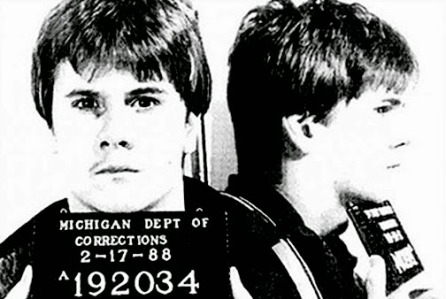

Genre: Biopic

Premise: At age14, Richard Wersche Jr. became an informant for the FBI. He spent the next two years helping take down the biggest drug gang in Detroit, Michigan.

About: There are THREE “White Boy Rick” projects in development, although this one, by most accounts, is the best of the bunch (so far). What’s interesting here (and a reminder for writers who like biopics but are afraid of copyright issues) is that writer-bros Logan and Noah Miller sold this as a spec. They didn’t have any rights to Wersche’s story. To be clear on that, nobody requires you to get the rights to a life in order to write a script about them. You can write the best biopic you can, and leave the “rights” issues to the production company and/or studio that buys the script. Logan and Noah Miller are probably best known for their 2013 indie film, Sweetwater, a Western that starred Ed Harris and January Jones.

Writers: Logan & Noah Miller

Details: 136 pages (undated – but the script went out in February of this year)

When not one, not two, but three production companies are all racing to make a movie about the same person, you figure that person’s life has to be pretty extraordinary. For that reason, I went into this screenplay with some high expectations. And you know what they say about high expectations?

It’s 1986 and 14 year-old Richard Wersche Jr. has the geographic lack of fortune to be born in one of the worst cities in America – Detroit. Detroit used to be the chest-puffed-out capital of the automobile industry. That is until the Japanese started making cars that were cheaper and better.

When that industry broke down, Detroit became a haven for gangs and drugs. But where there is chaos, there is opportunity. And Richard Wersche’s father got the idea to start selling guns to gangs. It’s not exactly legal, but it keeps food on the table. And who’s dad’s best employee? Wouldn’t you know it. It’s his son, little White Boy Rick.

One day Dad gets a knock on the door from the FBI. They know that if there’s anybody who’s got a beat on these gangs, it’s the man selling them guns. So they offer money to dad if he can give them the inside scoop. However, to their surprise, it isn’t Dad who knows everything about every customer, it’s his son, 14 year-old Rick.

As soon as the Feds realize that Rick’s a mini-Einstein, they employ him to infiltrate the drug community. This leads to Rick meeting the Curry Brothers, the number one dealers in the city, and three of the most dangerous motherfuckers you’ll ever cross paths with. The Curry Brothers like Rick. He’s an anomaly. A little white teenage brat who thinks he knows it all. That’s enough to embrace him and make him a key piece of the enterprise.

The movie then follows this little 14, then 15, then 16 year old kid as he’s pulled back and forth between the government and this gang, both of them taking advantage of and exploiting Rick. But Rick figures out a way to rise above it all. And when the Curry Brothers finally get caught with their hands in the crack jar, Rick’s there to take their place, becoming the biggest dealer in the city.

But then there’s no one left for the Feds to take down except for, ironically, the boy who got them there. So Rick is thrown into prison for the rest of his life, and not a single one of those Feds who used a minor to do their jobs ever got punished for it. Rick is still behind bars today, waiting for justice to be served to the men who took advantage of him.

I don’t know if White Boy Rick is a great script so much as it is a great real-life story. And this is what I keep telling you guys is the dirty little secret of screenwriting. If you find that awesome idea or that awesome character, the script will write itself.

I mean we have a 15 year-old taking down some of the biggest drug dealers in the country. He becomes a millionaire, making more money a month than, as he points out, the president of the United States. He ends up running the biggest cocaine trading pipeline between Miami and the Midwest. He’s used by both sides of the system. He USES both sides of the system. It’s no secret why three separate companies are rushing to turn this man’s story into a movie.

White Boy Rick also taught me that utilizing an “impending sense of doom” shouldn’t be limited to horror films. Here, the impending sense of doom is the main story element driving us to keep reading. We know that Rick can’t walk this line forever. Either the bad guys are going to figure out he’s playing them or the good guys are going to stop needing him, and when either of those things happen, he’s toast.

To that end, this script did a great job. I wanted to see how Rick would fall.

If the script has faults, though, it’s its unabashed desperation to land Scorsese as a director. Because Scorsese has made this film so many times now, what was once a unique product has become pure formula. Not unlike the “boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back” formula that drives a rom-com, the Scorsese Tragedy has its own familiar beats. And while Rick was an amazing character, you couldn’t help thinking of Goodfellas, or The Wolf of Wall Street, or Casino, when you read White Boy Rick. It almost feels like one of those scripts was chosen and these new words were simply pasted on top of the old ones, starting with the obligatory first act of pure main character voice over.

It’s a writing crutch we all fall back on. When we write a movie, the first thing we do is go back and watch all the similar movies to see what they did right. The problem with this approach is that, whether you’re aware of it or not, those story beats are seeping into your soul, and without you even realizing it, you’re soon copying those beats into your script. So sure, you may be doing what made that other movie work, but you’re doing so at the expense of originality. You need to deviate from the script sometimes, pun-intended.

Despite the familiarity of the formula, I’d still recommend this script because the title character is so freaking fascinating. You can’t believe this really happened. And the Millers did an excellent job of making Rick likable. This guy did some horrible things. He ran a drug organization that indirectly killed hundreds (maybe thousands) of people. Yet the Millers cleverly present Rick as the victim, the teenage boy who was taken advantage of by everyone in his life, even his own father.

And maybe that’s the lesson to take away from this. When you have an idea this good or a character this good, you can make a lot of mistakes in your script and the script still works. If you have a flimsy or light premise like, to use a random example, Enough Said (that rom-com with James Gandolfini and Julia Luis-Dreyfus), the tiniest mistake (a boring twist) could derail the entire story. White Boy Rick proves what happens when you have the ultimate subject. Much like Rick in real life, the script becomes bulletproof.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A common mistake I see in monologue-writing is the writer getting too wrapped up in what the character is trying to say, and then delivering an overly-rewritten on-the-nose monologue that’s boring as hell. Monologues are always more memorable when they’re unique, or, like a good story, deviate from the expected path. To that end, I loved this monologue in White Boy Rick. In it, one of the FBI agents asks Rick if he knows who Nancy Reagan is. Keep in mind that the point of the monologue is to convey how important it is (to both Rick and us) that the government win the war on drugs. Most writers would’ve written a very straight-forward dull message about how the war on drugs is destroying America and if they don’t do something soon, the fabric of the country will be permanently destroyed. Here’s how the Millers write it instead. AGENT TURNER: “Well, it turns out that the First Lady is very fucking angry these days. She’s so fucking angry that she’s declared war. A War on Drugs. You know what that really means? That means that if she doesn’t get what she wants, if she doesn’t win this fucking goddamn war, the President doesn’t get any pussy. She locks his dick out of her vagina. And that’s bad for the country. Hell, it’s bad for the whole fucking world. Because when the President of the United States of America ain’t getting laid, he gets really fucking frustrated, and the next thing you know the nukes start flying and we’re buried in World War III with the fucking Russians.”

Genre: Noir/Superhero

Premise: A unique interpretation of the Superman vs. Batman story that reinvents the characters and cleverly avoids outright association with either property.

About: Screenwriter Jeremy Slater has the dubious honor of having his name attached to the biggest bust of the year, Fantastic Four. But there were some extenuating circumstances. First of all, whatever movie Slater wrote clearly isn’t the one that showed up at theaters this weekend, as the film has been famously repurposing itself over the last six months. And second, just being asked to adapt a major franchise is a HUGE EFFING DEAL as a screenwriter. It’s the equivalent of what used to be the big spec sale. It means you’ve arrived. And Slater got this job by writing the screenplay I’m reviewing today – a screenplay that many consider to be one of the best in Hollywood.

Writer: Jeremy Slater

Details: 2012 draft

Man of Tomorrow has been slip-sliding around in my read pile for the better part of 3 years. At some point, I just forgot what it was about and it slipped into read purgatory. Then the script came up in a few recent conversations and people were like, “You haven’t read Man of Tomorrow??”

The record scratched. Everyone in the room turned. My script ignorance was put on blast – not something I’m used to. I know the script was on the Black List a few years ago but wasn’t it somewhere near the bottom? That was all part of the mystique that surrounded Man of Tomorrow – mystique that would play into this dark and unpredictable read.

The year is 1946. 50-something Paul Harrigan is an FBI agent who’s been tasked with the impossible – containing Tommy Anders, the man who has taken over Chicago and turned it into a spot so crime-infested that even Al Capone would be disgusted with it. And Al Capone actually makes an appearance in this movie so a reaction like that is possible!

The reason Tommy can just take over a city is because he possesses super-human powers. He’s stronger than a thousand men. Bullets bounce off his body. And rumor has it he can even fly. But unlike his doppelganger, the superhero who shall not be named (his name rhymes with buperban), Tommy uses his powers for naughty reasons, namely running the biggest criminal organization in the country.

Tommy’s only problem is that a not-so-nice man named Erinyes doesn’t like him. Erinyes is a psycho with a gravelly voice and a silver mask who keeps killing Tommy’s men. His message is a simple one: “Get the hell out of Chicago or Ima gonna make you dead.” My words not his.

While Tommy doesn’t want to admit it, Erinyes is the first mortal he’s ever been afraid of. More specifically, he’s scared Erinyes will kill the love of his life, Lili. You can’t stop bullets if you’re not around when they’re fired.

What follows is a story surprisingly full of twists and turns that plays out under a Pulp-Fictionalized timeline, one that jumps back and forth to tell its story out of order, as if the script hadn’t catered to the geek populace enough. When it’s all said a done, Hitler, Al Capone, a nuclear bomb, and lots of heavy shadows will make cameos in “Man of Tomorrow,” a non-traditional script if there ever was one.

So there’s this growing contingent of people out there saying that since the spec script is dead, there’s no reason to try and write a script to sell anymore. It makes more sense to determine what kind of movies you want to write in Hollywood, then write a really weird out-of-the-box story that exists adjacent to that universe.

So if Jeremy Slater wants to write a Superman movie, it doesn’t make sense to write a movie about a superhero who saves the day. That’s every superhero movie ever. Instead, set your story in the 1940s. Create a Superman vs. Batman storyline, but rename the characters and modify their powers a bit. Throw in a film noir style and jump around in time to really shake the story up.

Now you’re got something that shows you can write a superhero movie, but you’ve also proven that you have a unique voice and that you think outside of the box.

To this strategy I say… hold your horses. I still think you can sell scripts if you target genres that are still selling (Thrillers, Horror, Comedy) and you execute them well. I also think there’s a fine line here. Man of Tomorrow shows what happens when a writer executes this strategy successfully. But I read the 100 other scripts that execute this strategy miserably.

Cause the thing is, just being different isn’t enough. You still have to know how to tell a story. And I can tell that before Slater wrote this screenplay, he wrote plenty of traditional scripts. It takes control to be able to jump back and forth in time and not lose the reader. It takes skill to create characters with as much depth as these (Harrigan is drowning in internal conflict, and both Tommy and Erinyes have extensive and heartbreaking backstories).

The point is, yes, writing something outside of the box is good, but you still need a solid understanding of storytelling to pull it off.

This leads us to the more pertinent question of is today’s script any good on its own (regardless of its weird approach)? I’d say yes, but I didn’t like it as much as everybody else seemed to. And everybody else REALLY seemed to like Man of Tomorrow (writers have literally said to me: “You haven’t read Man of Tomorrow?? Cancel the rest of your day and read it now!” “But I have a doctor’s appoint—“ “CANCEL IT NOWWW!!!!”)

I think it’s because I’m not a film noir guy. I don’t like stylized reality (I’d rather have my skin peeled from my body via a potato peeler than watch a movie like Sin City). I like things to be as grounded as possible (unless the genre dictates the opposite, like Star Wars). And I detest alternate history. In this script, Tommy kills Hitler and wins World War 2. Erinyes is the creator of the atom bomb, which he plans to use to kill Tommy. It was all a bit too geeky for me.

But there’s no question, when you read “Man of Tomorrow,” how much skill is on the page. Here’s a random sample of the writing I copied from page 3: “The old guy still has a flair for the dramatic. He pauses to light a cheap cigar, takes a few puffs, exhales greasy smoke through his teeth. Never taking his eyes off Tommy.” That level of detail is far superior to what I usually read, which is something closer to this: “Our hero is smoking as he stares at the other man. He looks him hard in the eyes. There’s a clear dislike between the two here.”

So if I had a higher Geek degree, I’d probably be giving this five stars. But from where I stand, I’ll have to appreciate it more from afar. Which is still pretty impressive when you consider I’m generally not a fan of this stuff.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The right action, no matter how tiny, can sell an entire character, which can be critical early on in when you need to convey newly introduced characters quickly. Let’s look at the very first action of our hero, Harrigan: “We find HARRIGAN shoveling a porterhouse steak into his mouth.” Reread that and pay close attention to the details. The verb “shoveling” indicates aggressiveness. And a “porterhouse steak” is a very masculine food. 10 words! 10 words is all we needed to give us a sense of this character. To bolster this point, consider how differently you imagine Harrigan when I introduce him this way: “We find Harrigan nibbling on a cucumber roll.” You’re imagining a completely different character, right? That’s how important actions (even tiny ones, like how they eat) are in selling your characters.

Much ado has been made about the disaster that is Fantastic Four (25 million opening weekend on a film that, when conceived, the studio hoped would make 70-80 million). The film has been getting roasted for months in LA, with whispers (actually, let’s be honest, screams) of how the entire production fell apart due to young untested director Josh Trank going AWOL (Word is he would lock himself in his trailer for days, doing blow instead of directing).

People have been saying that they were still shooting scenes as recently as a month and a half ago. That’s unheard of for an industry that spends the large majority of its time in post-production. Star Wars, for example, will have stopped shooting for a year by the time it comes out in December.

Then Trank had the cojones to come out on Twitter and call the movie terrible, claiming if Fox would’ve just let him make the film he wanted to make, they would’ve had a good movie on their hands. Yikes. You’ve already pissed off the monster. Why are you walking back into his den and taunting him? It’s a move that if you’re choosing sides on who’s to blame, Trank tipped the scales in his favor. How do you not have enough self-awareness to know that everyone in town is already skeptical of you? To publicly trash the hand that feeds you the night before your movie opens? It doesn’t matter if you’re right. You need to know when to lay low and ride it out.

All this noise, however, has masked the bigger question. Should Fantastic Four have been made in the first place? As a screenwriter, one of your jobs is to gauge whether your idea is actually a movie. One of the biggest mistakes I see by far from amateur writers (although it happens plenty in the professional ranks too), is committing to an idea that isn’t a movie.

Now of course, this is a subjective question. What one person deems a worthy idea, another deems the worst idea ever. But there are definitely elements – from genre to conflict to irony to uniqueness to subject matter – that factor into whether something is worthy of being a movie.

Take a movie like “Shame,” which starred Michael Fassbender and was directd by Steve McQueen. Is that a movie idea? It’s a vague exploration of a man with an addiction who lives with his sister. Sure, the movie looks amazing because it was directed by McQueen. And the performances were good because the actors were good. But if you stripped those things away and just looked at it on the page, was it a movie idea? No, it wasn’t. It was two characters in search of a story.

When I look at Fantastic Four, I wonder if it’s a movie idea. Its main superhero’s power is that he can stretch. Another member of the group turns into a rock man. How did they get these powers? Errr, cause they went up in space and, uhhh, something caused a change in their molecular structure?

I know we just got done celebrating a movie called Ant-Man, but at least Ant-Man was unique. At least it allowed the filmmakers to explore things that we hadn’t seen before in the superhero universe (the battles that take place when you’re the size of an ant). Here we just have some superhero powers that don’t make a lot of sense and aren’t that cool in the first place.

The biggest superhero films so far – Spider-Man, Iron Man, Batman, Superman. Their powers are simple and very easy to understand. We don’t understand Fantastic Four, and hence we’ve never embraced it on the big screen (this is the third incarnation in which it’s failed).

I guess what I’m saying is, you have to try and recognize when your idea doesn’t work. Especially as a spec writer where you’re going to be spending at least a year on something if you’re going to make it good. If you’re sensing problems in the idea before you even write the first scene (How do I make a character with stretchy-powers cool)? I GUARANTEE those problems aren’t going to magically go away on Month 7. Sure, you can take a chance. And sometimes we do figure the issues out. But more often than not, the obstacles are insurmountable, and that, I believe, is what happened to Fantastic Four. It was never a movie in the first place.

Moving from movie superheroes to writing superheroes, Diablo Cody just came out with a new movie this weekend. It’s called Ricki and the Flash and stars perennial Oscar winning actress Meryl Streep as an aging rocker who’s always put music in front of her family.

The movie went out wide (to about 1600 screens. For reference, FF4 had 4000 screens), and finished with a paltry 7 million bucks. So here’s my question – and it’s directed specifically at female viewers. Tons of noise has been made over the past few years about the lack of equality in the entertainment business.

Men get all the writing jobs, the directing jobs, the acting jobs. And women believe they’re not being represented. Ricki and the Flash is clearly a response to that criticism. It’s got maybe the best actress in history in the film. It was written by the most recognizable female writer in the business. And it’s a female-themed movie on almost every level.

So then why didn’t women show up to this? Why aren’t they supporting what they say the market is missing? Is the answer simply, bringing back the earlier topic, it’s a bad idea? And if this is not the kind of movie women want made, what is the kind of female-driven movie project that women want made? What is the market missing?

I want to finish today by addressing a question I saw in the comments of one of last week’s posts. I had talked, in the post, about how the characters in the script I was reviewing needed to have more depth. And a commenter replied, “Well, yeah, but what does that MEAN??” Everyone in the industry SAYS that, but then they don’t say how you actually create characters with depth.

Well, I’ll come to the defense of these people by saying that explaining how to create depth in your characters is going to take in the neighborhood of 4000 words AT LEAST. It’s not something you can just bust out in a sentence or two.

Still, I wanted to answer this question for that writer. And recently, I’ve been getting into cinematography. It turns out lighting presents the perfect analogy for character building. The first thing a cinematographer does when he’s lighting a scene is he figures out the main source of light. Maybe it’s a window. Maybe it’s a lamp. Maybe it’s a laptop screen. Once he’s located that lighting source, that’s his in-point to lighting the scene. He puts a main light up to mimic the source of that light, and then he evolves the lighting from there, adding more lights to fill up the scene where he needs to.

When you create a character, you should be thinking in a similar manner. You need that base source of light. And, to me, that’s the character’s flaw. Or, more specifically: “What is the one thing that has been holding this character back from becoming a whole/happy person?” It might be that they don’t believe in themselves. It might be that they’re selfish. It might be that they’re stubborn. In Ricki and the Flash’s case, it might be that they’ve put their work in front of their family their whole life. Whatever the case, that is your main source of light for creating depth in a character.

Of course, just like a cinematographer will then start filling in the location with more lights (a “rim” light, a “fill light,” practical lights), you can fill your character in with more traits that create depth. For example, maybe your character has a vice (drugs). Maybe they have issues with their father. How many “lights” you add is up to you. But as long as you have that first one – that main source of light – you’ll have created a character with some level of depth. Hope that helps.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise (from writer): Two young brothers search for buried treasure with hopes of helping their struggling family, but when they uncover an otherworldly artifact with mysterious properties, they find it may have far greater value than they imagined.

Why You Should Read (from writer): This is my sixth screenplay and I’m still realizing, “Man this writing stuff is still hard!” Several months ago, I received two rounds of notes from Carson and after each round, I sucked it up and made the necessary cuts and addressed the dreaded “more character development” notes. Now I hope to get another round from the SS faithful. Carson described this as Stand By Me meets E.T. I thought that was a great comparison, and basically what I was aiming for. No big explosions. No black ops military assaults. No zombies driving fast cars. Just kids on an adventure. Period. Hope you enjoy it. And it chosen, I will definitely be around and interacting in the feedback if I’m lucky enough to have anyone read it.

Writer: Joe Voisin

Details: 109

As Joe notes in his WYSR, I’ve already read this script TWICE, so I was curious to see what new tasty treats Joe would be bringing to the third draft.

And I think Joe brings up a good point. Even when you’re on your sixth script, which a lot of writers never get to, it’s STILL HARD. In many ways, the more you learn about screenwriting, the harder it becomes.

You can master one area (say, plot), and still be at the bottom level of character, or dialogue, or pacing, or structure, or concept. The key is identifying where you need to get better and then practicing.

Sometimes I recommend using short scripts to get practice in. So say your scripts lack suspense. Write a few short scripts where you focus specifically on creating suspense. If you don’t practice these things, you’re never going to get good at them.

Unearthed introduces us to scrawny 10 year-old super-smart, Jonah. Jonah is out treasure hunting with his 14 year-old brother Henry, a young man who’s ready to take the next step in life. The two are barreling through farmland and forest with their family’s metal detector.

Surprise surprise, they find a buried sword. But not just any sword, a sword from the Revolutionary War! This is important, as the family is dirt-poor at the moment, their mother, Lara, struggling to make ends meet on a factory salary.

With their grandfather, Matthias, in need of expensive medication to ward off bouts of dementia, the money this sword might bring could really help them out.

But before the boys take that step, they realize there’s a lot more where that sword came from. When the metal detector starts beeping off the charts, further digging shows that there’s a giant structure under the earth. But what the hell could it be?

Meanwhile, evil neighbor Cyrus, an old bastard with nothing better to do than be an asshole, catches on that something’s happening on his property, and he makes a move to shut the boys down. But as the brothers unearth (literally) more clues as to what this underground object is, it becomes clear that their town has been harboring an incredible secret for the past 300 years.

I’m not surprised that Unearthed won the Amateur Offerings week at all. The script is a super easy read. Joe keeps his sentences simple and easy to digest and I wish more writers would take that approach to heart.

Sometimes writers think they have to impress you with their vocabulary and their wordsmithing skillz and as a result we get zig-zagged through the most perilous of sentences, usually with no idea what the writer was trying to say.

None of that here.

And there’s a sense of wonder and boyhood curiosity that makes you feel all warm and fuzzy when you read Unearthed. You really like Jonah and Henry and you want them to succeed.

My issue with Unearthed has always been two-fold. I don’t know if it’s a big enough idea. And I don’t know if enough plot has been packed into the story.

Let’s start with the first issue. Whenever you tackle the sci-fi genre, the expectations are high. The audience wants to be taken to a world they’ve never seen before, even if you’re exploring things on a low-budget level. I’m not sure that happened here.

Unearthed is frustrating in that I always kept waiting for something big to occur, but it never did. I felt like the foreplay kept going on forever. We find a sword, we find a structure underground, we find a probe thing. I wanted that big plot point to arrive and turn this into a bigger-feeling movie.

To use E.T. as an example, we go big right away. There’s an alien living with a boy. We’ve already been taken to that “next level” from the get-go. But I suppose an example of that script elevating itself to the next level would be the government moving in. It took what was essentially a small character-driven movie and made it into something that felt bigger.

That moment never came here. It always felt like four people taking a really long time to discover something that was only kinda cool.

And that leads me to the second issue – I want Joe to learn to push through his plot quicker. For example, the first two scenes have Jonah and Henry finding a sword in the forest and then rushing downtown to pick up their grandfather, who’s wandered out because of his dementia.

Now let me ask you, how many pages do you think these two scenes should total? Take a second and map them out in your head. What’s the page count?

Well, it takes Unearthed TWENTY pages to get to that point. That’s nearly 20% of the entire screenplay. 1/5 of your story has been spent on finding a sword and getting Grandpa in town.

As writers, when we’re in the moment, it always feels like we need more time than we actually do. We want to play out those beats and those exchanges way longer than they need to be played out. And we don’t realize just how long those beats feel to the reader.

I’d say, at most, you’d need 8 pages for those two scenes. And I’d encourage Joe to actually go shorter than that. And the side benefit of doing this? You now have more time to add MORE PLOT to your story.

And that’s what Unearthed needs. It needs more going on.

Now I suppose there’s a counter-argument to this. Stand by Me didn’t have a whole lot going on plot-wise. The stakes were fairly low (going to look at a dead body). So what gives?

Well, a couple of things. Stand by Me wasn’t sci-fi. So again, there’s an expectation that when you bring sci-fi into the mix, the audience wants more. They want bigger. And second, while Stand by Me didn’t have a whole lot of plot, it had some of the best character work and character interaction ever put on screen.

And that’s important for writers to remember. I always say that the game is changed when a movie does something better than any movie that’s ever been made. There’s no plot in When Harry Met Sally, but that movie has the best dialogue ever put in a romantic comedy EVER. So it can get away with plot issues. Ditto, Stand by Me. The characters in that movie were just so vibrant and deep, it overcame the fact that there wasn’t a whole lot going on plot-wise.

And I suppose that brings me to the final issue with Unearthed. The character work. I will say this. Joe has improved the character work A LOT here. I remember in the first draft there was nothing going on between the brothers.

At least now we have some issues in play. Henry is growing up. He wants to go do his own thing. And that means Jonah is dealing with the possibility of losing his brother.

I just think Joe could’ve pushed this more. Like A LOT MORE. To be honest, I like the idea of Henry running off to live with his father more than him refusing to move with his family to Savannah. There’s more depth to the decision to chase after a father who’s shown he doesn’t care about you.

So if Henry is telling Jonah, in confidence, that he’s going to run away in a few days to go live with their dad, and telling Jonah he can either come with him or stay here in this shit town, the stakes in this relationship are going to be a lot higher and you’re going to find a lot more conflict in their dynamic.

I really want to give this a “worth the read” because of how much the script has improved. But I still think the small story, the slow-moving plot, and lack of truly strong character development is holding Unearthed back.

But watch out for Joe. I’m sure he’ll only continue to improve.

Script link: Unearthed

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Screenplay real estate is SUPER VALUABLE. Realize that a 10-page scene is taking up 1/10 of your entire movie. So if you’re going to write a scene that lasts that long, it needs to be an amazing fucking scene or super-duper important. Otherwise, shorten it. A lot.

It’s not easy facing the truth. But the truth is what the truth is. The spec market is in the toilet right now. How did this happen? Well, that’s complicated. But for the most part, if you want to know how we got here, look in the mirror. That’s right. The reason we’re in this predicament is you. You haven’t been writing good enough screenplays. It’s not like all the studio heads got together one day and conspired to eliminate spec sales. The specs that have become movies, outside of a few exceptions, have performed badly. And I’ve pinpointed 10 of the worst offenders – the dastardly group that’s gotten us into this mess. Afterwards we’ll try and learn from these mistakes and possibly forge a new path. But for now, we must accept our reality.

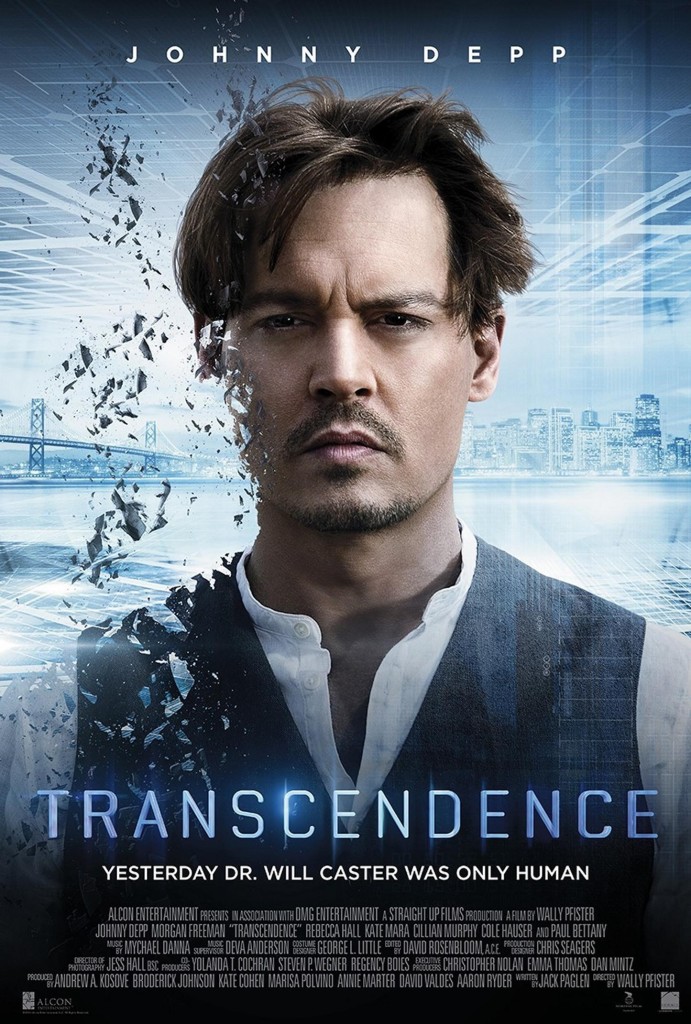

1) TRANSCENDENCE – Transcendence seemed like a solid bet at the time. It was a cool thinking man’s sci-fi script, and after the success of Inception, it was assumed that Hollywood wanted more of this. It even starred one of the biggest actors in the world, Johnny Depp! However, what the writer and filmmakers failed to see (as did I – I gave this script a good review), was just how still the story was. From camping the entire story out in the desert to the main character being locked inside a 70 inch screen, there wasn’t any action for a movie that set itself up to be action-like. As I’ve said before, movies work best when they MOVE. Transcendence sat its big ass down in the middle of the New Mexico desert and stayed put for 120 minutes. And that turned out to be 120 minutes of hell.

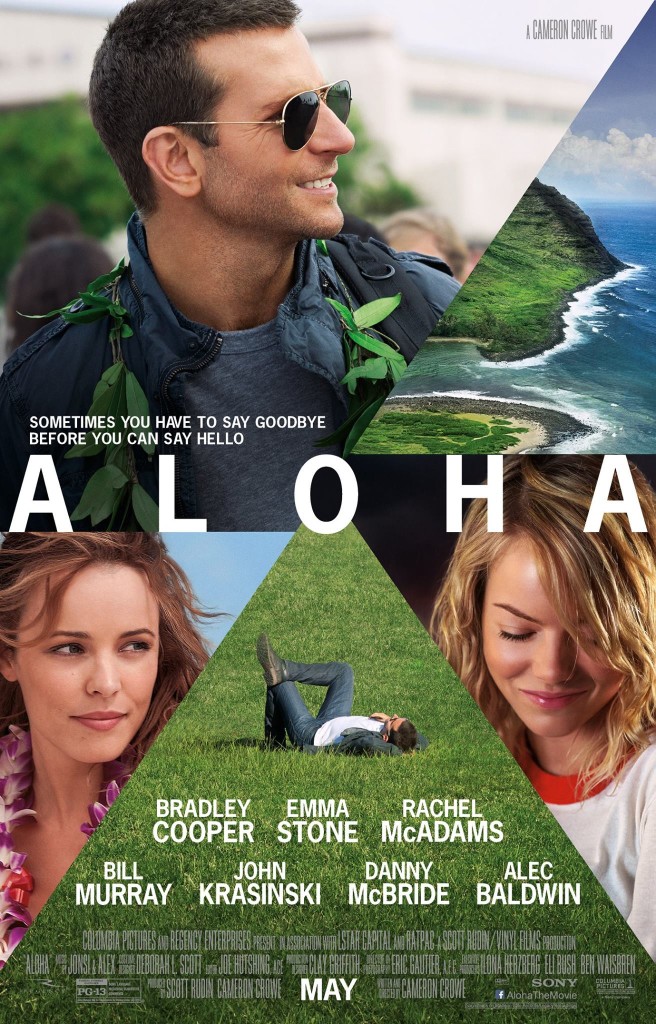

2) ALOHA – If you want to know why studios are so scared of original material, look no further than “Aloha.” Let me tell you who starred in this movie. BRADLEY COOPER and EMMA STONE! Two of the biggest movie stars IN THE WORLD. And the movie still bombed. Aloha supposedly offered moviegoers what they said they wanted more of – something different. This was an offbeat military romance set in Hawaii. You can’t get any more different than that! The problem was Crowe took “different” too far. This movie clearly didn’t know what it wanted to be. It contained way too many elements (Hawaii, volcanoes, satellites, music, romance, comedy) and eventually got lost in them. You don’t need to see a movie to know when the vision isn’t unified, when the story isn’t clear. All you need to see is the trailer. And nobody knew what the hell Aloha was about after they watched this trailer. So they didn’t show up.

3) THE GUILT TRIP/DANNY COLLINS – I actually thought both of these scripts were fun. But here’s the thing with them. Dan Fogelman was ON FIRE between 2010 and 2011. The guy was the one writer consistently selling scripts for 7 figures. And when that kind of stuff happens, it’s contagious. It makes other studios want to put up big money for high profile specs as well. Therefore, when neither of these films did well at the box office (30 million and 5 million respectively), they were higher-profile failures in the screenwriting world. If each script sold for low-six figures, nobody would’ve cared. But with the scripts costing so much, it’s a direct indictment on high-spending for screenplays. Hence, buyers will be less inclined to take big chances like this in the future.

4) WHITE HOUSE DOWN – White House Down wasn’t just one of the biggest spec sales of the year. It was one of the biggest spec sales EVER. 3 million bucks. And to that end, this may have been the script to bring the casino down. Once a screenplay with that much money behind it bombs, it’s hard to make a case for spending a lot of money on a spec. Now I thought they completely botched the packaging for this movie. They went with the typical hot actor (Channing Tatum) mixed with a total wild-card (Jaime Foxx) and threw in the poor man’s Michael Bay to direct. You can’t just throw random “hot” elements at a project and call it a day. That’s Hollywood packaging. Instead, you need to find a group of elements that work together – that have chemistry. Let’s remember that Die Hard didn’t star Arnold Scwarzenegger. It starred, at the time, a relatively unknown TV actor who was perfect for the part. In the end, this movie screamed style over substance, and when the audience smells that, they stay far away.

5) VANTAGE POINT – For those who don’t remember Vantage point, it was a 2008 film about a bomb that goes off in a crowd and we make repeated jumps back in time to see it from different people’s perspectives (vantage points). The reason I included this script is because here we have this spec-friendly high-concept idea, something fun enough to get a wide release and a big marketing push, and the movie tapped out at 75 million dollars. That’s not bad. But I believe this movie, and others like it, have created this psychological belief that 75 million is the ceiling for a spec screenplay at the box office. Because this movie really did have all the elements to succeed. Good concept. Unique. Easy sell. And still it gets nowhere near IP box office numbers. Films like Source Code and The Grey haven’t helped. Those were both great scripts and solid movies. But audiences refused to give them more than 50 million dollars. This creates this belief in a lot of people working in the industry that spec script movies have a low ceiling. And that hurts us screenwriters.

6) DRAFT DAY – Draft Day was the number 1 script on the Black List and a memorable spec sale. It was yet another project catering to the idea that audiences were looking for something different. However, I have never seen both a lead actor and director on a movie look so bored. Kevin Costner mumbled his way through his entire performance. And the direction was so freaking dull, I wouldn’t be surprised if behind-the-scenes footage showed director Ivan Reitman asleep half the time. This movie needed to be directed with the kind of attitude and zest a young Cameron Crowe displayed (“SHOOOWWW MEEE THE MONNNNEY!”). Instead it was presented as a dull sports caper. But here’s the reality with Draft Day. And I say this as someone who loved the script. It was never a movie. Non-true-life sports movies are really hard to make money off of so unless the execution (acting and directing) are historically amazing (as they were with Jerry Maguire), scripts like this have no chance of doing well in the market. This really shouldn’t have been held against the screenplay market as this movie probably shouldn’t have been made in the first place.

7) SEX TAPE – Sex Tape was a huge 7-figure sale. Sony really went all in on this one. But the movie barely made 30 million. You have to wonder why the company thought such an ancient idea (the lost sex tape concept went back 20 years) would bring people to theaters. In addition to this, they did a horrible job casting. Like god-awful horrible. Jason Segel and Cameron Diaz? In what universe are these two a married couple? I’ve never seen two actors look more awkward together. Unfortunately, despite it being obvious to most everyone outside of Sony that this movie wouldn’t work, the fact that it bombed is still taken out on you, the spec screenplay writer. It’s considered proof that audiences don’t connect well with “original” ideas.

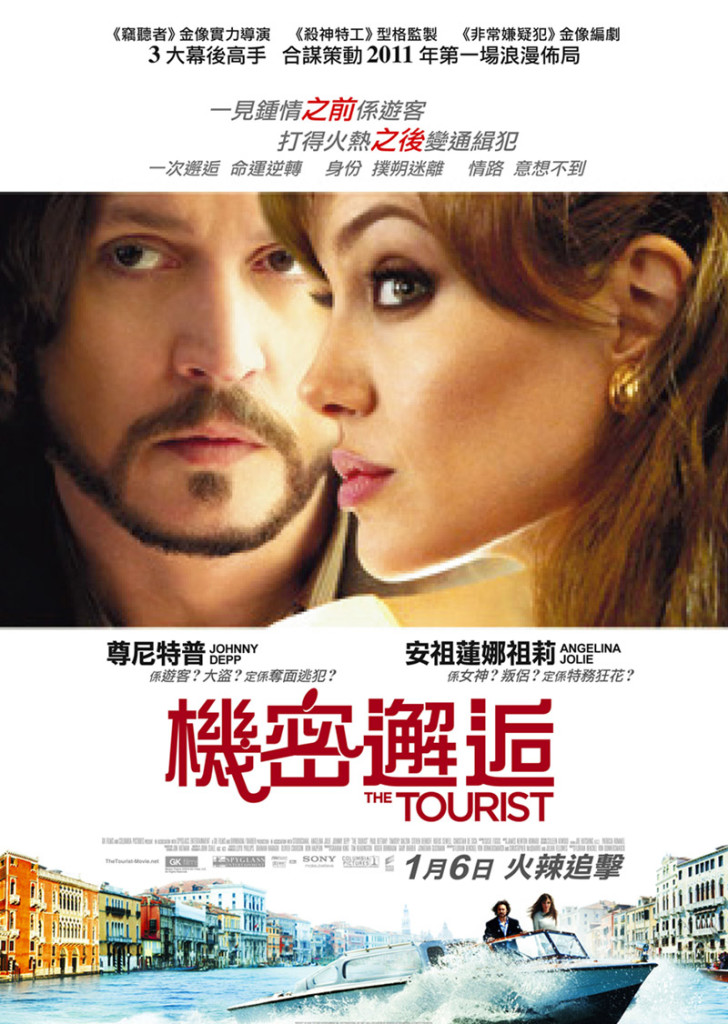

8) THE TOURIST – The Tourist was supposed to be this sexy mystery thriller and I actually thought the script was okay. But here’s where spec scripts get in trouble – when you throw huge movie stars at them and they don’t perform well. Because when a movie like The Tourist goes bad, nobody blames mega-stars Angelina Jolie and Johnny Depp for the failure. We’re talking about Hollywood royalty here. Instead, the onus is placed on the script. It must be the writer’s fault. And in some ways, they’re right. I remember the script relying way too much on its twist, a twist that, if you were reasonably intelligent, you saw coming a mile away. But it certainly didn’t help that the script was directed sleepily by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck. I seem to be the only person on the planet who thought his “The Lives of Others” was a snore-fest and so wasn’t surprised at all that this was a bore as well. But I think the lack of an identifiable genre was the nail in the coffin here. Was this a romance? A thriller? A mystery? In that sense, it suffered from the same fate as a similar spec-project, Tom Cruise’s Knight and Day. When you’re off in genre nowhere land, it’s hard for audiences to understand what they’re going to see. So they choose to see something else instead.

9) CHAPPIE/AFTER EARTH/ELYSIUM – Sony seems to be the root of a lot of the spec script disasters that have put us in this mess. And that’s unfortunate, because Sony was one of the only studios buying original material. Therefore, the failure of that material seems to broadcast a bigger message to the industry – “A studio that relies too much on original material fails.” After Earth wasn’t a terrible movie but it constantly felt like a big movie trying to break out of a small one. The vanity aspect of father and son working together didn’t help. Chappie was completely mis-constructed from the ground up. This was a kids movie (adorable robot main character) thrown into a hard-R scenario?? Who allowed that?? Eylsium was the best of these three films, but the screenplay was paper-thin and you could feel that all the way through. Even critical plot points like the transport method from earth to Elysium felt like they were thought up in five minutes. What kills me even more about the failure of these films is that they’re all sci-fi, and I love sci-fi.

10) 47 RONIN – I don’t know what happened between the time I read an early draft of this screenplay and the film being released, but someone got into this screenplay and fucked things up. I read a grounded story about disgraced warriors fighting in ancient Japan. Then someone decided to throw a bunch of monsters and dragons in it, I suppose to broaden its appeal. The thing is, you can’t throw dragons and monsters into something without a really well-established mythology. It’s the difference between movies like Lord of the Rings and The Seventh Son. You can feel how well thought-through the mythology is in Rings, where as with The Seventh Son, it looks like they’re throwing monsters on the screen cause audiences like monsters. Ditto 47 Ronin. It just looks sloppy and audiences can sense that, even in the previews, which is why no one showed up to this. And this one REALLY hurt us, guys. Like really really. Because I think this movie cost almost 200 million dollars. And when an original idea costs that much money and it bombs that badly, the entire ‘original ideas’ market is blamed.

So is there an overall theme to the mistakes made here? There seems to be three stages to that answer. One, some concepts (Sex Tape) just weren’t that good to begin with and should’ve never been made. Two, some concepts that were good had lazy execution (Vantage Point). And three, the few concepts that were both good and had solid execution were badly cast or directed (White House Down). As writers, we don’t have control over number 3. But we have control over 1 and 2. And that’s the message I’ve been throwing around here forever. Start with an exciting concept and then give the execution everything you’ve got. Don’t give us the sloppy Vantage Point draft where you only explore 50% of your concept and call it a day. Give us the best script you’re capable of writing at that point in your life.

Now a lot of you may be bummed after reading this article. It’s not easy hearing the truth. But the way I see it, understanding why your industry (the spec screenplay industry) isn’t working is the first step towards fixing it. And I think some good things are coming around the corner. Netflix is moving into the movie business FAST and if that works out, expect the reemergence of the mid-price (30-50 million) movie. That means a new potential spec market will be in play. And, again, all it takes is one big spec success for this copycat industry to get excited about the spec market again. Next week, we’re going to talk about some of those scripts, as I offer up 10 screenplays that could turn the spec market around. Seeya then!