Search Results for: the wall

High-profile television IP is a fairly new space so I suspect we’re going to be scratching and clawing our way into a workable structure for these shows for the foreseeable future. What I do know is this. Marvel shows have been average. And the Star Wars shows have been below average. Boba Fett’s latest episode confirmed to me that they don’t know what to do with that character or the story, for that matter. The show has little bursts of fun moments. But, for the most part, it’s a show in search of a coherent story.

The Marvel shows have fared a little better. Hawkeye and Falcon & Winter Soldier were no-frills empty calorie entertainment. And Wandavision and Loki, while better, never quite lived up to their ambitious objectives.

One of the things I’ve realized is that superhero characters are built for big flashy moments. The caravan chase in The Dark Knight. The train sequence in Spider-Man 2. The airport sequence in Captain America: Civil War. TV doesn’t allow for this to happen. The budget just isn’t anywhere near what it is for those films. That’s where superhero shows have struggled. With their identity stolen away, they’ve tried to reinvent the genre. And what we’re learning is that there isn’t anything low-budget that can replace those big crazy set-pieces.

Which brings me to Peacemaker, easily the best high profile television IP that’s hit streaming so far. I went into the series skeptical only because I didn’t think Gunn’s Suicide Squad was very good. I did that thing where you put a show on in the background while mindlessly looking up new coffee tables online. Despite only casually following along, I found myself consistently giggling at the dialogue.

The next thing I knew my laptop was on my current ugly coffee table, completely closed (a rarity) and with each passing minute, I was more pulled into Peacemaker’s charming irreverent slice of superhero fiction. You know what it reminds me of? If Community was an R-rated superhero show. It’s got that balls-to-the-wall “who cares” attitude to it.

Hell, I was singing along to the opening dance number by the second episode!

There are a lot of things to like here but I’ll point out a couple that stood out. The first was the bridge between episodes 1 and 2. At the end of episode 1, Peacemaker is being chased by a scary powerful alien woman. That’s the end of the episode. The second episode 2 begins, we cut to the continuation of Peacemaker being chased by the alien woman!

You might be asking, “Why is that a big deal, Carson?”

Well, whenever I watch an episode of Boba Fett, they draw EVERRRRYYYYTHING OUUUUUUT FOR AS LOOOONNNNNNNNG AS POSSSSSSSIBLE. If we’re in the middle of a chase at the end of an episode, you can bet your bottom dollar that the next episode is going to start with a 20 minute flashback. And maybe – MAYBE – they’ll show us the continuation of the chase after that.

Don’t get me wrong, I know this is a narrative technique. You give us the beginning of a big moment then you cut to other characters or other storylines so we have to suspensefully wait to see what happens. However, it’s clear with episodes of Boba Fett, and most of these Marvel episodes, that that’s not the reason they’re making us wait.

They’re making us wait because they don’t have enough story. And when you don’t have enough story, you lean on trickery. You lean on false story engines. You’re basically finding things that fill up time so you can make the episode’s minimum time requirement.

This has become so predominant in high profile IP shows that I was legitimately shocked – in a good way – when we continued right where we left off in episode 2 of Peacemaker. Gunn understands that the lure of flashbacks – they help flesh out characters – can also act as story roadblocks, sending you off on some long not-well-thought-out detour that always takes too long to get you back to your original route.

Good writers develop characters in real-time. They don’t need that flashback crutch.

The other thing I like about Peacemaker is that Gunn didn’t say, “What’s the best Peacemaker show?” He said, “What’s the Peacemaker show that would best highlight my strengths as a writer?” Gunn’s biggest strength is putting characters in a room talking about nothing. As many of you know, I’ve railed against doing this. But IF YOU’RE GREAT AT SOMETHING then it doesn’t matter if you’re not supposed to do it. Your strength should always take precedence over what you’re “supposed” to do. And Gunn is a master at funny observational dialogue.

I’m beginning to realize why I didn’t like his last two movies (Suicide Squad and Guardians 2). It’s because, in features, you can’t sit characters in rooms and have them babble on for three minutes. Every scene in a feature has to push a ten-ton movie forward. Without that constraint, Gunn can now let loose. And he’s really good at letting loose. The way his mind works is so funny and he’s finally found a medium that allows him to go to town in this area.

By the way, one of the reasons he’s able to do this is because he’s created eight full-on dialogue-friendly characters. If you’re new to my site, there are dialogue-friendly characters and dialogue-unfriendly characters. If you’re trying to write great dialogue with two dialogue-unfriendly characters, it’s never going to sound right. I mean, can you imagine Boba Fett and Fennec having even a single entertaining conversation together? Of course not. Because neither of them is dialogue-friendly.

Gunn made sure that every single character here had their own entertaining personality type. Peacemaker is a blabbermouth who says a lot of ignorant things. His hilarious best-friend, Vigilante, is like Deadpool-lite. Co-team leader Emilia is always angry and always ready to take that anger out on you. Tech Specialist John, probably the most introverted of the bunch, is still willing to engage in awkward opinionated debates about what they should be doing. New Girl Leota isn’t afraid to throw quippy insults Peacemaker’s way.

I know it seems obvious. But if everyone is designed to be entertaining when they speak, you’re going to have a lot of good dialogue.

But I’ll tell you my favorite moment in Peacemaker – the moment that confirmed to me the show was special. And, believe it or not, it’s a moment that doesn’t have any dialogue. It occurs when Peacemaker is hiding outside the house of a man they need to assassinate with Emilia, his hot-headed boss who hates him but who Peacemaker has a major crush on.

They’re far off, in the bushes, waiting for the target to arrive so they can take him out with a sniper rifle. As they sit in silence, waiting, Emilia is eating a bag of trail mix. Peacemaker keeps looking over at it, hungrily. Finally, reluctantly, she holds the bag out so he can have some. He eagerly reaches in and takes a handful. Then, just as we think he’s going to start eating it, he begins to pick out the little pretzels and, one by one, place them back in the bag that she’s holding while she stares at him like he’s a crazy person.

I like this moment for two reasons. I love scenes that tell us who characters are by showing and not telling. This twenty-second moment tells us so much about these characters without saying a word. She hates this guy so much that the act of giving him her food must be coupled with an animated production of how much she hates doing so. Through that simple action, we know how much she detests Peacemaker. Meanwhile, the fact that Peacemaker starts placing trail mix pieces he doesn’t want back in her bag tells us that he is so ignorant to others’ perceptions of him that he doesn’t even know when someone hates him. That is Peacemaker in a nutshell: oblivious.

And two, most writers wouldn’t think to come up with this moment. It’s too subtle. To know your characters well enough to create a subtle moment as specific as this one is rare. Or, at least, in the scripts I read, it’s rare. It’s a great reminder to think about what your characters could do while they’re not speaking to each other. Moments do not always have to start with words.

This show came at just the right time for me. I’ve been looking for a good show. And this one is so fun. I would go so far as to say it’s the best thing James Gunn has ever done. And I dare anyone to challenge me on that because I’m obviously right. What about you? Have you seen Peacemaker? What did you think?

In my continued efforts to help you write a script that gets you noticed by the industry, I keep going back to this idea of “voice.” Second only to coming up with a killer concept, writing a script with a unique voice is a great way to a) get an agent, and b) make the Black List.

The problem with giving writers this advice (“Improve your voice!”) is that they don’t know what “voice” is. How can you practice getting better at something if no one’s able to define it? That’s one of my ongoing pursuits here at Scriptshadow – quantifying what “voice” is so writers can get better at it.

For starters, don’t get writing voice mixed up with directing voice. Directing voice is [mostly] the way a director manages the images and sounds of his movie. Terrence Malick having all those wide-angle “follow” shots of his characters, over flowery voice over and an intense music track. That’s not writing. That’s directing.

Writing voice has to do with the way you describe things, your dialogue, your humor, what aspects of the story you choose to focus on, how sparse or thick your writing is, how flowery your prose is, how much of your personality makes it into the writing, and what the overall thematic focus of your story is. A strong voice results in people being able to know that you wrote a script without your name having to be on it.

Hence, I’ve gone through a bunch of movies and screenplays to determine every type of voice out there. And I came up with ten. We’re going to go through all ten of these and, afterwards, I want you to ask yourself which one sounds the closest to the way you write. Then I want you to consider writing a script in that voice.

Although I still contend that a great movie idea beats everything, the goal here is to get yourself into the game. And if your ideas haven’t generated a lot of interest on the screenwriting market, then “voice” may be the better way in. Okay. Are you ready? Let’s get into it.

Voice 1 (Snappy Dialogue): This is probably the most popular version of “voice.” It’s the snappy clever dialogue script. It’s Juno. It’s The Breakfast Club. It’s The Social Network. This class of voice is reserved for people who are gifted in the art of dialogue. The characters are all smart and have great comebacks to whatever the other character says. There’s an effortless lyrical quality to the exchanges. You never quite know what anybody’s going to say next. Big balmy monologues come effortlessly to these writers. Just remember that in order to write snappy dialogue, you need genres and situations that support snappy dialogue. Don’t write thrillers or horror or sci-fi if you want to write in this voice. Write in genres where there’s naturally a lot of talking.

Voice 2 (An Elevated Dark Sense of Humor): For whatever reason, “regular” humor doesn’t get you the “great voice” label. As good as The Hangover was, nobody categorized the writers as having a great voice. When it comes to humor and voice, you have to go dark to make an impression. Some of you were pointing out that Tuesday’s script, Wait List, would qualify as dark humor. Three Billboards Outside Ebbing Missouri is a recent high-profile script that we’d place in this category. I’d put Get Out in there as well. Possibly Nightcrawler. The reason I say “elevated” is because just having a dark sense of humor isn’t enough. There has to be a level of intelligence behind it. It has to be clever, cunning, biting.

Voice 3 (Saying What You’re Not Supposed To Say): One of the key tenets of “voice” is that you give the reader something they haven’t seen before. That’s why your script stands out. It’s providing the reader with a new experience. When you say things that you’re not supposed to say, you’re giving the reader something that they don’t hear. This is what separated Louis C.K. from so many other comics. He started talking about how idiotic his kids were – a huge ‘off-limits’ topic for comics. But because there was truth to what he was saying (a lot of parents secretly felt their kids were idiotic), they loved it. It was choices like this that make him such a unique voice. On the movie side, we can tweak it a little to explore things that you’re not supposed to explore. American Beauty became a gigantic hit in part because a 40 year old father was pining after his high school daughter’s best friend. You’re not supposed to write about that. But it’s because nobody else is writing about that that doing so makes you unique.

Voice 4 (Going Super Dark): There’s a floor to how low general audiences are willing to go. The super-dark voice is when you plunge a hammer through that floor and jump down into whatever’s beneath it. The most famous example of this voice is Seven. That script got a ton of attention specifically because it was so dark. A more recent example would be True Detective. I might even put Promising Young Woman in there. You want to figure out where the average person’s threshold is and push past that. I would actually put the now secretly famous Osculum Infame in this category. The risk with these scripts is that they will offend some people. So you might receive some uncomfortable rejection e-mails. I know I did with Osculum Infame. But when someone likes it, they tend to really like it.

Voice 5 (Mixing Genres That Shouldn’t Go Together): This one is how Tarantino got famous. He came up with his own genre – the “Tarantino” genre. He did this by mixing Westerns with Blaxploitation with Black Comedy with Noir with Crime Drama. Clearly, when you do this, you’re going to come up with something that feels different. Remember back in 2010 when writers started mixing history with horror? We got Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. We got Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter. You can play this game any way you want and come up with some wild concepts. You could mix Westerns and Musicals, Sci-Fi and Black Comedy, Romantic Comedy and Fantasy. You use any of those combinations and you instantly get tabbed as having a unique voice.

Voice 6 (Full Weirdo): This is when you throw out any pretense of writing a Hollywood movie and just write something WEIRD. The Lobster comes to mind. Sorry to Bother You. The Lighthouse. Swiss Army Man. For both the concept and execution of these scripts, turn off the logical side of your brain and let the right side do all the work for you. The weirder you get, the more voice points you earn.

Voice 7 (Put Your Stake In A World People Aren’t Writing In): When I read Taylor Sheridan’s stuff, I’m not sure any specific voice jumps off the page. However, I always know when I’m reading a script of his, which is one of the components of a “voice” script. What I realized is that Sheridan found this universe that everyone else was ignoring and staked a claim in it. Americana. Struggling Middle Class America. Conservative values. He then treated that world with sophistication, whereas everyone else was writing really cheesy movies in that space. There are writing landscapes out there that people are ignoring. Go out there and find them and you can become the voice of that world.

Voice 8 (Quirk It): Twenty years ago, a movie called Little Miss Sunshine burst onto the scene and became the little movie that could. It was, maybe, the quirkiest movie ever produced. And it started a movement. Quirk was in. “Quirk” is any idea that’s weird, goofy, and leans into awkwardness instead of avoiding it. The voice here comes from the characters who will all be playing outsized versions of their real-life counterparts. The character will never just be depressed. He’ll be the depressed guy who’s made a vow of silence and only speaks with his hands. Garden State, Ghost World, Safety Not Guaranteed. All quirk-fests. And yes, I know Juno could be placed in this category. There is going to be some overlap between voices. Don’t get too caught up in that.

Voice 9 (The Gimmick Script): The Gimmick Script is less about the movie and more about the reading experience. The Gimmick Script might be written in first person. There might be a lot of breaking the fourth wall (with the writer speaking directly to the reader). The prose may have a lot of needless swearing in it, or asides that have nothing to do with describing what’s going on. It may take a well-known property and flip it on its head (Exploring the Charlie Brown characters all grown up). One of the first scripts that made my Top 25 was called “Passengers,” (there’s a link to it over on the right panel), a weird alien invasion story told in the first person. Gimmicky voice is probably the cheapest type of voice available to writers. But it can work.

Voice 10 (Create Your Own Style by Mixing and Matching): It’s important to understand that voice is always evolving. You can create a new voice at any time. Shane Black wrote big fun masculine movies with sparse playful prose that he sometimes broke the fourth wall on. That was his style. Just remember that your voice is, ultimately, your personality. So pick the “voice modules” that best reflect your personality. That way, you’re writing organically as opposed to forcing it. And that’s it, folks. I hope this helped!

Let’s see if you learned anything. Here are ten movies. Do these movies have a writer’s voice or no? Leave your answers in the comments. In a little bit, I’ll provide the actual answers.

Die Hard

The Hurt Locker

Birdman

Inception

Dune

Ghostbusters: Afterlife

Free Guy

Old

Napoleon Dynamite

Alien

Genre: Horror/Slasher

Premise: When a new Ghost Face copycat killer starts piling up a fresh body count, the local teenagers realize that in order to survive, they’ll need to call on the survivors from the original Woodsboro murder spree for help.

About: Scream 5 has been getting some surprisingly active buzz on the internet. There’s a lot of talk about ‘shocking things’ that happen in the movie. It rode that buzz to a 4-day holiday weekend take of $36 million dollars. That’s pretty good considering the movie only cost $25 million to make. With Wes Craven passing away, the newest Scream was directed by Matt Bettinelli-Olpin and Tyler Gillett. The script was written by incredibly successful spec screenwriter, James Vanderbilt (White House Down, Murder Mystery) as well as relative newcomer, Guy Busick (Ready or Not).

Writers: James Vanderbilt and Guy Busick (based on Scream by Kevin Williamson)

Details: 115 minutes

Some of you may have seen the big fat title of this post and thought to yourself, “A Scream movie? Why is Carson reviewing a Scream movie?”

The answer is simple.

Scream remains one of the greatest screenwriting success stories of all time. And I know what you’re thinking. “Scream?? A screenwriting success story?? Has Carson added magic mushrooms to his diet?”

Yes, I have. But that has nothing to do with this review. You see, here’s what happened. Kevin Williamson sold Scream as a spec. And then, when it was made, it was a monster surprise hit. The opening scene in particular (still one of the greatest opening scenes ever written) blasted itself into popular culture.

But it wasn’t so much the movie that was Kevin Williamson’s success story. Williamson had been trying to make it as a screenwriter for forever in Hollywood. So he had all these failed scripts before Scream. And because Scream was such a hit, everybody in town all of a sudden wanted a Kevin Williamson script. They didn’t care if those scripts were bad. They wanted that name. And so Williamson gave them script after script at the bottom of his hard drive, all of which were average to not good. We got I Know What You Did Last Summer. The Faculty. Teaching Mrs. Tingle. And there were a bunch of others that didn’t get made. Williamson got SO MUCH MONEY from these sales.

So, you see, the reason I’ll celebrate Scream whenever I get a chance is because it’s a great example of there being a light at the end of the tunnel. All that hard work you’re going through as a screenwriter – all of those failed scripts – one day, when you break through, someone’s going to want those scripts. It’s a reminder to never give up!

Which is funny because I heeded that message while watching Scream 5. “Don’t give up, Carson. Keep watching til the end!”

JUUUSSSST KIDDDDDDING.

Kinda.

Scream follows a girl named Sam who, with her new boyfriend, Richie, head back to Woodsboro where her estranged sister, Tara, was recently attacked by a new Ghost Faced killer. That’s what happens in Woodsboro, by the way. Every few years, a Ghost Face killer copycat pops up and starts calling people on phones, giving them life or death movie trivia.

What we learn is that New Ghost Face Killer likely attacked Tara to lure Sam back into town. She’s his real target. Sam, understanding that this is above her pay grade, heads over to local legend and former sheriff, Dewey’s, trailer. After a charged speech, Dewey decides to help her take down New Ghost Face.

Dewey quickly gets the gang back together, calling up ex-wife Gale and the Scream final girl herself, Sidney, to come back into town and help her (spoilers follow). But soon after they get there, Dewey is killed by Ghost Face. Realizing that sh*t just got real, Gale and Sidney make a pact to help these kids take Ghost Face out.

The big showdown takes place at a house party, where the killers (yes, two, this is Scream remember) reveal themselves. Their plan, if you can call it that, has something to do with how the fictional movie franchise within Scream, called “Stab,” has made some terrible movies lately, so they want to provide some real-life inspiration to put the franchise back on track. Lots of killing hijinx then ensue. The End.

Houston, we’ve got a problem. That problem is the wimpifying of Hollywood. Scream 5 starts with a new variation of the famous Drew Barrymore scene from the first film. Tara answers the phone and Ghost Face makes her play a movie trivia game to save her best friend’s life.

The scene is okay. But that’s not what I want to discuss. What infuriated me was that Tara SURVIVES. She survives being brutally stabbed a dozen times. And it just made me sad. Because it shows just how terrified Hollywood is of doing anything remotely offensive. Part of what made that original Scream opening scene so great is that it was brutal and final. If Drew Barrymore survived, nobody would be talking about that scene today.

I started giving more thought to this after the recent Boba Fett debacle. Boba Fett is a crime lord. Killing is in his job description. And, yet, when the mayor’s secretary attempts to pull one over on him and race off, Boba Fett’s punishment amounts to a harsh talking-to.

Why are we afraid to kill fictional people all of a sudden? I suspect it has something to do with this newfound fear Hollywood has of being yelled at on Twitter. It’s just bizarre to me. The second Tara was announced as alive, I rolled my eyes and knew the movie was done. I knew the next 90 minutes couldn’t possibly be good. Because how can you write a good movie if we already know, after the very first scene, that you’re never going to do anything risky? That’s the whole reason the original Scream did well. It took chances.

Another issue was the odd tone they chose to frame the story within. Scream, I guess, is now a sad drama as opposed to a fun horror slasher flick. The music was slow. There were a ton of slow scenes with people in rooms talking. We must’ve been in the hospital for 20 minutes at one point. A sad scene where two sisters talk about their past. Then a sad couple talk. Then a scene where sisters and boyfriend all talk about more serious stuff.

What was so great about Scream is that it had ENERGY. Every scene was charged. It was like each scene took speed right before it was time to shoot. I’m going to go ahead and assume this had something to do with Wes Craven. He cast that original movie perfectly. More importantly, he must’ve tested the kids together to make sure they had great chemistry. Because they all felt like they really knew each other.

Here, there wasn’t a single scene where the kids riffed off each other. They seemed like they all met yesterday. They never looked comfortable. They all seemed to just wait for their lines as opposed to engaging and reacting to one another. Go back and watch that first film because it’s really good and the characters/actors all felt like real friends. And this director didn’t seem to understand how to do that.

Every movie franchise has the thing that it’s known for. And Scream’s thing is its excessive self-referentialism. It loved to make fun of horror movies, lean into cliches, and break the fourth wall.

Scream 5 tries to do that, most notably with its discussion about the “Re-quel.” A requel, as they point out, is a combination between a reboot and a sequel. It’s Ghostbusters. It’s Halloween. It’s Terminator. It’s Star Wars. And what they concede is that it’s impossible to get a requel right because while one foot is trying to move the story forward, the other is planted firmly in the past.

It’s an intelligent assessment of Hollywood’s newest obsession. But here’s the problem: they don’t solve it. They accept it then thrust their story into the exact same problems. You’ve got the new kids participating in a showdown at a house party while Sidney and Gale, our two OGs, become keystone cops, discreetly hiding trackers on cars so they can find the party and take down the killer Scream 1 style.

It’s a mess.

And I’m not going to throw all of the blame on the writers because I’m not convinced you can write yourself out of the problems a requel creates. It’s hard enough to create a good story that has no limitations. Once you tell me I have to find ways to include 50 year olds with kids and marriages and careers in a movie about teenagers who like to get high and hook up… you’re never going to be able to write something satisfying.

The final disappointment with Scream 5 was that I heard the third act was supposed to be great. So much so that they were begging audiences not to share spoilers. I now know that these public cries not to give away spoilers are, simply, marketing gimmicks. Nothing crazy happens in the third act. It’s just your average “everybody tries to kill each other” finale. A final nail in the coffin for the film.

While Scream 5 wasn’t very good, I continue to see the franchise as a symbol to screenwriters everywhere for what’s possible. Write a high-energy entertaining script in one of the five marketable genres (horror, sci-fi, action, thriller, comedy), sell it, then reap the rewards of the buzz by selling all the other scripts on your hard drive.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Understand the type of film you’re writing and make sure you’re delivering that film. We’re all trying to create compelling characters with compelling pasts and interesting flaws that they have to overcome. But if you’re writing a fun slasher movie, 60% of the movie can’t be characters in rooms having sad conversations over depressing musical scores. You need the fun interactions between all your teen characters. You need the fun killings. You need energy. Scream 5 had numerous problems, but the choice to slow down the script to the point where it became a character drama went directly against the DNA of the original film, and therefore killed the movie.

I don’t think there’s ever been a time in my life where I’ve understood the movie industry less. It used to be that you’d buy a script, make the movie, release the movie, and if it did well, the movie was celebrated and everyone associated with it benefitted. If it did poorly, the movie was mocked and everyone associated with it got docked a few Hollywood credits.

These days, who knows what’s going on. There is a freaking Leonardo DiCaprio movie that can be seen over on Netflix right now *FOR FREE*. And yet, as of yesterday, more people would rather watch a film nobody’s heard of called “Stay Close,” which may or may not be a sequel to another movie nobody’s heard of called, “The Stranger.”

You’ve got an Academy Award winning screenwriter who just debuted a movie over on Amazon Prime, also for free, that has such a low profile that, up until yesterday, I thought it was called, “Keeping up With the Ricardo’s” (it’s actually titled “Being the Ricardos”). The industry has been flipped on its head.

This weekend, Hollywood debuted one wide-release film, a female ensemble spy flick called, “The 355.” Had they simply added a decimal after the “3,” they would’ve predicted its first week box office (4 million). It’s a telling moment for the industry, which just a couple of weeks ago, saw a movie land the third highest box office opening of all time in Spider-Man.

The message audiences are sending is clear: “Unless it’s got capes in it, we don’t want it.” When your clientele tells you they no longer like the product you’re giving them, you have to adjust.

One of things that Hollywood has always been good at is marketing. They know how to market anything, even serious films. They’ve learned that if they position a film late in the year and get some key critics to call it incredible, then promote a great performance or great writing or outstanding directing, and throw up a few “For Your Consideration” ads, they can influence enough people into believing it’s a ‘must-see’ experience.

To their credit, the system has helped a lot of good films that, otherwise, wouldn’t have been noticed. I’ll never forget how Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire was originally going to be a straight-to-DVD release until they decided to position it as an Oscar contender. Audiences then fell in love with it.

But this system has also promoted a lot of weak films. Nomadland is a good example. It’s not a good movie unless you’re the type of moviegoer who can have an in-depth conversation about the French New Wave movement. But the machine had to promote something and there weren’t any good “somethings” so they went with Nomadland.

This seems to be happening more and more lately.

Mank, Minari, Sound of Metal, Marriage Story, Vice, Roma, The Post, Ladybird, Call Me By Your Name, Darkest Hour, Manchester by the Sea, Phantom Thread, Fences, Moonlight, Brooklyn, and the list goes on. These are boring-to-decent movies that were overhyped enough that they attained a higher reputation than they deserved.

Now I’m sure some of you are saying, “Carson. You’re wrong! I liked [insert title from movies listed above]!” I’m not saying nobody liked these movies. I loved Parasite. I thought it was a great film. But I’m not going to argue with my non-industry friends when they say, “I don’t care how good it’s supposed to be. I have no interest in watching a Korean movie with sub-titles about class warfare.” General audiences don’t care about these films and the reason that matters in 2022 is that the industry is shifting and serious movies will be left behind if they don’t change their strategy.

The Golden Globes isn’t getting televised this year. AFI is postponed. Same with Critics Choice. Palm Springs is canceled. And The Academy Awards itself, because it’s been promoting weak films for the last half-decade, keeps losing viewers. The system doesn’t work anymore. So what do they need to do?

They need to do the indie version of what Marvel did. Marvel realized that they could expand their market if they cannibalized other genres. They’d give you a big tentpole summer movie experience along with some comedy. Along with a buddy cop film. Along with a spy movie. This is what the indie/Oscar movie market needs to do in order to survive. Unless they’re okay with 20,000 views on Amazon Prime.

The new strategy – give us adult movies that actually serve to entertain rather than try to win awards. Have you ever been to a bar and seen the guy who’s trying to be cool next to the guy who actually is cool? There’s a false bravado to the poser. There’s an underlying need to be liked. There’s a fakeness to his act that everybody sees through. That’s what movies that are trying to win Oscars come off like. They remind us of the guy at the bar who’s trying to be cool. We can all see that there’s nothing beyond the exterior.

If you want serious movies to be big again and to compete with superhero movies and to start making more than 30 million dollars, you need them to be GOOD MOVIES FIRST and awards contenders second.

The prototypical version of this is Silence of the Lambs. A serious movie that cared about entertaining us first and winning critics over second. The Wolf of Wall Street is another good example. Life of Pi, District 9, Slumdog Millionaire, The Departed, Gladiator, American Beauty, The Sixth Sense, Saving Private Ryan. The common denominator between all of these films was that they were serious adult films that prioritized entertaining people rather than preaching to them or trying to win a statue.

These days we get Promising Young Woman. And don’t get me wrong. I loved that script. But I’ve never met anyone outside of Hollywood circles who’s even heard of that movie, much less seen it. They just don’t care. And if the industry wants these people to care, get off of your own self-absorbed asses and start entertaining us. Make a movie that’s good. You have the capability to do both. You don’t have to bore us to death with Moonlight to win awards AND make money.

So like they always say: “What are you going to do about it, Carson?” Keep sitting around and complaining on your little blog? Or are you going to try and change it?

I’m going to change it.

As you know, I have my Fabulous First Act Contest coming up. Starting March 1st, I’m going to guide you through writing the first act of a new screenplay. The idea is that a lot of people are afraid of starting a screenplay because they have so much trouble finishing them. With this contest, all you have to do is write a first act. And, even better, I’m going to be coaching you through writing that first act. So you’re for sure going to finish and, if you want, enter it into my contest (details on entering will be published on April 1).

Anyway, since your chances of winning go up exponentially with a better concept, I want you to have the best concept possible ready by March 1. I’ve been seeing all types of concepts via my logline service (just $25! carsonreeves1@gmail.com) and I keep seeing similar mistakes being made over and over again. So here are five tips you can focus on for a better concept.

1) Make sure it’s a movie you would go and see – I can’t tell you how many writers send me ho-hum loglines and I’ve asked them, “Would you go see your movie?” And they always say, “Of course I would!” I would then ask them if they’ve seen a specific recent movie that’s similar to theirs. These are usually movies that have bombed because, again, they’re based off of weak concepts. Without hesitation, they say, “No.” “Well, why not?” I ask. “I don’t know. It just didn’t look interesting.” I then wait for them to understand the ramifications of what they’ve just said. But they never get it. They’re under the impression that, even though their idea is similar to a movie that nobody wanted to see, their version of the idea is, somehow, special, and people will want to see it. If you have no interest in paying to see movies similar to the one you’re writing, that’s a good indication you’re writing an idea people won’t be interested in.

2) Strange Attractor – I’ve been reading a lot of loglines lately without a “strange attractor.” The strange attractor is the element of your logline that makes it special, that makes it unlike other movies out there. Some people might even define it as “the hook.” Here’s an example of two loglines in the same genre. One without a strange attractor and one with. “After hearing rumors of zombies in town, a farming family holes up in their house for the night.” “A family must learn to live in complete silence after the world has been taken over by aliens that hunt through sound.” Zombies alone are not a strange attractor just as aliens alone are not a strange attractor. You need that extra element – hunting through sound, a family that must exist in silence – to make it a true strange attractor. The strange attractor is, I’d say, a necessity in a logline. It’s hard to get excited about a logline without one.

3) A character can be a strange attractor – Not all of us are interested in writing genre movies. Which is fine. But if you’re not writing genre movies, then you better have an amazing character who sounds interesting in a logline. They, then, become the strange attractor. “Alan Turing, an autistic gay man who would go on to become the father of the general-purpose computer and artificial intelligence, attempts to decode the mythical “Enigma” machine that the German army used to send encrypted messages during World War 2.”

4) Make sure there’s a healthy dose of conflict in your concept – Without conflict, a concept is just an idea. The conflict is what makes it a movie. So, for example, if I said to you I have an idea about a guy who realizes he’s a computer generated character in a video game, that’s still not a movie idea because you haven’t introduced the conflict yet. Now if you tell me that a computer generated character realizes he’s in a video game, starts to take over the game, forcing the game creators to try and kill him (Free Guy), now you’re forming an actual idea. The conflict is the bridge that helps the concept cross over from just an idea to an actual movie.

5) Be as specific as possible – I’d say that, roughly, one-third of the loglines I receive end with a general directionless phrase. “…until she doesn’t know what’s real and what isn’t.” “…causing him to question his life.” “…begins to see that not everything is what it appears to be.” These scripts almost always fall apart because there is no defined goal for the main character. They’re not trying to solve a murder. Or attempting to graduate college. Or trying to win over the guy of their dreams. A logline needs that clear defined path for the main character for it to sound enticing. Like above, with The Imitation Game. Alan Turning is trying to decode a machine to stop the Germans in World War 2. That’s so much better than, “Alan Turing attempts to decode the German Enigma machine, discovering along the way that, in war, there are no clear-cut answers.” Do you see how wishy-washy and generalized that ending is? That’s what we want to avoid.

I’ll have more conceptual tips for you as we get closer to the March 1. In the meantime, run with these!

Today’s script is Joker meets The Social Network meets The Wolf of Wall Street

Genre: Biopic

Premise: The completely outrageous and completely true story of “pharma bro” Martin Shkreli — from his meteoric rise as wunderkind hedge fund manager and pharmaceutical executive to his devastating fall involving crime, corruption and the Wu-Tang Clan — which exposed the rotten core of the American healthcare system.

About: This script finished in the top 5 of the recently released Black List, a list that tabulates development execs’ favorite scripts of the year. The script was written by Andrew Ferguson. Andrew had one script he put up on the Black List amateur site a couple of years ago that readers of that site enjoyed called Boost. The logline for that was: “Two safecracking sisters are recruited for a heist by the Corsican Mafia in order to establish a modern-day French Connection.”

Writer: Andrew Ferguson.

Details: 120 pages

You may be wondering why, of all the scripts on the new Black List, I’m reviewing a biopic. The answer to that question is the same answer to the question of, “What makes a good biopic?” A lot of writers get this wrong so I want you to pay attention. Biopic writers believe that what makes a good biopic subject is a famous person they like. That’s the only criteria they use. But today’s writer knows the correct answer to this question, which is, “Write about the most interesting person you can find.”

Because remember – biopics are inherently boring. They just are. They’re meat and potatoes bland narratives that take us through years and years of a person’s life, making it hard to jumpstart any sort of compelling story. Out of the gate, the plots’s a dud. The only chance you have of keeping readers invested is if the character is one of those “can’t look away from” characters. And today’s character is that.

Our narrator for this story is RZA, one of the members of The Wu-Tang Clan. RZA is coming to meet Martin in prison. But, before we can learn what he needs from Martin, he tells us all about Martin’s story.

We meet Martin Shkreli as a 12 year old kid whose Albanian father is a janitor. Martin is embarrassed by his father’s job. But he’s even more embarrassed by the fact that his father has no desire to improve his life. In Martin’s eyes, that’s the ultimate sin.

Martin wants to be rich so, straight out of high school, he cons his way into an interview with Jim Cramer – yes, the wacky financial host – back when he was running a billion dollar hedge fund. After convincing Cramer to hire him, Martin learns the value of “shorting,” which is when you invest money in the hopes of a company failing. This teaches Martin that there is heaps of money to be made by taking a morally irresponsible approach to investment.

Martin eventually quits Cramer’s fund and starts his own fund in his mid-20s. Naturally, it fails, so he starts another one, and that fails too. Despite losing tens of millions of dollars of his clients’ money, Martin identifies a market that nobody is capitalizing on: You can buy the rights to a pill then raise the price of that pill to whatever you want.

So that’s what Martin does. He buys a pill called Thiola and ups the price from 15 dollars to 350 dollars. It is of no consequence to Martin that the pill saves lives and that, by raising the price, many people will die. Journalists ask him if he cares about this and he literally says no, he does not. All he cares about is profit.

What Martin doesn’t plan for is for his story to go viral. It even hits the late night talk show circuit, with Stephen Colbert and Seth Myers going after him. Martin, who operates under the m.o. of any publicity is good publicity, eats the attention up, even doubling down on social media.

But it ends up getting so much publicity that the SEC starts looking into him. What they find is someone with such an atrocious moral compass that they’re positive he has skeletons in his closet. They turn out to be right, identifying numerous laws he’s broken in his decade in the financial industry. So they arrest him and send him off to prison, where Martin is residing until next year, when he will be released and surely begin another sketchy company.

The Villain is an inherently challenging script to write in that the hero is the worst human being ever. Ferguson seems to know this and attacks it immediately. Martin’s father is a poor immigrant. Martin has no friends. Nobody gives Martin a chance. Martin gets accepted into multiple Ivy League schools but can’t go because he can’t afford it.

I think Ferguson realized that this guy was going to do such despicable things later on that he had to drum up as much sympathy for him as possible. Keep us around long enough to where we realize how weird and interesting this guy is. And then, by that point, even though he’s become a grade-A dickoholic, we’re so fascinated by the guy that we have to keep reading.

The script is also good by general biopic terms. I grade on a negative curve when it comes to biopics since I hate them but this is definitely one of the better ones I’ve read. I loved the choice of using RZA as a narrator. You’re always looking for ways to contrast and clash elements in a screenplay. That’s where you create excitement – combining things that don’t typically combine.

RZA’s streetwise no-B.S. narration (“But we first gotta run it back to the beginning. ‘Cause in the beginning was the word. I’m talking about the one place every rags to riches story in America begins — motherfuckin’ Brooklyn!”) was the perfect accomplice for a story about white collar Wall Street.

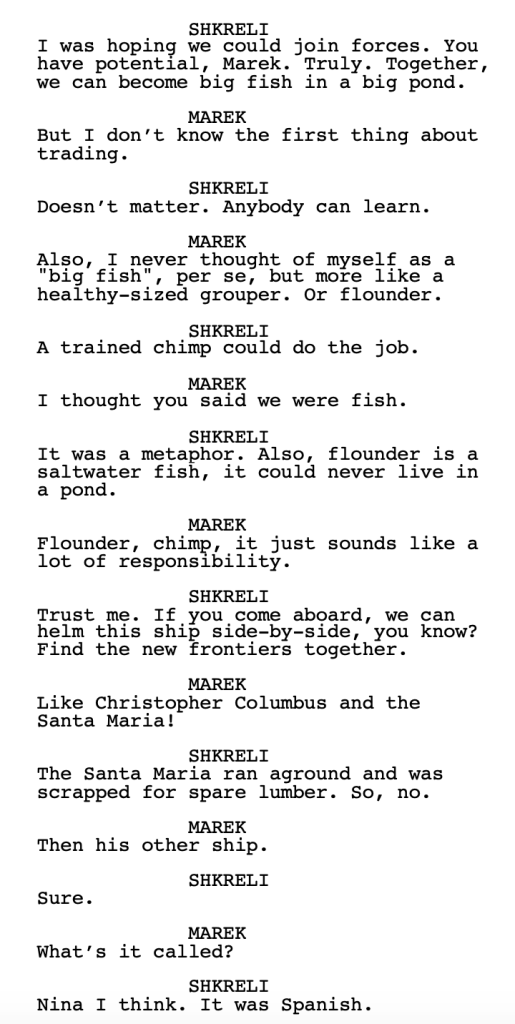

The dialogue is also good. It’s not quite Sorkin. But you get gems like this one where Cramer responds to Martin’s handshake (“Jesus, kid. You got the handshake of a teenage girl with polio.”) as well the below exchange, which I chuckled at.

But I think that the main reason the script works is that it gets your emotions going. That’s all you’re really trying to do with a script – connect with the audience on an emotional level. If you don’t achieve that, the audience will forget your movie within a week. If you do achieve it, they’ll remember your movie for a lifetime. Those are the stakes you’re playing with when it comes to emotional connection.

You can do this through love, like Titanic. You can do it through fear, like The Exorcist. You can do it through sadness, like Million Dollar Baby. Or you can do it through anger. And while anger is the least effective version of creating an emotional connection (since it’s a negative emotion) it still works.

We get so enraged when Martin price-gouges these people who will die if they can’t afford his pill that we’re now emotionally invested in the story. We want a resolution. We need to find out that someone’s going to come in and save these people from this insane man.

On top of that, there was something refreshing about a character who has zero interest in redeeming himself. Martin not only accepts his villain label, he goes out of his way to flaunt it. This guy is the embodiment of evil and I think that’s why the internet became so fascinated by him. Most people back down when they’re called out. He doubled-down. So we were kind of thrown into uncharted waters. If this guy has no desire to change, where does the story go? I wanted to know.

The one issue I had with the script was that it was a bit try-hard. It wants to be the next Social Network. It wants to be the next Wolf of Wall Street or The Big Short. But you can feel the writer pushing for that cool-factor (“Shkreli inhales breadsticks as he sits opposite Adele and SEC Officer inside the tourist-infested Olive Garden, surrounded at every turn by MAMMOTH MIDWESTERN MOUTHBREATHERS with their OVOID OFFSPRING devouring discount Italian by the dinnerplate”) and I’m not a fan of when I can feel the author’s presence. I want to be lost in the story. I don’t want the writer to remind me that he’s there.

With that said, this was pretty good. Definitely worth checking out if you’re also a biopic writer.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When it comes to narrators, writers tend to use the most obvious choice. Instead, consider the least obvious choice, like RZA here. I guarantee it will be more interesting.