It’s one of the biggest breaking scandals in the history of civilized society. But the real question is, can I stay civilized when breaking down this screenplay?

Genre: Drama/True Story

Premise: The story of how a group of reporters at the Boston Globe exposed the Catholic Church pedophile scandal.

About: Can the man who directed “The Cobbler” direct an Oscar-winning film? That’s the question of the day since Tom McCarthy co-wrote and directed “Spotlight” after the Adam Sandler Netflix classic. Josh Singer co-wrote the film with McCarthy. Singer’s resume includes stints on The West Wing and Fringe, with his lone feature credit being about international narcissist Julian Assange. Spotlight is peppered with a cast that makes my man-panties drop. Mark Ruffalo, Michael Keaton, Liv Schreiber, Rachel McAdams, Billy Crudup, Stanley Tucci. I just want to lick those names, they look so yummy. You can lick them too, on November 6th.

Writers: Josh Singer & Tom McCarthy

Details: June 5th, 2013 draft (132 pages)

I suppose it’s appropriate that we’re warming up for Oscar season since it was freaking 99 DEGREES OUT TODAY. Dammit-to-Tinley-Park. Holy hell. I’ve seen cooler days inside of a Chicago pizza oven.

Despite the heat, I’m always lukewarm this time of year. Because let’s be honest. Half the Oscar wannabes believe the key to getting nominated is to put a bunch of serious-looking men in rooms talking about serious things.

They forget that the number 1 ingredient to a good movie is to ENTERTAIN. I’m reminded of Zero Dark Thirty a couple of years back. It was the prototypical, “Serious-looking men in rooms talking about serious things” film. I’m not sure anybody working on that film ever asked, “Hey, do you think people are going to enjoy this?”

And Spotlight is the prototype for “Serious men talking about serious things” films. I ain’t hatin on you, Spotlight. But dude. You gonna need to add some color to your wardrobe if you want audiences to let you into their apartment.

Whether you have a noble message or not, nobody cares unless they’re entertained. Let’s see how well Spotlight achieves this.

Spotlight’s fifteen thousand protagonists are led by two in particular, Mike and Robby. The two worked for the Boston Globe back in 2001, and start investigating a rumor that there are pedophile priests in the Catholic Church.

Their research is encouraged by the Globe’s new editor, Marty Baron, a Jewish man who just took over the job from a stalwart Catholic.

Mike and Robby are joined by many other journalists including Matty and Sacha and Ben. Our only hope of remembering who’s who lies in the fact that Sacha is a woman. That leaves us with a fighting chance to distinguish the remaining four.

Through his research, Mike finds out a local lawyer used to help the church settle a lot of pedophilia matters behind closed doors – as in, the state wasn’t even involved. This was the first sign to Mike that something big was up.

After putting out some feelers, Mike learns that priests raping children isn’t the only part of this scandal. It turns out the head of the Catholic Church KNEW this was going on, and actively created a system to deal with these matters, which amounted to sending the offending priests to other churches, where they would just abuse more boys.

Mike’s main challenge is to find the public record that will ‘smoking gun’ this story. Because if it’s just a bunch of conjecture, the church will say it’s a lie and the nation will believe them. You have to remember, they have the man who created the universe on their side. That’s pretty persuasive.

Somehow, Mike finds out about a lone public record file that confirms everything. The question is, can he get it before the church finds it first? Because if he doesn’t, the story is dead and gone forever.

While reading Spotlight, I found myself asking a very specific question: “Can a great story survive bad writing?” Because this scandal is, without question, a great story. You have a gigantic institution covering up a huge scandal. You have hypocrisy on the highest level. You have thousands of child victims. This kind of story writes itself.

Unless, that is, the writing is so bad that the amazing story gets buried. And that’s what happened here. I don’t even know where to begin. I guess we’ll start with the character count.

There were probably 60 characters introduced in this script. That’s 1 every 2 pages. This made it impossible to keep track of what was going on. Our characters would be flabbergasted on page 60 by the actions of a character that hadn’t been mentioned since page 15. Every time a name came up, you were saying, “Wait, who is that again?”

And I get that this isn’t a problem onscreen when you can see faces. But the laziness in which characters were introduced here was so bad, it felt like they weren’t even trying. Robby, for example, is introduced in a bland setting with the description: He’s a “Boston everyman.” WTF DOES THAT MEAN? How does that tell me ANYTHING about who he is?? I didn’t even know he was a reporter until I saw him working at the Globe 20 pages later.

Mike was introduced the same way. His big introductory scene is walking into a slummy apartment. What is this supposed to mean, exactly?? What does this tell me about Mike?? I didn’t know if Mike was an out-of-towner who just moved into this apartment, if he’d been kicked out of his house by his wife and had to stay here in the meantime. I didn’t know what he did for a living.

That’s what really bothered me. When you write characters, good writers know that the first thing you do – ESPECIALLY in a script with a ton of characters where it’s easy for the reader to get lost – is to introduce that character in a setting that tells us WHO THEY ARE. Look at how Jules and Vincent are introduced in Pulp Fiction. You know exactly what those characters do and who they are after that first scene.

There wasn’t even the tiniest attempt to clue us into who these people were when we met them. This forced me to make educated guesses throughout and only later put the pieces together on who this person was in relation to the story, well after key plot points regarding that character were mentioned, forcing me to mentally rewind and try to remember what those plot points were, now that I knew they were relevant.

Ironically, introducing any characters here was pointless. Because there are no characters in Spotlight. Oh sure, there are people who are pulling us through the story, but there are no CHARACTERS. Spotlight is one big investigation where we don’t know the difference between ANYONE.

I couldn’t mention one quality that was different between Mike and Robby. They were the same person – two reporters investigating a story. This extended to all the characters throughout Spotlight. They were all bland automatons trying to get a story for the Globe.

Why is this a big deal? Well, one, we don’t care about people we don’t know anything about. But the thing with character is, the more you know about a person, the more you can use that to connect plot and character.

For example, why don’t we have a single reporter here who is a diehard member of the Catholic Church??? That would’ve made them infinitely more interesting. Of course a character with no connection to the church is going to go after it. But if a reporter had, for example, an extremely religious wife? If their family went to church every Sunday? That person is going to be much more conflicted when it comes to investigating this story. That’s how you connect character and plot. But no attempts like that were ever made here.

And believe me, they had plenty of opportunities. The new editor of the Globe is Jewish. That was ripe for all sorts of conflict. Do the hardcore Catholics point to this editor as having an agenda? Do they pin all these accusations on that agenda? Does that begin to test the investigation? Does the editor start to back off as a result?

No. We don’t get anything like that. In fact, there is so little conflict in a story that might be the most conflict-filled of the past 20 years, you wonder if McCarthy even knows what conflict is.

There’s not even a real villain here. There’s this guy Cardinal Law, who’s mentioned a lot and who we see briefly a few times. But it’s always from afar. This guy could’ve infused this story with a shot of heroin if he started pressuring the paper to back off. We get none of that!

Why didn’t someone from the paper have a child who went to church? Who was directly in the line of fire. It’s as if the church and the paper lived on two completely different planets. Which was SO the wrong approach to take here. Connect your damn stories. Create more complexity between your elements. Why is this investigation so easy for everyone doing it???????

I don’t know how this movie’s going to play out at the box office. The real life story it’s based on is so good that I’m sure people will want to see it. I just think you’re going to have audiences leaving this film and feeling empty, not because it isn’t delivering an important message, but because after you leave the theater, you’ll realize you never knew a single character in the film.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Find something everybody hates, then give us the worst version of that for your antagonist. You know something everyone hates? Bullies. “Spotlight” puts the spotlight on the biggest bully you can imagine, the Catholic Church – an institution that allows its employees to rape your children and then cover it up. No matter which way you look at it, that’s going to get people riled up and wanting to see that antagonist go down. And beyond making your hero succeed, that’s the other side of the equation you want to get right – making sure the audience wants to see your antagonist go down.

I’m out of the office today but a quick reminder that I’ll be informing everyone who made the Scriptshadow 250 on October 3! That’s a Saturday. Hopefully this will prevent all of you from pulling any more hair out. In the meantime, today is a good old-fashioned “test your logline” post. Feel free to ask for Scriptshadow Nation’s feedback on a concept, a few pages of your script, or anything else you want help with. And dammit, don’t forget to enjoy your weekend!

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Horror

Premise (from writer): A strange old man tells scary campfire stories to two young boys. But who is the man, why are the boys in the stories and where are their parents?

Why You Should Read (from writer): Early in the year, you wrote a couple of posts, the gist being – You want to stand out in the current spec market? You need to take risks. So, I sucked up that advice, threw caution to the wind and the result is this very different little horror script. It takes the sort of structural and narrative risks I normally wouldn’t.

Writer: Ashley Sanders

Details: 86 pages

Atmosphere.

Every horror film needs it.

But how much atmosphere is too much?

The most atmospheric horror movie of all time is probably Suspiria. Story is placed on the back burner in favor of terrifying imagery and eerie music. And it works like cheese on tacos. You don’t forget that movie after you’ve seen it.

Which I’m guessing was Ashley’s inspiration here. She says in her WYSR that she wanted to move away from convention. As long as you have a solid understanding of storytelling, I encourage this.

But what I often find happens to a writer going off on one of these “experimental” journeys is that they embrace the “fuck it” attitude a little too excitedly. It’s as if they think NOTHING should make sense, less the script fall back into the dreaded “c” word (convention).

But even when you’re writing something different, you still need to follow some rules. Just like if you wanted to build a house that nobody’s built before, there are still some common things you’ll need to add – like walls.

Small Slices walked that line a little too liberally and while there’s some good stuff here, I’m not sure there are enough walls to keep it from falling down.

The script takes place in a forest at night, with a man known simply as “the storyteller” telling two brothers, Mark (7), and Tom (9), (both played by Michael Shannon), a series of scary stories.

The stories center on a family led by shady businessman David and his trophy wife, Sara, who have two kids named, you guessed it, Mark and Tom.

One day, the couple receives a mysterious grandfather clock in the mail. While their initial inclination is to turn it away, the thing looks so old and interesting that they figure it might be worth some money, so they keep it.

Tick tock. Bad move.

Every night at 4:20 AM, the doors to the clock open and some creepy cardboard puppet-kids come out and do a little creepy dance. This is followed by the sound of scratching, which eventually moves beyond the clock and into the walls of the house, resulting in a lot of spooked out family members trying to figure out what the hell is going on.

Occasionally, we’ll break out of this story to come back to the Storyteller, who will tell little side stories about the characters, some of which turn them into different people doing inexplicable things.

One of my favorites was when Sara walks through the park to see a man standing next to tree with a bunch of whining dogs tied up to it. It turns out the man is digging a hole to bury the dogs in. He asks for Sara’s help, and she obliges.

But as the hole gets deeper, the man disappears, and the park’s residents, furious that this woman has stolen all their dogs and was planning to bury them, proceed to bury Sara alive! Yeah, talk about creepy!

Eventually, our family gets rid of the grandfather clock, but by then, it’s too late. The clock’s scratch-happy inhabitant has moved into the walls. And he’s not leaving until he turns a few family members into clock pie.

Just from this synopsis, you can tell there’s some fertile horror ground to play with.

But the script’s over-dependence on dream sequences made it hard to stay interested in. Dream sequences don’t fit well into movies. You should avoid them like gas station hot dogs. The few that succeed, though, tend to be of the horror variety. That’s because you can throw some creepy shit in a dream sequence and people will be scared.

However, if that’s all you’re doing, after awhile, the audience will pull ahead of you. They figure out your trick and get a general sense of what you’re going to do before you do. Once the audience is ahead of the writer, the movie’s dead. You can’t allow the audience to lead the parade.

For instance, we get a late scene where David is on a subway train and you just know he’s going to see something creepy (in this case, a woman with a weird screaming baby-face). Cause that’s how all these dream sequences have been.

1) Character enters location.

2) Something feels off about location.

3) They see something creepy.

The reason my favorite scene in the script was the Sarah-buried-alive scene was because it went against this formula. It was a different scenario that we weren’t used to.

This is something writers should be concerned about across all genres. Are they repeating themselves? Because if you’re repeating yourself in any aspect of the story, you’re giving the reader the opportunity to get ahead of you.

As I’ve said before, your job as a writer is to constantly monitor what you think the reader is expecting so you can give them something different. Use their expectations against them!

There’s a reason The Shining is more popular than movies like Suspiria and Jacob’s Ladder. All three films are good in their own way. But The Shining puts the most thought into its story. I strongly believe that audiences want to be led somewhere. They want you to take them. And if the rules get too blurry along the way, you lose them. Or at least, you lose a lot of them.

You also want to keep in mind that while this would probably make a really cool looking movie (there’s some creepy-ass imagery, that’s for sure), horror directors are experts in coming up with creepy-ass imagery. They don’t need you to achieve this part of the puzzle. What they don’t have, however, is the ability to come up with a captivating story. That’s where they’re weakest and so that’s your main way to tempt them. Give them a story they can’t say no to.

With that said, there’s something interesting about the writing here. There are some strong moments (the aforementioned buried-alive scene). I loved how Ashley SHOWED instead of TOLD in a lot of places. It’s just that, on the whole, it felt a little half-baked. You finish and get the sense that the fireplace storyline wasn’t thought through at all. You could’ve created some real tension in those scenes and punctuated it with a nice end-of-the-movie twist. Instead, the kids just go back into their tents and call it a night.

But hey, nobody said this screenwriting stuff was easy. Ashley’s got the tools. I’d like to see her use those tools to build a better foundation though.

Script link: Small Slices

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Beware the dream sequence in any of its forms. And if you are going to use it, use it sparingly. Most readers/audiences will get impatient if too much of the story is told in a formless state. Solid foundation-based storytelling is the way to go. Trust me!

One of the HARDEST things to do in Hollywood is be consistently good. There are so many factors working against making a good movie that very few people in the business are able to do it consistently. It’s why the writer-director of The Sixth Sense can also make The Happening. It’s why the director of American Beauty can also make Jarhead. It’s why the writer-director of the great Jerry Maguire can also give us… Aloha??

Think about all the things that can go wrong. The budget can be slashed in half at the last second. An actor can show up on set and demand a page 1 rewrite of his part. The director can drop out the day before the movie starts. The financing can come in suddenly, forcing you to start your movie before the script is ready. Your romantic leads who had great chemistry in rehearsals, can sleep together and, all of a sudden, the spark is gone. When you think about all of the things that are out of your control in filmmaking, it’s amazing that any good movies get made at all.

Which is why the people who do it consistently deserve attention. There’s a reason why these filmmakers are so obsessively coveted by the studios. Because they’re the only ones you can actually count on. So today, I’m going to give you five of the most consistently successful people in the business, and detail what they’re doing right that you can learn from. Let’s begin with the king of them all… Mr. Spielberg!

STEVEN SPIELBERG

Movies: Raiders of the Lost Ark, Jurassic Park, E.T., the upcoming Ready Player One

Spielberg is the best in the business at recognizing the big idea. But here’s the reason he’s so consistently successful with those big ideas while his imposters consistently fail. Spielberg adds a childlike sense of wonder to his stories, a simplicity of observation that makes them immensely accessible to both kids and adults. You see this even when he doesn’t have a child in the lead role. Spielberg still asks the question, “What kind of cool stuff would a child want to see here?” This formula for success shouldn’t be a surprise. It’s the same formula Pixar uses. Childlike wonder done with a level of sophistication. It’s such a simple approach, you wonder why others can’t replicate it. The reason is that everyone who tries to add that childlike sense of wonder goes too far into juvenile territory (fart jokes, “stepping in doo-doo” jokes – a big reason why The Phantom Menace failed). That turns off the majority of adult audiences, slashing the potential box office in half. The recent “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” is a good example of this approach in action. The childlike sense of wonder is replaced with a juvenile sense of pandering. It’s impossible for an adult to enjoy that movie, leaving the film successful, but a far cry from “Spielberg successful.”

JAMES CAMERON

Movies: Titanic, Aliens, The Terminator, The Abyss, Avatar

Whereas Spielberg appeals to the child in all of us, Cameron appeals to the teenager in all of us. He ramps up the Spielberg “big idea” approach and adds a new ingredient: “attitude.” As much as I love Spielberg, he’ll never direct an action sequence as cool as the LA aquaduct chase in Terminator 2. Speaking of that scene, Cameron is one of the few directors who thrives on pushing the envelope. If you watch most Hollywood movies, it’s directors copying whatever the latest big movie did (remember how many movies did “bullet time” after The Matrix?). Cameron asks himself, “What can I do that’s never been done before?” Just by asking that question, you open your story up to amazing possibilities. A lesser known key to Cameron’s success is his “on-the-nose” approach. Cameron is not afraid to spell it out for audiences (Sarah Conner’s drawn out voice-overs detailing our inevitable demise as a species in Terminator 2, for instance). But while this may annoy frequent cinephiles bored with conventional film, the casual moviegoers who need a little more clarity in their cinematic cereal love it. Here’s the interesting thing though. Film snobs hate every other on-the-nose filmmaker outside of Cameron. How does he manage to escape their wrath? Because there’s no other filmmaker more obsessed with detail than Cameron. The guy fucking spent years inventing alien plant life for his fake world in Avatar. Geeks LOVE that shit. Because details matter. Consider the hack who recently took over the latest Terminator movie. In that film, a key scene from the first movie is recreated. Except the director decided to CHANGE one of the character’s hairstyles (he had a blue Mohawk in the original – not in the new one)!!! It’s this casual attitude towards details that leads to so many forgettable films.

DAVID FINCHER

Movies: The Game, The Social Network, Fight Club, Benjamin Button, Gone Girl

Just like Cameron, Fincher is OBSESSED with details. Except whereas Cameron is obsessed with his worlds and his props and his gadgets, Fincher is obsessed with everything in the frame, from the lighting to the set decoration to the camera angle to the positioning of the actors to the placement of that whiskey bottle on the back mantle that nobody in the audience is ever going to notice. When you watch a David Fincher movie, you’re watching a film from a man who CARES. And that’s not always the case with movies. In addition to this, Fincher has an amazing ability to identify dark populist material. He is, in many ways, the R-Rated Spielberg. One thing that’s separated Fincher as of late is his interest in structurally challenging stories. From Fight Club to Zodiac to Benjamin Button to Gone Girl, these are movies that don’t have that safe straight-forward Act 1, Act 2, Act 3 setup. While I believe you need to learn to tell simple stories first (which is exactly what Fincher did, with movies like Panic Room and The Game), once you have that understanding of traditional structure down, scaring yourself and taking on non-traditional narratives is a great way to stand out.

QUENTIN TARANTINO

Movies: Pulp Fiction, Inglorious Basterds, Django Unchained

Tarantino is probably the hardest screenwriter/director to learn from because his style and voice are so unique, if you try to do what he does, you end up looking like a not-as-good version of Quentin Tarantino. With that said, there are a couple of things we can take away from the man. More than any other writer in the business, Tarantino creates strong fascinating memorable characters. Almost every one of his characters is unique in some way, is larger-than-life in some way, and is fun to watch on the screen. In so many scripts I read, writers put little effort into creating characters that stand out. I get the feeling whenever Tarantino sits down to write a character, he asks himself, “How can I make this character memorable?” And he goes from there. A lot of people assume the key to Tarantino’s success is his dialogue. But that’s not true. The reason his dialogue is so good is because he makes his characters so interesting in the first place. If you write interesting characters, they’re going to say interesting things. Which means the dialogue writes itself. This is also why Tarantino can stay in scenes for so long. It’s because of the work he did long before those scenes were written (creating unique interesting characters). So if you want to be like Tarantino, don’t try and write “cool,” or “weird” stuff. Ask yourself for each one of your main characters: “How can I make this character interesting and memorable?” Do this and everything else will fall into place.

CHRISTOPHER NOLAN

Movies: Memento, Inception, The Dark Knight, Interstellar

Nolan doesn’t yet have the pedigree that the rest of the entrants on this list have, but he’s done all right for himself. And there’s one thing Nolan does better than anyone I’ve mentioned so far. He’s not afraid to make you think. Nolan sees the theater as an opportunity to not just entertain an audience, but to challenge them. And unlike a lot of other filmmakers – like David Lynch, like Darren Aronofsky – who likewise enjoy challenging audiences, Nolan is the only one who likes to do so in big high-concept packages. The formula almost seems too obvious. Big ideas that make you think. Why didn’t I think of that? Another thing that Nolan does well is he takes a realistic approach to all of his big ideas. He’s like the anti-Michael Bay in that sense. Whereas other blockbusters (Independence Day, 2012) feel hokey in their approach to physics and logic, leaving the story feeling schlocky and cartoonish, this “realism above all else” approach gives Nolan’s films an additional layer of depth. As crazy as some of the ideas are (dream heists?) you get the feeling that if they were introduced into the real world? This is how they would go down.

My big takeaway from these five titans? Come up with a big concept. Treat it with a childlike sense of wonder or realistic plausibility, whichever you think will work better for your particular idea. Challenge yourself to create larger-than-life memorable characters. Push yourself into narrative areas that make you a little afraid. And above all, pay attention to the details. Now go write that million dollar spec!

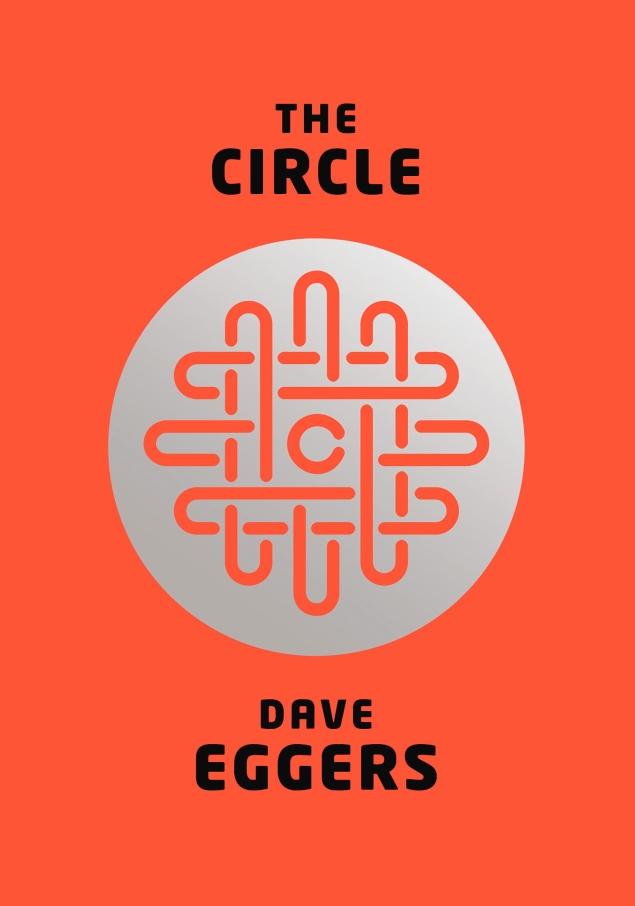

Genre: Social Media Thriller??

Premise: A young woman eagerly joins the fastest rising tech company in the world, losing herself in the company’s agenda to rewrite how we live our lives.

About: This project is rapidly approaching red-hot status. It stars Tom Hanks, Emma Watson, John Boyega (Star Wars: The Force Awakens) and internet demigod, Patton Oswald. The script was written (and will be directed) by James Ponsoldt, bassed on the novel by Dave Eggers. Ponsoldt is best known for his realistic exploration of high school in The Spectacular Now. But with “Circle,” he’ll be entering a whole new stratosphere in terms of budget and pressure. This has some high-octane (and blazing hot) actors in the film, with Boyega and Watson being on everyone’s “must have” list. This script must be amazing, right! Dave Eggers is a well-known novelist who tends to divide critics with his books. His most famous works include A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, You Shall Know Our Velocity, and A Hologram for the King (which Tom Hanks will also star in).

Writer: James Ponsoldt (based on the novel by Dave Eggers)

Details: 141 pages – November 22, 2014 draft

If you’re like me, you’re asking, “141 pages?? Why so long, bro??” Well, the first 20 pages of The Circle are dedicated to touring The Circle campus. If you can’t cut a tour down to under 20 pages, chances are your script’s going to run long.

And that’s what worried me when I remembered Ponsoldt wrote/directed “The Spectacular Now.” Now I liked The Spectacular Now. I thought its realism and unique angle into the traditional high school movie helped it stand out.

But if there was a problem with the script, it was that it didn’t have a plot. It kind of drifted along without a narrative spine. That can be done in a character piece, but if you have a thriller – like The Circle – you’re going to need structure. There needs to be goals, stakes, and urgency. And those first 20 pages of The Circle didn’t display any of that. How bout the last 120 pages?

24 year-old Mae Holland is having a rough time of it. Her father recently got diagnosed with MS and she’s got a shitty job that doesn’t pay the hospital bills.

That changes when she gets a job at The Circle. The best way to imagine The Circle is a cross between Google AND Facebook. Which is a little confusing, since the two companies couldn’t be more different. But that’s something you’ll want to get used to with this script. It’s pretty damn confusing.

Anyway, so Mae starts working for a department called “Customer Experience,” and quickly realizes how obsessive The Circle is. Every few minutes, her bosses check in on her via text. “You okay?” “Anything we can do?” “Why did you only get a 97 approval on your last customer experience?”

The thing is, Mae’s a trooper. She never gets too upset and so takes the texts in stride. This will prove to be her undoing, when the company announces that they’re ushering in a new technology called “Transparent,” that forces its employees to wear a camera wherever they go so that their lives are broadcast to the world 24/7. And Mae will be one of the first users!

As a result, Mae becomes a celebrity, with millions of followers watching her every move. Mae is out front on every mandate The Circle lays down, including its desire to legally FORCE every single person in the United States to sign up for a Circle Account.

As Mae’s 24/7 broadcast begins to freak her friends out and shrink her social circle, Mae continues to push the message, making sure the world knows that The Circle is the future… to everything.

Let me start off by saying…

What the fuhhhhhhhhh????

This has to be one of the strangest scripts I’ve read all year. If the idea here is to go with a zany-Janey-tone, a la The Truman Show? Maybe this movie has a shot. But I don’t know, man. This fucking thing is all over the place.

In fact, if I were pitching it, I would call it a social media thriller that focuses on a Google-Facebook company in the vein of 1984, that infuses itself with a touch of Scientology, and a healthy homage to the Matthew McConaughey starrer, ED TV. Hell, it even adds a little bit of Real Genius, with the company founder sneaking around campus in disguise half the time.

It’s just sooooo fuckkkkkking weird, dude.

But seriously, I never once understood what this script was trying to say. It starts off as a typical thriller, where we walk into a company and everything seems too perfect.

We gradually learn the company is evil, starting with its plan to put lollipop-sized cameras everywhere so they can watch everything.

This shifts to The Circle wanting to control the Senate.

That shifts to them wanting to do a Scientology-esque “transparence” thing, where Mae wears a camera wherever she goes. Then Mae turns into Matthew McConaghey’s character in ED TV, becoming a reality superstar.

Finally The Circle wants to pass a law to force everyone to sign up for an account and extend that into a FORCED PRESIDENTIAL VOTE! And if that doesn’t tickle your tailfeather, one of the final scenes has Mae chasing her ex-boyfriend in a pick-up truck with a dozen drones, broadcasting the stalking maneuver live in front of an audience, with them laughing away like a pack of crazed hyenas.

Okay, so let’s say that Ponsoldt miraculously nails the tone here. I hope he does. Because maybe we get a David Lynch version of a thriller.

But even if that happens, there’s still a major problem. Mae Holland is the most boring protagonist I’ve read in 2015. Not only is she dumb, but she spends the majority of the movie nodding her head, doing what others tell her to do, and not making any critical decisions on her own.

She is the world’s most reactive protagonist.

And I am SHOCKED that Emma Watson, the face of feminism, is okay with this. She’s playing a character who does what every man in this movie tells her to do.

For those of you wanting to avoid writing boring characters, what do I mean by this? What makes a protagonist boring? Well, remember this. The most important thing you can do for a character is give them a goal. If they have a goal, they will be ACTIVE in pursuing that goal, which immediately makes them interesting as a character, since we’ll instinctively want to see if they succeed in achieving their goal. We get none of that with Mae. Mae shows up at work and does whatever anyone says she should do.

In addition to this, you want something going on inside of your character. This is what gives them that elusive quality of “depth” all these producer-types keep telling you you don’t have enough of. Whether it’s a flaw they’re trying to overcome or something from their past they can’t quite resolve, they need to be battling something.

Mae isn’t battling anything. Her father is battling MS. But that’s her father. Occasionally, she’ll get upset about it. But never does this challenge her in a compelling way. If Mae was a workaholic and it caused her to abandon her father and family in their biggest time of need, now you have something. But we don’t get anything like that here.

I recently watched a documentary called Maidentrip, about a 14 year-old girl, Laura, who sails around the world all by herself. Eventually, it’s revealed that Laura was devastated when her parents divorced, her mom moved away, married someone else, had a NEW daughter, and then barely spoke to Laura anymore. This sailing adventure was a way to run away from that problem. But Laura eventually realizes she can’t run away from this. She must face it.

That’s what I mean by INNER conflict – something/anything your character is battling inside that can add more than what we see on the surface. This tiny little documentary had that. This big studio flick, unfortunately, did not.

In closing, all I can say is I hope they tightened up the script. My instinct is to say that the source material is faulty. Eggers’s stuff has always been a little left-of-center and maybe not the best material to turn into a movie. But Ponsaldt doesn’t help by drawing the narrative out and, as a result, exaggerating the story’s lack of focus.

And focus is everything in screenwriting. A script needs to be tight. This was very much the opposite.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re trying to say a million things with your screenplay, you won’t say anything. That was the problem here. A lollipop-camera takeover of the world, broadcasting our lives 24/7, exploring the cult mentality of tech businesses. It was too much to wrangle in, which led to The Circle feeling scattered and confused. Pick one!