the disdain in this piece comes from you, the writer. I want to be immersed in and enamored with the story, not distracted by how you feel about some shit.” I definitely got that “I hate everything” vibe when I read the script as well, and it probably was a big reason for why I didn’t like anyone. Because the writer didn’t like them either! All the emotions and feelings in a script should come from the characters and the story, not the writer’s opinion about what he’s writing. Never forget that.

Genre: Horror

Premise: A company man is tasked with recruiting a rogue board member who’s disappeared while attending a remote “wellness” center in Switzerland.

About: I’ve always liked Gore Verbinski. A lot of people gave him shit after cashing in with the Pirates’ sequels. But before that he did the offbeat “The Weather Man,” the awesome, “The Ring,” and the cool underrated flick, “The Mexican.” He even made one of the most unique animated films ever in Rango. So when he’s not big-budgeting it, I always pay attention. And it looks like Verbinski’s going back to his roots with “Cure for Wellness” (currently in post-production). Verbinski wrote the script with Justin Haythe, who’s probably best known for penning the underrated Dicaprio/Winslet flick, Revolutionary Road. Let’s see what the two have in store for us today.

Writer: Justin Haythe (Story by Justin Haythe and Gore Verbinski)

Details: 118 pages – 2/17/15 draft

One of the hardest things to do in the horror genre is find a concept or location that hasn’t been used before. There are those who will tell you that everything has been done before so you shouldn’t even try. It’s best, according to them, to find a well-worn idea and put a new spin on it.

But I have a theory about writing. I call it “Hard vs. Easy.” Every writer makes a choice to write in either “Easy Mode” or “Hard Mode.” Easy Mode is when you turn off the analytical side of your brain and just write. You are not judgmental of your writing. You don’t go back and wonder if you could’ve done better. Whatever you put on the page is what you put on the page.

I call this “Easy Mode” because it doesn’t take any work. You write what you write and that’s it. “Hard Mode” is the opposite. In “Hard Mode,” you ask the tough questions like, “Have I seen this before?” And if you have, you go back to the drawing board and try to come up with a better choice. Hard Mode is hard because it’s not fluid. There’s a lot more stopping, a lot more thinking, a lot more judging. When you do come up with something, you have to rev yourself back up since you haven’t put anything on the page for awhile. Overall, it’s a much more taxing experience.

However, “hard mode” tends to provide better results because you’re nixing the clichés and obvious story choices that plague the majority of scripts out there. Writers who work on hard mode are more likely to find new locations, new ideas, new characters, because they just aren’t satisfied with the status quo. They know how vast their competition is and realize that the only way to compete with them is to challenge every idea they come up with.

A Cure for Wellness takes us to a place we’ve never been to before in a horror movie. That’s a “hard mode” choice. Sure, Verbinski and Haythe could’ve placed us in yet another mental institution. But we’ve seen that before. We’ve bought that t-shirt. Is it hard to nix that and spend a couple of weeks trying to come up with a location we HAVEN’T been to? Of course it is. But in the end it pays off because you’re giving the audience something ORIGINAL.

A Cure For Wellness introduces us to Castorp, a rising star at an unnamed company. Castor is the embodiment of the American upper-class male. He works 18 hours a day and is driven only by making more money and gaining more status than his fellow man. Castorp has no family, no friends, and defines his worth simply by how much business he can bring in for the company.

Right now, business is good. Castorp has been recognized by the board for his outstanding work. And they want to reward him. But first, they have a task for him. One of the board members, Roland Pembroke, went off to a “wellness” center in Switzerland and hasn’t come back. A big merger is coming up and Pembroke needs to sign off on a few things before the merger can happen.

Castorp isn’t happy, but anything that gets him further up the company ladder is a price he’s willing to pay. So off he goes to this remote wellness center, which happens to be in the mountains of Switzerland, one of the most beautiful places in the world.

Once there, Castorp realizes there’s something “off” about this place. While it’s state-of-the-art and all of the wellness clients seem happy, there’s a mysterious air about it all. Everyone always seems to be going off to their next “treatment,” and when they come back, there’s something a little less “there” about them. Oh Castorp, if you only knew how much worse it was going to get.

Castorp requests to see Pembroke at the manager’s office, but it’s past visiting hours, which means Castorp will need to wait until tomorrow. Castorp, personifying the impatient American businessman, demands to see Pembroke now. He’s eventually visited by the wellness center’s founder, Henrich Volmer. Volmer is a calming man, and assures Castorp that he’ll be able to see Pembroke soon.

A frustrated Castorp decides to head back into town while he waits, but ends up getting in a car accident. He wakes up three days later inside of, you guessed it, the wellness center, where Volmer informs him that his body is all out of whack. Volmer encourages Castorp to participate in his program, which, as you can imagine, takes Castorp down a rabbit hole he may never climb back up from.

Cure for Wellness invokes movies like The Wicker Man, The Shining, and Shutter Island, but manages to be something in and of itself. Its best asset is its irony. Here we have the world’s topmost “wellness” center, and yet as the story goes on, its clear that its patients are descending into an unrecoverable sickness.

As I pointed out in the beginning, Verbinski and Haythe committed to writing this on hard mode, allowing it to feel quite different from movies with similar setups. One of the creepiest (and more original) choices was the design behind the wellness “cure” for its patients, which was based around hydrotherapy. All of the treatments were designed around water.

You were placed in water, water was infused in you, you were asked to drink a certain water. And so there are a ton of creepy scenes that involve the innocuous fluid. One of my favorites was when Castorp was placed in a water tank not unlike the one Luke is placed in after getting injured in Empire Strikes Back. The techs responsible for him sneak off and engage in a weird sex game. In the meantime, two black eels appear inside the tank and Castorp starts freaking out, accidentally destroying the breathing apparatus, resulting in him losing consciousness, all while the techs are off in the other room, enjoying themselves.

Water tank therapy. Black eels. Tech operators engaging in freaky sex games. Can’t say I’ve ever seen THAT in a movie before. And that, my friends, is how you write on hard mode.

The only thing that worried me while I was reading Cure for Wellness was that it was going to be a “smoke and mirrors” screenplay. What’s that, you ask? “Smoke and mirrors” screenplays – which I see a lot of in the horror genre – are when the writer’s story is driven by a series of red herrings, twists, and half-baked mythology.

They’re essentially one giant sleight-of-hand, a desperate hope that you’re looking at the trick rather than what’s really happening. A good script has its mythology, backstory, and storyline figured out ahead of time so that everything comes together and makes sense at the end. Since horror is an inherently sloppy genre, with writers more focused on scares than story, you see a lot of smoke and mirrors. God forbid you actually do the hard work and make it all make sense.

There are people who feel that Shutter Island was a smoke and mirrors screenplay. There are people who think It Follows was a smoke and mirrors screenplay.

It’s particularly easy to go the smoke and mirrors route when you’re writing one of these “main character is going crazy… or is he???” scripts. The rationale is that because he doesn’t even know if he’s going crazy, we can be unclear about everything, leaving it “up to the reader” to decide what’s real or not. The problem is, when you leave EVERYTHING up to the reader, you prove that you haven’t figured anything out for yourself. Leaving your script feeling lazy and uninspired.

But I’m getting off-track. Cure for Wellness had so many weird things going on that I didn’t think it could bring itself back from the edge. However, the deep and rich backstory about the wellness org’s origins (which dated back 200 years), as well as the reveal of what Volmer did to all his patients –indeed came together in a satisfying way.

I get the feeling that this will be an even better movie than it is a script. It’s got a bit of a “blueprint” feel to it as opposed to a standalone script feel (like yesterday’s screenplay). I’m betting the trailer is going to look amazing. Good to see Verbinski recovering from Lone Ranger.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the things that drives me nuts when reading a script is when the writer preps us for the setting AND THEN FOLLOWS THAT BY GIVING US THE SETTING. Just give us the setting! Screenwriting is about conveying as much as possible in as few words as possible. Telling us you’re about to say something before you say it is a waste of time. Here’s an example from Cure For Wellness: “The Mercedes moves through an idyllic setting: rolling green lawns, terraced gardens where PATIENTS play shuttlecock, shuffle board, lawn boules. Others walk along well-trimmed pathways, through gardens with bountiful flowers.” The first part of that description is superfluous. We should grasp the “idyllic setting” when you describe the “rolling green lawns, terraced gardens, etc.” You don’t need to first tell us it’s an “idyllic setting.” I should point out that this is a personal preference thing. There is no “right” way to write. But writers who follow this rule tend to have smoother easier-to-read scripts.