Genre: Horror/Slasher

Premise: Years after a girl’s actress mother dies in an accident, the girl and her friends are transported into an 80s slasher movie in which her mother was one of the stars.

About: This script has always had some buzz going for it, and now that the film’s in the can, that buzz is only growing. You like how I’m using hip Hollywood lingo today? “In the can.” I keep that up and you guys will probably put me in my own slasher movie. Where all of you are the killers. The Final Girls is co-written by Joshua John Miller, whose inspiration probably came from the fact that he starred in an 80s horror film himself (the 1987 film, Near Dark, directed by Kathryn Bigelow). Miller’s younger co-writer is M.A. Fortin, who appears to be in charge of helping Miller understand what kids do and say today. Fortin gained recent recognition by writing the Rose McGowan directed short film, “Dawn,” which you can watch here.

Writers: Joshua John Miller & M.A. Fortin

Details: 107 pages (Revised draft – February 25th, 2011)

I really loved last week. Not just because I got some time off, but because you guys really picked up the slack. It was one of the best commenting weeks in the site’s history. I especially loved all the movie suggestions on Friday. I was able to squeeze a few of your suggestions in and I’ve been pleasantly surprised.

Compliance, in particular, got me revved up. What the hell! I can’t believe this actually happened! Watching the real life interview afterwards and the manager saying she never saw that the girl was naked with her boyfriend as the interviewer WAS POINTING OUT THE FOOTAGE showing her walking past the girl when she was naked with her boyfriend… I was furious. I don’t know if everyone will like this movie but I guarantee you this. You won’t walk away from it without having a response.

Can the same be said for The Final Girls? Different type of movie entirely. But maybe a more rewarding experience in the end.

14 year-old Maxine “Max” Cartwright waits in the car as her aging actress mother, Amanda, emerges from another failed audition. Amanda, it turns out, is one of those actresses who’s only been able to nab “the hot girl who gets killed in B-horror movies” role. And now, with her beauty fading, there aren’t many of those roles left.

In fact, there aren’t going to be any. Because on the drive home from the audition, their car skids off the road, crashes, and Amanda dies.

Cut to 3 years later and Max is now a senior in high school sporting the kind of style girls who lost their moms sport (aka: combat boots, nose rings, black clothing). Her lifelines are her geeky best friend Gertie, her once-sorta-crush, Chris, her “m’lady” horror obsessed pal, Duncan, and her once best friend now turned frenemy, Vicki.

While Max tends to avoid all social encounters if possible, Duncan convinces her to come to his screening of Camp Bloodbath, an 80s horror flick that her mom starred in.

The whole crew arrives, the movie starts, and Max is actually having a good time. That is until someone accidentally starts a fire that sweeps through the theater. In a mad dash to escape, Max and her friends cut through the movie screen, only to pass out and wake up… in the woods.

When an old hippie van passes and Max’s mom sticks her head out asking where Camp Bluebird is, the group realizes the impossible. They’re inside the movie they were watching! And shockingly, for Max, she’s face to face with her mother again! Or, at least, the character her mother is playing, Tina.

After the group accepts this craziness, they realize that the only way out of the movie is to wait for Hatchet Face (our killer) to be killed by the movie’s lone virgin, Paula. But when the group accidentally kills Paula, that leaves Max and Tina as the lone virgins, and therefore the only two who can kill Hatchet Face and get them back to reality!

These types of scripts almost always catch peoples’ attention. The idea of being caught in a movie allows you to play with conventions, with genre, with stereotypes. The possibilities are endless. It’s the reason why Last Action Hero was one of the most famous script sales ever.

But where Last Action Hero failed to exploit its concept, The Final Girls uses its razor-sharp machete to exploit every angle possible. But its biggest achievement? It made the journey PERSONAL.

What do I mean by that? Whenever you come up with a cool concept – heck, whenever you come up with ANY idea – you have a choice. You can execute only the idea. Or you can find a way to add a PERSONAL SLANT to it so that you’re exploring your characters as well as the plot.

Miller and Fortin made the genius choice to not only send our characters inside a horror movie. But send them into a movie where our heroine’s dead mother is playing one of the parts. All of a sudden, a fun little slasher movie becomes a lot more.

They did the same thing with Back to the Future. Bob Gale and Robert Zemeckis could’ve easily sent Marty McFly into a generic past and focused solely on the plot to get him back home. But they made that movie a character-exploration haven by adding the parents. Marty had to get his parents to fall in love or cease to exist forever. That’s what I mean by adding a “personal” component. Something PERSONAL should be on the line for your protagonist.

Truth be told, I would’ve been through with The Final Girls by page 45 if it weren’t for the personal component. Instead, I was asking, “How is Max going to tell Tina that she’s her mom? How is Tina going to react? Can Max get closure from a woman who’s not technically her mom? Is Max going to be able to take her mom with her?” I was really invested in that relationship, which was the key to the script keeping my attention for 110 pages.

Outside of that clever inclusion, the script was good but not great. I liked that as soon as the characters realized they were in a movie, they formulated a plan (the GOAL). Lesser writers would’ve had our heroes randomly picked off one by one until the movie was over – no shape or form needed. But as you Scriptshadow Readers know, you never want to leave your main characters in a reactionary or passive state. They should always be STRIVING FOR SOMETHING.

That keeps them active, which keeps the story energized. So the group lays out a plan (kill Hatchet Face to get back to the real world) and now we can watch to see if they succeed.

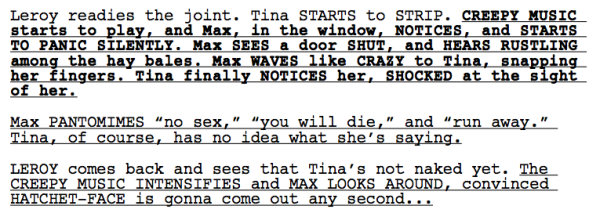

The only knock against the script was the terrible writing style. It was too thick for a slasher script and had way too much affected writing. Here’s a small sample of what the script read like.

But beyond that, this was so much better than your average generic slasher script. It showed a willingness to try something different, to have fun, to be creative. And these are things readers don’t see enough of. Which made The Final Girls a welcome surprise.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If all you do is execute your concept, even if it’s a great concept, readers will usually tune out on page 45 (that’s 15-20 pages into the second act). The concept is what gets the reader in the door keeps them invested through the first act. Once you achieve that, you have to find the PERSONAL ANGLE that’s going to make the reader give a shit about your main characters and what they do. The Final Girls is a great example of a script that found the perfect personal angle (what if you were sent to a place where you got a chance to reconnect with your dead mother, albeit in an altered state?). That’s what elevated the script above your typical slasher fare.

This might be my last post until Tuesday (day after Labor Day). I thought we’d finish up Vacation Week with a good old fashioned “Unknown Movies Referral Thread.” It’s a 3-day weekend. Help your fellow Scriptshadow brethren experience a new film by suggesting a little known favorite of yours. If you can suggest a great movie that I’ve never heard of, I will personally send you Scriptshadow Brownies. So… waddaya got!!?? (my recommendation is up above)

So yesterday was interesting. I gave you four trailers and asked which ones you’d go to the theater and pay for. The clear winner was The Martian, the biggest piece of Intellectual Property on the list. The reason I find this interesting is because screenwriters are always complaining about the lack of original ideas available at the cinema and how studios keep adapting material from other mediums. Which is what The Martian is.

Therefore, today’s question is this. And I want you to think hard about it because, if you’re paying attention, your answer should inform you what kind of script to work on. What is a spec movie idea that you’d actually go out and pay to see? Or, if that’s too general, what kind of movies are they not making at the moment, that you would DEFINITELY pay 12-15 bucks for? If you can answer that question, and a lot of people agree with you (with upvotes), you should bust open Final Draft and start writing.

I don’t have much to say at the moment. I’m too busy sucking in the fresh vacation air. But to get you guys talking, here are four trailers that are hotter than a freshly baked pop tart. What are your thoughts? Which ones will you definitely go see in the theater? Which will you wait to hit digital? Which will you not watch even if someone threatens to shave off your skin with a potato peeler? We always talk about concept and what drives people to go pay 12 bucks at the box office. Well, make your predictions and let us know what you think will DEFINITELY be a hit… or a miss!

I hope all of you are getting some writing done, dammit. But in case you need to procrastinate, the topic du jour is Max Landis’s movie, “American Ultra.” The film didn’t do well on its opening weekend, finishing with 5.5 million bucks and a 48% Rotten Tomatoes score. I think they were hoping for Zombieland-like numbers (24 million bucks – 90% RT score).

Now I sympathize with ANYONE who has to go through an opening weekend. They are, quite honestly, one of the most fucked up masochistic business endeavors anyone could subject themselves to. You spend 3-10 years writing a script, looking for financing, finding stars, trying to get a green light, making the movie, cutting it together in post… all to see how it does between 3pm and 10pm on a Friday evening. Because it’s at that moment when you know whether you have a hit or a bomb. It’s an insane way to live your life – to engage in a business plan like that.

And because of that, when something does go bad, everyone involved in the project buries their head. But Max Landis, the tweeter of all tweeters, jumped right in and owned up to the failure. Or did he? I’m not sure if he’s blaming this movie on himself or the general population. Here’s what Landis tweeted:

So here’s an interesting question: American Ultra finished dead last at the box office, behind even Mission Impossible and Man From Uncle…American Ultra was also beaten by the critically reviled Hitman Agent 47 and Sinister, despite being a better reviewed film than either…which leads me to a bit of a conundrum: Why?

American Ultra had good ads, big stars, a fun idea, and honestly, it’s a good movie. Certainly better, in the internet’s opinion, than other things released the same day. If you saw it, you probably didn’t hate it. So I’m left with an odd thing here, which is that American Ultra lost to a sequel, a sequel reboot, a biopic, a sequel and a reboot. It seems the reviews didn’t even matter, the MOVIE didn’t matter.

The argument that can/will be made is: big level original ideas don’t $. For the longest time, my belief was that the 80s/90s were the golden age of movies; you never knew what you were going to get. Am I wrong? Is trying to make original movies in a big way just not a valid career path anymore for anyone but Tarantino and Nolan?

That’s the question: Am I wrong? Are original ideas over? I wanted to pose this to the public, because I feel, put lightly, confused. I feel like I learned a lesson, here, but have no idea what it is. I once joked “there’s only so many times people will go see Thor 2.” Sorry to be kind of a downer guys. It’s just a little frustrating to see John Cena squash Kevin Steen. Metaphorically.

Landis makes some good points. But there are a few he’s maybe twisted in his favor. Did American Ultra have “big stars?” Is it a “good movie?” Was this even a good idea? I think you limit yourself with the “Dude, I’m so high” crowd, but Pineapple Express road that subject matter to riches. It’s sad because this was one of the movies in my “Please Save The Day Specs” post. What do you guys think? Is what Landis is saying legitimate? It certainly hits on a lot of things we’ve discussed here before.