Search Results for: the wall

Don’t worry. I give you five genres that you, as a spec screenwriter, can still write that get released in movie theaters!

A question I get asked a lot is, “How does a good script become a bad movie?” The prevailing thought is that if it’s on the page, all you have to do is point the camera and get out of the way. Unfortunately, reality doesn’t work like that. From actor rewrites to budgetary rewrites to a director shifting the script’s tone to miscasting… a lot can happen between great script and cameras rolling.

I bring this up because I loved the Ambulance script by Chris Fedak. It was such a fun ride with all these cool twists. Most action films are pretty bland, plot-wise. This one was constructed in such a clever way. So I was rooting for the movie. However, it did not do well this weekend, not even breaking 10 million at the box office.

That is not to say Ambulance is a bad movie. I don’t know if it is or isn’t. It seems to be getting good reviews for a Michael Bay film. But its failure at the box office is concerning considering that “theatrical” has become such an unknown in 2022. It feels like every movie’s success or failure is redefining the box office on the fly.

The first thing we have to take into account is streaming’s rise and theatrical’s fall during the pandemic, and how that reset audience’s expectations in regards to what they would and wouldn’t pay for. I lump both those in together because if they hadn’t happened at the same time, I believe theatrical would’ve weathered the storm. But because the streaming wars forced streamers to come up with bigger and better product to jack up those subscription numbers, along with people getting used to not going to the movies, it created a perfect storm scenario for a box office apocalypse.

I think people looked at “Ambulance” and they said, “Hey wait a minute. Didn’t I just see that action movie on Netflix for free that had a bigger budget and a bigger star in “Extraction?” Once you give people something bigger for “free,” they no longer value paying for it. I mean, hell, we even got a bigger budget Michael Bay movie on Netflix not too long ago, “6 Underground.” So why would you go to the movies and pay for a Michael Bay movie?

Another problem is the budget. The movie only cost 40 million dollars. Considering that the average Bay movie cost north of 200 million, the movie couldn’t help but look “Bay-light.” Why am I going to the movies to check out a small film by a filmmaker who makes big movies? Or, if that question seems too industry-coded, look at it from the average moviegoer’s POV. They see a trailer for a movie called “Ambulance” and all it contains is a bunch of shots of an ambulance car chase and it’s kind of like, “So what would normally be one scene in a Michael bay movie is now…… the entire movie?”

A third factor I haven’t heard a lot of people talking about is the fact that Bay’s style is starting to feel dated. The sweeping dolly shot at sunset where the actress or car is bathed in golden sunlight… it feels very 1999. You’ve got these newer action filmmakers, guys like Sam Hargrave, the Russo Brothers, Chad Stahelski, and David Leitch, who have a darker grittier more inventive style with much fresher action choreography. These guys are more interested in making you feel the visceral physicality of two men beating each other to pieces than they are making sure that every strand of those actors’ hair is in place.

This is a long way of saying, you see the Ambulance trailer and think, “What’s new here?” That’s what sucks about good scripts that don’t have their goodness baked into the concept. The goodness is in the way the story is executed. And you don’t know that unless you see the film.

What Ambulance’s failure says is that the mid-to-high range action movie may no longer be worthy of a theatrical release. Seeing as this is a screenwriting site, I’d like to discuss what this means for screenwriters and how you can adapt. Because what everyone fears is that theatrical has become, exclusively, a superhero industry. And that it’s only a matter of time before all the other genres slip down the slope into that large gargling mouth belonging to the streamers.

Let me alleviate those fears by first giving you some non superhero genres that still get theatrical releases and then giving you scripts written on spec that can still become theatrical releases. Because, as of this moment, there are still options. Let’s look at them.

NON-SUPERHERO MOVIES THAT STILL GET THEATRICAL RELEASES

Giant IP Action Movies – Fast and Furious, James Bond, Mission Impossible – With these movies, you have to give the audience a combination of 3 things – a big movie star, wall-to-wall giant set-pieces, and at least one major thing in the movie that people haven’t seen before that you can build a marketing campaign around. Mission Impossible is famous for this. They put Tom Cruise on the side of a plane while it’s taking off. To get into this space is tough because the first time you try to do it, you don’t have as much money as the established IP does. So you’re already at a disadvantage. We saw this with Uncharted. It was a boy amongst men and even though Sony put a lot of money behind the marketing, it only barely snuck into the “BIG IP ACTION MOVIE” conversation, with a 51 million dollar opening. Giant IP Action is probably the most competitive space in theatrical movies at the moment.

IP Horror – The reason horror is always going to be in the conversation is because 12-18 year olds love to be scared. And that demo, despite what some may say, is still showing up to theaters if the brand is big and exciting enough. IP horror has been a rather recent development as the Blumhouse formula made it seem like you only made a ton of horror movies for 5 million bucks each and hoped one of them broke out. But ever since The Conjuring and It, they’re sinking a lot more money into these films so that they feel more like events.

Animation Movies – Pixar, Disney, Dreamworks. These are always going to do well because they spend a ton of money and time on them. Because animation is something that can be manipulated up until the last second, they can test the sh#t out of these movies internally, figure out what’s wrong, then go back and fix them. With a regular movie, you’re sort of locked in once you finish production. Yes you can reshoot, but reshoots cost tons of money and don’t allow nearly as much flexibility as animated productions. Long story short, they don’t release these things until they know they’ll print money. That and parents want to get out of the house with their kids every once in a while and movies are one of the cheapest forms of entertainment out there.

Action-Comedy – Action Comedies are right on the brink of becoming streaming movies. I think Red Notice made the industry believe that was the direction we were headed. But as of now, if a studio loves an action-comedy idea, they’ll still release it theatrically. The more I dig into this, the more I think it might become one of the rare genres that live in both universes. Netflix may just act as a de facto studio in this case, releasing action-comedies to compete with theatrical action-comedies. Free Guy, Jungle Cruise, The Lost City, The Hitman’s Bodyguard, Spy.

Biopics/True Stories/Book Adaptations – Hollywood loves to celebrate itself, and these are the three genres it does it with. Movies like House of Gucci, Spotlight, Little Women, Wolf of Wall Street. There’s a chance these could slide into the streaming universe soon but I’m not convinced it will happen. I don’t think the Academy wants all the movies it nominates to be on streaming. It should be noted that true stories can be written as spec scripts, so you could place them in that category as well. The only reason I’m hesitant to do that is because studios tend to like when you base your true story on a published work and most non-working screenwriters can’t afford to option those works. But it’s possible to find a great true period story that hasn’t been told before and just write it without any source material. If you can place on the Black List, like Spotlight did, some big people will take notice and, possibly, you get your script produced.

NON-SUPERHERO MOVIES THAT STILL GET THEATRICAL RELEASES THAT ANY SPEC SCREENWRITER CAN WRITE

Clever/Fresh Horror (A Quiet Place, Get Out) – The best bang for your buck option. Basically what you want to do here is focus on smartly written character pieces that center around family and then, for the majority of the screenplay, keep your monsters unseen. Let the horror come out of our imagination. That’s what both A Quiet Place and Get Out did, which is why they became phenomenons. Another thing about keeping these movies character-driven is that they’re cheap to make, which means more buyers. And if the idea is cool enough and you’re lucky enough to get a director who hits it out of the park, you get that big studio release. This is the genre where the most writers and directors come out of.

Guy with a Gun movies (John Wick, Nobody, Sicario, The Accountant) – This one may be confusing as I just said that mid-to-high range action movies are moving to streaming. But here’s the thing. “John Wick” is a formula studios are going to keep trying to replicate because a) the guy with a gun formula has been around forever so studios know that it works, and b) everyone outside of Disney is desperate to find new franchises and this is one of the best ways to do so because you don’t have to spend a ton of money on the first film so it’s a relatively cheap risk. Going back to Ambulance, if there’s one problem with that project, it’s that it’s not a clear “guy-with-a-gun” scenario. It’s not something you can build a franchise on. Another twist to note here is that studios have been trying to create the girl-with-a-gun genre for a while now and it just hasn’t worked. Kate, Gunpowder Milkshake, The Protege, Ava, Atomic Blonde, Proud Mary, Peppermint. I don’t know why these aren’t catching on. It could simply be that they’re bad movies. It could be that they haven’t found an “Angelina Jolie circa 2003” or “Scarlett Johansen circa 2012” actress that elevates these films. But the industry has cooled on girl-with-a-gun movies as a result. That’s not to say you shouldn’t write them. But I think the pendulum in this genre has swung back to the male side. And if you’re looking for someone to write for, Nicholas Cage is about to have a comeback moment where studios start putting him in big movies again. So start there.

Action Comedy (Free Guy, Jungle Cruise, The Lost City, The Hitman’s Bodyguard, Spy) – Yes! We have a crossover here! Action-Comedy is one of the best genres that spec screenwriters can write because it’s one of the few genres that if you nail it, you get the full Hollywood treatment. You get the big stars, the big budget, the big marketing push. You could end up as one of the top 15 movies of the year with a smart concept. I just wrote in my last newsletter how the 80s and early 90s are filled with high concept movies that you can draw inspiration from. People under 35 don’t know that much about this era. So you have advantage if you’re older and know this time well. Cause these types of flicks were huge back then.

World War 2 Movies (Dunkirk, Hacksaw Ridge, The Imitation Game, Flags of Our Fathers) – Sometimes I think the best advice I could give a new writer is to write a World War 2 script. There are just so many stories from that war and Hollywood never tires of them. They absolutely love that war. Not “love” it. But you know what I mean. And if I were you, I would look to create a contained time scenario in order to make it a really tasty spec. Someone just wrote one of these that I reviewed. I can’t remember what it was called (can any of you find it?). It was about a soldier who had to make it through a forest swarming with Nazis in a couple of hours to deliver a message or something. Something like that hits all the beats because you not only have the draw of World War 2 that Hollywood loves, but you have that tight clean exciting read by making it real-time.

Zombies/Vampires (World War Z, Zombieland, I Am Legend, upcoming Nosferatu, Let The Right One In) – I might get some pushback for this one because there hasn’t been a big zombie or vampire movie in a while. But you know what that tells me? THE NEXT WAVE OF ZOMBIE AND VAMPIRE MOVIES ARE COMING. These two genres never die, no pun intended. As is the case with every new iteration of these sub-genres, don’t bother writing them unless you a) love these movies, and b) have a fresh take on them. Cause in order to reboot a genre, you need to be the person with a new take on it. A quick concept trick on how to create “fresh takes.” If a genre has been really serious for a while, create a light/comedic take. If a genre has been really light/comedic for a while, create a serious take. That’s what Zombieland did on the heels of those Dawn of the Dead type movies and it became a phenomenon.

Bonus: Any Really Clever Premise – If you have a truly great idea or a truly ironic idea (Jurassic Park, Yesterday, Good Will Hunting, Source Code, The Hangover, Back to the Future, The Sixth Sense, Rear Window, Memento), these can get into theaters. The reason is that, when a truly great idea hits Hollywood, everyone in town gets excited about it, and they all start competing to work on it. So you end up getting an amazing director and an amazing actor and, if you do that, there’s no way they’re not releasing the movie theatrically. Since everybody thinks their idea is amazing, here’s a quick test. Send your logline to three people. If all three of them don’t say, “Oh my god, that’s an amazing idea,” it’s not an amazing idea. Or you can just come to me for a logline evaluation and I’ll tell you ($25 – carsonreeves1@gmail.com). That doesn’t mean it’s not a good idea. It’s just not a great idea and, therefore, it’s probably not theatrical-release worthy.

Let me be clear that there are always going to be exceptions. If you can write a script that wins over a revolutionary director like Darren Aronofsky, the Safdie Brothers, or the Daniels, yeah, you can be one of the rare lottery winners. Hell, that’s arguably what happened today. Ambulance won over Michael Bay, which means a script that normally wouldn’t get a theatrical release did. The only problem with this strategy is that you’re basically betting on the fact that one of ten directors in the world has the exact same interest as you do with your rare weird screenplay concept. If you have information on a director and know they’re looking for a specific subject matter and it just happens to be subject matter you love as well, writing that script makes more sense. But if you’re just hoping, you’re playing the lottery.

Just to be clear about today’s post, this is what you should write if you want to get a THEATRICAL RELEASE. It’s not necessarily the best way to break in. The best way to break in is, unfortunately, less glamorous and takes more time. You write a really powerful script that you’re extremely passionate about, hope to get on the Black List so that people learn your name, those people check out your script, you gain some fans, you get meetings with those fans, and you pitch them on adapting one of their projects. It’s a longer route but it’s the more common route.

I hope this helps!

REMINDER – THE FIRST ACT CONTEST DEADLINE IS MAY 1!!!

I need your title, genre, logline, anything you want me to know about the script, and, of course, a PDF of your first act. You want to send these to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the subject line “FIRST ACT CONTEST.” The contest is 100% free.

What: The first act of your screenplay

Deadline: May 1st, 11:59 PM Pacific Time

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Include: title, genre, logline, extra info, a pdf of the act.

Cost: Free!

The Final Essential First Act Ingredient: GSU!

Day 1: Writing a Teaser

Day 2: Introducing Your Hero

Day 3: Setting up Your Hero’s Life

Day 8: Keeping Your Scenes Entertaining

Day 9: The Inciting Incident

Day 10: Refusal of the Call

Day 15: Dealing with Exposition

Okay, let’s summarize everything we’ve learned so far about the first act.

We’ve either written or not written an opening teaser scene depending on our genre. We’ve introduced our protagonist in a strong memorable way. We’ve set up that protagonist’s life, including their friends, their family, and their job. We’ve set up an antagonist. We’ve constructed our scenes so that they’re entertaining and not only there to convey information. We’ve introduced an inciting incident that has rocked our hero’s world, creating a problem. Our hero is then forced to make a choice: Do they or do they not go off on a journey and try and solve this problem? The hero will, in most cases, refuse this call to adventure. Just like us, heroes hate change. They would rather stay in their comfortable little bubble than do anything dangerous. However, in the end, whether a secondary plot beat forces them to or because they decide on their own, they accept the call to adventure and off they go, into the second act.

That’s it, right?

We’re in the second act now. We’re done. Finito el first acto.

Not quite.

Because there’s one last thing you need in place before you leave your first act.

GSU!

Long-time readers of the site know what GSU is but for those don’t, here’s a quick recap. “G” stands for “Goal.” It is the character goal that will drive the majority of the story. In The Batman, the goal is to find and stop a serial killer (The Riddler). In Jungle Cruise, the goal is to find the treasure in the jungle. In Old, the goal is for the beachgoers to get off the beach before they all die of old age. In Marry Me, the goal is… actually I have no idea what the goal is cause I still don’t understand that movie or why anybody made it.

In some scenarios, the goal will be driven by characters other than the hero, such as the villain. In Empire Strikes Back, the primary goal is Darth Vader’s. He’s trying to find Luke Skywalker. I bring this up because writers get confused as to what to do when their hero doesn’t have a goal. In those cases, somebody else in the story has to have the goal. If no key character has a strong goal going into the second act, boy are you making things hard for yourself.

“S” stands for “Stakes” and you’ll note that you can’t have stakes without a goal. The goal causes the stakes. For example, let’s say your character needs to find 50,000 dollars or else the bookies he owes money to will kill him, like Uncut Gems. The goal (getting the money) is what dictates the stakes (or else they kill him). You want the stakes to be as high as you can make them relative to your story.

What I mean by that is, if you’re writing a romantic comedy, it doesn’t make sense for the stakes to be life or death. Life or death stakes are for different types of movies. But if we establish that the girl our hero wants is someone he’s been in love with for 20 years, and this is the only chance he’s going to get to be around her, then those stakes are high relative to the movie. You’ve got one chance at the girl you’ve been in love with your whole life.

“U” stands for “Urgency.” I cannot stress enough how valuable urgency is to a story. I’ve told countless writers in consultations to tighten up their timeline with some sort of urgent deadline and their script ALWAYS gets better. Take the example I just used above about a guy trying to win over the girl he’s been in love with for 20 years. Let’s say that this girl is only in town for one weekend. That makes his job infinitely harder than if he has an entire year to win her over.

That’s what urgency does. It doesn’t just make your hero have to complete his goal. It makes him have to complete his goal RIGHT NOW. Next month will be too late. Next week will be too late. Maybe even the next day will be too late. You still have to come up with a ticking clock that’s organic to your story. For example, Mark Watley in The Martian was stuck on Mars for an entire year. But that’s because it takes time for spaceships to get to Mars. But you should make the urgency as tight as the story will allow you to.

The reason you want your GSU set in the first act is because it’s what powers your second act. The weaker your GSU is, the more you’ll struggle in that second act. When writers come to me and say, “I ran out of juice in the second act. I couldn’t think of any more scenes,” it’s almost always because their hero’s goal wasn’t clear enough or strong enough. A hero with a strong goal will always have something to do. Because they will always be taking steps to get to their goal.

Batman has a very strong goal. There’s a dude out there killing people. You’ll never run out of scenes to write with a setup that powerful because the goal is so clear: Find this guy and stop him. By the way, this is why so many movies and TV shows have murderers. Because murders set up such a clear and concise goal: Someone has to find them.

Now there are movies where the GSU is weaker. I’m not saying those movies should never be written. But I will tell you right now, they are way harder to write due to the fact that a lack of GSU equates to a lack of narrative momentum. If characters aren’t desperately pursuing their goal, it means they are either stagnant or reactionary.

Even The Dude (The Big Lebowski), the laziest main character in film history, is active because he has a goal – to retrieve money for the rug two thugs ruined.

If you *are* writing more of a character piece set in the real world and feel that a giant goal would swallow your story up, still try to find SOME GOAL that keeps your character active. Or I promise you, you’ll have nothing to write within 15 pages of the second act. For example, the Apple film, Coda, is about a deaf family who make their living fishing. You could’ve easily written an aimless second act that followed the family fishing, and fishing, and then fishing some more. But instead, they added this goal where the main character, Ruby, was trying to make it into a prestigious art school through singing. That pursuit is what structured the second act narrative.

I can’t stress this enough. A weak second act is almost always the result of a first act that doesn’t set up strong GSU. It should be noted that goals *can change* during a movie. The goal that sets your character off on their journey is not always the goal they must accomplish in the third act. That’s because some movies will start with small goals and then keep throwing things at the hero in the second act that require them to pursue bigger and bigger goals. For example, The Dude starts off trying to get reimbursed for the damage to his rug. But he ends up having to retrieve a giant bag of money after his situation escalated later on. Or, in Star Wars, Luke starts off trying to deliver a droid. But he ends up with a much bigger goal: Destroy the Death Star.

But you should still have as big of a goal coming out of the first act as you can muster.

This concludes the main part of writing your first act. You should’ve written 24 pages by today. You will have written 30 pages by the end of the weekend, which means you’ll be finished. Again, I like first acts to be 25 pages. But since this is a first draft, we want to go a little long, as we’ll get back in there and edit it down next week.

Next First Act Post: Monday, March 21

Pages to write until next post: 6

Pages you should have completed by Thursday: 30 (all of them)

Today we learn the value of writing scenes that KEEP THE READER TURNING THE PAGES

Day 1: Writing a Teaser

Day 2: Introducing Your Hero

Day 3: Setting up Your Hero’s Life

This one is going to hurt.

I want you to take everything you’ve written so far AND THROW IT AWAY.

Okay, okay, okay. I’m kidding.

Sort of.

But mentally, I do need you to cross that bridge, because today’s post is about taking the mundane logical stuff that you’ve written and turning it into something fun and compelling. So far, you’ve been writing for yourself. Now, I want you to write for the reader.

A huge problem with first acts is that there’s so much to set up. You have to set up your four most important characters. You have to set up secondary characters. You have to set up your hero’s life. You have to set up the world your hero exists in. You have to set up the plot. You have to introduce some backstory. You sometimes have to set up rules (like in Source Code, the rules of the loop).

As a result, what a lot of writers do, without realizing it, is they write a first act that sets up all of these things then pat themselves on the back for doing so. Which they should. Setting up a bunch of stuff is hard. But if ALL YOU’RE DOING is setting things up, you’re not entertaining the reader, which means they never made it past page 10.

That’s what today’s post is about. It’s about writing entertaining scenes so that the reader wants to keep reading. What constitutes “entertaining?” Simple. Anything that makes the reader want to turn the page.

You can go about this in a couple of ways. You can write the boring version of all your first act scenes, focusing exclusively on setting everything up, then come back and rewrite each scene with a focus on entertainment. Or you can do both right away. Ask yourself what you need to set up in the scene then ask, how can I do that in the most entertaining way possible?

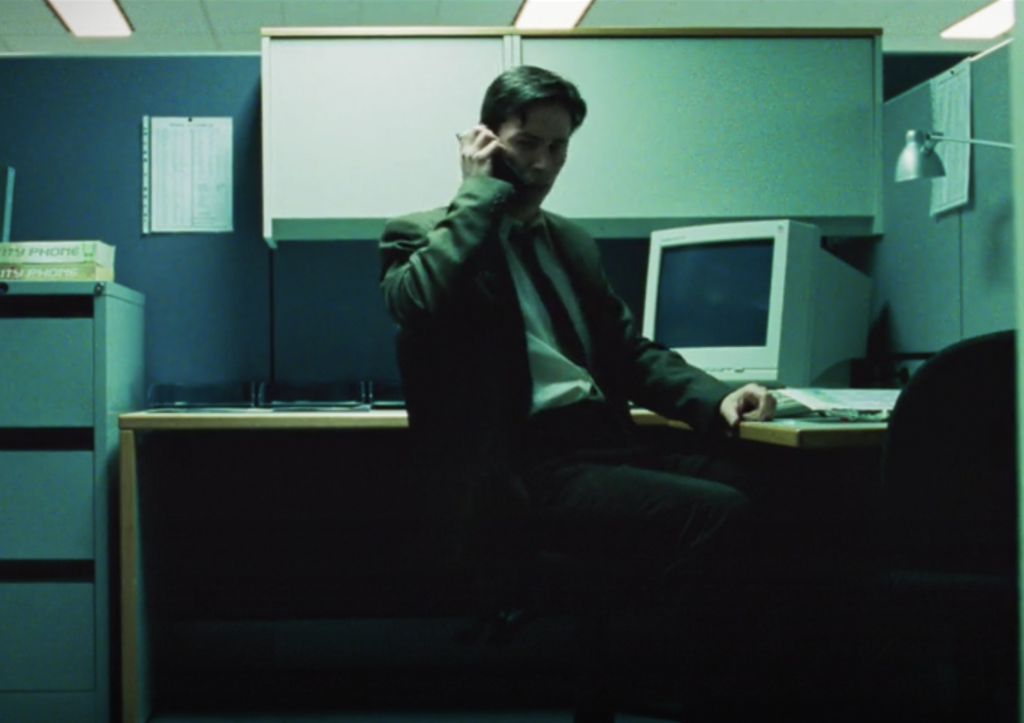

Luckily, we have a prototype film that does this exceptionally. The Matrix. Go watch The Matrix now. It’s free on HBO Max, if you have it. Pay attention to just how entertaining the first act is. Afterwards, you can come back here and look at how each scene not only sets things up, but keeps us entertained along the way.

SCENE NUMBER 1 – TEASER

A teaser will be the easiest scene to make entertaining because that’s the function of the teaser. If your teaser isn’t one of the most entertaining scenes in the movie, I suggest you delete it. In The Matrix, we get Trinity being approached by a group of cops and mysterious men in suits. There’s mystery all over, which makes this a good time to remind you that when it comes to entertaining a reader, mystery is a great tool. Who are these men? Who is this girl who can run on walls and do death-defying stunts? Wait, did she just disappear in that phone booth? What’s going on? A reader isn’t just hooked after this teaser. They’re obsessed.

SCENE NUMBER 2 – WE MEET NEO

This is a scene a lot of writers would’ve tripped up on. You’ve had this giant teaser. You have to introduce your hero in a potentially ‘boring’ scene, since he’s home, by himself. This is, unfortunately, necessary, since we have to establish Neo as a loner, someone detached from the world. But the Wachowskis still keep the scene fun. Neo gets a mysterious message on his computer telling him to “follow the white rabbit.” When a group of partiers come to grab a hack Neo wrote, they ask him to come to the club with them and he says yes. Notice also that since there isn’t a lot the writers could’ve done in this scene (Neo alone in his room), they know to keep it short. If your scene isn’t as entertaining as it can be, shorten it up.

SCENE NUMBER 3 – NEO MEETS TRINITY

Another potentially boring scene. Two characters have to talk to each other. It’s very easy to make talking scenes boring. But here, the mysterious Trinity approaches Neo at the club. She plants some thoughts in his head, such as looking for something bigger. The Matrix. She can help him find it. It’s a short scene that keeps the mystery going. Again, the goal here is to get the reader to turn pages. That’s all we care about. And we want to turn the pages after Trinity, the badass we saw in the teaser, offers an opportunity to Neo to learn about the matrix. The matrix is, in essence, a mystery box. As long as it remains unopened, the reader will desperately want to learn more about it.

SCENE NUMBER 4 – NEO IS LATE

You will not have remembered this scene from The Matrix. But it’s a clever scene from a writing perspective. Let me tell you why. I read this type of scene a lot. It’s the scene where our hero, an office worker, has to talk to his boss about something, usually to set up all the work he has to do. In The Matrix, they use it as an opportunity to push the movie’s theme. The boss explains to Neo that everyone here is part of the whole. Individuality doesn’t work. Here’s the clever part, though, which helps turn a talky scene into something entertaining: Neo is late. So he’s getting scolded by the boss. This changes the tenor of the scene from “I’m setting up my hero’s workplace” to “A dramatically tense scene where my protagonist is being chastised.” It’s a small thing. But this is exactly what you should be doing. You shouldn’t just put two characters in a room to set up information. You have to find the dramatic angle that gives the scene an edge.

SCENE NUMBER 5 – NEO GETS A DELIVERY

This is ANOTHER scene that could’ve gotten boring quickly. It’s the first time we’re seeing Neo at his workplace. Writers could’ve gotten too wrapped up in what Neo was working on or who Neo worked with. The Wachowskis don’t bother with any of that. They have a FedEx guy deliver a confused Neo a package. Neo opens it. It’s a phone. It rings. On the phone is some dude named Morpheus, who informs Neo he’s going to help him avoid the three scary suited guys we saw in the opening scene. This begins a game of cat and mouse around the office that Neo eventually fails. Chase scenes or scenes where your character will have to hide: these situations have entertainment value baked in.

SCENE NUMBER 6 – THE INTERROGATION

The agents have now captured Neo and bring him back to the station, where they have some questions. It’s an interrogation scene that has some tricks up its sleeve to keep things extra-entertaining (Agent Smith makes Neo’s mouth disappear then inserts some sort of device in his body). Half of coming up with entertaining scenes is finding scenarios that do the work for you. Interrogation scenes are always tense so you know the scene is going to be entertaining. But notice how the Wachowskis keep building on the mystery. These strange agents seem to have these powers. They want to track Neo for some reason. There’s no way we’re not turning the page after these reveals. We have to see what happens next. As a comparison, I want you to go to the sixth scene in your script. Read it. Does it make the case that you MUST KEEP READING? If not, you can do better.

SCENE NUMBER 7 – THE CAR RIDE

After waking up and going outside, Morpheus’s team pick Neo up. Before Neo knows it, there’s a woman with a gun pointed at him telling him to take off his shirt. I mean look at how quickly these scenes jump into the good stuff. There’s no mindless dialogue. No setting up boring information we need to know. Each scene seems specifically designed to entertain first, exposition second. Next they pin Neo down and extract the tracker the agents put inside of him.

SCENE NUMBER 8 – NEO MEETS MORPHEUS

This is the most exposition-centered scene in the script so far. But the Wachowskis have done such a good job setting up Morpheus that, as readers, we’re all-in with this scene. Remember, not every scene is going to be entertaining in the same way. A car chase is different from a mystery is different from an argument is different from a suspenseful scenario. Here, the work for making the scene entertaining has already been done. We’ve built up Morpheus and, therefore, are thrilled to meet him. On top of that, we’re still curious what Morpheus wants from Neo, and how this all comes back to the matrix. Still, the Wachowskis look for ways to add even more entertainment. So instead of Morpheus saying, “Follow me,” and walking through a door into the Matrix, he gives Neo a choice, the red pill or the blue pill. It’s always entertaining to watch your hero make difficult choices, so it’s a great scenario to add to your scene. — Of course, after this scene, Neo crosses over into the real world and his second act adventure begins.

I can honestly say that there isn’t a single moment in the first act of The Matrix where I wasn’t invested, where I didn’t want to turn the pages. That’s what you’re aiming for with your first act. Yes, get all the relevant setup in there. But then go to work on every single scene, asking yourself, “How do I make this scene as entertaining as possible?” Think of each scene as its own short movie and you’ll have a head start. Because every movie needs to be entertaining.

If you can internalize this, you will be writing first acts that are tens if not hundreds of times better than 85% of the writers out there. Once a screenwriter learns how valuable even an eighth of a page is when it comes to, potentially, losing the reader, they make it their mission that no reader will ever be bored reading their screenplays again. And their screenplays become so much better as a result.

It’s time for you to make that jump.

Next First Act Post: Wednesday, March 9

Pages to write until next post: 2

Pages you should have completed after today’s assignment: 13

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: A group of illegal time travelers must perform the, quite literally, heist of the century, in an attempt to steal a special time piece that, when operated, will change the course of history.

About: This script sold to Original Films and Paramount recently in a competitive situation. I didn’t realize it when I read “Relay,” but the writer, Macmillan Hedges, wrote a Black List script from a couple of years ago called Cosmic Sunday. So my entire review of this script was written before I went back and found that out. I only bring that up because, if I had known, I would’ve been better prepared for what I read today.

Writer: MacMillan Hedges

Details: 119 pages

Now today’s script is more my speed.

We’ve got time travel.

We’ve got heists.

We’ve got… well, do we need anything more than time travel and heists?

Let’s find out.

When we meet Jack Ledger, he’s stealing something from the past while being chased by his nemesis, Zoey Beckett, a time travel cop determined to take him down. This chase is special because, although they are in a foot race in the 100 year old Bismark Hotel in San Francisco, they are jumping through pockets of time. It’s 1910, it’s 1953, it’s 1969, it’s 1992. We have no idea what’s going on here and, unless you received a 1600 on your SATs, you’ll probably never find out.

Jack is able to escape to 2025 (our present) but his criminal boss, Whitechapel, betrays him, siding with Beckett and sending Jack to prison. Ten years later, Jack is released. And Jack knows why he’s released. It’s so that Whitechapel can track him to all his other time travel buddies so he can put them in the slammer as well!

Jack doesn’t care. He’s got other things on his mind. He wants to break into “the vault,” the basement of the time travel headquarters. It’s there where all the things that have been stolen from the past are being kept, including his “timepiece,” the special thing that allows you to travel through time (I think – more on that later).

To achieve this feat, Jack will need to construct a crew of people throughout time… and some from the present. Or maybe mostly from the present and a couple from throughout time. It’d be cool if they were all from throughout time but since this script was so confusing, I can’t definitively say where everyone was from. The point is, he needs to construct a “Mission Impossible” crew.

Oh, by the way, we’re told how time travel works here. During the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, a fault line was established that reconstructed time and space. Any structure along that fault line can be used to travel back through time. The older the building, the further back you can travel. Which is why really old buildings in San Francisco are so valuable to time travelers.

Anyway, for reasons that are still confusing to me, you can’t just go steal something and bring it back to the future. It’s better if you use the “relay” technique. This is where you set all your crew members in different years, and then have each heist member in the chain give it to a person who then puts it in a pouch, where it is then picked up many years later by someone else, who then puts it in another pouch and hides it for someone 30 years from then, and so on and so forth. We’re told this is done because it’s harder for the time police to catch you, if I’m to understand the rules correctly.

The ultimate goal seems to be retrieving Jack’s old timepiece. Unfortunately, we won’t know why he needs the time piece until the very end. So hold onto your shorts and get ready for one final wild twist!

Today’s script is a giant reminder that when you write time travel movies, they need to be simple. In a way, Back to the Future ruined time-travel movies because they made it look so effortless. In reality, getting these things right is nearly impossible, which is why you have to rewrite them to death. That’s what Gale and Zemeckis did. They rewrote Back to the Future so many times, their typewriters broke.

Nobody does that anymore. As a result, you get scripts like this, which have all these big ideas, but you need an industrial sized shovel to dig all those ideas up and assemble them into any sort of cohesive narrative.

The number one rule of time travel scripts is: DON’T OVERCOMPLICATE THE TIME TRAVEL PART. It’s clear, here, that the Relay rules only make sense to the writer and no one else. I don’t say that flippantly because it’s a mistake all screenwriters have made at one point or another. They write a script with incredibly complex rules and simply assume that because it makes sense to them, it’ll make sense to the reader as well.

Here’s the information we’re given about time travel in the first act. There’s something called a “timepiece” that you must have in order to time travel. I think. I’d say I’m 80% sure about that. But when you steal things in the past, instead of, you know, just taking them back with you, you for some reason have to put them in “time caches.” Little pouches. And then, in the future, you can conceivably retrieve your pouch and retrieve what’s in it.

Except you can’t just create a time pouch in 1910 and pick it up in 2025. You must have someone pick it up in 1930 and put it somewhere else. And then someone else pick it up in 1960 and move it. And then someone pick it up in 1980 and move it. And so on and so forth until we reach 2025.

Anyway, so our hero, Jack, rescues his buddy, Brigance, in 1910. They then jump to 1951. Keep in mind, I was told that you needed a timepiece to time travel and we were told that Jack got his revoked from the time travel police in the opening scene. So they don’t tell us how he is still able to jump back to 1910. They only tell us, in a side note, that “it will be explained later.” I’m serious. That’s an actual note in the script.

So I’m guessing that they jumped to 1951 because Brigance had a timepiece and he used it for both of them? Maybe. Who knows? But, for some reason, despite Brigance being able to jump them to 1951, he can’t jump them any further. For that, they need Jack’s timepiece, which is in a local church that is acting as the time travel police headquarters. I do not think the police have the timepiece in this year, though. I believe it’s still in 2025. Which is funny, cause we then jump to 2025. Except I thought we couldn’t jump to 2025……..

I think you get the idea of how confusing this is. But in case you don’t, here’s a standard line of exposition from the movie: “First we need to acquire equipment, map out each time period in The Upstart, place TimeCaches for each handoff through time and acclimatize to our designated time periods — find the specific moment for each change to the alt. timeline.” And another: “The VaultMaker never worked in The Upstart. But Whitechapel will keep a descendent nearby. As a security protocol. So we need to find that descendent. That’s how we can get access to the vault.”

Not that anyone who’s producing this will listen to me but I am making a promise to the producers of this movie that if they don’t massively – and I mean MASSIVELY – simplify the time travel in this script, this movie will fail. I know this because I have read every single time travel script of significance from the last 30 years. I know which ones succeed and I know which ones fail. And the ones that fail are the ones that have massively overly complicated rules such as this one.

I was so disappointed by this script, I can’t even tell you. I was thrilled when I saw it in my e-mail, particularly after yesterday’s yawner. Finally, we have a cool new script in a genre I like! But within the first ten pages, I knew the script was toast. Literally nothing made sense. All this crazy stuff was happening with no context for how it was happening. It was like watching a really intense dramatic dialogue scene in a foreign film without subtitles. You see that everyone in the scene is really emotional yet you can’t understand a single word they’re saying.

If I take a step back, I think I can understand the writer’s vision here: Let’s make a big time travel heist movie. In theory, I love that idea. And, if I’m making an argument for the script, the writer *is* doing what I tell everyone who writes high concepts to do. He’s creating a story that can only exist inside his movie and no other. The heist here is extremely unique.

But there are very few movies that can work which are swallowed up by exposition. And here’s something it’s pivotal to remember as a screenwriter: You decide how much exposition your script will need when you decide how many rules your script will have. The more rules you have, the more explaining you will have to do. That’s what doomed this script. There were so many darn rules that the characters spent the whole movie explaining them, and even when you’re doing your best as a writer to get all of the rules into the screenplay, it won’t matter if there’s too much to keep track of. I tell this to writers all the time: readers are not robots. We don’t simply download whatever you write. There is a limit to what we can process. And scripts like this stretch beyond our processing limits.

Everything needs to be massively simplified here for it to have a shot at being a good movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Since you will inevitably ask the question, well then how did this sell? It’s the perfect example of the value of coming up with a big exciting concept. If people love your concept enough and want to make your movie, they will overlook weaknesses in your script. And the more they like the concept, the more they’ll overlook. This combined with the fact that The Tomorrow War set off an industry-wide need for big sci-fi ideas, and that’s how we came to this sale.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: Mickey Rourke loses his mind after he’s forced to take a gig on television’s highest rated show: The Masked Singer.

About: This script finished Top 25 on the most recent Black List. Believe it or not, it’s kind of based on a true story. Mickey Rourke really did appear on The Masked Singer (something I did not know when I originally saw the logline) and randomly took his mask off while being interviewed after his first performance, unintentionally (or intentionally?) disqualifying himself. Maybe Mickey didn’t know the rules?

Writer: Mike Jones & Nicholas Sherman

Details: 94 pages

We’ve had a long and winding journey with comedy scripts on this site. The short of it is that 99.99999% of them don’t do well. Even the ones that are funny don’t have enough laughs in them to justify their existence. I’ve long struggled with whether this is more about me having read too many comedies and therefore being numb to overused jokes or if it’s more the fault of the writers, who aren’t delivering.

Well, this weekend’s mini-binge of Peacemaker reminded me that when you have a group of funny characters and a writer who’s good with dialogue, you’re funny, even to people who have read a million comedy scripts before and know what to expect. In other words, no excuses.

Since this was the funniest premise on this year’s Black List, I felt if any script had a shot at making me laugh, it was this one. Let’s find out if I was right.

Mickey Rourke had one hell of a career in the 80s and early 90s. The script lets us know just how good he had it, giving us all the movies he turned down (Bad Boys, The Big Chill, Caddyshack, Dead Poets Society, Platoon, Tombstone, The Untouchables, Pulp Fiction, Top Gun, 48 Hours, Beverly Hills Cop, and Silence of the Lambs).

While Rourke had a brief career resurgence with The Wrestler, that was almost a decade ago. With those mortgage payments on that Malibu five bedroom getting harder to pay, Rourke does the unthinkable – he accepts a job on Fox’s weirdo reality game show, The Masked Singer, which has celebrities dress up in bizarre costumes, sing a song, and then a panel of judges tries to figure out who they are.

When Rourke gets to set on his first day, he falls in love with a big purple gremlin costume, insisting on wearing it. Then, during his first performance singing the upbeat Barenaked Ladies song, “One Week,” Rourke has a breakdown and begins crying in his suit. He continues to sing the song though, now as a slow ballad, and America instantly falls in love with him.

Of course, nobody knows that Purple Gremlin is Mickey. So Mickey can’t capitalize on his newfound fame. When he attempts to extort Fox-Disney for some money, they remind him what they did to Armie Hammer when he was difficult. When Mickey keeps pressing the issue, they recast Purple Gremlin with Wanda Sykes!

Furious, Mickey kidnaps the president of Fox TV and, as Purple Gremlin, livestreams a list of requests that, if Fox doesn’t meet, he will blow her up. After Mickey calms down, he decides against blowing her up, but is able to negotiate his way back onto the show for the big finale. He then gives one of the longest monologues in movie history decrying the death of art. (Spoiler alert) He then refuses to take off his mask. The End.

Screenwriting Trigger Warning: This script is heavy on the asides and fourth-wall breaking. If you are not into that sort of stuff, do not read this script. It may put you in a permanent anger coma.

“The Masked Singer” screenplay is almost as absurd as “The Masked Singer” concept. It’s one-part fourth-wall breaking, one part emotional character study, one part absurdist comedy, and one part thoughtful commentary on the state of the industry. I don’t know what to make of it if I’m being honest. On one page, Rourke is threatening to blow someone up in a purple gremlin costume and, on the next page, Rourke is giving a “Leaving Las Vegas” level exploration of debilitating drug addiction.

One of the things you’re always battling as a reader is how the script you expected compares to the script you actually got. This was a funny concept so I was thinking the script was going to lean into Mickey being a diva. Instead, it leans into Mickey being a sad depressed old man. And my question to the writers would be, “Which one is funnier?” I contend that Mickey being a diva is funnier. So I was miffed that that was scrapped in favor of Sad Mickey.

Ultimately, comedy scripts are judged by whether you laugh or not. And I did not. I suppose I giggled a few times, like at the ongoing joke of Mickey being pathetically sad about the fact that he never had kids. But mostly I read this script with a giant confused look on my face. I couldn’t understand exactly what I was reading.

Some people have called this a “parody” script. It’s supposed to get the writers noticed. It was never meant to be a movie. I call b.s. on that. If Mickey’s agents called these guys and said he wanted to do the film, would they say ‘no?’ Of course not. Therefore, it’s a legit script. I bring that up because some writers try to hide behind the parody label so they can have it both ways. If it’s made fun of, it was never supposed to be a real script anyway. And if it gets made, it’s a great story about how a script that wasn’t even real got made.

But ever since Being John Malkovich got produced, these celebrity-focused screenplays are legit scripts and need to be judged as so. While I didn’t dislike this script. I found it too messy. It’s trying to do too many things. Trying to cover too many bases.

And we can’t forget that these scripts have a ceiling. They do well with lower-tier readers, people who haven’t read many scripts, because this is probably the first time they’re encountering this style. But when the scripts move up the ladder to the seasoned readers, there’s a lot of eye-rolling that goes on because they’ve seen this act before. Probably dozens of times.

What’s so frustrating is that this is a really funny idea. An actor who takes himself more seriously than most world leaders is forced to accept the most humiliating job in show business – The Masked Singer. There’s so much comedy to mine from that.

But the focus is more on the fourth-wall breaking description (talking directly to the reader) than the script itself. When you have a good concept, you don’t need that. That’s what good concepts give you. They make it so that you don’t have to depend on gimmicks. You should only bring in gimmicks when the concept is weak.

Take one of my favorite comedy concepts of the last decade, Neighbors – A young couple who have just started a family find out that they’ve moved next to a fraternity house. Imagine writing that script in a big wacky voice where you’re constantly talking to the reader. It would’ve distracted from the story, right? Yet that’s what’s happening here.

The final issue is the script tries too hard. The writing really wants you to love it. I’ve always struggled to figure out where the “try-hard” line is. How does one be big and boisterous with their writing and it not sound try-hard? Well, Peacemaker just did it. So I know it’s possible. But there definitely seems to be a line and, unfortunately, The Masked Singer crossed it.

Based on the overcooked writing and uneven tone, this one wasn’t for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In a comedy script, you should never try and make the asides funnier than the jokes in the movie itself. Your funniest stuff should be coming through great dialogue or a clever payoff or a hilarious set piece. It shouldn’t come from you sharing an off-screen opinion about whether Nick Cannon should be in your movie after his anti-Jewish comments or if Donald Trump is soulless. Save your best jokes for the actual movie, the stuff that audiences are going to see.