Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Rom-Com

Premise (from writer): A woman with a rare auditory disorder reconsiders her life of solitude when she meets an inquisitive sound engineer (who might just be crazier than she is). But is his interest in her a case of romance…or research?

Why You Should Read (from writer): Did you love “A Beautiful Mind” with Russell Crowe and Jennifer Connelly? Did you secretly wish it had been more like Russell Crowe’s personal life – i.e. funnier, with less math and more assault charges? — If you answered ‘yes’ to both these questions then please consider casting your eyeballs over my RomCom, The Introvert’s Playlist. I’d be grateful for any and all feedback. I’ve already pledged my first born child to BifferSpice in return for his absolutely incredible notes, but if I wind up having twins you’re all welcome to fight over the other one I guess.

Writer: Rachel Woolley

Details: 94 pages

Rachel Woolly, thank you for making me a happy man. When I opened this and saw 95 pages after a full day of work, I praised you and the Dragon Gods of Screenplay Heaven. If I’d opened a script that was more than 110 pages, I don’t know if I would’ve made it to the end. Never, my screenwriting friends, NEVER underestimate the power of a low page count. It can IMMEDIATELY put the reader on your side.

It’s been a weird last couple of weeks with a shockingly low amount of industry news. Even Comic-Con was light on talk-worthy topics. One thing I’m noticing more and more is that I no longer have a go-to site for movie news. It used to be Deadline Hollywood when Nikki Finke was running the show. But now they’re just copying and pasting press releases to keep their feed going. I thought for sure Finke’s new site was going to fill this gap, but her posting has been scarce to say the least. Why did she even start a new site if she wasn’t going to post on it?

This has left me scrounging for tidbits from multiple sites (THR, Variety, Latino-Review, Slash-Film, First Showing, The Playlist, The Wrap). And still I feel like I’m not getting as much movie news as I desire. More and more, sites are dedicating their time to television, which is great. I cover television on Tuesdays as well. But movie news is still the reason I get up in the morning. I’d be curious to hear where you guys browse around. Maybe the ultimate movie news site is out there. Or maybe there’s an opportunity for somebody new to step up and fill the gap. It might even be you.

Okay, let’s clumsily segue into today’s first Rom-Com script in forever on Scriptshadow. Iris, 29, has a rare hearing disorder where simple noises (breathing, ticking, eating) become extremely loud in her head, to the point where it’s like 17 construction companies all decided to build the world’s tallest skyscraper inside of her brain at once.

Naturally, this has made Iris quite anti-social. In fact, she spends most of her time at home, where she can control the noise. But even that’s becoming difficult, as the next door neighbor’s dog is constantly barking his snout off.

As if God hasn’t made her life difficult enough, Iris gets pulled into Jury Duty for an assault case and must sit in a quiet court room all week where simple noises go to breed. The breathing, the coughing, the hacking, the shifting. It’s like bullet holes to her face.

Strangely enough, another audio-obssessed individual happens to be the defendant in the trial. 31 year old Levi is a professional sound recorder who ended up here for supposedly assaulting a ditzy 23 year old who enraged him when she ruined his recording (by taking selfies no less).

Iris is the only one not buying the girl’s story. And after a protracted argument with the other jury members, she finally convinces them to vote Levi innocent. After the trial, Levi finds Iris and wants to thank her for helping him out.

The two get to know each other, and Levi gets a first-class seat on Iris’s insane auditory life. All of Iris’s defense mechanisms are up and she tries to go back to Alonesville so she can live in her safe little bubble again. But wouldn’t you know it, Charming Levi convinces her that love is more important than anything, including annoying breathers.

As I read my way through the first 10 pages of Introvert’s Playlist, I was really impressed. I’d seen some of the comments on the Amateur Offerings post, and while most were praising the writing, many said there were big problems with the story.

Well that wasn’t the story I was reading. The writing here was confident and strong, highlighted with perfect “show don’t tell” scenarios about Iris’s unique disorder (dismantling the waiting room clock at the dentist’s office because it was ticking too loudly). Her writing was also that perfect combination of sparse, yet informative.

But then something happened. A switch was pulled. It’s important for every writer to know when they lose their reader – which story choice broke the suspension of disbelief camel’s back. Because without that knowledge, you can never truly fix your script.

It was page 12 when it happened for me. I had just learned a ton about this unique and intriguing auditory disorder. That alone gave me tons of confidence in the writing because normally when I read a script, the writer’s droning on about something I know EVERYTHING about because I’ve read 20 scripts about the exact same thing over the past month alone. This, however, was new and fresh and different. I was in!

Then we go into this ultra-silly jury case that felt like it was made up on the spot. Having a full 12 member jury for something as insignificant as a simple assault case felt false (especially since it was so clear that the girl was lying). And once that felt false, the introduction of this entire Levi-Iris relationship felt false. And since I had to buy into that relationship in order to buy into the rest of the script, this scene ensured that I wouldn’t get into the rest of the script.

I think writers forget this. That certain scenes in scripts are so critical, that if they don’t work, they ensure dozens of other scenes won’t work either. When you’re setting up your key relationship, even in a comedy, that’s a scene you have to get right. And an overly silly court case isn’t right. There’s no truth to that scene. And when the reader senses a lack of truth, they stop trusting you.

If I were Rachel, this whole court scene is the first thing I’d ditch. Figure out another way for these two to meet each other. Make it more natural. Make it honest. Because this moment is the infrastructure for everything that happens after it. I actually wondered why Rachel didn’t put Iris up in the mountains in place of Assault Girl. This seems like a place Iris would go (to escape the noise) and therefore a more natural place for her to run into Levi.

The other big issue I had was with Iris herself. And I sympathize with Rachel because I know the balancing act she was trying to pull off here. But whatever way you cut it, Iris is equal parts sympathetic and annoying. We feel for her because we know what she’s going through. But it’s kind of like the complainer girl in a group of friends, the one who’s always too cold and she lets you know it? The first time you hear her say it, you feel bad for her. The second time, less so. The third time, it’s a little annoying. The fourth time, really annoying. And after that you just want to strangle her.

There’s a little of that going on here. I feel bad for Iris’s situation, but there were times where I just wanted to say, “Get over it!” Every script has one big balancing act you have to pull off, and I think this is Playlist’s. You have to convince an audience to sympathize with someone who’s annoyed by something no one else finds annoying. Not an easy task.

Now with all that said, there’s some quality writing here and I do see some promise in the story itself. But it needs more truth. I say ditch the over-manufactured court stuff and tell a simpler story about a unique couple. Focus on exploring the characters, not some overcooked plot. I see this as more of an indie film due to the quirkiness of our heroes, so I’d play it more drama-comedy than comedy-drama. Somewhere in the tone of Lake Bell’s “In A World.” That’d be my advice on where to go. I wish Rachel the best of luck. ☺

Script link: The Introvert’s Playlist

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Despite my early rant about page count, page count should always be dictated by story. Several key factors will play a hand in whether your script should top out at 90 pages or 120 pages. The main two are genre and character. Fast and loose genres like Thrillers and Comedies will be around 100 pages. Thicker and more introspective genres like Period Pieces, Real Life Drama or book adaptations, can easily top out at 120. If your story has a high character count (Zero Dark 30), you’re going to need more room to fit them all in. And if you’re doing some major character exploration and/or character development (Silver Linings Playbook), you’re going to also need more pages. Then there are the miscellaneous things. Big world-building stuff (Guradians of the Galaxy) will need space, as will really elaborate plots (Burn After Reading, American Hustle). In the end, take in all this information and figure out if you need a lot of space to tell your story or not that much. Be honest with yourself, give yourself a page goal ahead of time, then try to hit it.

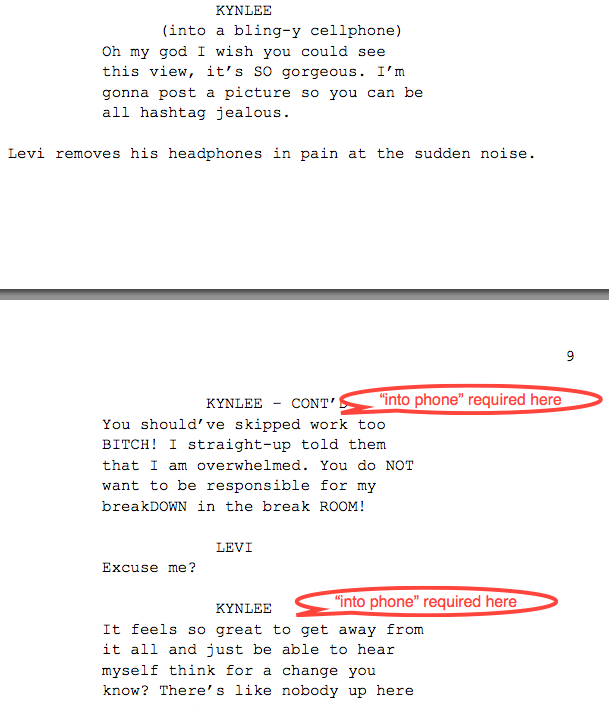

What I learned 2: Always put “INTO PHONE” (or “ON PHONE”) in parentheticals when a character is on the phone. Not just the first time they speak but on all of their phone dialogue lines. This is ESPECIALLY important if you’re intercutting a conversation with a third party. That’s where things start getting confusing for the reader. When Kynlee was on her phone AND having a separate conversation with Levi, I wasn’t clear who she was talking to. Here’s the first part of the exchange in question.

I recently read a script from a beginner scribe that wasn’t very good. The key problem was the plot, which was too simplistic and predictable. This simplicity bled into the scene-writing, which was also too predictable. Everything had an “obvious” quality to it, like the writer hadn’t considered any other possibilities. Frustrated, I shared the experience with Miss Scriptshadow, and we got to talking about it.

We came to an agreement that the reason the plot was so simplistic was because the writer wasn’t being discerning. He wasn’t thinking about what he was writing. He was just writing. This is both the blessing and the curse of being a beginner. A blessing because having no filter means total and utter euphoria when you write. Everything feels wonderful because you never have to think beyond your first inclination. And if it feels that good, then the writing must be good, right?

It isn’t until you’ve written a few scripts that you realize there are choices involved in writing – that it’s okay to stop and think about what you’re going to do before you do it. Because the curse side of never considering options is that your script reads option-less. The plot is either simply boring or simply messy, but it’s always simple.

Here’s the crazy thing though. I was reading another script later in the week – a professional script – and I was encountering the same problem. Not as frequently as with the beginning writer, but it was happening every fifth scene or so. I realized that it’s not just beginners who are guilty of this. The best writers in the world do it as well. It’s a slightly different variation of the practice, but it’s essentially the same thing. I call it: “Predisposed Writing.”

Predisposed Writing is when you go into a situation – usually a scene – knowing what you’re going to write beforehand. This may seem like a good thing. If you already know what you’re going to write, then it must be a good scene! What other explanation could there be for being so certain about something?

But if you already know what you’re going to write, chances are the reader’s going to know what you’re going to write as well. That means you’re writing a scene that they’ve already imagined. And if that happens, you’re boring them. Readers (and audience members) can be sympathetic to this for a scene or two. But if it keeps happening, boredom sets in, and they officially check out.

I’m not saying that your first inclination for a scene is always wrong. It may actually be brilliant. But you owe to yourself to STOP before you write a scene and think about other options. Chances are, there’s something better in the cupboard.

Let’s try to look at this visually. I want you to pretend that you’re an interior designer and imagine you’ve just walked into an empty room, a room which you’ll be designing.

A bad (or beginning) interior designer is going to go into this room with a predisposed point-of-view. They know what a basic room looks like. So that’s what they’re going to give the client. A TV near the corner by the cable outlet. We’ll throw the couch back against the wall. Maybe a vase by the TV to make it look nicer. A lamp or two. In your head, you’re imagining this is going to look pretty killer. Then, when you put it together, you get something like this…

Now you’re looking at this room and probably saying, “Oh my GOD. I would kill myself if I had to live in that space!” Well folks, you’re looking at the visual equivalent of 90% of the scenes I read in amateur screenplays. They’re that dull, that lifeless, that devoid of creativity, and it boils down to writers being too set in their ways.

A good interior designer’s first step is to let their initial inclinations wash over them. Not ignore them. They may still use them. But first they want to explore some not-so-obvious choices. Maybe a nontraditional couch as the centerpiece. A cowhide rug instead of a boring hardwood floor. How does the light come in from the windows? Is there any way to arrange the room to accentuate that? With this approach, you’re more likely to get something like this…

Notice how much more thought was put into this room. Notice how they went with a hardwood floor AND a rug. Look at how the rug is shaped. Look at how funky the couch is. Look at the unique shelves placed on the wall. The other designer didn’t even put shelves on the wall. This room is infinitely nicer than the one above.

Now I can already hear some of you crying foul. “That’s cheating, Carson. The second room has a floor-to-ceiling window and costs a hundred times as much to furnish.” I admit that the analogy breaks down a little in that sense, but not really. With writing, the only currency is time. You have no budgetary considerations. If you take the time to challenge yourself and flesh out your ideas, you can create windows with the most beautiful views in the world. You can put a 20,000 dollar couch in your room. You can change the walls to brick. An imagination is infinite, and when you predispose your writing, you prevent yourself from mining all those possibilities.

Predisposed Writing is not just a scene thing. Writers come in with predisposed characters. They come in with predisposed relationships. They come in with predisposed concepts. The thing to remember with writing, especially screenwriting, is that nothing is set in stone. You can have an idea for something, but once you’re tasked with putting that “something” down on paper, it’s your job to challenge it. Your mind, more or less, has been trained by society to think and act like other minds. Which means most of what you come up with is the same kind of stuff other people come up with. Going against your predisposition, then, is the only surefire way to provide a unique experience for the audience.

Let’s apply this practice to an actual scene, shall we? Let’s say we’re going to write one of the more common scenes in screenwriting, a cop arresting someone, let’s say a drug dealer. Now you’re probably already imagining how this scene is going to play out, right?

My predisposed version has a sketchy dealer on a street corner in a bad neighborhood, dealing dope to some loser. Our officers pull up their car, pop out. The Dealer ushers the buyer away, turns to our officers as they’re approaching, an innocent smile at the ready. Looks like this isn’t the first time they’ve met. There’ll be some funny “we’ve been through this before” banter between the three. But the Dealer senses that something’s off, that they might actually arrest him this time. He decides to make a run for it. They chase him down. Catch him. Scene over.

Hmm, how many times have we seen that before? It might as well be in the Predisposed Hall of Fame. So let’s see what happens when we spend some time considering other options. Again, there’s no law that says you have to write these options into your script. All you’re doing is considering them.

A dope dealer in a bad neighborhood is cliché, right? So what if we made our dealer a… grand piano salesman who deals dope on the side? Our cops have evidence he’s dealing so they go to the piano store to arrest him. Inside, a child prodigy is loudly playing Beethoven’s 9th on a nearby piano. Our cops attempt to ask the salesman a few questions (or read him his Miranda Rights), but the annoying prodigy is playing louder and louder (secretly cued by the salesman?), resulting in a lot of “I’m sorry, I can’t hear yous.” In a moment of distraction, the salesman slams the piano flap down on one of the cop’s hands and makes a run for it. The prodigy breaks into some chase music.

This may or may not be the best scene ever. I’d certainly want to take it through a few more drafts, but it’s more inventive and less cliché than the previous scene.

Now obviously I’m writing with free rein here. Within the context of your story, your dealer may have to be on the street. That’s fine. Then you simply ask what other ways you can make the scene different. Maybe the dealer only speaks Spanish, creating a translation problem. Maybe the dealer’s the brother of one of the cops, complicating the arrest. The options are limitless, but they’re only there if you search for them.

In closing, all I ask is that you not get wrapped up in any predisposed notions when you write. Always consider other possibilities. I promise you that if you perfect this practice, you’ll become a much better screenwriter.

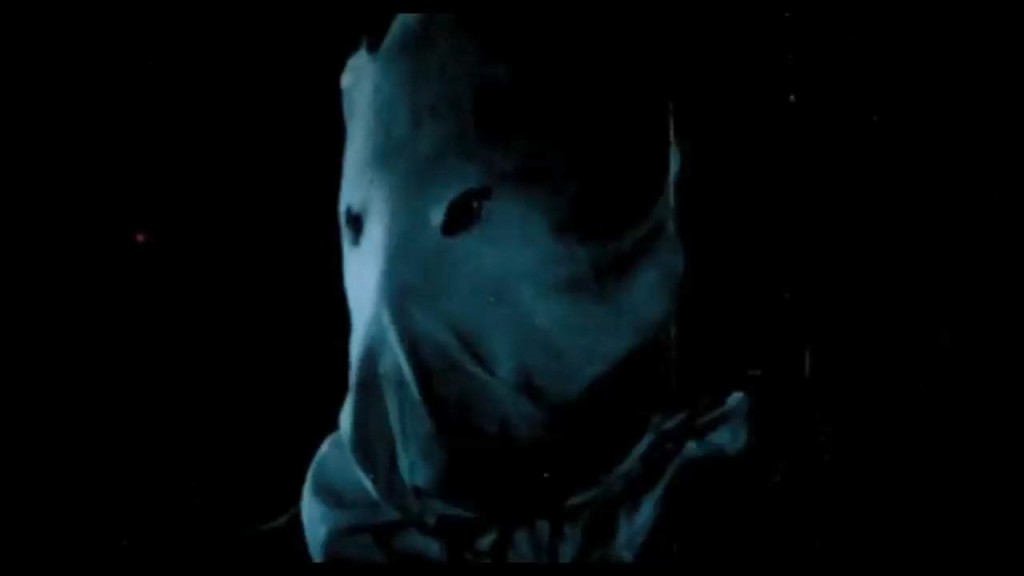

Genre: Horror

Premise: A long-forgotten killer from the 1940s reappears in the present day to wreak havoc on a small town.

About: Blumhouse ain’t stopping any time soon. The business savvy Jason Blum realized that we haven’t created an iconic slasher movie monster since the 80s. And why wouldn’t you, seeing as you can milk over a dozen movies from a memorable antagonist. “Sundown” is written by Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa, who scripted the remake of Carrie, and has also written on the TV shows “Glee,” and “Big Love.” The film will be directed by Alfonso Gomez-Rejon, who directed some episodes of American Horror Story, as well as Black List script, “Me & Earl & the Dying Girl” (cancer is in, baby! Producer: “I love it. When the hero saves the girl from the terrorists in the end? One of the best climaxes I’ve seen all year. Buuuu-ttttt, is there any way we can add more chemotherapy?”). In classic Blum fashion, the movie will star a bunch of unknowns. ☺

Writer: Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa (inspired by the film by Charles B. Pierce)

Details: 100 pages (2/25/2013 draft)

Don’t know much about this one other than that it’s a Blumhouse Production. Typically, I don’t review horror scripts unless they’re for Amateur Friday (where a lot of them seem to win the slot). But since Blumhouse so rarely misreads the public, it’s important, if you’re writing horror, to pay attention to whatever this guy does. Cause whatever he’s doing is setting the trend. Until someone else comes along at least.

Get your note pads out, because “Sundown” has one of the more needlessly complicated setups I’ve read in a screenplay. The story takes place in a town called Texarkana, which is a “double town,” split on the border between Texas and Arkansas.

Over half a century ago, in 1946, there was a series of horrific murders by a serial killer who wore a bag over his head. The man, who was never caught, was dubbed the “The Phantom Killer.” Flash-forward 30 years, and they made a movie about the murders, which became a cult hit. Now, every year in Texarkana, they show the movie all over town so people can freak out about their town’s very own ancient serial killer.

We’ll put an asterisk by “ancient” because it’s now present day. And when two teenagers, Cory and Jami, drive to a secluded area to do what kids in cars driving to secluded areas do, they see a man standing by the car WITH A BAG ON HIS HEAD!

We’re not sure if this is in protest to the new Los Angeles law that requires you to buy paper bags for your groceries or not. But whatever the motive, the bagged one pins Cory down and rapes him while repeatedly stabbing him. He makes Jami turn away, so neither she, nor we, can see what’s happening. But we can hear it. And our surly imagination is much worse than whatever’s happening behind this chick’s face.

While Cory doesn’t make it, Jami is somehow able to escape the killer, and the next day, the town goes into full-on Freak Out Mode. Is this a copycat killer performing a one-night thrill kill? Or is The Phantom Killer back!? And if so, how is he back? He’d be, like, 90 years old by now. Is he going to kill people with his acid reflux?

Long story short, our killer keeps on killing while Jami becomes a little investigator, researching all the murders dating back to that first fateful kill. As she slowly puts the puzzle pieces together, she thinks she knows who the killer is. But is it too late? The killer may have one last big kill in him before going into hibernation for another 70 years.

The Town That Dreaded Sundown should’ve been dreading its overly elaborate setup. There is a lot of information given to us in the first act that could’ve easily been summarized as “the killer’s back.”

A serial killer in the 1940s. A movie about those killings 30 years later. A complicated border town with two mayors. All that stuff would’ve been cool IF IT ACTUALLY MATTERED. But if you never mentioned any of it, we’d still know exactly what was going on. Psycho Freak who’s pissed about the paper bag grocery law is killing people and he needs to be stopped. 1940 doesn’t need to tell me that.

The irony is that once you get past that first act of exposition, the story becomes blazingly simple. A slasher is killing people. Our hero is trying to figure out who he is. Which meant for the next 50 pages, I was consistently 30 pages ahead of the writer.

Here’s the thing. Horror movies are all the same. They’re broken down into a few different categories (slasher, ghost, monster-in-a-box), but once you know which one you’re watching, the movie becomes incredibly predictable.

For that reason, you want to take whatever’s unique about your idea, and infuse that into the plot as much as possible, since that’s the only opportunity you have for making your script different. If your horror movie takes place on a pig farm, for example, I better not see a garden variety slasher flick. I should see horror where pigs are involved in various ways.

So here, I kept waiting for this double-town thing to work its way into the plot. Or this 1940s stuff. And the 1940s stuff does peek in every once in awhile. Maybe, for instance, the killer could be the son of the original #1 suspect in the killings. But in the end, nothing surfaced from that first year that affected the plot. It was still a killer with a bag trying to kill people.

Why not create friction between the border towns to begin with? And then this serial killing thing starts and each mayor has a completely different idea on how to tackle the problem. This causes a lot of conflict between the mayors and the towns. Maybe one of the towns is poorer, so the assumption from the richer town is that the killer must be from the “degenerate” side of the tracks.

You know what, if you really wanted to add some tension, why not set this on the border between the U.S. and Mexico. Now you can really explore some crazy shit.

As far as the 1940s stuff, I’m not sure placing the original killings in the 40s was the best thing for the movie. It’s too far in the past for us to believe that the same killer could return. If you changed the original murders to the late 1970s, now it’s conceivable that the original killer could be back. Again, 1940s sounds cool cause it’s so long ago but you can’t put “cool” things in your script if they don’t serve the story in an interesting way. Every choice you make must serve the story.

That’s not to say “Sundown” was bad. It had some really good scenes. The early scene with Corey getting raped while we stayed on Jami’s horrified face, looking in the other direction, imagining what was happening behind her – that was good stuff.

One of the most important things about being a horror writer is knowing when to show something and when not to. Sometimes, not showing is infinitely scarier. I’d go so far as to say that every scary moment in your script – you should consider both options. Should you show the horror or not? Your first inclination may be to show it. But always consider the alternative. It might surprise you.

“Sundown” isn’t breaking any new ground, which is a shame, because it could’ve. It had such an information-heavy setup that I was sure all this information was going to be used to create an elaborate horror plot that I’d never seen before. Instead I got “Halloween” but with a not-as-cool mask. Not a bad script. But not that good either.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Very important for writers to know. If you’re writing 5 line paragraphs or longer, the reader is skimming through those paragraphs. Lots of writers laugh in the face of the “stay under 4 lines” rule of writing action paragraphs. But readers HATE huge chunky paragraphs and they take it as an insult when you write them. They fight back by skimming. To prevent this from happening, keep your paragraphs short!

Genre: Period Drama

Premise: Set in the 1700s, Knifeman chronicles the birth of modern surgery.

About: Knifeman is one of the lucky pilots that survived AMC’s in-house contest where only the best pilots, as voted for by the employees, make it to air. Knifeman is written by Rolin Jones, who created another AMC series, Low Winter Sun, which didn’t make it past the first season. Rolin has also written for Friday Night Lights, Weeds, and the United States of Tara.

Writer: Rolin Jones (created by Ron Fitzgerald and Rolin Jones) (Inspired by the book, “The Knife Man: Blood, Body-snatching, and the Birth of Modern Surgery” by Wendy Moore)

Details: 50 pages (AMC CUT #3, 12-16-13 draft)

We’re reaching a new era in television that I suppose was inevitable. So many damn channels are getting into original programming that the supply is usurping the demand. Shows are paying more and more to advertise their arrival but their premiers come and go without a whisper. Someone told me The Strain debuted a few weeks ago. I had no idea. “Salem?” A pilot I reviewed a while back. I guess that’s had an entire season already? You could’ve fooled me.

It seems like there are 5 “buzz-worthy” shows on TV at any one time and if you’re not one of those shows, nobody cares about you. Those shows, at the moment, appear to be Game of Thrones, The Walking Dead, Orange is the New Black, Scandal, and The Good Wife.

As for why I picked Knifeman today, it’s because AMC cares more about its scripts than any other network besides HBO. So even though I don’t have much interest in 18th century surgery, I knew the script was going to at least be interesting. And it was.

It’s the 18th century and a bad time to be a human being. You get a head cold on Wednesday, you could be picking out your burial plot by Saturday. But you know, doctors are still doing their thing. They’re selling patients on the equivalent of frog blood, but the patients don’t know any better, so everyone goes along with it.

In this medical mediocrity, we follow two doctors. One is Julian Tattersal. He’s an esteemed doctor/surgeon at St. Stephen’s Hospital. Then there’s his brother, John Tattersal. John is technically a barber. But in his spare time, he jacks recently deceased bodies from the local cemetery, cuts them open, and explores the human anatomy, looking for new ways to perform surgery and save people.

John is desperate to get in on this whole St. Stephen’s gig, but for some reason, his brother Julian looks down on him, and refuses to help him get a job. Ya see? Nepotism doesn’t always pay off.

Eventually, the two find themselves fighting for the same client, a man who’s accumulated a nasty blood clot on the back of his leg. Julian says the only way to help him is to amputate the leg. John disagrees. He says he can get in there, tie off the artery, and the circulation will move around the problem spot. No amputation needed.

Even though John is very unofficial, the man chooses him because he wants to save his leg. The finale is the big operation, and – spoiler alert – everything seems to go well until John is finished, when the artery is tied up and the man drops dead. The end.

I’m far from understanding TV pilots as well as I do features, but I know enough to say that Knifeman does not deliver on the pilot front. First of all, the show feels way too small. If you look at a previous AMC pilot, Turn, there’s a bigger overarching storyline about the United States trying to gain independence. It added stakes and urgency to the more personal storylines that the characters were engaged in.

There’s none of that here. This literally has only two storylines. Julian doing work at the hospital and John doing work in his apartment. It’s way too simple and way too general.

You also need a series of hooks in a TV show, whether those hooks are teasing the segment after the commercial break, teasing the next episode, or teasing the entire series. Give us a giant monster walking through the trees (Lost). Give us a potentially deadly cancer diagnosis (Breaking Bad). Give us a sister who was supposedly abducted by aliens (The X-Files). There weren’t any hooks teasing anything here, so I rarely found myself interested in what was going to happen next.

For example, the end of the pilot (spoilers) has John killing this guy during surgery. And that’s it. Where’s the reason to watch the next episode if the question’s already been answered (he’s dead – oops)? We certainly don’t get the sense that killing this man is going to put John in danger. He made it clear to the man (a servant) and the man’s owner that he could die during the surgery.

And that was another thing about this that made it small. There were no stakes! I mean why is John working on a servant? Someone whose life doesn’t mean anything?? If he dies, so what? Why couldn’t it have been someone of importance in the town? Now there’s some real shit on the line. If John fails, his career is over before it starts. If he succeeds, he’ll be a superstar. But no, it’s just a nobody who nobody cares about. And that seemed to be the theme throughout. If there was a choice between making something big and important or small and insignificant, the latter was chosen.

What I was hoping for was that, as both John and Julian worked their way through the surgeries, they’d start noticing some spooky unknown disease inside the bodies, perhaps the start of a plague. And they realized they weren’t equipped to deal with this problem if it spread. That’s the kind of long-standing “problem” or “hook” I was seeking from this episode but never got it.

Honestly, I don’t know where this show goes from here. I don’t know what the episodes are going to be about. A pilot’s supposed to bring up a lot of questions that we want answered. But the only real question seems to be whether John will become an official doctor at the hospital. I’m not sure I care enough about that to keep watching.

The only time the script really came alive was during the surgeries, when the gooey bits of human flesh oozing and pumping inside the bodies were bandied about. I started to wonder – is the only reason they made this show so they could show gross surgeries? They wouldn’t make an entire show just to show that, would they? And yet blood and guts were the big star here.

With all that said, I do see the potential of this world. There’s something weird and unsettling about the imagery in Knifeman. A hack of a barber doing stolen cadaver surgery in his dark apartment, surrounded by jars of brains and hearts and livers – that’s something you can build a show off of.

They just haven’t created a story yet. You need more than incisions to keep people tuning in every week. If they figure that out, Knifeman is going to be a nice offbeat alternative to the bigger shows on television. If not, it’s going to end up like a botched surgery on E.R.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It’s risky if the only thing going on in your TV show is the immediate on-screen stuff. It’s better if there’s a bigger overarching storyline or problem to give the show some gravitas. The big mistake here was that Knifeman was only about these two surgeons and nothing more. It needed something with some scope that hinted at a bigger story. If we feel a show is too small in scope, we have a hard time seeing it last.

Genre: Superhero!

Premise: An Amazonian Princess living on a remote island is brought to the real world, where she uses her unique set of powers to take down a mega-corporation with world domination on the brain (basically every comic-hero plot ever).

About: This is the Joss Whedon draft of Wonder Woman he wrote in 2006! Whedon, as many of you know, has left his DC buddies in the dust to become the head directing honcho of Marvel Universe with his Avengers films. To give you some context of the movie business when Whedon wrote this, the two big superhero films preceding this draft were 2005’s Batman Begins and 2004’s Spider-Man 2. Both films were considered dark (Batman moreso than Spider-Man of course) and so the dark realistic super-hero trend was beginning.

Writer: Joss Whedon

Details: 115 pages (2006 draft)

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Yay!!! Michael Bay is a kajillionaire. Can’t say I ever got into the whole mutant turtle thing. But I knew when Dr. Explosion decided to put his particular brand of vapidness on the turtle tale, I definitely wanted nothing to do with it.

I was rooting for Swetnam’s Into the Storm (spec script) to do some hurricane like damage at the box office, but it just goes to show how difficult it is to play with established properties (remember that spec script writers – it’s why your concept has to be really awesome for Hollywood to take notice). Into the Storm needed at least a couple of recognizable faces to sell the movie, like Twister and The Perfect Storm before it. I don’t think a storm by itself can do all the heavy box office lifting.

Speaking of storms, what happens when a Marvelnado and a DCunami meet? You’ll find out today. Whedon, the flagship director for the third biggest movie ever, Marvel’s Avengers, wasn’t always chummy chummy with the Marvel comic book family. He was once playing for the other team, scripting the DC script for Wonder Woman.

Stories like this always intrigue me. Because if Joss Whedon wrote a Wonder Woman script today, while he’s on top of the world with the biggest franchise in the world, everyone would be DESPERATE to read it. It would be the hottest script in town, right? So what changes if he wrote it eight years ago? Was Joss Whedon any worse of a writer? He may not have been a household name at the time, but he’s still the same guy. So why not use this script for a wonder woman movie. Say it’s written by Joss Whedon and everyone wins, right?

Well, that’s assuming he overcame the same problems everyone who’s been trying to adapt Wonder Woman over the decades has run into. Which is that her character’s not fit for today’s super hero audience. A lasso that makes people tell the truth? How dumb is that? It looks to me like they finally said fuck it and Zack Snyder is going to change the character to make her a straight-forward ass-kicking female, kind of like how he dropped the whole Clark Kent glasses reporter stuff. Screw history.

But what if Joss Whedon had been in charge. What would he have done? Let’s find out!

I don’t know if you knew this or not. But Wonder Woman is an Amazon. You know that legendary island full of tall beautiful ass-kicking ladies? Well it’s real. At least in this script it is. A pilot named Steve is bringing food and supplies to child refugees when his plane goes down and crash-lands on this Amazonian Island.

At first Steve goes looking for Jeff Bezos, but he ends up running into Diana instead. Diana is the Princess of the island. And when her mother, the queen, finds out that a man has entered the perimeter – a huge no-no on this island – she sentences him to death! (probably why Beznos is hiding)

But Diana’s developed a little bit of a crush on Steve, and challenges her mom to a duel for the right to help Steve get off this island and save the children! She ends up winning, and the two head off, where Diana learns the complicated multitudes of the real world, namely that when you deliver supplies to kids, a local warlord is going to want 75% of the goods for himself.

After the Warlord shoots Diana for questioning his motives, she gives him a taste of his own medicine, beating some ass, and Steve realizes he’s got something special here. So he takes Alice/Wonder Woman back to the U.S., to a crime-ridden city called Gateway, which I guess is Wonder Woman’s version of Gotham.

In Gateway, there’s this super-huge company called Spearhead that poses as a wonderful company that manufactures weapons to help the United States defend itself.

Wonder Woman, pissed that there’s so much lying and corruption in this city, takes it upon herself to work her way up the local gangster ladder to find out who’s ultimately responsible for all this crime. Using her truth lasso (which forces people to tell the truth), it eventually leads back to, you guessed it, Spearhead.

The problem is, Spearhead’s being protected by a super-human of its own, some freaky-faced metallic skull-capped dude named Strife who, oh yeah, just happens to be the nephew of Ares. Ares as in THE GOD OF WAR! Yup, craziness is happening all over. So if Wonder Woman is going to save the day, she’s basically going to have to defeat a God to do it.

I’m going to give Whedon this. He somehow made Wonder Woman cool. I thought there was no way around the whole truth-lasso thing. But Whedon doesn’t use it much, and when he does, it’s with attitude (for example, with one gangster, Wonder Woman slings the rope around his neck like an Indiana Jones whip, before asking him who he works for).

But the biggest reason this worked was that Whedon went all in. He committed to this character, to this world, to the rules of this universe. And I think that’s what you have to do with these scripts.

When amateur writers tackle comic material, they typically have a vague sense of the hero they liked growing up, then they use their own imagination to fill in the gaps, whether it be their heroine taking down a gangster or kicking ass in some big set piece fight. It all feels very thin, like a writer who really loves movies including all his favorite movie moments in one script.

When you read the opening of Wonder Woman, the detail involved in this Amazon tribe, where they came from, the hierarchy, the connections between the characters. It feels like Whedon really immersed himself in the comics and knew this world before he wrote anything. And when you do that, even if the world is silly and weird, the audience believes it, because you, the writer, have committed to it.

That’s one of the biggest differences I see between amateur and pro writers. Pros commit themselves to the world. Amateurs learn a little bit here, a little bit there, and think that’s enough.

I never really knew how good of a writer Joss Whedon was until this script actually. His writing always seems to have this immediacy, yet it never feels rushed. It creates this propelling motion as you’re reading, spinning you down from one paragraph to the next.

In amateur screenplays, it always feels like the writer is fighting his sentences, writing himself into corners he must clumsily write himself out of.

And I noticed that what Whedon is really good at, is that no matter how intense things get, he’s not afraid to undercut it with a joke to lighten the mood. For example, near the middle of the script, amongst a lot of chaos, a girl stops Wonder Woman and with giant puppy dog eyes says, “My cat’s stuck up in the tree.” Wonder Woman looks up at the cat, then back to the girl. “Climb it.” She then runs off. This is something Christopher Nolan can learn from the Firefly scribe.

The only weakness in the script is that no matter how skilled Whedon is, he can never get too far away from the fact that this is a super-hero movie. There are only so many surprises you can pull on the audience. It’s why I liked X-Men: First Class so much. Because for once, there was something different going on that we weren’t used to in the comic book world. It’s why Batman Begins made such a big splash when it came out. Because it approached the superhero genre from such a realistic place (Nolan’s got Whedon there). It’s why, I believe, Guardians of the Galaxy did so well. Because these weren’t your typical super-heroes and it wasn’t your typical super-hero movie.

Those movies found little black holes to slip into that took them to parallel universes which allowed them to tell a new story. But Wonder Woman is stuck in the land of garden-variety comic book movies. It tries to break out (the first act, away from the city, felt pretty unique), but ultimately is pulled back in (giant egomaniacal city villain alert).

I’m actually shocked that audiences haven’t grown tired of the genre yet because, like Wonder Woman here, we’re basically seeing the same movie over and over again. So kudos to Whedon for writing what really is a cool script. It’s just too bad he was limited by the genre.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In fight scenes, it’s not as important to detail every punch or sword swing, as it is to give the reader a sense of what kind of fight it is. Tell us how each fighter fights, and we’ll be able to fill in the visual gaps ourselves. So when Wonder Woman fights her mother, Whedon writes: “Everywhere Diana strikes, Hippolyte counters. Diana tries to control the fight through youth and relentless strength, and though she responds with no less, Hippolyte relies on experience over enthusiasm.” Obviously, you’ll detail fight specifics after this, but sentences like this allow you to summarize pieces of the fight so you don’t have to detail. Every. Single. Swing.